Former Warehouse Official Provides Limited Insight on Accused Persons’ Knowledge of Arrests, Rice Distribution

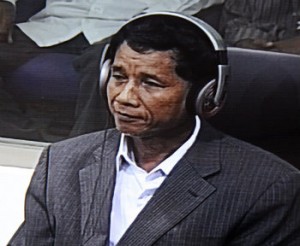

Former Khmer Rouge state warehouse official Ros Suoy took the stand at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Thursday, April 25, 2013. Much of Mr. Suoy’s testimony concerned the extent of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan’s knowledge of the arrest of senior Khmer Rouge leaders including Koy Thuon and So Phim. Focusing on a study session in which it was alleged that Koy Thuon’s taped S-21 confession was played aloud. Mr. Suoy, whom the Khieu Samphan Defense Team had requested as a witness, testified that Mr. Samphan did not play that tape, but Mr. Chea did, although by the time the tape was played, Koy Thuon’s status as a traitor was already well known.

Former Khmer Rouge state warehouse official Ros Suoy took the stand at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on Thursday, April 25, 2013. Much of Mr. Suoy’s testimony concerned the extent of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan’s knowledge of the arrest of senior Khmer Rouge leaders including Koy Thuon and So Phim. Focusing on a study session in which it was alleged that Koy Thuon’s taped S-21 confession was played aloud. Mr. Suoy, whom the Khieu Samphan Defense Team had requested as a witness, testified that Mr. Samphan did not play that tape, but Mr. Chea did, although by the time the tape was played, Koy Thuon’s status as a traitor was already well known.

Mr. Suoy also provided some insight into Khmer Rouge arrangements with respect to its stores of various goods. In particular, he acknowledged that during the DK period, the Khmer Rouge exported significant volumes of rice overseas.

Discussion of Time Allocation and Initial Details about the Witness

The hearing opened with Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn advising that today’s witness would be questioned first by the Khieu Samphan Defense Team as they had requested the witness. The defense would have a half day for questioning, and the Office of the Co-Prosecutors (OCP) and civil party lawyers would have the other half day. Trial Chamber Greffier Se Kolvuthy confirmed that all parties were present, with accused person Nuon Chea participating from his holding cell. Nearly 300 teacher’s college students dressed in colorful uniforms watched on from the public gallery, together with some villagers. All were from Kampong Thom province.

International Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Anta Guissé took the floor to inform the court that the Nuon Chea Defense Team would require no more than 30 minutes to question the witness, and her team intended to complete questioning by 11:30 a.m. President Nonn expressed his confusion, advising that today’s time allocation was different to that of the April 24 hearing.[2] Ms. Guissé explained that after her team finished at 11.30 a.m. the OCP should commence its questioning, with the Nuon Chea Defense Team having 30 minutes of questioning time at the end of the day. International Co-Counsel for Nuon Chea Victor Koppe, invited by the president to give comments, said that he had nothing to add, and that the proposed arrangement was identical to that in place in the April 24 hearing.

The witness Ros Suoy took the stand and began his testimony under questioning from the president, who sought the witness’s biographical details. Pressing his palms together in a sign of respect towards the president, Mr. Suoy advised that he is 60 year old, lives in Kandal province where he works as a rice farmer, and is married with six children.

Witness’s Interviews with OCIJ and the Documentation Center of Cambodia

The president asked Mr. Suoy if he had been interviewed by investigators of the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (OCIJ). Mr. Suoy confirmed that he gave an interview to people in 2002 and 2008. He also confirmed that he had reviewed the written records of his OCIJ interviews, and they were consistent with the accounts he had provided to the investigators.

Ms. Guissé asked Mr. Suoy to clarify details of the OCIJ interviews, noting that in the case file, there was only one interview with the OCIJ, but there were two other interviews with the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam). She asked if he could recall being interviewed by DC-Cam. Mr. Suoy confirmed that he “gave interviews to both the [DC-Cam] researchers and the [OCIJ] investigators” and that he was not interviewed by both entities at the same time. Ms. Guissé advised that the written record of OCIJ interview was dated March 14, 2008. She asked whether this was an accurate reflection of the actual interview date. Mr. Suoy confirmed this.

The witness said that the DC-Cam interviews took place before the interview with the OCIJ and that there were two separate interviews with DC-Cam. The first took place with only a Cambodian researcher who was conducting research on survivors of the Khmer Rouge regime. Mr. Suoy could not recall the second group of interviewers since “as a rice farmer,” he did not think he would ever have been called to the ECCC testify. This prompted Ms. Guissé to ask Mr. Suoy if the name “Steve Heder” meant anything to him. By way of denial, Mr. Suoy again emphasized that as a rice farmer, he was occupied with farming. Moving on, Ms. Guissé asked Mr. Suoy if he could recall if the interviews were recorded. Mr. Suoy confirmed this.

Further Biographical Details of the Witness

Next, Ms. Guissé asked if Mr. Suoy went to school. The witness agreed that he had and that “by the early 1970s, I was in grade seven. I could read and write.” Mr. Suoy explained, “I joined the revolution, the resistance movement, in late 1970. I would then go back and forth visiting my home. On April 15, 1973, I joined the Khmer Rouge movement.”

Asked to clarify what the resistance movement was, Mr. Suoy said, “I had joined the Vietnamese troops because the Vietnamese at that time joined forces to liberate Cambodia.” Ms. Guissé asked him to explain what prompted him to switch to the Khmer Rouge in 1973. Mr. Suoy said, “First I thought only Khmer people would be the best people to find peace from us. I learned that the Vietnamese people would eventually withdraw, leaving behind the Cambodian people helpless. So I decided that joining the Khmer Rouge would be [the best option].”

Mr. Suoy denied that there were any other reasons for him joining the Khmer Rouge. This prompted Ms. Guissé to request to read Mr. Suoy an extract from his August 19, 2003 record of interview with DC-Cam.[3] However, Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne intervened and said that this document was an annex to the introductory submission. He asked the defense counsel whether she had requested the use of this document in the Khieu Samphan Defense Team’s list of documents put before the Chamber. Ms. Guissé said that the document was a prior statement of the witness, and had been put on the Court’s interface in time. Pressed again on whether the document was on the list of documents, Ms. Guissé confessed that she did not know.

The Trial Chamber opened the floor to comments from the parties. International Senior Assistant Co-Prosecutor Tarik Abdulhak said that the document was on the interface and had also been put forward in an OCP document list, although it appeared not to have been on defense team lists. International Lead Co-Lawyer for the civil parties Elisabeth Simonneau Fort added that if the document was on any list, there should be no problem. However, she asked that this rule also apply to all decisions of the Chamber. Ms. Guissé confirmed that the document was indeed on the OCP document list and was duly permitted by the bench to proceed.

