Walking in Slow Motion: French Priest Testifies on Civil War and Evacuation of Phnom Penh

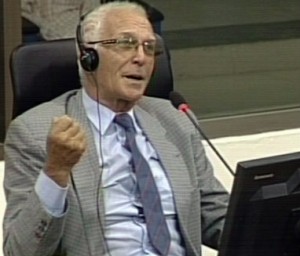

François Ponchaud, a French Catholic priest and author of Cambodia: Year Zero, gave emphatic and detailed testimony as proceedings continued in Case 002 at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Tuesday, April 9, 2013. He spoke about Cambodia during the civil war between 1970 and 1975, the evacuation of Phnom Penh after the city fell to the Khmer Rouge, and his movements and observations prior to leaving the country with other foreigners in early May 1975. Mr. Ponchaud, who has lived in Cambodia for over 40 years, testified in Khmer.

François Ponchaud, a French Catholic priest and author of Cambodia: Year Zero, gave emphatic and detailed testimony as proceedings continued in Case 002 at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Tuesday, April 9, 2013. He spoke about Cambodia during the civil war between 1970 and 1975, the evacuation of Phnom Penh after the city fell to the Khmer Rouge, and his movements and observations prior to leaving the country with other foreigners in early May 1975. Mr. Ponchaud, who has lived in Cambodia for over 40 years, testified in Khmer.

Over 200 Cham villagers from Borey Chulsa district in Takeo province attended the hearing. The co-accused Nuon Chea observed proceedings from a remote holding cell, due to his health concerns, while defendant Khieu Samphan was present in courtroom for the full hearing.

New Witness François Ponchaud Takes the Stand

Mr. Ponchaud, a Catholic priest, told the chamber that he was born near the Alps in France in 1939 and appeared to place his hand on a copy of the Holy Bible sitting on a small stack of books, when taking his oath. The witness said he had no relationship with either Nuon Chea or Khieu Samphan, but he met Khieu Samphan eight years before. Four years ago, former International Co-Investigating Judge Marcel Lemonde interviewed Mr. Ponchaud, the witness stated, and he reported to the United Nations Human Rights Committee in Geneva about Democratic Kampuchea on September 15, 1998. Mr. Ponchaud confirmed that he would testify in Khmer.

Trial Chamber Leads Questioning of François Ponchaud

Mr. Ponchaud told the chamber that he originally came to Cambodiaon November 4, 1965, during the reign of former King Norodom Sihanouk, lived through the Lon Nol regime, and had been in Cambodia for a total of 47 and a half years. The witness explained that he originally came to Cambodia with a Christian association that traveled to countries in Asia starting from 1959. He was selected to be part of the mission and spent three years studying the Khmer language and Buddhism and living with Cambodians to ascertain how Buddhism could help Christians and vice versa. President Nonn noted that Mr. Ponchaud had lived in Cambodia up until May 7, 1975, and inquired if he left Cambodia at any other point between arriving in 1965 and leaving in 1975. In response, Mr. Ponchaud stated that the French government sent two airplanes to evacuate French people from Cambodia in May 1975, and from July 1975 in France he began writing about what happened in Cambodia, the imposition of Khmer Rouge rule, and the misery of the revolution. He added that he also left Cambodia for one month in 1972.[2]

When asked to describe Cambodia between 1970 and 1975, Mr. Ponchaud told the court he was impressed by Cambodia’s development at the time, and though there were some injustices he did not pay much attention to them as he was young. He recalled hearing about then Prince Norodom Sihanouk cursing about Hu Nim and Hou Yunand the rebellion in Samlaut,[3]stating that he wanted to arrest Khieu Samphan,Hu Nim, and Hou Youn. The witness read about their supposed deaths before 1970 but learned later that the three had escaped. Mr. Ponchaud stated that in 1967, farmers in Samlaut revolted against Sihanouk because their land was being grabbed to be used for a sugar factory. The witness said he first heard about Khmer Rouge soldiers in 1968, including that they had killed people, and described how when he was south of Krauch Chhmar in Kratie province, he would hear dogs barking at night because the Khmer Rouge had come to the village to publicize their cause.

Mr. Ponchaud commented that he admired Khieu Samphan at the time because he was “Mr. Clean” and promoted by Sihanouk to head the Ministry of Commerce. The witness recounted that Khieu Samphan was offered bribes but did not accept them and was therefore an “admirable” and “good” person. “I learned that Samdech Sihanouk police undressed Khieu Samphan in front of the assembly and Khieu Samphan protested against the Prince, and he wrote about this in theL’Observateur,[4] and indeed we were worried that he would be arrested,” Mr. Ponchaud added.

President Nonn pressed Mr. Ponchaud about events in Phnom Penh as Khmer Rouge soldiers approached the city. The witness testified that he was in Kampong Cham province when Sihanouk was deposed in 1970 and heard that people traveled from Kratie province and Snuol[5]and Lon Nol soldiers dropped bombs on Skun to attack the demonstrators. The unarmed demonstrators came toChhroy Changvaron March 30 and Lon Nol soldiers opened fire,[6] killing 60 of them, he added. “The Khmer Rouge were cruel, but I believe that they were cruel because they had reason to do that, as they were not pleased with the way they were treated by the Lon Nol soldiers, and that time the Vietnamese troops were invading the border area of Cambodia,” Mr. Ponchaud said.

