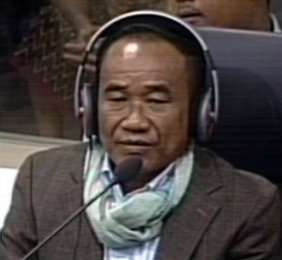

After Significant Initial Resistance, Former Khmer Rouge Commander and Convicted Murderer Chhouk Rin Testifies

Chhouk Rin, a former Khmer Rouge commander now serving a life sentence at Prey Sar Prison for the murder of three foreign tourists in 1994, began testifying in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Monday, April 22, 2013. Following a week-long break in hearings due to the Khmer New Year holidays, it initially appeared that the Trial Chamber might be unable to resume hearing testimony, with Mr. Rin posing significant resistance to answering any questions at the outset, citing poor health and requesting the Trial Chamber for a medical examination or for assistance with his circumstances at Prey Sar. However, under the pressure of dogged questioning, Mr. Rin finally relented. By the end of the day, he was offering the Chamber detailed testimony in response to questions from the prosecution on a wide range of issues, most notably the role of Nuon Chea, purges of internal enemies, the battle between the Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol forces, and the evacuation of Kampot town.

Chhouk Rin, a former Khmer Rouge commander now serving a life sentence at Prey Sar Prison for the murder of three foreign tourists in 1994, began testifying in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Monday, April 22, 2013. Following a week-long break in hearings due to the Khmer New Year holidays, it initially appeared that the Trial Chamber might be unable to resume hearing testimony, with Mr. Rin posing significant resistance to answering any questions at the outset, citing poor health and requesting the Trial Chamber for a medical examination or for assistance with his circumstances at Prey Sar. However, under the pressure of dogged questioning, Mr. Rin finally relented. By the end of the day, he was offering the Chamber detailed testimony in response to questions from the prosecution on a wide range of issues, most notably the role of Nuon Chea, purges of internal enemies, the battle between the Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol forces, and the evacuation of Kampot town.

Nuon Chea’s Participation in Light of His Health Issues

All parties to the proceedings were present this morning, Trial Chamber Greffier Duch Phary noted, except for accused person Nuon Chea, who was observing the proceedings from his holding cell in light of his health concerns. Cambodian attorney Moeun Sovann was also in attendance as duty counsel for Mr. Rin.

Seated in the ECCC public gallery were some 500 villagers from Kampong Chhnang province as well as Preah Vihear province, the site of the Temple of Preah Vihear, currently the subject of hearings at the International Court of Justice. Many of these villagers appeared to have been born during or before the Democratic Kampuchea (DK) period. In addition, it was reported that many victims and civil parties were also in attendance at today’s hearings.

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn advised that the Trial Chamber was seized of a medical report from one of Mr. Chea’s treating physicians. This physician noted that, while Mr. Chea’s health was stable, due to his lower back pain it was advisable that he participate in proceedings from his holding cell. This was consistent with the Trial Chamber’s April 8, 2013, ruling in this regard, the president said, which the Trial Chamber would maintain. However, President Nonn noted, if Mr. Chea’s health concerns changed, the Trial Chamber will advise accordingly.

Witness Chhouk Rin Gives Lengthy Opening Remarks Concerning His Health Issues

At this juncture, the witness Chhouk Rin alias Sok took the stand, a sky blue scarf wrapped tightly around his neck. Under questioning from the president, Mr. Rin advised that he is 60 years old, lives in Kep province, and has five children. President Nonn reminded Mr. Rin of his right not to incriminate himself. He noted that Mr. Rin had requested the assistance of a duty counsel regarding his rights and advised Mr. Rin to feel free to consult his counsel in this regard.

Mr. Rin advised that he gave interviews at Prey Sar Prison to the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (OCIJ) on three occasions between 2008 and 2009. Asked whether he had re-read the records of OCIJ interviews prior to today, Mr. Rin proceeded to give a very lengthy answer. He began by noting that while he had initially written to the Court indicating his willingness to be a witness in the case, he subsequently wrote President Nonn indicating that he was no longer willing to do so due to health reasons, attaching relevant documentation to his letter. Nevertheless, prior to the Khmer New Year, Mr. Rin reported that he was approached from the ECCC’s Witness and Expert Support Unit (WESU) advising that he was still required to testify.

Mr. Rin explained that he was willing to participate but asked the Court for its assistance, as the food rations at Prey Sar Prison were insufficient, and he also had difficulties with his eyesight that prevented him from reading all the relevant documents well. Mr. Rin then expressed his unhappiness that he was unable to speak some words before accused person Ieng Sary died. He also requested the Court to release accused person Khieu Samphan as he was not a senior leader.

Returning to the subject of his health, Mr. Rin stressed that while he was willing to testify and was a devout Buddhist, he was in poor health, with a headache and throat issues and being at only “70 percent” of his capacity. He therefore requested the Court to provide him some support while in Prey Sar Prison, noting that his food ration was only 2,800 Cambodian Riels per day.[2] The witness finished that, unlike Mr. Chea, he was a person of “full responsibility” and was willing to speak freely.

International Senior Assistant Co-Prosecutor Keith Raynor rose at this point. Noting that Mr. Rin had been speaking for some time now, he suggested that the Trial Chamber might wish to rule immediately on the matters raised so that the Chamber could proceed with its questioning of the witness. Following this intervention, the Trial Chamber judges huddled in conference.

President Nonn then advised Mr. Rin that the reason the court had not responded to his request was that the importance of the witness’s testimony “superseded” the request, and the Chamber had not received any reasonable evidence supporting Mr. Rin’s request to withdraw his consent to testify. The Trial Chamber was convinced that Mr. Rin, being an articulate man, could do his best and ensure that the proceedings involving him concluded expeditiously. The president also requested Mr. Rin to advise if at any point his health issues made it difficult for him to continue. The president concluded by commenting that even if Mr. Rin said something that was “perhaps not very relevant to the truth,” he believed that the Iron Genie[3] would not be very harsh towards Mr. Rin, given that much time had passed.

President Nonn then granted the floor to National Co-Counsel for Nuon Chea Son Arun. Mr. Arun expressed his concern that Mr. Rin’s health concerns might make him disoriented. He suggested that Mr. Rin’s health be checked by a treating physician before he proceeded with his testimony. The president advised that this request was too late and should have been raised before the Trial Chamber had ruled upon this issue.

Frustrated Attempt by the Prosecution to Begin Questioning Mr. Rin

After this lengthy prelude, National Assistant Co-Prosecutor Song Chorvoin took the floor to begin questioning on the part of the Office of the Co-Prosecutors, noting that she would begin by eliciting details of his early days. Ms. Chorvoin noted that Mr. Rin had testified to the OCIJ that he had been ordained as a Buddhist monk.[4] Asked why he had pursued this ordination, Mr. Rin responded instead that he was being forced to speak even though he had already advised the Trial Chamber that he had not had an opportunity to read his OCIJ interviews. Leaning back in his chair and with his eyes seemingly closed, Mr. Rin advised that he therefore exercised his alleged right not to speak and instead requested that the Trial Chamber assist him first.

The president asked Mr. Rin how he wanted to be assisted, to which the latter indicated that he wanted a doctor to first check his health before he proceeded further. He stressed that he was not intending to hinder the proceedings and wished to tell the Trial Chamber everything he knew but that his health had been obstructing him in the past few years. He also claimed that Nuon Chea had, in the past, ordered Mr. Rin to do things even if he was feeling unwell and that he felt compelled to do so at the time for fear of being killed. However, he did not wish to be compelled now to testify when he felt that he was “mentally and physically” unwell.

