Fall of Phnom Penh Comes to Life in Photographer’s Eyewitness Testimony

On January 28, 2013, American photojournalist Al Rockoff provided detailed eyewitness testimony in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on the events before, during, and in the aftermath of the fall of Phnom Penh. Mr. Rockoff, a former U.S. military serviceman, had been in Cambodia since 1973 and was evacuated from the country along with other foreigners taking refuge at the French Embassy after Phnom Penh’s fall in May 1975.

On January 28, 2013, American photojournalist Al Rockoff provided detailed eyewitness testimony in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on the events before, during, and in the aftermath of the fall of Phnom Penh. Mr. Rockoff, a former U.S. military serviceman, had been in Cambodia since 1973 and was evacuated from the country along with other foreigners taking refuge at the French Embassy after Phnom Penh’s fall in May 1975.

In a powerful day of testimony peppered throughout with striking photographs taken by Mr. Rockoff and others, the witness offered captivating insight into some key events occurring in Phnom Penh at that time. In particular, Mr. Rockoff relayed his recollection as one of a small coterie of foreign journalists who were present at a meeting at the Ministry of Information when remnants of the Lon Nol regime attempted to negotiate their fate with the Khmer Rouge.

Mr. Rockoff was also one of the few foreign journalists on the streets of Phnom Penh on the day of the evacuation. Through both his testimony and photographs, Mr. Rockoff painted a vivid picture of the Khmer Rouge capturing Lon Nol soldiers and weapons and a gradual darkening in mood following the joy of the initial announcement of the Khmer Rouge victory.

As one of the few people inside the French Embassy during the evacuation of the city, Mr. Rockoff was able to provide an insider’s perspective into events within its walls. Strikingly, he detailed how some Cambodian nationals and others were forced out of the compound. He also relayed his experiences of traveling in the embassy’s last convoy, fleeing for the Cambodian-Thai border through a deserted Phnom Penh and a country marked by the occasional whiff of corpses.

A Delayed Start and Debate over Available Time

Hearings were delayed by nearly 20 minutes this morning, with an audience of 156 villagers from Takeo province, as well as the Khmer Rouge historian and former OCP investigator Craig Etcheson and several media representatives, waiting patiently in the public gallery. No explanation was offered when the Chamber eventually convened. Instead, Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn advised the parties that today the court would be hearing from the witness Al Rockoff, an American photojournalist. This testimony marked a short interlude in lengthy hearings where parties have been presenting and discussing documents relevant to Case 002/1 and in particular, those relating to the Khmer Rouge military structure, the first and second phases of forced movement, and the Tuol Po Chrey killing site.[2] Those document hearings are scheduled to resume on Wednesday, 30 January, 2013.

Of the three accused persons, only Khieu Samphan, recently discharged from the Khmer Soviet Friendship Hospital, was present in the courtroom this morning. Nuon Chea is still admitted to that hospital, while Ieng Sary was participating from his holding cell due to health reasons. Additionally, Trial Chamber Greffier Se Kolvuthy reported that National Lead Co-Lawyer for the civil parties Pich Ang was absent due to his other commitments.

Before moving into Mr. Rockoff’s testimony, the president took the opportunity to rule on a request from Mr. Chea, submitted on January 25, 2013, asking to waive his right to be present for Mr. Rockoff’s testimony. Mr. Chea had submitted this waiver in hospital through his counsel. On that note, the president noted that Mr. Chea’s “health is improving significantly” and it is expected that he will be discharged shortly and is mentally fit. As such, the president acceded to Mr. Chea’s request.

At this juncture, the president ceded the floor to International Co-Counsel for Ieng Sary Michael Karnavas. The defense counsel advised that he had some preliminary remarks concerning a request made on Friday, January 26, 2013, at 3:05 p.m. by the Office of the Co-Prosecutors (OCP) to have more time to prepare for the questioning of Mr. Rockoff, since they reported that they had suddenly realized that Mr. Rockoff might have more testimony to give, and as such, requested more time for this. Mr. Karnavas advised that while they would not normally object to such a request, it would in this case because:

- The OCP had filed its request too late, and after it was known that Mr. Rockoff was going to be scheduled to testify;

- Last week, Mr. Karnavas had heard a prosecutor referencing Mr. Rockoff and that he would have relevant information; and

- Everyone knew Mr. Rockoff, since he is an “institution” in Phnom Penh, and was made infamous by the Killing Fields film where he was played by the actor John Malkovich.

As this witness was neither a “surprise” nor “inconsequential” witness, Mr. Karnavas concluded, such a request was not timely and should not be entertained.

By way of response, International Assistant Co-Prosecutor Dale Lysak expressed his “surprise” to this objection. Requests for more time were frequently made in the Chamber even on the day that a witness testified, he said. Moreover, it was only at 1 p.m. on Friday, January 26 that the Nuon Chea Defense Team advised that they would be willing to waive his presence for this testimony, and the newspapers had only reported the day before that Mr. Chea would not provide a waiver, he noted; thus, the scheduling of this witness was something of a surprise. The OCP would “proceed diligently,” but it also seemed that court time tomorrow might not be used if the OCP finished with the questioning of Mr. Rockoff today. Therefore, he said, if the parties required additional time, the time tomorrow appeared to be available.

After a brief conference with his colleagues on the bench, the president advised that the Chamber would assess the situation as it unfolded.

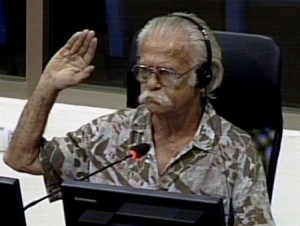

Photojournalist Recalls Being Injured on the Battlefield in Kampong Chhnang

Following this lengthy prelude, the witness took the stand, sporting a Hawaiian shirt, slicked-back long salt-and-pepper hair, and a full moustache. Under questioning from the president, he advised that his full name is Alan Thomas Rockoff. Mr. Rockoff, 64 years old, is a resident of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in the U.S. His wife is named Victoria Bornice, and they have no children. In a break from the Chamber’s usual tradition of having witness swear oaths outside the courtroom, Mr. Rockoff took his oath in the courtroom, placing his hand upon a Bible and repeating the requisite phrase. Mr. Rockoff then confirmed that has not given any interviews to the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (OCIJ) to date.

Taking the floor, Mr. Lysak began the OCP’s questioning by asking Mr. Rockoff to provide details of his career as a photographer. Mr. Rockoff advised that he started photography while “on active duty in the United States army.” He started his service in Germany and was then transferred to Vietnam, where he began his photography. After being discharged from the army, Mr. Rockoff moved to Cambodia, living in the country between April 1973 and May 1975, where he worked as a freelance photographer.

Asked whether the U.S. bombing campaign was ongoing when Mr. Rockoff was in Cambodia, the witness confirmed this, explaining:

Yes, the American bombing campaign did not stop until August 15, 1973. … I remember that date very well. I remember I was out on Highway 3 most of that morning. Right around 12 noon, which was supposed to be the end of the American bombing campaign, there were a few bombing missions in the vicinity, and then it stopped. So I have a very clear recollection of August 15.

At the time, there were very few areas Mr. Rockoff could work “beyond a 20 to 30 kilometer distance from Phnom Penh.” Some provincial towns could be flown to, and it was also possible to “hitch a ride” in military helicopters, he recounted. Otherwise, Mr. Rockoff generally covered Highways 1, 4, and 5, where battles took place.

One of the places Mr. Rockoff visited during those early years was Oudong.[3] He visited in 1970 while he was part of the “U.S. incursion into Cambodia.” However, he did not cover the “B-52 mistaken strike on the town.” Mr. Rockoff did recall Oudong being retaken by Lon Nol soldiers but could not recollect the approximate date of this event. Mr. Lysak asked whether the witness was able to visit the town after this point. Mr. Rockoff denied this.