Witness Describes Behavior of U.S. and Vietnamese Troops

Mr. Ponchaud recounted being arrested by the Vietnamese at Angchey Mountain in Kampong Cham and having to pay 44,000 Vietnamese dong for his release. He stated that American soldiers and South Vietnamese troops invaded Cambodia on May 1, 1970, coming 40 kilometers inside the country. At the time, Mr. Ponchaud said, he was living in O’Raing Ov district in Kampong Cham and Vietnamese troops came to Sayang village. Mr. Ponchaud told the court:

The American and the Vietnamese troops were very brutal. They killed civilians and raped them. The only way the people could be safe was to join or to reach the Khmer Rouge soldiers. I could also refer to witnesses who say that the Khmer Rouge soldiers were very nice and good people. They helped us cultivate rice and also they were engaged in this assistance all along. It happened during the time when Cambodia was bombarded by the Americans. I am talking about this because I have my own version about the Khmer Rouge. At the beginning, Khmer Rouge provided some form of hope for the people of Cambodia. Even I myself in my book Cambodge: Année Zéro, I also wrote that I would pray that the Khmer Rouge soldiers came because people lost all hope during the Lon Nol regime. Cambodian people had to suffer greatly and in despair, and by 1973 we already knew what the Khmer Rouge had been doing. They were helping us in the fields.

Mr. Ponchaud continued that they learned people were evacuated in 1973 in Bos Knau[7] and Damnak Chang Eou[8]and information about the Khmer Rouge’s “bad deeds” intensified – perhaps due to battle tactics – but they were still convinced that the Khmer Rouge were not bad people and they treated people better than Lon Nol soldiers did. “When they won the war, we expected that they would lessen their cruelty,” he said, noting that the population was evacuated from cities from April 17, 1975, after the Khmer Rouge achieved victory.

At this point, Mr. Ponchaud argued that Henry Kissinger should stand trial for his acts during this period. He elaborated on this comment by describing U.S. bombing of Cambodia in the 1970s:

The Americans dropped bombs all across Cambodia, and I … bore witness to these events. I was in a house near the market of Kandal.[9] … At night I could see that the bombs were dropped in the horizon. It was like the skyline was burning. The American soldiers mistreated Cambodian people without any reason whatsoever. They killed Cambodian people through bombings. Some researchers say that about 100,000 Cambodian people died. To me, about 400,000 people could have been killed by the bombs. People were shivering – they were terrified and traumatized by these carpet bombings. We all know that everyone was having a very difficult time during the time of the bombing, and people in the paddy fields had to run to the city to take refuge. They were afraid of the Americans, who kept bombing them. So by April 1975, people already came to the city, and then we were informed or asked to leave the city because they said that Americans would be bombing us again. As I told you we had been traumatized by the bombings, so by way of hearing that we had to leave the city otherwise we would be bombed again, people were convinced and we had to leave the city. I talked to the Khmer Rouge that I did not want to leave Cambodia, I would like to live in Cambodia until I die, but the Khmer Rouge told me that I could be on my own and if I did not want to leave Cambodia, then I would have to be responsible for my own safety.

When pressed on whether he could see the bombing from his residence in Phnom Penh, Mr. Ponchaud said he believed the bombs were dropped close to the city because he could see the bright skyline, which was illuminated by fireballs from the bombs, he could hear the sounds of bombs, and the ground sometimes shook.

Mr. Ponchaud testified that he worked with refugees and observed people coming into the city everyday, estimating that two to three million people were in Phnom Penh at that time, some of whom were living in pagodas and on street corners. He said life in Phnom Penh was “miserable” and “chaotic” at the time; people did not have enough to eat and his organization could provide only minimal assistance until January 1975, after which it became clear that the city would soon be captured. Two days after January 1, 1975, Mr. Ponchaud recalled that Khmer Rouge soldiers crossed the Mekong River and food could therefore no longer be shipped from Vietnam. The U.S. was dropping food from airplanes via Bangkok, he added, but the parachutes repeatedly landed in areas conquered by the Khmer Rouge. The witness told the court he did not go to any hospitals, but he transported some sick people to a center to prevent their diseases from spreading.

Just Prior to the Fall of Phnom Penh

Under questioning from President Nonn, Mr. Ponchaud testified that from April 13, 1975, he believed Phnom Penh would soon be captured and stayed at a commune office where there was a tall church, which the Khmer Rouge eventually destroyed; he saw the Khmer Rouge marching into the city and burning some houses. Mr. Ponchaud explained that he was asked to help translate in French and Khmer and disarm officials at a refugee center set up by the head of the Red Cross at Hotel le Phnom,[10] stating that he felt bad for taking away items like knives because people needed them to cut food. The witness told the court that he heard fighting and gunfire around Phnom Penh and saw seven people dead near his residence after a bomb was dropped. “From 1973 onwards, the situation in Phnom Penh was so miserable, was so difficult, there was no food, and Khmer continued fighting and open[ing] fire,” he said, adding that in 1972 the Khmer Rouge also bombed at Tuol Svay Prey,[11] killing 200 people.

On the night of April 16, Mr. Ponchaud continued, he was at Hotel le Phnom disarming government officials taking refuge there, and later he went to the municipality, where he observed hundreds of people entering the city from all directions. He observed a packed white Sedan in front of the French embassy, and believed that French officials would be negotiating with the Khmer Rouge to ensure their safety. Mr. Ponchaud said tanks rolled into the city, firing shells, and he observed some youths wearing black clothes and holding flags, whom he claimed were mistakenly identified by journalists as Khmer Rouge soldiers.[12] By 10 o’clock,[13] the city was captured, the witness recalled. “At the beginning, we saw only young people searching others for weapons, but then we learned that they were the Khmer Rouge soldiers, and we learned also that the Lon Nol soldiers had to surrender, and the representative of the Lon Nol soldiers made it clear that the Lon Nol soldiers now were defeated and they surrendered,” Mr. Ponchaud recalled.

