Nuon Chea’s Defense Urges Acquittal On All Charges

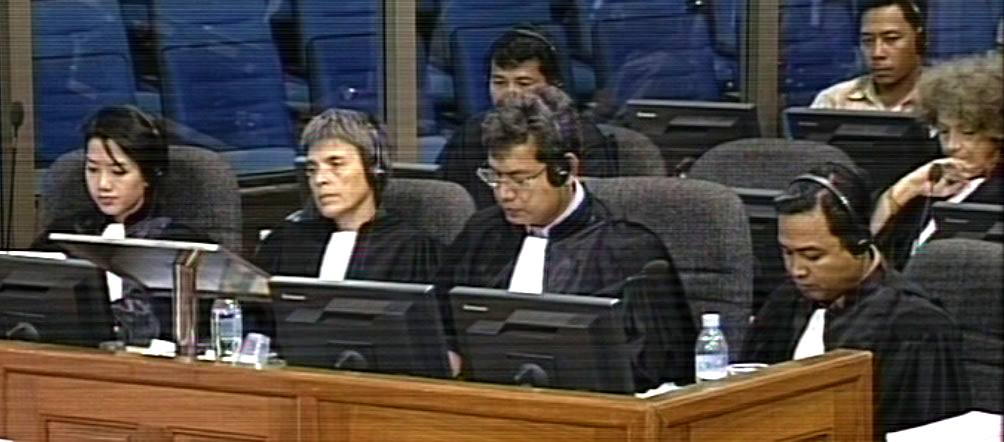

Victor Koppe, Co-Lead Lawyer for Nuon Chea, returned to center stage today for the defense’s second and final day of closing statements in Case 002/01. His client viewed the proceedings from his audiovisually equipped holding cell on the level below the chamber, as has been his habit due to health concerns. Co-defendant Khieu Samphan joined 40-plus others in the ECCC chamber, with a small crowd of mostly students in attendance in the gallery for the morning session.

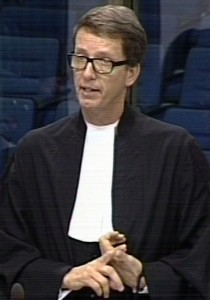

Mr. Koppe launched into his statements with the same intensity he demonstrated on Tuesday. For his part today, Koppe said he would begin with an examination of the evidence presented regarding his client’s lack of intent to cause harm to Lon Nol soldiers in 1975, along with his observations that there are significant issues regarding a fair trial for his client. He then planned to demonstrate the incomplete nature of the prosecution’s Toul Po Chrey evidence, followed with substantiation that, even if the Toul Po Chrey executions did occur, no one at party center intended them as alleged. As time would tell, Mr. Koppe’s delivery would fill the morning session entirely.

All of what he was about to say, Koppe asserted, would be “enough to establish that Nuon Chea is not guilty of the crimes with which he is charged.”

“Scatter” is not the same as “smash”

Mr. Koppe first took to task the prosecution’s argument that the CPK entered Phnom Penh in April 1975 with a centralized decision intending harm to Khmer Republic soldiers. He criticized the prosecution’s reliance on a solitary witness, Phy Phum. When asked if CPK forces “sought out” Lon Nol personnel, Phy Phum said, “No, because they [Lon Nol soldiers] had raised white flags already. There were clear instructions not to touch them. During war, on the battlefield, that was different. Now they had surrendered to us and we need not touch them. They are Cambodians just like us. Those were the words of Pol Pot.”

Mr. Koppe related how Phy Phum’s statement is “remarkably similar” to what his client has said all along.

He confirmed that other witnesses (who did not appear before the chamber) also confirmed this point. In particular, Heng Samrin denied that a kill policy against Khmer Republic officials or soldiers existed. As quoted from a book by Ben Kiernan, Heng Samrin recalled that they did not say “kill” but instead they said “scatter” the people of the old government. “Scatter them away; don’t allow them to stay within the framework,” Koppe reported Heng Samrin as saying. “It does not mean ‘smash.’ ‘Smash means ‘kill.’ But they used the general word, “scatter.’ Nuon Chea used this phrase.”

Mr. Koppe then reminded the bench that for two years the defense has consistently tried to gain the appearance of Heng Samrin (and other witnesses), “requests which have been consistently ignored or denied without reason.” He cited discrepancies with the interpretation of this testimony from the prosecution. “It is exactly because this dispute exists that Heng Samrin’s appearance at this trial is critical,” asserted Mr. Koppe, as would be other witnesses who have also been barred from testifying. If Heng Samrin is the only person who claims to know Nuon Chea’s intent is Heng Samrin, and the claim is reliable, “then it follows that his appearance at this trial is a non-negotiable, minimum requirement to Nuon Chea’s right to a fair trial.”

Not a fair trial

After reasserting the point that Nuon Chea’s trial cannot be considered fair in different words at least three times, Mr. Koppe wondered, further, about his overarching concerns about the validity of the whole tribunal process. “How far is this chamber willing to go to secure convictions against Nuon Chea in violation of the most basic rights to a fair trial?” he asked. He reminded the chamber that the international tribunal was constituted with a super-majority for the reason of avoiding this sort of situation. “This is where the rubber hits the road,” he asserted. “The situation is this, and the moment is now. If the integrity of these proceedings mean anything, the international judges of this chamber must now help.”

