Civil Party and Prosecution Lawyers Call for Conviction on Penultimate Day

Today, the civil parties and prosecution both made their rebuttals to the past four days of defense closing statements in a measured and straightforward manner. Lawyers for the civil parties took the first quarter of the day, speaking for one hour, ten minutes, as promised. In the gallery for the morning were 119 students, 43 foreigners or VIPs, 65 registered with the civil parties, and 208 villagers from Takeo.

It was a busy day filled with refuting numerous defense assertions by remembering and reviewing the abundant information that has been gathered in the four years of investigation and nearly two years of hearings underlying this trial.

Lyma Nguyen addresses the first series of concerns for the Civil Party

First to take the floor was Civil Party Co-Lawyer Lyma Nguyen. For forty minutes, she reviewed a variety of topics, beginning with the apparent contradiction in which Nuon Chea admits that he was a senior leader for the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and accepts moral responsibility for events during Democratic Kampuchea (DK), yet continues to deny legal responsibility for crimes committed pursuant to those policies. Without proof of legal responsibility, she said, his admission of moral responsibility “does not amount to much.” But, she pointed out, there is ample evidence of his legal responsibility, all of it heart wrenching, from the victims of those policies. ‘Those victims belonged to the state, which treated them as cogs, as chattel, to be worked and to be gotten rid of when it suited the regime. This state of affairs is correctly characterized as a slave state,” she said, pointing out Nuon Chea’s central role as Deputy Secretary of the CPK’s Standing Committee.

Ms. Nguyen went on to address the “Newspeak” language of the regime, painting it as Orwellian in its euphemistic manner of often standing for the opposite of what was actually meant. The purpose was to disguise the truth by representing lies as truth. For example, she said, the “liberation” of Phnom Penh really meant enslavement, and “evacuation” was not for the purpose (as it usually is) of moving people from a place of danger into a place of safety, but in 1976 CPK-speak, it meant a forced move to a place of danger for the people. Such language permeated Khmer Rouge activities, she asserted, and Nuon Chea Nuon Chea was the “Father of Newspeak.” He was personally in charge of propaganda and education. To him, “love of the nation” and “killing of the people” were synonymous, a life-death contradiction. For one to prosper, the other one must die. His victims understood perfectly what education and re-education meant, she said: Those who went for training never returned.

Ms. Nguyen noted that Nuon Chea’s defense agreed that the movement propagated the use of warlike metaphors, but asserted that the violent metaphorical language was used to justify Nuon Chea’s policies of violence against people he labeled enemies. She proceeded to give numerous examples, including reviewing testimony from Duch regarding the meaning of many CPK terms. She then said that the civil parties ask the judges to “put an end to the Newspeak and Black-White language. Until the truth is revealed for what it really was, there cannot be real justice.”

Regarding the deceptions played on the population to achieve the first forced transfer (evacuation of Phnom Penh), she called the threat of an imminent American bombing “a lie.” Also, in answer to Nuon Chea’s additional claim that it was “logical and reasonable” to try to save the population from famine since there were just six days of rice supplies in the city, Ms. Nguyen pointed out that the assertion came with, “No sources, no references. Just sweeping statements to excuse the mass crimes.”

Pointing fingers in blame

She continued by pointing out the tendency of Nuon Chea to try to blame others and claim to know nothing about what was going on in DK. He would like to blame Sihanouk, Lon Nol, the United States, Thailand, “and when that’s not enough he blames local leaders, his own people. In doing so he demonstrates a total lack of remorse and lack of insight into his criminality.” She said that his excuses and justifications could do nothing to exonerate his responsibility to this court. His policies were intentional, and aimed at total control of the population by whatever means were necessary. She asked Nuon Chea to answer whether he’d do it again in his comments on Thursday.

She continued by pointing out the tendency of Nuon Chea to try to blame others and claim to know nothing about what was going on in DK. He would like to blame Sihanouk, Lon Nol, the United States, Thailand, “and when that’s not enough he blames local leaders, his own people. In doing so he demonstrates a total lack of remorse and lack of insight into his criminality.” She said that his excuses and justifications could do nothing to exonerate his responsibility to this court. His policies were intentional, and aimed at total control of the population by whatever means were necessary. She asked Nuon Chea to answer whether he’d do it again in his comments on Thursday.

Also, in citing statements from Duch to support her assertions, Ms. Nguyen pointed out how Duch had no reason to lie, and nothing to gain. “As head of S-21 he had contemporaneous knowledge of the ins & outs of the regime. We ask you to find Duch a credible & reliable witness,” she said.

