Military Structures, Security Centers, and Internal Purges in the Spotlight

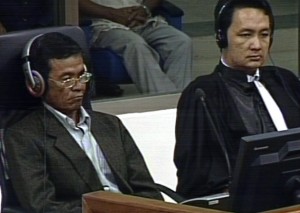

Witness Chhaom Se, accompanied by duty counsel, Lim Bunheng, testifies before the Trial Chamber at the ECCC on Friday.

The former head of a Khmer Rouge security center took the stand in the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Friday, January 11, 2013. Under questioning from the prosecution, the witness, Chhaom Se, provided in-depth insight into Khmer Rouge military authority structures, communication, and internal purges. He also offered testimony on the evacuation of Phnom Penh and other provincial towns and early operations of the Khmer Rouge military. Aspects of Mr. Se’s testimony echoed that of witness Ong Ren, a Khmer Rouge army regiment commander who was from the same division as Mr. Se and concluded his testimony earlier in the day.

During the hearing, the Trial Chamber also decided to defer its decision on whether to hear testimony from a civil party based outside Cambodia, after hearing a quick, hotly-contested debate between the parties as to the appropriateness of calling this civil party. This witness reportedly would be able to testify, in particular, as to the roles of accused persons Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary, although defense teams contested that her testimony had little relevance to the particular scope of Case 002/1.

Ruling on Participation of Nuon Chea from Holding Cell

Over 250 students from Techo High School in Angtasom, Takeo province, attended the hearing this morning, witnessing Trial Chamber Greffier Se Kolvuthy start the day’s proceedings with a brief report advising that all parties to the proceedings were present, except National Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Kong Sam Onn and International Lead Co-Lawyer for the civil parties Elisabeth Simonneau Fort (who would appear later in the day). In addition, accused persons Ieng Sary and Nuon Chea were both once again participating in the hearing from their holding cells due to health reasons.

Elaborating on the health condition of Mr. Chea, Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn advised that the Chamber had this morning received a medical report from the ECCC detention facility’s treating physician. Noting that Mr. Chea had problems with his health, the doctor recommended that Mr. Chea participate in the proceedings from his holding cell. In order to “avoid substantial delay to the proceedings, in the interests of justice and according to the medical report,” the president duly ordered Mr. Chea’s participation to be from the holding cell for the day.

Yet Another Revisiting of Witness’s Testimony on Olympic Stadium Ceremony Establishing Division 801

After this announcement, International Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Arthur Vercken resumed his questioning of witness Ong Ren,[2] a former Khmer Rouge army regiment commander. Directing Mr. Ren back to their discussion at the hearing on January 10, 2013, concerning the witness’s attendance at the Olympic Stadium ceremony regarding the establishment of Division 801, Mr. Vercken explained that he wanted to know whether, at that time, the witness was still in the hospital or had already been discharged to rejoin his men. Mr. Ren indicated that he had, in fact, already been discharged.

This answer prompted Mr. Vercken to inquire as to the particulars of dates, namely the lapse of time between Mr. Ren’s discharge from the hospital and the ceremony. Mr. Ren said that while he could not recall precisely, the ceremony took place “quite a while” after his discharge from the hospital.

The audience at the Olympic Stadium consisted of “division forces,” Mr. Ren testified. Mr. Vercken noted that neither in the witness’s October 23, 2009, statement to the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (OCIJ) nor in the transcript of that interview[3] did the witness include Khieu Samphan as one of the leaders who he recalled had attended this ceremony. The defense counsel asked whether the witness confirmed that Mr. Samphan was not, indeed, in attendance. Mr. Ren agreed with this, explaining, “I myself never knew [Mr. Samphan]. Even when I arrived in Phnom Penh, I still did not know him.” Mr. Vercken asked whether the speakers at the ceremony were introduced. Mr. Ren agreed that the emcee did this.

The purpose of the ceremony was “the integration of Division 11 and for the assignment of the new division to Ratanak Kiri province,” Mr. Ren explained, when asked. After the ceremony, “the soldiers still remained in Phnom Penh,” but others[4] went ahead to Ratanak Kiri “to prepare the ground for them” 15 days after the ceremony. The soldiers followed “when the water [level] in the river was still high,” which the witness estimated was in about October 1975. Their journey took them to Kratie “in around late November,” where they remained for “three or four days” to rest, he continued; they moved on to Stung Treng “probably on December 15” before eventually making their way along the final leg of the journey to Ratanak Kiri. Thus, the witness confirmed, their journey took them a very long time.

Mr. Vercken asked the witness whether several ceremonies regarding the establishment of Division 801were held at the Olympic Stadium. Mr. Ren advised that he attended three such ceremonies. When pressed, he explained that the first regarded the organization of Division 801; the second called together representatives from districts, zones and regiments across the country; and he could not recall the particulars of the third.

The witness then explained that the “study session,” which, it would become apparent, was a reference to the second Olympic Stadium meeting, concerned “the victory of April 17,” in particular, “the meaning of that victory and the future directions that we needed to follow.” Mr. Ren further explained that the “two core duties” of the army were also described, namely that first, the army was to “defend the country, in particular, along the borders with neighboring countries and at the designated spearheads,” and second, the army needed “to be vigilant in solving the livelihood problem in each respective division.” The witness concluded, “I received instruction in the first study session on these topics, and when I returned to Siem Pang,[5] I tried hard to implement these instructions, to engage in rice farming.”

There was then an exchange between the defense counsel and the witness to try and understand each other, with Mr. Vercken explaining that he wanted to know whether all three ceremonies concerned the organization of Division 801. Mr. Ren stated that all three were held in 1975 and that two of the ceremonies had nothing to do with the establishment of Division 801. He further clarified that the ceremony he attended at the Olympic Stadium concerning the establishment of Division 801 was the only occasion on which this announcement was made.

Witness’s Military Training

Mr. Vercken raised a subject that had not yet been touched upon in the witness’s testimony in the ECCC, namely the nature of his military training. Mr. Ren explained that, in fact:

From the day I joined the army, I never attended any military training or school. I joined the army and learned on the job. I learned from running from the bullets when, for example, gunshots were heard. We would, [at such times,] take refuge in bunkers or hide behind trees or stumps. This is what I learned about becoming a soldier during the Democratic Kampuchea. We never attended any formal military training.

Asked about whether the cadres were also subject to the same kind of training, Mr. Ren implied that this was so, answering, “At that time, there was no school for military training.” He highlighted that the commander of his division “told us that we did not need to be trained, because by learning on the job, we would learn already how to become a soldier.”

