“Ghost Country”: Francois Ponchaud’s Testimony Continues

François Ponchaud, a French priest and long-time resident of Cambodia who wrote the 1977 bookCambodia: Year Zero, continued his testimony in Case 002 at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Wednesday, April 10, 2013. Prosecutors, civil party lawyers, and defense attorneys questioned Mr. Ponchaud, who was in Phnom Penh when the city fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975, after a prolonged civil war with the republican regime.

François Ponchaud, a French priest and long-time resident of Cambodia who wrote the 1977 bookCambodia: Year Zero, continued his testimony in Case 002 at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Wednesday, April 10, 2013. Prosecutors, civil party lawyers, and defense attorneys questioned Mr. Ponchaud, who was in Phnom Penh when the city fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975, after a prolonged civil war with the republican regime.

Today, 270 teachers and students from Kampot province watched the proceedings from inside the courtroom. Khieu Samphan was the only Case 002 defendant present in court, with co-accused Nuon Chea monitoring proceedings audio-visually from a remote holding cell, due to his health problems.

Prosecution Begins Examination of François Ponchaud

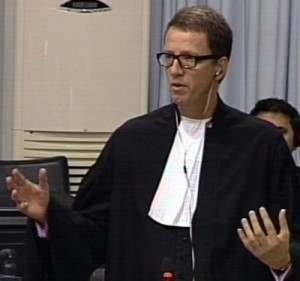

International Senior Assistant Co-Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde requested that Mr. Ponchaud explain his sources for previous comments that during the civil war, the Khmer Rouge evacuated citizens from conquered areas, killed local officials, burned houses, and took people into the jungle. Mr. Ponchaud clarified that American bombing between February 6 and August 15, 1973, killed about 40,000 civilians[2] and he gathered information from villagers. In Kampong Cham province in April 1975, he heard about Khmer Rouge soldiers burning villagers’ houses in Bos Knau – about 30 kilometers from Kampong Cham – evacuating people and killing commune chiefs, and received the same information about Damnak Chang Eou[3] near Kep, where there were Christian missionaries worked. Mr. Ponchaud said he met Christians in Kampong Kul – about 10 kilometers from Kampong Thom – where villagers were expelled from their homes and related the Khmer Rouge’s treatment of them in 1973.

People who came from the countryside to Phnom Penh during the civil war also talked about the situation in the countryside, the witness confirmed, including those who fled from the fighting and those fled from the Khmer Rouge specifically. “As the Khmer saying goes, when the elephants were fighting, the ants would be the victims,” Mr. Ponchaud said, adding that many fled from 1973 onwards due to U.S. bombing.

Mr. de Wilde quoted an excerpt from Mr. Ponchaud’s book Cambodia: Year Zero describing a woman who climbed a tree when she heard the Khmer Rouge approaching, preferring to have her legs eaten by red ants as some “children were being torn apart and some were being impaled.” The prosecutor queried why Mr. Ponchaud had written that he was not entirely convinced by certain accounts from people in the liberated zones. The witness responded that he did not understand the question but stated that he wished at the time for the Khmer Rouge to take over Cambodia even though they had mistreated people. He testified that people believed that when the Khmer Rouge won victory, they would live easily with the people, and described how Lon Nol soldiers had beheaded some villagers. “We saw the soldiers who were carrying decapitated heads of the villagers who were killed,” Mr. Ponchaud said, adding that people lost hope that Lon Nol soldiers would bring peace. “That’s why we trusted that only the Khmer Rouge would be the ones who could save us.”

However, Mr. Ponchaud explained that he changed his mind about the Khmer Rouge when their soldiers evacuated Phnom Penh, which he had thought was a wartime tactic in the villages.

Motivation behind Urban Evacuations Explored

Mr. de Wilde quoted a passage from Mr. Ponchaud’s book as follows:

The evacuation of Phnom Penh follows traditional Khmer revolutionary practice. Ever since 1972, the guerrilla fighters had been sending all the inhabitants of the villages and towns they occupied into the forest, often burning their homes so that they would have nothing to come back for. A massive total operation such as this reflects a new concept of society. The mere idea of cities had to disappear … all this had to be swept away and an egalitarian rural society put into place.

The prosecutor then quoted Mr. Ponchaud as saying to court investigators that the evacuation was part of the Khmer Rouge’s “systematic policy,” as they had expelled people from other conquered areas – such as in Kampong Cham in 1973 – but they did not believe this would occur in Phnom Penh due to its many inhabitants in 1975. When Mr. de Wilde inquired if Mr. Ponchaud had heard about the evacuation of Udong, the witness confirmed that he had. Cities were established by the French colonial regime, Mr. Ponchaud emphasized, and he recalled hearing from a Khmer Rouge cadre at Hotel Le Phnom on April 18 – though he did not know if it reflected statements made by Khmer Rouge leaders – that corruption was widespread in the city and if people returned to the countryside to farm they would appreciate the real value of life. Mr. Ponchaud recalled that Cambodian people used to tell him Vietnam was Cambodia’s enemy but the soldier told him that Chinese people were the enemies because they were in charge of money, and Khieu Samphan had spoken of these “compradors” on Khmer Rouge radio. “The Chinese took the advantage of bringing the produce of the farmers to sell to the foreigners for benefits,” he said, adding that city dwellers were considered corrupt with improper conduct and appearance.