However, Mr. Rockoff did recall spending time in Kampong Chhnang at the “beginning of October 1974.” He described:

There was a significant battle going on between the Cham[4] brigade and the Khmer Rouge. I had also gone to Kampong Chhnang to help recover the body of an Associated Press (AP) Cambodian photographer named Lim Sovath. He had been killed five days earlier, and I was with a group of Khmer soldiers who helped recover his body, and it was sent to Phnom Penh for his family to cremate. I stayed up there, and the day after helping to recover Lim Sovath’s body, I was seriously wounded, and I was medically evacuated out of there. …

[I was injured from] shrapnel from a burst in a tree maybe 20 meters from me, maybe a mortar or a recoilless rifle. I was wounded very seriously: shrapnel in my wrist, a few other parts of my body, and I had a piece go through the right atrium of my heart. The Korean photographer Joseph Lee, who I was with, was wounded also. We were taken back to a field hospital where I had surgery, emergency surgery maybe 45 minutes to an hour after the initial wounding. I was operated on by a Red Cross surgical team. … They stabilized my condition. I had a two-minute cardiac arrest.About 1 a.m., 2 a.m., I was flown out by a twin engine aircraft that landed on a highway. I was flown to Saigon to a military hospital where they stabilized my condition, and I was flown to the Philippines.

He returned to the country approximately five weeks later, but “it took a couple of months to recuperate,” Mr. Rockoff concluded.

Before the Storm: Phnom Penh before the Evacuation

Moving ahead in the chronology, the prosecutor asked the witness whether, between February and early April 1975, he ever heard of the phrase “seven super traitors.” Mr. Rockoff agreed that he had heard “second- or third-hand” about mention of a clique of traitors that overthrew Sihanouk.” However, he added:

The reports extended beyond this and also touched on the fact that when the war was over, everyone would go back to where they came from. … It was easy for many people to believe that, as the majority of the population of Phnom Penh was refugees, more than two million [people].

This prompted Mr. Lysak to press further, inquiring whether the witness had heard a National United Front of Kampuchea (FUNK) and Royal Government of National Union of Kampuchea (GRUNK) communiqué that stated:

Concerning the seven traitors in Phnom Penh, the National Congress has decided as follows: traitors Lon Nol, Sirik Matak, Son Ngoc Thanh, Cheng Heng, In Tam, Long Boret and Sosthene Fernandez are … the ringleaders of the treacherous anti-national coup d’état. On behalf of the FUNK, GRUNK, and CPNLAF [the Cambodian People’s National Liberation Armed Forces] … [it is] absolutely necessary to kill these seven traitors.[5]

Mr. Rockoff indicated that he had not read this document, but “did hear about the fact that these people were to be put to death.” He did not know “how widely known that [fact] was,” as he heard it as a freelance photographer and through reading releases from the AP or the New York Times. Neither did he ever personally hear any Khmer Rouge radio broadcasts.

Moving ahead again to the period prior to April 1975, Mr. Rockoff said he “had a very inexpensive room in what is now known as the Hotel Asie on Monivong Boulevard.” This prompted Mr. Lysak to ask whether Mr. Rockoff ever spent time in what was then known as the Hotel le Phnom. Mr. Rockoff agreed that he did, to visit journalists who “could afford to stay there.” It was “one block away from the Ministry of Information, who did a daily briefing for the press.” At the Hotel le Phnom, Mr. Rockoff could connect with the AP, which had a bureau there. He also had a “way to pick the lock” of a long-term room kept by the Los Angeles Times and would therefore stay there occasionally. Mr. Rockoff confirmed, when asked, that the Hotel le Phnom was situated where the Hotel Raffles Le Royal is now located.

Elaborating on events that transpired at that hotel, Mr. Rockoff described how Red Cross personnel also lived at the Hotel le Phnom. He recalled:

There were bungalows out back some agencies rented on a regular basis. About a week before the end of the war, about the time of the American evacuation on April 12, the International Red Cross declared that as a safe zone. There was a large banner hung in front of the hotel with a red cross. They were admitting people that needed immediate medical attention. There were thousands of people milling around trying to gain access to the hotel. The Red Cross had set up a surgical theater at the back of the hotel. But, on April 17, regardless, they were kicked out, with everybody else.

The Evacuation of Phnom Penh: Movements and Weapons of Khmer Rouge Soldiers

At this point, the prosecutor showed the witness a photograph from a book by the French photojournalist Roland Neveu.[6] Mr. Rockoff confirmed that the photo — a high contrast black and white photograph of a desolate hotel with a large Red Cross banner hanging from the windows and two trucks out front, one of which was emblazoned with the red cross — did indeed depict the hotel of which he had been speaking. However, he noted that he found it strange that there were no people in the photograph, as he recalled seeing “hundreds, and then, in the end, thousands of people milling around.”

Mr. Lysak asked the witness to explain his recollection of the first events of the evacuation of Phnom Penh. Mr. Rockoff obliged and described:

The night of the 16th, I was down at the Post Telegraph office along with a few other journalists that include[d] Sydney Schanberg [of the] New York Times; Jon Swain. They were still able to get copy out [as] the teletype was still working. There was a huge fire on the other side of the Monivong Bridge. The shelling was intense on the Chroy Changva peninsula.[7]

The first indication I had of the Khmer Rouge entering the city was around maybe 8 o’clock in the morning, going back towards the Hotel Royal. The armored personnel carriers that were lined up in front of the Hotel Royal for the past couple of days, a few of them headed north, past the French embassy, and shortly afterwards brought a few political cadres back, and stopped in front of the Catholic cathedral that used to stand off of Monivong near the Royal. Huge crowds of people started gathering. A cadre with a bullhorn was saying, “The war is over, the war is over.” Everything was okay at that point. People were not panicking, they were happy: the soldiers, the civilians. About an hour later, the mood changed.

Around 8 a.m., by the Hotel Royal, [I first saw] the Khmer Rouge soldiers that I just mentioned coming south from by the French Embassy. There were other groups coming from other directions. A group from south on Monivong met up [with the other group at the French Embassy.] A few of them broke off, went east, I think [to the] Street 108 area, the former location of the Ministry of Information. A few ran into that [compound], to secure that.

I spent the next two hours, three hours, going through parts of the city hitching a ride with the Khmer Rouge. It was easy to travel around in the first hour. I got as far as the Independence Monument, and then I went back to the intersection of Monivong and Sihanouk Boulevards, where I stayed nearly an hour. I photographed the collection of weapons; disarming of soldiers; a large group of soldiers traveling under guard being sent towards the Olympic Stadium.

I was standing next to Roland Neveu, and one of the cadre came up to him and asked in French, “Where are the Americans?” Roland Neveu said, “They departed.” I was very glad he did not ask me because I do not speak French. A few minutes later, some more Khmer Rouge came by. They saw my walking in the midst of a bunch of government prisoners, and I was just trying to get to the next block, and then a jeep with some Khmer Rouge, a guy puts his hand up; they stopped. I was very concerned. I went off to the right and hid behind a truck, maybe two minutes, three minutes. And then I came out, it was no problem. I just did not want someone stopping me, asking me in French, “Who are you?”

I started to head back north on Monivong Boulevard, and a white Peugeot driven by a Cambodian in hospital scrubs … was driving. He stopped the vehicle. I was trying to get a ride. I got in, and he started talking French. I said, “I do not understand.” He said, “Where are you from?” I said, “America.” He got very nervous. Then he said, he just got back from Preah Ket Mealea Hospital, and people were being put out of the hospital.

I was dropped off at the Hotel Royal, I walked in to the hotel, I saw, right off, Dith Pran, Cambodian assistant to Sydney Schanberg. I mentioned where I just came from. Sydney came up. We went in … Sydney’s vehicle down to the Preah Ket Mealea Hospital.

At this point, Mr. Lysak directed the witness to provide some observations concerning the age of Khmer Rouge soldiers who he saw first entering Phnom Penh. Mr. Rockoff responded:

There were quite a few young teenage soldiers. To give an approximate age, I can’t say, maybe 16, give or take a year. That’s also what I would see out on the battlefield after casualties. … [All the] Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol soldiers [were] very young.

Mr. Lysak showed the witness another photograph. Mr. Rockoff recognized this as a photograph he took on the morning of April 17, 1975. The photograph depicted a young boy dressed in black pajamas, holding a cigarette and brandishing a large weapon, perhaps a rocket launcher or machine gun. A crowd of approximately 100 civilians could be seen in the background.[8] Mr. Rockoff said that this photograph was taken on Monivong Boulevard and showed a young Khmer Rouge soldier.

The prosecutor asked how old this Khmer Rouge soldier appeared to be. This prompted an objection from International Co-Counsel for Nuon Chea Victor Koppe, who argued that Mr. Rockoff had no particular expertise in this area. Mr. Lysak responded that this was a matter of life experience and not special expertise. Mr. Rockoff guessed that this soldier may have been “16, 17.” The soldier was carrying “two bayonets, a grenade, and I assume ammunition in some of the pouches.” This was the same equipment as that used by Lon Nol soldiers, Mr. Rockoff said. He then clarified that the soldier was holding an “American M-16,” which is a semi-automated military grade rifle.