Next, Ms. Nguyen addressed Nuon Chea’s denial of intent to discriminate against New People. Here again, she said, one can notice Newspeak in Nuon Chea’s perception that any additional hardship they faced was because of their inexperience at farming. Never mind, she pointed out, the evidence provided by civil parties about working from 5am to 10pm daily, being exposed to the weather, not having adequate food, and being under constant surveillance by Angkar. Referring again to the forced, coercive nature of the situation and how people were threatened with death if they did not obey, she felt such was ample evidence of insults to human dignity to the extent that it was, in summary, “hell on earth.”

Discrimination began, she said, with identification: People were identified as “17 April” persons, those who “reaped the benefits of the efforts of the peasants.” She cited much evidence from the civil parties referring to an intention to eradicate entire social classes, such as the intellectuals. One witness said, “They were intentionally letting us die of hunger and it was carefully organized from A-Z.” The prejudicial effect was clear, said Ms. Nguyen.

Regarding the final death toll from the DK years, Ms. Nguyen agreed that everyone has disputed the final numbers. “How many deaths are necessary to meet the threshold for this crime?” she asked. Evidence is overwhelming that many people were killed, “and even the accused’s defense has claimed that one death is too many.” Bottom line: there is no need for a specific number, as long as the standards of the crime are held up.

Selective misuse of the trial statements alleged by Co-Lawyer for the Civil Party

In terms of how to view the second forced transfer, Ms. Nguyen pointed out the way the defense was selective and out of context in its use of witness statements. The example she held up was the defense assertion that people were “happy” to go. In fact, she asserted, they were tricked by pretext to go without resisting, such as when the “happy” woman, a mother of three, was more likely hoping her situation would be better elsewhere. Ms. Nguyen offered many other examples of selective use of witness statements by the defense, and ended by asking the bench to give due weight to civil party oral statements.

When referring to the events at Tuol Po Chrey and the policy to execute Khmer Republic officials, Ms. Nguyen again asserted that they, too, were targeted as enemies in a “systematic, uniform, and widespread manner” which was known to civil party witnesses. “They can tell you what they saw from where they stood,” she said as she asked the bench to consider the accumulation of evidence. “Your Honors can reasonably and logically infer that implementation was conducted in accordance with central policy instructions from party leaders.”

The final topic on Ms. Nguyen’s agenda was Nuon Chea’s apparent perception that he has not been afforded a presumption of innocence. (His victims weren’t either, she reminded the court.) She referred to the defense assertion that the trial cannot be fair because of the western influence on its various panels (civil party, prosecution, and the bench), and how by using Khmer Rouge logic they have argued that this is a trial against ideology. Such comments, she said, demonstrate a high degree of disrespect for this judicial process, and imply a bias that is reminiscent of KR discrimination. “Perhaps what Nuon Chea is saying is that no court has the capacity or independence or competence to try him. Perhaps he is saying he should not be tried at all,” she said. “But for the masses of victims this trial is about the end of impunity.”

Still, she pointed out, “the civil parties have waited nearly 40 years for justice. Even if there is a conviction, the victims are clearly not winners.” In a trial about the initial days of DK and how it changed Cambodia forever, it has been a chance to confront the human faces behind it. Although, as Ms. Nguyen pointed out, the best way to really know the intentions of Nuon Chea would be to hear directly from him, he has declined to be interrogated or cross-examined, waiting instead to have the last word tomorrow. Nonetheless, “Justice comes in many forms, and in a court of law the civil parties’ justice manifests as the right to be heard and believed, the right to have harm acknowledged and to have reparation for harms suffered.”

At 9:40a.m., Ms. Nguyen yielded the floor to her colleague, Moch Sovannary, Civil Party Co-Lawyer, who offered an ambitious agenda in addressing the civil parties’ rebuttal to the Khieu Samphan defense.

She began by addressing the way the Khieu Samphan defense team has repeatedly tried to have the chamber buy the story that Khieu Samphan was of good personality, serious and meticulous. “But what has been raised is not at all correct,” she said. “Mr. Clean” (as he was depicted earlier) was not at all what happened during the DK period. She proceeded to work through various assumptions about why he, as an intellectual, was spared when other intellectuals were targeted by the regime and how, if he was so meticulous, he could not have known what was happening. Also, how could someone like him achieve a leadership position if he wasn’t eligible, as the defense asserted. “What does this say?” she said. “He was an ally of Pol Pot, an ally of this regime. He wanted to be part of this ‘glorious’ regime.”

Ms. Sovannary spoke of the Khieu Samphan manipulation of civil party statements and his defense’s efforts to have them disregarded. She reminded the court that the chamber has already stated how, where civil party written statements prove certain matters, this evidence can be admissible without requiring witness presence to testify live, Many civil party statements, she asserted are of highly probative value regarding the existence of crimes, especially where it supports other testimony.