This speech prompted the Trial Chamber judges to convene in conference around their communal translator, with Judge Silvia Cartwright appearing to peruse a document. After several minutes, Ms. Chorvoin requested and was given the floor. She advised that the OCP wished to make some submissions before the judges ruled upon this issue. As a witness, Ms. Chorvoin said, Mr. Rin was required to answer some questions, and her initial question was not an incriminating one. Noting Mr. Rin’s stated difficulty with his eyesight, she suggested that a person be permitted to read the records of his OCIJ interviews to him before he continued with his testimony.

Mr. Arun responded that whether or not someone was permitted to read the OCIJ interviews to him was irrelevant; the issue was whether Mr. Rin was well enough to proceed with his testimony. Ms. Chorvoin requested a right of reply, but the president declined, noting that her earlier submissions were sufficient.

The president turned his attention to the witness and requested to know whether Mr. Rin had been feeling unwell before he came to testify. Mr. Rin responded that his throat felt unwell and his neck was very stiff. He indicated that he did not wish to disturb the proceedings and therefore suggested that the Chamber proceed with its reserve witness and Mr. Rin return at another time when he was feeling better and had been able to read the relevant documents. He requested the president to treat him properly and assured that he would return in due course and when fit to give concise and clear testimony.

President Nonn brought the witness’s attention to the apparent change in Mr. Rin’s cooperation since the time of his OCIJ interviews. In the interview records, Mr. Rin had indicated that he was happy to give a full account of his experiences during the DK period, although he later submitted a letter requesting to withdraw his witness status in light of his ailing health. However, President Nonn continued, the Trial Chamber had already noted the importance of Mr. Rin’s testimony, particularly on the subject of military structure, since the witness had served in the army since 1970.

The president requested Mr. Rin to advise precisely where he was living, which Mr. Rin indicated to be Prey Sar Prison. Asked in what capacity he was living there, Mr. Rin advised that he was there as a convicted criminal and had been sentenced to life imprisonment by the Cambodian Court of Appeal. According to Mr. Rin, he has been serving his sentence at Prey Sar Prison for over 10 years.

Given the floor to address Mr. Rin, Judge Cartwright noted that the witness had been speaking for almost one hour at this point, during which time he would have been able to provide some useful information. She advised Mr. Rin to stop wasting the Court’s time and start responding to the questions posed to him because he was required to do so unless the questions tended to incriminated him. The ECCC treating physician would monitor Mr. Rin’s medical condition while he was in the Court, she stated, but the ECCC did not have the power to provide Mr. Rin with any further medical assistance, which was the case with every witness. If Mr. Rin was tired, however, she concluded, the Trial Chamber would consider granting the witness a break if needed.

Witness Again Refuses to Respond to Questions, Prompting a Debate between the Parties

Judge Cartwright then directed Ms. Chorvoin to continue with her questions and Mr. Rin to listen to them carefully and attempt to respond to them. It was “very clear that not everyone in this courtroom wants you to speak,” the judge continued, but the judges on the bench did and requested him to do so. Ms. Chorvoin resumed her questioning after this lengthy interruption, asking the witness how old he was when he was ordained as a monk. Mr. Rin truculently responded that he could remember this answer but would not respond until his health had been checked.

At this point, Mr. Raynor said that the Trial Chamber “was not here to bargain with Mr. Chhouk Rin.” Mr. Rin had a duty to respond to the question, and his behavior this morning suggested, in common law terms, that he was a “hostile witness.” The prosecutor suggested that at this point, the only way to treat Mr. Rin was to read the witness the records of his OCIJ interviews and limit the witness’s answers to indicating whether these statements are right or wrong.

Lead Co-Lawyer for the civil parties Elisabeth Simonneau Fort endorsed Mr. Raynor’s suggestion. She also noted that of the many people present in the public gallery, there were also victims and civil parties who were as tired as Mr. Rin and who were nevertheless waiting to hear what Mr. Rin knew. He had a legal and moral duty vis-à-vis the people present to respond to these questions.

For his part, International Co-Counsel for Nuon Chea Victor Koppe noted that it was clear that Mr. Rin drove a “hard bargain.” However, he disagreed with Mr. Raynor that Mr. Rin could only be asked whether his responses in his OCIJ interviews were right or wrong. The witness also has the right to remain silent in order to avoid incriminating himself, Mr. Koppe asserted, and the Trial Chamber needed to respect this right. National Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Kong Sam Onn added that Mr. Raynor’s suggested questioning approach did not appear to be in conformity with the ECCC Internal Rules.

Mr. Raynor responded that the OCIJ interviews were on the case file, and the proposed form of questioning was consistent with the president’s question to the witness as to whether he had read the records of his OCIJ interviews and agreed with their content. “Be it on [Mr. Rin’s] head,” Mr. Raynor concluded, if he then chose not to respond to them.

This exchange prompted a third conference between the judges. After some minutes, the president advised that the prosecutors could proceed with their questions.

Another Prosecutorial Attempt at Questioning Flounders

At this point, Mr. Raynor took over questioning on the part of the OCP. Adopting the approach he had proposed, the prosecutor advised Mr. Rin that he would be putting to him various statements contained in records of his OCIJ interviews concerning interviews that took place on April 9, 2008,[5] and July 29, 2008.[6] The prosecutor began by noting that in the first interview, Mr. Rin had stated that he was angry when Mr. Chea said he was not responsible for anything that happened during the DK period, as “he was a high-level cadre.”[7] Mr. Raynor asked the witness why he was angry at Mr. Chea.

Addressing the president instead, Mr. Rin said that he had not “given up” as a witness. He did not want Mr. Raynor to simply read passages from the records of his OCIJ interviews instead of permitting him to speak freely. He simply wanted a delay in being summoned to testify, but now, he said, everyone was blaming him. He was being treated “as an animal,” he asserted, and he challenged that everyone should consider who was at fault here; was it the Chamber, or perhaps the head of Prey Sar Prison? He asked the president to forgive him, noting that while the Court knew about his health problems already, it had refused to have mercy on him.

The president responded that Mr. Rin did not want to help and instead insulted the Trial Chamber and questioned whether this refusal stemmed from Mr. Rin’s life sentence. President Nonn stressed that the Chamber understood Mr. Rin’s health problems, and thus sought to strike a compromise, with the OCP reading the statements Mr. Rin had already given to the OCIJ. Evidence was not valuable if it was just stored in the case file, the president advised, but needed to be discussed in the Chamber.

Mr. Raynor then added that in a trial in 2010, he had examined a hostile witness for two and a half days, which proved to be a “painful exercise.” However, he noted, it was his duty to put to the Court the statements Mr. Rin had made to the OCIJ. If Mr. Rin chose to make the exercise a painful one, that was his choice, the prosecutor concluded; Mr. Rin could answer in the way he wished, though Mr. Raynor requested the president to intervene if the witness’s answers were repetitive.