Mr. Vercken directed the witness to his earlier testimony regarding his ties with the upper echelon and his communication with them via telegram or by walking for five days to deliver them a message when there were no batteries. He sought clarification as to which of the two methods was prevalent. Mr. Ren replied, “The battery was not easy to obtain. We used a small device that consumed the battery. The battery would run out very easily or quickly after one or two days.” After this, they had to walk, he said. In such a situation, Mr. Vercken inquired, was it fair to say that the witness was very often forced to make decisions independently in such situations? Mr. Ren disagreed with the characterization but conceded that he did make decisions independently on occasion.

Noting that the witness was close to the border during the time of Democratic Kampuchea (DK), Mr. Vercken asked the witness to assess the relative adequacy of his equipment relative to other units at that time. Mr. Ren advised that his unit’s supplies were sufficient to allow them to resist attacks for three days before calling for backup. On this point, Mr. Vercken asked whether this situation of autonomy was characteristic of other units along the border.

This inquiry provoked an objection from International Assistant Co-Prosecutor Dale Lysak. He argued that it was inappropriate to characterize this situation as one of “autonomy.” Mr. Vercken said he did not intend to suggest this and could perhaps characterize it instead as the ability for units to function “on their own.”

The defense counsel then addressed the witness with what would be the final question put to him in his testimony before the ECCC, explaining that what he had wanted was for the witness to compare the situation of his unit in terms of the quantity and quality of equipment against the situation of other units. “Our division was similarly equipped as other divisions,” Mr. Ren replied. “However, the convenience for others was different from us. We faced some [unique] difficulties because we did not really have road access close to the position where we were posted,” which was not the situation for other units.

On this note, the president dismissed the witness, thanking him for his testimony.

Debate Concerning the Possible Hearing of a Civil Party

Moving on, President Nonn advised that, as the Chamber had foreshadowed on January 10, 2013, and by a subsequent email, it was still considering whether it should hear the testimony of TCCP 94. He invited five-minute discussions from each party on this matter, ceding the floor first to the Lead Co-Lawyers for the civil parties since they requested this civil party be heard.

National co-lawyer for the civil parties Sam Sokon advised that the civil parties wished to have this civil party testify on the roles of the accused, the situation at Boeung Trabek, and Khmer Rouge policies concerning returnees from abroad. The civil party’s testimony was relevant, he argued, as the civil party’s whole family had suffered during the evacuation, and in addition, the civil party knew clearly about the roles of Mr. Sary and Mr. Samphan, particularly as she attended a session with these co-accused and returnees from abroad. She could also testify as to Khmer Rouge policies with respect to the evacuation, he concluded.

Continuing on from Mr. Sokon’s discussion, international co-lawyer for the civil parties Beini Ye took the floor, advising, first, that she was speaking on behalf of the civil party lawyer Nushin Sarkarati, who could not be here today. Ms. Ye first sought to address the issue of a Voice of America (VOA) interview that was not on the case file but was publicly accessible. She advised that only the Office of the Co-Prosecutors (OCP) had an obligation to notify the Chamber as to publicly accessible documents. In addition, not only was the interview referenced in the witness’s initial application and therefore known “all along,” VOA would post a version of the interview in two languages on its website next week, she said. Moreover, while the civil party lawyers would not use transcripts of the interview in their questioning, the civil party lawyers would not object to other members doing so.

Finally, Ms. Ye said, the civil party would not testify on the roles of the accused during her statement of suffering. She said that this would enable all parties to pose questions to the civil party. Thus, she concluded, there was no need to be concerned.[6]

International Assistant Co-Prosecutor Dale Lysak advised that while this civil party appeared to be unable to testify extensively as to the evacuation of Phnom Penh, she did appear to be a very useful witness, as she appeared to be able to testify on political education that Khieu Samphan provided and particularly the policy of forced movement of the Vietnamese. Mr. Lysak argued that this, for the OCP, was a “very significant matter” in terms of establishing Mr. Samphan’s knowledge of events. Moreover, he asserted, her prospective testimony seemed likely to be able to help establish Mr. Sary’s authority in relation to policies concerning returnees abroad and his understanding of persecution and purges. If the VOA interview was posted on the website, he concluded, this arguably gave the parties adequate time to prepare, bearing in mind that the civil party would also have to travel.

The first to take the floor from the defense was International Co-Counsel for Nuon Chea Victor Koppe. He suggested that, pursuant to paragraph one of the email from yesterday, this witness did not appear to be particularly relevant for the case at present, although his team would concur with the positions of Mr. Sary and Mr. Samphan’s defense teams since it seemed that this civil party’s testimony could implicate those teams’ clients.

International Co-Counsel for Ieng Sary Michael Karnavas prefaced his comments by saying that his team never wanted to prevent civil parties from coming to testify. However, with respect to this civil party, he asserted, there had been 10 instances where she had been mentioned, dating from February 17, 2011. Confusion had been generated on the OCP and Lead Co-Lawyer’s side, he said, as they had gone back and forth as to whether to hear this party.

“The tripwire” for the Chamber’s current decision, Mr. Karnavas suggested, was paragraph one of its January 10 email, which stated, “[The civil party’s] inclusion in Case 002/001 was mainly on the basis of information that she and her family were directly involved in the evacuation of Phnom Penh.” It seemed that the Trial Chamber would have known what else this civil party could testify about but that, judging by the email, “those other matters were not deemed to be sufficiently important” for this case, since presumably other witnesses would be able to cover those matters.

His team’s position was that “there is absolutely nothing that this [civil party] can offer that has not already been presented to this Court.” She could, he conceded, potentially add to the Chamber’s understanding of the situation of Boeung Trabek. However, if she was going to be called to testify on this subject, he argued that two other civil parties, who were “only down the street from here” — and implicitly suggesting, not overseas like the civil party in question — should also be called, as his team had long argued. In addition, he concluded, if the Chamber did not consider the civil party’s testimony on Boeung Trabek essential, then it could consider “saving international taxpayers some money,” as the team felt that “the information that this civil party could provide is redundant and there is nothing of added value.”

Mr. Vercken added that he was “surprised to hear” that the civil party did not have anything to say about the evacuation of Phnom Penh and instead, the civil party lawyers were trying to justify her appearance by suggesting that the civil party could testify on these other matters. In addition, he added, it was never foreshadowed in the civil party’s application that she had attended an education session conducted by Mr. Samphan at Boeung Trabek. These issues on which the civil party’s potential appearance was being justified did not relate to the facts of the case, and it would arguably be a waste of the Chamber’s time to hear her testimony, he argued. While his team agreed that all people on the witness list should be free to come and testify, he concluded, this had to be on the condition that their testimony had some relevance for the trial.

The president permitted Ms. Ye to respond to defense team comments on the reason for which TCCP 94 had been called. In particular, she noted that in the Trial Chamber’s memorandum dated February 17, 2011,[7] this civil party was listed under Office B-1 Boeung Trabek. Therefore, she argued, it could not be said that this was a surprise and that it was initially proposed for the civil party to be called to testify regarding the first forced transfer.

