Role of Khieu Samphan Revisited as Hospitalization of Nuon Chea Shortens Hearing Day

Interview with Khieu Samphan from the film Pol Pot and Khieu Samphan: Facing Genocide, as presented by the OCP.

Nuon Chea, one of the Case 002/1 co-accused and the alleged “Brother Number Two” in the Khmer Rouge regime, has been re-admitted to hospital after only recently being discharged. This will likely disrupt plans for further hearings at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) — including the scheduled testimony of journalist Elizabeth Becker — since Mr. Chea has refused to waive his rights to participate in any hearings except for today’s and one hearing this week featuring testimony from a civil party.

Indeed, Mr. Chea’s hospitalization shortened today’s hearing, with only a half-day of hearings possible. Hearings today featured the conclusion of a “document hearing” focusing on the Khmer Rouge-era role played by accused person Khieu Samphan. The Office of the Co-Prosecutors (OCP) concluded the final part of their document presentation, featuring Mr. Samphan’s own writings, and the civil party lawyers then gave a very brief presentation of additional documents.

Following this, and as is customary in the ECCC with hearings of this nature, all parties were then given an opportunity to present objections and replies concerning the documents presented. This session focused not only on the documents presented on Mr. Samphan but also those documents earlier presented with respect to the role of accused person Ieng Sary. However, as Mr. Chea will not waive his right to be present at document hearings concerning his alleged role during the Khmer Rouge regime, a separate document hearing in relation to him will need to take place on a later date.

Nuon Chea’s Readmission to Hospital Triggers Reassessment of Hearing Schedule

This morning’s proceedings took place before an audience of approximately 200 villagers from Kampong Thom province, many of whom appeared to have been born before the Democratic Kampuchea (DK) period. They began with Trial Chamber Greffier Duch Phary giving the daily attendance report. Mr. Phary noted that Mr. Chea was “absent due to health reasons,” while both Mr. Sary and Mr. Samphan were participating in the hearings from their respective holding cells due to health concerns.

At this juncture, the president asked International Co-Counsel for Nuon Chea Victor Koppe to advise whether Mr. Chea would be willing to waive his presence for the testimony of an upcoming witness and civil party. Mr. Koppe advised that while Mr. Chea had been released from hospital on Thursday, January 31, 2013, he was readmitted on Saturday, February 2. Since then, Mr. Chea had confirmed that he would waive his right to be present for only the civil party proposed, but not the witness.

Khieu Samphan’s Khmer Rouge-Era Role as Seen through His Own Writings

Taking the floor next was International Senior Assistant Co-Prosecutor Tarik Abdulhak. Continuing from two previous hearing days addressing Mr. Samphan’s role in the Khmer Rouge,[2]Mr. Abdulhak returned to the last topic addressed, namely Mr. Samphan’s own writings. Specifically, the prosecutor returned to Mr. Samphan’s book Considerations on the History of Cambodia. He first quoted the following passage:[3]

The evidence Philip Short provided about the Vietnamese having created the Khmer Rumdo movement, together with the evidence that other researchers have discovered, makes it clear that all of Pol Pot’s monitoring, following his 378 principle, of Chakry, Chhouk, Ya, and the other cadres who had operated with the Viet Minh, was correct. Thus, Philip Short was incorrect when he wrote, “The role of prison S-21 and the confessions was not primarily to provide information but rather to provide the proof of treason that they needed to arrest anyone they had already decided to arrest.” The policy of independence from Vietnam required the implementation of absolute policies inside the country.[4]

Mr. Abdulhak then highlighted a passage outlining Mr. Samphan’s views on Pol Pot’s use of confessions extracted from cadres, specifically Koy Thuon:

As I understand it, in these respects, there were three primarily themes that may have caught Pol Pot’s attention [from Koy Thuon’s confessions].

- These confessions may have led Pol Pot to believe even more that his arresting Ya was not wrong, and Ya may have been an individual that played an important role in the new party that they were setting up.