Quoting further sections from Mr. Ponchaud’s book, Mr. de Wilde queried whether the witness observed differences between the solemnity of the Khmer Rouge – “they were the only ones who were not rejoicing” – and the people’s jubilation. Mr. Ponchaud described how people congratulated people they mistakenly believed were Khmer Rouge soldiers travelling in trucks into the city, who were in fact Lon Nol soldiers who had surrendered. He detailed how young Khmer Rouge soldiers donning Maoist caps had unpleasant facial expressions and appeared exhausted. The soldiers did not advise people to bring belongings as they ordered them from the city, Mr. Ponchaud said, and did not tell anyone they would receive assistance on the journey.

Under questioning from Mr. de Wilde about a comment by Khmer Rouge soldier Comrade Nhem that Mr. Ponchaud would be welcomed back to Cambodia once they “cleaned” it up, the witness explained that at the time he believed the Khmer Rouge wanted to purge the city of officials from the Khmer Republic. After Mr. de Wilde pressed him on whether refugees and former military officials described executions to him, Mr. Ponchaud related a story about a man about 50 years of age – originally from Kien Svay[4] – whom he met at the French embassy around April 22, 1975.[5] The man told Mr. Ponchaud that Angkar requested military officers and high-ranking officials from the previous regime to write their names on a board in Kien Svay pagoda, and they were later killed. The witness stated that he also obtained information later – detailed in his book – indicating that the Khmer Rouge had executed soldiers and commanders at Phnom Thipdey.[6]

Mr. Ponchaud testified that people who left Phnom Penh at the time of the evacuation were frightened and sad and unaware of where they would end up or where they were supposed to go.[7] The witness said he did not see Khmer Rouge soldiers guarding people leaving the city or people being shot, but he occasionally saw the Khmer Rouge escorting people. He told Mr. de Wilde that he heard rumors about patients who refused to leave hospitals being executed but did not witness it himself. When asked about a disabled person he declined to receive in his residence at the time, Mr. Ponchaud stated that usually when the Khmer Rouge found Cambodians living with French people, both were killed.

The witness further stated that “sooner or later” wounded and sick people being evacuated would have died. After the prosecutor queried whether a reasonable observer watching the evacuation unfold would conclude that sick and injured evacuees would eventually die, International Co-Lawyer for Nuon Chea Victor Koppe objected that the witness could not know the thoughts of a “reasonable observer” and his answer would be legally irrelevant. Mr. de Wilde noted that the Chamber had told parties it would determine such disputes on a case-by-case basis, and he was merely inquiring if the witness’ opinion would have been shared by others who observed the scene. The objection was sustained, and the prosecution moved on.

Mr. de Wilde queried whether, as an intellectual, Mr. Ponchaud ever wondered why the Khmer Rouge were evacuating the city supposedly to protect people from bombing but in doing so, were forcing the wounded and sick to leave hospitals. The witness responded that aside from supposed imminent bombing, the Khmer Rouge felt city dwellers would understand the value of life if they went to the countryside to undertake agricultural labor and grasp that rice was the “source of their life.” Elaborating on his time in Phnom Penh after April 17, Mr. Ponchaud repeated that soldiers did not exert physical pressure on him, but psychological pressure, which was similar to that inflicted on him when he was captured by the Viet Cong on May, 4, 1970 – an event he did not disclose to anyone for three years due to his fear.

I did not believe that there would be bombing by the Americans, but as poor Cambodian ordinary citizens, they would believe in it because a few years back there were American bombings everywhere some 40 kilometers away from the city, so they still had that memory with them and they were frightened. So even the Khmer Rouge … did not believe and I did not believe it either, but … the ordinary citizens, they might have believed it.

Ieng Sary Interview Probed

The prosecutor cited an interview with Ieng Sary by James Pringle in which he did not mention imminent U.S. bombing as a justification for the evacuation of Phnom Penh, and asked the witness if the Khmer Rouge had expelled residents from Phnom Penh on a false pretext. Mr. Ponchaud replied that it was clear the Khmer Rouge had lied, and he believed the real reason for the evacuation was ideological. Mr. de Wilde noted that Mr. Ponchaud wrote in his book that rice reserves in the capital were sufficient to feed the population for over two months and that several thousand tons of rice rotted in Kampong Som without being used,[8] asking him about his sources for this information. The witness responded that he saw the information about rice in Sihanoukville in the newspaper, and he estimated the amount of rice in Phnom Penh.

