Sentencing Requests Cap End of Prosecution’s Closing Statements

The final of three days allocated to the prosecution had a watery start with floodwaters hampering access to the grounds of the ECCC. After wading ashore, participants were greeted with a continuation of Friday’s detailed review of testimony in support of the prosecution’s case in trial 002/1 by Deputy Co-Prosecutor William Smith.

The court was called to order at 9:05 a.m. with Khieu Samphan in the courtroom and Nuon Chea observing the proceedings from the court’s holding cell in deference to his health concerns. President Nonn invited Deputy Co-Prosecutor William Smith to regain the thread of his closing statements from where he left off on Friday.

Mr. Smith indicated that he would frame today’s remarks in four parts. First, the plan is to finalize submissions on demonstrations of power and authority exercised by the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) party center. Second, the prosecutor will examine the roles of the accused in the CPK and Democratic Kampuchea (DK) power structures, and assess the true nature of their characters. Third, he will demonstrate how the individual contributions of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan contributed to the policies and crimes as charged. Fourth and finally, he and his colleague, Ms. Leung, will request the sentence that Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan should receive for their crimes in this trial.

Mr. Smith indicated that he would frame today’s remarks in four parts. First, the plan is to finalize submissions on demonstrations of power and authority exercised by the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) party center. Second, the prosecutor will examine the roles of the accused in the CPK and Democratic Kampuchea (DK) power structures, and assess the true nature of their characters. Third, he will demonstrate how the individual contributions of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan contributed to the policies and crimes as charged. Fourth and finally, he and his colleague, Ms. Leung, will request the sentence that Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan should receive for their crimes in this trial.

On Friday, he reminded listeners, he completed his demonstration of how CPK party center exercised control and authority over the zones, and how this was evidenced in various communications, including the Revolutionary Flag. Regarding people killed, Smith reminded listeners, “We are not talking about wartime enemies. These so-called enemies were fellow Cambodians that Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan believed should be killed.” The blame for the killing, said Smith, was not on “autonomous individuals. They were just doing what party leaders wanted,” if one believes the testimony.

The level of control enjoyed by the standing committee

Next, Mr. Smith began his examination of standing committee meetings in order demonstrate the level of control it exerted over policies in the zones. During the trial, the defense sought to downplay the importance of the Standing Committee, asserting it was involved only on a superficial level. “The way to debunk this defense is to look at a few examples of the meeting minutes,” asserted Mr. Smith, who then quoted a few decisions of the Standing Committee that refute the defense’s assertions.

One refutation earned Mr. Smith’s wry comment that, rather than vague involvement with the zones and cadres, the standing committee was very precise, indeed—starting with the title of one copy of meeting minutes: “Certain Concrete Measures.” The text used very specific terms to describe ways to protect the border with Vietnam by using spikes, including the number and length of those to be used.

Another memo title, “Issues in the abstract” also earned the comment from Mr. Smith that it is clearly a misrepresentation of the facts, and that there wasn’t much about the documents that is abstract. “They made concrete decisions that resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of people,” he said as he went on to show many more examples.

One August 1975 document included the instruction of what to do with the empty cities. The directive suggests that (among other things) strategic crops such as coconuts should be planted in the cities but that banana trees should not be, “since they spoil the beauty.”

There were documents regarding economic matters (including specifics on increasing salt production). Others called for adolescent children from the base areas to be handed over to industry” and still others involved decisions about the amount of rice taken by Angkar from the various regions, and the use of water. In one document, Nuon Chea instructed that “certain words should be taken out of songs” because they too-resembled old songs or rhythms associated with life before the DK.

The 13 March, 1976 meeting minutes were with regards to the resignation of Sihanouk. It was decided they would let him live but that he would have to leave the country. The memo also records that they decided to lure his children back into the country so they could be killed. (For much of the closing arguments, Mr. Smith caused this original piece of information to remain posted on the overhead cameras.)

There followed discussion about Khieu Samphan’s attendance at the party meetings. Although the defendant contended his attendance was very sporadic, the co-prosecutor pointed out that, of the 19 surviving meeting minutes, Khieu Samphan was present for 16, an 84% attendance rate. During the trial, Khieu Samphan asked this chamber to conclude that he only attended 4% of the meetings over the course of the DK period. “What a remarkable twist of fate or unfortunate coincidence,” hinted Mr. Smith, “that of the minutes destroyed all were meetings he [Khieu Samphan] did not attend.”