- But the issue that Pol Pot may have noted most of all was related to the confession of Koy Thuon, meaning Doeun of Office 870, having given information to Ya secret information from the Standing Committee on the matter regarding Vy and Lao, the secretary and deputy secretary in Ratanakiri. Aside from Doeun, no one had known this.[5]

Concerning Seou Vasy alias Doeun’s arrest and disappearance, Mr. Samphan said that:

There is some opinion that after Doeun’s arrest, I rose to become Office 870 chairman to replace him. In fact, that is untrue. I do not know whom the Standing Committee assigned to replace Doeun. As I have already said, secrecy was very firm at that time. Even inside the same unit, inside Office 870, there was still secrecy. I did not even want to know or hear what Doeun did or went … My wife … used to leave food for him to eat. Very frequently, he was not seen to come to eat. After a long time, we seemed to get used to this situation. Where Doeun went to and came from was not given any thought. So then, neither my wife nor I knew that he had been arrested. We thought even less about who they appointed in his place.

Next, the prosecutor highlighted some of Mr. Samphan’s comments concerning a distinction between the withdrawal of food from cooperatives by the CPK Center and the relationship with Vietnam.

Depriving the people of rice in order to transport rice to the state to meet quotas led to a great loss of life. In this, another question that arises is, was the Vietnamese sticking of their heads deep inside to stir up the CPK that appeared clearly in 1973 over or not during 1975 to 1978? Regardless, the turmoil at the time was an important factor that led many good cadres who had in the past been loyal to the cause, and had been active in combat, to turn to retreat instead. We should understand their hesitance facing this situation. But the many attempts by the Vietnamese Communist leaders and their ultimatum in May 1976 made Pol Pot and the CPK leadership reach the conclusion that “smashing the internal latch-doors,” door keepers for the Vietnamese, is the only way to keep Kampuchea alive. In a word, the issue was massively complicated.[6]

Concerning the forced evacuation of the cities, Mr. Samphan discussed the reasons for this while also seeming to critique the work of researchers on this issue:

They have made accusations against Pol Pot about the evacuation of people from Phnom Penh and the provincial towns, but in making those accusations, they did not think about the incredibly difficult and violence-filled situations that the young and immature state authority faced …

The thing that might have led to great danger for the young and immature state authority was the situation in which tens of thousands had already died, and there were people lying in wait to keep on killing one another like that. These were very favorable conditions for the CIA agents to conduct sabotage and join with the remnants of the former Lon Nol army that had clearly hidden weapons in the city and various locations throughout the country to create rebellion in Phnom Penh and in various locations around the country. The greatest danger was that this rebellion and turmoil would create the opportunity for Vietnam to easily intervene from the outside and seize Kampuchea back from Americans under the pretext of coming to rescue it. At the time, in actuality, like it or not, the CIA and the Vietnamese Communists were joining together to kill the state authority. This was the situation that the leaders of the Khmer Rouge were most worried about.[7]

Building on this, Mr. Samphan wrote that:

If the Vietnamese had liberated the south before Phnom Penh had ben liberated, there may have been major danger. Having outrun them once, after liberation, it was imperative to run again. There could be no hesitation. This is why Pol Pot saw the expansion of high-level cooperatives throughout the country had made the revolution in Kampuchea 30 years faster than the revolutions in China, North Korea, and Vietnam. …

Were it not for the organization of the cooperatives, Kampuchea would have to suffer all the consequences of the situation of Vietnam, including respecting the 1973 Paris Agreement between Vietnam and America. In late 1972 and early 1973, because of raising the level of the cooperatives … the Khmer Rouge were able to continue to struggle independently.[8]…