So by 10 o’clock, Phnom Penh was fully captured, and it was completely silent. There was no more gunfire. I did not believe that the Khmer Rouge stopped killing people but did not hear any more gunshots, and at 11 o’clock I saw the unspeakable event. I saw the sick people, I saw the crippled, who were crawling like worms right in front of my house and people were moving out of the city. And one of the handicapped asked to stay in our house and I said sorry, you have to move on, otherwise you would be killed if you stayed here. So we did not receive any patients and it was shameful for me not to do that, but we had no choice, and a lot of injured people were asked to move to the paddy fields. And I heard people said if the injured people did not want to leave then they would be killed by bombs, by the soldiers.

The witness continued to describe the evacuation, stating that the Khmer Rouge evacuated Cham Muslims and he was pleased because he thought they could return to their hometowns. At around 2 o’clock, Khmer Rouge soldiers in black clothes ordered people to leave due to fears of bombing, Mr. Ponchaud recounted, which people obeyed because they were frightened of potential U.S. bombardment:

I saw people walking along the street; they were marching out of the city. They walked in slow motion. I saw people march along the street, but the movement was very slow – they could actually travel on foot around three to four kilometers per hour. And then at around 6, I did not see any people in Phnom Penh, at least in my place I did not see any civilians.

Mr. Ponchaud described the Khmer Rouge soldiers as “indirectly” threatening people. “I and my friend met with the Khmer Rouge and I look into the Khmer Rouge eyes and they looked at us with a strange look,” the witness said. “Actually the Khmer Rouge could threaten us by only a bare look of eyes. They were very fierce.” On the night of April 17, there were military groups of around 10 members that had leaders, deputy leaders, and members, and one such group came to his house, Mr. Ponchaud recollected, telling them not to move around freely. The witness said he talked to the young soldiers who wished to learn how to drive their cars and described the cadres as ignorant because they blamed the car after crashing it into a tree. Then on April 18, Mr. Ponchaud testified that he drove the Khmer Rouge around, pointing out various landmarks and residences in Phnom Penh to them. He stated the Khmer Rouge cadres were not afraid of the Lon Nol troops but kept asking where American soldiers were staying. “The Khmer Rouge thought that there was the presence of American soldiers everywhere,” he said, adding that he did not see any civilians while he drove but the Khmer Rouge had broken down their doors and taken their property. Mr. Ponchaud told the court he later went to the French embassy.

Mr. Ponchaud recalled that the Khmer Rouge announced to city dwellers:

Comrades, leave Phnom Penh city as soon as you can, because the American soldiers will bombard the city. You will leave the city for about three or four days. You do not have to bring anything along with you. You only leave for a short period of time. You will come back. The Khmer Rouge soldiers are not [thieves]; your properties will not be stolen, so just leave the city as soon as you can.

The witness explained that after seeing different groups of Khmer Rouge soldiers in different colored clothes and weaponry, he believed they were “anarchic” and disorganized. Mr. Ponchaud testified that people had to leave in various directions depending on their residential area and he remembered a crying 12-year-old boy who wanted to go to his pregnant mother but was unable to. “People … were very sad and they were very depressed,” he told the court. “They were sadder than sad, and they did not want to leave because they noticed that the way the Khmer Rouge actually exerted pressure on us not only through weapons but also through the eyes as well.” The witness stated that he did not recall or personally witness the Khmer Rouge physically coercing people to leave or killing anyone but that they exerted psychological pressure on people. He added that the city dwellers considered April 17, 1975, a peaceful day and believed the Khmer Rouge were not bad and would not kill their own people, so they obeyed their orders. Mr. Ponchaud explained that he did not see any corpses along the road, but he saw people walking along and people were treated badly:

It was beyond imagination because it was a brutal act by the Khmer Rouge towards the people, the evacuees. I had to leave the French embassy on two occasions. A few days later, perhaps on April 21 or 22, I had to leave the French embassy so that I could monitor the actual situation and I saw the Khmer Rouge occupied the municipality and I could not see other people other than the Khmer Rouge soldiers. And later on I met a Khmer Rouge female soldier; I was very frightened because women soldiers of the Khmer Rouge were believed to be even crueler than their male counterparts. The Khmer Rouge then evacuated or gathered the French citizens and those who were holding French passports. In the vicinity of Phnom Penh, it was empty, but I saw hundreds of people gather at Prek Phnou[14] but I never saw any dead bodies. I couldn’t say that people did not die during the course of evacuation, but I just didn’t see any.

President Nonn recounted that Mr. Ponchaud told the court he took refuge in the French embassy, before traveling along National Road 5 to search for his friends – Christian foreign nationals – in hopes of bringing them back to the embassy. In response to questions about this trip, Mr. Ponchaud responded that he traveled to Prek Phnou five or six days after April 17 with two Khmer Rouge soldiers and another French national – a teacher. He saw “seas of people” in rice paddies upon arrival, but he saw no soldiers, civilians, or dead bodies along the way. Mr. Ponchaud explained that he did not leave his car at Prek Phnou because he was terrified as there were Khmer Rouge soldiers carrying rifles. “I saw people whom I knew before,” he recalled. “I dare not even talk to them. I only actually signalled them through my eyes. We used our eye contact to communicate.”