Even if it is a fair trial, Koppe asserts much of the evidence is not useable

Mr. Koppe then shrugged off the idea of an unfair trial, saying that even so, the evidence is insufficient to support a conviction. He went on to provide a detailed review of the evidence in the various matters for which his client is on trial, beginning with CPK policy of evacuations. He showed how there was no country-wide pattern of conduct, thus no centralized policy could be shown as having been established.

The prosecution would have the court believe, said Mr. Koppe, that the CPK ordered evacuation of cities and towns long before April 1975. He disputed the prosecution’s assertion that Lon Nol soldiers were executed (in just two of the evacuated cities, not all). He reported how evidence was gathered after the fact and was not firsthand evidence. For example, witnesses who claimed to see dead bodies could not prove that they were soldiers. In Mr. Heder’s report of what happened in Oudong, there were vague assertions that he “may have been told” about executed soldiers but denied seeing any himself.

Mr. Koppe stated, not for the only time today, that the evidence he was using to dispute the prosecution’s case was, in fact, evidence placed before the court by the prosecution, not the defense. At every opportunity during the morning’s delivery, Mr. Koppe pointed out to the court that his ability to turn evidence around in this manner was sufficient to call the evidence “irrelevant” and making it of “no probative value,” and that it should thus “be disregarded.”

Of prosecution evidence from eight sources regarding the evacuation of Kompong Chhnang, seven (according to Mr. Koppe) reported that Khmer Republic soldiers were not executed. The one remaining witness, reported Mr. Koppe, had only a “vague” recollection of hearing about deaths, but could not claim to be a direct witness, or to have seen dead bodies, or to have notes or recollections of who his sources were, or how those sources got their information, or even if those sources said it was Lon Nol soldiers who had been executed. Mr. Koppe asserted, therefore, that Lon Nol soldiers were not executed, after all, in Kompong Chhnang in 1973.

Mr. Koppe then reviewed evidence from a 1973 issue of Revolutionary Flag concerning classes to be abolished—in particular, the “special class types,” in which he said Khmer Republic soldiers and police, with Buddhist monks, Cham ethnic people, intellectuals, and other national minorities. “The co-prosecutors defeat their own point,” said Mr. Koppe, asserting that the Closing Order alleges Buddhist monks were never targeted to execution, and neither were national minorities or intellectuals, prior to 1977. Even David Chandler said so, according to Mr. Koppe, and “once again, the co-prosecutor’s own evidence supports our contention, not theirs. If Lon Nol were similar to the groups named, it follows that they were never subject to a policy of execution.

Regarding an assertion of Lon Nol executions at M-13 prior to 1975. Mr. Koppe said, “This just is not true.” He then provided a detailed explanation why this bit of testimony, too, is irrelevant. The total number of people executed at M-13 during the seven-year civil war was 200-300, but there is no proof they were Lon Nol soldiers. “Are these CPK senior leaders who allegedly executed 200 spies over a five year civil war the same indiscriminately murderous maniacs whom the co-prosecutors have described over the last week?” he said.

In fact, said Mr. Koppe, there are only two witness statements of actual executions between 1968 and 1975, and these, he contends, are “meager” and uncorroborated, although one witness said lower-level soldiers below the rank of major and civil service personnel were left unharmed. Anyway, these witnesses did not appear before the chamber and were not on the prosecution’s witness list. Mr. Koppe indicated that had the witnesses appeared, he would have liked to cross-examine them on the details of their weak assertions. But since cross-examination wasn’t possible, he asserted, the statements must be deemed irrelevant.

Mr. Koppe pointed out statements that the co-prosecutors chose not to mention, in which Lon Nol soldiers were forgiven and released prior to 1975. Otherwise the chamber, he said, should see prosecution allegations of CPK brutality “for what it is: An effort to distract the chamber from the absence of any actual evidence with vague and unrelated character assassination.” Mr. Koppe then offered an example from evidence the prosecution had characterized as “extremely important” but which Mr. Koppe found “absurd and unfounded” and a “fantastical claim” regarding the treatment of 3,000 Khmer communists returning from Hanoi.

Mr. Koppe pointed out statements that the co-prosecutors chose not to mention, in which Lon Nol soldiers were forgiven and released prior to 1975. Otherwise the chamber, he said, should see prosecution allegations of CPK brutality “for what it is: An effort to distract the chamber from the absence of any actual evidence with vague and unrelated character assassination.” Mr. Koppe then offered an example from evidence the prosecution had characterized as “extremely important” but which Mr. Koppe found “absurd and unfounded” and a “fantastical claim” regarding the treatment of 3,000 Khmer communists returning from Hanoi.

In summary of this portion of his statements, Mr. Koppe claimed that the evidence is clear that Lon Nol soldiers were not executed in the evacuated towns and cities prior to 1975, that the CPK grouped Lon Nol soldiers with other groups that were not executed prior to 1975 (or, in most cases, at all).