Expressed differently, in order to get dams and crisscrossing feeder canals to irrigate the Kampuchean countryside, when we wanted to sort out sufficient food quickly, when we wanted to escape poverty, when we wanted to modernize agriculture, when we wanted to lay the foundation to move in steps towards industrialization, we had to carry out Socialist revolution, and each of us in the organization and all of us had to fight to erase private ownership and equip ourselves and our units with “collective stance.” But to reach those goals, since the country had just emerged from a war a war of destruction and was facing the dangers of starvation and death, the first situation was to overcome the situation of incredible hardship that the young and immature state authorities had to face. So then, some coercion was required for a while: coercion to work in a situation of lacking everything, for both those who were used to it and those who were not, because time was very urgent.[9]

Reflecting on the DK movement and why he joined it, Mr. Samphan wrote:

It is my understanding that the DK movement played an important role during a period of our nation’s history that no one may scratch out and erase. If someone were to scratch out, erase or change it, the scratches or erasures could be seen. Why? Because it is clear that Saloth Sar [alias] Pol Pot sacrificed his life to fight the Americans and fight the Vietnamese Communists to defend the sovereignty of the nation, and both of them had tricky maneuvers to attack or confuse the forces of the nation and internal forces to go along with them.

In 1960, I, like the other “progressive intellectuals” had the profound objective of an independent economy as the foundation for the independence of my country and with a firm will, wanted to end the special privileges and corruption that had led to a handful but increasing number of people who did not know how to be embarrassed about the huge suffering of the people. I strived to fight with the means I had when I was a Member of Parliament, but I lost, and I was forced to flee Phnom Penh to save my life. I took shelter under the protection of a movement that according to some people whom I had known in Paris was striving towards similar goals but which used a different method that I could not. Now my views are still the same. They have not changed.[10]

Standing Committee Meetings “Like a Family Reunion,” with Joke Telling

Mr. Abdulhak turned to Mr. Samphan’s other publicly available book, Cambodia’s Recent History and the Reasons behind the Decisions I Made.[11]

During the Central Committee’s successive meetings, however, particularly during the first year, certain abuses were noticed and severely criticized. Directives were given to correct them. For example:

- Return to smaller cooperatives: they were easier to manage.

- Improve working conditions in the fields: the number of people sent to the fields was to match the number of mattocks, baskets or other tools. The other workers were to be allowed to rest in the village or do lighter work, such as making baskets.

- Establish a rest schedule, which was to be three days a month. During those three days, extra rations were to be provided.

- Technicians were to be recalled to run the factories in Phnom Penh, and a certain number of intellectuals were to be returned to the capital to participate in technical education projects, such as the creation of a vocational training school.[12]

Concerning meetings of the Standing Committee and views about Pol Pot as a leader, Mr. Samphan wrote that:

In a word, Pol Pot represented the historical leader who was never wrong when it came to making important decisions. Judging from what I saw during the expanded sessions of the permanent bureau,[13]however, nothing approaching fear was apparent during those meetings. Indeed, the meetings were informal. They were more like a family reunion. Members would often take time out to tell jokes. However, because everyone had great confidence in Pol Pot, they accepted most of the ideas and analyses without much discussion. Once, when a member of the Central Committee and later the permanent committee was arrested, the committee’s confidence in Pol Pot did not waiver. The members considered each disappearance as a separate case and probably, in the eyes of the insiders, justified.[14]

On accepting the role as president of the State Presidium and head of the DK’s formal state, Mr. Samphan remarked that:

The Khmer Rouge leaders accepted [the late King Father Norodom Sihanouk’s] resignation in April 1976, and the title of president of DK was handed over to me. Despite my embarrassment, I thought in my soul and conscience, I thought that had I refused the post, I would have been failing in my patriotic duty. All things considered, and seeing how the Vietnamese leaders were behaving between 1970 and 1975, I thought that the fears of the Communist Khmer leaders were legitimate, and I did not want to see the mobilized national force that they represented weakened.[15]

Arrests in Preah Vihear, which Mr. Samphan had known of, were discussed in the following manner in Mr. Samphan’s book:

Near the middle of 1978, I did hear of mass arrests and atrocities committed in Preah Vihear province. It was my wife who, in tears, told me of the atrocities committed against her brothers, her relatives, and many other innocent victims. But at that time, the liberation of victims and the arrest of the provincial secretary of the Party, led me to believe that the arrests were an isolated case.

