Two Witnesses Testify on Purges of Cadres and Military Structure

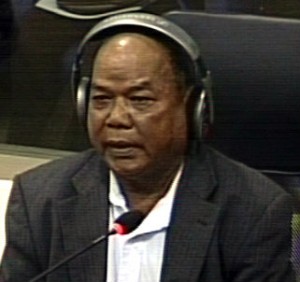

Witness Ong Ren testifies before the ECCC on Wednesday.

Former Khmer Rouge army regiment commander Ong Ren took the stand in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Thursday, January 9, 2013, providing an in-depth account on the structure, personalities, arrest, and purges of cadres at Division 801 in Ratanak Kiri province. His testimony included details of his own dramatic, narrowly-avoided arrest; Khmer Rouge military operations in and around Uddong during the time of that city’s fall; and the role of Son Sen in carrying out the evacuation of Phnom Penh.

Earlier in the day, the Chamber heard a second day of testimony from witness Sor Vi, a former Khmer Rouge messenger, soldier and guard at K-1, Pol Pot’s residence during the Democratic Kampuchea (DK) era. Under questioning from the Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary defense teams, Mr. Vi concluded his testimony by providing further insight into guarding arrangements at K-1 and describing the arrests of various cadres. Notably, the witness was also engaged in a discussion concerning the circumstances of his interview with the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (OCIJ) with the Khieu Samphan Defense Team, which suggested that there was a lack of clarity around whether the OCIJ had interviewed the witness once, as was officially recorded, or on more occasions.

Trial Chamber President Orders Ieng Sary and Nuon Chea to Participate from Their Holding Cells

Approximately 150 villagers from Kandal Stung district, Kandal province watched the proceedings from the public gallery this morning. Many appeared to have been born during or prior to the DK period. They witnessed Trial Chamber Greffier Se Kolvuthy open the day’s proceedings with an attendance report. She advised that all parties were present, but for International Co-Counsel for Ieng Sary Michael Karnavas, who was again absent due to personal reasons, although he would ultimately arrive later in the day.

Following this, Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn advised that Ieng Sary’s treating physician, Dr. Lim Sivutha, had examined the accused and reported that Mr. Sary was fatigued and unable to follow the proceedings from the courtroom. As such, the president instructed, as he also had on Tuesday, January 8, 2013, that Mr. Sary should instead follow the proceedings from his holding cell.[2] Similarly, the president continued, the accused Nuon Chea was fatigued, dizzy, exhausted, and unable to sit for long periods. Therefore, the Chamber would also instruct that Mr. Chea participate from his holding cell. President Nonn remarked that these decisions were taken in consideration of the need to avoid a substantial delay to the proceedings.

Khieu Samphan Defense Team Seeks Clarification from Witness on Various Matters

Former Khmer Rouge guard, soldier, and messenger Sor Vi then took the stand for his second day of testimony[3] under renewed questioning from International Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Arthur Vercken. Mr. Vercken first directed the witness back to his earlier testimony concerning an individual named Ta[4] Soth. Asked to describe Mr. Soth’s position, Mr. Vi said, “He was the deputy chief of K-1 Office until 1978, if I remember correctly.” However, by the time Pol Pot and other senior leaders fled to the west in 1979, Soth was no longer in his position, the witness added. At this point, there appeared to be some confusion as to whether Soth eventually replaced Tan as the head of K-1. The translation suggested Mr. Vi had said this, but when Mr. Vercken put this to him, the witness advised that this was incorrect.

Moving on, Mr. Vercken noted that in Ta Soth’s statement, he did not talk at all about having served at K-1 Office but instead headed troops at the Vietnamese border. He asked for Mr. Vi’s reaction to this statement. Mr. Vi duly stated that he could not “grasp” this. However, he continued, he saw Soth at K-1 Office in “mid-1978.” Soth also had another position, according to the witness: “He worked with Tan until 1979.” Clarifying the earlier confusion, Mr. Vi explained that “when Tan was not there, he would replace Tan in his capacity as chief.” However, “between 1975 and 1977, I did not know where [Soth] lived or what he did.” Mr. Vercken asked whether this meant that Soth was not, in fact, heading troops at the Vietnamese border in 1977. Mr. Vi reiterated his testimony that he saw Soth at K-1 in 1978.

Mr. Vercken noted that in Mr. Vi’s prior testimony to the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (OCIJ), he had said that he often associated Soth with Tan and another individual, Pang, and that he had learned from Soth and Tan that Pang had been arrested and accused of treason. He asked whether Mr. Vi could confirm this. The witness agreed that this event indeed occurred “a few months” after Pang’s arrest, although this was not at an “official meeting.”

According to the written record of Ta Soth’s interview with the OCIJ, Mr. Vercken related, he said that “one day, Pang’s driver told me that Pang had died, that he had been killed by bandits, shot down when he went to pick up supplies, such as … Korean boats in Kampong Som harbor” and was killed at a location near Sre Ambel.[5] Again asked for his reaction to this information, Mr. Vi said that he did not wish to comment as he knew nothing about it and “did not know the reason for Pang’s death.” What Mr. Vercken had noted, Mr. Vi added, was new to him.

Khieu Samphan’s DK-era Lambretta car was the next topic to which the defense counsel turned. Noting Mr. Vi had testified about Mr. Samphan’s car and driver arrangement during the DK period, Mr. Vercken asked him to contrast Mr. Samphan’s arrangement to that of other leaders. Mr. Vi said that “there were no people escorting [Mr. Samphan] other than a single driver.” This situation was unlike that of the other leaders, whose cars were always followed by “at least another vehicle.”

Turning back to Mr. Vi’s testimony from Tuesday concerning the three layers of guards at K-1 Office, Mr. Vercken asked the witness to confirm the various details of those arrangements. Mr. Vi said that he stood by his statement, although his testimony concerning the number of guards was a “rough estimation” and may have been incorrect.