Mr. Lysak added that there were two “completely incorrect” assertions made by the defense teams. First, he said, the witness’s knowledge of Boeung Trabek was indeed flagged in her civil party application. Second, echoing Ms. Ye, he stated that the civil party had been selected to testify on Boeung Trabek and not on forced movements. In addition, he asserted, he felt that the defense was not conceding the facts on which the civil party could testify. Therefore, it was inappropriate for the defense to suggest that it was unnecessary to hear from this civil party. Finally, he said, Mr. Vercken seemed to leave out that the role of the accused was a significant part of the facts to be considered for Case 002/1.

In response to Mr. Lysak’s comments concerning the contents of the civil party application, Mr. Vercken stated that in the document entitled Victim’s Information Form,[8] Boeung Trabek was indeed not mentioned at all. Neither, added Mr. Karnavas, had it been indicated in the summary.

Thanking the parties for their submissions regarding this matter, the president informed the parties that their opinions would form the basis for a Trial Chamber decision that would be issued “in due course.” He then adjourned the hearing for the mid-morning break.

Interim Ruling on Application Concerning Possible Testimony of TCCP 94

After the break, the president advised that, concerning civil party TCCP 94, its interim ruling was as follows:

The Chamber has already noted the submissions by the parties to the proceeding concerning this. The Chamber therefore defers the summons of this civil party for the time being and in the meantime, the Chamber will consider the relevance of the civil party as opposed to other civil parties before the Chamber. The final decision will be made in due course concerning this matter.

Former Khmer Rouge Soldier Chhaom Se Testifies on Early Military Operations

Following this ruling, a new, bespectacled witness took the stand. Under questioning from the president, he advised that his name was Chhaom Se and he had no aliases. Born on September 15, 1950, the 62-year-old witness said that he was born in Kiri Vong district in Takeo province. He currently lives in Anlong Veng district, Otdar Meanchey province, where he works as a farmer. His wife is On Sopheap, and they have four children.

At this point, the president noted that a duty counsel, Lim Bunheng, was supporting the witness. He apprised Mr. Se of his right not to incriminate himself and advised that the witness could consult with Mr. Bunheng if he was concerned about potentially violating this right by responding to a question. However, the president stated, he was obliged to respond to all other questions for which there were no potential of self-incrimination.

Mr. Se confirmed, when queried, that he had given four interviews to the OCIJ: twice in 2010 and twice in 2011. These interviews took place at the witness’s home. He confirmed that he read all of the interview records but did not recall them all. The president asked the witness whether he was certain that he was indeed interviewed twice in 2011. Mr. Se conceded that he might have been mistaken; the interviews were conducted, in fact, in 2009 and 2010. However, he confirmed the accuracy of the written records of these interviews.

Ceded the floor, Senior Assistant International Co-Prosecutor Chan Dararasmey provided the witness with copies of the written records of his interviews.[9] He noted that according to two of them, the witness testified to joining the revolutionary movement in 1970. Asked why he did so, Mr. Se responded, “I didn’t have any understanding of politics; however [back then], we were influenced by the appeal of the then-Prince Norodom Sihanouk. We were convinced that only by running into the jungle could we … join the revolution.”

At the time, Mr. Se was 20, and, he explained, “we were not yet cooperating with the Vietnamese. We had our own local movement. The movement gained momentum and it evolved over time.” He continued, “Then I moved to Kampong Speu. Then we joined with the Vietnamese in the jungle, and we continued to work shoulder to shoulder all along with the Vietnamese until later years.”

Initially, Mr. Se was a “simple combatant,” he said. However, a year after joining forces with the Vietnamese, a military structure was established and the movement joined forces with military forces in Takeo and Kampong Speu. The military unit “was called Unit 6 and I was engaged with this movement all along.” Mr. Se confirmed that he was “established as the chief, or leader” of a military unit and was tasked with “leading the soldiers to engage in fighting in the battlefields.”

Mr. Dararasmey asked the witness to explain the reason behind the cooperation with the Vietnamese forces. Mr. Se obliged, stating, “Since 1970, the resistance had some joint forces or cooperation with the north Vietnamese troops. This was in place since the beginning. Without such cooperation, the Khmer Rouge forces could never have been gathered.”

Military Structure and Leadership of the Khmer Rouge Army Prior to the Fall of Phnom Penh

Moving on, the prosecutor asked the witness to describe the structure of the unit in which he was situated. Mr. Sen explained, “I know only the military structure in my region. The movement that I engaged in, we had units 110, 120, 140, 160, 170, and 190, the units attached to the Southwest Zone. [They] were established in 1970, 1971, when the forces were [gathered].” Within that structure, the witness recounted, he was located “in the first platoon or the first company, in Battalion 160 in the Southwest Zone, under the command of a Battalion Commander, that is, So Sarun.” Above Mr. Sarun was Chhit Choeun alias [Ta][10] Mok.

Mr. Dararasmey noted that there had been an establishment of a special zone, according to the witness’s OCIJ testimony. Asked about this, Mr. Se explained that while he could not explain the reasons for the establishment of the zone, he could say that this “special zone” had been created from parts of other zones “in order to form the resistance for the protection of the Phnom Penh zone.” This special zone, he continued, was made up of three divisions, surrounding Phnom Penh, with division 12 located to the east, 11 to the south, and 14 to the northwest.

The zone, he said, was under the command of Vorn Vet. Mr. Se explained that he did not know much back then beyond the leadership of Division 11. However, he knew that Mr. Vet was the zone leader as he heard this from Mr. Sarun, his division commander.

Between 1973 and 1975, Mr. Se said, proceeding with the chronology of events, he was “with the same division, that is, Division 11.” “In late 1974,” he continued, “Division 11 … was combined with Division 14 … and in 1975, we started to attack and liberate the city. We actually were part of Division 14 by then.” Mr. Dararasmey asked about the reason for the combination of the two divisions. Mr. Se replied that he believed that this was because “Division 14 lost a substantial number of forces” while Division 11 still had its full complement of soldiers. This prompted the prosecutor to query what actually happened; that is, were the divisions integrated, or did they remain intact, with some forces moved to Division 14? The witness clarified that it was the latter: half of Division 11’s forces were sent to join Division 14 forces at National Road 5, while the other half remained in the south.

Continuing on, Mr. Se recounted, “Later on, the three divisions had their name changed into a new one … after the attack on Phnom Penh and after Phnom Penh was liberated. Division 14 changed to 801, Division 11 changed to 605, and Division 12 changed to 803. They were all in the special military zone.” At this point, Mr. Se became deputy commander of a company that formed part of Division 801.