Khieu Samphan’s Role at Office 870 Following Doeun’s Arrest

Moving at this point to a new type of document, Mr. Abdulhak presented a discussion between Mr. Sary and Khmer Rouge historian Stephen Heder on January 4, 1999. In the document recording this, Mr. Heder said that:

I pressed [Mr. Sary] to compare Khieu Samphan’s role with his own. He confirmed Khieu Samphan’s election to the Central Committee in 1976 and his later appointment to chairmanship of Office 870. He asserted that in the latter capacity, Khieu Samphan would have seen many more docs of a general nature than him, but not necessarily docs related to executions or torture. He insisted that Khieu Samphan had, like him, continued to believe that CPK cadres arrested were being “reeducated,” not executed.[16]

Another document also confirmed Mr. Samphan’s role in Office 870, he said, although they would not present this document, in line with the Chamber’s ruling that this document should be discussed during the upcoming testimony of an expert witness.[17]

A written record of interview with a witness, Ta Sot, also related to Mr. Samphan’s role at Office 870, Mr. Abdulhak said next.[18]Ta Sot is deceased, but the Court had also heard testimony of his wife Sa Siek.[19]Ta Sot had been a regimental commander with 500 soldiers under his command in the North Zone, in which capacity he participated in the attack on Phnom Penh. Ta Sot had testified that:

Pong controlled all offices of the As, such as K-1, K-2, K-3, K-4, and K-12. Pong was with Uncle Pol Pot before he made any decision. First he had to meet with Pol Pot. Pong then disseminated the order to other offices. Pong received the joint order from all uncles, such as Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, Khieu Samphan, Nuon Chea, in accordance with their expertise (tasks and directions). Pong managed along in all offices of the As. Pong used to meet with Khieu Samphan at K-3, and Khieu Samphan used to meet Pong at K-7. I saw that. Pong was the chief of Office 870 until he died in 1976.[20]…

I used to deliver the letters to the provinces, however I did not know what was written because the envelopes were sealed. Some letters were from Uncle Pol Pot, Uncle Nuon Chea, Uncle Khieu Samphan and Uncle Ieng Sary, but mostly the letters were coming from Uncle Nuon Chea and Pol Pot who had them sent to the designated zone chiefs. …

I used to deliver the letters from Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, [and] Khieu Samphan, to chief of Preah Vihear sector Man, chief of Siem Reap sector Sot, chief of Prey Veng zone Sao Phim, chief of Stung Treng sector Vy, chief of Kratie sector Thom, chief of Pursat sector Khieu (deceased), chief of Battambang sector Yim (deceased), chief of Kampot sector Ta Mok (deceased), chief of Kampong Speu sector Sy (deceased). I knew that the letters were sent to the chiefs of the regions, districts, and villages, but I did not deliver them.

The next document Mr. Abdulhak presented was a journal article by Khmer Rouge historian Ben Kiernan discussing the role of Mr. Samphan during the DK period, and a response to Mr. Samphan’s second mentioned book. In this article, Mr. Kiernan opined that:[21]

Like most Cambodians, Sihanouk has since seen everything, but unlike them, Samphan has learned little. Having taken to the jungle, he emerged 32 years later without much to add. Vainly discreet, he seems unaware how much documentation of the internal workings of his regime is now in the public domain. …

Samphan thinks people will believe that only patriotism kept him going, and that he accepted the job of head of state after the 1975 CPK victory only out of duty to his country.

It is astonishing that he pleads near-total ignorance of the genocide which occurred when he was head of state (1976 to 1979). He claims that rarely-specified “Khmer Rouge leaders” (not him) bore sole responsibility for those deeds and failed to keep him informed. For all DK’s crimes, which he is shocked (shocked!) to discover now, Samphan expects sympathy from the surviving victims.