In response to a question from Mr. Vercken, Mr. Vi testified that he did not know whether vehicles needed to be inspected when passing through into the third layer. However, as for the front entrance of K-1, this would be guarded and needed to be opened “when people were coming and going.” Mr. Vi confirmed that the guards “did not dare” inquire with visitors as to the particulars of their visit.

As to the numbers of people working at K-1, Mr. Vi said that the building was divided into two floors. On the first floor, there were about “10 people” working in each section, including “the cleaners, the delivery people, people who kept the garden well organized, and also the guards.” The second floor was the same, he went on, “there were cooks; there were people who raised the domestic animals and the pigs. At the same time, they had two jobs: working as both cooks and also as bodyguards.” This answer seemed to frustrate Mr. Vercken, who said that Mr. Vi’s answer was confusing and it appeared that the witness was not able to answer his question. Was he able to answer the question or not? the defense counsel pressed.

International Senior Assistant Co-Prosecutor Dale Lysak objected that this question was inappropriate and repetitive. Mr. Vi had answered the question, he said, including by supplying precise numbers. The president overruled the objection, however, and directed Mr. Vi to answer Mr. Vercken’s question. Mr. Vi duly advised that “on the first floor, there were about 10 people, and on the second floor, there were about 50 to 60 people.”

The president advised Mr. Vercken to move on, who did so by asking Mr. Vi to provide his comments as to the third floor at K-1. However, before Mr. Vi could respond, the president interjected to advise that there might be some confusion as to the difference between the floors of the building at K-1 and the compound’s layers of security, repeatedly drawing his hands in wide circles as he did so and explaining that this owed to the same word being potentially used in Khmer to mean both things. Conceding this possibility, Mr. Vercken asked Mr. Vi to disregard the issue of the number of guards at K-1 and instead advise, if he could, the number of people at K-1 who were not guards. Mr. Vi advised that he was not aware of this.

Inquiry into Particulars of the Witness’s Interview with the OCIJ

Moving away from the DK era, the defense counsel turned instead to the subject of the witness’s interview with the OCIJ and the number of times they interviewed him. Mr. Vi recalled, when asked, being advised that the interview would be audio recorded. Upon hearing this, Mr. Vercken queried whether, although Mr. Vi’s written record of interview was dated December 5, 2007, he may have met with OCIJ investigators more than once, such as the day before the recorded date. Mr. Vi advised that he recalled meeting with some people before the OCIJ interview, but he did not recall whether they were OCIJ investigators or attached to the ECCC at all. However, he met with the OCIJ only on December 5, 2007.

Mr. Vercken noted that the witness had been interviewed by Stephen Heder and another OCIJ investigator named Chan. In this interview, Mr. Heder had asked the witness a question about a person “referred to yesterday.”[6] It was for this reason, Mr. Vercken explained, that he had asked the witness about whether he had met with the OCIJ prior to December 5, 2007. Mr. Vi said that he did not recall this. He recalled meeting the OCIJ on December 5, 2007, although he also added that he was interviewed by the OCIJ “two days later.”

Asking the witness to set aside the question of dates, Mr. Vercken focused instead on the fact that the witness had just referred to two meetings and asked for further details of these. Mr. Vi advised that he did not remember on “how many occasions [the OCIJ investigators] saw me.” Next, Mr. Vercken asked whether Mr. Vi could recall discussing “facts between 1975 and 1979” or “substantive issues” with the OCIJ investigators at a preliminary meeting before the official OCIJ interview. The witness variously denied having any recollection of this, stated that he could have forgotten, and opined that “maybe” he spoke of such things.

Flight to the Jungle with Khmer Rouge Leaders

Returning to the DK period, Mr. Vercken asked the witness whether he fled with the leaders of the Khmer Rouge to the Cardamom Mountains. Mr. Vi agreed that he did so. Asked why, the witness explained “I had no choice. I had been working as a bodyguard for a three year period, and when we fled Phnom Penh, I was still loyal to them, and I gave protection to them until the 1990s. I had no intention to run away from them as I still maintained my job [as bodyguard].”

Finally, Mr. Vercken stated that when Mr. Vi was interviewed by the OCIJ, he said that the first time he heard of a famine that may have plagued Cambodia during the DK period was over a radio broadcast in 1980 or 1982. Mr. Vi confirmed, when prompted, that he stood by this statement and had not received such information before 1980 to 1982.

Further Clarifications from the Ieng Sary Defence Team on the Set Up and Operations at K-1

National Co-Counsel for Ieng Sary Ang Udom stood to put a few questions to the witness. He advised that his questions would focus on clarifying certain points of the witness’s testimony concerning K-1 Office. Mr. Udom began by noting the earlier confusion between the words “layer” and “floor” and asked whether the witness agreed that the Khmer word he had used – choan –should in this case be interpreted as “layer.” Mr. Vi agreed with this.

Mr. Vi replied, in answer to a second question from Mr. Udom, that the first layer of security was “inside the fence of the compound” and that “once you crossed the compound, you would reach the second layer.” From the second layer, he continued, you could not see the “tall high wall” of the first layer. Mr. Udom asked if it was possible to see the first floor of the K-1 building from the second layer. Mr. Vi said that if they were close to the fence, they could see the third floor of K-1, and if at a distance, they could also see the second floor, but they were unable to see the first floor.

The defende counsel noted that according to Mr. Vi’s prior testimony, all of the co-accused —namely Mr. Sary, Mr. Chea and Mr. Samphan — had entered K-1. He asked if the witness knew the reason for their visits. Mr. Vi denied this. He also denied, when asked, being able to overhear any meetings inside the K-1 building. After the senior leaders left the compound, Mr. Udom asked next, was Mr. Vi ever informed of them just having had meetings inside the building? The witness also denied this.

Mr. Udom asked Mr. Vi to advise the Court of the purpose of the senior leaders’ visits to K-1, Mr. Vi said that they were “coming to work.” Pressed as to what this meant, the witness said that the leaders were coming for meetings. However, he again confirmed that he was unable to hear inside the K-1 building from his guard post. Mr. Udom finally asked whether the witness learned through any means the purpose of the meetings and what kinds of decisions they made. Mr. Vi replied that he “could not grasp” this.

