Scrutiny Over Investigative Procedures Punctuates a Long Day of Testimony

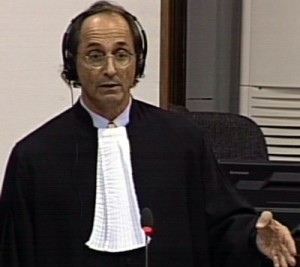

International Counsel for Ieng Sary Michael Karnavas requests transcriptions of the witness’s OCIJ interviews at the ECCC on Thursday.

A long hearing day unfolded in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Thursday, January 10, 2013, with witness Ong Ren providing a second day of detailed testimony on the authority structures and events of Democratic Kampuchea (DK).[1] Parties sought to clarify a wide range of issues with Mr. Ren, a former Khmer Rouge regiment commander, including the investigative procedures undertaken by the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (OCIJ) when it interviewed him in preparation for the trial. This discussion provoked a tense exchange involving the Ieng Sary Defense Team, the Office of the Co-Prosecutors (OCP), and the judges concerning requests for the preparation of transcripts of OCIJ interview audiotapes.

Mr. Ren also provided further insight into the precise details of the chronology of events in which he was involved during DK period and discussed a range of new issues. These included, notably, the witness’s alleged role in the People’s Representative Assembly in the DK, the American aerial bombing campaign in Cambodia, and the witness’s understanding as to the precise function and relative position of the Central Committee.

Nuon Chea Granted Leave to Participate from the Holding Cell

Over 100 high school students and their teachers attended the morning proceedings from Kandal Stung district, Kandal province. All parties to the proceedings were present this morning, according to an announcement from Trial Chamber Greffier Se Kolvuthy at the start of the hearing, with one exception: accused person Ieng Sary was participating in the proceedings from his holding cell.

Before questioning of Mr. Ren could resume, the floor was granted to National Co-Counsel for Nuon Chea Son Arun. He advised that according to the medical report prepared by Dr. Tong Hong, the treating doctor at the ECCC, Nuon Chea would be in a position to participate in the courtroom for 30 minutes, after which he should retire to the holding cell downstairs as his dizziness and backache prevented longer participation. Mr. Arun requested that Mr. Chea be permitted to participate from his holding cell.

Unlike similar past requests that Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn routinely granted without consulting his colleagues on the bench, today’s request precipitated a group deliberation, with the Trial Chamber judges huddling in conference at this point around their translator. After some minutes, Judge Jean Marc-Lavergne returned to his seat, though his colleagues continued conferring for another minute. The president then advised that the Chamber had received Dr. Hong’s medical report. Appearing to read from a prepared statement, he announced that in the interests of justice and in light of the medical report and Mr. Chea’s request, the request was granted.

Khmer Rouge Regiment Commander Ong Ren Testifies on the Treatment of Enemies

Witness Ong Ren took the stand, while International Assistant Co-Prosecutor Dale Lysak took the floor to resume questioning him. Mr. Lysak first noted that according to the record of one of his interviews with the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (OCIJ), Mr. Ren had testified hearing from Commander So Sarun about enemies such as “CIA, KGB, and the Yuon[2] enemies.”[3] Mr. Ren confirmed that these meetings were held at Ven Sai[4] and discussed the enemies and the need to “follow the activities” of them.

The prosecutor was permitted to show the witness a November 25, 1976, report to Brother 89 from Run at Division 801.[5] The prosecutor noted that at section two of this report, there was a discussion of “enemy infiltrators” and a report of combatants arrested at Regiment 83. Mr. Lysak directed the witness to section four of the report and its list of organizational measures, which specified:

- Suspected enemies were to be “absolutely arrested.”

- Suspected enemies were to have documents reviewed against them and be temporarily arrested.

- Those with “political tendencies” were to be “gradually arrested.” Anyone who continued to have faults after three sessions of reeducation was to be removed from the unit.[6]

The report also requested that “uncle” make comments and give directions. Mr. Lysak asked whether the measures proposed matters that could be decided at division level or whether the Center needed to approve such measures. Mr. Ren replied that nothing like this happened in his unit but they knew about “other events that happened outside our unit.” He reiterated that Mr. Sarun had requested him to monitor suspected enemies, before adding that there was “no such phenomenon in my unit” as the measures described in the report. He “could not grasp” whether Mr. Sarun took instructions from above or decided himself who ought to be arrested.

Further Clarification on Witness’s Time at the General Staff

Moving on, Mr. Lysak said that he wished to clarify the time period in which the witness spent time at the general staff in Phnom Penh. Mr. Lysak noted the witness had advised the OCIJ that he had been at the general staff in August 1977, but then in his testimony to the Chamber, had suggested that he may have already been there in March 1977. Asked for his comments on this, Mr. Ren said, “As I already stated, I left Siem Pang[7] in July 1977. July was the rice planting session. I left … for Phnom Penh to attend a study session.”

This answer prompted Mr. Lysak to explain that the witness had testified to seeing Som while at the general staff office. However, he explained, according to an S-21 prisoner list on the case file, an individual named Pech Chan alias Som, assistant of the general staff, entered S-21 on March 14, 1977.[8] As such, the prosecutor advised, Som would already have been gone before the witness arrived at the general staff office.

With this in mind, the prosecutor directed Mr. Ren’s attention to minutes of a meeting on September 19, 1976, between division secretaries[9] and, in particular, a handwritten distribution list in the upper right-hand corner of the first page. This list included “89, 81, Nat, Som, and Ren 801.” He also advised that this was the first document that they had found that seemed to list the witness’s name on a distribution list, comparing it with the lists of meeting minutes dating from September 1976[10] and September 16, 1977.[11] After this preamble, Mr. Lysak asked the witness to clarify when he had left for Phnom Penh. Mr. Ren insisted:

I remember having left Siem Pang on July 1977. It was during the rice transplant season. About a month after rice had been transplanted, I had to go to Phnom Penh. My personal observation is that in 1976, I was a farmer in Siem Pang. In 1977, I also did farming in Siem Pang. Only in July 1977 did I move.