Though based at CPK headquarters, for instance, Samphan claims he was “profoundly upset” by his Party’s forced evacuation of Phnom Penh on its fall in April 1975. While others like Hu Yun opposed it, Samphan calls the evacuation something “I was not expecting at all.” Meanwhile the CPK had forcibly collectivized the countryside. “Great was my surprise,” he claims, on learning this soon after the 1975 victory. Until then he could have been the sole Cambodian in the countryside unaware of its collectivization.

Documentary evidence belies Samphan’s claimed ignorance of high-level policy at every turn. He admits to full membership of the CPK Central Committee from 1976, but not of its powerful Standing Committee. He says he attended only “enlarged” Standing Committee meetings. However the extant minutes for 1975 to 76 record Samphan in attendance at 12 of 14 Standing Committee meetings (gatherings not “enlarged” by lesser invitees). Samphan indeed attended the CPK’s closed, high-level deliberations.

After the point when he now concedes learning of the urban deportations and rural collectivization, Party documents reveal not only Samphan’s important role in the regime, but his awareness of looming purges. On October 9, 1975, he attended the Standing Committee meeting at which it appointed itself as Cambodia’s secret government. The minutes rank Samphan fourth in the cabinet hierarchy, after Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, and Ieng Sary. At this closed meeting, Pol Pot targeted a general,

Chan Chakry: “We must pay attention to what he says, to see [if] he is a traitor who will deprive himself of any future.” Then, moving also against Chakry’s deputy, Pol Pot added: “we must be totally silent . . . we must watch their activities.”[22]

Samphan was not so quiet about the fate of Hu Nim, a leftist parliamentarian, who unlike Samphan, protested DK policies and was arrested in April 1977. Nim’s torturer reported:

“we whipped him four or five times to break his stand, before taking him to be stuffed with water.” Samphan may not have read that report, but knowing Nim was in danger, he stated on radio the next day: “We must wipe out the enemy . . . neatly and thoroughly . . . and suppress all stripes of enemy at all times.” On July 6, CPK security forces massacred Hu Nim and 126 others. Posing now as a victim, Samphan claims Nim as “my friend” and recoils at the “suffering in his soul and in his body, what a nightmare.” This performance cannot convince us of Samphan’s claimed “naïveté”—or that at the time he “was unaware even of the existence” of “massacres and crimes.”[23]

In Interview, Khieu Samphan Discusses Alleged Crimes, Pol Pot and S-21, Closes Prosecution’s Presentation

The final document in OCP’s presentation of documents concerning the role of Mr. Samphan was a six-minute long excerpt from the documentary film Pol Pot and Khieu Samphan: Facing Genocide in which the accused discussed alleged crimes which occurred in the DK period, his thoughts on Pol Pot, and S-21.[24]At the point where the clip began, an interviewer asked Mr. Samphan, in French, when he first knew of the magnitude of massacres. Mr. Samphan answered, also in French, that this was when he came back to Pailin in the end of 1998.

Regarding S-21, Mr. Samphan said with a smile that he knew only about this when he saw a film by Rithy Panh. Interspersed with pictures of people at S-21, Mr. Samphan said he was surprised about these killings. He did not know who killed these people, notably including children, and could not “imagine that it was Pol Pot who killed the children.” He challenged the interviewer to tell him about seeing Pol Pot killing children.

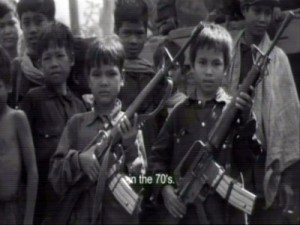

Still from the film Pol Pot and Khieu Samphan: Facing Genocide, as presented by the OCP.

Asked about children trained to be killers by the Khmer Rouge, Mr. Samphan said disdainfully, “Please, please,” and that “Cambodian street children in the 1970s … wanted to enlist in the army. … They were participating in the liberation of the country. They felt they wanted to do something to fight for social equality.”