A look at the period relevant to the charges: April 1975 and beyond

The next key point Mr. Koppe addressed had to do with direct evidence of Nuon Chea’s intent to execute Lon Nol soldiers. In a phrase, there were “no probative documents.” Mr. Koppe cited inconsistencies in the testimony to support his assertion. He said that evidence of any actual executions in April 1975 was “exceptionally limited; not a single witness in two years personally witnessed the killing of a single soldier,” he said. In fact, Ben Kiernan’s interviews showed the release of hundreds of Khmer Republic soldiers in July 1975. Any other related evidence is from out-of-court witness statements which the defense has been unable to cross-examine, and who did not give firsthand accounts of Lon Nol soldier killings, only of soldier segregation. Disappearance did not necessarily lead to execution, or even arrest.

The evidence is no more than “distant hearsay,” said Mr. Koppe or, at best, instances of the death of a single person. He then showed contradictions in certain related testimony, which makes them “unreliable.

“And,” he added, “the facts that none of these witnesses appeared for cross-examination is of critical importance. This is not a mere technicality. I remind the chamber that it adopted an extremely low standard for the admission of these out-of-court statements into evidence. In our view, the chamber admitted the vast body of these statements far larger than any other international criminal trial in history. But the chamber, you, Mr. President, Your Honors, assured us that there was a sharp distinction between admissibility and probative value. This chamber assured us that statements admitted without cross-examination would be entitled to little or no weight.” Mr. Koppe held up the statements under current discussion as examples of statements of dispute between the prosecution and defense.

The unreliability of the evidence was revisited again, as was the denial of the request by the defense to cross-examine the witnesses.

An explanation of why (and when) Lon Nol soldiers were executed

Mr. Koppe spoke about the changed circumstances for Lon Nol soldiers beginning in 1977 and continuing into 1978. In 1977 troops from the southwest zone began to clash with those in the north and central zones. Soldiers from the southwest took over the north, and that was when Lon Nol executions began. Similarly, during the evacuation of Phnom Penh, soldiers captured some Lon Nol soldiers, but troops from other zones took those soldiers away. Evidence shows the four zone armies occupying Phnom Penh were “competing and antagonistic arms between which confrontations erupted,” according to Mr. Koppe. The picture is not what a centrally orchestrated system would look like, debunking prosecution assertions of party central control over the situation.

As for regions beyond Phnom Penh in those days, Mr. Koppe demonstrated that evidence from the co-prosecutors is “inconsistent” and “insufficient.” He spent time detailing this assertion as the 40+ people in the trial chamber looked on. Some statements were not made under oath and the defense was unable to cross-examine many witnesses; thus, he said, much or most of the evidence is of questionable probative value.

Mr. Koppe also pointed out evidence supporting the defense assertion that Lon Nol soldiers were not killed by the CPK. In one case, a witness, said Mr. Koppe, was hundreds of miles away from the events he purported to describe. It seemed a “reasonable conclusion” then (to Mr. Koppe) that Lon Nol soldiers were not executed in the east zone, the special zone, or the central zone.

As he spoke, the following statements continually cropped up as Mr. Koppe pursued a litany of examples in his detailed analysis debunking the prosecution’s assertions:

- “The evidence is manifestly irrelevant” or “inconsistent” or “conflicting” or “unreliable;”

- “The probative value is low;”

- “The evidence is not authenticated by testimony,” and;

- “Even if the evidence was reliable, it would support the defense, not the prosecution.”

In all, regarding the assertion by the prosecution of wide-spread executions nationally of Lon Nol soldiers, Mr. Koppe detailed the admitted evidence and found just 10 witness statements and two government reports, but noted they were limited in almost all case just to two zones and not necessarily to April 1975. “The critical point is that these last five statements say nothing at all that remotely resembles the kind of pattern that the prosecution says proves the centrally-directed nature of this supposed policy.” At this point Mr. Koppe revisited the testimony he just detailed. None, he asserted can begin to prove his client’s complicity in a pattern of execution. “Not a single one was consistent with their supposed pattern,” said Mr. Koppe. “Not even one witness described facts consistent with the pattern that the co-prosecutors say was so widespread and so universal that Nuon Chea’s responsibility is established beyond a reasonable doubt. They have failed completely in their attempts to do so.”

The supposed killings of Lon Nol soldiers in Phnom Penh itself

“This claim, too, is incorrect,” began Mr. Koppe as he introduced his new topic of discussion.

This claim was not established by the CPK’s execution of a small number of officials, those at the very top levels of the government, after the liberation of Phnom Penh. Those officials were detained, true, but Mr. Koppe questioned the reports of execution. Besides, he said, the “executions of such persons, even if it had occurred, would not be relevant or probative to anything to do with Toul Po Chrey or a general policy affecting Lon Not officials or soldiers.” And then Mr. Koppe went into minute detail to show the dangers of relying on OICJ statements, debunking one after the next. Witness testimony was hearsay, or irrelevant, or misguided, or unreliable. In one case a witness statement was actually a quote from a book. There is no way to know who some of the witnesses are or more details about their statements.