Continuing to investigate Mr. Ren’s memory on this matter, Mr. Lysak presented the witness with a series of documents. The first was a mid-December 1976 document the distribution of which listed a Ren from 801.[12] The prosecutor asked whether there was any other person named Ren from Division 801 who was, for a period, located at the general staff. The witness replied that there was only him. Mr. Lysak asked whether the documents refreshed Mr. Ren’s memory as to when he was at the general staff, and whether he was the person on the distribution list. The witness responded, somewhat confusingly, that he “never received documents from 801.” Mr. Lysak noted that the distribution list also included a person whose code number was 81. He asked if the witness knew who this person was. The witness denied both this, and also, when asked, knowing a person at the general staff office known as Siek Chhe alias Tin.

Continuing to investigate Mr. Ren’s memory on this matter, Mr. Lysak presented the witness with a series of documents. The first was a mid-December 1976 document the distribution of which listed a Ren from 801.[12] The prosecutor asked whether there was any other person named Ren from Division 801 who was, for a period, located at the general staff. The witness replied that there was only him. Mr. Lysak asked whether the documents refreshed Mr. Ren’s memory as to when he was at the general staff, and whether he was the person on the distribution list. The witness responded, somewhat confusingly, that he “never received documents from 801.” Mr. Lysak noted that the distribution list also included a person whose code number was 81. He asked if the witness knew who this person was. The witness denied both this, and also, when asked, knowing a person at the general staff office known as Siek Chhe alias Tin.

Mr. Lysak presented the witness with minutes of an October 9, 1976, meeting with Son Sen discussing meetings that would be held at the general staff.[13] Mr. Lysak directed the witness’s attention to lists of participants relating to two general staff study sessions that were held on October 20, 1976,[14] and November 23, 1976,[15] respectively. Turning to the first list, Mr. Lysak asked the witness to focus on participants 92 to 122 on the list and advise the Chamber whether he recognized fellow cadres from Division 801. The witness advised that he could recall the listed people named Run, Horn, Kheng, and Chhaom.

Directing the witness to the second list, the prosecutor asked the witness to repeat the exercise with respect to numbers 33 to 63 of that list and see who he recognized. Calling out names while he perused the list, Mr. Ren reported that he recognized the names Run, Keo, Pro, Soeun, and Sorn of that list. Mr. Lysak then asked, more generally, if the witness remembered these study sessions. The witness denied this.

As for why his name was not on the list, Mr. Ren stated, “The only thing I know was that my name did not appear in the list.” He elaborated, “Each session was attended by at least a focal person of the unit.” Mr. Lysak asked if it was possible that the reason his name was not on these lists was because he was already assigned to the general staff at that time. Mr. Ren clarified that “there was no proper or formal appointment.” This prompted the prosecutor to advise that there was an additional document that recorded the list of Division 801 attendees at the general staff study sessions, and its contents were consistent with the two lists discussed.[16]

Still keeping with the theme of determining when the witness was at the general staff, Mr. Lysak requested permission to show the witness a September 21, 1976, report from Comrade Ren of the general staff office regarding a “lifestyle meeting” at Division 450[17] and an October 1, 1976, report from Comrade Ren concerning a “lifestyle meeting” at Division 170.[18] However, before the president addressed this request, he ceded the floor to National Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Kong Sam Onn. Mr. Sam Onn argued that Mr. Lysak’s practice of making observations about documents to the witness a moment ago was not appropriate and that he should have gone straight to questioning the witness and left such presentations to another session – presumably, a document hearing. Mr. Lysak responded that this issue had been discussed already and the practice permitted. The president granted the prosecutor leave to present the reports to the witness.

Accordingly, Mr. Lysak asked the witness whether he was ever asked to attend “lifestyle meetings” at Divisions 450 and 170 and to report to the general staff on those meetings. At this point, there was nothing audible in the English translation, although in the Khmer translation, the translators could be overheard discussing the fact that they did not understand what the prosecutor had said. Mr. Lysak then put a reformulated version of his question to the witness. Mr. Ren confirmed that he did attend these meetings but stressed that attending these meetings had originally been Som’s responsibility; however, as Som had “prior engagements,” the witness attended on his behalf. As for what he was tasked with doing there, Mr. Ren said that he was to “be at the meeting as an attendee only. … It was up to the chairman of the unit to propose items for the agenda. We [simply] had to report to the upper echelon” on what was said and decided at these meetings.

Review of Documents Allegedly Written by the Witness

At this point, the prosecutor showed the witness a series of documents in relation to a new line of questioning, foreshadowing that the documents appeared to have been written by the witness. The first document was minutes of an October 18, 1976, meeting of division secretaries, and Mr. Lysak directed the witness in particular to a section where Brother 89 provided comments and discussed the establishment of a committee consisting of “Nat, Thin, Ren, Som, and the division secretaries” to look at how to “better protect Phnom Penh.”[19] Mr. Lysak asked the witness whether he recalled being assigned to such a committee. Mr. Ren said that Nat and Som were involved in it but he was not, as he “was at a separate location with another two people.” In addition, and as he discussed with the OCIJ, there was one occasion where he was asked to go and protect a location;[20] however, on his arrival, the enemy had already gone.

The next document to be shown to Mr. Ren was a November 14, 1976, report by Comrade Ren of the general staff office. Mr. Lysak noted that this document referred to a cadre named Chaut[21]and people he had implicated in Divisions 450, 310, Commerce, and other locations.[22] The prosecutor asked Mr. Ren to comment on this, but he was unable to do so. Mr. Lysak asked whether the witness recalled having discussions with a Brother Soeun from Division 450. The witness denied this and advised that he only attended one meeting.