Situation at the French Embassy after Khmer Rouge Captured Phnom Penh

Under questioning about the living situation and people at the French embassy, Mr. Ponchaud testified that there were about 500 foreigners – Americans, including people from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and a Laotian[15] – and around 500 Cambodians, the majority of whom were soldiers from the defeated Lon Nol regime. On April 18 and 19, Mr. Ponchaud recalled, they spoke to military personnel who wished to seek refuge in the embassy and on April 20, an elderly soldier called a meeting where he announced that Khieu Samphan wished to meet comrades at the French embassy in order to “rearrange the revolution.” The witness detailed how Cambodian women married to French men could stay at the embassy but Cambodian men married to French women had to leave to work with the Cambodian population. Mr. Ponchaud told the court:

Under questioning about the living situation and people at the French embassy, Mr. Ponchaud testified that there were about 500 foreigners – Americans, including people from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and a Laotian[15] – and around 500 Cambodians, the majority of whom were soldiers from the defeated Lon Nol regime. On April 18 and 19, Mr. Ponchaud recalled, they spoke to military personnel who wished to seek refuge in the embassy and on April 20, an elderly soldier called a meeting where he announced that Khieu Samphan wished to meet comrades at the French embassy in order to “rearrange the revolution.” The witness detailed how Cambodian women married to French men could stay at the embassy but Cambodian men married to French women had to leave to work with the Cambodian population. Mr. Ponchaud told the court:

On April 20 the situation was depressing because around 25 Cambodian men who married to French ladies, they were separated; they had to leave the French embassy. There was one French lady who is very young, and her husband was a former nurse at Calmette Hospital. She refused to stay in the French embassy. She refused to be separated from her husband, so she had to accompany her husband. She decided to leave the French embassy, and then one of them said, next year, or in one year’s time, we would see each other in Champs Elysées. I could not recall the name of that person, but on April 20 it was the hardest day of their life because they were separated from their loved ones.

Mr. Ponchaud recalled hearing that Angkar separated soldiers from civilians and he knew that some of the soldiers and army commanders were killed. On April 19, he continued, soldiers outside the French embassy demanded that the embassy hand over the “seven super traitors”[16] and they wished to protest, but AK-47s were pointed at them. Mr. Ponchaud testified that they had to choice but to hand them over and did not know their eventual fate, but he later heard from others that the Khmer Rouge executed them.

The witness informed the court that on May 7, 1975, he traveled along National Road 4 to Ang Snuol,[17] then to Uddong and Omleang,[18] then to Kampong Chhnang province where the Khmer Rouge were friendly and supplied them with food. Later, they traveled to Pursat province, where they changed trucks and went to Battambang province. They waited for a few hours before traveling overnight and arriving in Poipet on the Thai-Cambodian border at about 6 a.m., he added. “All the way I did not see a single person, when we thought that we were leaving from a ghost country,” Mr. Ponchaud said, repeating that he did not see any corpses.

President Nonn inquired how many couples were separated at the French embassy and how they left the compound. Mr. Ponchaud replied that he did not see the so-called “seven super traitors” because FrançoisBizot[19] was standing at the embassy gate and he only heard that they had been asked to leave. However, he told the court that the Cambodian men with French wives had to leave with Cambodian civilians. Mr. Ponchaud recalled that he had previously told Cambodians inside the embassy to leave before the Khmer Rouge came to retrieve them. People were eventually taken from the embassy to somewhere near the old stadium[20] and he heard that some people were killed at the stadium, he added.

Moving back to the “seven traitors,” President Nonn inquired which embassy councillor Sirik Matak had spoken to. Mr. Ponchaud described how he was the councillor’s personal interpreter and France did not have clear diplomatic relations with the Lon Nol regime around that time after withdrawing their ambassador. He stated that the French wished to recognize the Khmer Rouge because the regime was supported by then Prince Sihanouk, but at the time there was a chargé d’affaires and a councillor, who was later demoted to the position of vice-councillor. They were waiting for the Khmer Rouge to raise diplomatic relations back to the ambassador level, Mr. Ponchaud testified. He added that they wanted to negotiate for people to stay, but the Khmer Rouge were not prepared to do this. When asked about the people staying at the French embassy, Mr. Ponchaud said there was a mixture of nationalities, including a Laotian, some South Vietnamese, Americans – particularly journalists and CIA staff – and the Khmer Rouge were surprisingly quite courteous to foreigners, perhaps because they did not want to mistreat them.”They were courteous in the ways the Khmer Rouge considered to be courteous at that time,” he added.

Mr. Ponchaud explained that besides the French embassy, there was a Soviet Embassy, with staff who flew in to Phnom Penh on April 16. They put up a plaque that read, “We are Communist brotherhood,”[21] he said. The witness testified that there was a French couple who believed strongly in Communism who were told by the Khmer Rouge that they were not revolutionaries and threatened.

Evacuation of Foreigners from French Embassy

Mr. Ponchaud said there were about 500 Cambodians and foreigners left at the embassy after various people were made to leave. He described how on April 30, a first wave of foreigners left the embassy, followed by another – including himself – on May 7, and then another around May 23 or 24.[22] Mr. Ponchaud explained that FrançoisBizot negotiated with the Khmer Rouge and the French government agreed to prepare airplanes to transport foreigners out of the embassy, which angered the Khmer Rouge because the planes were an “imperialist” means of transport. As such, foreigners were taken by trucks starting on April 30 with those who were especially vulnerable, such as CIA leaders, pregnant women, and elderly people, he said. Mr. Ponchaud recalled fears that this first group of people had been killed after they did not hear any information for a couple of days, but they were later informed that the group had reached Poipet. He described his surprise that the Khmer Rouge did not ask questions or check passports when they left on May 7, as he had previous experience with communist authorities in Vietnam and China who had checked everything.