This concluded the parties’ questions to the witness and as such, he was duly dismissed, after which the Chamber took a slightly early morning recess.

Witness Ong Ren Testifies about Early Activities of the Khmer Rouge Army

Following the mid-morning break, witness Ong Ren took the stand. The president was the first to question him, seeking a few biographical details. Mr. Ren advised that he was born in 1950 in Kampong Speu province. He now lives in Trapeang Sar district in Otdar Meanchey province where he works as a farmer and serves as a member of the district council. He is married to Tek Roath and they have four children. Mr. Ren confirmed with the president that he was interviewed by the OCIJ on three occasions, if he remembered well. He had read the written records of these interviews and confirmed their accuracy.

National Assistant Co-Prosecutor Chorvoin Song began the Office of the Co-Prosecutors’ (OCP) questioning of Mr. Ren.[7] Ms. Song first noted that according to Mr. Ren’s testimony to the OCIJ, before 1975, he had worked in a special zone army.[8] Asked for details of this, Mr. Ren said that he first joined the army at Thmat Pong village and then moved to a location west of Kampong Speu. Battalion 3 was established at that time. Chong On was the person who invited Mr. Ren to join the revolution, and he had been responsible for the “district, the sector committee, and the military.”

The special zone “dealt with people … in order to make sure they were suitable for transfer to Phnom Penh,” Mr. Ren said. Specifically, this meant that they “gathered people together to join people so that we could strengthen the forces.” At that time, Mr. Ren said, Chong On was the person who was in charge overall and “we only reported to Chong On.”

Ms. Song noted that the witness had also previously testified that his division was from the special zone and that it eventually merged with another division from the north to form a regiment to attack Phnom Penh. She asked when this merger happened; Mr. Ren said that it was in “about 1972.” Was it Mr. On who ordered the formation of the regiment? the prosecutor inquired. Mr. Ren said that while he did not know for sure, he did not know who else could have done so.

According to Mr. Ren’s testimony before the OCIJ, he had referred to a Brigade 14. Asked what this was, Mr. Ren advised that some regiments were merged to form a brigade, and this brigade was tasked with “proceeding along National Road 4 towards Phnom Penh”; they were also tasked with engaging in “combat military training.” The brigade commander was So Sarun alias 05, he said. Mr. Ren also mentioned another person named San alias 06, although not this person’s position. Mr. Ren’s own role in the brigade was “to be in charge of a regiment.” He could not estimate the total number of soldiers in the brigade, but his regiment had 500 soldiers.

The prosecutor asked if Mr. Ren knew a soldier in his regiment named Kang Mut. The witness denied this. Ms. Song asked the witness for the name of his deputy. Ms. Ren advised that his name was Soeun.

“Brigade 14 engaged in the attack on Lon Nol soldiers,” Mr. Ren explained next. “The attack … commenced prior to 1974. … My regiment … was at the Trapaing Thaot railway station and Bat Doeng, … Basit Mountain, [and] Poun Phnom.” Ms. Song asked if his regiment also engaged in attacks at O Pa Mat and Thnal Tatoeng. Mr. Ren said that while this was the responsibility of Brigade 14, it fell to a different regiment than his.

“We were instructed to fight the Lon Nol soldiers, and that’s what we did. They were considered as our enemies,” Mr. Ren went on. He denied any knowledge of what happened to Lon Nol soldiers after they were captured, explaining that “my duty was at the front battlefield. As for the soldiers who were captured, they were sent to the rear, and I did not know what happened to them.”

The Fall of Uddong

In response to a question from the prosecutor, the witness was able to confirm, however, that Brigade 14 engaged in the fight around Uddong in 1974. Ms. Song asked Mr. Ren what kind of battlefield Uddong was, for instance, whether it was a “hot battlefield.” Mr. Ren said that “Uddong battlefield resulted in a number of casualties on the Lon Nol soldiers’ [side] and the destruction of a number of our vehicles. My regiment did not engage in that battlefield; the force [involved] was from the southwest.” Ms. Song asked whether the brigade was assigned to the attack at the Vihear Khpuoh temple. The witness denied this.

As for the preparatory plan to attack Uddong, Mr. Ren said that devising this plan was the “sole responsibility of the brigade commander” and Mr. On, and was made “prior to the formation of that brigade.” Ms. Song asked how Mr. Ren knew about the preparatory plan. The witness replied that this was because he “received orders from the brigade commander and Chong On … at Praim Pi Rong along National Road 6” at a meeting convened there.

“There was an overall plan for the brigade,” Mr. Ren explained in more detail. “The southwest force was to attack Uddong, and our regiment was to prepare for the attack on the south of Uddong.” However, “after the liberation of Uddong, I did not know what happened to the Uddong dwellers,” including the circumstances of their evacuation.

A Meeting with Son Sen in Preparation for the Attack on Phnom Penh, and the Attack Itself

Following the attack on Uddong, Mr. Ren said his regiment “received information that there was an arrangement from the upper level to manage the spearhead of the southwest force. It was the special zone force. The upper person that came was Son Sen alias Khieu.” Ms. Song asked if and how Son Sen relayed orders to brigade forces. Mr. Ren advised that “Orders were not delivered directly from the upper level,” but instead, through “a chain of command”: that is, orders from the upper level would be relayed to the brigade, and from the brigade to the regiment, and so on. He was thus “called by the brigade” to receive his orders. He qualified, though, that “it was not often that the upper level would call everyone” to deliver orders directly.

Communications within Mr. Ren’s brigade were undertaken “by radio only … There was a radio operator attached to the brigade. … When we talked about 05,[9] the message would be relayed to the brigade.” Ms. Song followed up by asking whether Mr. Ren ever received orders for attacks to be undertaken by his regiment via the radio. The witness agreed that this happened sometimes, but said that generally, meetings would be convened in order to relay such orders.