Undeterred, Prosecution Begins Putting to Witness Extracts of His Statements to the OCIJ

Moving on, Mr. Raynor said that in April 2008, Mr. Rin had testified that it was not true that Mr. Chea “did not know.” The prosecutor asked the witness to clarify what this statement meant. Mr. Rin, leaning back in his chair, said that the prosecutor could read, and continue reading, but Mr. Rin would just listen. Persisting undeterred, Mr. Raynor read that, concerning the decision to purge the East Zone, Mr. Rin had said to the OCIJ investigators:

[This] decision was made after the Party annual general assembly in 1978, with Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ta Mok, and Son Sen holding a special meeting with military commanders including myself in Phnom Penh. Pol Pot spoke about the plan to purge. Then Nuon Chea agreed with what Pol Pot had said. Nuon Chea and Pol Pot supplied detailed information on the plans to arrest and remove the cadres from the East Zone.[8]

Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin how much detail Pol Pot and Mr. Chea supplied. In a soft voice, Mr. Rin simply responded, “You just read.” The prosecutor then said that, in his next OCIJ interview, the witness had testified that there were many meetings about this plan. Mr. Rin had elaborated in the interview that he been asked to return to Phnom Penh to attend a special meeting with top leaders to discuss the purge of the eastern cadres. There were approximately 600 to 700 people present, including Meas Muth, as well as senior Khmer Rouge leaders Pol Pot, Ta Mok, Mr. Chea, and Son Sen. According to his OCIJ testimony, Mr. Rin had said that during this meeting, Mr. Chea spoke of the need to purge the “internal enemy.”[9] Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin whether this was correct, to which the witness responded with a lengthy silence, followed by a quiet command for the prosecutor to continue reading.

On this same topic, Mr. Raynor said, the witness had also testified that at about the same time as the Party’s annual general meeting, there were separate meetings for the military commanders and the civil side. Mr. Rin had testified that around 20 divisional and regimental commanders had been in attendance at the meeting he attended for the military. Pol Pot spoke first, followed by Ta Mok, who spoke about the necessity of the internal purge of the party, while Nuon Chea spoke of the importance of cleansing the Party ranks.[10] Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin whether this was what Mr. Chea said. Mr. Rin simply advised Mr. Raynor, in a low voice, to continue reading.

According to one of the records of Mr. Rin’s OCIJ interviews, Mr. Raynor continued, Mr. Chea had spoken of the need to purge internal enemies who were the “arms and legs of the Yuon.”[11] Mr. Chea had ordered the “arrest,” meaning the purge; the record noted that in that era, the term “purge” meant to arrest and kill.[12] Mr. Raynor asked whether this was correct. In a low voice, Mr. Rin told Mr. Raynor to go ahead and read more.

According to one of the records of Mr. Rin’s OCIJ interviews, Mr. Raynor continued, Mr. Chea had spoken of the need to purge internal enemies who were the “arms and legs of the Yuon.”[11] Mr. Chea had ordered the “arrest,” meaning the purge; the record noted that in that era, the term “purge” meant to arrest and kill.[12] Mr. Raynor asked whether this was correct. In a low voice, Mr. Rin told Mr. Raynor to go ahead and read more.

The witness had also testified to the OCIJ that Pol Pot frequently spoke of the necessity of purging and Mr. Chea spoke of “internal enemies.”[13] Mr. Raynor asked the witness how often Mr. Chea spoke about internal enemies. After a lengthy silence, Mr. Rin advised, with a seemingly long suffering face, that the prosecutor keep reading the records of OCIJ interviews, “because everything is in there.” On this note, the president adjourned the proceedings for the mid-morning break.

Defense Challenges Questions on the East Zone

After the hearings resumed, the president ceded the floor to International Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Anta Guissé. She noted that Mr. Raynor had been discussing the purge of the East Zone, adding that while the parties did not yet have the Trial Chamber’s written decision concerning the new scope of Case 002/1, she did not believe this topic to have been included within it.

Mr. Raynor responded that this issue had come up on several occasions and that “countless” witnesses had already come before the Trial Chamber and been permitted to give limited testimony about the purge of the East Zone since this testimony illuminated the administration and communication structure during the DK period, that is, how the leaders “ran the business of [the] DK.” It was also relevant, the prosecutor added, because it showed Mr. Chea’s role and indeed went to the heart of what the OCP argued to be the policy of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), pre-dating the DK period, to purge internal enemies within the Party.

Moving on, Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin whether it was correct that he wanted to tell the world about what happened during the DK in his own words. Mr. Rin responded that Mr. Raynor had said a lot and it was “too much” for him to respond to Mr. Raynor, as he was not very well. He requested the president to give him a rest as he could take no more. Mr. Raynor suggested that the president be “very, very careful” about this request, given the delicate juncture of this trial and what was going through Mr. Rin’s mind given his demeanor this morning. Granted the floor, Mr. Koppe said that it was irrelevant and indeed impossible to determine what was going through Mr. Rin’s mind.

The president directed Mr. Raynor to continue with his questions to Mr. Rin. Mr. Raynor duly asked the witness to elaborate on his testimony that Mr. Chea had ordered him to carry out a purge of the East Zone. Mr. Rin advised that as he had a headache, he had advised his duty counsel Mr. Sovann to record the questions Mr. Raynor put to him, and he would respond to those questions when he was feeling better. This response prompted President Nonn to ask Mr. Rin whether he had been examined during the mid-morning break. Mr. Rin confirmed that two treating physicians had done so. The president noted that Mr. Rin had reported having a headache and feeling unable to sit at length but that the treating physicians could not substantiate this claim.

Witness Reluctantly Offers Details on Co-Accused, Communications, and “Internal Enemies”

Before continuing, Mr. Raynor quipped to Mr. Rin that he “was not the first witness who has had a headache from my questions.” The prosecutor then returned to Mr. Rin’s statements to the OCIJ. He noted that, according to those statements, Nuon Chea had been deputy secretary of the CPK since 1973 and that for someone to join the party, that person had to know the roles of the Party and the Party leadership.[14] Mr. Raynor asked whether this was correct. In a small breakthrough, Mr. Rin engaged with this question and confirmed that it was correct.

Allowed to hand the witness copies of his OCIJ statements, Mr. Raynor noted that Mr. Rin had testified meeting Mr. Chea for the first time in late 1977 at the CPK’s annual general meeting.[15]When asked whether this was correct, Mr. Rin advised that he thought the OCP had already conducted investigations on this matter and that he could not confirm it as he was not wearing eyeglasses. Mr. Raynor assured the witness that if he spoke incorrectly, his duty counsel would surely advise him of this.

According to Mr. Rin’s testimony, Mr. Raynor said next, at the 1977 annual general meeting, Mr. Chea had announced that Kang Chap and other high-level cadres had been arrested.[16] Mr. Raynor asked who else had been arrested. Mr. Rin advised that this announcement had been made in 1976, not 1977, but did not offer any further names of arrested cadres.

Staying on the topic of the East Zone purge, Mr. Raynor referred Mr. Rin to his previous testimony concerning a meeting at Ta Mok’s house, in which the witness had stated:

Before a cadre purge mission in the Eastern Zone, the military commanders and I were called in mid-1977 to attend a meeting at Ta Mok’s home in Takeo. The meeting was urgent, and was held for one day. There were 700 soldiers from Kampot, 1,000 from Takeo, and 700 to 800 from Kandal. A day after the meeting, we were sent to Phnom Penh.[17]

Mr. Raynor asked whether this was correct. Mr. Rin disagreed and said that the soldiers were sent to the East Zone, not Phnom Penh.

The accused person Mr. Samphan was the subject of Mr. Raynor’s next line of questioning. Noting that the witness had testified that he did not know much about Mr. Samphan,[18] the prosecutor asked whether this was correct. However, before the witness could respond, Mr. Koppe objected that as it appeared the witness was changing his position and was now answering questions, the OCP should now be asking the witness open and not leading questions.

Mr. Raynor advised that as Mr. Koppe was not representing Mr. Chea last year, he could not be expected to know about the extensive discussions on this topic nor that the Chamber had ruled that where the witness had made a statement, it was acceptable to take the witness to the relevant passage in that statement and ask questions concerning it, stressing that this was something that the prosecution had previously been permitted to do. Mr. Koppe, granted a right of reply, stated that this was a “court of law” and asking such yes or no questions was not permissible in such a court. The president disagreed, however, and directed Mr. Raynor to continue with his line of questioning.