Mr. Ponchaud confirmed that he was among the last group of foreigners sent from the French embassy and had to leave the embassy key with Comrade Nhem, head of the division in the eastern part of Phnom Penh. “Comrade Nhem told me to leave Phnom Penh for Paris, and after the country had been cleaned, he said he would warmly welcome me back,” the witness added. Mr. Ponchaud explained that the foreigners had wanted to travel on foot to observe the situation in the countryside but were not permitted to do so and instead had to take trucks accompanied by Khmer Rouge soldiers. “A man on the truck told me although he was a soldier, he said he would like to go to France as well, and I could tell from that moment that even a cadre from the Khmer Rouge clique also was afraid of their own people,” Mr Ponchaud said, clarifying that he did not recall exactly if he left Phnom Penh on May 7 or reached the border on that date, but he was allowed to leave the country quite easily.

In response to questions from President Nonn about negotiations at the time, Mr. Ponchaud emphasized that there were no negotiations as the Khmer Rouge were the victors and did not allow it.[23]

Trial Chamber Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne Questions François Ponchaud

Firstly, the witness confirmed to Trial Chamber Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne that he was conscripted to join the French army when he was 20 years old and served in a paratrooper unit in Algeria for two and a half years, where he started to “hate war” because of its destructiveness.

Judge Lavergne requested further information about Mr. Ponchaud’s whereabouts in Cambodia prior to the Khmer Rouge period, to which the witness replied that he lived in Chhroy Changvar, then went to the countryside to live with peasants for two months before coming back to Phnom Penh in September 1966. Later, Mr. Ponchaud stated, he went to Kampong Cham province to continue learning Khmer and heard the Americans bombing the Ho Chi Minh Trial – roughly 80 to 100 kilometers away – when he was in Stung Treng.[24]

“About one million tons of bombs were dropped and Mr. [Henry] Kissinger, according to the documents we read that were exposed in public … last year, [] asked Nixon to use an atomic bomb to destroy and block the Ho Chi Minh Trial,” he stated.[25] Mr. Ponchaud testified that from 1965 Sihanouk permitted Chinese and Soviet weaponry to be transported to the port of Sihanoukville, and from Sihanoukville to Neak Loeung[26] and Stung Treng. “I saw truckloads of weapons being transported from Neak Loeung to Svay Rieng [province], from Neak Loeung to Memut,[27] and from Neak Loeung to Stung Treng and I on one occasion saw an overturned truck filled with weapons,” Mr. Ponchaud said, adding that he also saw North Vietnamese soldiers.

When Judge Lavergne pressed for more detail on his whereabouts, Mr. Ponchaud told the court that he traveled to Battambang province to communicate with Christian communities and was later asked to go to Kdol Leu,[28] then to Kampong Cham where he remained until war broke out after Sihanouk was deposed in March 1970. Mr. Ponchaud said hundreds of people traveling from Kampong Cham to Phnom Penh on March 19 were executed by Lon Nol soldiers, who also killed innocent, unarmed Vietnamese civilians. At the time, people listened to Prince Sihanouk’s speech from Peking appealing to Cambodian people to enter the maquis jungle, Mr. Ponchaud testified. The witness said that at the time he was fired at and warned not to return to Kampong Cham or he would eventually be killed.[29]

Judge Lavergne sought clarification that Mr. Ponchaud arrived in Battambang in 1967, then went to Kampong Cham and eventually left the province in 1970. He appeared to receive confirmation of these details from the witness. Then Judge Lavergne asked Mr. Ponchaud if he was translating the Bible into Khmer when he returned to Phnom Penh, and if so, for what purpose. The witness replied that he received about 50 students from the countryside who had nowhere to stay in the city and translated the Bible into Khmer because he believed that if they were expelled from the country they could leave behind materials for Christians. After Mr. Ponchaud briefly switched to French to explain that he translated documents for the Christian community to use if the mission was not present, Judge Lavergne requested that he avoid changes in language.

Under questioning from Judge Lavergne about whether people felt hopeful after the coup d’état, Mr. Ponchaud responded that some people did not support the leaders and some disliked Sihanouk,[30] with one teacher he knew buying a can of beer to toast the end of Sihanouk’s reign. “They celebrated when Norodom Sihanouk was toppled down and the situation was changing,” he added. “Peasants from the beginning supported Prince Norodom Sihanouk, but intellectuals in Phnom Penh, the majority of them didn’t support him.”

When asked if this difference set the city and countryside apart, Mr. Ponchaud stated that in 1623 Annam[31] took control of Prey Nokor – or Saigon – when Annamese and Siamese soldiers were fighting in Cambodian territory, at which point there were no cities in Cambodia as there were during the French colonial period. The witness said the Khmer Rouge followed Marxist-Leninist lines, wanting to “eliminate the city” and make the country equal.[32]

Witness Questioned on Pre-1975 Period

Judge Lavergne asked the witness about the Khmer Rouge’s treatment of people prior to 1975, to which Mr. Ponchaud stated that when Khmer Rouge soldiers captured a village in 1973, they set houses on fire, executed commune chiefs, and evacuated people to the forest. He added that in 1973, he knew people in Kampong Thom province – there were Christians there – which was attacked by Lon Nol soldiers. “We should also be aware that in 1973, in order to forgive the Khmer Rouge, the lower level cooperatives were established so that people could work in cooperatives to produce rice for the population,” he said.[33] On corruption during this period, Mr. Ponchaud testified that a Battambang governor sold rice to the Khmer Rouge and Sosthene Fernandez sold weapons. “The Lon Nol government finally would be defeated because of this; however corruption in Lon Nol regime was less than these days’ corruption,” he added.