After Mr. de Wilde asked Mr. Ponchaud whether it would have been easier for the Khmer Rouge to seek international support after the liberation and avoid evacuation, Mr. Koppe stated that the prosecutor was asking the witness to speculate. Mr. de Wilde moved on with his questioning, quoting Ieng Sary as saying in the aforementioned interview with James Pringle in September 4, 1975, that Phnom Penh was that about 100,000 people had returned to Phnom Penh, that schools, factories and hospitals were active again and people could return to the city if they wished. “Cambodia looks like a giant workshop,” Mr. de Wilde quoted Ieng Sary as stating in the interview. When asked if this comment corresponded with refugee accounts collected by Mr. Ponchaud, the witness replied that Ieng Sary was lying and that segments of the population had been evacuated again in July and September 1975. “I met refugees who traveled across Phnom Penh and they told me that Phnom Penh was empty,” the witness recalled. “They cried because they saw their house and they said that Phnom Penh was empty. No one was in Phnom Penh.”

Mr. de Wilde inquired about trucks mentioned in Mr. Ponchaud’s book that carried men and women into Phnom Penh. The witness said he could not remember, but he related meeting about 10 Catholic wives of high-ranking soldiers who told him they had been asked by Angkar to go to Hotel le Phnom. They said they were not frightened, that Angkar was “fine” and had asked their husbands to go to the city to rebuild the country, Mr. Ponchaud said. “Angkar was very good at telling lies,” he added. “They told those people to go back into Phnom Penh and then they killed those people.” In answer to Mr. de Wilde’s question on what refugees recalled about the fate of former regime officers in Battambang province, Mr. Ponchaud testified that in 1975, the Khmer Rouge aimed to destroy all people who worked for the U.S. and the Lon Nol regime, whom they regarded as traitors, then in 1976 they forced all to join the lower class and in 1977 – “the socialist revolution” – they created cooperatives. He stated that at Phnom Thipdey in Battambang, the Khmer Rouge killed 380 people, based on the accounts of four witnesses:

[Pain Roeun] told me that the Khmer Rouge told us to welcome Samdech Ouv[9] who came back to Cambodia.Therefore those soldiers said goodbye to their wives and wore their uniforms and then boarded a truck. Then they traveled for around 15 kilometers and then they turned to O’Preah. When the truck arrived at Thipdey mountain the Khmer Rouge soldiers were waiting over there and those former high ranking soldiers were gunned down. Pain Roeun was injured and fled the scene. Around six months later, I met another refugee named Ieng Sovannary.I changed their names, and their relatives asked about their information. Ieng Sovannary walked across Thipdey Mountain and he saw a lot of dead bodies, skeletons, skulls.

After Mr. de Wilde asked what happened to non-commissioned officers in Thmar Kol,[10]International Co-Lawyer for Khieu Samphan Arthur Vercken argued that questions should be clearer in emphasizing that Mr. Ponchaud was relating information told to him by others, rather than events he had seen himself. Mr. Koppe chimed in add that in some evidence provided was “double hearsay,” meaning information that someone the witness had spoken to had heard from a third person. The prosecution argued that the aforementioned evidence related by Mr. Ponchaud had come from four witnesses he spoke to directly. In response to Mr. de Wilde’s original question, Mr. Ponchaud stated that initially Khmer Rouge killed high-ranking soldiers and released lower ranking soldiers, but later killed all soldiers.

Deciphering Khmer Rouge Policies and Slogans

Citing passages from Mr. Ponchaud’s book, Mr. de Wilde inquired if, based on his interviews with refugees, it appeared that all people returned to Phnom Penh after April 17, 1975, were broken into three groups – military personnel, civil servants and civilians. “I believed that Angkar did the same everywhere,” the witness said. He noted well-known Khmer Rouge slogans like “keeping you is no gain, losing you is no loss” and “killing a person by mistake is better than having him released by mistake.” After reciting a series of additional slogans listed in Mr. Ponchaud’s book,[11] Mr. de Wilde attempted to explore the Khmer Rouge’s interpretation of purity. The witness responded:

The pure Khmer people are those who do not take private ownership as important, and Angkar took that as honor or prestige that they offered or they dubbed the pure people a docile instrument in the hands of Angkar. So the pure people did not possess their own thoughts. They had to devote to follow the Angkar policy and plan. They care only for the interests of the nation.

The prosecutor quoted at length from an April 21, 1975, speech by Khieu Samphan broadcast on Radio Phnom Penh outlining the Democratic Kampuchea’s (DK) revolutionary objectives and describing its “great victory” over the enemy. Mr. Ponchaud said he only recalled a FUNK (National United Front of Kampuchea) radio broadcast in which the Khmer Rouge said they won victory through “conventional weapons.” Mr. Ponchaud testified that at the time they did not pay much attention to Khmer Rouge propaganda but noted that they used different language, discussing independence, no private ownership, and the “organizational stance.” The witness stated that Angkar used the terms “April 17 people” or “new people” to refer to those who were liberated by the Khmer Rouge, and “old people” or “base people” were those who had lived in the countryside all along. He added that they sometimes talked about “prisoners of war” but not “slaves.” “The new people or the April 17 people did not enjoy any freedom at all,” Mr. Ponchaud told the court. “Later on, from 1977, both the base or the old people and the new people did not enjoy any freedom. From 1977, the new situation occurred when there was conflict between Cambodia and Vietnam.”