The prosecutor stressed to Mr. Rin that he was permitted to indicate if the previous statements he had made before the OCIJ were correct or not. Noting that the witness had previously testified that he had never met Mr. Samphan,[19] Mr. Raynor asked whether this was correct. Mr. Rin confirmed this. The prosecutor then advised that according to Mr. Rin’s past testimony, Mr. Samphan had been a member of the Front with the late King Father Norodom Sihanouk and the CPK had used Front members as diplomats for communicating with the world.[20] Mr. Samphan could be seen listening impassively to this question, while Mr. Rin was seen perusing a document with his duty counsel.

After some moments, Mr. Rin advised the prosecutor to continue reading. Mr. Raynor asked the witness whether he knew Mr. Samphan’s role in the Front. The witness responded instead that he had again instructed his duty counsel to write down all the questions as he had a headache. Mr. Koppe noted that he could see Mr. Sovann writing things down on a piece of paper and Mr. Rin looking over this paper. The defense counsel protested that this was not proper procedure, and he asked the president to intervene. The president advised Mr. Rin to wear eyeglasses to read what Mr. Sovann was writing. Mr. Rin said that he needed to wear “300 degree” eyeglasses but did not have them. The president duly asked the court officer whether he had such eyeglasses. The court officer confirmed this and the president therefore directed that the witness try the eyeglasses.

At this point, Mr. Koppe clarified that his concern was with Mr. Rin reading what Mr. Sovann was writing, which was a practice that should not be allowed at the ECCC. The president duly advised that Mr. Sovann was not permitted to continue with this practice but had to wait for questions that could incriminate Mr. Rin. If there were no such questions, he stated, Mr. Sovann should remain silent. President Nonn then directed Mr. Rin to wear the eyeglasses and attempt to read the relevant text. If he could not do so, Mr. Raynor would be permitted to read extracts to him, he concluded.

Mr. Raynor advised that he did not want to read passages to Mr. Rin as he wanted to give the witness a chance to speak his mind. Mr. Raynor then asked Mr. Rin whether he thought that Mr. Samphan was a member of the Party Center. Mr. Sam Onn objected to this question, at which point Mr. Raynor laughed heartily and leaned over his lectern, arguing that it seemed he could not get it right; either he was being criticized for asking leading questions or for asking open ones, which he had now been striving to do in the spirit of Mr. Koppe’s earlier objection.

Continuing to lean over the lectern, Mr. Raynor advised that the essence of his question was what Mr. Rin knew or observed Mr. Samphan’s role. Ms. Guissé advised that the difficulty could be solved by asking what Mr. Rin knew or did not know of something, rather than what he thought about something. The president advised that Mr. Raynor’s question was acceptable in its changed form and directed Mr. Rin to answer it. The witness protested that while he had asked not to answer questions, the OCP was persisting with its questioning anyway.

This response led the prosecutor to put the question a different way, asking what Mr. Rin knew of Mr. Samphan. Mr. Rin again stressed that while he did not object to testifying, he was unable to do so at this time as Mr. Raynor’s questions were giving him a serious headache. Mr. Rin then volunteered that during the DK regime, there was a document stating that Mr. Samphan was a leader “without any real power.” Therefore, he requested that Mr. Samphan be released. Mr. Rin added that he was unable to give any more details, but proceeded to offer them anyway, advising that he had heard Ta Mok say that Mr. Samphan was “an intellectual and … a leader without any real power. There was only one party: the CPK, which was responsible for everything.” However, Mr. Rin was unable to elaborate further, he continued to assert, because of his serious health problems.

Mr. Raynor interrupted at this point, observing that Mr. Rin had been speaking for three minutes very eloquently and without interruption. He asked the witness to advise if his headache incapacitated him for more than three minutes. He then asked whether Mr. Rin had ever heard of the Standing Committee and the Central Committee during the DK period. Mr. Raynor said that he did not want Mr. Rin to speak necessarily for three minutes on this question, as it was a simple one. He then repeated his question. Mr. Rin advised that he did not understand this matter as he was a “low-level soldier.” The prosecutor asked whether the witness had ever heard the phrase “the Center” in relation to the senior leadership. Mr. Rin responded, simply and cryptically, “I know.” Asked to elaborate, Mr. Rin advised that “[h]e spoke in accordance with what is written.”

Mr. Sam Onn objected again at this point, suggesting that Mr. Raynor was leading Mr. Rin, as he had not asked Mr. Rin whether he had attended a meeting regarding such a matter yet. With no response forthcoming from the bench, Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin whether he knew if Mr. Samphan spoke at meetings of the Center. Mr. Rin advised that he did not see Mr. Samphan making any speech “in the CPK.” Mr. Raynor advised that this response did not answer his question, and repeated his question again. Mr. Rin replied, “If the question is beyond what I said earlier, I will not give a response.”

Khieu Samphan (right) meets with members of the Burmese embassy during the DK period.

(Source: Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Persisting, Mr. Raynor asked the witness another question on this matter, which he said was to see if Mr. Rin had been following the Case 002 trial from Prey Sar Prison. Mr. Raynor’s question was whether the witness knew if Mr. Samphan had been a full-rights member of the Central Committee. Mr. Rin denied ever making this statement. Mr. Raynor clarified that he was not suggesting that Mr. Rin had said this and continued by posing a more elaborate question, asking Mr. Rin whether he was aware, from reading documents or speaking to people, whether Mr. Samphan ever told the OCIJ that he was a full-rights member of the Central Committee. Mr. Rin said that he did not know about this matter, and, in reference to Mr. Samphan, who was present in the courtroom, stated, “You [should] ask him. He is over here.”

Shifting to a new theme, Mr. Raynor asked whether the witness recalled if there had been radio broadcasts or celebrations around April 17, 1976, 1977, and 1978, to celebrate the anniversary of the liberations around the country. Wiping his furrowed brow, Mr. Rin said that he remembered these occurring but did not remember the dates. Pressed as to whether he remembered speeches being made, Mr. Rin said that he had forgotten. Shifting to the topic of telegrams, Mr. Raynor read out Mr. Rin’s testimony to the OCIJ:

I never saw signatures, but there were identification numbers. For example, Pol Pot was 99. Ta Mok was 15. … But I don’t remember the identification numbers in the telegrams. I personally saw the telegrams. They read the telegrams at the meeting sites.[21]

Mr. Raynor asked what kinds of “meeting sites” Mr. Rin had been referring to here. The witness asked the prosecutor to continue reading. Mr. Raynor advised that he was interested in who read the telegrams at the meeting sites, which had not been covered in the interview. Mr. Rin said that he did not remember, because he had not reviewed the record of the OCIJ interview yet. He thus advised Mr. Raynor to simply continue reading. The prosecutor heeded the request and read further OCIJ testimony of Mr. Rin:

I received and issued almost all military orders through a shoulder-carried radio in the battlefield. We could contact Phnom Penh from Svay Rieng province. We used the radio many times a day, and I changed my code number frequently.[22]

Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin whether this was correct. The witness confirmed this was so. Next, the prosecutor asked the witness to elaborate on the meaning of the term “sweeping up.” Mr. Raynor noted that Mr. Rin had previously testified:

“Sweeping up” meant a lot of things. Firstly, any person who was bad would not be allowed to join the CPK and would be dropped from the CPK membership and watched. Secondly, when there was a suspicion, that person would be arrested. The term “drop” meant not [being] allowed to join the party. The term “smash” meant arrest and kill. For example, people in the Eastern Zone were purged. The maximal purge was a thorough clean-up of the Party line. The “April 17” people were considered to be with the enemy, so they were segregated. The term “purifying the army” meant making the army clean.[23]

The prosecutor asked whether this was correct. Mr. Rin directed Mr. Raynor to continue reading, but the latter persisted on this point, insisting to know whether it was right. The witness eventually conceded that it was. The prosecutor then asked why “April 17” people were considered the enemy. Mr. Rin responded, “This is beyond my understanding as I did not know anything about the planning of the CPK. As a soldier, my task was to defend the country.” Mr. Raynor asked who told Mr. Rin that this was his task. Mr. Rin said that “in general, everyone in Cambodia would know this.”

Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin when he was first told that “April 17” people were the enemy. Mr. Rin advised that he could not recall. At this point, the president adjourned the hearing for the lunch break.

Dam Breaks: Witness Begins Giving Extensive Testimony on Internal Enemies and Purges

After lunch, and before he resumed his questions, Mr. Raynor noted that as Mr. Rin’s requests during the morning resulted in the loss of one hour of questioning time, he requested that the OCP be granted a further one hour of questioning time during the morning of the hearing on Tuesday, April 23, with the Lead Co-Lawyers for the civil parties being permitted to ask their questions after the OCP had concluded. The president granted this request.

The prosecutor returned to the topic of “April 17” people being enemies, Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin who spoke to him about this matter. However, before Mr. Rin could respond, Mr. Sam Onn objected, requesting Mr. Raynor give a specific reference for this statement. Mr. Raynor said that he was referring to the statement of Mr. Rin to which he had previously referred. Turning to the witness, Mr. Raynor gave the witness some chronological details, noting Mr. Rin had joined the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea (RAK) in 1971 and was a platoon commander in 1973. He asked when Mr. Rin received this information. The witness responded:

These people who were Lon Nol soldiers were regarded as “April 17” people, [but] I never received any instructions [to this effect]. These people who had been with the enemies, they were in the liberated zone, and later on, they were considered as “April 17” people.

Trying to make headway with the witness on this point, Mr. Raynor asked whether he had lived in the liberated zone from 1971 to 1975. The witness expressed confusion over this question and requested the prosecutor to repeat it. By way of assistance, Mr. Raynor noted that in one of the witness’s interviews, Mr. Rin had stated that “[i]n 1971, I joined and served the CPK through Sien, the chairman of Kampong Trach district.”[24] Mr. Rin confirmed, when asked, that this was correct and that he also become a commander of a platoon in the Kampot sector[25] by 1973.

Mr. Raynor noted that the zones under Khmer Rouge control were believed to be known as the “liberated zone, querying whether this was indeed the term used. The witness confirmed this. He also confirmed that areas that were not under Khmer Rouge control were considered to be “occupied by enemies.” Thus, Mr. Rin confirmed when asked, that between 1971 and 1973, he understood that people who occupied areas not under Khmer Rouge control were considered “enemies.”

Building on this line of questioning, Mr. Raynor asked who else was considered to be enemies of the CPK. In an OCIJ interview question concerning Revolutionary Flag magazines, Mr. Rin had testified that “not only were feudalists and capitalists purged but also the farmers who owned the rice fields: they were also the enemies of the CPK.”[26] Mr. Raynor asked whether this was correct. Mr. Rin advised that this question was long and confusing. Mr. Raynor therefore asked the witness what happened to farmers who owned their own rice fields during the DK period. Mr. Rin responded:

During the time when the country was under the control of the Khmer Rouge leaders … in the relevant Revolutionary Flag number seven, in study sessions, we were lectured on the danger we would face. We were advised not just to be afraid of the “April 17” people but to be … cautious regarding the people in the government because the government reflected information about spies, including Vietnamese spies and KGB Russian agents. I believe that my superior, who is here [in the courtroom], is who this referred to. We were also lectured about CIA agents. …

In the army where I served, a lot of senior leaders of the army were arrested. I still cannot understand who could have been a KGB or CIA agent or spy. I still don’t understand, even if my colleagues in arms were arrested, some of the senior leaders of the battalions and companies were arrested by their peers. … Even Khmer Rouge soldiers or soldiers of the DK were terrified by this ordeal. The purges were carried out every now and then. I could see very clearly that some senior military leaders were arrested. Nonetheless, we were not allowed to know what had happened at the base. The only thing I knew very well was that persecution was being inflicted upon Cambodian people.

We learned about the problem also through the document Revolutionary Flag number seven. I also heard about Mr. Khieu Samphan through what I heard through Ta Mok. Ta Mok said that Khieu Samphan was an intellectual who was not deeply engaged in the CPK. I also told the Court that I am not willing to speak the details at this moment because I am now on medication. I have to use some paracetamol to relieve my headache.

Mr. Raynor interjected at this point, thanking the witness for that “very helpful” answer. He then noted that in the same interview, Mr. Rin had stated that “in 1975/6, Sambit ordered the arrests of those in the army. In 1975, a number of the commanders of the battalion and of the regiment were arrested and charged, so the army was purified from the beginning.”[27] Mr. Raynor asked whether this meant that the army was purified from 1976. Mr. Rin confirmed that this was so and that when he came to study sessions in Phnom Penh, he saw Pol Pot and Mr. Chea. He then elaborated:

The internal situation at that time was dire because internal disputes were rampant in the party, and this led to arrests of people in Kampot province. Also, soldiers in Kampot and Takeo were gathered and sent to the East Zone so that they could engage in the battlefields. But they were fighting their own people.

Mr. Raynor noted that, according to Mr. Rin’s testimony to the OCIJ, some people were then arrested and sent either to Phnom Penh or to Kampot. Mr. Rin confirmed that this was a true account of events in the East Zone.

At this point, Mr. Raynor turned to the subject of the Kampot security office. The prosecutor asked Mr. Rin whether this office existed before the evacuation of Kampot in April 1975. The witness advised that he did not know this exactly but this was consistent with “the overall situation at that time.” On this point, Mr. Raynor noted that Mr. Rin had previously testified to the OCIJ that the Kampot office “was part of the security office of Sector 35 in Kampot, where only military prisoners were imprisoned. It was not for civilian prisoners.”[28]

However, before the witness could comment on this statement, the president granted the floor to Mr. Koppe. The defense counsel advised that he sought some clarification from the bench as this was a “very leading question,” although it was indicated this morning that such questions were allowed. Mr. Koppe asked the president whether he should continue to object or not. He wished to avoid the Supreme Court Chamber deciding that the defense should have objected to the matter when it arose and not appeal about it after the fact.

After a moment of inactivity, the Trial Chamber judges convened. After a few minutes, the president advised that Mr. Raynor’s last question concerning the Kampot security office was leading in nature and therefore Mr. Rin need not answer it. Next, he said the Chamber listened to each line of questioning and ruled on each objection “on a case-by-case basis” consistent with the procedural rules of the civil law system, which the parties should have been used to at this point. He advised that parties could object from time to time on any seemingly objectionable lines of questioning, adding that there may have been some issues with respect to questioning during today’s hearing in light of Mr. Rin’s change of attitude towards answering questions.

Following this objection, Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin when he first knew that there was a security office in Kampot. Mr. Rin said that he did not know its “exact location” but only that “people were arrested and put in the security center; a number of soldiers were arrested and sent to that security center.” However, he “was not told of that place” at the time. Mr. Raynor clarified, with some apparent frustration, that he did not ask Mr. Rin about the center’s location but the time at which he found out about its existence. Mr. Rin advised that he only learned about its existence “after the arrest of my direct superior.”