“Your honors, the only reasonable conclusion from Khieu Samphan’s testimony and the high percentage of meetings he attended in the surviving minutes is that he was a regular attendee of the Standing Committee during the DK period.”

Mr. Smith then offered two more facts intended to demonstrate definite assertion of control.

Zones, he said, were not allowed to engage in direct communication with other zones. He quoted from a projected image on the screen, which showed how communications were always directed via the center, testimony which corroborated other evidence of requests that information be forwarded from the center to other zones. These facts “prove the knowledge and control of all events over all regions and all zones in DK” by the party center, including the accused, asserted Mr. Smith.

He then went on to assess the roles played by Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, and the character traits they displayed. This evidence, said Mr. Smith, is critical to understanding the intentions of the accused and to refute the assertions of the defense in the trial regarding their lack of participation in the crimes.

“Who is Nuon Chea?”

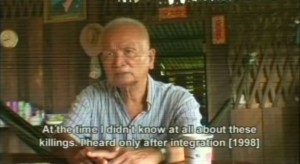

“Humans have many layers, and the face of a killer can be hard to see,” began Mr. Smith. “Those responsible for death on a large scale rarely reveal their darkest side in public.” He then showed videotape of interviews and revisited witness testimony in an effort to show the court how “political leaders may profess to love their countries but still be capable of horrific crimes.” For example, when asked if he was disturbed by the executions of former comrades and friends, Nuon Chea said, “the party decided to kill them because they were betraying the party and nation. I was not scared or sad when they were killed. They had done wrong…we were friends, but friendship and political work are separate.”

Mr. Smith continued to show video interviews and use other evidence to demonstrate Nuon Chea’s character as an extremist to this day. He said, “It is through their extremism that Nuon Chea and other members of CPK crossed the line from revolutionaries to war criminals responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Cambodians.”

He also pointed out assertions made by Nuon Chea, in a videotaped interview with videographer Thet Sambath, that he had no intention to be equally forthcoming with this court. In addition, Mr. Smith pointed to examples of Nuon Chea denying any military role with the CPK. Nuon Chea said instead that he was only on the legislative side, even though, as Mr. Smith pointed out, Nuon Chea himself has admitted that this defense is a lie in this statement: “There was nothing to debate because we had no laws to pass.”

Regarding Nuon Chea’s general character, Mr. Smith reported that Nuon Chea has frequently asserted he is not an intellectual. “This is perhaps the saddest and most desperate of lies,” said Mr. Smith, who summed up a resume for Nuon Chea that include studying law at most prestigious law school in Thailand, being fluent in at least three languages, and sitting across the table from the leaders of China and other countries. He also prepared the original statute for Cambodia. “He was not an intellectual weakling,” argued Mr. Smith. “It defies logic and reason to claim he not an intellectual, and yet at the same time claim that his principle role in the CPK was to educate the CPK cadre on those policies. How is it possible to educate cadres on policies if you don’t understand them yourself?”

Regarding Nuon Chea’s general character, Mr. Smith reported that Nuon Chea has frequently asserted he is not an intellectual. “This is perhaps the saddest and most desperate of lies,” said Mr. Smith, who summed up a resume for Nuon Chea that include studying law at most prestigious law school in Thailand, being fluent in at least three languages, and sitting across the table from the leaders of China and other countries. He also prepared the original statute for Cambodia. “He was not an intellectual weakling,” argued Mr. Smith. “It defies logic and reason to claim he not an intellectual, and yet at the same time claim that his principle role in the CPK was to educate the CPK cadre on those policies. How is it possible to educate cadres on policies if you don’t understand them yourself?”

Nuon Chea also denies being known as “Brother #2” in his closing arguments, although references to him as “Brother #2” are abundant in the evidence. Two additional video clips show Nuon Chea claiming “no remorse,” and saying, “if they have evidence to convict me that’s fine, that’s justice.”

And who is Khieu Samphan?

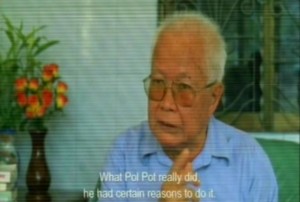

Next up for presentation was the role and character of Khieu Samphan before, during and after the DK period in order “to understand the level of his responsibility and whether his defense is believable,” said Mr. Smith.