At this point, Ms. Song mentioned that in Mr. Ren’s second OCIJ interview, he said that the meeting with Mr. Sen was held 15 days before the attack on Phnom Penh, in Kampong Speu province.[10]She asked what was discussed at that meeting. Mr. Ren replied:

[It took place] to the south of Damnak Snak station … Son Sen called the brigades, the regiments and the battalions … to receive the plan. Number one was to prepare our political stance in anticipation of the attack on Phnom Penh. Number two was to prepare the forces into various groups. … Number three [was that] if we could advance in our attack, we would have to do our best to liberate the city. … He did not mention anything about the evacuation of people. He focused on … advancing on Phnom Penh to liberate the city.

Mr. Sen did not have a “proper office” at that time, the witness said; instead, “the meeting was held around bamboo trees.” There was no office because ongoing aerial bombardments made this impossible, the witness added. He did not know Mr. Sen’s role or rank at that time, but the person codenamed 06,[11] who “assisted in organizing the brigade,” said Mr. Sen “was known as Ta Venta, or ‘the man with glasses.'”

The prosecutor noted that the witness had previously testified that Mr. Sen had, at the meeting, shown a roadmap of Phnom Penh.[12] She asked whether Brigade 14 had prepared any attacks at specific locations. Mr. Ren said that “at that time, there were no proper locations, stations or barracks. [Things] were mobile, so we stayed in our various groups in order to avoid aerial bombardment.”

Continuing with hischronology, Mr. Ren described how Brigade 14 attacked Phnom Penh from “between Taing Krasaing pagoda.” His regiment attacked in the vicinity of Pochentong, he said, and the southwest force attacked along National Road 4. He explained, “We reached Pochentong, and I was wounded and I was hospitalized at the Taing Krasaing hospital. The advancement was made towards Phnom Penh but I stayed behind at the … hospital.”

Evacuation of Phnom Penh in the Southwest Direction

Ms. Song asked Mr. Ren how he would describe the situation of the evacuation of Phnom Penh. The witness prefaced his response by reminding the Chamber that he had been hospitalized at Taing Krasaing. However, he said that he did see people being evacuated. He asked where they were going but “got no answer” and learned only that “people were asked to move forward.” “Perhaps,” he mused, “people were asked to move forward to avoid bombs.”

Evacuees “walked and carried their luggage on pushcarts and bicycles. The roads were filled with crowds of people. The paddy fields were also packed with evacuees. There were no trucks,” Mr. Ren described. He had “no idea” whether people were pushed by Khmer Rouge soldiers because he “did not bear witness to this.” However, he doubted that people could have been “moved in such large numbers without a force behind them to compel this result.” Was it fair to say that people were forced to leave the capital, then? Ms. Song asked. Mr. Ren agreed that “without coercive measures, people would not have left the city. It is common sense that people would not want to leave their homes.”

Mr. Ren noted that at the same time as people were evacuating, he also saw other people “coming into the city” for reasons unknown. Overall, he concluded, “it was rather chaotic at that time.” Mr. Ren denied, when asked, seeing any checkpoints established to process people leaving the city.

Before moving away from the events of the evacuation specifically, Ms. Song asked the witness whether he knew of any practice to classify Lon Nol soldiers at the time of the evacuation. Mr. Ren said that “soldiers could be distinguished [as between] factions, but there was no practice of classification” at the time.

The prosecutor asked Mr. Ren where Brigade 14 was assigned within Phnom Penh. Mr. Ren said it was “tasked with patrolling on some roads” but noted again that he was admitted in Taing Krasaing hospital, adding that this was for about 17 days and that after his discharge, he did not return to Brigade 14. Instead, Mr. Ren was contacted through letter by the commander of the brigade, who called on him to start work. He explained, “I took a motorbike to see him, and he told me that the upper echelon would like to see me. I then was asked to station where we were tasked with protecting the city.”

At the time, Mr. Ren was stationed to the west of Borei Keila. He did not know what Borei Keila was used for at the time as he “had never been inside” it; he knew only that he would be stationed to the west of that location.

Mr. Ren said that he was then asked to “clean” an area in Phnom Penh. Ms. Song sought clarification on whether the witness was also tasked with standing guard or protecting any individual. The witness denied this, advising that forces would not be asked to stand guard; forces had to remain where they were and carry out “small tasks” at those locations.

Establishment and Military Structure of Division 801

Turning to a new line of questioning concerning military structure, Ms. Song sought to discuss with Mr. Ren a meeting held in July 1975, information about which was also published in a Revolutionary Flag issue.[13] However, before Ms. Song could proceed to her questions on this matter, Mr. Vercken objected that she was seeking to use a document without first allowing parties to have an adversarial discussion on their admissibility. Ms. Song responded by reiterating to the Chamber the relevant references for the document.

The president asked Mr. Ren whether he had ever seen the document before. Mr. Ren advised that he had not. Accordingly, the president ordered the document be removed from Mr. Ren and from the screen. At this juncture, International Co-Counsel for Ieng Sary Michael Karnavas chimed in with a second objection, suggesting that the prosecutor was leading the witness by first describing and then characterizing a meeting before proceeding with her questions on it.

Ms. Song duly offered to rephrase her questions and asked Mr. Ren whether he ever heard of or attended a meeting on July 22, 1975, with an audience of 3,000 or so people. Mr. Ren denied this. This prompted Ms. Song to note that in one of the written records of his OCIJ interview, he had been recorded as having said that Division 801 was appointed at a meeting attended by Pol Pot, Mr. Chea, Mr. Sary, and Mr. Sen.[14] Mr. Ren said that the meeting he was thinking of was not attended by “thousands of people” but only a few. This meeting was conducted at “the stadium.”