Mr. Dararasmey asked whether Mr. Se had discretion as the deputy commander to decide on matters. The witness explained, “The authority for me was to manage the soldiers in my own company. There were a little over 100 soldiers in my own company.” Overall, he said, the main commander of the division was Mr. Sarun, and his responsibilities were as follows:

The leadership was a one-man leadership style. So Sarun was in charge of politics and for that, he was the top person in the division. He had the authority to make decisions. At that time, the division was a kind of mobile division in charge of certain targets and directions. After the war ended, it was then assigned to relocate itself to Ratanak Kiri province.

Code names were allegedly used for some soldiers in the division, Mr. Dararasmey said, moving on to a new topic. He asked whether Mr. Sarun had a code number. Echoing earlier testimony from witness Ong Ren, Mr. Se said that it was 05. The prosecutor asked whether Mr. Se knew a person named Ta San and if so, what his role was. Again echoing Mr. Ren, Mr. Se said that Ta San was the deputy commander of Division 801 and his code number was 06.

The Fate of Lon Nol Soldiers and the Fall of Oudong

“Prior to the liberation of Phnom Penh, I was the deputy commander of a company. In Khmer, it was called kong roy, which is company in English,” Mr. Se testified next. He confirmed that his company attacked Lon Nol soldiers “in the west; that is, in the vicinity of Kampong Speu province.” For the attack on Phnom Penh, his soldiers were located to the south and north.

Asked about the fate of captured Lon Nol soldiers, the witness explained, “On the battlefields, of course we had to fight and kill one another. There were no exceptions.” Capture would only occur at the end of a battle. However, he was unaware of the ultimate fate of captured Lon Nol soldiers, as “it was up to the upper echelon to decide the fate of the captured soldiers.”

As for the liberation of Oudong,[11] Mr. Se said, when asked, that his soldiers had not yet arrived in Oudong when the battle took place. They were “along Road 38, that is, at Kampong Tuol, or Kratourt, or Wat Ha.[12] It was at the south line.” He only learned about the liberation of Oudong on a later date. Mr. Dararasmey asked who would have been in charge of the liberation of Oudong. Mr. Se denied any knowledge of this. Neither could Mr. Se recall all the towns that had been liberated before April 1975.

Conditions of the Evacuation of Phnom Penh and Locations around Country

Mr. Dararasmey asked the witness what happened at Kratie, Kampong Speu, and Kampong Cham. The witness stated that this was beyond his knowledge. Pressing on this point, the prosecutor asked whether Mr. Se heard about what was happening across the country prior to the fall of Phnom Penh in 1975. The witness agreed that he did hear some news concerning Takeo and Kampong Speu, explaining:

After [Khmer Rouge soldiers] arrived at each provincial town, then people would be evacuated from the provincial town for a while. That was my observation. They would not allow people to stay at their residence immediately after the liberation for security reasons. That was what I knew … because in each provincial town, there would remain some weapons, and there could be people scattered here or there within the provincial town that could attack some forces or cause harm to the residents. So the order was for the people to evacuate so we could control the situation absolutely, immediately after the liberation.

As to whether townspeople were given any other reasons for the evacuation, Mr. Se advised that “of course” there were other reasons, but he could not recall these. On where people were evacuated, the witness said that people could be evacuated “to this direction or that direction.”

Mr. Dararasmey asked whether people protested the order to leave. The witness explained, “People talked about their houses, about their properties. They did not want to leave. But, based on the commander’s orders, they had to leave.” He continued, “However, they were not threatened or threatened to be shot. We just informed them of the reasons to leave. But as for the loss of property or houses, it was beyond my knowledge. I just implemented the orders.”

In response to a question concerning what happened to people who refused to obey the orders of Khmer Rouge soldiers during the evacuation, Mr. Se said, “I did not see any incidents of people refusing to leave or any shots fired in relation to people who did not leave. The liberated army was of high morale. They did not conduct any vicious attacks towards the people. That was the discipline of the army.”

Regarding the belongings, if any, that evacuees could bring with them, the witness explained, “People were not prohibited from taking anything with them. They could manage to bring anything at all they could carry with them. But they could not take heavy loads, I believe. But they could do their best to bring whatever they could.” As for whether the Khmer Rouge transported evacuees, Mr. Se stated, “No transportation was provided. People [were] on their own. There were no trucks provided for easing the evacuation of the people.”

On whether there was any discrimination against different groups of people at the time, Mr. Se remarked:

I believed that people were treated equally. They were not classified as the enemies. It did not matter whether they lived in the liberated zone or in the area controlled by enemy forces. I don’t know of any policy to discriminate against enemy people, and I don’t know what happened when people returned to their hometown.

Command and Communication Structures

The witness denied, when asked, having any knowledge about the command structure of the Khmer Rouge military. He said that all he knew “was that I received orders from my commander. Whatever orders were rendered down, we had to follow them. That’s all.”

As to the form of communication of orders, the witness advised that he would normally receive orders by radio, and sometimes by messenger. Mr. Dararasmey then expanded his inquiry to means of communication more generally. Mr. Se said, “Communication was not easily or quickly sent to the people concerned because of the constraints in radio communication. It could sometimes be very late before important information could be transmitted. Sometimes it was even too late for the wounded people to be treated and collected.”

During battles, Mr. Se kept in touch with his superiors “through different means. Each small unit or squad, for example, like a squad, platoon or company, had to be on its own. They had to manage their own forces … properly … [so that] the situation was under control.”

Witness’s Attendance at Meetings with Senior Leaders and Study Sessions

Moving on, the prosecutor inquired whether the witness ever attended meetings of senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge after Phnom Penh was liberated. Mr. Se agreed that he did, and described the relevant event he attended as follows:

I attended a conference in which a pronouncement was made publicly concerning the leadership of the Khmer Rouge, and also the anniversary of the establishment of the army at that time. The event was held at the Olympic Stadium, and people from different military divisions and establishments were invited to attend the event. There were people from the company and battalion and so on and so forth. Names of individuals in the leadership were also read out at such conference.

Before the fall of Phnom Penh, however, Mr. Se said that he never attended any meetings of senior Khmer Rouge leaders, although he “did attend some sessions where important people from the divisions were needed to attend.” Mr. Se explained that, at these sessions:

Important documents were handed over to the participants. These documents were meant to educate us on the general situation, certain situations concerning the military, and progress being made [and] also on the building of the resistance movement, how the movement progressed, so on and so forth. The documents were to improve the leadership capacity so that eventually we would liberate the country. There were conditions, there were political issues, lessons on understanding enemies as opposed to friends, and as I stated, it was to ensure that we could win the victory ultimately. …

The building of the forces was to ensure that the country was liberated, and indeed, the resistance would really like these policies and objectives. I did not know the plan behind this, but I believe from the sessions I attended, the intention … was to ensure that people were freed from suffering and the country liberated.