Under questioning about why the Khmer Rouge gained popularity among people in Phnom Penh, Mr. Ponchaud testified that city dwellers could not grow rice and do business, and received assistance from NGOs and humanitarians organizations. All people prayed for peace, he said, emphasizing again that the populace had no hope under the Lon Nol regime, explaining how commanders would keep “ghost soldiers” on the payroll and pocket their salaries after they died.

In response to Judge Lavergne, Mr. Ponchaud said he did not know what people thought of the GRUNK (Royal Government of National Union of Kampuchea) or FUNK (National United Front of Kampuchea) but they knew Sihanouk would be “on their side” and the Khmer Rouge won the war with his support. He continued:

[People] believed that when the Khmer Rouge won the victory then King Sihanouk would eventually return to Cambodia, and the Khmer Rouge knew this even much better. For example in 1973, in February, they invited Sihanouk to the jungle in Kulen … and to Kulen Mountain [34]and Angkar tried their best to make sure that the soldiers could not see Samdech Sihanouk because they were afraid that Sihanouk could incite them to protest against Angkar. … They really looked down on both the King and Queen since 1970 when they were visiting Cambodia.

Mr. Ponchaud added that in 1973 people were afraid of the Khmer Rouge because they knew they had mistreated villagers in the countryside, and they knew of the so-called “seven traitors” but did not believe that information. Judge Lavergne asked if people were expecting the worse, to which the witness replied that he believed people were terrified of the looming misery, but they were powerless because there was no hope under the Lon Nol government.

Defense Queries Scope of Questioning for François Ponchaud

At this juncture, International Co-Lawyer for Nuon Chea Victor Koppe noted that Mr. Ponchaud was a witness and would be asked questions about what he had seen, but certain questions appeared to go to the opinion of the witness – such as what the Phnom Penh population was feeling – and sought clarification on how Mr. Ponchaud should be approached during cross-examination.

In response, International Senior Assistant Co-Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde stated that Mr. Ponchaud was present because he had witnessed events prior to 1975 and up to early May 1975, but the prosecution also wished to question him on his analysis of refugee accounts that he gathered in France and Thailand. Mr. de Wilde argued that Mr. Ponchaud was both a witness and an analyst, and also sought direction from the chamber. Mr. Koppe countered that “analyst” was not a legal term and Mr. Ponchaud was either a witness or an expert. If Mr. Ponchaud is to be considered an expert witness, Mr. Koppe contended, there must be a separate formal decision to that effect.

After judges consulted on the issue for several minutes, Trial Chamber Judge Silvia Cartwright informed the parties that Mr. Ponchaud had been called as a witness and the chamber would determine the relevance and probative value of questions put to him. However, she continued, he was not an expert in the technical sense and the chamber would deal with any concerns arising from the parties’ examination.

Judge Lavergne Questions Witness on Experiences in Phnom Penh

When Judge Lavergne resumed his questioning, Mr. Ponchaud confirmed that the church he had previously referred to was the Phnom Penh Cathedral, the municipality was the Bishop’s Palace, and Hotel Le Phnom is today the Le Royale hotel. When asked to describe the Khmer Rouge soldiers he met at the time, Mr. Ponchaud said there were two categories: young soldiers from 14 to 15 years old coming from the direction of Boeung Kak and stationed behind today’s municipal hall, and fierce-looking soldiers who were around 30 or older and were “bad people.” “If you look at their eyes they were very fierce indeed,” he recollected. “We did not want to get involved with them; we were simply terrified of them.” Mr. Ponchaud stated that people were moved out of the city by “psychological” force; they were happy and relieved when Khmer Rouge soldiers arrived in Phnom Penh because they assumed control without killing people.

The witness recounted that he had heard from others that the Khmer Rouge threw grenades inside hospitals when patients resisted their orders to leave. He said he heard from others that there were many wounded soldiers at Preah Ketomealea hospital, which the Khmer Rouge evacuated, but he did not witness this event.

Testimony Revisits French Embassy in 1975

Returning to the situation at the French embassy in 1975, Mr. Ponchaud confirmed to Judge Lavergne that marriages were arranged at the French embassy to facilitate the passage of some women, while some families also adopted orphans. He testified that people who took refuge inside the embassy were not important to the Khmer Rouge, which was focused on Cambodian people throughout the country. “Foreign nationals were not that important to the Khmer Rouge,” he said, adding that the Khmer Rouge assisted them and distributed rice and water when they ran out of food. “When the first batch of deportees left following April 30, the guard allowed us to kill the pigs around the French embassy to prepare food.” When asked if a representative of the Cambodian authorities was interacting with the French consul, Mr. Ponchaud recalled that someone was in charge of political negotiation – who told the embassy, for example, that Khieu Samphan wanted to meet them but was engaged elsewhere – but he could not recall his name, and Comrade Nhem assisted the embassy with securing food and water.