Questions on CPK Teachings in Revolutionary Flag Number Seven

Moving on, Mr. Raynor noted that in one of Mr. Rin’s interviews, the witness had said, “The term ‘get rid of’ in this sentence meant that if we did not follow any assignment, we were not their people. In a refashioning meeting, those who did not succeed in fulfilling an assignment would be declared as enemies.”[29] Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin for some examples of this. Mr. Rin noted that in the Revolutionary Flag number seven issued by the CPK in 1976:

[The Party] described the different types of people, for example people who plowed fields and broke the plow. These people would be alleged as enemies. If anyone would break even one spoon or one plow, this person’s position was not certain; the person would [be considered] not inclined to follow the Party line.

Mr. Raynor also noted that at the same part of the OCIJ interview, Mr. Rin stated that if someone made a mistake, they would need to be arrested under an order “from the top.” Asked for an estimate of how many people were arrested after April 1975, Mr. Rin advised, with somewhat more enthusiasm:

I can only confirm that there were arrests of military commanders at that time. My former superior was a Communist believer and follower, and he was also arrested. The leaders of the CPK summoned us to attend training courses in Phnom Penh. We dared not ask even one question. …

We came to attend a training course, and Revolutionary Flag number seven was the material for training at that time. The trainees were supposed to discuss the issues in the study materials, but we dared not discuss each other’s personal affairs. For example, if Mr. A was arrested and people continued to talk about the arrest of this person, this could create an atmosphere of distrust in the team. We were not supposed to discuss [such an arrest].

My former direct boss might not agree with what I said, but that was what I believed at that time. … I only followed the appeal by the then Prince Norodom Sihanouk following the coup d’état. At the time, we felt unhappy with Lon Nol, and we joined the resistance.

Mr. Rin advised, when pressed, that he only attended training on one occasion, providing the following details:

When the situation along the border got worse, I was sent there. We received instructions from the upper authority to reinforce the forces along the Cambodian-Vietnamese border, particularly in Svay Rieng province. I would only like to bring up the chain of stories at that time. At that time, the Khmer Rouge cadres were afraid of making mistakes themselves. … Everyone had to be vigilant. …

Before I joined the resistance forces, I did not know who Pol Pot was, I only knew Mr. Nuon Chea. I was summoned to a training, and they told us about Prince Norodom Sihanouk. We did not hear about Mr. Khieu Samphan. … I feel very, very sorry that some prominent people, like Prince Norodom Sihanouk, were being cheated by Mr. Chea at that time. When we deviated, we could not get out of it ourselves. We were drawn deeper into it. We were tools of the Party. Whatever the Party directed us, we had to follow. We had no choice. We at that time had to follow instructions. My former boss may not agree with what I am saying now … but at that time … we killed ourselves. We killed each other among our forces.

Mr. Raynor asked the witness who wrote the policies published in Revolutionary Flag number seven. Mr. Rin responded:

At that time, the leaders of the CPK were mysterious. … We at that time were very frightened; we were in constant fear. We rarely met those leaders either. We studied based on the CPK materials. We knew that the leaders of the CPK were there. There were many survivors who survived the fighting. I believe that the Court might find out more about those survivors, who can be very helpful to ascertaining the truth of the history of Cambodia.

This response prompted Mr. Raynor to remind Mr. Rin that when he was questioned by the OCIJ, Mr. Rin had said that the authors of the policy in Revolutionary Flag number seven were:

The persons from the Central Committee, such as Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, and Ieng Sary, who copied a little of the idea from the Russian Communist Party, and from China. However, the main ideas were theirs, because as long as they agreed within the party, then the principles could be adopted and implemented throughout the country.[30]

The prosecutor queried why Mr. Rin had made this statement. Mr. Rin said that it was because “we followed the instructions of the Party leaders. And who were the Party leaders? There were only those few. … They were the leaders of the CPK.”

Witness’s Comments on a Series of Military Documents

In light of Mr. Rin’s military experience, the prosecutor was granted permission to ask the witness questions concerning a series of military documents. The first document, a neatly typed table, was entitled A General Staff Study Session, and the session itself was held on November 23, 1976.[31]This table, Mr. Raynor said, showed the participants in the study session. The attendees included people sent from nine divisions: Divisions 450, 801, 502, 703, 170, 290, 164, 310, and 920. Mr. Raynor advised that according to the witness’s testimony to the OCIJ, in May 1975, he became artillery commander of Battalion 59, subordinate to Kampot province, where Mr. Rin was the Kampot sector commander. Mr. Raynor asked the witness whether he knew the number of his division at that time. Mr. Rin advised:

There was only one battalion in the province. I could not remember … the number. I can just talk about my own small unit, [in which] there were over 300 [soldiers]. This is beyond my capacity. … This is about the general staff. I am a low ranking soldier. I do not understand this. I cannot respond.

Mr. Raynor accepted this answer and moved on. He noted that Mr. Rin had testified about becoming a platoon commander in Battalion Koh, supervising 36 soldiers. Mr. Rin confirmed this was correct. The prosecutor noted that Mr. Rin had detailed to the OCIJ investigators the existence of three battalions in Kampot: Battalion Ka with Chey alias Sokhan as commander; Battalion Kar, with Chhorn as commander; and a third battalion with Chhorm as commander. The prosecutor queried whether this was correct, which Mr. Rin confirmed. As Mr. Rin had testified to the OCIJ that all three had been arrested, Mr. Raynor asked how the witness knew this. Mr. Rin advised that this was because “they were my direct superiors, and after they were arrested, I could not see them.”

Turning to a new topic, Mr. Raynor asked the witness when he first met Ta Mok. Mr. Rin said that he could not remember the date, only that “Ta Mok was the leader of the Southwest Army. I heard his name. He went to Kampot. I cannot give details.” Mr. Raynor asked whether the witness ever heard the name Thuch Rin. Mr. Rin confirmed this and said that “Rin was with me in Kampot.” Smiling, Mr. Rin advised that their names were different, indicating different pronunciations and that “Rin also disappeared.” Mr. Raynor asked whether the witness knew of a man named Praseth. Mr. Rin said that he had heard of his name but had never met him. The president then adjourned the hearing for the mid-afternoon coffee break.

Ta Mok (right) with Chinese advisor during the 1980s.

(Source: Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

Arrests of Internal Enemies and Lon Nol Soldiers, and an Alleged Killing of Vietnamese

After the break, Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin whether he had known of Chou Chet. Mr. Rin confirmed that Mr. Chet was his former superior. As to whether he knew Songha Hoeun, Mr. Rin denied this. Moving on, the prosecutor asked the witness where his platoon had been located. Mr. Rin stated that it would “take the whole day” to explain this, since under Khmer Rouge rule, platoons would not be stationed in one area for a long period of time but were instead constantly “on the move, without a permanent base.”

This prompted Mr. Raynor to ask the witness whether he had known at the time about a struggle in the Southwest Zone between Ta Mok and Chou Chet. Mr. Rin confirmed that “everyone knew” of Mr. Chet’s arrest, although not the reason for it. Next, Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin whether he knew what happened to Mr. Chet. The witness denied this.

Next, the prosecutor asked Mr. Rin whether, after he became a platoon commander in 1973, he was fighting Lon Nol soldiers. Mr. Rin replied:

I don’t remember all the locations where I engaged in combat, because I engaged in combat in almost all districts in Kampot. If you asked me what I did between 1970 and 1973, I can tell you that during this period of time, we were heavily bombarded by the Americans. The airplanes could be seen dropping bombs attacking us from the sky. Every district in Kampot would be affected by these bombs. You can see the craters created by these bombs dropped during that period of time. One of the pagodas in my hometown was completely destroyed by the bombs. Some monks were also killed because of the bombs, and some of them had to join the Khmer Rouge.