Again reading an excerpt from James Pringle’s September 1975 interview with Ieng Sary, Mr. de Wilde inquired if Mr. Ponchaud heard refugees discuss “open air prisons.” The witness said refugees mentioned “prisons without walls” but Khmer Rouge radio referred to them as worksites, where people worked day and night.

Prosecution Returns to the French Embassy in Phnom Penh

At this point, National Senior Assistant Co-Prosecutor Dararasmey Chan took over the witness examination, asking Mr. Ponchaud if people who had to leave the French embassy in Phnom Penh were forced at gunpoint. Mr. Ponchaud replied that he did not know of anyone being forced to leave at gunpoint or threatened, though nobody resisted Khmer Rouge orders. The witness said he knew Comrade Nhem – an intermediary between the embassy and Angkar – but did not meet anyone else from Angkar. Mr. Ponchaud testified that on the road from Phnom Penh to the border they “did not see a soul” though they saw some smoke coming from fields and villages.

Under questioning from Mr. Chan about any resistance to evacuation, Mr. Ponchaud repeated that only some Lon Nol soldiers were still fighting the Khmer Rouge and he occasionally heard what he thought were gunshots. Mr. Ponchaud stated that Angkar usually allowed family members to stay together at the time, but some were separated on ferries after walking to Prek Kdam.[12] “When the ferry was full, for example if the family members would already be on board the ferry and the remaining family members would be on the other side of the river, then the KR would never care to bring them together,” he said. Finally, Mr. Chan queried whether different groups of people such as Cham Muslims, Vietnamese or Chinese people were treated differently, to which Mr. Ponchaud replied that in late 1975, Angkar allowed some Vietnamese people to return to their country. With this response, the prosecution concluded their questioning of François Ponchaud.

Civil Party Lawyers Question François Ponchaud

National Civil Party Co-Lawyer Moch Sovannary started the civil party lawyers’ examination of Mr. Ponchaud by probing his discussion with the group of soldiers who came to his home on the evening of April 17, 1975. The witness replied that the soldiers came from Siem Reap and were not particularly friendly, thus he was not brave enough to ask them about ideology or Angkar’s plan. He confirmed that he had transported a group of soldiers to the railway station.[13] When asked why he had previously assumed that Comrade Nhem was not a senior official, Mr. Ponchaud said that he and François Bizot[14] had communicated with Nhem everyday, but did not discuss policy. Later, he added, a cadre who called himself a “higher ranking official” came to the embassy to inform them that Khieu Samphan wished to meet those in the compound and another cadre discussed the repatriation of foreigners at the embassy so he assumed they were higher ranking.

Khieu Samphan’s Position and Role Explored

Mr. Ponchaud told the court the latter informed them that Khieu Samphan was among the leaders of the country but did not mention his specific position or any other official. He explained that in his book he mentioned the names Pot, Hem, and Van[15]who were high-ranking officials in the upper authority. Mr. Ponchaud testified that he did not know who Comrade Pot or Comrade Hem were at the time, but Comrade Hem was with them in court now, which seemed to elicit a smile from Khieu Samphan. Mr. Ponchaud mentioned Comrade Vorn, or Vorn Vet, and said that then he did not know who headed Angkar, but he learned in September 1977 that Saloth Sar was Pol Pot, who announced the Community Party of Kampuchea’s (CPK) existence in China.

Mr. Ponchaud told the court the latter informed them that Khieu Samphan was among the leaders of the country but did not mention his specific position or any other official. He explained that in his book he mentioned the names Pot, Hem, and Van[15]who were high-ranking officials in the upper authority. Mr. Ponchaud testified that he did not know who Comrade Pot or Comrade Hem were at the time, but Comrade Hem was with them in court now, which seemed to elicit a smile from Khieu Samphan. Mr. Ponchaud mentioned Comrade Vorn, or Vorn Vet, and said that then he did not know who headed Angkar, but he learned in September 1977 that Saloth Sar was Pol Pot, who announced the Community Party of Kampuchea’s (CPK) existence in China.

Khmer Rouge Propaganda Described by Witness

The witness recalled that Ieng Sary traveled to France and appealed to Cambodian intellectuals to return to Cambodia to help rebuild the country. Mr. Ponchaud added that Ong Thong Hoeung returned to Cambodia after hearing Ieng Sary’s address, though he warned Ong Thong Hoeung not to go back.[16] “[Ong Thong Hoeung] accused me of being CIA,” he said, adding that Angkar used to lie in order to lure people into following them and executed innocent people.