Judge Lavergne quoted from note cited in Francois Bizot’s book, signed by Nhem, vice president of the northern front of Phnom Penh in charge of foreigners, dated April 25, 1975, which states that the GRUNK decided as of that date that all foreigners still residing in the capital would leave as of April 30, through Poipet. Mr. Ponchaud said he did not see the note, but there was a discussion between the councillor, Bizot, and a Cambodian counterpart. Judge Lavergne then cited a GRUNK Ministry of Foreign Affairs communiqué dated April 29, 1975, which states that diplomatic missions accredited by the former regime cannot request regular diplomatic relations. He then inquired as to why, according to Mr. Ponchaud, there were no negotiations regarding Cambodians seeking refuge at the French embassy. Mr. Ponchaud replied that there was no negotiation and from what he heard, the Khmer Rouge, brandishing AK-47s, called for the embassy to surrender the “seven traitors.” He added that he heard there was correspondence with Paris that permitted expulsion of the “seven traitors” from the embassy.

Citing several telegrams between the French embassy in Phnom Penh and Paris in which people taking refuge inside the embassy were listed, Judge Lavergne noted that the French foreign ministry was requested to deliver those names to the municipality – which was demanding them – within the next 24 hours. He asked if GRUNK had announced that foreigners must leave Phnom Penh, to which the witness replied that by February 1975, Sihanouk had asked all foreigners to leave Cambodia. “[The] French government would like French people in Cambodia to leave Cambodia on March 19,” he added. “However, the French policy was not convincing because people trusted Prince Sihanouk and they had to wait and see.” Mr. Ponchaud told the court that a Chinese plane landed at Pochentong Airport on April 18, and there were others but he did not pay attention. He said that planes transported medicine from Bangkok, but the Khmer Rouge did not welcome such assistance.

When asked if he understood why villages and towns were empty during his journey from Phnom Penh, Mr. Ponchaud told the court that he understood later after a cadre told him that Phnom Penh was not a good place, city people did not grow anything and therefore had to go to the countryside to grow crops so that they understood the value of rice. Later in France, the witness added, Ieng Sary explained the evacuation by saying that there was no food in the city, there was a lack of safety and security, and the Khmer Rouge were concerned about riots.

However, to me the real reason behind this is more an ideology, a kind of reason that Angkar would like everyone to return to their hometown to become real Khmer because Khmer in Phnom Penh would be fake Cambodians. They had to move to the countryside, the home villages, to become the original Khmers.

Mr. Ponchaud commented that the Khmer Rouge were perhaps influenced by Mao Tse Tung’s cultural revolution that started in China in 1966 and that Mao appreciated Pol Pot for being brave enough to expel people from cities to the countryside. “Mao Tse Tung said that what he could not do could be done by Pol Pot and he appreciated the Khmer people for being that brave,” Mr. Ponchaud said.

Judge Presses Witness on Citywide Evacuation

Judge Lavergne inquired about Cambodian authorities’ reactions to information circulating about the evacuation, to which Mr. Ponchaud responded that he started probing for information starting in September 1975. The witness told the court that in France, Ieng Sary talked about good things in Cambodia, invited some students to return there, and said those who said bad things about Angkar were lying. Ieng Sary stayed that everything in Mr. Ponchaud’s book – published in 1977 – was wrong, he added.

The judge brought the witness’s attention to a press communiqué dated May 10, 1975, from the GRUNK Propaganda and Information Ministry, explaining that it had no choice but to force foreigners to leave. Though Mr. Ponchaud was unaware of the communiqué, he agreed that Angkar had paid attention to foreigners during a difficult period, but they were responsible for themselves and he would prefer to talk about Cambodian people at the time. When asked about his sources of information, the witness stated that he interviewed refugees, which one had to be cautious with because they sometimes exaggerated. He shared refugee accounts with other refugees in order to compare different stories and also listened to Democratic Kampuchea (DK) radio broadcasts:

I supported Angkar, and I believed that leaders of Angkar got educated in France – they were intellectuals. They were well-educated, so they would know much about what happened in Cambodia and to learn more about them I started to listen more to … the radio broadcasts by the DK and I got friends of mine who recorded the radio broadcasts and had them sent to me to listen. I would like to know the ideology of the Khmer Rouge and, as I told you, I had the idea or I understood that Khmer Rouge would not comprise of bad people. I was convinced that these people had a better plan for the good of their country, they would never do damage to their own people, for sure. … I listened to the radio broadcasts and at the same time I tried to explain to the refugees what happened in the country.

Judge Lavergne noted that in a written message to Judge Lemonde in December 2009, Mr. Ponchaud stated that he gave the judge summaries and French translations of 94 refugee accounts – about 300 typed pages – and translations and summaries of the accounts of about 100 refugees interviewed in Paris and Thailand. According to the message, Mr. Ponchaud gathered 94 accounts orally in Paris and Thailand between 1975 and 1976 and another priest took others down in refugee camps, which were translated and checked by Mr. Ponchaud in July 1976, mostly in Khmer with some in French. “The only aim of these accounts was to understand as best as possible the situation in DK in order for the French people to know about it,” Mr. Ponchaud stated, adding that he had used the documents to write his book and was unable to provide Khmer originals. Judge Lavergne inquired about the audio recordings of interviews with Khmer refugees, to which the witness replied that usually the interviews were recorded for verification but he had discarded these recordings.

Mr. Ponchaud told the court that he did not use the BBC as a source because he could not speak English but collected information about Cambodia from French bookstores that published and displayed communist books. He said such sources were sparse as Angkar did not write much.[35]Mr. Ponchaud confirmed that he had examined documents from the GRUNK mission in Paris. Judge Lavergne quoted from one such document, a transcript of an interview with Khieu Samphan dated August 12, 1975, which stated in part:

Our compatriots by the millions were locked up in concentration camps in Phnom Penh and in the other cities under enemy temporary control. The victims had no food. Cholera was decimating them. Families were torn apart and scattered throughout the entire country. Immediately after the liberation, the GRUNK and the FUNK, the people, and the People’s Army decided to tackle these problems with determination.