At the meeting Mr. Ren attended, Brigade 14 was elevated to become Division 801. Mr. Song asked whether anyone discussed the responsibilities and roles of the new division at this meeting. Mr. Ren responded, “During the meeting, there was a clear agenda. At the beginning, the agenda items were pronounced to us, and people addressing the meeting would be called to the stage. Pol Pot also had something to say about this appointment.” Ms. Song pressed on this point, asking whether anyone else also took the stage to share their points of view on this matter. Mr. Ren said, “Pol Pot was the one who made such pronouncement, and he discharged the duties to the division. No other people were involved in presenting the tasks to the division other than Pol Pot himself.” Ms. Song asked whether Pol Pot was the one who announced that Division 801 would be relocated to Ratanak Kiri. Mr. Ren agreed that “it was Pol Pot alone.”

Before the president adjourned the hearing for lunch, Mr. Ren described how Division 801’s eventual relocation to Ratanak Kiri occurred “about two months” after the meeting, with the witness recalling that “by September, we had to move,” with some soldiers on foot and others on bicycles. They reached Stung Treng province by November.

After lunch, the Trial Chamber public gallery received a colorful facelift care of approximately 150 students from the Pour un Sourire d’Enfant Institute in Phnom Penh wearing vividly bright orange, purple and yellow uniforms. The students heard Ms. Song resume her questioning of Mr. Ren by noting that according to the witness, a person named Som had introduced Pol Pot and the other leaders and received an appointment letter from them. The prosecutor asked who Som was. The witness responded that he was a member of the general staff in Phnom Penh. He was the one who announced the appointment of Division 801, with Pol Pot “making a supplementary announcement.” Som acted, in effect, as an “emcee of the meeting.”

The witness detailed how each regiment had to go to Ratanak Kiri first to “settle the location” set up for the soldiers. After this study trip, the divisions then moved to the province. Ms. Song asked Mr. Ren whether he knew who the Northeast Zone secretary was at that time. The witness denied any knowledge of this.

Ms. Song turned back to the meeting announcing the formation of Division 801, asking why it was that accused person Mr. Sary would have attended this meeting. Mr. Ren said that he “could not grasp” this.

At this point, the prosecutor honed in on a specific point of military structure, asking whether Division 801 received instructions directly from the Party Center. Mr. Ren said that he received instructions directly from So Sarun and did not know from whom Mr. Sarun in turn received his instructions; he also noted that the division had over 5,000 soldiers.

Asked to describe the structure of the regiment, the witness stated:

Below the division, there were regiments, and each regiment had three sections: logistics, military and politics. Then [there] came battalions with three separate sections as well. Then, there would be the platoon, with the same structure. There would be a chief, deputy chief and a member, and each structure would comprise of three lower structures. … The platoon comprised of three teams, or squads. … Each platoon contained between 35 and 36 soldiers.

After the creation of Division 801, the division was commanded by Mr. Sarun, together with San,[15] Mr. Ren advised. As for the witness himself, he was “in charge of a regiment.” His regiment was comprised of 430 soldiers.

The witness testified to the OCIJ, according to the written record of his interview, that he was assigned to a location near the Cambodia-Laos border.[16] Ms. Song asked whether the witness was required to report only to Sao Sarun or also to other commanders as well. Mr. Ren said that he was located in Sieng Pav in a district in Stung Treng province near the border.

At the time, Mr. Ren was required to report “directly to the division level.” As there was a lack of “modern equipment,” he occasionally had to walk for four or five days to deliver his reports to the division headquarters. However, when there was sufficient battery, these reports would be sent out by telegram. Ms. Song queried whether it was possible to deliver messages on horseback, but the witness advised that there were no horses then. Reports were filed only “as necessary” and occasionally “monthly.”

Meetings were held either “every month” or occasionally less regularly if they were postponed, Mr. Ren said. They would either take place at a division or at a regiment, depending on the invitation. It was beyond the witness’s knowledge how frequently division commanders reported to the upper echelon. They communicated either through telegram or radio but the witness was unaware to whom division reports were filed.

The prosecutor noted that the witness had previously testified seeing Mr. Sarun go to Phnom Penh for a meeting. She asked the witness if he saw Mr. Sarun going to meetings in Phnom Penh often. Mr. Ren said that he would see Mr. Sarun doing so “every month” or “every two months,” but “it was not often because the distance was far.” Mr. Ren himself did not go to attend any meetings in Phnom Penh.

Ms. Song then ceded the floor to her OCP colleague, Mr. Lysak. He began by putting Mr. Ren a follow-up question regarding the division secretary sending telegrams to the Center. Mr. Lysak queried whether the witness ever saw Mr. Sarun use a telegram machine to communicate with Phnom Penh. The witness explained that he was at Siem Pang and Ven Sai and therefore did not see Mr. Sarun using a telegram machine; he stayed at the division headquarters “for only a few days.” At this point, however, Mr. Lysak noted that in one of the witness’s OCIJ interviews, he testified seeing Mr. Sarun using a telegram machine.[17] He asked whether this refreshed the witness’s memory on this point. Mr. Ren responded that he “did not see any messages sent,” although he did see a telegram machine.

Follow-Up on Various Issues Including the Identities of Khmer Rouge Cadres

Mr. Lysak asked Mr. Ren whether Chong On, the person who introduced the witness to the revolution, was the person who later became the Minister of Industry. Mr. Ren said that he did not know about this but knew this person was in charge of the area to the west of Phnom Penh, that is, west of Bat Doeng.

The prosecutor left this issue and moved on to the witness’s testimony concerning Son Sen coming to take charge of the brigade. He asked whether, after this, the brigade commander continued to report to Mr. On or whether he reported directly to Mr. Sen. Mr. Ren clarified that it was the latter, and Mr. On “no longer had anything to do with the brigade.” The witness also advised that Mr. Sen’s headquarters were located to the south of Damnak Snak railway station during this period. However, there “was no proper base or headquarters”; instead, they “stayed in the jungle and the bushes there.”

The next issue for clarification concerned the witness’s repeated mention of a person named Sanalias 06. Asked for more details about San’s role, Mr. Ren responded that San had led one battalion while Sarun had led another, and Brigade 14 was created by combining the two battalions.