Ms. Sovannary quoted from a document written by Mr. Ponchaud, which stated that Cambodia was turned into “an open worksite” and “people did not consider whether they were working during the day or night – they were working tirelessly with joy.”[17] When asked what he based this comment on, Mr. Ponchaud explained that this excerpt was a direct quote from a DK radio broadcast, and, additionally, when he started researching Cambodia in September 1975, he relied on the accounts of refugees who did not, in fact, work with joy or pride.

They said they worked day and night, but earlier on I could hardly believe them because it was beyond anyone’s imagination. … At that time I thought that Angkar was not crazy enough to make people do such a harsh job, because the Angkar’s leaders were well educated, like Saloth Sar was educated in France. So I thought that they must have had a very well organized plan to develop the country. I thought in the first place that they had good intentions for the development of the country, so I at that time paid more attention to listening to the Khmer Rouge radio broadcast in order to follow the political lines.

In answer to a question from Ms. Sovannary about whether Cambodian refugees he interviewed in his book told him why they left Cambodia, Mr. Ponchaud told the court that various people, including civil servants and former regime soldiers, went to the border to escape – some because they were corrupt. “Some people who live some 30 kilometers away from the border, they heard from others that the Khmer Rouge killed so many people so they decided to flee the country,” he added. The civil party lawyers pressed Mr. Ponchaud for detail about the experiences of refugees from the second population movement, and Mr. Ponchaud recalled that some people were transported from Takeo province to Phnom Penh and then taken by train to Phnom Thipdey near Mongkul Borei.[18] Mr. Ponchaud said there were many casualties:

It was barbaric treatment. They were staying in the wagons of the train. They were not given food. They were not given water. They did not have place to [defecate] or to relieve themselves. They had to stay in the small wagon packed with people.

Lawyer Examines François Ponchaud’s Published Work

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Elisabeth Simmoneau Fort assumed the witness examination, citing Mr. Ponchaud’s report to a United Nations human rights committee in 1978 in which he mentioned human rights violations, and his published articles in French daily Le Monde.Ms. Simmoneau Fort inquired if Mr. Ponchaud’s observations in the report to the UN about the population movement were based on what he heard and learned in Cambodia up until his departure in early May 1975. The witness replied that up until May 1975, he only saw the evacuation of people from Phnom Penh and his other knowledge was gained from interviews with refugees starting in September 1975. “I saw the evacuation of 200 or 300 people along Monivong Boulevard,” Mr. Ponchaud recollected. “People of all ages – children, women, patients – were all evacuated. … They would surely die, those women who have just given birth would have little chance to survive.”

Ms. Simmoneau Fort asked about findings in the same report about the lives of people and families in cooperatives and work camps, describing husbands and wives being separated and reunited only occasionally – especially for new people – and children left to older women in cooperatives and practically separated from their parents who from the age of 6. From the age of 13 or 14, children joined mobile units, Ms. Simmoneau Fort read from the document, and rarely saw their parents. She also quoted from one of Mr. Ponchaud’s articles in Le Monde dated April 17, 1976, in which he stated that Angkar seemed bent on “exploiting human potential to the very limit of its physical strength.” Under questioning from Ms. Simmoneau Fort about the source of this information, Mr. Ponchaud testified that he had interviewed refugees in Thailand and France and Khmer Rouge radio had provided information about mobile children’s units.

I learned about the Khmer Rouge society through the Khmer Rouge radio. I learned about the children’s unit, which was in charge of collecting cattle excrement and plants to be used as fertilizer. Later there were mobile units, women’s units – so this is the explanation from the Khmer Rouge radio – and they divided the people into two groups: those who were married, husbands were assigned to work far away to clear forests, to plow rice fields, to fish. Women worked closed to the villages. The Khmer Rouge radio explained that old age people aged from 55 upwards were assigned to make tools for farming, and they said that those people described their work in happiness, they enjoyed working. … Khmer Rouge radio broadcast, broadcast about how the society should be educated and also how people lived their lives.

The civil party lawyer cited observations from the 1978 report to the UN on the re-education or elimination of people who did not follow Angkar’s instructions, including executions, and quoted from Mr. Ponchaud’s February 18, 1976, article in Le Monde as follows:

The person who does not follow Angkar’s instructions is sentenced to ‘construction’ a term, which is synonymous with a reprimand coupled with punishment, food deprivation, standing in the hot sun, etc. If such persons do not mend their ways, they are sent to disciplinary facilities for collective training and if they disobey orders from Angkar for the third time, they are summoned the “supreme organization” – Angkar Leu[19]– from where no one returns.