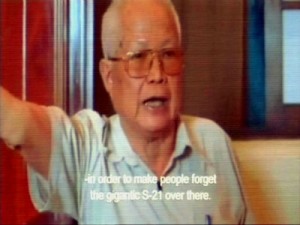

Advised that the youngest at S-21 was only 10 years old, Mr. Samphan did not express great surprise, and then added, waving his hand dramatically, that “a few youngsters” did not outweigh history. A lot of things still remained to be investigated, he said. Elaborating on this point, he said that:

You have to realize that without Pol Pot, without the Khmer Rouge … Cambodia would have been in the hands of the Vietnamese Communists. Now, if you please, don’t forget that. And what does it mean to be in the hands of the Vietnamese? What does it mean to us Cambodians? …

It wouldn’t have taken long for the whole of Cambodia to become a part of Vietnam. Millions of Cambodians live in south Vietnam today. Do you know how the Cambodians live in the south of Vietnam today? I’ll tell you. It’s an immense S-21. Isn’t it? So they talk about the little S-21 here so as to make people forget that gigantic S-21 over there in south Vietnam. It’s a very clever manipulation.

Interview with Khieu Samphan from the film Pol Pot and Khieu Samphan: Facing Genocide, as presented by the OCP.

Jabbing at his temple and gesturing into the air, Mr. Samphan said of Pol Pot:

They manipulate world opinion …. They demonize Pol Pot to make people forget the other side. They accuse him of being a dictator and use the word “genocide.” It’s not correct. A great leader of such a movement could not have acted like that. If so, he would never have created this movement. I’m going to shout that aloud at the trial.

There was then a shot of Mr. Samphan, wearing a wide-brimmed fisherman’s hat, walking slowly and deliberately through a restaurant and out into the nighttime air at the Phnom Penh riverside Sisowath Quay.

Civil Party Lawyers and Comments by the Defense

Next, International Lead Co-Lawyer for the civil parties Elisabeth Simonneau Fort advised that the civil party lawyers would only present their documents after these proceedings. She noted that the Chamber requested the civil party lawyers not to produce any documents for which the defense were not able to hear from the authors. Thus, she said, it would be logical to first hear all documents and testimony on the accused’s role and then the civil party lawyers would present their documents. A few civil parties, presumably yet to testify, would be speaking on the role of the accused. If these individuals were confronted by the defense teams, then the civil party lawyers felt it would then be appropriate to present their relevant documents.

The president stated, emphatically, that there seemed to be some confusion and that he had in fact given the civil party lawyers the floor in order to make any comments regarding the OCP’s presentation. The Chamber had already clearly understood the civil party lawyers’ proposal that they had been unable “to prepare documents on time,” but this was a different matter, he said. Ms. Simonneau Fort then clarified that the civil party lawyers had no such comments to make.

After this, the president ceded the floor to the defense teams for their comments. National Co-Counsel for Ieng Sary Ang Udom began by stating that his team reserved the right to make objections in relation to certain documents, presumably on Mr. Sary. His team would object to categories of documents, rather than documents themselves. In addition, and as he had already stated, he objected to the OCP’s presentation of the agreed facts and not just the role of Mr. Sary.

Finally, Mr. Udom objected to the OCP’s presentation of documents concerning deceased witnesses such as Ta Sot. He noted that Ta Sot’s wife testified that she had not heard anything from her husband about what he had done during the Khmer Rouge regime. The use of deceased person’s statements did not allow the defense to confront witnesses, and thus, such documents should not have been adduced.

International Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Anta Guissé took the floor. She advised that her comments related to the presentation on Mr. Samphan. She first stated that this stage was “rather delicate” as it was not the end of the proceedings, and there was a “fine line” between presentation of documents and a demonstration of their relevance, and pleading. This was an important point, she stressed.