Ms. Guissé began to read to the witness an extract from Mr. Suoy’s DC-Cam interview. Mid-way, however, the defense counsel requested to put the document on screen so that Mr. Suoy could see it. The president said she would only be able to do so if she first asked the witness if he had seen the document before; if not, it would need to be withdrawn. Ms. Guissé explained that she had only been trying to expedite matters but would make do with reading the interview. Turning back to the witness and noting that the relevant DC-Cam interview was recorded, she asked whether Mr. Suoy had ever seen the transcript of the recording. Mr. Suoy said that he could not remember because, once again, “I focused only on … earning my living.”

Ms. Guissé then read the extract, in which Mr. Suoy had explained why he left the Vietnamese army. Mr. Suoy had said to DC-Cam, “I joined the Vietnamese military fighting along the Bassac river front. But after they mistreated me badly, I decided to defect from their unit.” Asked about the truth of this statement, Mr. Suoy agreed that he had indeed been mistreated.

Ms. Guissé asked Mr. Suoy to explain his role in the Khmer Rouge between 1973 and 1975. Mr. Suoy responded:

After I left the Vietnamese army, I looked for the Khmer army. At that time, I did not have a clear destination. I did not know where to go. Then I went to Svay Chek village, and I met a unit over there. I joined that unit. My first objective was to become a combatant. After I stayed there for a long time, I was assigned to be in the economic section, and I became a chief. This is what happened from 1973 to 1975. … I was a group chief. … The number of my subordinates was irregular. Sometimes there were up to 50 members. Those members came from defrocked monks, for example. Those forces were sent to my unit. They were educated. But of course, they were not forced. After they were trained, they were sent to the battlefield, so the number of forces in my unit was not stable, in fact.

In the economic section, Mr. Suoy “was not overall in charge of the whole unit. I was in charge of a small unit. I was in charge of food supply for the whole army. … I was responsible for collecting food, and the food would be sent to the frontlines, to the battlefields.”

Witness’s Role as Warehouse Supervisor Following the Fall of Phnom Penh

After the Khmer Rouge victory in April 1975, Mr. Suoy recalled:

My economics unit was allowed to go into Phnom Penh, and then a new unit was created. I became the chief of a 50-member unit. In my unit, at the beginning, there was an office called Office 311. My unit was assigned to stay at Kampong Teuk Kok warehouse, in front of Psar Thmei.[4] … My unit was in charge of a warehouse. At that time, there were two … companies. … Later on, another 50-member unit was created so that we could manage the list of … inventory in the warehouse. Later on, I became in charge of the warehouse. … I worked over there from 1975 until 1976, and then I was transferred to Kilometer 6. I was transferred over there in late 1976. … It was also a warehouse … a branch of the warehouse unit.

Asked how many warehouse branches existed, Mr. Suoy identified three: “a warehouse along the river … in front of Wat Phnom”; another at Chroy Changva; and another at Kilometer 6. He confirmed that he stayed at the Kilometer 6 warehouse until the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia in 1979. Ms. Guissé asked the witness if there was a warehouse at Kilometer 9. Mr. Suoy said he did not know and confirmed that he worked at only two warehouses between 1975 and 1979.

Moving on, Ms. Guissé asked Mr. Suoy if he knew what the Standing Committee of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) was. The witness denied this, explaining that “was the work of the upper level; I knew nothing about that.” He also knew nothing about the Central Committee and “knew only that Pol Pot was announced as the prime minister of the Democratic Kampuchea (DK).” Neither did Mr. Suoy know or hear about Offices K-1 or K-3. Mr. Suoy had heard of Office 870; however he did not know who headed that office or what its functions were. Mr. Suoy also denied working with S-21 security center or even knowing about it.

Ms. Guissé then asked if Mr. Suoy worked in the Commerce Committee between 1975 and 1979. Mr. Suoy denied this. However, with respect to the Industry Committee, Mr. Suoy said, “I used to transport products from a factory. Those products were stored in the warehouse. That’s all.”

Ms. Guissé asked if the witness knew a person named Sar Kim LeMouth.[5] Mr. Suoy denied this. He also advised that he did not work directly with Pol Pot and indeed never even spoke to him in person. Mr. Suoy confirmed that he had heard of someone named Pang but, again, “never met him in person” and did not know his role. The witness was also unaware of a person named Doeun. While people sometimes visited the warehouse, as Mr. Suoy had to fulfill his duties, he “did not rush to see who was coming to the warehouses.”

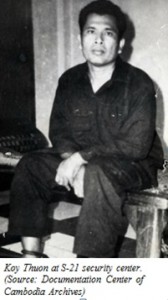

The witness’s direct supervisor was a person named Roeung. There were also other supervisors who the witness did not know. Mr. Suoy could confirm that he knew the name Teng, whom Mr. Suoy knew as Roeung’s deputy. As for whether he knew Vorn Vet, the witness said that he had heard of him but never met him and “did not have any work relation with him.” Mr. Suoy then confirmed that he knew a person named Van Rith very well and knew that he “was in charge of Commerce,” although he did not work directly with him. Mr. Suoy had also heard of Koy Thuon but again, “never met him in person.”

Focusing on Roeung, Ms. Guissé asked the witness if he knew the hierarchical structure of the warehouses was and who Roeung’s superiors were. Mr. Suoy said that he did not. Pressed to describe the governance structure of the warehouses, he said, “I only knew that when commodities or goods had to be distributed to sectors … documents had to be sent from K-25 requesting that goods be sent to various locations. These were the letters sent from that office. I don’t know who was overall in charge of the warehouses or above [them].”

Mr. Suoy himself received orders from Roeung. For example, after Roeung had received distribution orders, Mr. Suoy was to “load the goods up onto trucks before they could be distributed to various destinations.” Ms. Guissé asked Mr. Suoy whether he knew a person named Chuon. The witness confirmed this and explained that he “was the third person in the warehouse committee. This committee comprised of three people: Mr. Roeung was the head, [there was] another person and Mr. Chuon was a member in the committee.” He added that the third committee member was Teng. Next, the defense counsel asked if Mr. Suoy knew of Office K-7. Mr. Suoy denied this.

The witness advised that he “had no other duties other than those in the warehouses.” As for Mr. Suoy’s warehouse duties themselves, the witness explained:

I was tasked with the warehouse duties. At Kampong Teuk Kok, I was tasked with transporting materials to be stored at the warehouse. … I was instructed from superiors for the [storage] of rice. Some items could be requested and transported to the requesters, or stored at the warehouse. That was my main duty. By the end of the month, I had to file a report detailing the materials that had to be transferred to destinations. Roeung was the person I reported to.

As for what was actually stored in the warehouses, Mr. Suoy said, “At the warehouse at Kampong Teuk Kok, there were things, like materials transported from a foreign country, including hoes, fabric, steel, screws, etc. For the warehouse at Kilometer 6, there were materials transported or produce transported form the base, including rubber, resin, salt, rice, etc.”