“They cannot now, for the very first time after six years, tell us this anonymous source, who may have given an interview to somebody under unknown circumstances single-handedly establishes that hundreds of top Lon Nol soldiers were executed in Phnom Penh,” said Mr. Koppe, continuing his theme of the day. “Mr. President, this is ridiculous and should be rejected out of hand.”

To finish the first portion of the morning, Mr. Koppe spoke about “other incomprehensible testimony” having to do with radio and other broadcasts in which only one person was found who could testify about them. He finished by accusing the prosecution of arbitrary selection of documents to support their allegations and seizing other manufactured impressions for the court to bolster their arguments.

A break of 20 minutes ensued.

More of the same

Afterwards, Mr. Koppe continued turning to the documentary evidence of the co-prosecutors, and to assert it proves nothing of any substance. For example:

- Documentary evidence relied on the prosecution regarding the existence of an alleged policy of executing Lon Nol soldiers: “systematically irrelevant and unreliable;”

- An executive order from July 1975 involving an order delivered to execute 17 people but not showing where it came from or to whom it was delivered;

- A policy questioned because it said to examine soldiers, but if a policy existed to execute all soldiers, suggested Mr. Koppe, there would be no need to examine them;

- Criticism by Mr. Koppe in the face of a May 1976 news report from French press of the prosecution’s continual reliance on news sources as an indication of on-going use of weak evidence, and;

- Other evidence is dismissed by the defense as “completely irrelevant.”

Mr. Koppe went into some detail regarding an assertion claimed by the co-prosecutors that Khmer Republic prisoners were executed at S-21. There is “not a shred of evidence that a single person was detained at S-21 because they were a former Lon Nol soldier,” said Mr. Koppe, who stated that only two percent of those at S-21 were formerly affiliated with the Khmer Republic, which, he added, disproves that Lon Nol soldiers were executed in general.

“In summary,” said Mr. Koppe, “the co-prosecutors are unable to show that anyone in the party center intended the execution of Lon Nol soldiers of any rank.” If a policy existed, it could only have been severely limited in time and scope, he said. No systematic pattern can be deduced from the evidence. No policy existed in April 1975, or before that. And what little evidence does exist concerns only high-level officers and top-ranked civil servants. “There is not a shred, not an ounce, of evidence that the CPK intended to execute ordinary soldiers or authorities.”

The timing of the alleged policy

Again, Mr. Koppe decried the timing of the alleged CPK policy, citing inconsistencies and a failure by the prosecution to articulate “any coherent theory of their case.” He said the evidence shows no policy could have gone into effect prior to April 1975, despite the prosecution arguing last week that such a policy existed long before April 1975. Mr. Koppe showed his point using Stephen Heder’s report of a chief military commander in the north zone, who claimed he would have known about a policy had one existed before May 1975.

Other alleged inconsistencies within the co-prosecutors’ position did not escape Mr. Koppe’s scrutiny. “They quote snippets of these statements, stringing them together as generalized support for an abstract concept which they call a policy to execute Lon Nol soldiers and officials,” said Mr. Koppe as he went on to reassert the same basic premise for some additional minutes.

Three crime-based elements regarding Tuol Po Chrey

Mr. Koppe’s opener regarding this new topic was a familiar refrain: The evidence is limited and inconsistent. There is “no physical evidence, no bodies of any victims, no names of any victims, no eyewitness testimony of killings, no eyewitness test of the transaction that led to the killings,” he asserted, all of which is “manifestly insufficient to support a conviction beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Second, he said, the chamber cannot conclude that his client is accountable for the events at Toul Po Chrey because evidence has shown that the CPK never adopted a policy of killing Lon Nol officials.

Finally, said Mr. Koppe, it is easy to see that lower-level, zone-based officials would have had far more substantial motives and opportunity to commit the crimes at Tuol Po Chrey. That is, if the chamber decides executions did in fact occur, the only reasonable conclusion would be that they happened without the knowledge or intent of party center.

Thus, according to Mr. Koppe, the reliability of information in the case files regarding Tuol Po Chrey is “crucial.” He wondered aloud if it is sufficient just to establish that the killings actually occurred. To assess the allegations, he reported, the OICJ did a site visit to the alleged site and carried out a thorough investigation. Their report detailed the findings. “And what were those findings, 30 years after the fact?” he asked. The report showed four items: fragments and debris of bones, two fired shell casings and one bullet, artifacts such as belt buckles and zippers, and fragments of cloth mixed into soil.

A light moment as Mr. Koppe slips up

At this point, the chamber, gallery and media room got some much-needed comic relief with a slip of Mr. Koppe’s tongue when he said, “The chamber is aware I am not a lawyer.” He quickly corrected himself: “I am not an investigator. But if I see shreds of cloth and belt buckles, I do not presume it is evidence of a 30 year old execution.”