On the subject of Sarun, Mr. Lysak queried whether Sarun ever attended meetings with the general staff when he went to Phnom Penh. Mr. Ren denied knowledge of this but said that his understanding was that “the heads of brigades had to come to Phnom Penh to work.” As an afterthought, the witness mentioned that at that time, “communications were difficult” generally. The prosecutor asked whether Sarun ever relayed to the witness orders that he had received in Phnom Penh. The witness responded that “if the matter was mainly about rice production, then the heads of divisions would be contacted by radio to come to Phnom Penh.” Mr. Lysak clarified his question, querying whether Sarun convened meetings concerning his meetings in Phnom Penh. Mr. Ren said that “if the matter was not that urgent, upon returning from Phnom Penh, he would not convene any meetings,” but conversely would do so where the matter was urgent. One example of an urgent matter was “enemies … invading at the border.”

At this point, the president granted permission for Mr. Lysak to show Mr. Ren minutes of a August 30, 1976, meeting of secretaries and deputy secretaries of divisions and independent regiments.[18] In the relevant section of the report, a “Comrade Run” was discussing the situation at the Lao border.[19] Mr. Lysak asked Mr. Ren whether this person was So Sarun. The witness responded by way of reiterating that Sao Sarun was the head of the division. Taking a different angle, Mr. Lysak asked whether the areas discussed in the report were areas under the responsibility of the division. Mr. Ren said that conflicts that happened at the border took place in areas other than areas for which the witness and his division were responsible.

The prosecutor referred to another section of report which mentioned a “Brother 89.”[20] Mr. Lysak asked whether he knew who Brother 89 was. The witness denied this. This prompted Mr. Lysak to query whether the witness was aware whether Son Sen had another alias other than Khieu, such as a code number. The witness denied this, advising that the only codenames he knew of were 05 and 06 and he did not know of any such coding for Mr. Sen.

Mr. Lysak was granted permission to show the witness another report, namely a March 11, 1976, report from Division 801 to Brother 89.[21] The prosecutor first noted that the report was signed Thin and asked the witness who this was. However, this elicited an objection from National Co-Counsel for Nuon Chea Son Arun. He said that he understood that the practice applied “all along” by the Chamber was to first ask the witness whether he knew the document in question before proceeding to substantive questions on it. Mr. Lysak replied that there had been a number of exceptions to that, such as matters where a witness had direct knowledge and could therefore provide a report. In this case, Mr. Lysak said, there was a “direct connection” between the documents and the witness and such uses of documents had been allowed.

The Trial Chamber judges huddled in conference to deliberate on this objection, with Judge Silvia Cartwright resting her chin on her hands as if in thought. After a few minutes, the judges took their seats. The president advised that Mr. Arun’s objection was not sustained, as this was a “unique case” and the document Mr. Lysak sought to use related directly to Mr. Ren’s military unit. As such, the use of the document was permitted.

As the president noted that Mr. Ren appeared to have forgotten the question, Mr. Lysak repeated his question concerning the report signatory, Thin. Mr. Ren answered that Thin “worked at the regiment — what we called Regiment 83 of Division 801,” also explaining that he understood the question but had not responded as he did not see the red light on his microphone. Thin reported to Mr. Sen, who the witness now said had the code number 89. Was Thin the secretary of Regiment 83? Mr. Lysak queried. The witness confirmed this and added that Thin was “assigned from Phnom Penh like I was.”

This prompted the prosecutor to inquire as to the regiment number of which Mr. Ren was secretary. The witness advised that he was in charge of Regiment 82, explaining that it was stationed at the border in Siem Pang district.[22] When his regiment was established, the secretary of Regiment 81 was a person named Meut, Mr. Ren said in response to Mr. Lysak’s next question. Mr. Ren also advised that Meut’s position was created at the same time as his own.

Paragraph five of the report signed by Thin also mentioned that “Brother 05 is visiting all regiments with an aim to educate on the Communist Youth League,” Mr. Lysak noted. He then asked whether Brother 05 was Mr. Sarun. The witness confirmed this and also confirmed, when queried, that Mr. Sarun did provide political education to his regiment and recalled attending one such session while he was at Siem Pang. Sessions ran for two days and covered such subject matter as “strengthening the forces … and about the Party’s line, and other details. We were asked to make sure that the Youth League could build [us up].”

The prosecutor noted that in one of the witness’s OCIJ interviews, he had testified that Sarun taught people not to hit or question hostages or potential spies but to send them “to the top.”[23]Mr. Lysak asked what it meant to send people “to the top.” Mr. Ren explained:

When it comes to hostages, we referred to people arrested at the battlefield. Spies referred to people who were spying on us. We received instructions from our superior that if any unit had arrested any of them, we were asked not to beat them but have them sent to the division who would send them further to the upper echelon.

Mr. Lysak asked the witness to clarify the order of locations where the witness stayed and positions he held during the DK regime, noting his recollection that the witness was in Phnom Penh, then Siem Pang, then Ratanak Kiri, then Phnom Penh. Mr. Ren clarified that before he went to Phnom Penh, he was asked to go to Ven Sai.[24] There, the witness said, he was asked to replace the person known as 06, or San. He continued “I asked what I was expected to do, because San had already been removed to Mondulkiri. I was told that I was to replace him. … The upper echelon assigned me to the task of replacing 06.”

Insights into the General Staff in Phnom Penh

The prosecutor moved to a new line of questioning concerning the general staff in Phnom Penh, first asking for the witness’s report as to their role. Mr. Ren replied that “less than one week” after he arrived in Phnom Penh, he became sick, and at this point, “stayed with the general staff.” There was “no official announcement” concerning the appointment of the general staff, the witness said. It comprised Som, Nat and various other individuals, he said, but he did not grasp their roles. “Because of my poor health, I did not engage in any activities,” he added. Mr. Ren responded that “as far as I knew, Sao, Vat and Chan were members of the general staff at that time.”