Mr. Dararasmey inquired whether, during those sessions, the witness learned about how to overthrow the enemy government in Phnom Penh. Mr. Se agreed and explained, “We were lectured on how to topple the government of Phnom Penh and to install the ideology we wished to have [in place] afterwards.” Battalion commanders would normally lead these sessions.

The prosecutor inquired whether the witness was also advised about military plans during these sessions. Mr. Se agreed, elaborating, “Normally, as a soldier … we were lectured on the strategic plan to attack … tactical plans, for example … on how to win over these locations.” However, he could not recall the details of these.

Invited to name any participants at these study sessions, the witness explained that he was unable to do this as “there were secretaries of battalions, regiments; some people disappeared, some people came, and I don’t remember them all.”

As for whether the witness ever saw the senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge, such as the co-accused, Mr. Se said, “I knew about Mr. Khieu Samphan, Mr. Nuon Chea. I saw them from a distance. But we were never in contact. I never knew them personally, because in my capacity as a low-ranking soldier, I was not entitled to be close to them, because our titles were too far apart.”

Mr. Dararasmey asked how the witness knew these leaders. Mr. Se said that as he had mentioned, at a meeting at Olympic Stadium, 21 senior leaders attended the event. He did not recall them all but he could recall seeing Pol Pot, Mr. Chea, Chhit Choeun alias Ta Mok — who the witness mentioned “having some contact with in my capacity as a soldier” — Koy Thuon, Touch, Ya, Son Sen, Mr. Sary, Mr. Samphan, Ieng Thirith, Ros Nhim, Kang Chab, Vorn Vet, Chey Suon, and Chong On.

At this point, the prosecutor moved to a new point, questioning the witness about his mention to the OCIJ of a woman named Van. Asked for the identity and role of this woman, Mr. Se said:

I was asked whether I knew the person by the name of Van, as a male, but I said I didn’t, I only knew this person as a woman. This person now lives in Ratanak Kiri province. I don’t know whether she is still alive. … Our units worked together. We had male and female combatants and soldiers who jointly advanced on from the Pochentong location. We reached the propaganda ministry altogether when we were attacking Phnom Penh.

Revisiting Witness’s Knowledge of the Evacuation of Phnom Penh and its Aftermath

The prosecutor inquired as to the conditions of Phnom Penh immediately upon the witness’s arrival there. Mr. Se said, “Phnom Penh was a crowded city. We saw a lot of people on the street. They were mixed with soldiers.” However, he noted, “I did not spend a lot of time in Phnom Penh because immediately we were asked to move out of the city as well, and the population of the city was also asked to leave the city for a certain period of time. We left immediately.”

Mr. Dararasmey asked the witness how long it took to liberate Phnom Penh. Mr. Se replied, “It took us about three months before we could finally liberate Phnom Penh. Fighting was intense, fierce.” Mr. Se denied having any knowledge regarding what happened to Lon Nol soldiers who were captured at that time, as this was the decision of upper levels.

Mr. Dararasmey asked the witness to clarify whether he bore witness to the evacuation of Phnom Penh. Mr. Se responded, confidently, “Yes, I did. I saw people walking on the roads. There were gates where people would be allowed to leave the city.” Mr. Se knew also that there were plans for evacuees after they left Phnom Penh but did not know the details of these plans, as he had left for Ratanak Kiri province. Following this response, the president adjourned the hearing for the lunch break.

Treatment of Lon Nol Soldiers and Details Concerning the Evacuation of Phnom Penh

Following the break, a new audience took their seats in the public gallery, comprised of around another 100 villagers from Takeo province, many of who appeared to have been born before the DK period. Approximately 100 students from the National University of Management in Phnom Penh joined them.

International Senior Assistant Co-Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde took the floor. He first asked the witness about his having attended training sessions with division members and being taught to distinguish between enemies and friends. He asked Mr. Se what the witness was told about who his enemies were before the fall of Phnom Penh. “The enemy was those people working under the Lon Nol regime, and those soldiers — that is, the Lon Nol soldiers — as well,” Mr. Se replied.

Mr. Se confirmed, when asked, that he heard about the “seven super traitors of the Lon Nol regime.” After hearing about this, the witness explained, the front movement was established. Mr. de Wilde queried who issued the communiqué concerning the Lon Nol regime. Mr. Se said that he could not recall but “everyone was well aware of the [seven super traitors] phrase.”

Moving on, the prosecutor asked whether the witness’s division was one of the first to enter Phnom Penh. The witness advised that there were “battalions and regiments based on the assigned directions.” Mr. de Wilde asked the witness more specifically whether his unit entered Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975. Mr. Se agreed this was so.

Mr. de Wilde asked the witness whether he was issued specific orders regarding what he was to do with Lon Nol soldiers they captured. Mr. Se responded, “After Phnom Penh was liberated, I did not have the knowledge of the Lon Nol soldiers, but they were taken from the city to the countryside, [although] I did not know what measures were taken against them.” As to the point in time in which the witness received these orders, Mr. Se said, “I believe that the plan to evacuate the people had been preconceived because based on experience, there had always been plans to evacuate the people after an area had been won, because there could always be [pockets] of fighting in a newly-seized area.”

What were the reasons Mr. Se was given for why they had to evacuate Phnom Penh? Mr. de Wilde queried. The witness said that this was “so that we would be able to take control of the city. … The soldiers from all directions were issued the same orders … in order for us to control the situation.” The witness agreed that they had been told that “pockets” of enemies would still be present. “Remnants of the defeated army” would still be encountered in Phnom Penh “here and there,” he recalled being told.

There were no exceptions to the order that people had to be evacuated, Mr. Se said. Did this, the prosecutor inquired, include “pregnant women, the sick and elderly, [and] handicapped persons?” Mr. Se agreed that it did.

Mr. de Wilde asked whether there were checkpoints established in and around Phnom Penh to filter out Lon Nol soldiers. Mr. Se denied any knowledge of this and explained:

I only knew what happened at my target; I only knew about my company and the nearby companies that worked together with mine. … As for the process regarding the transporting of prisoners of war, this was the responsibility of the division commander. That was within their authority. … I did not have the authority to make that decision.

Post-Evacuation Period and Witness’s Assignment to Ratanak Kiri Province

Moving on to the immediate post-evacuation period, Mr. de Wilde asked the witness what area of Phnom Penh his division was located in after the evacuation. Mr. Se replied that his division was stationed west of Psar Thmei Market,[13] with parts of the division based near the Olympic Market. “My own unit was stationed to protect the Ministry of Propaganda,” he explained, “because there was a concern that there could still be enemies remaining inside, so we had to implement this plan to avoid any possible eruption of war within a few months after the liberation. … We patrolled along the night in the street in the targeted area.”

Mr. de Wilde noted that the witness had described to the OCIJ a time in which his division had been part of the Central army.[14] He asked the witness to elaborate on this episode. Mr. Se obliged, describing how his division attached to the Central army “when we were part of the special zone.” He continued, “As I said earlier, the three divisions were attached to the central zone … and were like mobile divisions. … There were about 12 divisions altogether that belonged to the Central army.”