Mr. Ponchaud confirmed that information in the article came from interviews with witnesses and stated that his report was based on refugee accounts that were consistent with reports from DK radio. Again, Ms. Simmoneau Fort referring to a section of the 1978 report that described wealthy people and monks executed a few days after the liberation and other monks being forced to lead a lay lifestyle as of 1976. According to the report, she read, pagodas were converted into warehouses and Buddhist statues destroyed, Muslims were persecuted and Christians and animists could not express themselves. Ms. Simmoneau Fort then quoted Mr. Ponchaud as saying in two 1976 articles in Le Monde that accounts confirmed purges of military and administrative officials and the persecution of Cham Muslims, through the destruction of religious books, the obligation to eat pork, and being forced to give up certain vestments. In response to a query about the number of accounts these documents were based on, the witness testified that he got many stories from monks – who were forced to leave the monkhood bar a handful used by Khmer Rouge leaders – and other sources provided information about the Cham. Mr. Ponchaud elaborated:

I do not believe that the Khmer Rouge mistreated the Cham based on religious principles. The ethnic Cham had their own traditions and the Khmer Rouge wanted all the people to do the same thing, so those who agreed to follow the Khmer Rouge would survive, now matter they are the ethnic Cham, or the Vietnamese, but if they did not follow the Khmer Rouge they would be in danger. Since 1978, the situation became strange. They searched for the Muslims, the Khmer Islam, because of the conflict between Cambodia and Vietnam, and ethnic Cham were suspected to support the Vietnamese.

Under questioning from Ms. Simmoneau Fort about another section of his report related to forced marriages, Mr. Ponchaud stated that he received many accounts of marriages arranged by Angkar:

Women who rejected the marriage with Khmer Rouge soldiers who were handicapped committed suicide. … I know two couples who lived with each other until now. Their marriage was arranged by Angkar. I would like to say that Angkar was the parents of the people. According to the Cambodian tradition, parents arranged the marriage for their children, so Angkar had the right to arrange the marriages for the children. I do not like that practice, but of course this is the view of Angkar.

Ms. Simmoneau Fort read a final excerpt from Mr. Ponchaud’s article published in Le Monde on February 18, 1976, which stated that refugees categorized people as old people and new people, who were considered prisoners of war who had no rights. “The absence of medicine, work without stop, makes us envisage an incredible loss of human life,” the civil party lawyer read from the article, asking Mr. Ponchaud if such observations were based on refugee accounts. The witness responded that refugees told him many people died from every family and recounted studies listing various figures for the number of people who died under the Khmer Rouge.

Finally, Ms. Simmoneau Fort read testimony from a civil party about the second population transfer in December 2012.[20] This party described boarding a truck to Pursat province in which passengers were not allowed to step off the vehicle to relieve themselves and were later grouped into a freight car. When asked if the testimony resembled accounts from refugees in the late 1970s, Mr. Ponchaud agreed. With this reply, the civil party lawyers finalized their examination of the witness.

Khieu Samphan Defense Leads Cross-Examination

Beginning the defense teams’ questioning of the witness, National Co-Lawyer for Khieu Samphan Kong Sam Onn inquired how Mr. Ponchaud came to know of his client. The witness explained that he heard of Khieu Samphan initially in 1966 when Cambodia was under Sihanouk’s government – the Sangkum Reastr Niyum – and knew him to be a “clean person” who believed in justice and was mistreated by police in front of the National Assembly, though he did not know why. “I still admire him greatly,” he stated, adding that Sihanouk mistreated and tried to arrest Khieu Samphan and implied that he was dead, along with Hu Nim and Hou Yun. Mr. Ponchaud stated that he had heard of articles written by Khieu Samphan in L’Observateur,[21] which was eventually ordered closed by Sihanouk. “Even during current days,” Mr. Ponchaud said, “clean people who do some harms to some other people in a sense would then be not wanted.”

Under questioning from Mr. Sam Onn about Khieu Samphan during this period, Mr. Ponchaud testified that youth, intellectuals, and teachers called him “Mr. Clean” because they did not like Sihanouk and believed he led a corrupt government. Such groups wished to free their country from monarchic rule, and Saloth Sar and Ieng Sary – both teachers at Kampuchea Both school – they were liked and believed to be communists, the witness said. Mr. Ponchaud recollected that Khieu Samphan fled to Kampot province because villagers in Samlaut[22] revolted against the government for grabbing their land – stealing weapons from soldiers – and Sihanouk accused Khieu Samphan, Hu Nim, and Hou Yun of being traitors as he considered that his people would not rebel without someone being behind it. The witness described how film footage of a man named Preap In being tied to a pole and shot dead by soldiers screened before films in the cinema. “King Norodom Sihanouk was not familiar with how the power would be properly distributed,” he said. Mr. Ponchaud explained that after Khieu Samphan’s disappearance, he believed the three men to be dead but they were later discovered to be alive.[23] At this point, Mr. Sam Onn asked a series of questions about an “Italian journalist” named “Mr. Christiana,” whom Mr. Ponchaud called a liar because he made up stories about DK and fabricated an interview with Khieu Samphan.[24]

François Ponchaud Details Time under Sihanouk’s Government

Mr. Vercken took over questioning of the witness, pressing him for an explanation of the term “cosmic revolution” used in his earlier testimony when discussing Sihanouk’s reputation prior to the 1970 coup d’état. Mr. Ponchaud replied that to peasants, the King was “master of the land and water” and people could only grow and sow crops after the royal plowing ceremony[25] – “no king, no rain” – so when Sihanouk was toppled, peasants felt that they could not farm. The witness explained that students who had returned from France did not like Sihanouk and wished to seize some power, which Sihanouk was not prepared to relinquish. A Cambodian communist named Chao Seng who married a Frenchwoman was education minister, meaning that communist leaders headed educational departments, Mr. Ponchaud recalled.