This is what happened during these early days, although I cannot recollect every detail of the accounts. As I have already asked for forgiveness, I may not fully cover the real account. When it comes to the battlefields, I can say that it is difficult to say where we engaged in the battlefields, because every field would be a battlefield, and we would engage in every single one.

Mr. Raynor asked the witness to confirm whether such combat after 1973 was with Lon Nol soldiers. Mr. Rin confirmed this and added that combat with Lon Nol soldiers continued up to 1975, when the war ended. This prompted the prosecutor to ask what happened to Lon Nol soldiers after they were captured by the CPK. Mr. Rin explained:

During 1973, we could not call the soldiers the soldiers of the CPK. They were known as soldiers of the liberation. Regarding the prisoners of war, we were instructed and advised by our superiors to detain these prisoners and have them sent to the rear. I don’t remember how many or who was arrested, because it was a very long time ago. These events happened in 1973, and during that time, our people were also arrested, and those people were arrested by us.

Mr. Raynor asked if there were camps where the Lon Nol soldiers were detained. Mr. Rin responded, smiling and examining his fingernails, that he was not aware of this. The prosecutor turned to query the witness as to the frequency of their capture. Again, the witness indicated that he did not know, adding that “it was not my knowledge that the soldiers could be arrested on a daily basis.” Pressing this point, the prosecutor asked the witness whether he ever spoke to fellow soldiers about this matter, which the witness denied. Mr. Rin added that “people were not arresteden masse until April 1975.”

Returning to the individual Chou Chet, Mr. Raynor asked whether the witness heard of any followers of Mr. Chet being arrested in 1973. Mr. Rin denied this, advising that he had only heard about Mr. Chet’s arrest. The prosecutor asked when Mr. Rin first heard of anyone being killed because they were an enemy. Mr. Rin advised, “Arrests happened more frequently in 1975. On top of that, my senior leaders in the province were good people. That is why such arrests were not made [in earlier days], and there were no disappearances other than casualties resulting from the bombings.”

The prosecutor instructed Mr. Rin not to think about Lon Nol soldiers with respect to the next question and proceeded to inquire whether Mr. Rin was aware of anyone in 1973 to 1975 being killed because they were enemies. Mr. Rin replied:

Immediately after the war was over, in Kampot province, all former soldiers had to be disarmed, and the entire city had to be evacuated. At that time, we did not know who could have been soldiers, people, or else. … Immediately after the war was over, we also had to be demobilized. We had to go back to our respective units, and the base was in charge of evacuating the people. If you would like to know more about who would have been in charge of the bases, you have to ask the people concerned instead.

Cutting the witness off at this point, Mr. Raynor explained that Mr. Rin had been starting to go into events after 1975. He noted that according to Mr. Rin’s testimony to the OCIJ, he had said that “the CPK carried out an inflexible policy of killing Khmer Vietnamese citizens from Hanoi. In 1973, they [the CPK] fought the Viet Cong situated on Khmer soil.”[32] Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin why he had told the OCIJ this. Mr. Rin said that he thought “this question may have been misleading. I said that the Khmer Rouge and the Viet Cong were divided [and thus the Khmer Rouge] engaged in fierce fighting with the Viet Cong soldiers.”

Mr. Raynor explained that he was not talking about fighting with the Viet Cong but about the CPK policy of killing Khmer Vietnamese citizens from Hanoi. Mr. Rin responded:

I think I did not say anything about this. … The only thing that I am clear about is that I talked about the fighting between Khmer Rouge soldiers and the Viet Cong soldiers. I never said anything about the killing of Vietnamese civilians, and I told the investigators about this because I was asked to tell them in detail about the fighting between [them]. This happened in Kampot province between Touk Meas and Tany districts.

At this juncture, Mr. Raynor requested that Mr. Sovann assist Mr. Rin in locating the relevant passage in the record of his OCIJ interview. The prosecutor then asked the witness what he knew about the CPK killing citizens from Hanoi in the period around 1973. However, before Mr. Rin could respond, Mr. Sam Onn objected that Mr. Rin had already indicated that there were no Vietnamese citizens from Hanoi who could have been killed or attacked by Khmer Rouge soldiers.

Slowly and deliberately, Mr. Raynor explained to Mr. Rin that when he had been questioned by the OCIJ, an audio recording of the interview had been made and the record of the interview was an accurate reflection of what Mr. Rin had said. Mr. Rin said that he believed he understood the question now and thought that it concerned “the Khmer citizens who went to Hanoi,” which the witness speculated may have occurred during the Khmer Issarak regime. When these people returned, Mr. Rin said, “they were arrested, and they were regarded as the Khmer Hanoi citizens.”

Mr. Rin suggested Mr. Raynor conduct a further investigation into this matter and added that he believed some documents relevant to this issue existed. Mr. Rin further noted that some of these people “became members of the Khmer Rouge” and some had survived the DK regime, although he conceded that the rest “perhaps have all disappeared, it is true.” Mr. Rin stressed, again, that this did not happen to Vietnamese people but Cambodian people who went to Hanoi to study and then returned to Cambodia. Furthermore, he did not think that “many of them” were so arrested. The witness could not, when pressed by Mr. Raynor, shed any light on why these people were arrested.

The prosecutor noted that Mr. Rin was discussing the fact that these people had been arrested but that he had testified to the OCIJ that these people had been killed. Asked about this, Mr. Rin explained:

As I said earlier, what interested me was what happened in the military. The Chamber may have understood that. After the end of the war, all soldiers could not come back to their village or commune. They had to stay at their position. They were not allowed to come back to the rear bases. If they came back, they were not given even rice to eat. That was what happened at that time … [although] I cannot give a detailed description.

The War in Kampot between the Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol Soldiers before 1975

The prosecutor commenced a line of questioning concerning artillery, noting that the witness had become an artillery commander in 1975. Asked if he had already been involved in artillery in 1973 or 1974, the witness responded:

During the war [with the Lon Nol soldiers], the Khmer Rouge did not have 100 millimeter big guns. We had that only from the Americans, after the war. There were only nine or 10 guns, artillery, at Kampot. This was after the war. The artillery unit was created after the war. We did not know how to operate that heavy artillery. Our skills were limited in fact.

As for what the situation was during the war in Kampot in 1973 and 1974, Mr. Raynor asked the witness who was in charge of the area. Mr. Rin replied that “in 1973 and ’74, many districts were controlled by the liberation army from Kep city, from the north of the cement factory. Kampong Trach, Touk Meas districts were controlled by the Khmer Rouge. There were no Lon Nol soldiers over there.”

Mr. Raynor asked if Mr. Rin ever remembered the liberation army attacking Kampot. Mr. Rin asked for an explanation of the question, to which the prosecutor responded that he was referring to a situation in which the liberation army took over Kampot from the Lon Nol soldiers. Mr. Rin said that he remembered that a battle on April 16 “was the decisive battle”; there were also “sporadic,” “small scale” battles, but he could not recollect them all.

Mr. Raynor explained that the witness had previously testified that between 1973 and 1975, he had been engaged in fighting all over Kampot. Therefore, the prosecutor wished to know whether between 1973 and 1974, the liberation army was in control of Kampot town. Mr. Rin denied this. Asked who was in control, Mr. Rin advised that it was controlled by “Lon Nol soldiers.” The prosecutor asked whether the liberation army was “happy about” this situation or whether they wanted the Lon Nol soldiers “out of Kampot.” Mr. Rin responded:

Of course, in war, we want to defeat our enemy. Of course, we were not happy. We had to send our forces to defeat our enemy. When you ask me when we are happy, of course, when we received the order to fight, we had to fight. This was a competition between one group and the other. … At the time, the Khmer Rouge never talked about negotiations to stop the fighting. They just focused on the fighting.