As to the weapons carried by the Khmer Rouge generally, Mr. Rockoff described that the majority of the Khmer Rouge soldiers carried “AK-47s, some M-16s … some B-40s, also known as RPGs [rocket-propelled grenades]. He continued, “It was mostly light weapons. Any armored personnel carriers that the Khmer Rouge were driving around in, any military vehicles: these are what they obtained on the morning of the 17th.”

At this point, Mr. Lysak sought to show the witness another photograph from Mr. Neveu’s book The Fall of Phnom Penh, although first clarifying that this was because he had been advised that some of Mr. Rockoff’s photos were water-damaged and the negatives were in the U.S. The first photograph showed two men wearing black, with the first carrying a large weapon looking like a rocket launcher and the second carrying another long weapon.[9] Mr. Rockoff explained that the first was carrying an RPG and the second, “a grenade launcher called the M-79.” The photograph was taken on Monivong Boulevard, he added.

This prompted Mr. Lysak to ask Mr. Rockoff how he could distinguish between Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol soldiers. Mr. Rockoff said, “It is not always easy to differentiate based on the uniform; there’s such a mix of uniforms. But, when the Khmer Rouge entered the city at 8 a.m. on April 17, the government soldiers were not armed. That’s the big difference.” When prompted, Mr. Rockoff added:

Many Khmer Rouge had flip-flops. Many did not have shoes. Some had so-called “jungle boots” manufactured by the Americans. Sometimes they were acquired on the battlefield. There are ways of getting boots. … I mean, I was wounded one time, and I had my boots stolen from me. … I had been in the field with government troops, and even though they were well-equipped, they had flip-flops, sandals. I did not see the … so-called “Ho Chi Minh sandals.” There were some on the Khmer Rouge. … But [for] the government troops, if you were in a good unit and your colonel took care of you, he would provide you with boots.

Moving on to describe communications between the Khmer Rouge during the evacuation, Mr. Rockoff explained:

There evidently was a very good radio network going. Some Khmer Rouge had a U.S. radio unit, named a PRC-25. There were also Chinese units going around. … I did not see that many radios. But usually, with somebody who was obviously in charge, you would have a radio operator close by.

Another photograph taken by Mr. Neveu was shown to the witness; there appeared to be a picture of a group of soldiers standing in front of a row of trees, with weapons on the ground. Some were smiling, and others had their hands in the air and were smiling.[10] Mr. Lysak asked the witness to focus on one of the soldiers in the center, asking what equipment he was holding. Mr. Rockoff said that as the photograph was “not real clear,” it was hard to say, but it appeared to be the “handset of a radio.”

Lon Nol Soldiers Disarmed and Marched to Another Location

Mr. Lysak asked the witness whether, during his travels around Phnom Penh during its evacuation, he ever saw Khmer Rouge who had come from and were occupying the city’s southern sector. Mr. Rockoff explained:

I saw a good number of Khmer Rouge headed in a northern direction, coming towards the Independence Monument.[11] These guys looked very dirty, tired, not in a good mood, and obviously were coming from an area of the city where there was a considerable amount of fighting — the other side of the so-called Monivong Bridge. I decided not go to further south. I headed back north from the Independence Monument a little way, and then over to Monivong, then back to the intersection of Sihanouk and Monivong.

I stayed there for maybe an hour. A very, very small pile of weapons in the middle of the intersection then grew to several hundred. There were many Khmer Rouge just hanging around there, not doing anything. There were Khmer Rouge going around in a truck giving out sodas, Pepsis, and ice. Everybody was in an okay mood; there was no tenseness. The civilian population was looking on but kept back on the sidewalk. The photograph of mine showing the Khmer Rouge soldier in the foreground with an M-16, that building in the background used to be a movie theater and is now the site of a gas station.[12] That intersection became the collection point of many, many truckloads of weapons. Young students and some boys probably too young to be students were charged with collecting weapons, unloading them from the trucks.

The next of Mr. Neveu’s photographs to be shown to the witness depicted a young man, wearing black, and standing in front of a pile of weapons.[13] Mr. Rockoff confirmed that this image “looked like a photograph of a collection point of weapons from Lon Nol soldiers,” and he believed this was taken “at the intersection of Monivong and Sihanouk [Boulevards].”

“I did not see anyone being taken away from the city by the Khmer Rouge,” Mr. Rockoff explained, when asked. “In fact, there was no mass movement out of the city for the first few hours.”

At this point, Mr. Lysak turned to the subject of the journalist Jon Swain, who the witness had mentioned earlier. Mr. Swain is a “British journalist, a writer,” Mr. Rockoff said, and the two spent time together on “the afternoon of the 17th and also for the next three weeks.” Mr. Rockoff confirmed seeing Mr. Swain writing in a journal. At this point, Mr. Lysak read the witness a passage from Mr. Swain’s book River of Time. In this passage, Mr. Swain wrote:

Rockoff, the photographer, came back from the southern sector, saying the Khmer Rouge there were grim-faced and seasoned soldiers. Their mud-stained feet and uniforms showed they had not been pussyfooting around. They were disarming government soldiers, stacking all weapons into huge piles, throwing away the boots, and marching the men out of the city to unknown destinations.[14]

Al Rockoff (left) with Francoise Demulder during the 1970s. (Photo: Catherine LeRoy)

Mr. Rockoff denied telling Mr. Swain this account. What Mr. Swain might be referring to, the witness said, was his description of soldiers being disarmed and “marched westerly past the intersection I was at, at Monivong and Sihanouk Boulevards. I had to assume they were being taken to the Olympic Stadium. A Cambodian told me that. That does not equate to being taken out of the city.” Mr. Rockoff added, “About one third of them had their hands up.” Mr. Rockoff said that it would be difficult to estimate how many Lon Nol soldiers there were, as at one point, he veered off to hide behind a truck.

Another photograph by Mr. Neveu shown to the witness portrayed a group of soldiers marching, with one soldier in the foreground holding up his hands, grinning widely, and waving a small white flag.[15] Another showed the backs of some soldiers and a large number of men passing by in front of them.[16] Mr. Rockoff said that this appeared to be the group of soldiers he earlier mentioned — that is, the Lon Nol soldiers, although he qualified that “they weren’t smiling” when he saw them. Mr. Rockoff saw these soldiers pass approximately in the “late morning,” although he was not wearing a watch at the time. He added that he and Mr. Neveu were not together for the afternoon that day.

Focusing on the photograph of the backs of soldiers and other people marching past, Mr. Rockoff said that he was “pretty sure that is the intersection of Monivong and Sihanouk.” When prompted, he confirmed that “this is an accurate portrayal of what I saw that day. It’s also in photographs that I took.” At this juncture, the president adjourned the hearings for the mid-morning break.

Mr. Rockoff’s Second Brush with Death under the Japanese Bridge

When the Chamber resumed, Mr. Lysak noted that, as discussed with a Trial Chamber greffier this morning, copies of some of Mr. Rockoff’s photographs had been damaged. The OCP had accordingly contacted the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) requesting copies of Mr. Rockoff’s photographs and had just received an electronic file from DC-Cam with these attached. Mr. Lysak advised that the OCP would review this file and circulate it to the parties.

Next, the prosecutor directed the witness to explain in more detail when the mood of Phnom Penh darkened. Mr. Rockoff testified:

Around midday, people started leaving the city, going out towards the edge. The word going around, and also being put out by cadres with loudspeakers, was, “You have to leave the city: Americans are going to bomb.” Also, the mood changed for me significantly after the incident at Preah Ket Mealea hospital.

As for whether there was any looting by the Khmer Rouge, Mr. Rockoff stated, “If there was, I did not witness it personally.” Mr. Lysak asked whether the witness conversely saw the Khmer Rouge engaged in the protection of homes, business, and property of Phnom Penh residents. Mr. Rockoff stated:

I cannot say that I saw that myself. An incident was related to me during my time in the French embassy by an Austrian cinematographer, Christoph Maria Schröder. He took 16 millimeter movie film; … [one is] a photograph showing a Khmer Rouge cadre with a 45 caliber pistol in his hand. … Christoph said he was trying to get the people to move on, the Khmer Rouge, to not go into a store. Whether or not that was looting or not, I can’t say. But he did not fire at anybody.