He further testified that people were forced to watch the film Apsara,[26] which depicted Phnom Penh as a place for the rich – without cattle, oxcarts and peasants – where officials acted like gangsters. Sosthene Fernandez, who was in charge of suppressing gambling, led a casino, and Nhek Tioulong – the head of the army – was decadent in the film, Mr. Ponchaud recalled. “The people in the countryside were saying is that what Phnom Penh is about? Is that what Sihanouk’s government is about? They could only be flabbergasted, and I understood very clearly that the communists were furious against Sihanouk and wanted to destroy him,” he said.

When asked how the Lon Nol regime eventually dealt with the image of Sihanouk after deposing him, Mr. Ponchaud testified that the Lon Nol administration miscalculated in distorting and defaming Sihanouk, who was depicted as naughty and living a luxurious life, eating from a golden plate.[27]Sihanouk found this “unacceptable and unbearable,” Mr. Ponchaud said, adding that newspapers printed horrible cartoons of Sihanouk and Monique[28] making love. He continued:

This is of course not something that is acceptable for a head of state even if he’s been overthrown. Every head of state deserves respect even if he is our political enemy, so Sihanouk was not able to accept that, of course. And in fact he says it himself in hisChroniques de guerre et d’espoir, if they had simply deposed me, simply I would have maybe gone to … France, and I would have stayed there, that’s all. And then I would’ve just ended my life peacefully, but as a Khmer he could not accept or he could not react to this kind of insult. And when Khmer people lose face they are even capable of committing suicide to cleanse their honor. I’m convinced that Sihanouk supported the Khmer Rouge, of course because he was a bit of a nationalist, but also and above all in order to cleanse his honor, even if this meant the death of many Cambodians. Even our French compatriots … wrote horrible editorials about Sihanouk which a Khmer worthy of this name cannot accept under no circumstances.

After Mr. Vercken asked the witness if he believed Sihanouk knew what would happen when he supported the Khmer Rouge, Mr. Ponchaud emphasized that he himself did not really support the Khmer Rouge revolution, but noted that Cambodians had no hope under Lon Nol’s administration. The witness recalled his earlier hope that Sihanouk’s regime would improve. “Back then, there were many, many students, professionals, who were against Prince Sihanouk but not necessarily as revolutionaries,” he said.

Mr. Ponchaud testified that even within the Khmer Rouge, Khieu Samphan, Hou Yun, Hu Nim, and Chao Seng believed in a fairer communist regime, while another branch of the Khmer Rouge – including Saloth Sar or Pol Pot, Ieng Sary,Rocheon Ton, Roth Samoeun, andSon Sen – had decided since 1963 that the only way to end Sihanouk’s feudalist regime was to forcefully overthrow him.

Defense Inquires about Perceptions of Khieu Samphan

Referring to Mr. Ponchaud’s time at the French embassy after the fall of Phnom Penh, Mr. Vercken inquired if the mention of Khieu Samphan’s name by a Khmer Rouge cadre was “reassuring.” Mr. Ponchaud disagreed and said that Khieu Samphan was just one among a number of Khmer Rouge leaders.

The defense lawyer proceeded to quote from a letter from Thailand that appeared to have been sent to Mr. Ponchaud, dated November 21, 1975 and an excerpt from a January 1976 article by Mr. Ponchaud, both of which referred to a “silence” around Khieu Samphan, pushing for detail on both documents. Mr. Ponchaud responded that he recorded what he heard on DK radio and it should be remembered that Khieu Samphan was not Brother Number One or Two – Saloth Sar and Nuon Chea respectively – and was behind Ieng Sary in the hierarchy.

When Mr. Vercken pressed for information about a military official named Pich Lim Kuon[29]mentioned by Mr. Ponchaud earlier, who was “significant” to the defense because he stated in a media interview that there were two sets of government operating at the time.[30] Mr. Ponchaud concurred that he met Pich Lim Kuon – a helicopter pilot who advised Angkar – in Thailand, perhaps around July 1976. The witness said, “He was responsible for all of the travels of Angkar. I asked him what Angkar was – he said Angkar comprised of Comrade, Pot, Hem, Vorn, and I asked him again who was Comrade Pot and he said he didn’t know.”