The witness told the judge that he did not recall the interview, but it was propaganda that was completely different to the situation described by refugees. Mr. Ponchaud said people did not understand why Angkar made them work hard to build dykes and dig reservoirs. He stated:

The Angkar wanted people to build dykes and dams in order to be self-reliant and self-sufficient for the country. This is the principal agenda of Angkar, and I actually myself find it satisfactory. … I actually did not like the way they treated people, they abused people or they actually made people work too hard, but actually I think that the plan was very well implemented and structured.

Mr. Ponchaud explained that the Voice of DK broadcast the last part of Khieu Samphan’s dissertation – though they did not say that it was an excerpt from the dissertation – to motivate people to work. “It was a fairly good plan,” Mr. Ponchaud said.[36]

Francois Ponchaud Criticizes UN Action during and after Khmer Rouge Period

After reading a lengthy list of sources used in Mr. Ponchaud’s various publications, Judge Lavergne zeroed in on his contribution to a report written by the International Commission of Jurists to the UN Human Rights Commission, published on August 16, 1978, in which he became one of the first to draw the international audience’s attention to events in Cambodia. Mr. Ponchaud testified that he did not understand the commissioner in Geneva who asked him to report to the UN committee on the human rights situation in Cambodia and proceeded to criticize the UN:

Back then I was like an object from nowhere, from another alien planet. Nobody listened to me. They did not pay attention to what I said at all. I wondered why they did not listen to me – that’s why, to be frank, I do not really like the way the UN worked. … They had their agents along the border; they must have known it very well. They knew that the Khmer Rouge had killed a lot of civilian people, but they chose to be indifferent of the situation.

Mr. Ponchaud testified that because of the Cold War and U.S. defeat in Vietnam, “residual issues” were left to China, which gathered support in the UN against the Soviet Union and, from 1979 onwards, China and the UN used the Khmer Rouge against the Soviet Union. He continued:

I am ashamed of the United Nations – they supported the Khmer Rouge for 19 years, even though they knew that the work that the Khmer Rouge had done was barbaric, and they killed innocent people, but they chose to be indifferent. What is the meaning of human rights? … We accept the value of human rights, but if we ignore the human rights abuses in the country I feel ashamed of the United Nations. I am actually ashamed that the United Nations is coming in and is now taking part in prosecuting the Khmer Rouge leaders. I am really ashamed of the United Nations; I don’t think that they should be involved in bringing the Khmer Rouge to trial now.

Midway through Judge Lavergne’s lengthy reading of findings in a report on Cambodia to the UN Human Rights Commission in 1978 – he asked Mr. Ponchaud to assess whether he still thought the findings relevant today[37] – International Co-Lawyer for Khieu Samphan Arthur Vercken argued that the bench was going beyond the confines of the trial. Mr. Koppe also voiced uncertainty as to whether Mr. Ponchaud should be treated like an expert. In response, Mr. de Wilde said the defense was raising two matters: the first was the relevance of the document, which he felt was clear as a number of passages read out dealt with executions occurring just after April 17, 1975, involving military officers. Secondly, Mr. de Wilde stated, in 1978 the witness was considered to have particular expertise and was speaking as an expert at the time.

Midway through Judge Lavergne’s lengthy reading of findings in a report on Cambodia to the UN Human Rights Commission in 1978 – he asked Mr. Ponchaud to assess whether he still thought the findings relevant today[37] – International Co-Lawyer for Khieu Samphan Arthur Vercken argued that the bench was going beyond the confines of the trial. Mr. Koppe also voiced uncertainty as to whether Mr. Ponchaud should be treated like an expert. In response, Mr. de Wilde said the defense was raising two matters: the first was the relevance of the document, which he felt was clear as a number of passages read out dealt with executions occurring just after April 17, 1975, involving military officers. Secondly, Mr. de Wilde stated, in 1978 the witness was considered to have particular expertise and was speaking as an expert at the time.

After a consultation among judges, President Nonn said the objection from the Khieu Samphan defense was overruled, as the questions were put by the bench, which would analyze the probative value of testimony. With this decision, Judge Lavergne stated that information in the report was directly linked to the present trial, as there were findings regarding the evacuations:

The population of Phnom Penh and of all of the cities and towns in the government zones were evacuated in days that followed April 17, 1975. Hospitals were emptied, the injured and the ill had to leave their beds and those who were not able to move were executed, and this involved more than 4 million people and caused the death of many elderly people, young children, and pregnant women.

Under questioning about what information the findings were based on,[38] Mr. Ponchaud testified that he interviewed hundreds of refugees, but emphasized that during the Khmer Rouge regime one place was different from another and he gathered information only from Battambang but not from other locations. “I thought that people would receive the same treatment all across the country, but I learned that indeed people were treated differently from one place to another,” Mr. Ponchaud said. He stated that when he wrote the report, he was unaware of the war between Khmer and Vietnamese officials but the Khmer Rouge had attacked the Vietnamese at the border and the hostilities resulted in casualties. Mr. Ponchaud further noted what Ta Mok – in charge of the Southwest – called the “second revolution,” whereby cadres were reshuffled all over Cambodia. “By 1977 and 1978, people in the rank of the Khmer Rouge, a lot of them died,” he added.[39] With this response, proceedings were concluded and are set to resume on Wednesday, April 10, 2013, at 9 a.m. with further testimony of witness François Ponchaud.