Now investigating the incident Mr. Rockoff had touched on at the Preah Ket Mealea Hospital, the prosecutor asked the witness to detail that event. Mr. Rockoff responded:

I am not sure what time [I went there,] I did not have a watch. I’m also very bad at keeping notes or captions for photos, but the reason I went to the hospital is, as I related earlier, I was leaving the intersection of Monivong and Sihanouk and a white Peugeot stopped, and I got a ride with a person who worked at the Preah Ket Mealea hospital. He was still in his hospital uniform. He seemed extremely nervous, and even more so when he realized I was an American. He told me the Khmer Rouge were emptying the hospital; everybody had to leave work.

So I got off by the [Hotel] Royal, saw Dith Pran, Sydney, Jon Swain. We went down to the hospital, went into one of the buildings; there were bodies on the floor, blood everywhere. [It was] easy to slip on the blood, it was wet. There were many wounded. There was a Khmer Rouge cadre in a truck outside who had just lost an eye to shrapnel. I photographed him outside, then went inside, and one of the French doctors was working on him. … [We] went out [of] the building and the Khmer Rouge came in to the front of the hospital.

The next five minutes were very intense. They were asking Dith Pran questions. I cannot speak Khmer, so I don’t know what was transpiring. They tried to get him to go away, but he refused, he stuck with us. They put a pistol to my head. The two behind me moved aside, I guess so that they would not get splattered. Next thing, we were told to get into this armored personnel carrier (APC), which formerly was a Lon Nol force APC. A government driver was in it. They put us in the APC, we drove maybe, it’s hard to say how far, because the hatches were shut, it was dark. Could have gone maybe a kilometer; stopped. They threw a naval officer in. He threw his wallet under the bench behind some ammunition cans. He was very, very nervous.

We rode around for a few minutes, and eventually the APC stopped. It seemed to turn … maybe 90 degrees on its track, and backed up. A bright light came shining in, and we saw the river. We were told to go and stand under the remains of the Japanese Bridge. The Cambodian naval officer was led away. Whatever happened to him did not occur in my presence.

We were detained there for maybe an hour. I’m sorry, I cannot tell you approximately because it’s hard to get a handle on the flow of time in a situation like that. We were detained for a while. You could see many, many people streaming past; you could see the pace of the evacuation was picking up. About an hour after being detained, we were told to go to the Ministry of Information.

At this point, Mr. Lysak sought to investigate further some of the points Mr. Rockoff had just mentioned. He first asked who it was that put Mr. Rockoff in the APC. Mr. Rockoff said it was approximately a “good half dozen” Khmer Rouge. The captured group was Mr. Rockoff, Mr. Pran, Mr. Schanberg, Mr. Swain, and Mr. Schanberg’s driver, who Mr. Rockoff believed was named Sarun. Mr. Lysak asked if there were some among the party who the Khmer Rouge were particularly interested in. Mr. Rockoff said that perhaps Mr. Pran had told the Khmer Rouge that some people in the party were French journalists and this “may have helped in them not separating us.”

The prosecutor read to the witness the following excerpt from Mr. Swain’s journal: “Mr. Pran explained that the Khmer Rouge had told him he was free to go, that they were only after the rich and the bourgeoisie.”[17] Asked whether this refreshed his memory regarding his capture, Mr. Rockoff said that “it was never explained to me why we were being taken into custody.”

The gun pointed at Mr. Rockoff was a “small caliber … revolver,” not of a military grade. The Khmer Rouge soldier was “maybe three feet away,” so that when his arm outstretched holding the gun, “he was very close.” Mr. Rockoff did not know for sure whether the group had a commander but assumed “somebody must have been in communication with the higher-ups.”

As for whether Mr. Rockoff’s party was personally interrogated, the witness explained:

There was no intense questioning going on [involving the foreign journalists]. The conversation was between Dith Pran and the Khmer Rouge. I am not in a position to understand what was being discussed. Sydney stated that he was telling them that we were French journalists covering the victory. He told me that rather quietly, just so I would catch on, just like Sydney got very upset and nervous when we were in the APC and I started talking in English and he said, “Don’t speak English. We’re French.”

The hour under the bridge: no interrogation, no nothing. They were satisfied we were journalists and, I guess, waited for instructions on what they were supposed to do. In the meantime, they took an interest in what was in our bags, what was in Sydney’s bag. They rummaged through his bag. One Khmer Rouge held up a big wad of hundred dollar bills in one hand and Sydney’s underwear in the other. He put the money back in the blue handbag and kept the underwear. I guess the money had no value to him. I was worried they would be going through my camera bag next, and then we were told to get to the truck. I had my camera equipment and film I had shot with me. I was very fortunate because if they had not been returned to me, it would have been all for nothing.

Mr. Lysak asked whether the Khmer Rouge attempted to learn whether any of the group was American. Mr. Rockoff said he was not aware if they asked Mr. Pran these questions, and “I did not speak English in front of them. It’s that simple.”

Mr. Rockoff testified, when asked, that he knew that the naval officer was part of the military because the man, when “physically thrown in” to the APC with them, was wearing his naval uniform, as “he failed to take his uniform off that morning.”

When they arrived at the riverfront near the Japanese Bridge, the witness continued, “I could not give you an approximate number, but there were a number of Khmer Rouge there, just as all along the river, there were a number of Khmer Rouge at various intervals. … I would say approximately two dozen” Khmer Rouge soldiers were at the Japanese Bridge.

Mr. Lysak returned once more to the subject of the naval officer who was loaded into the APC. He noted that in Mr. Swain’s journal, his account of the naval officer was as follows:

We rode through the streets, then stopped and picked up two more prisoners: Cambodians in civilian clothes. The big one with a moustache and crew cut wore a white t-shirt and jeans. The smaller man was clad in a sports shirt and slacks. Both were officers and quite as frightened as we were. The big man we recognized as the second in command of the navy.[18]

Mr. Lysak asked whether this refreshed Mr. Rockoff’s recollection as to the number of Lon Nol officers who were picked up on Mr. Rockoff’s trip in the APC and their appearance. Mr. Rockoff said:

I remember the one officer who put his wallet under the seat. About the second, I’m not sure, I’m hazy on that point. I was focused on the one guy sitting directly across from me, and what he was doing. I was sure he was military, but regarding having the full military uniform, no. Pants and shoes; a t-shirt [yes]. I did not know how high ranking he was. I don’t know if Dith Pran was able to recognize him. You say third person or fourth person in the navy; no. I’m bad with names.

Mr. Lysak asked whether, in reference to the streams of people Mr. Rockoff saw leaving the city, the witness saw the Khmer Rouge use force or threats to persuade people to leave the city. Mr. Rockoff denied this and elaborated:

I did not see force used regarding these people who were leaving the city. … I heard a number of accounts of that happening, that evening, as we connected with other foreigners who sought refuge in the French Embassy on the 17th. … There were some people who came in; most notably, some of the ethnic Pakistanis who lived here, many who went out on the highways, Highway 5 headed north, and two or three days later would be sent back to the embassy. They gave some of the first reports of killings out on the road; being forced out; the separation of families; and segregation into male/female. These were the first accounts that some of us journalists had heard of this. But on the day of the 17th, none of this was apparent to me in Phnom Penh.

An Attempt to Negotiate with the Khmer Rouge

Mr. Lysak moved on to discuss what Mr. Rockoff witnessed at the Ministry of Information, which he had alluded to in his testimony earlier. The prosecutor asked if the witness recalled hearing radio broadcasts regarding this. Mr. Rockoff replied:

I was told later that evening about the broadcast. I was not aware of it earlier. I am going by what we were told at the Japanese Bridge: we were told to go to the Ministry. But upon getting off the truck, the ride that was provided to us to go to the ministry, I could see to the right of the building maybe two dozen former government officials on the left, and to the right were some Khmer Rouge. One of the Lon Nol regime officers was discussing, trying to make a point or two to the Khmer Rouge. The Khmer Rouge were watching. One Khmer Rouge was taking a photo of the journalists getting off of the truck.