Export of Rice and Rubber

Mr. Suoy then described the destination of the stored items as follows:

After these products or produce were stored in the warehouse, there would be requests for the products to be transported or distributed to other locations. For example, one particular zone might request some cement … pairs of shoes, garments. We had to entertain the requests through Mr. Roeung. Mr. Roeung would then render the request to his subordinates. I was one of them [who was] to ensure that these things would then be transferred to the requesters. …

I do not know how these requests could have been made. I only knew that documents were sent from K-25. I was instructed from Roeung to create the inventory … and I was [too] busy with the request to know what method of instruction could have been used from the zone.

Mr. Suoy did not know any foreign country sources of the items, explaining, “The only thing I knew was that whenever these materials were transported from abroad, we had to unload them from the train. I don’t know which country these items were sent from.” Asked about domestic sources of items, Mr. Suoy answered instead, “We exported only rubber and rice. These products would be transferred through train.”

Ms. Guissé asked whether the rice was exclusively for export or also for Cambodian consumption. Mr. Suoy explained, “This rice was transported from sectors and zones … and we had to transport the rice for the state.” He continued, “I don’t know whether the rice was destined for local consumption or not, but I knew that rubber and rice were requested for export to foreign countries. I don’t know what the destination countries were because when the request was received, we would employ some porters to load the rice onto a freight train.

Asked if he ever personally prepared rice to be shipped to the zones, Mr. Suoy said, Rice was not supposed to be redistributed to the zones or the sectors, but the other way around. We had to transport the rice only to the warehouses before they would be distributed to a foreign country.” At this point, Ms. Guissé read to the witness an extract from his interview with DC-Cam, in which he had said that less rice was exported to foreign countries than was distributed. [6] Asked if this refreshed his memory, Mr. Suoy stated:

When I gave my interview to the researcher, perhaps my message was not properly received. Today I am telling the truth. He may have missed my message because at that time, when I said that less was exported, I was referring to the rice that was distributed for the local consumption. … Indeed, un-husked rice was not exported in large amounts. Un-husked rice would be used for local consumption. Husked rice would be exported in great amounts. … No milled rice was ever distributed in Cambodia. It was destined for export. However, when time passed, rice production decreased. That’s why exports also decreased.

Mr. Suoy confirmed that this meant that when rice production dropped, exports also dropped.

Witness’s Knowledge of Khieu Samphan and Other Leaders

Moving on, defense counsel asked Mr. Suoy if he knew Mr. Samphan and his roles. Mr. Suoy responded:

I knew him, but of course, I was not close to him. I just saw him only. … From 1970 to 1973 and 1975, I never saw him. However, after Samdech[7] appealed to the people to rise up, to struggle, to liberate the nation, then I only knew that Hu Yun, Hu Nim, and Khieu Samphan were the leaders of the movement. Later on, from 1975 until the announcement of the prime minister, then I realized that Khieu Samphan was not a top leader or a senior leader. …

Civilians or soldiers believed that [those] three [leaders] were the big leaders or the top leaders, however, when the prime minister was announced, we all realized that he was not a top leader at all. … I knew about that not because I attended any meeting or discussion with the senior leaders but in each unit we met with our colleagues, we discussed with each other, and then we knew that [Mr. Samphan] was not … a top leader. But I did not know clearly about his rank.

Ms. Guissé asked if Mr. Suoy saw Mr. Samphan between 1975 and 1979. Mr. Suoy confirmed that he saw Mr. Samphan but “could not remember the date. At that time, we did not know whether it was Monday, Saturday, Sunday. No. We only focused on our work, because we were afraid of making mistakes. … I saw him [only] when he called me to attend study sessions.”

At this point, Ms. Guissé asked if Mr. Suoy ever recalled Mr. Samphan coming to visit his warehouse. Mr. Suoy confirmed, “I used to see him visit the warehouse, but I did not get close to him. I just knew that he came to visit.” The president then adjourned the hearing for the mid-morning break.

Following the break, Ms. Guissé sought to again refresh Mr. Suoy’s memory, this time concerning his knowledge of the person named Doeun. She noted that in his second DC-Cam interview, Mr. Suoy had said, in answer to a question about who was in charge of Office K-7, “I only know that Pang was the chief. He was an office chief. Another one was Doeun, about whom I was confused. Doeun often came to inspect the warehouse, so my conclusion was that Doeun was in charge of the warehouse.”[8] Ms. Guissé asked whether this refreshed Mr. Suoy’s memory about Doeun’s frequent warehouse visits. The witness said his memory was not clear at the time, and that “I never met the person who came to do the inspection. Only upon their leaving the premises did I hear from colleagues who came to inspect the warehouse.” He continued, “When it comes to Pang being the head of the office, this was part of my speculation or conclusion because I could feel that someone who had nothing to do with the warehouse would not come to the warehouse.”

Mr. Suoy then confirmed that he never saw Pang or Doeun. He added that “senior people came to the warehouse,” but he did not know their names.

In the same DC-Cam interview, Ms. Guissé continued, the witness had testified that Mr. Samphan was “startled” that cadre members did not have enough to eat and only ate gruel.[9] The defense counsel asked how he knew this and what the circumstances of the conversation were. Mr. Suoy explained:

It happened when subordinates of the warehouse had to be called to attend sessions where [Mr. Samphan] would chair and explain how we could properly keep materials in the warehouses. After the sessions, we could convene sessions for discussions. But we just speculated, concluded that Mr. Samphan … would be surprised to learn that other groups would not have enough to eat. We in these private conversations believed that Mr. Samphan could have been surprised.

To refresh Mr. Suoy’s memory on this matter, Ms. Guissé noted that in his answer to Steve Heder during the second DC-Cam interview, Mr. Suoy had said that “rice was shared among us … of this paper size … but there was no food ration. We never ate gruel.”[10] The defense counsel asked how, if the witness never ate gruel, Mr. Samphan could have been startled by that. Mr. Abdulhak objected, however, that this question was “entirely speculative” and inappropriate. Ms. Guissé rephrased the question, asking if this refreshed Mr. Suoy’s memory about the food he ate. Mr. Suoy agreed that it did, and he had eaten rice, but “normally, there was nothing but gruel.”

Ms. Guissé then turned to a portion of Mr. Suoy’s DC-Cam interview in which the witness said Mr. Samphan had accessory duties that were “social in nature,” did not do “vital work,” and did not “live in luxury” or “swank around” like the others.[11] Ms. Guissé asked whether Mr. Suoy stood by this. Mr. Abdulhak objected that these were several assertions “lumped into one,” and the questions should be separated out so that there could be specific responses to each question. Ms. Guissé said she simply quoted the witness’s entire answer to a question DC-Cam asked. Ms. Guissé then asked Mr. Suoy if this was a good description of what he saw of Mr. Samphan when he visited. Mr. Suoy agreed that it was.