The prosecutor noted the witness mentioned to the OCIJ that Divisions 502, 450, and 417 had been attached to the Central army.[15] He asked the witness whether he could recall any other names. Mr. Se said that he could not recall this now, only that there were three divisions from the southwest and 12 in total.

The president granted the prosecutor permission to quote an excerpt from one of the written records of the witness’s OCIJ interviews, in which Mr. Se had said, “Division 801 was created in Phnom Penh during the general assembly at the Olympic Stadium in the month of September 1975, approximately. As part of Division 801, I was deputy commander of the company.” The witness had also noted 11 companies being part of the division.[16] Mr. de Wilde asked whether the announcement was made during the Olympic Stadium ceremony that Division 801 was to go to Ratanak Kiri. Denying this, Mr. Se explained, “We were not told in advance. We were in fact told to control the situation in Phnom Penh first for up to four months. Once it was in complete control, then we would be assigned to go [elsewhere].”

Over 1,000 people attended the Olympic Stadium meeting, Mr. Se said in answer to a question from Mr. de Wilde on this point. In the witness’s testimony before the OCIJ, the prosecutor recounted, the witness had testified that Son Sen, Pol Pot, and Mr. Samphan spoke at that ceremony.[17] Did Mr. Chea also attend? Mr. de Wilde asked. Mr. Se agreed that Mr. Chea did attend and made a speech at the ceremony, although he could not recall the contents of that speech. Mr. de Wilde asked if Mr. Se could recall Son Sen’s alias. The witness denied this, explaining that they had not been close.

Khmer Rouge soldiers gather at Olympic Stadium during the Democratic Kampuchea period.

(Source: Documentation Center of Cambodia)

Mr. Se agreed, however, that there was discussion at the Olympic Stadium ceremony of the “enemy within the country” and the “enemy without.” This continued to evolve, he said, as the movement kept growing and people kept being re-educated, so it was based on the situation.

Mr. de Wilde asked whether the witness had ever had the opportunity to read the Revolutionary Flag. Mr. Se said that he did not have the opportunity to do so, as he was in the Youth League. Thus, he was permitted only to read the Youth Flag. The prosecutor requested to read an excerpt from the August 1975 Revolutionary Flag. Under a heading “Long Live the Most Extraordinary Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea (RAK),” the issue described how the head of the Party organized “an important political conference” of all 3,000 members of the units of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) to discuss the successful liberation of Phnom Penh, the history of the RAK, reasons for the victory, and new tasks for the RAK.[18] Was this ceremony that the witness attended at the Olympic Stadium different from the one described, or the same? Mr. de Wilde asked. Mr. Se said he believed these messages were “consistent with what I had registered on the day” of the ceremony.

At this point, Mr. Koppe voiced an objection. While explaining that he was “a little puzzled” as to Mr. de Wilde’s line of questioning, he thought the prosecutor might be seeking for the witness to speculate. “It’s not about what he believes, it’s about what he knows,” Mr. Koppe suggested instead. Mr. de Wilde explained that he was trying to ascertain whether the witness attended more than one gathering at the Olympic Stadium, and as such, he was entitled to ask the question.

The president appeared to stare off into the middle distance for some moments, pondering this point, while the parties waited expectantly. Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne could be seen taking his headphones off in anticipation of a conference of Trial Chamber judges, which indeed took place a moment later. After this, the president advised, while thumbing through tabs of a folder, that the objection was sustained and Mr. de Wilde should rephrase his question.

The prosecutor asked Mr. Se whether the meeting that he attended might have taken place when the meeting described in the Revolutionary Flag was held. However, he was again interrupted, this time by Mr. Vercken, who suggested that the right approach was to ask the witness to consider the dates in question and then determine whether the meetings were the same, rather than “cornering the witness” with this suggestion.

Mr. de Wilde agreed to “go step by step” but did not “want to belabor the point.” He then asked Mr. Se whether the topics discussed at the “grandiose” meeting described in the Revolutionary Flagwere the same as those discussed at the meeting the witness attended. Mr. Se agreed that they were but explained that he could not recall the exact date of the meeting he attended because he did not take notes of the meeting.

Witness’s Transfer to Ratanak Kiri Province and Experiences until the End of 1976

Moving to a new issue, Mr. de Wilde asked the witness when he arrived in Ratanak Kiri province. “I was there by late 1975. It took us rather long because we had to cycle there from Kratie … we went by boat from Phnom Penh to Kratie,” Mr. Se responded.

Mr. de Wilde asked the witness to supply details of the mission of Division 801. Mr. Se said that the division’s role “was to be deployed to fend off the country from the external forces at the border — Cambodia’s border with Laos. He clarified, “To make it clear, that division comprised of three regiments. These three regiments had to cover different parts of the country, including the border with Vietnam.”

What was the view of the Vietnamese at that time? Mr. de Wilde said. Mr. Se explained the evolution of the relationship between the Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese by stating, “We were friends at the beginning. Later on we were half-enemies, half-friends. The borderline was not properly marked, so we could still clash. At that time, we couldn’t regard the Vietnamese as either our friends or enemies very clearly. But indeed, enmity increased.”

Mr. de Wilde asked the witness to identify the three regiments the witness had described Division 801 as comprising. At this point, National Co-Counsel for Nuon Chea Son Arun objected that he heard Mr. de Wilde using the terms “regiment” and “brigade” interchangeably, seeking clarity on the intended meaning of his question. Mr. de Wilde explained that this was likely a translation issue and that he sought to know details of the regiments under Division 801. Mr. Se duly shed some light on this issue, stating:

Under 801, there were three regiments and three battalions. The first regiment was Regiment 81. Regiment 81 was tasked to patrol Road 19 to the north. From O Sethey to the Dragon’s Tail[19]was for Regiment 83. From the north to Dalao was the task of Regiment 82. For the three battalions and four transport units, they were to patrol the area near the river. I personally was tasked as the head of the company. In 1975, when I got there for a period of more than one year, I worked in the military to patrol the area along the Sesan River from Otres region to the Oyada border to O Sethey all the way to the Dragon’s Tail.

At this point, the president requested Mr. Se to confine his responses to only the question asked. Mr. Se then advised, in response to questions from Mr. de Wilde, that So Sarun was the division commander, while Pao Som Ol was his deputy. The witness confirmed under questioning from the prosecutor that there was a special unit dealing with logistics, and advised that this unit was numbered 806.