I had a camera hanging around my neck. I didn’t raise it to my eye. I had a wide angle lens. I took a photo just as a person came to grab my camera from me [and] took the camera, two cameras, camera bag. But I had just taken a photograph of the Ministry of Information, the Lon Nol regime – what was left of it – and the Khmer Rouge. After we were told to go to the French embassy, my camera bags were returned to me, with, of all things, the film intact. …

We were there about five minutes, maybe 10 minutes at the most. Sydney Schanberg through Dith Pran was talking to some people. And then a car came, driving up, and out of the car came the last Prime Minister, Long Boret, and his wife. They came over. There were a couple of Khmer Rouge with them. Guns were not pointed at them, but it was pretty obvious they were prisoners. Sydney Schanberg had a moment to talk with them. I wanted to get a photograph but not to lose my camera. They turned away and unfortunately, all I got was the backs of them as they walked to the car. A few minutes after, Long Boret was driven away.

We were told … we had to report to the French Embassy. On the way to the embassy was the Hotel Royal, and I stopped at the hotel to get my emergency survival kit.

Mr. Lysak showed the Chamber a short clip from the film Pol Pot: The Killing Embrace.[19] This clip, which appeared to be a video montage of black and white photographs, included photographs of:

- A child holding an M-16, which was one of Mr. Rockoff’s photos that had been discussed earlier.

- A man standing to the left with his hands up, wearing white, another in the middle, with his hands up, standing beside a Vespa, and what appeared to be the back of a soldier to the right.

Photo: Al Rockoff

- Two soldiers dressed in black entering a building, armed.

- Two dead bodies on the floor in a pool of blood with a woman and man watching the scene, sitting on stairs to the right of the bodies with the woman cradling the man.

- A wide-angle photograph of two large groups of men standing facing each other; to the left side, men standing with arms folded and dressed in slacks and white business shirts, some wearing ties; to right side, others dressed in dark clothing, one of whom appeared to be taking a photograph.

At this point, Mr. Rockoff confirmed that many of these photographs were taken by him. Mr. Lysak asked whether, in particular, Mr. Rockoff recognized the last photograph of the two groups of people. Mr. Rockoff confirmed that this was his photograph taken at the Ministry of Information, and those with their arms folded were the representatives of the Lon Nol regime “trying to bargain.”

Many of the Lon Nol officials “looked familiar,” Mr. Rockoff said, but he did not recognize any of them, as he was a photographer and did not interview people. Mr. Lysak sought to confirm whether Mr. Swain was also present at this time. Mr. Rockoff advised that the whole group of journalists abducted from Preah Ket Mealea Hospital were present at the Ministry of Information.

In Mr. Swain’s journal entry of 4 p.m. on April 17, Mr. Lysak quoted, he wrote, “There were 50 prisoners lined up in front of the building. They included Lon Non, Marshal Lon Nol’s younger brother. … There were several generals and Hou Hong Sim,[20] director of the cabinet of Long Boret.”[21] Mr. Lysak also read from Mr. Schanberg’s article “The City is Falling,” which stated:

When we arrived, about 50 prisoners were standing outside the building, among them, Lon Non, the younger brother of President Lon Nol, who went into exile on April 1, and Brigadier General Chim Chhuon, who was close to the former president. Other former cabinet members were also there, very nervous but trying to appear untroubled.[22]

Mr. Rockoff confirmed this refreshed his memory and was “informed later” about Lon Non’s presence there.

“A couple dozen” Khmer Rouge soldiers were “outside the building,” Mr. Rockoff went on. They were armed, although “many of them had pistols, not all of them had AK[-47]s.” At the time, he continued:

The Lon Nol regime official was discussing, making his points; emphasizing some points, with his right hand hitting the palm of his left hand. Any discussion between the two elements stopped as soon as the foreign elements were taken off the truck and we walked over there. Sydney Schanberg started talking to a Khmer … who was talking to him.

At this point, the photographic montage was replayed, and paused at 32 seconds, as requested by the prosecutor. This image was a detail of the photograph of the two groups of men, and focused on a man standing in front of the group of men on the right, dressed in dark clothing with akrama[23] around his neck and holding papers in his hand. Mr. Rockoff said that he did not see this person talking to the other group and that this was not the person to whom Mr. Schanberg had been speaking.

Mr. Lysak had the photographic montage paused at the 41-second mark. The video panned to the left of the photograph, to the groups of people dressed in business attire. Mr. Rockoff confirmed that one of these men was the one “trying to make a point” when the journalists approached.

Returning to Mr. Swain’s journal, the prosecutor read a further description of the scene at the Ministry of Information:

At the Information Ministry, a man in black, about 35 and clearly a leader, called through a bullhorn at the prisoners, dividing them into three groups: military, political, and ordinary civilians. The Khmer Rouge training their guns on them were tough, strong-looking, in jungle green, “Mao hats,” and the inevitable “Ho Chi Minh sandals.” Each one was a walking arsenal.[24]

The prosecutor asked whether Mr. Rockoff could see the Lon Nol representatives so divided. The witness denied this. As for the Lon Nol-regime Prime Minister Long Boret, the witness testified:

He did not surrender to the Khmer Rouge there. He was brought there by the Khmer Rouge. They took him at a prior location … but when he was brought to the Ministry, he was under their control. I could not see who was driving the car. He got out of the car, and then they took him away in the same car, maybe 20 minutes later, I’m not sure of the time frame. …

I don’t think any of us realized immediately after that what happened to them. We were told to leave for the French Embassy … They were taken away maybe north of us, but what happened to them we did not see.

Mr. Rockoff said he heard “that they were all marched to the Circle Sportif, which is the site of the current American Embassy, where they were all bludgeoned to death.” He could not say that they heard this “while still in Cambodia; it was much later.”

The prosecutor was permitted to show the witness a November 2, 1975, Bangkok Post article entitled “Executions Admitted.” This article included the following passage:

Deputy Cambodian Prime Minister Ieng Sary confirmed yesterday that two top leaders of the former Phnom Penh regime had been executed by the People’s Council after the Khmer Rouge victory. The confirmation by Ieng Sary that both former premier Long Boret and Lon Non, younger brother of former president Lon Nol, came after several unconfirmed reports earlier filtering out of that country.[25]

Asked whether he had seen this article, Mr. Rockoff denied this and explained it was difficult to read foreign newspapers in those days. However, he did confirm that he never saw Long Boret or Lon Non after the day at the Ministry of Information.

Moving back to his chronology, Mr. Rockoff described that what happened next as follows:

[At the Hotel le Phnom,] I picked up sort of an emergency survival kit: it had some vitamins, cans of food, a number of things in it. I was just going to take that with me to the French Embassy. Sydney Schanberg went to his room to get a few things … notes, a few other things. Then we walked north towards the French Embassy. It had just gotten dark. We were told to get to the French Embassy by 5 o’clock. We were late. … As we were marching towards the French Embassy, many, many hundreds of Khmer Rouge solders were marching single file down Monivong. … We get to the French Embassy and climbed over the wall. The wall was not very high; it was considerably less than the height of the wall now.[26] …Dith Pran relayed the order to Sydney and the rest of us: we had to go to the French Embassy. … That was the word given to us at the Ministry of Information.

Brief Discussion of Time Allocation

At this point, Mr. Lysak advised that he would require an additional 30 to 45 minutes to finish his questioning of Mr. Rockoff. For the civil party lawyers’ part, International Lead Co-Lawyer for the civil parties Elisabeth Simonneau Fort advised that no more than 45 minutes would be needed.

International Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Anta Guissé was given the floor. She advised that Mr. Samphan had “deployed significant effort” to participate in the hearings given the interest of this witness in light of his just being discharged from hospital. However, he was now having difficulty remaining seated in light of complications from his bronchitis. Therefore, he requested to follow the remainder of the proceedings from the holding cell. Mr. Lysak stipulated that OCP had no objection to that.

International Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Anta Guissé was given the floor. She advised that Mr. Samphan had “deployed significant effort” to participate in the hearings given the interest of this witness in light of his just being discharged from hospital. However, he was now having difficulty remaining seated in light of complications from his bronchitis. Therefore, he requested to follow the remainder of the proceedings from the holding cell. Mr. Lysak stipulated that OCP had no objection to that.

After a brief conference with his colleagues and in particular with Judge Silvia Cartwright, the president advised that he would grant additional time to both the OCP and the civil party lawyers in light of the interesting testimony Mr. Rockoff was providing. In addition, the Chamber granted the request for Mr. Samphan to continue his participation from his holding cell, provided he submit the appropriate waiver. The president then adjourned the hearings for lunch.