As for the subject of the education sessions with Mr. Samphan, Mr. Suoy explained that he “did not understand the topics or the objectives of the study sessions, but I still recall some of the instructions he provided to us. He just asked us to manage the materials, to keep the materials in the warehouses properly, and how to maintain them.” Thus, Mr. Suoy confirmed, they were about “technical aspects” of the warehouse work. Concerning whether Mr. Samphan ever gave political teachings, Mr. Suoy denied this.

As for the subject of the education sessions with Mr. Samphan, Mr. Suoy explained that he “did not understand the topics or the objectives of the study sessions, but I still recall some of the instructions he provided to us. He just asked us to manage the materials, to keep the materials in the warehouses properly, and how to maintain them.” Thus, Mr. Suoy confirmed, they were about “technical aspects” of the warehouse work. Concerning whether Mr. Samphan ever gave political teachings, Mr. Suoy denied this.

Finally, Ms. Guissé turned to the topic of having heard Koy Thuon’s S-21 confession, which the witness then referred to having heard on tape. Mr. Suoy had testified to the OCIJ that while the tape was playing, Mr. Samphan was present.[12] Asked how many times Mr. Chea and Mr. Samphan played the confessions, the witness said that only Mr. Chea played the tape of the confession, and Mr. Samphan was not there.[13] Ms. Guissé asked Mr. Suoy to stipulate whether or not Mr. Samphan was present. Mr. Suoy said that it was perhaps a misunderstanding, “but I remember clearly that I said he was not present.”

Further Examination of Witness’s Knowledge of Khmer Rouge Offices

Ms. Guissé ceded the floor to her counterpart, National Co-Counsel for Khieu Samphan Kong Sam Onn. He first redirected the witness to the issue of Office K-25 and asked Mr. Suoy to explain what K-25 was. Mr. Suoy responded that he did not know “what this office was and who was in charge overall of it. I said this clearly. I knew only that requests were sent out from this office for items to be redistributed from the warehouses where I worked. I only knew the codes on the letter of requests.” Mr. Sam Onn asked where Mr. Suoy saw the “K-25” code. The witness said he could not recall, but that Roeung would pass distribution requests onto Mr. Suoy telling him that the request was from K-25.

Mr. Sam Onn asked if Mr. Suoy knew a person named Khiev Noeu. The witness denied this, prompting the defense counsel asked if Mr. Suoy ever received items from or redistributed items to the Southwest Zone. Mr. Suoy agreed that he had but that different people were sent from the southwest and therefore did not know “who was who.” The witness also denied any knowledge of a person named Sen. At this point, Mr. Sam Onn explained that Mr. Neou had testified to the Trial Chamber on June 21, 2012 that his nephew-in-law, Sen, Mr. Neou could contact Mr. Samphan and request some materials.[14] This witness had also testified that Sien, the nephew-in-law, was in charge of Office K-22.

The defense counsel asked if Mr. Suoy knew what K-22 was. The witness said he had heard of it but “never had any contact with the people there.” Asked whether he ever received redistribution requests from K-22, Mr. Suoy said he could not remember because “after the materials were transported out of the warehouses, I would never have good track of who could have been the requesters.” Thus, Mr. Suoy confirmed, he could not recall any requests from K-22.

Study Sessions with Khieu Samphan

Returning to the topic of study sessions with Mr. Samphan, Mr. Sam Onn asked whether Mr. Suoy could recall attending a study session with Mr. Samphan on January 5, 1979. Mr. Suoy confirmed this. He could not “recall exactly the time,” but it was in the morning. Regarding details of the session’s participants, Mr. Suoy said that he only “focused on people from the warehouse unit. I did not pay attention to the others. I do not remember the exact number, but of course, the leader of the battalion, company, and group chief attended the study session.” With respect to the contents of the session, Mr. Suoy relayed, “After the situation in Phnom Penh changed, [Mr. Samphan] called us so that he could give advice, inform us about the situation in Cambodia, and … that we had to leave Phnom Penh temporarily. … I just remember that he told us to leave Phnom Penh temporarily.”

Mr. Abdulhak took the floor for the prosecution, maintaining the focus on that meeting. He noted that, in responses to DC-Cam, Mr. Suoy had said that Mr. Samphan led the meeting and that other attendees included “leaders from the army, industry, commerce, and state warehouses.”[15] The prosecutor asked whether this statement was true. Mr. Suoy confirmed it but qualified, “I did not know them, but of course, people from different ministries and offices attended that session.” As to their levels within the hierarchy, Mr. Suoy said that “I saw only their uniforms, but I did not know about their ranks.”

The prosecutor asked how Mr. Samphan called people to that meeting. Mr. Suoy explained, “This does not mean that he called us directly. He may have told Mr. Roeung. Mr. Roeung told us to go over there to that meeting.” Mr. Abdulhak queried whether this was the usual procedure. Mr. Suoy answered instead, “At that time, the situation in Cambodia had changed. At that time, he called us to attend that meeting because maybe he wanted to tell us about that change.”

Mr. Abdulhak then advised the witness that, when asked by DC-Cam whether Mr. Samphan had discussed the “enemy burrowing from within,” Mr. Suoy had said yes and that “based on his situation, the current situation might have been partly caused by some internal problem without which the outside enemy might not have been able to attack us.”[16] Mr. Abdulhak asked whether this statement was indeed accurate; Mr. Suoy agreed that it was.

Continuing to read from Mr. Suoy’s statement to DC-Cam, Mr. Abdulhak noted that the witness had described, “In the meeting, [Mr. Samphan] explained the situation of the Viet attack, the temporary retreat, and the future plan.”[17] Asked to comment on this, Mr. Suoy agreed that Mr. Samphan had discussed the Vietnamese attack and said that “we left the city temporarily only, and then we [would be able] to plan the [counter] attack against the Vietnamese.”

Mr. Abdulhak noted how, in his statement to DC-Cam, Mr. Suoy had said that Mr. Samphan was focused on teaching administration and Mr. Chea taught politics.[18] He said to DC-Cam that they were the same thing, but that “on the administration side, they talked about how to organize the village structure and how to guard and protect it.” Mr. Abdulhak asked if this statement was correct. Mr. Suoy agreed that it was.

As to whether politics or administration were the same thing or interrelated, Mr. Suoy stated, “From my own analysis, the administration and politics could not be the same. Politics did not focus on the arrangement or organization, they just made the decision. Administration … just implemented the decision. But politics was about setting the policy.” Mr. Suoy confirmed, when asked, that politics was about “setting policies” while administration was about “implementation.”

Nuon Chea’s Role in Study Session and Witness’s Knowledge of Traitors’ Fates

Mr. Abdulhak asked whether, in the study sessions with Mr. Chea, the latter ever taught the witness about internal enemies or traitors. Mr. Suoy explained, “He taught us about politics. He taught us about the future goals.” He continued, “I cannot remember the confession made by Koy Thuon played by him, but of course he used to describe, mention traitors, but I do not remember about the traitors in detail, and I did not pay attention to that issue at all.”