He continued, saying, “Was no gravesite discovered? No. Sites observed, examined? No. Not a single corpse? No. Bone fragments tested? No. Fragments human? No. Without physical evidence of murder at Tuol Po Chrey, how can there be proof beyond a reasonable doubt of a murder?” Noting that the area was a former Lon Nol army camp, the investigators only concluded that it “could be” a possible crime site. “This is not enough,” claimed Mr. Koppe, who went on to attempt to debunk, at length, witness testimony regarding what happened at Tuol Po Chrey.

The witnesses’ testimony he said, “is neither compelling nor reliable.” The Nuon Chea defense team, he said, sought months ago to have the witnesses appear before the chamber where their allegations could have been questioned, but “despite the fact that Tuol Po Chrey is only one of three crime sites at issue, this chamber declined. Minimal fair trial guarantees require these statements be disregarded and assigned zero probative value,” declared Mr. Koppe. And regarding the three other witnesses who did appear in this matter, said Mr. Koppe, evidence was again unreliable, confused, inconsistent, and contradictory. Besides, witnesses shown in the video, “One Day At Toul Po Chrey by Rob Lamkin could not be located. This failure, maintained Mr. Koppe, “significantly reduces the probative value of the evidence.”

At this point, Mr. Koppe stated he would detour for a moment to highlight the quality of evidence in the case file regarding how death toll reports from the evacuation of Phnom Penh were determined. The principle estimate comes from Ben Kiernan; his method was to ask less than 100 individuals the number of family lost in the evacuation. These people reported the average loss of two relatives each. Kiernan then applied this to the population of Phnom Penh as a whole and deduced that 10,000 died during the evacuation. “Such calculations are grossly simplistic,” asserted Mr. Koppe. Other calculations were likewise unsubstantiated and misleading, and should be regarded actually “as gross miscalculations based on flawed evidence.”

Nuon Chea cannot be convicted, asserts Mr. Koppe

Anyway, he said, turning his attention back to Tuol Po Chrey, the evidence does not show that the reputed executions took place, at least not strongly enough to prove them beyond a reasonable doubt. The evidence as presented by the defense was, in Mr. Koppe’s opinion, sufficient to establish that Nuon Chea is not guilty of the crimes charged in connection with the events of Tuol Po Chrey, and may not be convicted. In fact, he suggested, Nuon Chea cannot be convicted anyhow. He then argued the point that co-prosecutor failure to specify the identity of those killed at Tuol Po Chrey beyond the generic phrase “members of the Khmer Republic” is “fatal to the argument.” He pointed out that the evidence proves unequivocally that the victims were overwhelmingly ordinary citizens and low-ranking soldiers.

Mr. Koppe wondered this: If Nuon Chea is not responsible for these crimes, then who is? “Nuon Chea had never heard of Tuol Po Chrey before this trial and does not know what happened there,” said Mr. Koppe, but he indicate that it was “possible for local cadres or the northwest zone secretary commanders to have the motive and opportunity to do so.” Mr. Koppe then took a short verbal detour to speak about opposition to Pol Pot and party center leaders which could have explained who was actually responsible for the events at Tuol Po Chrey. And yet, accused Mr. Koppe, in spite of all this evidence, the co-prosecutors persist in their belief in a simplistic, easy to follow story about Democratic Kampuchea that executions came about from orders from party center, with Nuon Chea being responsible. Mr. Koppe refuted this, however, with a quote from Ieng Sary, who said, “Even Pol Pot and Nuon Chea, when they were in So Phim’s zone, the East zone, they were afraid. I went with them once and knew that, and saw that…in that zone, if So Phim wanted to kill it was not necessary to ask upper echelon. The organization was like that: Each zone was independent, kill as you please, do as you please.”

“Mr. President,” concluded Mr. Koppe, “I think this excerpt speaks for itself. We submit that on any standard of proof it is apparent our client Nuon Chea is not criminally responsible for the events at Tuol Po Chrey. The co-prosecutors’ claim that they have established Nuon Chea’s responsibility beyond a reasonable doubt without any direct evidence is nothing short of absurd.”

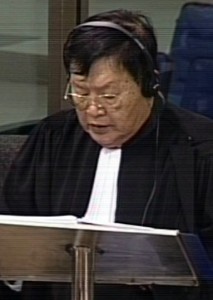

Mr. Koppe then yielded the floor, and the assembly departed for the lunchtime break. At 1:30 p.m., Son Arun, Co-Lawyer for Nuon Chea, stepped to the podium. He began by taking the co-prosecutors to task, saying they seem to have a “fundamental misunderstand how a criminal trial is supposed to work” and reminding them that “Nuon Chea is not required to explain why he did anything. The co-prosecutors are required to carry their burden to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Nuon Chea intentionally committed criminal acts.”

He also took the chamber to task for persistently refusing to allow the defense to call key related witnesses.

A re-summary of key historical points

Mr. Arun spent some time re-summarizing key historical points mentioned on Tuesday:

- How the CPK took power in 1975 facing the predicament that rice paddies and railways and roads had been subjected to widespread destruction from American bombing;

- How farmers were idle in the cities instead of tending to their farms;

- How Cambodia was (always had been) a peasant agricultural society, but (again) that a number of paddy fields were destroyed by the bombardment, and;

- How, under these circumstances, the CPK determined that Cambodia was incapable of supporting urban centers that produced nothing and at the same time maintained social and economic structures that perpetuated inequality.