Witness’s Time at the French Embassy from April 17 Onwards

At the start of the first afternoon session, a new audience of villagers from Takeo took their seats in the public gallery. When the session commenced, Mr. Lysak directed the witness to his travel to the French Embassy and seeing many Khmer Rouge on one side of the road and civilians on the other side. He asked if the evacuees included “the elderly and sick.” Mr. Rockoff agreed this was so and explained:

As for April 17 early evening … [evacuees seen were] families, including elderly. As for the sick or infirm being kicked out of hospitals such as Calmette, I did not see that until the second day, looking out from the French Embassy. You would see in one case a patient being pushed on a gurney, people on crutches. The Calmette Hospital was being emptied … [although this could be seen] only to where we could see people headed north past the French Embassy. We could not see Calmette itself.

At this point, Mr. Lysak explained that part of the defense case was that the evacuation of Phnom Penh was in part a humanitarian operation responding to food shortages. He asked whether the witness ever saw the Khmer Rouge providing food to evacuees. Mr. Rockoff responded:

I did not see any assistance provided by the Khmer Rouge. As for assisting people with food, there was some provided to people in the French Embassy; vegetables [and] one pig a day which was butchered and had to feed quite a few people. But that was just what the Khmer Rouge allowed us to have. I had no idea concerning the provisioning of food.

Mr. Rockoff then advised, as he previously testified, that the Red Cross stationed at the Hotel le Phnom had to evacuate, along with everyone else. Vehicles were pushed, “as crazy as it may sound,” and arrived at the French Embassy at the same time as Mr. Rockoff. He did not see the Red Cross being ordered out of the Hotel le Phnom. Mr. Rockoff was only at the hotel for “15 minutes maybe,” but “they were leaving at the same time we were.”

From the embassy, Mr. Rockoff could see Khmer Rouge walking by the embassy, “usually in twos or threes.” He continued:

On occasion, the Khmer Rouge would come into the embassy. The French consular officials would insist on accompanying the Khmer Rouge whenever they came in. They searched for film. Also, Khmers were forced out. … One time, the Khmer Rouge came in, they were asking for cigarettes in sign language.

One time, I went out of the embassy with a Japanese journalist, Naoki Mabuchi … [through] a small hole in the wall covered in straw matting [for the servants to pass through]. I went to the lake Boeng Kak, the lake that used to be there … The Khmer Rouge that we were talking to, they wanted cigarettes. They were just smiling; they weren’t aggressive. I went back into the embassy to get my camera and I got into a little bit of trouble. They found out I left the embassy.

Color footage was then shown to the witness from the film Khmer Rouge: History of Genocide. It showed scenes including:

- A military truck with civilians milling around it;

- Foreigners distributing food to a group including foreigners and some people of Asian descent who may or may not have been Cambodians;

- A group of people of Asian descent talking to foreigners;

- Footage outside a window partially covered by Venetian blinds;

- Cambodian people looking despondent;

- Foreigners standing around a grassy field; and

- A man in a suit beginning to speak as if in a recorded interview.[27]

When asked, Mr. Rockoff confirmed that “those scenes were inside the French Embassy,” although he could not say if those events were after April 16 or 17. However, he could confirm that he saw “almost all of those people at the embassy,” although he could not recall their names. They included “some of the press and a few of the local foreign community.”

“A number of people were taking still photos or film, no video back then,” Mr. Rockoff said. If footage was shot, it may have been shot by Christoph Fröhder, he stated.

Mr. Lysak asked if the witness had heard whether there were negotiations between the embassy representatives and the Khmer Rouge. Mr. Rockoff agreed, noting, “It was relayed to us by certain journalists that there were talks going on and that the Khmer Rouge had permitted the embassy to have contact with the outside regarding this issue. But beyond that, I knew nothing else.”

This prompted Mr. Lysak to read to the witness from Mr. Swain’s 6 p.m. entry for April 18, in which he described a meeting convened by Paul Ignatieff, the United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) head in Phnom Penh, for all the internationals, including the “22 journalists in the camp compound, 15 members of the Red Cross, including the Scottish medical team, six United Nations officials, and a handful of other nationalities including Americans.” This meeting reported on progress that had been made “during two meetings with the Khmer Rouge authorities who called themselves the Comité de la Ville.”[28] Asked if he could recall such an authority, Mr. Rockoff denied this, and explained, “The meetings were not done in the area that most of the foreigners and the press stayed. … I was kept in the dark about a lot of this.”

As for whether the witness was aware that a number of Lon Nol officials had sought asylum in the embassy, the witness confirmed that he was aware that Sisowath Sirik Matak had attempted this, but he was not there at the time. However, he noted that there were a number of soldiers there, including a “soldier operated on by the International Red Cross, who was shot in the neck, and he died.” There were also at least 300 “minorities who came over the Mekong” there, who were military. Mr. Rockoff witnessed these people being “forced out.”

This prompted Mr. Lysak to read to the witness a telegram sent by the French consul, Jean Durack, on April 18, with the subject Political Asylum. In this telegram, Mr. Durack reported:

Following ultimatum from City Committee, I am compelled, in order to ensure the security of our compatriots, to include in the list of persons present at the embassy:

- Prince Sirik Matak and two of his officers.

- Princess Mam Manivan, of Lao origin, third wife of Prince Sihanouk, her daughter, her son-in-law, and her grandchildren.

- Mr. Oeung Bunhor,[29] president of the National Assembly.

- Mr. Lung Nol,[30] Minister of Health.

Barring express and immediate order from the department requesting me to grant political asylum, I will be compelled to turn these names in within 24 hours.[31]

Mr. Rockoff could not, however, recall the identities of these additional people who were reportedly at the embassy.

April 20, 1975: Expulsion of Cambodian Nationals

Moving on, Mr. Lysak asked Mr. Rockoff how many people were taking refuge at the embassy before April 18. Mr. Rockoff apologized and explained that “I could not hazard a guess.”

The prosecutor turned to consider the day on which Cambodian nationals were expelled from the embassy. First, asked for further details of their fate, Mr. Rockoff said:

It was kind of dark. It was cloudy, and there were a lot of tearful goodbyes between the Khmers who were leaving and those who were not. I’m sorry, I’m trying to recollect; it is very difficult. There were a few friends of mine in that group who went, and it wasn’t until years later that I heard reports about what happened to these people. Of the Cambodians who left the embassy and survived, there’s only one I know of. That would have been Dith Pran.

Mr. Lysak asked whether these people, like others, were to be evacuated. The witness replied:

Everyone headed north. The group of military and their families, I wasn’t sure for a long time, for years, what happened to them. I know that after they left, most of the people had passed out of sight, and there was a fair amount of gunfire just past the sports complex just north of the embassy. Some people thought they were just shooting at the clouds, to drive the rain away, because it was raining, it was very gloomy weather. But I’m told a few years later that there were people shot in the sports complex. Who, I don’t know.

As for when Prince Sirik Matak left the French Embassy, Mr. Rockoff said that he heard “nothing” at the time. He also noted that print journalists did not always share their information, including with photographers, so that he was “in the dark” until leaving Cambodia.

Returning to the witness’s previous mention of the presence of another “large group” of soldiers at the embassy, Mr. Lysak asked the witness for further information in this regard. Mr. Lysak asked whether these people were people known as FULRO (or the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races), Mr. Rockoff confirmed and described as follows:

Yes. Some of them were. Some of them had fought in Vietnam and were a lot of trouble in Vietnam, such as … Major Khe Pado,[32] who was with Vietnamese elements in Vietnam when the Montagnard revolt occurred. Because he had … shoved a bunch of Vietnamese Special Forces into a latrine and then chucked grenades in on them, he was under death sentence in absentia in Vietnam from the Saigon regime, so he fled to Cambodia and fit in perfectly with the other minorities living on the east side of the Mekong. …

His unit’s outpost was besieged by the Khmer Rouge for some weeks, and then he … came to Phnom Penh. He saw me. Because I had been out with his unit before, he recognized me. He told me how his compound, which was maybe 20 miles from Phnom Penh … the Khmer Rouge had encircled it. There were hundreds of Khmer Rouge passing nearby. … He managed to get his wife out. They escaped. He was covered in thousands of scratches and bug bites, you know, from the escape. Made it to the Hotel Royal where he saw me. … He took his people to the French Embassy.