Mr. Abdulhak then relayed to the witness how he had testified to the OCIJ about hearing Mr. Chea say that both So Phim and Koy Thuon were traitors.[19] The witness confirmed that this was an accurate statement. As to how traitors were to be dealt with, Mr. Suoy said Mr. Chea “advised us [at that time] to conduct the investigations within our units to search for more traitors.” However, Mr. Suoy could not remember the exact date of Mr. Chea’s comments in this regard.

The prosecutor highlighted how Mr. Suoy testified to the OCIJ that his colleagues told him Pang had been arrested for betraying Pol Pot. Mr. Abdulhak asked the witness to describe the circumstances of this conversation. Mr. Suoy explained that after he returned from the study session, he had a conversation with his friends in his unit: “[We] would talk to each other; we would discuss. They talked about the disappearance of this person, that person. Of course, we did not know why they disappeared. We just knew that they disappeared.”

Following the lunch break, Mr. Abdulhak read the following extracts from the witness’s interview with DC-Cam in which he discussed traitors, and particularly, finding out that So Phim was a traitor:

I knew about it when I was called to study politics. There, they spoke about who were the traitors, which strings and persons were arrested, and in order to suppress it, we must keep an eye on the hiding elements and strings that had infiltrated within us.

I knew from them in the study session. For example, they told us that although we had arrested some of them in the string, its network still existed. They told us that they were monitoring the situation constantly. They published that information in a document, like theFive Flags journal.[20]

Mr. Abdulhak then asked Mr. Suoy a series of questions eliciting details of these study sessions. Mr. Suoy explained:

After the study sessions, I heard that So Phim was a traitor. That was told to us by Mr. Nuon Chea during the study sessions. Regarding the monitoring of the network of traitors, this matter was also raised during the sessions. Nonetheless, I had no interest in following up what could have become of those people. …

The sessions were conducted sometimes at Onalom Pagoda, Borey Keila, or the Olympic Stadium. … Nuon Chea was lecturing the sessions; however there were other people who started the introduction and the formalities of the sessions before he took the floor. …

I do not know the senior leaders. There could have been some of them in the sessions, but I just do not know them. … The sessions were not on a regular basis [or in the same place]. … They were not occurring at the same time [as the sessions taught by Khieu Samphan].

The Operation of State Warehouses

Next, the prosecutor sought to find out more about the operation of the state warehouses. Mr. Abdulhak began with the situation of exports, noting Mr. Suoy had testified to DC-Cam:

Each time, over 60 to 100 tons of rice was sent out [to] Canada and Hong Kong. I knew that because on the stamped seal receipt, it said that this much rice had to be transported to Kampong Som. …

The machine in the rice mill at Kilometer 6 could be used to adjust rice quality automatically. The grains flew into the sacks which were set up in line. When one sack was full and reaching the weight of 101 kilograms, the machine automatically dropped it on the ground and then picked and filled up the next sack. The weight of the rice grains itself was only 100 kilograms and the weight of the sack was one kilogram. That machine could pack 1,600 to 1,700 sacks of rice per day.

If we operated only one rice mill we would not be able to meet their demand. … That is why all four to five rice mills had to operate constantly. [21]

Mr. Suoy confirmed that all of these statements were correct. Mr. Abdulhak asked the witness also to confirm that, as he testified to DC-Cam, “every ministry” in Phnom Penh came to the Kilometer 6 warehouse to get rice. Mr. Suoy agreed that this was so. My. Abdulhak asked whether disbursements always had to be approved by K-25. Mr. Suoy agreed that “only K-25 would [issue] such requests for rice to be distributed.” Mr. Suoy then confirmed that rice was never disbursed to the zone.

Moving on to visits by Doeun, Mr. Abdulhak noted that in his testimony to DC-Cam, Mr. Suoy had described Doeun as “the big shot,” and how each time Doeun visited the warehouse, the witness would need to meet him and discuss the things stored in the warehouse.[22] Mr. Abdulhak asked if this was accurate. Mr. Suoy said that he did not remember “who would come to do the inspection at the warehouses [and] knew about this only after the persons went back.” However, Mr. Abdulhak insisted on this point, asking Mr. Suoy to confirm if he ever spoke to Doeun about such matters. This prompted Mr. Suoy to say that he did, that he did not recall everything, but that this “rang a bell.” Mr. Suoy said that “Doeun was a handicap … and he came to the place.” The prosecutor noted that Mr. Suoy did indeed testify about Doeun’s limp to OCIJ.

Mr. Abdulhak turned to the subject of Mr. Samphan’s visit to the warehouse, inquiring as to who accompanied Mr. Samphan on the visit. Mr. Suoy responded that he could not recall but that when Mr. Samphan came, he “did not have a modern vehicle to ride to work. He was seen coming to work in a pair of flip-flops with a Lambretta [vehicle].” Mr. Abdulhak asked if Mr. Chea and Mr. Samphan ever visited the warehouse together. Mr. Suoy denied seeing this; he also added that Mr. Samphan did not visit frequently. On the subject of Doeun’s fate, Mr. Suoy said that he did not know what happened to him.

Turning to the authority structure of state warehouses, Mr. Abdulhak noted Mr. Suoy had testified today that Roeung was in charge of the warehouses. He contrasted this with the statement Mr. Suoy gave to DC-Cam that the “general chairperson was Rith,”[23] “one section [leader] was Teng,” and that “at Chroy Changva and Russey Keo, [the leader] was Chuon.”[24] Mr. Abdulhak asked whether Rith and Roeung could possibly be the same person. Mr. Suoy agreed and explained that Roeung was originally known as Rith, but as this was the same name as Van Rith, he decided to change his name to Roeung.

This prompted the prosecutor to focus on the relationships of the warehouse leaders to Rith. In particular, Mr. Abdulhak noted that in answer to a question from DC-Cam, Mr. Suoy had said that the Rith in charge of the warehouse was “smaller” than the Rith who was the chairman of Commerce.[25] Mr. Abdulhak asked whether this meant that Rith alias Roeung was subordinate to Van Rith. Mr. Suoy answered instead, “After we came into Phnom Penh, Roeung was separated from Van Rith because Roeung was in charge of the state warehouse and [Van Rith] was in charge of Commerce.” Mr. Abdulhak asked the question another way, by drawing Mr. Suoy’s attention to another statement he made to DC-Cam that the state warehouses were smaller than Commerce and lower in rank.[26] Mr. Abdulhak asked Mr. Suoy if this accorded with his understanding. Mr. Suoy agreed that this was so.

Arrests and Associated Instructions: “No One Could Know When Their Time Would Come”

Mr. Abdulhak shifted focus to arrests and their associated instructions and asked Mr. Suoy if there were disappearances from the warehouses where he worked. The witness responded:

Yes of course there were … but I did not see any torture. At that time, people were called to attend meetings, for example, and then they were told that they would be sent to a new location. This is what I saw. Regarding those who were arrested, some of them came back, and some of them disappeared, and I did not know how they disappeared.