The general staff’s office “was located behind the Ministry of Defense,” Mr. Ren said next. When he stayed there, he added, “there were three general staff members and a total of 30 general staff.” Queried about whether it had a telegram or telegraph machine, Mr. Ren responded that “I never went upstairs to see, however, I heard the sound of a telegram machine … The main point at the time was to maintain secrecy, so if I did not have any duty there, I would not go there.” He added that it was possible to deduce that a telegram machine was there because “you could see the wires going into that room.”

Asked whether one of the main responsibilities of the general staff was to provide weapons and ammunition to the divisions and regiments, Mr. Ren said, “I never saw any representative of the general staff going down to our regiment to distribute any weapons or ammunition because that was the responsibility of the logistics sections. But indeed, there was an arrangement between the general staff and the logistics.”

Disciplining and Purging of Cadres

After the mid-afternoon break, Mr. Lysak advised that he wished to move to a new issue, namely the disciplining and purging of cadres. He noted that according to the witness’s previous testimony, he had mentioned being shown a telegram while he was studying in Phnom Penh, detailing the arrest at Ven Sai of Keo Saroeun alias Khieu, who was accused of having committed a moral offense with Neary[25] Heng. The telegram was from the office at Brigade 801 in Ven Sai, Mr. Ren had said, and the witness had also said that Office 870 had delivered this telegram to Mr. Sarun.[26] Asked for further details about this, Mr. Ren advised that Mr. Saroeun had been the head of Regiment 81 but had already left to become a member of the division committee. As to what a “moral offense” was, Mr. Ren said that this was the action undertaken with Neary Heng.

In his same OCIJ interview, the witness had also testified that Office 870 was involved in a telegram concerning the discipline of Mr. Saroeun, Mr. Ren had responded that Office 870 had to be involved where the offense concerned cadres accused of misconduct, in order to make a final decision.[27] Mr. Lysak asked the witness what led him to this point of view. The witness explained, “The commander or secretary of the division who had to come to Phnom Penh to study … could only come to those sessions through radio communication from 870. The reason that I said that Keo Saroeun could have been arrested was because he used to say that he had moral misconduct.”

The president granted the prosecutor permission to show a series of documents to the witness. The first was minutes of a December 16, 1976, meeting between Division 801 and Brother 89.[28] Mr. Lysak noted that a heading in this document was entitled “Problems Concerning Keo Saroeun” and that there were also comments from Brother 89 indicating that Mr. Saroeun should be left alone “for the time being.” Mr. Lysak also noted that the document referred to Comrades Soeun and Thy. Stopping at this point, he asked who these two people were. Mr. Ren said that he did not know. Mr. Lysak asked whether the witness recalled a Soeun who was the deputy of his own regiment for a period. The witness confirmed this. The prosecutor queried whether the “problems” concerning Mr. Saroeun were the moral offenses discussed earlier. Mr. Ren denied knowledge of this on account of his being in Phnom Penh for study. Referring back to the earlier mentioned telegram concerning Mr. Saroeun, Mr. Ren said his belief was that the telegram was from Office 870 and that he may have received copies of it from Brother 05.

The next documents Mr. Ren was asked to peruse were two reports dated March 24, 1977[29] and March 29, 1977, respectively.[30] Mr. Lysak first asked the witness who signed and sent these reports. The witness responded that the reports were signed “Comrade Run” or So Sarun who was the head of the division. The witness also confirmed, when queried, that he recognized Mr. Sarun’s signature. The prosecutor noted that handwritten annotations on the report indicated that they had been sent to Angkar. He asked the witness whether he recognized who, from the handwriting, had sent the reports on to Angkar. The witness denied knowledge of this.

As for the substantive content of the reports, Mr. Lysak directed Mr. Ren to the first report dated March 24, 1977 and its discussion of the capture of seven Yuons.[31] The prosecutor asked the witness who would have been responsible for arresting and interrogating the Vietnamese. Mr. Ren denied knowledge of this because “the arrests were not made at my unit. … I did not know where or to whom the documents could have been sent to.”

In the second report dated March 29, 1977, Mr. Lysak said, a detailed report was set out describing enemy movements at the base. He asked how it was that the division secretary could have reported on enemy movement at the base. Mr. Ren reiterated that “my regiment was far away from other regiments, and [on the question of] what happened under the responsibility of a respective regiment, that regiment would have to report” up the chain of command.

In the “Miscellaneous” section of that same report, Mr. Lysak advised, one of the notations indicated that at the Siem Pang base, “the army should go and meet with the people to help control the people.”[32] He first asked Mr. Ren whether the Siem Pang base was the witness’s location. The witness seemed to acknowledge this since he answered that “when I was [at Siem Pang], nothing complicated happened” such as “clashes with the Vietnamese.” Therefore, Mr. Lysak went on, was it possible that the witness had already left Siem Pang by the date of this report? Mr. Ren confirmed this, since “if I were there, I would have known what happened. … What happened in the report did not happen during the time when I was there.”

Paragraph three of the March 29, 1977, report also described how the enemy was “smashed” without any interrogation, making it difficult to trace the enemy “strings.” Mr. Lysak asked the witness whether he knew whether, by the date of the report, Comrade Thin was still at Division 801 or had already moved on. Mr. Ren replied that:

[Thin] was in 801, unit 83. Later on, he was assigned as the head of sector in Ven Sai. I heard the secretary of my division talk about the reason he had to be moved to that location, because he told us that Thin was of Tampuan ethnic minority and he would be best located there.

Mr. Lysak asked whether it was generally necessary for enemies to be interrogated before they could be “smashed.” Mr. Ren said that he did not understand about this, although he did hear that in other units, “people kept disappearing.” However, he said that this did not happen in his own unit.

The prosecutor noted that the document had a reference to people going “against the revolutionary line.” He asked the witness whether the Party line was the same thing as the revolutionary line. Mr. Ren confirmed that it was “one and the same” but qualified that “the practice was sometimes inconsistent from the Party line, because there were distractions as well.”