That last conclusion, said Mr. Arun, was deeply connected to the CPK’s ideology and ideas of modes of production. He reiterated that it is impossible to view the evacuation as an isolated event and that the CPK’s plan did not end at the evacuees’ destination. The plan was part of their effort to establish agricultural cooperatives as the standard unit of the Cambodia economy.

And yet, said Mr. Arun, the co-prosecutors continue to contest Nuon Chea’s motives instead of considering what the concept of cooperatives meant to the CPK as politics or economics. The co-prosecution preferred to dismiss the actions of the CPK simplistically, as “enslavement.”

Mr. Arun then widened his comments to “reputable organizations such as the World Bank and the United Nations” saying that in 1975 even they supported involuntary population movement for projects (such as generating electricity) in many countries as “evidence of progress.”

Between 1955 and1990, indicated Mr. Arun in an apparent effort to justify the evacuation of Phnom Penh in 1975, “tens of millions of people in India, China and Africa were possibly displaced by dam, mine, and industrial construction, industrialization and other causes” often bankrolled (until the 1980s) by the World Bank and even by the UN.

Perhaps the forced evacuation was actually lawful

Mr. Arun accused the co-prosecutors of choosing not to consider whether the evacuation might have been lawful in light of the overwhelming state practice approving involving displacement in a wide variety of circumstances, or whether the establishment of cooperatives might have been part of a legitimate program. In April 1975, he said, Nuon Chea had good reason to believe cooperatives were an effective method of production, and he argued that it was impossible to adjudicate the evacuation of Phnom Penh without the implementation of cooperatives.

And yet, said Mr. Arun, the co-prosecutors “successfully opposed our request to add cooperatives to the scope of this trial, and thus prevented any substantive explanation of how cooperatives actually worked. Now, seven months later they come and tell us ‘you should reject his claim that the evacuation was part of a legitimate economic program.’ The hypocrisy is apparent.” And, asserted Mr. Arun, the chamber, having chosen to exclude these questions from the scope of this trial, must not base its conclusion about the legality of the evacuation on what took place in the cooperatives.

Mr. Arun disagreed with the co-prosecution’s allegation that the forced evacuation was an “inherently punitive act” against the population of Phnom Penh, or that the CPK was conducting itself maliciously for no obvious reason. He said the defense views such actions as further attempts to “reposition the CPK as a criminal entity, to strip it of its political objectives, to infuse the CPK with criminal intent, and to create a simplistic shortcut around the complicated and difficult questions of whether Nuon Chea intended to commit the criminal acts with which he is charged.”

Defense rejects validity of secondary sources

Mr. Arun reviewed the stance of the co-prosecutors that the CPK viewed citizens as enemies of the party, a claim supported by a long line of quotes from secondary sources. “We reject the use of this evidence from a long line of foreign academics who were not present in Democratic Kampuchea,” said Mr. Arun. “These people cannot possibly know what was in Nuon Chea’s mind.”

He recalled one witness who claimed he never received any instructions that 17 April people were considered enemies. Yet, asserted Mr. Arun, the co-prosecutors have continued to try to misrepresent this testimony and trick witnesses. That witness stood firm, correcting the prosecution, testifying, “We never treated anyone (including a baby) as an enemy because we had to liberate the cities. We never waged war with the civilians. Indeed we treated other opponents like the soldiers of the other party as our enemies, but we never treated civilians as our enemies.” The notion that city dwellers were the enemy of the party is refuted by a “veritable stockpile of evidence,” according to Mr. Arun. People testified that they were provided food and shelter by base people on their arrival at their destinations. Mr. Arun then revisited evidence already mentioned on Tuesday.

Although the co-prosecutors tried to say the testimony showed attitudes toward city dwellers, Mr. Arun accused them of relying only on evidence such as that of secondary references such as Philip Short.

Nuon Chea was not the Deputy Secretary of the Red Cross

Dire condition in 1975 led to the second forced transfer, or, as the defense refers to it, the second population movement. Although the prosecution tried to show that the motives of the CPK were “not humanitarian,” and that Nuon Chea’s explanation for the evacuation must be dishonest, Mr. Arun had a different take on the matter:

“Never once,” he said, “has [Nuon Chea] claimed it was a humanitarian act. He was not the Deputy Secretary of the Red Cross. He was the Deputy Secretary of the CPK. He was fighting a revolutionary war. He is not required to prove he was a humanitarian to justify his policies. The only relevant question is under the totality of the circumstances did the second evacuation of Phnom Penh constitute a crime against humanity.”

The point was, claimed Mr. Arun, that whether or not a food crisis existed, the population would likely have been moved into cooperatives anyhow. The decision was driven in part by that crisis, though, and the evacuation was driven by various factors. By that time, according to Arun, hundreds died each day of starvation in Phnom Penh. Either way, though, Nuon Chea genuinely believed that collectivization was essential to the production and delivery of rice, and that resettlement was in the best interest of the population. “It was a legitimate decision,” said Mr. Arun.