This prompted the prosecutor to advise Mr. Suoy that in one of his DC-Cam interviews, he had said:

No one could know when their turn would come. Everyone was worrying for him or herself and doing whatever he or she could to avoid any mistake. … During that time, after any persons had been arrested, I thought they were taken to build the road. That was what I knew. But if any person was implicated by multiple, previously arrested persons, that person was treated as a traitor and subsequently killed.[27]

Mr. Suoy agreed that this was true and that “[t]hese people would be invited to a meeting, and they were told that they would be sent to a new location, and then they disappeared. This is what I saw.” Mr. Abdulhak asked the witness whether he was ever required to hand over a person who was to be arrested. By way of denial, Mr. Suoy said that arrest plans were kept secret. This prompted Mr. Abdulhak to read another passage to him:

If they wanted to arrest any person, they would come or call me on the phone, telling me that they wanted this or that comrade to work with them. I then called that person from his work to meet with them.[28]

Whenever the national security unit came to arrest any people, they already had the names of the targeted person in their hand. Before they came, they telephoned us telling us that they wanted to come to work with us at a certain time and a certain hour.[29]

Mr. Abdulhak asked if this was an accurate account. However, Mr. Koppe objected, asking if the prosecutor could explain how this line of questioning was relevant to the present trial. Mr. Abdulhak replied that this objection had been raised many times and “could not be taken seriously” as this evidence went to the functioning of key CPK ministries and offices. This prompted the Trial Chamber judges to briefly convene, after which President Nonn overruled Mr. Koppe’s objection and directed Mr. Suoy to respond to it. Mr. Suoy confirmed that the passages were correct.

The prosecutor then read another passage to the witness from his DC-Cam testimony. In this passage, Mr. Suoy had said, “When they called someone to a meeting like that, it meant that they arrested him or her. Whenever the persons were called from their workplace to a meeting, they were terrified. They knew that they were being arrested but not sure if they would be definitely killed.”

Mr. Abdulhak asked if this “climate of fear” did indeed exist. Again, this elicited an objection from Mr. Koppe, who said that he did not know how the “climate of fear” related to communication and structure. Mr. Abdulhak agreed to indulge Mr. Koppe on this occasion, and move on, although he noted his view that his question had been appropriate.

Next, Mr. Abdulhak reminded Mr. Suoy that he testified to DC-Cam that people could not disobey arrest orders from national security.[30] He asked Mr. Suoy whether his understanding was therefore that the national security forces were working on “upper echelon” orders. Mr. Suoy agreed with this. However, he did not address a question from Mr. Abdulhak as to who the “upper echelon” was, stating instead, “Roeung called me through mobile phone or fixed phone to call his person or that person to a meeting. … I do not know whether that person was arrested or not, but I noticed that when that person was called to a meeting, that person disappeared.”

Playing of Taped Koy Thuon Confession at a Study Session

Moving on, Mr. Abdulhak directed Mr. Suoy to his testimony to the OCIJ that that he had attended a study session at which a tape of Koy Thuon’s confession was played and that Khieu Samphan was not at this study session. However, Mr. Suoy had testified to DC-Cam on the contrary that “they had the document and audio cassette about Koy Thuon. When Khieu Samphan called me to a study session, he played the cassette of Koy Thuon’s confession for me to listen to.”[31] Mr. Sam Onn objected to this, arguing that when the DC-Cam document was read in Khmer, it did not indicate that Mr. Samphan played the tape.

Mr. Abdulhak said that he was reading the Court’s official translation and could proceed in the manner that the Court preferred. The president advised Mr. Abdulhak that the document had been produced by DC-Cam and the witness had not seen it before but permitted Mr. Abdulhak to extract some content from the document to put to the witness. The prosecutor proposed that his national colleague read the document directly from the Khmer, which the president permitted. National Senior Assistant Co-Prosecutor Veng Huot then read the passage as follows:

With regard to Koy Thuon, there was a tape recording that was played during a study session when Mr. Khieu Samphan was present. … The confession was played to the participants. … I do not remember the details [of the confession], but I remember that there were several attempts to topple Pol Pot but they were not successful.

Mr. Sam Onn asserted that in the text, it said that the tape was played but did not stipulate that Mr. Samphan had played it. President Nonn agreed that the argument was “plausible” and that in Khmer, the document said that the tape was played in passive form without stipulating exactly that Mr. Samphan had played it. Mr. Abdulhak agreed to proceed on this basis, then, and asked Mr. Suoy first if the confession tape was played in a session attended by Mr. Samphan. Mr. Suoy responded, “I recall having said it like this: I said that the tape recording was played. It was Nuon Chea who played the tape.” Mr. Abdulhak pressed Mr. Suoy on whether it was nevertheless correct that Mr. Samphan was present. Mr. Suoy said, “I think perhaps there was a kind of miscommunication already in that interview. I didn’t say that Khieu Samphan was present in the session when the tape was played. I think that the interviewers could have [been] mistaken.”

Mr. Abdulhak explained, however, in another part of Mr. Suoy’s interview with DC-Cam, he had testified that “it was either Khieu Samphan or Nuon Chea” who had played the confession tape at the study session.[32] The prosecutor asked if Mr. Suoy had made this statement. Mr. Suoy agreed that he had, but explained that since the interview, “I remember this vivid memory that it was Nuon Chea who played the tape, not Khieu Samphan.”

Finally, Mr. Abdulhak referred the witness to his testimony that he did not think Mr. Samphan was a top leader. He asked whether Mr. Suoy was aware that Mr. Samphan had made a statement to the ECCC confirming he had been a member of the Central Committee. Mr. Suoy responded:

Whether [Mr. Samphan] belonged to the Standing Committee or the Central Committee is not [within] my knowledge. … I knew that he was the president of the State Presidium. Nonetheless, whatever decision was made could have been rendered by the Party.

I am not really here to act in favor of him, but the truth is that whenever he was called to a meeting, we could never hear him say anything other than asking us to properly manage the materials in the warehouses. It was more about maintaining the materials.

Mr. Abdulhak concluded his questioning at this point. This prompted Ms. Guissé to rise and say that the way Mr. Abdulhak had put his questions, there was a suggestion that the defense counsel had quoted another witness this morning and wanted to make clear that she had not. Mr. Abdulhak explained that he had been referring to a statement from which Mr. Sam Onn, not Ms. Guissé, had read.

Clarifications Requested by the Civil Party Lawyers

Following the mid-afternoon break, Ms. Simonneau Fort took the floor to begin questioning on the part of the civil party lawyers. She first noted that Mr. Suoy had testified that defrocked monks who were reeducated were part of his unit in 1973. She asked who reeducated the monks. Mr. Suoy explained:

The defrocked monks were conscripted, and when people were gathered from villages and communes and recruited, they were sent to my location. This location was not an educational center. It was more like a temporary transit area. People would have to stay there for a short while before they could be transferred to other places. People who were there, I don’t know if they were there on their own volition or they were forced to move there, but some of them were defrocked monks.