“Comrade Ren of the general staff office” had also been identified as the author of a November 25, 1976, report concerning working with An Un[23] of Division 310, and discussing Chea, secretary of battalion in Division 310, and Horn, a soldier in a battalion in Division 310, the prosecutor said.[24]When asked, the witness denied knowing anything about the making of this report. He said, instead, that while he knew Un, he did not know the other two people. Moreover, “activities in a division were only known … to the staff in that division.” He added, “Sometimes I was advised to attend this meeting or that meeting when I was free,” but he did not recall this particular meeting.

Another report from Comrade Ren was dated December 24, 1976, and again concerned Division 450. According to Mr. Lysak, this particular report related specifically to conditions at the division and the author’s work with Brother Sung and Brother Yom. The report also contained a proposal to remove a Comrade Lum[25] from the unit.[26] Asked whether he could recall anything of this report, the witness said he learned about this event when he met with Son and Yom. He continued to explain, “While I was at the general staff, I was asked to assist them, but I only made the report, I did not make the decision.” Nat of the general staff was the one who asked him to make this report, he said. At this point, Mr. Lysak advised the Chamber that the case file contained an S-21 prisoner list indicating that Mao Sokha alias Lum,[27] identified as an assistant at Division 450, entered S-21 on December 31, 1976,[28] just days after the report from Comrade Ren.

The prosecutor requested leave to show the witness two more reports from Comrade Ren: one dated March 12, 1977,[29] and another dated October 30, 1977.[30] However, the president first asked Mr. Lysak to clarify how much longer he planned to question the witness, as the combined time remaining for the OCP and the Lead Co-Lawyers for the civil parties was only 14 minutes. The prosecutor advised that the Lead Co-Lawyers had agreed to allow Mr. Lysak to use all the remaining time.

The first report, Mr. Lysak continued, described the overall situation in Divisions 310 and 450, stating that the witness had met with the brothers and sisters “in accordance with the views and instructions of the organization.” Asked what he could recall of this meeting, Mr. Ren said:

Regarding the overall situation in the unit, due to the changed situation, Som said that I should go to Chbar Ampeou to meet with 170 to assist them. The situation was to monitor the enemies’ activities. As for the military activities, there were movements, and things changed. So I was instructed to observe and monitor the internal activities as well as the external activities and whether those people in the units abided by the discipline. Yes, I did take that action.

Mr. Lysak asked whether the witness had been aware that the secretaries of both divisions had just been purged. The witness said that he “could not grasp the situation back then” and “did not know whether there were issues within any specific regiment.”

As for the second report, Mr. Lysak noted that it concerned the removal of three categories of “bad elements.” The first category was persons to be sent to Duch; the second, to Brother Huy; and third, to the farm paddy at Prey Sar. “I did not have any authority to propose that people be sent to S-21 or a rice field,” Mr. Ren asserted, also stating that he never ordered for people to be sent to Duch, as this was Som’s authority. In fact, Mr. Ren explained, the situation would be as follows:

In a cooperative, in order to work in a rice field, if a plow was broken, did it come to the attention of the general staff without a report from the village or cooperative chief? The village or cooperative chief would not know about this unless it was reported by the group chief. So I made a report to Som, and Som further reported to the upper echelon. Whatever decision they made was beyond my knowledge.

Perhaps sensing some discomfort on the witness’s part, the prosecutor took the opportunity to thank the witness for his response and reassure him that he was not being accused of anything. He then asked whether Mr. Ren had written the report “for someone who was seeking the authority to have these people removed.” The witness responded instead that people may even have used his name as the person who prepared a report.

Establishment and Operation of the People’s Representative Assembly

Finally, the prosecutor directed the witness’s attention to the People’s Representative Assembly, asking the witness whether he was aware of this entity by 1976. The witness said that he “did not actually know about it. I heard people talking about it, but I never actually attended any of the events.” Mr. Lysak asked whether the witness knew that when the assembly was elected, the witness was named as one of the representatives of the Cambodian Revolutionary Army within that assembly. Mr. Ren responded, “My commander told me about that. In my division, he said, only he, 05, and his deputy, 06, were named. But after, we were never called to any meeting.” Was there actually any election or voting for this assembly in the witness’s location, Stung Treng province, in March 1976? Mr. Lysak asked. The witness responded:

No, there was no meeting or election held there. The work was decided in a meeting, and then instructions would be relayed in the announcement. Under the regime, there was no election, according to my observations. Usually decisions would be announced after it was decided, and instructions were in writing for such an announcement. There was no open decision-making of that sort. However, I would not have any idea of the process that was carried out at the base because I did not see any gathering or a major meeting in making a decision.

Neither, said the witness, did he ever attend meetings of the People’s Representative Assembly. Moreover, he added, only Mr. Sarun and his deputy San were named in the assembly, not him. He also denied ever being presented any legislation of the assembly for consideration and approval. This concluded the OCP’s questions, and precipitated the Chamber’s adjournment for the mid-morning break.

After the hearing resumed, the floor was ceded to Judge Lavergne to question the witness. Keeping to the most recently mentioned issue of the People’s Representative Assembly, the judge asked the witness to clarify if he had learned that his name was included in the list of representatives after the assembly was established. The witness agreed that he had learned of this from his commander “only later after the meeting.” He added, “Despite the fact that my name was included, I was never called to any meeting.” As such, he had no idea at all of the “functions or the role of the assembly” at the time, and indeed, was still unaware of this.