Growing frustrated with the translation,[31] Mr. Ponchaud responded to a question from Mr. Vercken about Phnom Penh after the evacuation by stating that as a result of Khmer Rouge propaganda, soldiers believed there were American soldiers in Phnom Penh. He explained that there were in fact only a few US advisers and the head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in Cambodia, was at the French embassy – a fact known to everyone.

Khmer Rouge Language Discussed

The defense sought Mr. Ponchaud’s explanation of the “warlike language” used by the Khmer Rouge to describe even mundane daily tasks,[32] to which the witness replied that understanding the Khmer Rouge’s mistakes required comprehending that they were victorious over the Lon Nol administration because of the US bombings in Cambodia. “They said peace was a new war,” Mr. Ponchaud said, before elaborating:

There were two battlefields: the front battlefields … [which] referred to digging canals, digging dykes; and the rear was about normal work in the villages and everything was, people were organized like an army, to grow or to do farming. The regular army or the mobile units comprised of youth were meant to build canals and dykes. And there was another group comprised of people who got married and their husbands would be working far from home. So all the people could be regarded as a group of army that attacked, but attacked in the sense of cultivation, production.

Mr. Ponchaud explained that even today, people unknowingly used Khmer Rouge language.

Thailand’s Position on Border Refugee Camps Examined

After Mr. Vercken questioned Mr. Ponchaud about Thailand’s position on the refugee camps in its territory, a somewhat confusing exchange ensued between lawyer and witness. Mr. Ponchaud testified that Thailand claimed there were no Cambodian refugees in the country when he crossed the border in May 1975, but there were in fact thousands living along the border in about 20 refugee camps between 1975 and 1976.[33] “Thailand agreed to welcome the refugees who were against the Khmer Rouge, but Thailand controlled the refugees in order to achieve its own political gains,” the witness said, adding that from 1979 onwards hundreds of thousands of refugees fled into Thailand.[34]

At this point, Ms. Simmoneau Fort requested that questions more clearly indicate specific dates and references to avoid confusion, to which Mr. Vercken replied that questions that were too specific might lead to objections that he was leading the witness. The defense lawyer proceeded to ask if the refugees experienced any threat that they would be sent back to Cambodia by Thailand. Mr. Ponchaud said that between 1975 and 1978 during the DK regime, there were about 50,000 refugees in Thailand and the country did not like their presence but had no choice but to accept them. Thai authorities killed some refugees, he added, and Thai soldiers killed some Cambodian soldiers who created an army to oppose the Khmer Rouge.[35]

When Mr. Vercken queried whether these circumstances influenced refugees’ accounts of Cambodia, Mr. Ponchaud answered that he believed Cambodian refugees in Thailand had difficulties living there.[36] For a few moments, Mr. Ponchaud shouted in French, appearing frustrated by the translation of his testimony. He then explained in Khmer that he did not wish to testify in French in case it appeared to the prosecution that he was favoring the defense. However, he requested to switch to testifying in French if the prosecution had no objection to it. The Chamber permitted Mr. Ponchaud to testify in French. Mr. de Wilde requested confirmation that Mr. Ponchaud had said that the refugees were speaking the truth. Mr. Ponchaud explained that he said even considering the political context in Thailand and oppression of refugees by the Thai army, he believed the refugees spoke truthfully about their experiences in DK.

Though Mr. Vercken noted that people could be misleading, assured Mr. Ponchaud that he did not intend to question the honesty of his work but merely inquire about the difficulties he faced while interviewing refugees in a complex situation and in a country that did not accept them. Mr. Vercken then asked about an issue Mr. Ponchaud appeared to have raised to the investigating judges, of people identifying refugees ahead of his interviews with them.[37]

In response, Mr. Ponchaud testified that “ridiculous” things were said about him – for example, after his article was published in Le Monde, Libération[38]described him as a priest, journalist, “French secret service agent” and “CIA” agent, and wrote that refugees were chosen ahead of time by camp leaders. He stated that he did not need people to choose refugees for him, and he just attended the camp and speak to people directly. “It was not the camp administration that would determine ahead of time which refugees I would have to interview,” he said. “I would even say this was defamation. Nobody ever chose people for me to interview and this should be clear.”

Mr. Vercken noted that in Mr. Ponchaud’s book he described the “12 revolutionary commandments” known by refugees and recited every morning by soldiers guarding the French embassy after the fall of Phnom Penh. The defense lawyer inquired if being thoroughness regarding propaganda was important within the Khmer Rouge. The witness concurred, stating that Khmer Rouge soldiers were disciplined and at the French embassy, soldiers aged 13 or 14 would recite the commandments. Generally speaking, the Khmer Rouge behaved strictly and ethically in the sense that they would kill if they felt it necessary, and stuck to “a strict moral line” – though there were some incidences – particularly in terms of sexual conduct.

President Nonn announced that the hearing had concluded for the day, with proceedings set to resume on Thursday, April 11, 2013, at 9 a.m., with further questioning of François Ponchaud.