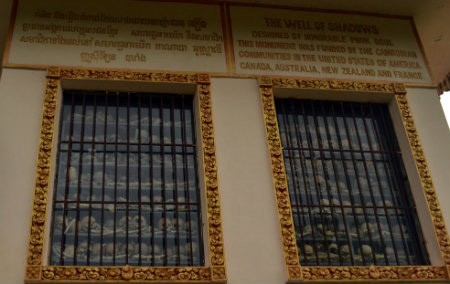

Memorials and Memories: The Well of Shadows

Situated just outside of Battambong, Cambodia, The Well of Shadows Memorial is a striking sight. Hidden in a field behind a wat sits the large rectangular structure, glass windows on its side showing that it is in fact full of human remains. Around its side, carvings depict horrendous scenes from the Democratic Kampuchea period, when the Khmer Rouge controlled the country.

Near the memorial is Wat Somrong Knong, a pagoda that was used as a regional prison and interrogation center by the Khmer Rouge. The inscription on the memorial itself states that 10,008 people were put to death here. Shockingly, local people told us that the bones and skulls that fill the memorial were excavated from the very small area of land that its foundations occupy.

When we discussed the memorial with the workers at the Pagoda, which is now functioning once again as a religious site, they told us that by and large foreign tourists visit the memorial. Relatives of the deceased do visit from time to time and lay flowers; however this was fairly rare, the worker said.

About 100 kilometers from Wat Somrong Knong, along National Highway 57, is the provincial town of Pailin. This area was held after the DK period by forces loyal to former Khmer Rouge leader Ieng Sary, who eventually defected to the government and received a royal pardon from King Norodom Sihanouk in 1996. After surrendering to the government, many of the Khmer Rouge cadres settled back into civilian life in Pailin and remain there today. Despite the demise of the Khmer Rouge, the ideals of Angkar or “the organization” still permeate the minds and attitudes of many in the area. Here we encountered a dramatically different take on recent Cambodian history.

Born in 1977, the former Khmer Rouge soldier we interviewed would have been only two years old when the Khmer Rouge lost control of most of the country in January 1979. Yet he still revered a period he repeatedly described as being free from HIV, prostitution, and crime. Still wearing his Chinese-donated Khmer Rouge jacket from the 1980s, the soldier displayed deep-seated admiration for the ideals of the Khmer Rouge and even tried to justify the mass purges committed throughout their rule and civil war.

“Cambodian society was like a farm. When a farm becomes too crowded, some of the badly behaved and undesirable animals must be killed to protect the other animals,” he said. He was also supportive of the Khmer Rouge’s efforts to eradicatd social ills. “During the Khmer Rouge, there was no prostitution, no HIV, no crime. I think this was a good thing,” he asserted. In a somewhat contradictory manner, though, he went on to state that reports of mass killings “were hard to believe.”

Speaking about whether, given the chance, he would return Cambodia to the year of the revolution in 1975, he said that despite supporting the ideals of the Khmer Rouge, he would find it a struggle to give up many of the freedoms he experiences today.

When asked about his feelings about the Khmer Rouge leadership, he replied that simply putting the responsibility on the those at the top of the regime was like “everybody going for a meal while Ta Mok pays for it,” referring to the notorious Khmer Rouge commander also known as “The Butcher” who died while awaiting trial in 2006.

Standing face to face with an ex-Khmer Rouge soldier comparing the innocent people killed by the regime to farm animals on top of an ancient pagoda overlooking the Pailin mountains made for a particularly surreal – if not all that inaccurate – metaphor for an area still housing proponents of one of the most brutal regimes of the 20th century.