This answer prompted the judge to point out that there were two potentially relevant documents on the case file. The first was a report of a BBC World Service broadcast on March 22, 1976, which detailed the findings of an electoral commission responsible for the elections and was signed by Khieu Samphan, Sok Naot, and Sok Chut. Based on the electoral scrutiny of the population, the report said, out of a population of 7.78 million people, over three million voted, and 250 representatives were overwhelmingly elected. On the last page of this document, the judge highlighted, one of the names of representatives was listed as Ong Ren.[31] He asked the witness if he was aware of the release of this report either on the radio or sent to the witness in a report. Mr. Ren denied this.

The second document, from Tuol Sleng, related to the Assembly of Senior Representatives of the People and the first congress held in April 1977.[32] On one page of this document, the judge noted, there was a photograph. The description of it detailed representatives attending this congress. He asked the witness to give his comments about the photograph. Mr. Ren responded by insisting that he did not know about the assembly until his commander told him about it and that “I have never seen this document previously.”

Finally, Judge Lavergne asked the witness whether he knew the role of this assembly regarding appointments to, for example, the cabinet, the judiciary, and the head office regarding internal and foreign policy orientations for the new government and State Presidium. He asked whether the witness knew anything about these matters. Mr. Ren denied this, stating, “In fact, what I knew was really limited. I knew about the organization of the groups, squads, or the division,” but not about organization at the upper level. He also did not know anything about “meetings gathered to make certain decisions.”

Further Details on the Witness’s Early Experiences

Beginning the cross-examination, Mr. Arun took the floor. Explaining that he was unclear as to the witness’s personal biography, he asked the witness to offer some further biographical details, namely when he joined the revolution and what his initial roles were. Mr. Ren obliged, stating:

Initially, Heng, the commune chief of my village, said that we shall consolidate our own forces. Of course, I too wanted to consolidate our forces as one solidified force so that we could achieve our common goal. That was the advice from him. Later, and I cannot recall the date, there was a riot and he said that we could no longer stay in the village so we fled to the jungle. That was in around 1968. A few months later, I returned to my village. By [1969], I went again.

In 1970, there was a coup d’état to overthrow Sihanouk. Based on his appeal, I joined and I stayed at the Dong Tong[33] pagoda. Later on, at the Bat Doeng railway station, as I indicated earlier … I performed my duties as instructed by [Chong On and others]. Later on, they organized into squads, teams, and I was assigned to Vichetra Mountain[34] to be based there. I was at Road 26 back then. Later on, I was assigned to be in charge of an independent company. …

I was based to the west of Vichetra; that is west of the Basit Mountain. Initially, when I went there, there were only merely about 10 people while I met with Chong On. He instructed me to stay there. Later on, there were forces from the southwest. Then the forces kept increasing and formed a company. I was with Soeun and Noeung in that company, and we were stationed west of Bat Doeng. Later on, when the forces from the southwest arrived, they formed a regiment to be based at the south of Basit Mountain. Later on, we moved around to … villages. … The duty of the unit was mainly to follow and monitor the enemy situation.

The witness added that there were about 30 soldiers in a platoon and about 10 in each squad. “The structure of the military is always multiplied by three,” he explained

Witness’s Knowledge of Pol Pot, Son Sen, and Nuon Chea

Mr. Arun asked the witness if he knew what Pol Pot’s role was at the time that he made an announcement at the Olympic Stadium regarding the formation of Division 801. Mr. Ren responded that prior to this announcement, he had never seen Pol Pot and had only heard of Pol Pot through Son Sen. He continued, “While I was at the Olympic Stadium, then I saw him. Before that, I did not know who Pol Pot was. So I concluded that he could have been the Party secretary or the secretary of the Center.”

Asked to clarify what he meant about Mr. Sen mentioning Pol Pot, Mr. Ren said that he heard of Pol Pot’s name through Mr. Sen and also through 06.[35] The witness reiterated, at the defense counsel’s request, that he learned who Mr. Sen was when he convened a meeting at Damnak Snak railway station. At the time, the witness said, “I understood that [Mr. Sen] must have been a senior leader” since he was able to give orders to the witness’s commander and 06. He therefore must have been, in the witness’s mind, “within the leadership rank.” However, the witness did not know Mr. Sen’s precise rank,and denied this repeatedly under sustained questioning from the defense.

Mr. Arun turned to probe the witness on his earlier testimony that at the meeting at the Olympic Stadium announcing the formation of Division 801, the witness had said the meeting was attended by Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, and Son Sen. He asked Mr. Ren whether he knew the ranks of the three other than Pol Pot. The witness said he was not clear as to the relative seniority of these people, although he knew that “Pol Pot was number one; Nuon Chea was number two.” Mr. Arun queried how the witness figured this out. Mr. Ren explained “They referred to the names of the senior people. Pol Pot was known as ‘Brother Number One’ and Nuon Chea was known as ‘Brother Number Two,’ and everyone knew that. That’s all I knew. And of course, if a person was known as ‘number one,’ that person was in the most senior position.”

The defense counsel noted that the witness had frequently testified to the OCP as having received orders from Mr. Sen. He asked whether Mr. Sen had to be in the military to render orders such as those relating to the liberation of Phnom Penh. Mr. Ren responded that before the liberation of Phnom Penh, “reports had to be filed to Son Sen”; “military issues” also had to be reported to Mr. Sen when Division 801 was formed and while it operated in Ratanak Kiri, while political affairs matters would be reported to Pol Pot. Thus, Mr. Ren had concluded at the time that Mr. Sen was in charge of military issues and Pol Pot in charge of political issues, this being a situation he had “learned from my commander.”

Regarding whether he ever had occasion to write reports to both his commander and Mr. Sen. Mr. Ren explained that as the commander of the regiment, he did not have the authority to bypass the commander of the division. “But in some special circumstances,” he said, “when the commander of the division was absent and the situation had to be reported urgently, we would be allowed to do so. But this was a very rare occasion.” He concluded, “If the committee members of the division were all present, we had no excuse to go all the way to the top without notifying them.”

