Prosecution Team Completes First of Three Days of Closing Statements

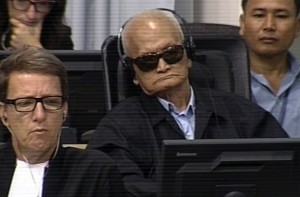

As she began the closing statements for the prosecution for Case 002/01, National Co-Prosecutor Chea Leang was thwarted by a technological glitch that set the court back 45 minutes from its 9:00 a.m. start time today. Once everything was in order, she launched into her argument and was at the podium for the remainder of the day.

The prosecution will hold the floor for the next three days. During this time, Ms. Leang and her colleague, Deputy Co-Prosecutor William Smith, will argue that the evidence has proved that “each of the accused played a unique and criminal role in a criminal enterprise that tortured and killed their fellow Cambodians.”

“This trial is about crimes that shocked the conscience of humanity,” said Ms. Leang. “Even today, countless citizens carry a heavy burden, memories of mistreatment, starvation, torture, lost ones who were killed or simply disappeared. The nation suffers from lost opportunities for education and development. A generation of skilled Cambodians was almost wiped out, killed, or forced to flee the country. The effects are still felt today.”

“This trial is important for Cambodia and also the entire world. It demonstrates that crimes of such magnitude and severity will not be forgotten,” she said. “Those responsible will be held to account.”

A factually complex criminal case with a criminal plan

Ms. Leang set the stage for her day-long monologue by declaring that the innocence or guilt of the accused can safely rely on just a portion of the crimes written in the indictments of the accused. In particular, she said she would address:

- Crimes that occurred during evacuation of various towns and cities following 17 April 1975;

- Crimes committed during the transfer of populations later in 1975-76, and;

- The mass execution of former soldiers in April 1975.

She will try to demonstrate that those crimes occurred as the result of criminal policies and in furtherance of a criminal plan that preceded and extended throughout the period of the Democratic Kampuchea (DK) regime.

“In order to understand the plan,” she said, “we must examine the history of the Khmer Rouge (KR) and acts of the accused.” She suggested that this “factually complex criminal case” shows development of a criminal plan over the course of many years.

A central question is whether the accused knew of these crimes and intended to commit them. Ms. Leang asserted that the prosecution team believes that they did, and promised to underscore sufficient evidence of their guilt. She contends that she will use both documentary and testimonial evidence to detail the crimes and show the evidence to be “non-coincidental.” Rather, the crimes were orchestrated and implemented with precision through a highly hierarchical, disciplined force commanded by the accused.

A precaution regarding political ideology versus the intentions of the accused

Ms. Leang was careful to differentiate that this is not a case about communist ideology or political ideas.

“No political philosophy is on trial in this court,” asserted Leang. “This is a case about violence, enslavement and death on a mass scale.” It is about crimes inflicted on the people of Cambodia by forces of the CPK.

On April 17, 1975, recounted Ms. Leang, the defendants led forces that created the first slave state in the modern era. They orchestrated the emptying of every urban center, herding millions of evacuees into cooperatives and stripping them of the most fundamental rights of human beings and subjecting them to appalling conditions. They ordered the complete abolition of an entire way of life by abolishing school, religion, property, and more. They oversaw elimination of groups whom they perceived as their enemies. That is the essence of the plan as outlined—criminal to its core, purpose, design, method and means, the co-prosecutor argued.

“In three years, nine months and 20 days, [this regime, with the defendants in top-level positions] caused the death of 1.7 to 2.2 million people (a quarter of the Cambodian population at the time). This trial is an attempt to provide justice for some of the victims by addressing certain crimes,” said Ms. Leang.

It is also an opportunity for the world to see the crimes in the broader context of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and to examine the role of the accused within the regime, she continued. The evidence will show, she said, that every crime committed by those forces was intended by the defendants. These men were central to the common criminal plan that was carried out.

Testimony by the defendants remains limited

Ms. Leang invited listeners to recall how, at the start of the trial, the accused said they welcomed the opportunity to set the record straight, to put forward their version of the facts and answer the allegations against them. During the trial they gave limited testimony and confirmed that they would testify again before the close of the proceedings. However, as the evidence mounted against them, both of the accused men reversed course and chose not to subject themselves to questions. This was a strategic decision to shield themselves from scrutiny and examination, Ms. Leang asserted, because they had no defense that could standup to the scrutiny.

Thus the defendants have not been tested by judges and counsel. Ms. Leang anticipates, therefore, that their eventual statements will “seek refuge from criminal responsibility though an array of accuses.” She predicts they will say that they acted with the best of intentions and that all power was held by Pol Pot. They will deny having prior knowledge of the widespread terror being perpetrated and will try to claim that they would have acted differently if they had known.

In putting forth these excuses, she said, they will embrace the same excuses put forward by every despot accused of ruining his people: it’s not his fault; others are to blame. She predicts they will invoke historical injustices that preceded DK. “They will ask you to accept that evacuating the cities was lawful, reasonable, and necessary,” she said. “Those claims amount to nothing more than demonstrable lies.”