Mr. Lysak sought clarification on which side the Montagnards had fought for in Cambodia. Mr. Rockoff replied, “They fought on the American side; they fought with the Vietnamese. … They worked very closely with the Americans.” There were a minority of FULRO among the soldiers in the embassy; “the rest were pure Khmer, and mixed through marriage. Pado himself had a “strong affinity with the Kampuchea Krom.”

On the day Cambodians and the people from the ethnic minorities were pushed out of the embassy, Mr. Rockoff recalled:

Pado and his wife, all their people were getting all their gold and their jewelry together. Took it off and put it in their bag. The Cambodian soldier who the Red Cross had been operating on had died. They had easily a kilo to two kilos of gold. They put it under [the] body [of the dead soldier,] and then put a grenade, wrapped tape around it, pulled the pin, like a booby trap. … The idea was, hide the gold; don’t let the Khmer Rouge get it. They were very calm despite the fact that they were probably sure that they were going to their doom. They were very calm, very quiet. I couldn’t believe it.

Witness’s Own Evacuation Out of Cambodia

Moving to his final subject of inquiry, Mr. Lysak asked the witness to describe how he managed to leave the French Embassy and travel out of Cambodia. The witness explained:

The foreigners were split into two groups. There was a first convoy that left, and the trucks came back a few days later to pick up the rest. [They were] Chinese trucks. There were 24 people per truck: two bench seats, six people sitting on each bench, and the other 12 standing up in the center. Whatever you had in the center, you could sit on. There was a driver, and the Khmer Rouge, and a French consular official watching us just as intently as the Khmer Rouge were.

The convoy of trucks left, headed south on Monivong, turned right to the airport. At the airport, there was a huge red banner flying. The truck went past the airport, some kilometers, then made a right turn and headed north. We went off paved roads onto trails; pretty well traveled trails. The convoy paralleled government roads fairly well, but off the main roads. [For example,] going up Highway 5, normally you would go with Oudong on the left; well this time, we were travelling with Oudong on the right, in the middle of nowhere. But [we were] making fairly decent time. What slowed us down was each time we got to the edge of each districts, the convoy would stop. The Khmer Rouge would go up ahead in a jeep, [and] get clearance for us to go through the next sector. So we spent a lot of time waiting, just sitting in place. It was a two and a half day trip to the border.

As they were evacuating, Mr. Rockoff described, he could see how Phnom Penh exhibited “striking changes: absence of people. Very few people. When you saw people, they were Khmer Rouge. You didn’t see families, didn’t see civilians.” He continued, “The only group of people I saw were Khmer Rouge. [It] looked like they were exercising by the train station; calisthenics. On the road to the airport, nothing, except for the occasional armed Khmer Rouge soldiers in twos or threes along the way, or at intersections.”

For his final question, Mr. Lysak asked Mr. Rockoff whether he witnessed any other provincial towns during his journey to the Cambodian-Thai border. Mr. Rockoff responded, “We overnighted at a [pagoda] in Battambang. We arrived at night and left before daybreak, so I have no visual impression of Battambang whatsoever.”

Witness Describes Acquaintance with Pol Pot’s Brother

At this point, Ms. Simonneau Fort took the floor, advising Mr. Rockoff that she had follow-up questions on some details and would relate not simply to Mr. Rockoff’s profession but to his experience living in Cambodia for two years. First, she turned to the period prior to April 1975 and asked Mr. Rockoff where else he travelled before 1975. Turning to the civil party lawyer and resting his blue-jeaned leg on his knee, Mr. Rockoff responded:

You have to realize the major highways were all cut by the Khmer Rouge. The army was always trying to open the highways, including Highway 4 to get to Kampong Speu. I have been there. I went to Siem Reap. … I was flown up in a Khmer Rouge plane because the Khmer Rouge always had the airport. …

If you wanted to go to a provincial capital, usually you had to get a ride with the Cambodian air force. Many of the places I went to aren’t cities; they were just roads, in the fields.

The civil party lawyer sought confirmation whether this meant that Mr. Rockoff only went to areas that were not Khmer Rouge-controlled. “I don’t think the Khmer Rouge would let me go with them,” the witness replied. However, he did see people fleeing areas occupied by the Khmer Rouge “many times.” Ms. Simonneau Fort asked what these people described. Mr. Rockoff said he was unable to question them, as “a lot of the interviews were done by refugee agents once they were directed to a camp. I would hear second, third-hand stories later on, but I did not have direct contact with the refugees.” He explained, “Phnom Penh was like a big refugee camp. In fact, the Cambodiana Hotel had 23,000 refugees in it.”

Asked what the “educated people” he was with would say about Khmer Rouge policy at the time, Mr. Rockoff said:

Two things that I heard repeatedly in the last month or so of the war was: when the war is over, everyone will go back to where they came from before the war. Since there were two million or so refugees in Phnom Penh who were not from Phnom Penh, that was probably good news for them. The other thing we heard a lot was that those Khmer who put a million dollars or more into the fund for the final offensive would have a place in the new Cambodia. I was told it was on their radio broadcast, it was part of the information that was being sent around. I don’t know if anyone was naïve enough to believe that, but that’s what was going around. But the one thing that a lot of people had no problem with was going back after the war.

Pressing the witness on this point, Ms. Simonneau Fort asked whether people said anything regarding the lifestyle of the Khmer Rouge and their policies. Mr. Rockoff denied any knowledge of this.

The civil party lawyer then asked if the witness was able to advise the Chamber of things that the witness may have heard refugees saying at the time. Mr. Rockoff said that he was not able to do so, as he was not the one who interviewed them. Ms. Simonneau Fort stressed that she also was referring to things that Mr. Rockoff heard secondhand. Mr. Rockoff explained that he did not hear anything of this nature, as his journalist friends would not tell him anything and would instead be more likely to ask him for information.

Moving on to a new topic, Ms. Simonneau Fort asked the witness whether he had heard anything about the buildup of the Khmer Rouge army, anything from his friends or entourage. “No,” Mr. Rockoff replied simply.

As to whether he heard of the impending evacuation, Mr. Rockoff replied:

Not exactly, although there was one Cambodian who worked in the Ministry of Information. He kept saying his brother would be here soon. … This guy’s name was Saloth Chhay. His brother’s name was Saloth Sar, also known as Pol Pot. He had no idea of the importance of his brother. It is my understanding he went missing out on Highway 5, like so many others.

Mr. Rockoff also did not hear any names of people who would become leaders of the Khmer Rouge as of April 17, 1975.

Shifting ahead to the witness’s testimony concerning the Preah Ket Mealea Hospital, Ms. Simonneau Fort asked whether the hospital was being evacuated when he arrived. Mr. Rockoff explained, “Some beds were occupied by the dead. [There were] bodies on the floor. You saw a photo earlier of a husband and wife lying dead on the floor and other Khmers sitting on the stairs looking at the bodies.”

As for the evacuation of families and the infirm, Ms. Simonneau Fort sought from the witness “a more precise picture” of their fate, including, for example, whether people carried personal effects, whether the Khmer Rouge provided any assistance, and what modes of transportation were used. Obliging, Mr. Rockoff said:

The evacuation was not accomplished in one day. It took a couple of days. But the sick and the infirm, the amputees, the patient on the gurney being wheeled down on the road, that was the second day, the 18th, that I saw that. I had no idea what was going on inside the hospital. …

There were families. If you saw elderly persons, children, a male and a female, I would have to assume that was the family. … Most were on foot. There were a few vehicles being pushed. The Khmer Rouge would let people pile things into a car. A lot of people would push the car, even if it had gas. But once you got north of Phnom Penh, you would lose the vehicle and all possessions inside it anyway. … It was mostly what you could carry.

Inside the embassy, did the Khmer Rouge provide any information via radio? Ms. Simonneau Fort asked. Mr. Rockoff said he had “no idea” about this; he did have a radio but he listened only to the BBC. Next, Mr. Rockoff advised, when asked, that “there was a core of journalists the embassy communicated through: Patrice de Beers, Sydney Schanberg, Jon Swain. The ‘A list’ of journalists.” Also, he added, the Khmer Rouge would come in from time to time to remove radio transmitters, leaving behind only simple radio receivers.