In addition, she said, with respect to a letter signed by the late King Father Norodom Sihanouk, it was “regretful” that Mr. Abdulhak had “only at this particular stage” cited such a document, when Sihanouk’s testimony would have been “intriguing and interesting” while he had been alive. Second, she said, during hearings on the presentation of documents relevant to Mr. Samphan, it appeared that Mr. Abdulhak had circumvented some of the prevailing international procedures concerning his presentation of documents on trade and commerce. In particular, regarding the presentation of documents relating to prior witness Sar Kim LaMouth were questionable.[25]However, she said, she was unable to delve into this “given the restrictions of these proceedings.”

Certain documents’ full meaning could only be understood when supported by “direct evidence by their authors,” she went on. She also noted that Mr. Kiernan had expressed his disinclination to testify, which was a perplexing position given that several key documents were authored by him. Lastly, Ms. Guissé noted translation discrepancies in the document E3/165, concerning a speech given by Mr. Samphan. Ms. Guissé also noted that the English version of the document had not been translated by the ECCC but by the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam). This summary was entitled Document on the First Conference of the First Legislature of the People’s Representative Assembly of Kampuchea, April 11 to 13, 1976.

The ensuing discussion on this point was not entirely clear due to the frequent interchange between French, English and Khmer by the Khieu Samphan Defense Team and the consequent switching between several translation channels. The discussion began with Ms. Guissé handing the floor to her colleague, National Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Kong Sam Onn, to read into the record the relevant portion of this document in the original French. In the Khmer, Mr. Sam Onn said, page nine of the document clearly stated Mr. Samphan’s full title as the chair of dignitaries at that conference.[26]This same error appeared within the same document on another page, where the English version seemed to suggest that Mr. Samphan was the head of the State Presidium whereas the French suggested he was the president of the delegates.[27]Reference to the State Presidium, she stressed, was rather misleading, as it had “great impact on the meaning and relevance of these documents.”

International Deputy Co-Prosecutor William Smith rose to respond, but the floor was first given to Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne, who asked Ms. Guissé if this mistake had been notified to the Interpretation and Translation Unit for correction. She advised that they had not as they had been working with the English and Khmer versions for their preparation of the hearing, and only learned of the error during the hearing. Next, the judge asked whether any document articulated the precise role of the president of the delegates. Responding to this, Mr. Sam Onn said that the error in reference to Mr. Samphan’s role had been corrected in another paragraph of the same document, which referred to him as the chairman of the meeting.

At this juncture, the president advised Mr. Sam Onn to pause, as the DVD recording the proceedings had run out and needed to be changed. The president then took the opportunity to confer with the colleagues seated on either side of him, namely international Judge Silvia Cartwright and national Judge You Ottara. After some minutes, President Nonn then adjourned the hearings for the mid-morning break.

Following an extended break of 35 minutes instead of the usual 20 minutes, the Chamber reconvened. The president explained that the delayed start owed to “some issues with the recording equipment,” and the loss of some of Mr. Sam Onn’s response already given to Judge Lavergne’s question. Mr. Sam Onn duly reiterated his earlier statement concerning the translation error in the document Ms. Guissé had raised. He added that if the Chamber wished to know who made relevant announcements at that DK-era conference, it was incumbent on the OCP to adduce relevant evidence in this regard.

OCP’s Responses to Defense Comments

At this point, Mr. Smith rose to address Mr. Udom’s comments on the document presentation regarding Mr. Sary, which Mr. Smith had led.[28]Mr. Smith asserted that the purpose of this hearing was not to seek the admission of documents but to explain their content to the Chamber and the public. Importantly, the Ieng Sary Defense Team was unable to reserve their right to make later comments on categories of documents, as the Chamber had already decided.

Statements of deceased individuals such as Ta Sot were permitted, Mr. Smith argued, as the Chamber had decided. However, that statement was not made in the presentation about Mr. Sary, as Mr. Udom seemed to suggest. Moreover, the documents that the OCP had put forward were relevant. The documents supported five propositions suggested by the prosecution, namely:

- The positions Mr. Sary actually held in the DK.

- The level of authority Mr. Sary possessed in the Standing Committee and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- The participation of Mr. Sary in the SC and in the MoFA.