The prosecutor noted that according to Mr. Rin’s testimony earlier in the day, the liberation soldiers considered people in the cities to be enemies. In this respect, he asked the witness whether his superiors ever gave him orders concerning what he was to do with city dwellers in Kampot if he found them. Mr. Rin said, “At that time, my superiors told me we had to be careful not to target the civilians’ locations. We had to be careful. … My superiors have passed away already. They ordered us not to hit civilian targets. We did not target civilians. We were careful, in fact.”

This prompted Mr. Raynor to ask Mr. Rin whether the liberation army was using any mortars or shoulder-held rocket grenades, or whether it was possible that the CPK could have been shelling Kampot. Mr. Rin responded, “At that time, we only had 120 millimeter [artillery], 80 millimeter artillery, and B-40 rockets. We did not have many heavy weapons. It was not like the situation is now.” The prosecutor noted that the witness had confirmed that the Khmer Rouge soldiers had artillery, and asked if he was aware whether the Khmer Rouge soldiers had engaged in shelling Kampot between March and April 1974 and killing civilians. Mr. Rin denied this, stating:

Khmer Rouge soldiers at that time did not have many kinds of weapons, and we saved our ammunition. We did not waste our ammunition. This was very different from Lon Nol soldiers. Lon Nol soldiers could fire because they had assistance from Americans. We did not do that. … We fired only [if] we were certain that [a location] must be a military base. We did not have assistance from another. … So, the shelling or firing of hundreds of shells into the city was not true because we only had [low] numbers of artillery.

Mr. Raynor asked the witness whether he wished to say anything about approximately 8,000 people reported to have fled Kampot as refugees between March and April 1974. Mr. Rin declined, stating that this was beyond his knowledge as a “low-ranking soldier.” At this point, the president intervened, directing Mr. Raynor to move on since his question seemed to be “too slow” and “out of the scope of the case,” advising that the scope of the case is phases 1 and 2 of forced transfer and the history of the CPK. Mr. Rin knew only about military and communication structure, the president said, and Mr. Raynor should not ask irrelevant questions.

The prosecutor attempted to respond, stating that “every criminal charge has a context” before being cut off by President Nonn. The latter insisted that this was his ruling and the Chamber did not wish to hear questions that were “quite far” from the scope of the case.

A Meeting with Ta Mok and the Evacuation of Kampot in April 1975

Duly moving on, Mr. Raynor referred the witness to another statement he had made before the OCIJ, in which Mr. Rin had said:

The army convened a meeting to talk about how to topple Lon Nol’s regime and the plan to evacuate people. The meeting about the evacuation was held about one month prior to the fall of Phnom Penh. The order was given to force all people to leave all the cities and towns. This meeting was held in Phnom Sar, where Kampot’s military command headquarters was located. Sek, the chief of staff, chaired the meeting. Ta Mok, who was also present at the meeting, said, “It is not necessary to have markets or cities. All people must be evacuated to the rural areas in order to build the rural economy.” Ta Mok did not say who had made the decision on this matter, but the evacuation of the people from the cities was made for the entire country and was to take only two days.[33]

Mr. Raynor asked the witness whether this was correct. At this juncture, Mr. Koppe objected, arguing that the prosecutor was, in his view, leading the witness. Mr. Raynor asserted that this question was in context of Mr. Rin having answered questions all afternoon, in contrast to his attitude during the morning. The president responded to Mr. Koppe that quoting a previous statement from the same witness was not regarded as a leading question, a matter that had been addressed “many times already.”

Turning to Mr. Rin, Mr. Raynor asked him to estimate how many people were at this meeting attended by Ta Mok. Mr. Rin said that he was unable to do so. Mr. Raynor then asked if the witness knew when the plan to evacuate people had been decided upon. Mr. Rin replied, “After the army got into the city, all the people were told to leave. That was on April 16. Soldiers told the people to leave the city. The city was quiet. No one was over there.”

The prosecutor sought further clarification on Ta Mok’s instructions that all people were to move to the rural areas, asking whether or not this was the first time Mr. Rin had heard Ta Mok say something like this. The witness confirmed that this was the first time, adding that “[b]efore the end of the war, currency was printed, and then the currency disappeared. And then, after the war, of course there were no markets, there were no cities. This was like what [Ta Mok] said.”

Mr. Raynor also asked whether Ta Mok had said anything about the plan for the evacuation of the rest of the country. Mr. Rin denied this, explaining that Ta Mok “talked only about Kampot province, but of course, that practice was carried out throughout the country, and of course, that practice was the agreement of the leaders.” For the avoidance of any doubt, Mr. Raynor again asked Mr. Rin whether he had attended any previous meetings in which the evacuation of cities or towns was discussed. Mr. Rin denied this. Mr. Raynor then asked Mr. Rin what orders were given as to how the soldiers were to evacuate Kampot. The witness replied, “We ordered the people to leave the city, and that’s all. That was the order.”

At this point, a tumultuous storm began to pelt the ECCC courthouse. Meanwhile, Mr. Raynor asked Mr. Rin to explain what happened to the city dwellers in Kampot on the day of the evacuation. Mr. Rin responded, “Soldiers requested them to leave, and they arranged their belongings, and then they went away along the roads, and the town was quiet. They left the city.” Mr. Raynor followed up by asking whether the soldiers were armed. Mr. Rin denied this, explaining, “After the evacuation of the people, the soldiers were not over there. That was the responsibility of the others, as I have told you already. After the evacuation, others were responsible for the work over there. It was not the responsibility of the soldiers or the army anymore.”

Mr. Raynor explained that his questioned concerned whether, on the day of the evacuation, soldiers were armed or not. Mr. Rin said, “These soldiers did not mingle [among] the population and they had nothing to engage in the business of civilians, at least to the best of my recollection.” Mr. Raynor asked whether Mr. Rin was instructed as to what to do if civilians refused to leave Kampot. The witness denied this and explained he was only instructed that “everyone had to leave the city, and no one opposed this. Soldiers had to [remain stationed] at their respective units or sections.” Persisting on this theme, the prosecutor queried what arrangements had been made for the evacuees. Mr. Rin explained:

[This] was not [within] the competence of the soldiers. It was the sole responsibility of those who were in charge of the management of the civilian population, and it had nothing to do with the soldiers. We soldiers had to move to our respective units to do some farming, to make sure that we would be self-sufficient. I do not know much about what happened at the rear, because we were fully engaged in the front battlefield instead.

As for what happened to Lon Nol soldiers who were captured in Kampot at this time, Mr. Rin responded that “immediately after the war was over, we found it difficult to identify who was who, because everyone was already disarmed and had surrendered their weapons and we couldn’t say exactly who was a [Lon Nol] soldier.”

At this point, Mr. Raynor addressed the president, noting that it was 4 p.m., which is the usual time for the daily adjournment, and explaining that he had only approximately 10 minutes of further questions. He asked the president whether he might proceed or not. The president explained that it was indeed time for the daily adjournment. Further, he continued, as Mr. Raynor had used all of his time, including on a number of irrelevant questions, he would be required to utilize some of the Lead Co-Lawyers’ allotted questioning time on Tuesday, April 23 to conclude his questioning.

Hearings in the ECCC will resume on Tuesday, April 23, 2013, at 9 a.m. with the continued questioning of witness Chhouk Rin.