Moving on, Mr. de Wilde noted that in his testimony before the OCIJ, the witness had said that Ta Ya was in charge of the Northeast Zone before being replaced.[20] Mr. de Wilde asked the witness what he knew of Men San alias Ta Ya. The witness said that he did not know the details of Mr. Ya’s disappearance “because he was holding a senior position” but that “he disappeared in 1977.” Mr. de Wilde asked the witness who told him this, but Mr. Se said it was a “long story” and he thought he could not recall it all. The story, he explained, “related to the zone, and it was an internal affair, and I had no authority to be informed.”

Mr. de Wilde was granted permission to show and read to the witness the precise excerpt of the witness’s answer to the OCIJ on this issue. It read as follows:

After liberation day on April 17, 1975, Ta Ya was chairman of the Northeast Zone. Ta Pao[21] was responsible for the soldiers of the zone. Ta Ya disappeared in 1977. Indeed, he had been summoned to go and work in Phnom Penh, and then he was arrested. I learned this in the information meeting. During the meeting, we learned that he had been affiliated with the Vietnamese, and then he rallied with the Chinese. Ta Ya had been a member of the Central Committee.[22]

Asked whether it was normal for high-ranking cadres to be summoned to Phnom Penh, Mr. Se agreed that it was “true.”

Relationship between Division 801 and the Northeast Zone

Mr. de Wilde asked the witness to enlighten the Chamber on the relationship between Division 801 and the Northeast Zone and whether that zone had its own army. Mr. Se explained, “It was our intention to cooperate, to usually assist each other, because the zone was close to the area we were deployed. However, as low-ranking personnel, I did not know much about what happened at the upper level, and I had to focus on my tasks.” He continued, “I was supposed to … mind my own business. At that time, it was a transitional period for converting Communism into Socialism. I know some things” but I just don’t know everything.”

In response, the prosecutor asked whether the witness knew, as head of the O Kanseng security center, about any collaboration between the division and the zone. Mr. Se said:

When I came to control that center initially, I only knew of the role of the units and all the forces that were gathered from the battalions and the regiments. They were from the level of the company upward, and my level was rather limited at the time. I did not have the authority to receive those from the cooperatives or form the union. I was asked to control those within Division 801.

Mr. de Wilde was granted permission to show the witness Telegram 43, which had been sent by Division 801 to “Beloved Bang Oeun.”[23] This telegram had been sent by Lao and was copied to 99 and Archives. It dealt with enemies and specifically Om[24] Lao arresting two other enemies and requesting assistance and cooperation with arresting the two individuals. The witness confirmed he knew Lao but did not know about this specific incident. As to Lao’s role, Mr. Se advised, “He was a member of [the] Division 801 [Committee].” More particularly, Mr. Se said, he “had a leading role at the base.”

Witness’s Directorship at O Kanseng Security Center

Were civilians ever sent to O Kanseng Security Center? Mr. de Wilde inquired. Mr. Se agreed, recalling, “Civilians were sent to me in around 1977 – that is, mid-’77.” Asked whom specifically they were sent from (that is, either the administration of the Northeast Zone or Division 801), Mr. Se said:

I cannot recall exactly, but the base sent those people from the cooperative and from the union,[25] and they were both old and young people. However, it was the decision of So Sarun instructing me to receive them. I did not have the capacity to receive them but I could not deny So Sarun’s instructions, I agreed to take them temporarily. They stayed only temporarily and then they were once again sent to the base.

Mr. de Wilde asked the witness whether he knew if Mr. Sarun regularly met Ta Ya or Ta Lav. The witness said that he could not answer this as he was based quite a distance from Mr. Sarun.

After the mid-afternoon break, Mr. de Wilde asked the witness who had the authority to determine who enemies were – was it the Northeast Zone or Division 801? The witness explained that he did not know, prompting the prosecutor to characterize his question as a perhaps “convoluted” one, suggesting that he might return to this issue later.

Mr. de Wilde then asked the witness why O Kanseng security center was set up. Mr. Se professed his uncertainty but explained that what he knew was that “the situation at that time was chaotic. A lot of people in the army were not properly disciplined. For that reason, in each regiment, they had to make sure a system was in place to discipline those people who were free and ill. Each division had to properly manage this.” He continued, “That’s why a center was set up: so that the bad elements, the irregular elements, could be detained at the center.”

The witness had also testified to the OCIJ that the center housed “enemies developing throughout the country.”[26] Asked what he had meant by this, Mr. Se said, “Within the unit, people had been removed, people who were holding the rank of colonel and other senior people … Security was part of our primary concern. Enemies could take advantage of this opportunity to make the situation worse. That’s why the center was set up.”

The witness took on his duties at O Kanseng security center in “around late 1976,” and remained in control there “for about two years,” he testified. Mr. Se then explained, “People were arrested and sent to my center through the regiment under the decision made by the secretary of the division. Reports could have been filed before people were sent gradually to the correction center.”

As to whether there were limits in the rank of military personnel who would be sent to O Kanseng security center, Mr. Se advised, “It was [my] right and my capacity. I was holding the rank equivalent to the lieutenant. For that reason, people who were holding the rank of captain or major would not be subjected to this center. We received people who were the deputy chairmen of the Party branch.”

Those people could be sent to “only one location in Phnom Penh,” Mr. Se said, when asked. He elaborated, “I learned that these people who disappeared came to Phnom Penh for study purposes. Some came … by car or by helicopter.” Mr. Se learned of this because “this information could not be hidden forever. People could exchange it during conversation, because people noted the disappearance of other colleagues. People asked what happened to them. Then we learned about this.”

President Nonn appeared to interject at this point, but his comments were not rendered in either the English or Khmer channels.

Mr. de Wilde was then granted leave to read excerpts to the witness from a report sent on November 25, 1976, by Run of Division 801 to Uncle 89. He proceeded to highlight three segments. The first stated that all people arrested were from unit three.[27] The second detailed measures pronounced by Ta Sarun as to methods of dealing with enemies, specifically:

- Enemies had to be “absolutely arrested.”

- Those denounced should be temporarily arrested.

- Violators of discipline who did not change their behavior after re-education should be “cast aside” and “followed carefully.”

- Inactive, deceitful, or lazy squad cadres had to be removed.

- Those with political tendencies should be arrested.

- The good ones should be left alone.[28]

The third requested that “uncle make remarks and comments” and provide recommendations. After this preamble, Mr. de Wilde asked the witness whether arrested people made their confessions at the security center. This prompted an immediate objection from Mr. Koppe, who said it was uncertain how this line of questioning fit in within the appropriate scope for which questions on security centers could be asked in this trial.

Mr. de Wilde said that these questions related to re-education and were part of the organization of the division, communication between the center and higher ranks, and policies concerning the enemies and in particular, who had the power to decide on the enemies’ fate. These topics, he suggested, were all linked to O Kanseng security center and the witness could enlighten the Chamber on these subjects given his role as the head of the center.