Who is Khieu Samphan? He claims to be a man “who fell into the party by accident,” yet he rose to the highest levels of the CPK. Mr. Smith said Khieu Samphan presents himself as a man of integrity, but also as someone who said he did not ask questions at party headquarters because he respected the CPK rule of secrecy. He claimed that if he was surrounded by mass murder, he was unaware of it, “the only man in Cambodia who saw nothing, heard nothing, knew nothing,” commented Mr. Smith.

He went on to say that “the reality paints a picture of a different man, an educated man who had a thirst for absolute power.” That Khieu Samphan used his public image to flaunt the great successes of his party and to attract legitimacy for the CPK. This “man of integrity,” said Mr. Smith, “rejected reports of atrocities as slanderous campaigns but today he stands before you and says, ‘I knew nothing.’” Mr. Smith displayed videos and excerpts from Khieu Samphan’s 2004 book to underscore his points.

In 2001, in an open letter by Khieu Samphan, he asked for forgiveness for his naiveté, saying he thought the events of the 1970s were about national survival, that he hadn’t understood it would lead to such killings. In response, Mr. Smith asserted that “Khieu Samphan was no fool. He shared Pol Pot’s vision. That was why he was trusted, and a leader for some 28 years.” His evidence included relaying the facts that Khieu Samphan held several positions: party center, public face of the regime, direct involvement in forced labor, direct role in the establishment of DK. He was its head of state, and oversaw Sihanouk’s house arrest. And so on. In a 1987 publication, Khieu Samphan compared the death toll from the DK as being less than the number of deaths of car accidents in other countries, Mr. Smith stated.

In 2001, in an open letter by Khieu Samphan, he asked for forgiveness for his naiveté, saying he thought the events of the 1970s were about national survival, that he hadn’t understood it would lead to such killings. In response, Mr. Smith asserted that “Khieu Samphan was no fool. He shared Pol Pot’s vision. That was why he was trusted, and a leader for some 28 years.” His evidence included relaying the facts that Khieu Samphan held several positions: party center, public face of the regime, direct involvement in forced labor, direct role in the establishment of DK. He was its head of state, and oversaw Sihanouk’s house arrest. And so on. In a 1987 publication, Khieu Samphan compared the death toll from the DK as being less than the number of deaths of car accidents in other countries, Mr. Smith stated.

“This evidence is a reliable path to his mind: arrogant, unrepentant, and unapologetic,” claimed Mr. Smith. Even after 1979, Khieu Samphan fought for the party’s return to power for almost 20 years before surrendering in 1998.

At this point chamber president Nonn agreed with Mr. Smith that it seemed a good time for the mid-morning break.

Proving a few issues “beyond a reasonable doubt”

After the break, Mr. Smith spent a bit more than an hour digging into the evidence underlying the contributions made by Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea toward the crimes alleged in their indictments, beginning with the forced transfers from Phnom Penh and including killings and inhumane treatment committed during that evacuation. He showed how the evidence has proven beyond a reasonable doubt that both Nuon Chea & Khieu Samphan participated in the meetings of the CPK leadership when it was unanimously decided that residents would be forced to leave the cities when CPK assumed power. He reminded the court of how Nuon Chea admitted in this courtroom in November, 2011 that the decision to evacuate was made at a meeting of the party leaders held in mid-1975. This plan, he said, is referenced in numerous issues of Revolutionary Flag, which he then named in detail.

Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan both admitted in the trial that they were at an April, 1975 meeting at the B-5 base in Kompong Chhnang Province. The subject at hand was the liberation and evacuation of Phnom Penh. Smith reviewed the group’s adherence to collective decision-making procedures, and how decisions were unanimous about both military and evacuation measures. His purpose was to show the shared knowledge and intent of the accused to implement the plans. According to Mr. Smith, the decision to evacuate Phnom Penh had nothing to do with the food situation or the threat of American bombing. “It was a strategy used by the CPK leaders,” he said, “to treat the Cambodian population as the property of the CPK, to force them to work without payment in inhumane conditions, and denied even the most basic human rights.” And, said Mr. Smith, even if Khieu Samphan claims no large role at B5 or at the other bases, he was a senior member of the group behind the attacks and evacuations. Mr. Smith repeated for the court once again the evidence indicated the intention to “smash” officials and eliminate Lon Nol officials and soldiers, reiterating the defendant’s criminal responsibility for decisions including the elimination of Lon Nol officials as well as violence against citizens. This evidence included speeches and statements by Khieu Samphan, all of which, said Mr. Smith, were in “the words of a man who accepted his role.”