To whom did “all the way to the top” refer? Mr. Arun inquired. Mr. Ren reiterated that issues regarding the border had to be reported to Mr. Sen, while security issues would be reported to Pol Pot. This prompted Mr. Arun to ask the witness whether he ever reported directly to either Mr. Sen or Pol Pot. The witness denied this. He explained, when pressed, “Unless I was granted proxy to gather forces, I would not be allowed to do that or to make any decisions at all.”

Mr. Arun clarified that his question had intended to focus on reporting lines and that he was trying to find out whether the witness reported to his commander and Mr. Sen and whether the Zone Secretary had to be informed. Mr. Ren answered:

I was under the supervision of the division. Whatever happened, it was my duty to report to the commander of the division. Whether the commander had to report to the head of the zone was out of my knowledge. … Without permission, I would not be able to meet any person in the area or to move about freely. For example, when we had to deploy our forces to a location, we had to be given authority to contact local people and people who managed the area.

Returning to the question of Mr. Sen’s role, the witness again testified that he did not know what it was, apart from knowing that Mr. Sen was a “senior leader.”

The defense counsel asked whether the witness ever received direct orders from Pol Pot to attack Phnom Penh. The witness denied this and reiterated that he only received orders from Mr. Sen. In addition, he asserted, his commander “never mentioned that he had met any other individuals other than Son Sen. Son Sen was the only person who was quite familiar to us whenever there was an attack.”

Khmer Rouge Security Centers and Further Discussion of the People’s Representative Assembly

At this juncture, Mr. Arun asked whether the witness was ever aware of the existence of security centers near where he was located. Mr. Ren explained:

First, we did not know whether there were such security offices, because I was far from the division. I am still convinced that I don’t think there was such a security center. But when I moved to Banlung district,[36] after staying there for a short period of time, I started to realize that such centers were in place, because people kept complaining about being arrested and detained in these centers. We also learned from the detainees who escaped. By that, I can confirm that there were such security centers, although I do not know where such security centers may have been located. …

On one occasion, I met a commander on the road. He talked about complaints lodged by the people that they did not do any wrongdoing. They said they just stole some potatoes and with that they were detained at O Kanseng security center. … With that, I discussed to have these people released. Twenty people were ultimately released. So, with that, I can say that there were such security centers under the supervision of Division 801.

For his final question, Mr. Arun asked the witness if he was aware of the identity of the president of the People’s Representative Assembly. The witness denied this.

Clarification of the Witness’s Experiences during the Liberation of Phnom Penh

Taking over from his colleague, Victor Koppe made his courtroom debut in the evidentiary hearings of Case 002/1, asking the witness when he first reached Phnom Penh. Mr. Ren responded that they reached Phnom Penh through the passageway passing Tang Krosaing and Pochentong, but he could not recall the “exact date” on which they arrived.

Mr. Koppe asked Mr. Ren the location of Taing Krasaing hospital, where the witness had been hospitalized. The witness said it was “close to Taing Krasaing pagoda near the railway tracks.” The witness could not quite recall its relative location but could say that “it was already closer to Pochentong area.” Providing further detail of events at this time, Mr. Ren explained:

When I was wounded, during that time, the fierce fighting was on. We advanced toward Pochentong, and I had to be admitted to hospital. But at the same time, my men kept moving toward Phnom Penh. Half an hour later, I heard that Phnom Penh was liberated. … Then I saw people moving out of the city. …

A short time later, when I met the evacuees, I made a short call to Soeun at the brigade and I asked him what happened to the people and he said that they had to be evacuated. I asked him where he was, and he said that he was at Sat Sot Sokon’s[37] house. At the time, we recommended one another to remain where we were for the time being, while the people were being evacuated.

The defense counsel queried whether the witness discussed the evacuation with his men. The witness said, “I did not know or engage in [the evacuation], but again, without any proper plan, such an evacuation could not have taken place.”

Mr. Koppe asked the witness whether he had heard, at that time, any stated reasons for the evacuation. The witness denied hearing anything about this at the beginning, although when he later asked Soeun, he learned that “the commander of the division rendered the order for such evacuation because they were afraid that there would be enemies embedded among the population and that people could hide among themselves, and also, they were afraid that Americans could bomb the city.” He concluded, “And then I learned that the whole population of the city was evacuated to the countryside.”

When asked about his regiment, Mr. Ren explained that they were stationed in the vicinity of Lok Song hospital, tasked with “covering a stretch of road from that hospital to the house that I mentioned the commander of the brigade was taking refuge at.” He explained, “It was the order from the upper echelon that only one battalion could remain to deal with some incidents, for example, some issues that could have occurred from some pockets of enemies … after one week, everyone was asked to move right to the heart of the city.”

The witness continued, “The unit deployed in Phnom Penh had to patrol the area, and they had to remain in the area. They were not allowed to trespass this confined location.” He further noted that other units had been deployed to be “ready to attack if need be. They would be deployed in the areas surrounding Phnom Penh. There were layers of military personnel who were deployed to defend Phnom Penh at that time. “

Regarding what would happen if a member of Mr. Ren’s unit would accidentally cross the boundary of where they were supposed to remain, the witness said, “We had no problem talking to one another or moving about within the vicinity we controlled by nightfall. Every man of the regiment had to gather and was not allowed to walk freely at night. But during the daytime, they could do so.” At this point, the president adjourned the hearings for the lunch break.

American Aerial Bombing Campaign in Cambodia

After the lunch break, a new audience of over 100 students from the Economic and Finance Institute in Phnom Penh took their seats in the public gallery. At the start of the session, the floor was again given to Mr. Koppe, who began a new line of questioning. Referring to the witness’s mention of American bombings as one of the possible reasons for the evacuation of Phnom Penh, the defense counsel asked what the witness had meant by this. Mr. Ren explained, “I asked the people inside [Phnom Penh] the reasons for the evacuation of the people. Through those people, I was told that the evacuation was to avoid the enemies remaining in the city and second, to avoid the aerial bombardment. And of course, the aerial bombardment would refer to the American bombardment.”