Mr. Lysak asked if those who opposed the revolutionary line were considered enemies. Mr. Ren said that he could only testify about what happened in his own unit. Neither when Mr. Ren was at Ven Sai nor after he returned to Banlung[33] to work in Boeung Kanseng did he hear about such issues. He only learned later that there was a security center in Boeung Kanseng. “People came to me to request that I resolve their children’s issues,” he went on. Indeed, he recalled that on one occasion, concerning the issue of 20 people who had been arrested for stealing potatoes, he conferred with Brother 05 who advised that the 20 people be released.

Continuing his focus on the March 29, 1977, report, Mr. Lysak noted that in paragraph five of the report, it was stated that “newly implicated” people were also targeted. He asked what this meant. Mr. Ren said that he did not understand this issue and that “in fact, in my unit, there was no new forces. Here, they refer to old and new forces, and I do not get it.”

Implication of the Witness by Fellow Khmer Rouge Cadres and a Dramatically Avoided Arrest

Mr. Lysak noted how in one of the witness’s OCIJ interviews, he testified that Mr. Saroeun was called to Phnom Penh and then disappeared.[34] He asked Mr. Ren whether it was common that people would be called to Phnom Penh and then would disappear. The witness responded that he was “unsure how Kao Saroeun had been arrested” but thought that this owed to his having committed a moral offense. The prosecutor then asked whether the witness learned that he had been implicated by Mr. Saroeun after the latter had been arrested. Mr. Ren said that this implication was the reason he “was assigned to work at Boeung Kanseng.” The witness:

Did not know the reason why they had implicated me … and I thought it would not be long before I would be taken away … because when I returned, I was assigned about four or five days’ walk from my previous location. But then, nothing happened … so it was my conclusion that he was arrested because of that offense. That is all.

The witness had also testified to the OCIJ, Mr. Lysak said, that a second person had implicated him; someone named Sorn. Asked who Sorn was, Mr. Ren said that “he was in regiment 82, in charge of logistics.” Mr. Lysak asked whether Mr. Sarun showed the witness the confessions of Mr. Saroeun and Sorn, or just discussed them with him. Mr. Ren said he did not see the confessions but that Mr. Sarun “just told me that the situation was not that good and I was returned from Phnom Penh because I had been implicated.”

At this point, the president permitted Mr. Lysak to show the witness a typed S-21 prisoner list entitled Names of Prisoners Smashed on 21 May, 1977.[35] Mr. Lysak directed the witness in particular to prisoners numbered 183 to 191[36], noting that a person numbered 189 was identified as Keo Saroeun alias Seng. The witness perused the document with a somber face. After a short pause, he confirmed this this was Mr. Saroeun. The prosecutor then noted that the person at 184 of the list was identified as Touch Sorn. Mr. Lysak asked whether this was the same person as the Sorn who had reportedly implicated the witness. Mr. Ren seemed to confirm this, responding that “Touch Sorn was in charge of the logistics at Regiment 82.”

Mr. Lysak asked the witness if he knew any other people on the list. After the witness soberly perused the list for some minutes, the president interjected to ask the witness to focus only on the numbers advised on the list. Mr. Ren then responded that he knew only Mr. Saroeun and Sorn, stating that the rest were from different regiments in Division 801.

The prosecutor was granted permission to show the witness a portion of two S-21 confessions. The first was Mr. Saroeun’s, which Mr. Lysak noted had previously been shown to the witness during one of his interviews with the OCIJ.[37] Mr. Lysak advised Mr. Ren that the only portion he wanted Mr. Ren to consider was a handwritten note dated June 5, 1977, from Duch to “Brother” that noted that “there were up to 58 traitorous people embedded” in the Brother’s area, going on to name some of them. Mr. Lysak asked the witness to advise the date on which he had been advised that he had been implicated by Kao Sarun. Mr. Ren responded instead that he only knew one of the people who Duch had named as having been implicated by Mr. Saroeun. In addition, Mr. Ren thought it unlikely that all 58 people were from his regiment, since his regiment was far from Mr. Saroeun’s. After Mr. Lysak repeated his initial question, the witness advised that he thought he heard of his own implication in around “late 1977.”

The second confession Mr. Lysak showed the witness was of Sour Tun alias Mao, a Division 502 cadre. This confession contained a handwritten note from Khieu to Comrade Run dated June 2, 1977, on brown paper in red pen, asking the recipient to read the report and pick out people implicated from Division 801.[38] Mr. Lysak asked the witness whether he ever heard Mr. Sarun speak of other people who had been implicated in the division. Mr. Ren denied this, stating that he heard only of the arrests of Mr. Saroeun and Sorn. This prompted Mr. Lysak to ask whether the witness was told by Mr. Sarun how he learned that the witness had been implicated. The witness denied this, though speculating that it was “possible that [Mr. Sarun] had [Mr. Saroeun’s] confession with him.” All he was told, Mr. Ren said, was “that I had been implicated, that I should try to work hard, and that I should not go freely anywhere. I stayed in that location until the events that took place later on.”

Was there ever a time, later, when the witness was called to Phnom Penh? Mr. Lysak asked next. Mr. Ren replied:

About one or two months after I stayed there, and after I met with So Sarun [and heard] what he told me, the telegram machine broke. After it was fixed, a message was then decoded and he told me that 870 required me to go to Phnom Penh … the next day. Of course, I was concerned upon hearing that. I did not know what would happen. Because if Keo Saroeun went to Phnom Penh and he met that fate, I was afraid that I could meet the same fate, and in fact, at that time, he showed me the telegram in plain text and [it said] that I was required to go. …

When I arrived in Stung Treng, a plane was waiting for me. While I was in Kon Mom,[39] I saw a division vehicle coming, approaching me, and I was told that I should return immediately to Boeung Kanseng as a was brother waiting for me. When I returned, the brother told me that the situation was not that good and that I should not go to Phnom Penh and I should stay put with him. Later on, I went ahead for about half a kilometer, and then all broke loose, as the attack was on.

On this dramatic note, the president adjourned the hearing for the day. Hearings will resume at 9 a.m. on Thursday, January 10, 2013.