A review of the Second Forced Transfer

Mr. Smith then took time to review Ms. Leang’s recap of the testimony regarding the second forced transfer in September 1975 with an eye for how it was the direct responsibility of the CPK leaders. “When they established the first slave state of the modern era, they ran it under the watchful eye of the CPK leadership through January 7, 1979. All crimes were designed by the accused through a rigid hierarchy where cadres received orders from party center. All orders emanated from the top,” reiterated Mr. Smith—including Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan. At the bottom were those subjected to the CPK’s “rule of terror.” As evidenced by the testimony, 99% of the population lived under the slave state.

And then came the second forced transfer, another part of the plan. It became apparent, according to the testimony, that 400,000 to 500,000 people were needed in the Northwest Zone. Documents reviewed show how closely leaders were informed of such situations in the zones. The people had no freedom of movement, contained as they were in cooperatives so they couldn’t move freely.

Yet in documents that showed problems (such as illnesses or food shortages), there is no evidence of efforts to ameliorate those problems. Any discussion of helping the slaves was directed solely at insuring that they would not want to go anywhere. In other words, one source, while acknowledging these people were their prisoners and slaves, said that food would help because if you “feed them, they no longer desire to go anywhere else.”

Persecution continues

Regarding leadership’s continuing intent to persecute the new people, Mr. Smith worked to demonstrate criminal intent in different ways. The basic plan, he said, was that new people were to be subjugated in order deploy their strength to work. According to David Chandler’s testimony regarding the classification of people, it was a process of “us and them,” the “winners and losers” the “revolutionaries and the people they defeated.” The language is enigmatic, but, as Mr. Smith said, “One must not look simply at the words employed by the leaders. One must look at the system of terror they put into place.” The movement isn’t about caring for the people, but rather simply a decision to create misery “on a colossal scale.” The purges continued as long as people continued to flee. And, according to Mr., Smith, all members of the party center were aware of this decision. There is no evidence that they distanced themselves from it or tried to stop it.

There followed lengthy scrutiny of the item of evidence known as Document 3. Mr. Smith’s stated goal was to show part-by-part evidence of participation in party leadership, in making the decisions needed to implement a centrally devised plan involving the forced movement of people, rice harvest, etc. Document 3 also shows Khieu Samphan’s involvement through his role with the Ministry of Commerce in the second forced transfer, his supervision at the ministry of commerce, how he regularly visited the rice storehouse, and gave workers instructions. The point was that no one other than party center had authority to address the matters of importance the document contained.

At this point the lunch break was called, with the court called back into session at 1:30 p.m. Mr. Smith spent a few more minutes addressing what the court could learn from Document 3 before turning to an exploration of the role of the Ministry of Commerce and Khieu Samphan’s further involvement in maintaining the slave state.

Rice quotas and the slave state

With the nation needing such items as military supplies and ordnance, the party central, reported Mr. Smith, upped the rice quota to unrealistic levels while eroding social services such as adequate food and health care for the people. Despite the starvation reported by numerous sources, produce was stored, then exported, despite the fact that people were starving to death. The need to grow more rice led to the second forced evacuation so that there would be workers available in the north.

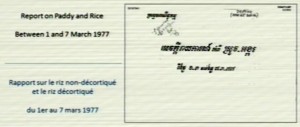

Rice production was elevated to “break-neck” speed. The 1977 quota was revised in November 1975 (to be applied in 1976) and demanded a huge production increase, up to 3 tons/hectare regardless of whether the paddy was a two-season or single-season plot of land. But, asserted Mr. Smith, the underlying considerations relevant to the party central had more to do with the on-going enslavement of people (all of the “new” or “17 April” people) as well. Their arrival in the Northwest zone landed them that much further from home.

Rice production was elevated to “break-neck” speed. The 1977 quota was revised in November 1975 (to be applied in 1976) and demanded a huge production increase, up to 3 tons/hectare regardless of whether the paddy was a two-season or single-season plot of land. But, asserted Mr. Smith, the underlying considerations relevant to the party central had more to do with the on-going enslavement of people (all of the “new” or “17 April” people) as well. Their arrival in the Northwest zone landed them that much further from home.