Mr. Koppe asked whether the witness had himself ever experienced such bombings. “Of course … a number of times,” Mr. Ren replied. “For instance, when we were along [National] Road 6 and at various [locations in] the countryside, we were bombarded by American planes.” Asked to elaborate, the witness said:

While we were at the front, the plane would just fly over us and sometimes dropped bombs. Sometimes, we had to flee from the trench. Once the plane left, then we returned to the trench. In some other cases — for instance along Road 26 — the trenches there were heavily bombarded. … I cannot recall the year clearly, but it happened before the attack on Phnom Penh. It only stopped when we advanced almost to the outskirts of Phnom Penh. They usually bombarded us when they noticed [we were] soldiers. But when we advanced towards the Pochentong area, the bombardment stopped.

Continuing with this theme, the defense counsel asked the witness whether he also experienced such bombardments before joining the Khmer Rouge army. The witness denied this. This prompted Mr. Koppe to inquire whether the witness heard any accounts from his family regarding their experiences, if any, with American bombardments. Mr. Ren denied this.

What about the possibility of US bombings in 1975? Mr. Koppe asked for his final question, querying whether the regiment made any special preparations in respect of them. The witness responded, “Before or after the liberation, [my military unit] did not prepare any activity or equipment targeting the planes. We did not have such facilities.” He continued, “If we were to be bombarded by the aerial bombardment, then we had to flee the location. We did not have any guns or equipment to fire at the planes.”

Investigating the Investigations: Questions on Witness’s Interviews with the OCIJ

National Co-Counsel for Ieng Sary Ang Udom took the floor next. He noted that the witness had testified yesterday to making three statements to the OCIJ. He asked whether Mr. Ren stood by this statement. Mr. Ren said that he made several statements and could not recall them all, “but it is likely that I was interviewed on three occasions, or at the most, four occasions.”

Pressing the point with a furrowed brow, Mr. Udom asked whether this meant that the witness was not sure how many times he was interviewed. There was a long pause from the witness, with the president eventually interjecting and directing the witness to respond to the question. However, the defense counsel instead rephrased his question, asking the witness how many written records of his interviews he received to review before he began testifying. The witness said that he “had been given several documents” and also brought along some documents himself, so he was unsure. He then advised that he had been given 10 documents but was unsure, because they were “taken back at the conclusion of the proceeding.”

Mr. Udom noted that there were four written records of interview on the case file, which were dated September 17, 2009; October 23 and 26, 2009; and March 9, 2010. He asked if the witness would now acknowledge four interviews having taken place. Mr. Ren said that he recalled only three, but if four records were found, he intoned, seemingly exasperated, “then there were four.”

Furrowing his brow still further, Mr. Udom asked the witness whether he met with OCIJ investigators before the first interview. Mr. Ren agreed that he met them the day before the interview. On that day, he said, “the investigators took some notes.” Was there any recording of such an “unofficial interview”? Mr. Udom asked. The witness said that he recalled a team of approximately four people, with an audio-recording being made.

Mr. Udom clarified that he was not referring to the “official” interview but the preliminary meeting, asking how long it lasted. However, before the witness or Mr. Udom could continue, the president advised them to wait while he gathered again in conference with his colleagues on the bench. After a short conference with all colleagues, the president continued conferring with Judges Silvia Cartwright and You Ottara.

The president then instructed Mr. Ren not to answer this question as it was “irrelevant.” Mr. Udom protested that his role was also to “find justice.” The president retorted that the Chamber had “discretion to rule on matters which are not relevant” to the ascertainment of the truth. After a pregnant pause, Mr. Udom agreed to proceed to another question as he had been prevented from putting to the witness his intended line of questions.

OCP and Ieng Sary Defense Team Clash over Requested Transcripts of Audiotapes

Reluctantly moving on, Mr. Udom noted that in the witness’s first interview with the OCIJ, he had testified about seeing a telegram marked Office 870.[38] Asked whether he indeed said this, Mr. Ren agreed that he did and recalled that this telegram had been handwritten. Mr. Udom advised the court that he had requested the transcript of this portion of the interview audiotape[39] and now sought to have it played. This request elicited a, objection from Mr. Lysak, who suggested that there was no need to undertake this exercise as the transcript had been posted, and the interviewer had been recorded as saying to the witness, “Do you know who signed the message?” with the witness responding, “No, it was just put down as 870.”

Mr. Udom said that something appeared to be amiss, because he, the requester, did not have a copy of this transcript while the OCP appeared to have it. If he had the transcript, he explained, he might not have requested to play back the audiotape. Despite Mr. Lysak standing and signaling an intention to reply, the Trial Chamber judges again huddled in conference, prompting Mr. Lysak to abandon his attempt to interject.

After a few moments, the president advised that Mr. Udom’s request was rejected as it was “not necessarily relevant as now we have the witness before us” and could put questions on this issue directly to the witness.

Thanking the president, Mr. Udom nevertheless protested that this practice had been undertaken before. However, the president qualified that this was a different issue. Seeing Mr. Lysak standing, the president advised the prosecutor that if he wanted to address the same issue, this would not be permitted as a ruling had already been made. Nevertheless, Mr. Lysak persisted and said he wished to clarify that the OCP did not have secret access to the document and it had been circulated to the parties at 3:53 p.m. on January 9, 2013. The president reiterated this fact, after which Mr. Udom said that he learned over the lunch break that there had been a coding error with the document, which was why he had not been properly notified of it.

Moving on, Mr. Udom asked the witness to clarify his testimony asserting that Brother 89 was Son Sen. Mr. Ren said that he had tried to testify carefully and initially did not recall this code name but did recall this after reading the statement of Thin.