Turning to the topic of the warehouse, Ms. Simonneau Fort asked whether there were loudspeakers at Mr. Suoy’s warehouse canteen or rest area. The witness replied, “At the cooperatives, there were loudspeakers where songs could be heard.” He continued, “People at the cooperatives could hear these songs. They could also hear comments on the radio broadcast regarding how to rebuild the country, so on and so forth. This happened on a daily basis. … There were [also] loudspeakers installed permanently at the warehouse.”

Ms. Simonneau Fort also asked Mr. Suoy if documents and reports were stored somewhere in the warehouse. Mr. Suoy replied, “All documents, after January 7 [1979], including the keys to the warehouses, were left behind at the warehouses. We had to abandon them.” She then asked the witness if he was ever given documents such as confessions when internal security authorities came to arrest people at the warehouse. Mr. Suoy said, “I was not the chairperson. I was assigned some tasks, including the management of the materials. … When it comes to the documents relating to the arrests, I do not know and I never received such documents. The arrests were made at my place, but I never knew the offenses that these people could have been accused of.”

Ms. Simonneau Fort highlighted Mr. Suoy’s testimony that Nuon Chea had told him to undertake tasks to “unmask traitors,” asking whether Mr. Chea had characterized this as a “duty.” Mr. Suoy explained:

After the study sessions, we were asked to uncover the internal enemies, but the people who were the targets for arrest were people from the same village. I just didn’t know what happened to them that they had to be arrested. Some of them are still alive although some disappeared. The arrests were made after 1976, and combatants in my units, some of whom were arrested – altogether eight people had been arrested [from] the Kampong Teuk Kok warehouse alone. At the Kilometer 6 warehouse, a few people had been arrested as well. This included porters. Again, I did not know why they had to be arrested, but I knew that phone calls were made in which some people had been asked to go to particular meetings. After these meetings, I did not see those people. I never knew the offenses these people could have committed.

The civil party lawyer noted Mr. Suoy had previously testified to the OCIJ that his brother-in-law had been arrested.[33] Asked when this had occurred, Mr. Suoy responded that after being interviewed by DC-Cam, he was invited to the visitor center for legal training. He then saw a photo of his brother-in-law, and through DC-Cam research, “we found another sibling of mine, a sister.” He learned that “these people were executed at S-21” and had been provided the exact date of these arrests by DC-Cam. Ms. Simonneau Fort asked if Mr. Suoy’s brother-in-law was executed before or after 1975. Mr. Suoy said that it was in 1977.

Next, Ms. Simonneau Fort noted Mr. Suoy had testified to the OCIJ that poison had been put in his food and that he also saved some children from poisoned food as well.[34] Asked to elaborate on this, Mr. Suoy said:

After several people had been arrested and new people had to take over from the others in the positions, anger was instigated. At Kilometer 6, people were removed. When I was there, I could see that people started to take revenge. They did their best to show that they were bending and later on, research was conducted to find out who was behind this conduct. The people that did these things were arrested. Normally, food would be delivered to the leaders. I at the warehouse had to also eat the food they delivered to us.

The children, who had been very hungry for food, had to eat this food without knowing that the food was laced with poison. Knowing that these children were poisoned, I had to pick some coconuts. I used the coconut juice to counteract the poison. I was accused of picking the coconut, but later on, the children were transferred to the hospital and they were saved.

At this point, the president interrupted, advising Ms. Simonneau Fort to remember Mr. Suoy was not a civil party and that her questions should be limited to relevant subjects. Ms. Simonneau Fort responded, “If we are not concerned about the state of mind of people responsible for structures, whatever the level, then we will lose a good part of the explanation of things.” The civil party lawyer then moved to her final question, asking Mr. Suoy to confirm he was afraid and did not know when he would be arrested. Mr. Suoy agreed this was true and explained:

At that time, if we were found out to be connected to the people who had previously been arrested, including our superiors, then we had reason to be fearful, because families and subordinates of the people who had been arrested would have been the subject of further arrest. I was very fearful. I just realized that I had to hide my identity all along.

Witness’s Experiences of the Evacuation and Further Clarifications on Various Issues

Taking over for the civil parties, National Lead Co-Lawyer for the civil parties Pich Ang asked Mr. Suoy whether he saw Phnom Penh being evacuated. The witness confirmed that he saw “crowds of people on the streets leaving the city.” Mr. Suoy said that he saw the evacuees “in the countryside,” not Phnom Penh. Asked to be more specific about the location of that countryside, Mr. Suoy said that he was in Takeo province at the time. By the time [my unit] got to Phnom Penh, there were no people.”

Mr. Ang asked whether Mr. Suoy saw people marching in the opposite direction while his unit was traveling to Phnom Penh. Mr. Suoy said, “During the course of my journey, we first met at Sector 25 along the Tonle Bassac River. We were at the Kampong Teuk Kok warehouse to the east of Psar Thmei, and we did not see any evacuees.” He could not recall the exact date on which his unit was transferred.

Mr. Ang then asked the witness a series of questions seeking descriptions of the evacuees. Mr. Suoy said:

People would never be happy to leave their houses where they had been living for a very long time already. I could see people crying [constantly] and vehicles that had been broken midway and had to be pushed or pulled by family members. …

People [came] from all walks of life: the sick, people whose parents were very ill, who could not walk, people who had to take their cars which ran out of gasoline and they had to push their cars. People had to stop midway to exchange their clothes for some food.

The civil party lawyer asked if the Khmer Rouge provided care for newly arrived evacuees. Mr. Suoy responded, “In simple terms, no.” Mr. Ang asked what happened to people when they arrived at a new destination. Mr. Suoy recounted:

People were clearly classified. Those who were moving from Phnom Penh to the countryside were regarded as the “April 17” people. They were treated differently. … These people were trying to move to their hometowns or places where they had their relatives or loved ones. But even though they could manage to reunite with their family members, those people appeared to be very cautious sharing food with newcomers. Authorities at the base did not pay much attention to the wellbeing of new people.

Mr. Ang queried what would happen to someone known to assist the “new people.” Mr. Suoy responded, “The reason that the ‘base people’ were afraid was that people could not even talk amongst ourselves at the worksites. We could not be seen to be talking to one another even briefly because we would be arrested and executed.” He concluded, “The ‘April 17’ people were placed in an area where they could not mingle with the ‘base people.'”

As to why people would be afraid to be identified as “April 17” people, and who ordered the mistreatment of “April 17” people, Mr. Suoy said, “It was part of the business of the commune chiefs or people in the area, but it is commonly known that the ‘April 17’ people were classified and placed in different locations apart from the ‘base people,’ and treatment was also different.”

Moving on, Mr. Ang asked the witness to describe the connection between warehouses and other sections. The witness responded that he did not know, as he knew only about the warehouses where he worked.