Mr. Smith integrated the comments about the forced transfer and food production with the observation of Khieu Samphan’s boasting about how all work was being done by hand. “Though barehanded, they can do anything,” he is reported to have said. In addition, the use of children as workers was celebrated. There were no longer any schools, and children worked as soon as they were able, and Khieu Samphan is also quoted a saying, “But they [the children] are joyful” and “They are well-trained in manual labor and farm chores.”

The matter of food for the people

Mr. Smith turned his attention to the facts surrounding nourishment. With food rations allocated by the state, but rice needed for export, what was said by the leadership was different from the reality. According to one source, Nuon Chea “boasted” about determination of food rations for workers, that one should get 20-30 kg of rice per month, depending on the “nature of the person.” Yet Mr. Smith also pointed out the testimony of one of the civil parties, who said they were lucky to have one tin of rice for 40 persons.

Nuon Chea’s “claim of sufficient food rations was a lie,” stated Mr. Smith. “Nuon Chea’s statement was made at a time when millions were suffering starvation.” That the second forced transfer occurred when it did made matters worse. There had just been a “wholly-inadequate” harvest in the northwest, according to one source, and that region was unprepared to absorb so many people.

Given the theme of enslavement and treatment of the people, Mr. Smith spoke finally how, “Cambodians were no longer individual human beings. They were soulless instruments in the working out of a grand national design.”

Getting rid of Enemy #1

Mr. Smith’s commentary then turned to a discussion of Toul Po Chrey with regards to the responsibility borne by Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan for what happened there. Clearly, said the co-prosecutor, it was part of a broad joint criminal enterprise in which Khmer Republic officials and soldiers (and their families) were Enemy #1. At the baseline of his comments was Mr. Smith’s assertion that “evidence has proven beyond a reasonable doubt that Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan agreed to and knew of the Lon Nol group to be searched out and eliminated.” It was a core party line—one that Nuon Chea himself confirmed in 1977.

Nuon Chea admitted to years of building secret defense units, as far back as 1961. The goal was to covertly “smash” government infiltrators and agencies such as the CIA and KGB.

Mr. Smith added that, “had the CPK’s use of extrajudicial violence stopped on 17 April, we would not be here. But, however, it accelerated.” Khieu Samphan, said Mr. Smith, knew the arrests and killings continued after the Lon Nol were defeated. Yet he tried to tell the court he knew nothing about them, leading Mr. Smith to say that was “the most incredulous of all lies.” Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea had daily reports. They lived together. Khieu Samphan was at the meetings where reports were made. He was fully informed about all of the policies of the party. “He lied,” said Mr. Smith, because he has much to hide. He is deeply involved.”

Nuon Chea also made it clear, said Mr. Smith, that he had knowledge as well. Showing a video demonstrating this, Mr. Smith pointed out that Nuon Chea also stated that the killings were the correct solution. There was no way to keep those people prisoners, said Nuon Chea. “If we kept them they would spread their eggs and many more would have been killed.”

For his part, Khieu Samphan made speeches during the DK regime regarding CPK policies on enemies, how they were everywhere and needed to be eliminated, according to Mr. Smith.

Mr. Smith concludes his review of the evidence

After the mid-afternoon break, at 3:00 p.m., Mr. Smith turned the attention of the court away from the extensive review of testimony pertinent to his closing remarks in favor of identifying more than 20 separate points, supported with evidence, that demonstrated discussions and decisions of party leaders on the topic of people accused as enemies and what to do about them. In one set of meeting minutes from March 1976, the group discussed how to deal with Prince Sihanouk (specifically whether or not he should be killed), and what to do about his children. Enemies in the North Zone were discussed, as well as whether or not to arrest and execute certain high-ranking zone & cadre members who had come under suspicion. There was evidence reviewed of orders signed by Khieu Samphan for the execution of top leaders of the Khmer Republic, and of Nuon Chea’s participation in the arrest and execution of certain parties at S-21. Mr. Smith also reminded the court how, “these members of the JCE used direct perpetrators (namely CPK cadres and members of the military) to commit all the crimes with which they are charged.”

“Your Honors,” said Mr. Smith, “The evidence proves beyond a reasonable doubt that Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan agreed with and contributed to the policy to eliminate enemies of the party.”