Questions on Witness’s Understanding of the Central Committee

Mr. Udom sought to refer to the witness’s testimony in another of the written interview records,[40]noting that he had not prepared a copy for the witness as he thought the witness had them already. He was cut off in asking his question, however, because Mr. Lysak was standing. Given the floor, Mr. Lysak advised that the witness did not have a copy of the written record but should, noting that the OCP had such a copy and would be happy for it to be provided to the witness. The president agreed and ordered for the OCP’s copy to be provided to the witness.

Mr. Udom advised that his question concerned the witness’s testimony in which he said that Committee 870 was the Central Committee and was considered the central leadership. Mr. Udom asked what the difference was between Committee 870 and the Central Committee. Mr. Ren responded, “Office 870 was an office, and another [entity] was the 870 Committee.” The defense counsel asked if these two entities were one and the same. The witness denied this and explained that “Office 870 was under the direction of the Central Committee.”

What, therefore, made the witness say that Office 870 could have been under the senior leaders? Who were the senior leaders? Mr. Udom asked. The witness responded:

In the Central Committee, as I stated, what I knew was that Pol Pot was the first member, followed by Nuon Chea. These are the two individuals that I knew belonged to the committee. I don’t know other people. I don’t know whether Mr. Ieng Sary or Khieu Samphan could have belonged to the Central Committee or not. When two or three people combined, they could make up a committee, a Central Committee comprised of Pol Pot, Nuon Chea – and I just don’t know whether other people could be a part of the Central Committee.

Next, the defense counsel said, the witness had testified to the OCIJ that issues concerning discipline “had to go to Office 870” and that the high-ranking people “generally discussed the emerging problems and then made a decision.”[41] Mr. Udom asked how the witness knew this. Mr. Ren responded:

I did say that during the interview; I wish to now reiterate that personally. I said this because I observed what could have happened back then because the decision had to be jointly made. Committee 870 comprised of a few other people, not just two people, and I believed that these people on Committee 870 could have met to discuss things before they made a decision.

The witness denied being allowed to discuss such things, but “experience tells me that decisions had to be collectively made. An individual person could not make a decision. This applied to 870 as well.” Mr. Udom asked whether the witness ever attended or was informed about the content of the meetings. Mr. Ren replied, “As I mentioned, I worked at a lower level and I was not informed by any member of the meetings of the committee.” He asserted, “I just read the message that had already been written or signed by members of the committee, and I was not personally or directly informed by any of those uncles.”

The defense counsel asked whether it was fair to say that generally, the witness’s testimony on matters that the Central Committee allegedly discussed was “pure speculation.” The witness agreed this was so.

Revisiting Witness’s Testimony on Meeting Announcing Formation of Division 801

In the same written record of interview, Mr. Udom noted, the witness had testified about the merger of Brigade 14 with another group to become 801, and the announcement on this merger at a meeting in Phnom Penh about 15 days after the liberation.[42] Mr. Udom queried whether the witness still stood by his testimony concerning the date on which the meeting was held. Specifically, he queried whether the witness referred to the 15th or 15 days after the liberation of Phnom Penh. The witness said that he stood by his statement.

Mr. Udom noted the witness had said the meeting had been attended by Pol Pot, Mr. Chea, Mr. Sary, and Mr. Sen as the “senior leaders.” The defense counsel queried whether they were all of the senior leaders, to which Mr. Ren replied that he had already clarified in his statement that these were the people who had attended the meeting. This prompted Mr. Udom to ask how the witness could identify the leaders. The witness replied:

I said what I knew, and besides that, I did not know anything else. … I only knew about those people. For instance – Mr. Khieu Samphan – I never knew him, nor Ieng Sary. … I only saw him at that meeting and then I knew that they were senior leaders. Later on, they referred to him as Brother Ieng Sary and I knew him as one of the senior leaders. As for Son Sen, I knew him better.

Noting the witness had testified that Som, the emcee, had announced the leaders,[43] Mr. Udom asked whether Mr. Sary had been introduced as “Ieng Sary” or “Comrade Ieng Sary.” Mr. Ren said that they used the term “Brother,” referring to him as “Brother Ieng Sary.”

Finally, the defense counsel noted that, on the same page of the record of the witness’s OCIJ interview, Mr. Ren had testified to meeting the leaders before the fall of Phnom Penh and then, in response to the next question from OCIJ, that he had in fact met only Mr. Sen and not the others. He asked the witness how he could account for the discrepancies in his statement. Mr. Ren said, “I only met Son Sen, and I did not meet any other leaders. Only after the fall of Phnom Penh [did] I meet them, that is, during the announcement of Division 801. I did not know any of them prior to the fall of Phnom Penh except Son Sen.”

Ieng Sary Defense Team Re-Requests Transcription of Audiotape

At this point, International Co-Counsel for Ieng Sary Michael Karnavas said that he had one clarification and one request. First, he noted that his team had requested a transcription of the audiotape but that the OCP had misled the Trial Chamber in suggesting that this was the document that had been posted on the case file. This posted portion, he asserted, was not the same portion that his team had requested be transcribed. Instead, Mr. Karnavas continued, his team had requested the transcription of the notes that the OCIJ took “during the unrecorded session they held with the gentlemen” and then produce the relevant audiotape. This went to sources of knowledge, he argued; if Mr. Ren provided answers at that time, this was information that his team could not have known before this time.

Mr. Lysak responded, “The only misleading that has been going on here has been from the Ieng Sary Defense Team.” The OCP had not requested any part of an audiotape to be transcribed, so it was most likely a defense team, he asserted. For the defense counsel to suggest that the tape indicated that a telegram did not come from 870 but a transcript did say that, that was misleading, Mr. Lysakopined.