The next overarching topic for the defense concerned alleged crimes other than those committed during the evacuation. Soldiers were mostly well organized and knew their roles in the command structure. Mr. Arun chafed at the co-prosecution’s reliance on foreign journalists for their information, most of whom encountered CPK forces for only a few short hours, making their “observations about the discipline of the soldiers they saw utterly irrelevant to the command structures of the CPK army.”

There was a separate critically important point in Apr 1975, said Mr. Arun: evidence showed the soldiers who implemented the evacuation of Phnom Penh acted under the control of zone leaders, not the party center. Repeated testimony by the soldiers showed that during the evacuation of Phnom Penh the city was geographically divided into 4 quadrants: southwest, east, north, and the “special” zone. Segregation between zones was so strict they were not allowed to leave the space controlled by their units. There were turf wars between the zone armies. Heng Samrin as deputy commander of one division of the East army was very well placed to make these observations. For this reason, the defense asserted that his appearance before the chamber was critically important for the evidence he could have given had he testified.

Even if the evidence were reliable (“and it manifestly is not” said Arun), the evidence would show that commands came from zone leaders and not party center. “We submit that the prosecution conceded this critical point last Thursday,” said Arun, “as they must since no evidence to the contrary exists.” Arun went on to examine related allegations against Nuon Chea.

Assertions by the defense regarding the second population movement

Mr. Arun articulated the charges faced by his client (extermination, political and religious persecution and charges of other inhumane acts through enforced disappearance, forced transfers, and attacks against human dignity) and said, “These charges are unsubstantiated. They are unfounded.” He spent some time showing co-prosecutors’ evidence as “weak, unfounded, and misleading” and concluded that their evidence does not prove anything beyond a reasonable doubt.

Mr. Arun reminded the court of an earlier assertion that Nuon Chea never ordered the second population movement, and that he learned of it only after the zones had set it into play. The logic that if Nuon Chea claimed responsibility for the first forced movement that he would also admit to the second forced movement if he was responsible for.

“He has no reason to lie,” claimed Arun. “He does not admit it because he was not the one responsible for the second forced transfer.”

The defense addresses charges of extermination

Nuon Chea, said Mr. Arun, “cannot be found guilty of this charge, because there is no evidence, let alone beyond a reasonable doubt, that mass deaths occurred during the second population movement.” He cited that the prosecution has been unable to point to any direct evidence proving otherwise. “Their evidence is misleading. One witness buried one decomposing body and that does not come close to the occurrence of mass deaths in relation to the second evacuation.” Mr. Arun also cited other misrepresented testimony and read it in “proper context,” and he also alleged that certain evidence constituted hearsay and conjecture, and well as being “disingenuous.” He then went into some detail to support his assertions of dishonest and manipulative use of evidence by the co-prosecutors. Numerous witnesses testified that no deaths occurred, he said. CPK cadres took affirmative steps to care for evacuees when possible, and provided basic food and other necessities. “Their condition was stable. Physical health was normal,” he claimed. “This lack of support for the charge of extermination outweighs the evidence of the chamber.”

“In addition,” he said, “the co-prosecutors cannot point to intent by Nuon Chea to cause death on a massive scale.” Had conditions been calculated to bring large scale death, then such would have been reported, but, pointed out Mr. Arun, large scale death would have been at cross-purposes to populating the zones. Anyway, he asserted, there is no evidence that Nuon Chea or the Standing Committee designed the death of a large number of people. “Nuon Chea,” said Mr. Arun, “must be found not guilty and accordingly the chamber must acquit Nuon Chea.”

Assertions by the defense regarding deaths in the cooperatives

Allegations of deaths in the cooperatives after the end of the second population movement are not valid, said Mr. Arun, claiming them to be outside the scope of the second population movement. “The co-prosecutor attempt shows their desperate need to bolster the evidence of the second population movement,” said Mr. Arun, “but it is irrelevant to the charges at hand and the chamber should give it no weight.”

The defense addresses the charge of political persecution

New people and individuals of the former Khmer Republic were reportedly specifically targeted, except, said Mr. Arun, that the co-prosecutors misrepresented the evidence. “They attempt to draw another misleading conclusion,” he claimed, “that the people were all new people and that the transfer itself was an act against this population.” He then chastised the co-prosecutors for avoiding paying attention to witness statements stating that the second population movement was comprised of both base and new people.

After the 20 minute mid-afternoon break, Mr. Arun finished his comments on this charge. “The co-prosecutors cannot point to any witnesses with direct evidence that new people were being singled out or treated in a discriminatory manner by the CPK cadre. There is literally no evidence to prove their allegations.” One woman’s testimony is speculation about her husband’s death, a speculation untested by cross-examination, said Mr. Arun. “This one statement dos not comes close to establishing a policy of killing former Khmer Republic cadre members.”

After the 20 minute mid-afternoon break, Mr. Arun finished his comments on this charge. “The co-prosecutors cannot point to any witnesses with direct evidence that new people were being singled out or treated in a discriminatory manner by the CPK cadre. There is literally no evidence to prove their allegations.” One woman’s testimony is speculation about her husband’s death, a speculation untested by cross-examination, said Mr. Arun. “This one statement dos not comes close to establishing a policy of killing former Khmer Republic cadre members.”