The Trial Chamber judges conferred briefly. The president then advised that Mr. Koppe’s objection was not sustained, and Mr. de Wilde’s line of questioning was not relevant to O Kanseng security center per se but to the broader issue of military structure. Directed to respond to Mr. de Wilde’s question, the witness said that he “did not think he had any capacity to shed any light on this” although what the prosecutor had described seemed “consistent.”

Referring back to the various directives Mr. Sarun had given, Mr. de Wilde asked whether these directives were sent to cadres of Division 801 and implemented by them. Mr. Se responded, “I think the measures you quoted were consistent with those applied at different units, but this was not the case in my unit.”

The prosecutor asked whether the people who were sent to the witness at O Kanseng security center fell into the categories delineated in Mr. Sarun’s report. Mr. Se said that he did not know about this, as his task was to receive people.

On Confessions, Interrogations, and Executions

Moving on, Mr. de Wilde asked the witness to whom he was to report within Division 801. Mr. Se advised, “There were different means of reporting concerning economic and other affairs. 06 used to be in charge of this section. Later on, he did not ask me to report things to him and he asked me to report directly to the commander of the division.” Continuing, he explained, “We had to report to the head of the battalion. With regard to the report that we obtained from confessions, for example, we did not copy them to the heads of the battalion, but to the division commander instead.”

The frequency of reporting, Mr. Se said, depended on the urgency of the matter, though he was not precisely sure of this fact anymore. These reports were given to enable Mr. Sarun to decide whether the problems reported were “a systematic issue or an isolated incident” and “whether the person should be arrested or disciplinary action taken.” As to the kinds of decision Mr. Sarun would issue, Mr. Se said that it was “difficult to conclude” on this matter, because he did not personally receive any instructions to execute anyone. “Later on,” he said, there would be a need for a “thorough study and review of the process.”

Mr. de Wilde asked the witness how confessions from the Center in Phnom Penh were communicated to O Kanseng security center. Mr. Se advised that he receive the contents of these confessions “in a message from 05” and would consist of “names of people who had been implicated.” Mr. Se confirmed, once again, that 05 had been a code name for Mr. Sarun. As to how Mr. Sarun himself received confessions from Phnom Penh, Mr. Se said that “he had all kinds of radio communications at his disposal.”

As to the provenance of confessions received from Phnom Penh, and particularly whether they were confessions of cadres from both the Northeast Zone and Division 801, Mr. Se advised that the confessions were only from Division 801. However, he could not recall any ranks or names of those who had confessed, as it had “been a long time already.”

Mr. Sarun would, in his instructions, indicate to the witness if, for example, a matter was serious and further action needed to be taken, Mr. Se recounted. This prompted the prosecutor to ask whether Mr. Sarun ever asked the witness to conduct further instructions regarding implicated people. “In some instances, yes, as some had been implicated,” Mr. Se replied. “However, they were not of a serious nature. But they were afraid, and they attempted to escape. Then they were recaptured.”

The prosecutor asked the witness whether he had known a person called Keo Saroeun alias Seng. Mr. Se replied that he did know a Keo Saroeun but not his alias, and the person he knew was the commander of Regiment 81. What became of him? Mr. de Wilde asked. “Later, he became a member of Division 801, that is, towards the end of the regime. After a while, he was called to a study session in Phnom Penh, and he disappeared,” the witness answered. The prosecutor noted that the witness had testified to the OCIJ that Keo Saroeun disappeared in 1977. The witness agreed, when asked, that he stood by this.

Mr. de Wilde was granted permission to show the witness an S-21 prisoner list,[29] asking whether a person whose name was highlighted was indeed the Keo Saroeun referred to, which Mr. Se confirmed. Next, Mr. de Wilde repeated a technique Mr. Lysak had employed when questioning witness Ong Ren, by directing the witness to number 183 to 191 on that list. Perusing it briefly, the witness advised that he recognized only the names of Pao Som Ol and Touch Son.

The prosecutor was also permitted to draw the witness’s attention to Mr. Saroeun’s S-21 confession, which stated that there were “up to 58 enemies embedded in his network, some of whom were Chham, Lim, Nat, Tan, and Khieu Narong alias Bao.”[30] The witness advised that he knew the person named Chham, and this person had been “in charge of a battalion.” He had not been at O Kanseng because the witness “heard that he had been sent to Phnom Penh.”

When the witness heard that cadres were called to Phnom Penh, Mr. de Wilde queried, did he ever receive information about the entity that called them there? Mr. Se denied this, stating that “it was based on their own chain of command; that is, the instructions of their division commander.”

The prosecutor asked the witness whether Mr. Sarun ever advised the witness of a distinction to be made between people committing minor offenses and those to be monitored closely. The witness agreed that Mr. Sarun instructed him to consider “if the nature of the offense could be reduced. … I had to consider that. [It] depended on the severity of the offense.”

Who sent people from O Kanseng security center for execution? Mr. de Wilde queried. The witness responded:

I myself never issued orders for execution because they were not criminals, even if those people committed serious offenses and were shackled, since we did not have complete documents for those people. However, some caused injury to my guards … and as a result, one died. In a second instance, one person who was shackled escaped. That person was chased, and this resulted in his death. However, there was no instance at all of where people were released to work outside and were later executed. Secondly, regarding the group of six people, I received instructions from So Sarun for them to be executed.

According to his previous testimony,[31] the prosecutor said, Mr. Se had testified that “most executions of prisoners who were not able to be corrected took place in late 1978.” Mr. de Wilde asked if there was anyone else other than the six people to whom the witness had referred who were received by the Center and later executed. Mr. Se agreed that there were “three other people” who were executed “due to the harm they caused to my guards.” However, he testified, there was no one else.

The prosecutor asked whether Mr. Se ever received instructions from the “upper echelon of Division 801” regarding the need to torture individuals who refused to confess. Mr. Koppe again objected at this point, arguing that this did not fall within the scope of the trial, as it was no longer about the structure but about actual executions. Mr. de Wilde said that his question was about the issuance of orders, and thus concerned internal communications between Division 801 and the Center. “In the final analysis,” he suggested, this meant his question was appropriate.

The Trial Chamber judges huddled in conference briefly at this moment. Following this, the president entreated Mr. de Wilde to rephrase his question and ensure it was one that clearly connected to communication rather than functions of O Kanseng security center.

Referring to his previous question, Mr. de Wilde asked Mr. Se whether he had the power to order the release of detainees. The witness indicated that this was within the authority of the division secretary only. The prosecutor asked whether that division secretary, Mr. Sarun, ever advised the witness of having to report to the Center and wait for their decisions with respect to such cases. Mr. Se replied that this “was part of confidential policy and I believe that we did not have the right to be informed.”

At this point, the president adjourned the hearing for the day and week. Hearings will resume at 9 a.m. on Monday, January 14, 2013, with the continued testimony of witness Chhaom Se.