Mr. Karnavas explained that there were two different portions of the tape, asserting that Mr. Lysak had referred to the portion of the interview transcribed and put on the file. What his team wished to discuss was the portion that had not been transcribed, he continued, arguing that this matter required clarification.

This debate prompted a brief conference between the Trial Chamber judges. Upon resuming their seats, the president advised that the Chamber would adjourn for the mid-afternoon break, although a slightly longer one than usual.

Reconvening after a 45-minute break, the president advised Mr. Karnavas, in response to his request:

We already ruled on this matter, but then you requested clarification on the reasons for our ruling. Our reason is based on our decision dated December 7, 2012, that is the decision on the request by the defense teams regarding the irregularities as alleged existed during the investigation.[44] Please refer to the reasons in these decisions, particularly paragraph 22 of these decisions. These are the decisions that the Chamber made on such subject matter, that is, during the proceedings in this case.

Mr. Karnavas began to speak but noted he was being told to wait, and thus did so. The Trial Chamber judges conferred again, with Judge Lavergne gesturing animatedly and leaning in to explain things to his colleagues. The president then further advised that this decision was in response to all the requests Mr. Karnavas made before the adjournment.

To ensure matters were clear, Mr. Karnavas explained that what Mr. Udom was trying to say was that the Ieng Sary Defense Team was seeking to have a section of an audiotape transcribed. Regarding the ruling, however, it was a different matter with a different witness, he said. In addition, he noted, whenever a witness appeared to “have been primed before going on tape,” they would request the transcript of the audiotape, since “sunshine was the best disinfectant for the truth.” The president advised Mr. Karnavas to abide by the Chamber and to appeal the decision if he did not like it.

Witness’s Position in Division 801 and the Pardoning of 20 Potato Thieves

The president gave the floor to the Khieu Samphan Defense Team. Mr. Sam Onn duly began his questions, first asking the witness when he started working for Regiment 82. Mr. Ren said, “It was from the announcement of Division 801.” Mr. Sam Onn asked whether the witness was sent to his destination immediately. The witness said Regiment 82 was stationed “from the west of the stadium” to a pagoda, and then near Poun Phnom pagoda. He was then assigned to Ven Sai, he said, and stayed there for two years before being sent for a study session in Phnom Penh. Mr. Ren added that while “there was no official written letter,” he was assigned to take over from 06, who had been the deputy commander of Division 801. However, he recounted, he “stayed there for only one month” and then went to Phnom Penh, where he got sick.

The defense counsel noted that at 3:31 p.m. in the witness’s testimony on January 9, 2013, the witness had referred to Boeung Kanseng. He also noted the witness referred to O Kanseng. The witness said that these were “two separate names, [and] there was no security center at Boeung Kanseng.”

Returning, as requested, to the episode concerning the people who had been sent to a security center for stealing potatoes, the witness recalled:

I was in that division replacing 06 for a brief time only. I did not even know that there was a division security center at all. … When I was on my motorbike, I was called to return. Four or five days later, people came to meet me, talking about their children. … They told me that their children had been arrested and placed at the O Kanseng security center. Those people also told me that the people that had been detained there actually broke out of the prison and killed the guard.

Mr. Sam Onn asked whether Mr. Ren’s decision had anything to do with the upper echelon. The witness said that when Mr. Sarun came to see him, they discussed the matter between them, during which “I made my request to him, and he said that he would go to [Ven Sai] first.” Mr. Ren explained, “During this two or three day period, I did not know whether he made a further request to the upper echelon or not. What I saw was that a few days later … those people were released.”

Asked who was above Division 801, the witness said that this was Office 870. As for Son Sen’s military section, the witness said that both Mr. Sen and Pol Pot were the upper level. When pressed, the witness described, “First, on the military side, there was Son Sen who was in charge. … Above Son Sen, I would say there would be Pol Pot and no one else. That is the chain of command based on my understanding.”

Examining Witness’s Chronology of Events around the Liberation of Phnom Penh

International Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Arthur Vercken took the floor after his colleague and asked the witness how many times he was wounded during the liberation of Phnom Penh. The witness said he was wounded on the day of the liberation and had been “wounded by a bullet on my thigh.” He remained there, he repeated, for about 17 days while his regiment was sent onwards.

The witness eventually rejoined his unit, he recalled; they were still in their brigade then, but had already been “told that we would be sent further.” These discussions “took place while I was wounded.” Mr. Vercken asked where the witness was at the time these discussions took place. At that time, they were at Poun Phnom, he said, and his deputy came to meet him at the hospital. Mr. Ren confirmed, however, that he had already left the hospital by the time the rally announcing the establishment of Division 801 occurred. He also clarified that he was able to stay in the hospital while the arrangements were being made, because a person could come to speak with him and there was transportation available to take him to meetings if need be.

At this point, Mr. Vercken advised, when asked by the president, that he would require another 40 minutes or so for his questions. The Trial Chamber judges considered this briefly, and then President Nonn advised that the hearing was adjourned for the day. However, before the judges left the Chamber, they huddled in conference again to discuss another issue, with Judge Cartwright gesturing with her hands as if to emphasize certain points.

A Cryptic Conclusion to the Day

The president then took the opportunity to inform the parties that during the hearing on January 11, 2013, the Chamber would discuss the request by the Lead Co-Lawyers for the civil parties concerning a civil party, TCCP 94. He then gestured to Judge Cartwright, who offered a somewhat cryptic message, stating that, to clarify the matter in English, the parties could expect a message from the Trial Chamber this evening making clear the subject matter that the Chamber would wish to discuss concerning that civil party at the January 11, 2013, hearing.

Before the close of proceedings, the president also advised that on that day, Mr. Sary was to be brought to his holding cell to follow the proceedings from there.

Hearings will continue at 9 a.m. on Friday, December 11, 2012, with the continued testimony of Mr. Ren, followed by the testimony of a new witness.