- Mr. Sary’s frequency of participation, suggesting the extent and scope of his role.

- The substance of Mr. Sary’s role and activities carried out in fact.

The prosecution argued that the probative value of these documents, taken together, was that Mr. Sary’s role was to “further the cause and participate in building a Socialist agrarian society at a rapid pace” and, as necessary, facilitate the killing of both internal and external enemies which might have obstructed this. The probative nature of the documents the OCP presented went to this, he said. The defense had decided not to address the probative nature of the documents, he noted, but in any case, this was the matter to be considered by the Chamber.

Next, Mr. Abdulhak gave OCP’s responses to comments on the Khieu Samphan document presentation he had given. First, he said that the defense counsel had incorrectly suggested that the OCP were only now referring to a letter by the late King Father Norodom Sihanouk. Instead, the OCP had already included this document in its 2010 Final Submission,[29]and in its Rule 80 document list. Respecting confidentiality, Mr. Abdulhak added, necessarily cryptically, that a document on the case file[30]made clear why the OCP had adopted the approach that it had concerning this document.

As for the documents on trade and commerce, Mr. Abdulhak noted he was uncertain what the comments referred to, but that he had already indicated he had presented documents selectively and there were several other documents in this regard. Regarding the witness Sar Kim LaMouth, the prosecutor recalled that Mr. Kim LaMouth’s testimony was that Van Rith had been subordinate to Mr. Samphan and Vorn Vet.

Regarding Mr. Kiernan’s writings, the OCP agreed with the defense that Mr. Kiernan should have testified, which the OCP had requested. However, the Chamber had decided against this. However, this did not render Mr. Kiernan’s writings inadmissible.

Finally, he said, regarding the document E3/165, which Ms. Guissé and Mr. Sam Onn had discussed at length, the OCP had not intended to impugn any statements which Mr. Samphan had made which he had not in fact made, and would join with the defense to request appropriate corrections. Having said that, Mr. Abdulhak noted that the defense had been on notice regarding the reliance upon this document since as early as September 2010, and that footnotes of the Closing Order had referenced this document (then-referenced as 13.13), including footnote 4771.[31]In addition, this speech seemed in no way inconsistent with other speeches reported to have been made by Mr. Samphan and with which the defense took no issue.

Next, the president invited additional comments from the defense. Ms. Guissé took the opportunity to respond to Mr. Smith’s discussion of probative value. Her team, she said, had been discussing relevance. Probative value, she stressed, could only be discussed at the end of the hearings. She entreated that parties not lose sight of the purpose of these document hearings.

Scheduling Arrangements in Light of Nuon Chea’s Hospitalization

Moving to a new issue, the president then noted that on January 18, 2013, Mr. Chea had waived his right to be present at the presentations concerning documents on the first and second movements of the population. However, Mr. Chea’s counsel later withdrew this waiver.[32]This prevented the Chamber from proceeding further with hearings on these matters.

Mr. Chea was returned to the ECCC detention facility on January 31, 2013, the president continued, with his treating physicians from the Khmer Soviet Friendship Hospital requesting that he rest for two weeks. That day, the Chamber had requested Mr. Chea’s counsel to report whether he would waive his presence for the testimony of one witness and one civil party. Mr. Chea was again admitted to hospital on February 2. The president then summarized Mr. Koppe’s advice of this morning that Mr. Chea agreed to waive his presence for the hearing of the civil party, but not the witness. The civil party would be available to testify on Thursday, February 7, 2013.

As for how Mr. Chea’s health issues impacted on upcoming scheduling, the president advised that the document presentation concerning Mr. Chea’s role during the Khmer Rouge regime would be deferred to a later date to be determined. The testimony of the civil party the president had just discussed would take place on February 7.

The president then adjourned for the day, at the earlier time of 11.45 a.m. Hearings in the ECCC will resume at 9 a.m. on Thursday, February 7, 2013, with the testimony of a civil party.