Leang provides extensive examples in support of her assertions of premeditation

Much of the remainder of the day was devoted to an extensive review of testimony from the court proceedings in Leang’s efforts to paint the accused as the architects and supervisors of the crimes of which they are charged. “The accused played key roles. They acted willfully and with intent to commit the crimes.”

Evidence from the late 1960s and 1970s was cited as proof that the events of April 1975 were part of a continuous system of brutality and oppression created long before. This evidence was said to be extremely important because it can prove the criminal intent of the accused. In the years before 1975, they adopted a policy of eliminating perceived enemies. The events of April 1975 did not happen in a vacuum, argued Ms. Leang, they were part of the ongoing CPK policies to evacuate urban areas, enslave residents, and kill members of the Khmer public regime and other perceived enemies. Targeted groups were transferred solely by the perceived necessity to treat everyone outside the revolutionary ranks as a real or potential enemy. “Virtually the entire population was thus treated, especially those from urban areas, educated people, those who had travelled abroad, vulnerable groups, and anyone associated with the prior regime,” she said.

Ms. Leang delineated further policies known as “suffer and die” and “life and death contradiction” and the rhetoric of “smashing” the enemy. Violence defined how they came to be able to exercise and enforce their power to those outside the ranks. Much of the class struggles started with the party’s inception in 1960. For example, she noted, what is a life & death contradiction? It means that for one to prosper, the other one must die. The defendants believed that this was a fight against a system of oppression. Speaking to the judges, she said, “You must not be fooled by this lie.”

Further history from the 60s and early 70s backs assertions of a long-held plan

The co-prosecutor continued to present the historical background of the KR plan. In the 1960s, she said, the first self-defense units stated forming in the countryside. The CPK was already smashing enemies and capturing enemy soldiers. The question of what to do with enemy soldiers who weren’t outright executed was answered with the initiation of “Security Centers.” Case file shows evidence that several security centers were established from 1971-1975. Ms. Leang described party policies for sending spies there for interrogation and execution. She continued with a gruesome litany of examples from prior testimony about the party’s security center system and the generally brutal treatment of various groups (including Khmer Republic soldiers and loyalists). The CPK indoctrinated its cadres that cities were riddled with moral turpitude and inhabited by the enemy, bringing the concept known as “drying up the people from the enemy” into play.

Ms. Leang also described the Khmer cadres from Hanoi who were committee communists, but who were not to be trusted according to the CPK leadership. The Khmer cadres wanted a revolution, true, but they were associated with another country, which in the eyes of the CPK leadership was enough to condemn them to death.

Leang repeatedly cited existing evidence demonstrating how the actions of the CPK were rooted in an active history. People suspected of spying or undermining the CPK were captured and later smashed. Even within the party, members who lacked zeal were targets for brutal treatment. Enemies of the party were not killed in the heat of battle or put on trial; rather, they were summarily executed or, in party vernacular, “smashed dishonorably.”

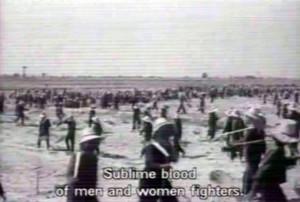

The party was also becoming increasingly adept in those years at moving large groups of people, such as in 1973 when 15,000 people were moved by the CPK, and the annihilation of Udong in 1975 as gleefully announced by defendant Samphan. “Events which were precursors to the events in Phnom Penh showed repetitive patterns that reached its climax in the evacuation of Phnom Penh,” claimed Leang. “The evidence shows a process of practicing moving people.”

To conclude this section of her remarks, Leang commented on how “All that has been reviewed here is vital to an understanding of the criminal intent behind the evacuation of Phnom Penh [by the accused].” After citing yet more examples, she said, “We submit that this evidence alone established that Samphan is lying when he said he had no knowledge whatsoever of the plan to evacuate Phnom Penh.”

She then turned to the assertion by defendant Nuon Chea that the purpose for the evacuation of Phnom Penh was “to implement an economic policy that under the extraordinary circumstances Cambodia found itself in 1975 was in the best interest of the people.” If such a thing were true, said Ms. Leang, then she wondered what has stopped him from explaining that belief in this courtroom?

“These claims have absolutely no basis in reality,” she said. “We will expose them for what they are: dishonest, deceitful, self-serving assertions” that these defendants think can shield them from their criminal responsibility. “It had nothing to do with addressing a genuine humanitarian crisis. Instead, the evacuations were designed to suppress and subjugate the population, and identify those who qualified for immediate execution or to strip others of their rights.”

After a brief pause to change the audiotape, Ms. Leang touched on what she said was another “explanation” for the need for evacuation: Worried about incitement by the American CIA, the CPK leadership carried out the evacuation order to deal with an enemy that might have attacked.

After the evacuation, criminal acts continue

Regardless why the evacuation seemed necessary, Me. Leang argued, Pol Pot decided against a policy of reconciliation, seeing city people as ipso facto collaborators. All evacuees who survived the first wave were then subjected to a regime of persecution and terror as reflected in their being labelling “new” or “17April” people. They were then forced either to work for those in power or be killed. It was made clear that the evacuees were the property of Angkar.