In particular, Mr. Smith reviewed the efforts as far back as 1969 by Nuon Chea and others to focus attacks on the Lon Nol government. In one 1973 document quoting Khieu Samphan, he refers to them as “a treacherous clique and regime of traitors.” Mr. Smith reminded the court of the CPK view of Lon Nol personnel as “life and death enemies.” And according to an admission made at trial by Ieng Sary, CPK leaders decided to broaden the scope of execution orders after 17 April 1975 to “keep that group from being able to rise up and oppose the revolution.” Mr. Smith also offered evidentiary statements telling how, “if they were arrested, they [Lon Nol soldiers] were to be smashed.”

“It is crystal clear,” concluded Mr. Smith in this regard, “why this group was subject to mass killings at Tuol Po Chrey,” And he reviewed testimony supporting the contention that such killings were not done by autonomous parties, but as a result of a centrally directed policy against those persons.

Khmer Republic soldiers were also one of the primary groups of prisoners in the early days of S-21, according to testimony by Duch, where Nuon Chea had general oversight and responsibility. In addition to former Khmer Republic soldiers and officials, their families were also taken to S-21—and as corroborated by one prisoner list, 152 were “smashed,” and nine died of illness, including 13 relatives.

Again came Mr. Smith’s increasingly familiar refrain: “Your honors, the evidence proves without a reasonable doubt that former Khmer Republic personnel were targeted for execution.”

Mr. Smith concludes his remarks

“In conclusion,” he began, “we submit that these accused are criminally responsible for all the crimes for which they are charged.” After listing the charges, he continued, “”the accused are guilty of these crimes because of their membership in and significant contributions to a systematic joint criminal enterprise (JCE), one that began before 17 April, 1975 and lasted until 7 January, 1979 when these accused were ousted from power.”

Mr. Smith then listed the members of the JCE, accusing them of “systematic enslavement and persecution of and inhumane treatment of Cambodia’s civilian urban population (described as ‘new’ people or ‘17 April’ people). These victims were suppressed, subjugated and punished in a nationwide system of ill treatment.

“The evidence establishes that members of the JCE intended each and every crime with which they are charged,” he asserted. “These crimes were the immediate and direct result of the JCE. They were implemented through a highly organized, hierarchical and disciplined authority structure and commanded by the CPK party center.”

He then listed the defendants’ key contributions to the JCE:

- Participating in creation and enforcement of the CPK policy to target suspected enemies, including Khmer Republic officials, through imprisonment, torture, and extrajudicial killing;

- Participation in unanimous decisions of the party center to forcibly transfer the population of Phnom Penh at meetings in June 1974 and April 1975;

- Issuing specific directives to Khmer Rouge divisions to evacuate Phnom Penh at the April 1975 meeting;

- Ordering, directing, and indoctrinating CPK cadres and the military to commit crimes, including evacuation of cities, enslavement of the civilian population and searching for and executing suspected enemies;

- Encouraging and approving the commission of crimes through CPK propaganda (including the Revolutionary Flag and circulars);

- Personally encouraging, directing, and endorsing commission of crimes through speeches, interviews, and public statements calling for the execution of enemies and calling for the enforced transfer of forced labor;

- Supervising and maintaining oversight over all civilian and military cadres involved in the crimes through a system of regular meetings and directives from party center and detailed written reports from the zones and autonomous sectors;

- Participating in the decisions of the party center between May-Sep 1975 to continue the enslavement of the urban population and the use of forced labor and inhumane treatment and specifically to transfer 500,000 people to the northwest and 20,000 people to the north zones;

- Coordinating and monitoring the second forced transfer;

- Maintaining the system of enslavement, persecution and inhumane treatment, forced transfers and targeting of enemies until the end of the period covered by the closing order;

- Prohibiting the return of the enslaved population to their homes, and;

- Making false statements designed to conceal the crimes, thereby shielding direct perpetrators.

Mr. Smith’s final statements took a look at which systematic form of the JCE would be the most appropriate legal characterization of the accused’s mode of liability in this case, “because this case is the very definition of an ongoing system of violence and ill-treatment directed at a civilian population.” He suggested the second systematic form.

“However, should your honors be minded to apply the first form of JCE,” he went on, “we submit that the evidence meets that form of liability as well because all of the crimes committed were part of a JCE and intended by these accused.”