Ms. Simonneau Fort asked the witness whether he was given any specific reason for why the foreigners had to leave Phnom Penh. The witness denied this, but then noted that one day he heard a very strange reason. By way of explanation, Mr. Rockoff relayed the following anecdote:

After a few days, we saw an airplane circulating Phnom Penh. Four engine, commercial jet. It turned out that a third country had sold China two aircraft, violating what President Nixon wanted to do regarding no sales to China. So it had a big red tail on it. At the time, Northwest Orient Airline had a big red tail, so we thought, “Oh, they’re going to fly us out.” Then we looked at it a little closer [and saw] stars on the red. It must have landed at Pochentong. …

One of the Khmer Rouge representatives, along with a consular official, came to talk to us about food needs. One of the journalists asked him, “Are these planes going to take us out?” The guy tried to reassure us by saying, “They’re not for you. But you will be leaving. You will be leaving by road.” One of the journalists said, “Why? Why can’t we fly?” He said, “Because we want to show you what we have done.” Of course, the reality was they did not show us what they did. … The purpose of the two flights, I had no idea what they did. It just looked so strange. Two flights of an American aircraft: an American-made Chinese aircraft.

Finally, Ms. Simonneau Fort asked the witness what he saw, and what struck him, while traveling to the Cambodian-Thai border “just a few days following the fall of Phnom Penh.” The witness replied, with a clarification:

It was weeks after the rise to power of the Khmer Rouge, three weeks later. On the convoy out, we were not driven past any of the sites of killings, but if the wind was blowing right, you could smell it, way off in the distance: you could smell the bodies. But they were not going to show us what they did. We did not take any of the main highways out, such as Highway 5, where a lot of the atrocities occurred. We went on a road that paralleled some of the roads.

The Khmer Rouge had really tight control over what we would see. When we were in the [pagoda] in Battambang, you couldn’t see anything, you couldn’t see out. By the time it was daylight, it was outside the city, so I had no idea what was in Battambang.

With the civil party lawyers’ questioning concluded, the president adjourned the hearing for the mid-afternoon break.

Revisiting the Fate of Lon Nol Leaders at the Ministry of Information

At the start of the final session for the day, the floor was ceded to Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne, who advised that he had a few complementary questions to ask of the witness. He first focused on the event that occurred at the Ministry of Information. He asked Mr. Rockoff if this building still stands. The witness agreed, and stated, “It’s on the boulevard that goes from the train station to the river; the street that’s just north of Street 108.” This prompted the judge to note that all the events described today were in a specific parameter very close to the French Embassy. He asked the witness whether he was able to observe conditions in other parts of the city. Mr. Rockoff responded:

The area around the Independence Monument and a couple hundred meters south, that’s as far as I got on April 17. I had been much further south going towards Ta Khmau in the days prior to that, where there was massive evacuation of hundreds of thousands of people moving towards the center of Phnom Penh because of the shelling on the other side of the river, and the Khmer Rouge were approaching the bridge. On the 17th, as I said, … when I got a little ways south of Independence Monument, the Khmer Rouge soldiers headed north were really dirty, bad mood. I did not feel safe going any further south, so I turned around and went north.

At this point, the judge asked if the change in atmosphere was “abrupt.” The witness could not comment on this but noted that there was indeed a shift that was noticeable in the “large number of people” moving north near the Japanese Bridge. “The mood did change, but I would not say it was all of a sudden, everywhere. It was over a few hours,” he concluded.

The judge asked whether the witness ever heard about a person called Hem Keth Dara and the MONACIO (or Mouvement National) movement. Mr. Rockoff said, “I heard about this afterwards, sometime after leaving Cambodia, just through the writing of other journalists. They were considered phony Khmer Rouge, not genuine.” He explained, “They were easy to identify. They had good shoes on. Clothes were well-fitting. They were too clean, too healthy to have been out in the field.” He added that “none of these people were around by late afternoon” when the witness went to the Ministry of Information.

Mr. Rockoff then clarified that he went to the Ministry of Information “twice”: once in the morning when the Khmer Rouge were “rushing up the steps,” which he explained was clearly in the morning given the direction of the shadows in the photograph. The second trip was the one he was forced to make and he “assumed [this trip] was an arranged ride.”

As for whom the witness thought ordered his travel to the Ministry of Information on the second occasion, and whether it was the “superior Khmer Rouge” who ordered this or the “immediate guard,” Mr. Rockoff stated that he did not believe it would have been the former “because there were obviously higher ranking Khmer Rouge that they brought us to and who had control of us under the Japanese Bridge.”

Next, the judge requested to display an image from film Pol Pot: The Killing Embrace. In this image, two persons wearing black and holding machine guns could be seen entering a building.[33]Asked if he recognized the photograph, Mr. Rockoff confirmed that this was a photograph he had taken, and was the photograph he referred to as having been taken in the morning. Asked to describe the photograph, Mr. Rockoff said:

The person in a white shirt standing in the doorway may possibly have been an employee of that ministry. He was in there when they came in. Another thing I wanted to mention: one of the people running in to the ministry was barefoot. … This was not one of [the phony Khmer Rouge]. The phony Khmer Rouge were all healthy, had good shoes.

The judge showed the witness a similar image of the scene, but of very poor quality. The witness confirmed that it was his photograph, although it had been cropped and was a poor quality reproduction.

Turning to the witness’s previous mention of Pol Pot’s brother Saloth Chhay, the witness said that he never met Pol Pot himself and that “as with many families in the American civil war, many families were split up.” He continued, “I believe [Saloth Chhay] had no idea of the importance of his brother. To him, his brother was only a commander.” Mr. Rockoff could not, however, shed light on Mr. Chhay’s duties at the ministry where he worked.

The Fate of Individuals in the French Embassy

Judge Lavergne returned to the witness’s testimony of his time at the French Embassy seeking further details of separation of people in the embassy. He asked the witness specifically to discuss the fate of “mixed families,” that is, “one Cambodian parent and another parent of a different nationality.” Mr. Rockoff said that he had “no knowledge” of what happened outside the embassy, but within the embassy, he recalled:

One tragic case was a French woman with a Cambodian husband. The Khmer Rouge originally said he could not go, even though he had papers, they were married. … About 10, 15 minutes after he physically walked out of the embassy with other people, the Khmer Rouge changed their mind and said that he could stay, but it was too late for the woman and her children because he was gone.

There were people who had to leave just because they did not have any kind of proper documentation. There were some cases of people who were allowed to stay because they had false documents, some supplied by the French. They saved some lives.

As for whether anyone was nevertheless able to escape the Khmer Rouge watch and flee along with the foreigners, Mr. Rockoff said:

I’m sure that there was more than the one case I observed. I personally observed that on the truck I was on, the young Khmer Rouge was supposed to count the number of people on the truck. The Khmer Rouge was counting, counting, and he counted 25. This Frenchman, with his wife [or] girlfriend … he understood what was happening and jumped off the truck. The Khmer Rouge started counting again. Then he walked off the truck and got on another truck. The Frenchman then got back on again. So we had 25 people. Nobody ever counted again. That was one life that was saved by a trick.

The evacuation plan included “the East Germans,” Mr. Rockoff continued, who “were forced out of their embassy at gunpoint.” “Also,” he added wryly, “they had to give up their cases of gourmet food, paté, sausages, and put into the common food stock. They were very, very bitter.” However, the witness was unaware of any other diplomats that came in, as they did not stay in the chancellery building with him. He recalled the anger of the East Germans, he said, “because they flew in specifically for the victory.”

Next, the judge asked whether the Cambodians who had sought asylum within the French Embassy compound left voluntarily or by force. Mr. Rockoff said that there was an arrangement where the Khmer Rouge had to be accompanied by an official coming in to the compound, “but the threat of moving through the compound searching for illegals scared many people. So many people may have left thinking there was safety in numbers. … I cannot answer what may have motivated many of them, but there were threats, there was fear.”

Regarding Sisowath Sirik Matak, Mr. Rockoff was not present when he was forced out, he said, so could not provide further details about this incident.

The judge asked the witness for further details about the sports complex he had previously testified about. Mr. Rockoff stated that it was the one “north of the French Embassy.” The judge stated that this was likely the stadium known today as the “Old Stadium” and previously referred to as the Stade Lambert. As for the gunshots he heard, Mr. Rockoff said:

It is not unusual to fire up into the sky: chases away the bad weather. That happened often. But they weren’t shooting out into the sky. I couldn’t figure out what they were shooting at, except for the ominous thought that hundreds of Cambodians had just left the stadium, and then they were shooting.

Comments Concerning Photographs by the Witness Supplied by DC-Cam