The civil party lawyer asked Mr. Suoy who was above his superior Roeung. Mr. Suoy said that he knew only Roeung. As for who used to visit the warehouses, Mr. Suoy said this had been mentioned already and included Mr. Chea and Mr. Samphan, but the witness “knew some of them only.” Mr. Ang asked whether these leaders ever talked to him when they came to visit. Again, the witness denied ever meeting them but said that “they gave advice through other cadres and I knew that. He told us to take care of the equipment, to maintain the equipment, but I never met him in person.”[35] Asked to describe that advice, Mr. Suoy said that his superiors would convey this advice to him but did not, while doing so, mention either Mr. Chea or Mr. Samphan’s name.

At this point, the civil party lawyer asked the witness whether the materials from the factories were ever distributed to people. Mr. Suoy said that as far as he knew, it was distributed to people “once every week,” but he “did not know whether the material really reached the people.” He further explained that he “did not distribute the material directly to the people at all.” He “inspected the invoices and then took the material onto the truck and then … signed. … That’s all.” Pressed for further detail, Mr. Suoy said that from the warehouses, “the state had to distribute the material back to the zones and sectors.”

Nuon Chea Defense Team Revisits Witness Knowledge on Koy Thuon and So Phim

The president advised that Mr. Ang’s time had run out at this point and gave the floor to Mr. Koppe. Mr. Koppe focused his questions immediately on the subject of the Koy Thuon confession tape. He asked the witness whether he could remember what Koy Thuon had said. Mr. Suoy said, “I can remember some main points only. For example, he attempted to kill Pol Pot, but that attempt was unsuccessful. Because of that failure, he gave his confession.” The defense counsel asked whether the attempt involved food poisoning, according to the tape. Mr. Suoy said that he could not recall how the attempt was carried out. Mr. Suoy then opined that food poisoning would have been the likely method.

At this point, Judge Lavergne intervened. He asked Mr. Koppe if he sought to discuss the contents of Koy Thuon’s confession. As it was obtained through torture, the judge did not see the relevance of its content. Mr. Koppe explained he did not intend to discuss the contents of the confession but simply to refresh the witness’s memory about his discussion with DC-Cam. He then moved on, asking Mr. Suoy how many people were listening to the tape. Mr. Suoy said, “There a lot of people but I don’t know the exact number. People came from different units.” Asked to hazard a guess, he said that it was less than 1,000 people; “maybe 100 people.”

Mr. Koppe asked if participants discussed the confession and if Koy Thuon was rightfully or wrongfully considered a traitor. Mr. Suoy said, “After the discussion among us, after we listened to the tape, of course we could conclude that he was a traitor. … At that time, we had to use that word during that period.” Mr. Koppe then noted that according to Mr. Suoy’s testimony to the OCIJ, the tape was played at the 1977 study session.[36] He asked the witness if this was correct. Mr. Suoy said he was “sure that the tape was played in 1976 and 1977.” On the same page of his record of OCIJ interview, Mr. Koppe continued, Mr. Suoy had testified also to hearing that So Phim was a traitor. Mr. Suoy confirmed, when asked, that this was correct.

Mr. Koppe asked the witness if he knew when So Phim died. Mr. Suoy said that he did not. Mr. Koppe advised that evidence suggested So Phim killed himself on June 3, 1978, and asked the witness if he was certain that the study session took place in 1977. Mr. Suoy said he could not state conclusively that So Phim’s name was heard at that session, although he did hear the name of Koy Thuon. When pressed, Mr. Suoy said, “I knew about [So Phim being a traitor] only through the discussion. Later on, I knew that So Phim was a traitor of the CPK.” Mr. Koppe asked about the meaning of “later on.” Mr. Suoy said that he meant discussions later on.

At this point, Mr. Koppe put it to Mr. Suoy that when he heard the tape about Koy Thuon, no one had spoken about So Phim. Mr. Suoy said, “I do not make the conclusion that Nuon Chea mentioned [So Phim’s] name, but the members of my group made a conclusion, and later on, So Phim disappeared. I did not hear Nuon Chea mentioning that So Phim was a traitor. Nuon Chea only mentioned that Koy Thuon was a traitor.”

When Mr. Chea made the latter announcement, Mr. Koppe asked, was this fact already generally known within CPK cadres? Mr. Suoy stated, “Regarding the state warehouse unit, anyone could know that Koy Thuon was a traitor because the tape of his confession was played, but I do not know about the other units.” Mr. Koppe asked whether it was fair to say that when Mr. Chea played the confession tape, “everyone already knew that Koy Thuon was a traitor.” Mr. Suoy agreed. He also confirmed that Mr. Chea never spoke personally to him about the need to uncover enemies from within.

Mr. Koppe referred the witness to his testimony concerning people being afraid when being summoned to meetings. He asked if Mr. Suoy was himself afraid when called to meetings by superiors. Mr. Suoy replied:

When we … cadres from the unit were called to attend a meeting regarding the technical work, I was not frightened at all. But when I talk about this meeting here, regarding the disappearances, there was a phone call, and according to the phone call, this person or that person was invited to attend a meeting. What I knew was that I had to inform that person to attend that meeting, and then that person disappeared, and I do not know whether that person was arrested or not.

Moving on to the warehouse itself, Mr. Koppe asked if there were two sorts of rice: rice fragments and un-husked rice. Mr. Suoy said that there were, but there were also “more items.” For instance, in Kampong Teuk Kok warehouse, items also included “fabric, shoes, garments, mosquito nets, nails” and at Kilometer 6, there was “rice, milled rice, rubber, cement.” Mr. Koppe asked whether Mr. Suoy had meant to testify that rice fragments were “solely” meant for exporting. Mr. Suoy responded, “Only milled rice was exported. … Un-milled rice was stored in the warehouse, and then that un-milled rice was milled, and the milled rice was exported”; thus, rice would be sent to the miller when rice orders were received. Mr. Koppe asked if it was true that un-husked rice was sent to the zone. Mr. Abdulhak objected and said that this was “blatantly leading” and “putting words in the witness’s mouth.”

Asking a more open question, Mr. Koppe inquired as towhat happened to un-husked rice. Mr. Suoy said, “After the un-husked rice was taken to the warehouse, I looked after the un-husked rice. That rice was not taken anywhere. If they needed rice, they would take that rice to the miller. But I am sure that un-husked rice was not exported at all.” He continued, “Many kinds of materials were sent to the zones, for example cement and salt, and other products from the factories. These products were distributed once every week. Cement and salt were distributed based on the need of those zones and sectors. … Un-husked rice was not sent to the zone at all.”

This concluded the defense counsel’s questioning, at which point the president adjourned the hearing for the day.

Hearings in the ECCC will resume on Monday, April 29, 2013, at 9 a.m. with the testimony of a civil party, TCCP 186, who is scheduled to testify for one day. TCW 752 will be a reserve witness that day.