Either way, he suggested, these modes of liability are “clearly established beyond a reasonable doubt on the facts I have just described on the evidence before you. And in the alternative, the accused are criminally responsible for the crimes as the superiors of the direct perpetrators, who failed to prevent or punish their subordinates when they knew crimes were about to be or had been committed.”

Smith contended once more how the evidence proved beyond a reasonable doubt that, as members of the party center, both Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan had effective command and control over the perpetrators, with they had the ability to take steps to punish the perpetrators. “But they failed to take any steps to prevent these crimes or punish the perpetrators. In fact, they used their position and authority to shield the perpetrators from any punishment.”

The prosecution’s request for sentencing

At approximately 3:15 p.m., anticipation by the more than 400 observers in house today of the prosecution’s final task was rewarded when Mr. Smith indicated that he was, at last, ready to cede the floor to his colleague, Ms. Leang, who would read the sentencing request.

At approximately 3:15 p.m., anticipation by the more than 400 observers in house today of the prosecution’s final task was rewarded when Mr. Smith indicated that he was, at last, ready to cede the floor to his colleague, Ms. Leang, who would read the sentencing request.

At that time, Chamber president Nonn asked that Nuon Chea be brought from his holding cell to be physically present for the reading of the sentencing request according to court rules. When Nuon Chea was seated, Ms. Leang began her final presentation.

She began by reasserting that the prosecutions efforts have not strayed from the basis of the severance order of the trial chamber. She said that the prosecution is of the view that Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan must be held responsible for all these crimes which were committed within the scope of 002/01 in their capacities as senior leaders of the CPK regime. She reviewed the five high-level CPK policies in question:

- Forcing population movements from the cities to the countryside and from other regions;

- Establishing and maintaining the profits at the cooperatives;

- The re-education of “bad elements” and killing of “enemies” inside and outside of the party ranks;

- Special measures taken against targeted groups, including Cham, Vietnamese, Buddhist, former officers of the Khmer Republic, including civil servants, military officers and their families, and;

- Order and regulation of false marriage.

These policies, she said, were successfully implemented and are related to the charges within the scope of this case. “The prosecution is of the opinion that based on the evidence, including telegrams, videos, witness and expert testimonies,” said Ms. Leang, “they all show clearly that the two accused have knowledge and have actively participated in the implementation of the CPK’s plans, which cost millions of deaths of Cambodian people within the three years, eight months, 28 day period.”

Then, with an eloquent flair, Ms. Leang said:

We do not ask for the killing of these two accused. We do not ask you to condemn these men and their entire families, to be thrown out of their homes, to be force-marched under the hot sun for days at a time, to be left in the wilderness to toil and starve in an organized system of enslavement. To be abused and beaten. To be lied to and deceived, to be bound and shot. To watch their children be torn apart and smashed against trees and their loved ones perish without even the dignity of funeral rites-as the two accused and their co-perpetrators committed on the victims.

Today on behalf of the Cambodian people and the international community, we ask you for justice, justice for the victims who perished and justice for the victims who survived, who had to live through such a vicious and cruel regime under the leadership of these two accused and other leaders. We ask you to punish the two accused according to the law.

The accused, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan have failed to express remorse or regret for the crimes committed under the leadership of the CPK and DK regime. Khieu Samphan does not cooperate with the court to seek the truth to give justice to the victims. On the contrary, the accused Nuon Chea expressed anger through his words that rotten wood should not be carved into a Buddha statue [upon listening to a certain testimony earlier in the case]. As for Khieu Samphan he stated, ‘let bygones be bygones.’ The accused Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan lied and do not take the responsibility toward the evidence put before this court…Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan must be responsible for all those crimes. We have sufficient evidence before you in accordance to Article 5, 29 (new) and 39 (new) a law to establish in the ECCC to prosecute crimes committed during the DK regime.

The prosecution requests the trial chamber and your honors to punish the accused Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan for life imprisonment which is the only punishment that they deserve, and that is the international standard for these crimes as well. Thank you.

Anti-climactic housekeeping details

The chairman noted that the time allocated for prosecution was complete, but also that another matter delayed due to the late morning arrival of a member of the court (perhaps due to the flooded parking lot) needed attention. At this point, the court duly recognized a new international lawyer for the civil party. After she was sworn in, court was adjourned at 3:50 p.m. On Tuesday, October 22 at 9:00 a.m. the chamber will give the floor to Nuon Chea’s defense to present their closing statements in Case 002/01.