Another item of evidence, he said, “is even more attenuated, based solely on hearsay and speculation.” After going into detail, he went on to say that, “neither witness supplies direct firsthand knowledge, neither provides evidence to establish that a pattern to target this group was established.” He went on to provide evidence that, in fact, “many” witnesses stated they were afforded basic necessities, and many said they were “happy to join the second movement.”

Of those who reported poor conditions and treatment, none, said Mr. Arun, asserted it was based on their affiliations to 17 April people or their affiliation to the Khmer Republic. “Neither the co-prosecutor or co-investigating judges have advanced a shred of evidence that anyone, including Nuon Chea, has acted with intent because of association with former Khmer Republic or new people; neither is there any evidence that Nuon Chea issued any order to inflict political persecution as presented by the co-prosecutor. A reasonable trial fact must include that the co-prosecutors have not concluded beyond a reasonable doubt that Nuon Chea is guilty of political persecution,” concluded Mr. Arun.

Assertions by the defense regarding religious persecution

Evidence showing religious persecution of Cham Muslims in relation to the alleged second population movement, said Mr. Arun, “wholly and completely fails to support this allegation.”

Evidence shows that people of the Cham Muslim minority were among those moved but “the only conclusion supported by the evidence is that the experience of the Cham was not unique,” said Mr. Aram. “All transferees experienced similar treatment regardless of religious affiliation.” Cham people were not singled out, treated in discriminatory fashion, or forced to endure worse conditions than other evacuees.

“Likewise, no evidence of policy or intent by the CPK has been produced, and as such,” said Mr. Aram, “the only available option for the chamber is a finding of not guilty.”

The defense addresses forced disappearances

Charges that Nuon Chea violated the principles of forced disappearance must likewise be dismissed, asserted Mr. Arun, since the co-prosecutors have presented no evidence that forced disappearances occurred. “They cannot produce a shred of evidence that this actually occurred during the second forced movement,” he said. “The word ‘disappearance’ is completely absent from their admissions.” Mr. Arun reviewed the statements of six witnesses in this regard in some details before pronouncing that, “There is no credible evidence that forced disappearances took place or that Nuon Chea was aware of a substantial likelihood that such disappearances would occur. No direct evidence exists of any probative conduct related to such a policy. With no evidence to suggest that forced disappearances occurred, the only avenue available to the chamber is an acquittal.”

Assertions by the defense regarding other inhumane acts and attacks against human dignity

To deprive a civilian population of adequate food, shelter, medical assistance and sanitary conditions resulting in physical suffering and injury could earn a charge of inhumane acts and attacks against human dignity, but in the opinion of the defense, testimony of witnesses was extremely varied. Conditions during the second population movement were admittedly “difficult,” said Mr. Arun. “But the co-prosecutor’s brief refuses to acknowledge statements by other witnesses who refute this claim.” Those statements report that conditions were decent and that the health of evacuees was normal, and that food and water, etc. was provided by CPK cadres. “The co-prosecutor brief dishonestly disregards them,” said Mr. Arun.

This significant variance proves that there was a reasonable doubt about how transferees experienced the second population movement. Indeed, me said, some suffered–but many did not. Additionally, Mr. Arun pointed out, no one piece of evidence established the intent of Nuon Chea or the CPK to inflict upon evacuees serious mental and physical suffering. No evidence presented proved beyond a reasonable doubt that conditions were such as to cause serious mental or physical suffering, or a serious attack to their human dignity. There was no evidence to support the material elements of Nuon Chea’s individual responsibility, and no direct evidence exists of a directive or agreement emanating from the party center or any evidence probative of such.

“With no evidence of such,” said Mr. Arun, “the chamber is left with no choice but to acquit Nuon Chea on this charge.”

The defense addresses the charge of other inhumane acts

Evidence supporting this final charge, too, was not satisfied, according to the defense, for reasons already articulated. In fact, said Mr. Arun, some people were happy and willing to move to the northwest zone (where there was food). “Accounts of whether the movements were forced are in doubt, and must result in dismissal of the forced transfer charge,” said Mr. Arun. “And even if forced, the co-prosecutor has failed to prove the claim of other inhumane acts.”

The alleged second phase population movement was not a single cohesive act, said Mr. Arun in conclusion. There was considerable variation on conditions. “Even if the movement was inhumane, the variability of the experiences show these decisions were done beyond the party center.”

“Accordingly,” he said one final time, “Nuon Chea cannot be held liable” for other inhumane acts due to the forced transfer.

The time at the conclusion of Mr. Arun’s litany of the charges and the defense team’s answers to them was 3:30 p.m. The 398 attendees in the gallery sighed with some relief when the defense for Khieu Samphan elected to forego starting their closing statement until tomorrow’s session. Closing statements for the defense team of Khieu Samphan has been allocated two days, commencing Friday, October 25, 2013 at 9:00 a.m.