Ms. Leang then spent considerable time reviewing the actual siege and eventual surrender of Phnom Penh, noting in videos and photos the short-lived joy of the civilian population. Although the Khmer Republic government sought a peaceful end to the war, the offer was explicitly rejected by the CPK on numerous occasions and, of course, darker times arrived.

Ms. Leang ended the morning exposition by quoting extensively from Sydney Schanberg’s diary recounting the first few days after the CPK entered the city.

The aftermath of the CPK’s march into Phnom Penh

Upon returning from the lunch break, Ms. Leang delved into a recounting of the situation faced by high-ranking government and military and police officers from the Khmer Republic regime after the CCPK “liberated” the city. Essentially, they were briefly given the opportunity to join the National United Front of Kampuchea (FUNK), but those who did not join the revolution immediately were placed in the same category as the super-traitors. Of course, senior city officers were deemed traitors and it was necessary to kill them; in the days following the fall of Phnom Penh, thousands of officers were murdered in cold blood by Khmer Rouge forces in an organized and systematic operation, she said.

The co-prosecutor stated that the surrender of the Khmer Republic regime and arrest and execution of senior members of that regime set the stage for all of the horrors and criminal acts to come in the forced evacuation of the city, which she went on to address in depth later. In her remarks, she relied heavily on the writings of three observers: the diary of Sydney Schanberg, the diary of John Swain and testimony of the photographer, Al Rockoff, as well as Cambodian journalist Dith Prahn.

According to Mr. Schanberg, the Khmer Republic ministers spoke of feeling abandoned and without material means to move forward. The government agreed to surrender near dawn on 17April1975. When the president of the super-council of the Khmer Republic surrendered, committing to an immediate transfer of power, he asked only for no reprisals. His offer was not accepted. The Prime Minister was at some point taken out and executed.

“Only terror was to follow,” recounted Ms. Leang in her long day of reviewing the evidence against defendants Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan. She retraced the “ruthlessness and single-mindedness and lack of concern for human value human suffering for individual values shown during the evacuation.” Upon citing three additional anecdotes of this violence, she said, “Of course, all came to know the truth in due course.”

Moving the masses—the Phnom Penh evacuation and aftermath

Co-prosecutor Leang explained that the CPK knew that moving the millions of people in Phnom Penh would inevitably cause great difficulties (and even death), yet they provided no assistance to the evacuees, not even for those who were reasonably ill or struggling. Everyone was left to his or her own.

After a brief mid-afternoon break, Ms. Leang resumed by discussing the CPK’s refusal of all offers of international assistance. The phrase “you have to rely on yourself,” was put into play, as testified to by one former member of the cadre. People were abandoned with medical difficulties (including one patient who was in mid-surgery when the doctor was forced to leave) or IV drips in their arms. And such stories went on, and on.

“Such actions could only have been intentional mistreatment,” remarked Ms. Leang. “The death of thousands was not only foreseeable, but inevitable.” Many dreadful stories were offered as a review of the testimony, and yet it was also reported that the defendant Samphan praised his forces, calling them “liberators.’ In his words, according to Ms. Leang, he said joyfully that, “The enemy died in agony.”

Ms. Leang reminded the court that the forced evacuation alone caused some 20,000 deaths in total. In one empirical study, some 10,000 people died en route and another 10,000 died in executions during the evacuations. There were extensive reports of civilians killed for refusing to leave their home, not leaving fast enough, for bringing too many personal belongings or simply for disregarding orders, she said.

The other forced evacuations

Although there was an evacuation known as “the 2nd Forced Transfer,” there should not be the impression, said Ms. Leang, that there were only two forced transfers. “The truth is that it was a continuing policy.” People were moved consistently in the months after the CPK’s victory and the Second Transfer was merely a continuation of a series of such crimes. She said, “New people who were already the victims of crimes on and after 17 April 1975 were again targeted for systemic discrimination and mistreatment. They had already suffered from forced labor and inhumane conditions and suffered enslavement. Thousands had already died from overwork, starvation and disease. As a group they were subjugated and suppressed. They were not flesh and bone, but units of production. They had no value as human beings.”

So much testimony to the suffering occurred, and so many elements (such as the implementation of the rice harvest quotas) were established that Ms. Leang cannot recount them all. And yet she continued to tie one story to another. For example, after mentioning the above stories, she reports that the defendant Samphan was reported as asserting at one point that the second forced transfer was an economic program to manage the food crisis.

“Look at the reality of what happened to the victims,” she inserted, “not at this disingenuous rhetoric used by the party for forwarding their mission.”

There followed additional statements about the CPK operatives building collectives and building the market and agricultural basis for the nation. When needed, assets (people) were moved, sometimes on the order of 400,000 or 500,000 at time, ostensibly in an attempt to reduce food shortages. The CPK had to know, Ms. Leang posited, that moving that many people in such a short time would exacerbate the food crisis. “How could they be expected to survive?” she asked.

The proceedings were adjourned for the day at 4:00p.m.

The prosecutors will continue their closing statements tomorrow, Friday, October 18, 2013.