The different Philip Short testimonies and which ones to believe

Nonetheless, she observed, the defense for Khieu Samphan in its closing statements seemed to truncate and manipulate civil party statements. She gave several specific examples and then recommended that the chamber be cautious when analyzing the quotes and excerpts made by the defense for Khieu Samphan. She also pointed out contradictory accounts used by the defense. Regarding some testimony by Philip Short. The Khieu Samphan defense team both raised doubts about his testimony, saying that he was not qualified to be an expert witness—and also raised excerpts from his testimony. “So, which Short was he quoting,” asked Ms. Sovannary, “the testimony he found relevant? Or the testimony he found unreliable?”

Nonetheless, she observed, the defense for Khieu Samphan in its closing statements seemed to truncate and manipulate civil party statements. She gave several specific examples and then recommended that the chamber be cautious when analyzing the quotes and excerpts made by the defense for Khieu Samphan. She also pointed out contradictory accounts used by the defense. Regarding some testimony by Philip Short. The Khieu Samphan defense team both raised doubts about his testimony, saying that he was not qualified to be an expert witness—and also raised excerpts from his testimony. “So, which Short was he quoting,” asked Ms. Sovannary, “the testimony he found relevant? Or the testimony he found unreliable?”

She then referred to other inconsistencies in the Khieu Samphan defense. One witness deemed “confused” had been cross-examined by the defense in a way that led the bench to warn them no less than 13 times to stop asking leading, repetitive, and otherwise unhelpful questions. Another issue was the assertion that food shortages were the main reason for the first forced transfer, but, she pointed out, shortages were an issue throughout the regime. If they had sufficient reason to blame it on a food shortage, why did they have to lie about a bombardment? Why not just say the evacuation was because of the food shortage?

Ms. Sovannary also questioned the effort to define set dates for the second forced transfer. It didn’t matter, she said, when testimony by various civil parties showed that the evacuation was actually cumulative, that there was no set ending to each phase, and that they were moved over and over. And if evacuees seemed “happy” to return to their home villages, why were they not allowed to actually go to those same native villages?

To end her part in the day’s proceedings, Ms. Sovannary concluded that one main factor all leaders should consider as a priority in leading a nation are its people. “People should be taken care of by the government, not be the subjects of a war,” she said. As victims, the civil parties believe that after this historical trial, these questions can be answered, and that is the importance of their participation in these proceedings on crimes against humanity. “

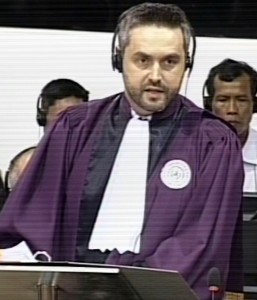

Nicolas Koumjian speaks for the prosecution

First to speak for the prosecution was International Co-Prosecutor Nicolas Koumjian, who held the floor from 10:10 a.m. until 11:20. Three more members of the prosecution team would follow him before the day was through. Senior assistant Prosecutor Keith Raynor would address the specific crimes being dealt with in Case 002/01. Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysack would speak to the issues regarding Nuon Chea. And Senior Assistant Prosecutor Tarik Abdulhak would address the issues related to Khieu Samphan.

First to speak for the prosecution was International Co-Prosecutor Nicolas Koumjian, who held the floor from 10:10 a.m. until 11:20. Three more members of the prosecution team would follow him before the day was through. Senior assistant Prosecutor Keith Raynor would address the specific crimes being dealt with in Case 002/01. Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysack would speak to the issues regarding Nuon Chea. And Senior Assistant Prosecutor Tarik Abdulhak would address the issues related to Khieu Samphan.

Mr. Koumjian focused largely on the legal requirements for a finding of involvement with a joint criminal enterprise (JCE) to be valid. First, though, he related the story of a woman who testified to losing 22 members of her family during the regime of the DK and how excited she was to be given the opportunity to speak, saying, “This is the day I have been waiting for more than 40 years.”

In her honor and for all those affected, Mr. Koumjian said, “That is all we ask on behalf of the co-prosecutors: That you judge this case fairly and justly in proportion to the gravity of the crimes. If the evidence did prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt, if we have shown you that the evidence is clear and convincing, and if the evidence of the crimes and the gravity of the crimes proves the accused’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, it justifies the sentence that was asked: life in prison.”

He proceeded to offer an eloquent defense of the fairness of the court and this trial, denying defense assertions that it is a propaganda exercise on behalf of the backers of this court. For example, he pointed out, Ieng Thirith was excused because she could not be given a fair trial. “Every effort is being made that this is a fair trial,” he said. The defense has had four days to put forth the allegation and arguments broadcast here and to the world, so this is not a propaganda exercise. The defense has had full opportunity to reply,” he said. “This is a trial about the truth. These accused are responsible for some of the gravest crimes in history.”

Mr. Koumjian asserted that the prosecution believes in the strength of the evidence, and that it justifies conviction. He pointed out how the defense “wants you to believe Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan are victims of an international conspiracy, but this is illogical and delusional. There is no need to discredit the Khmer Rouge; they are already discredited. They are inconsequential.”

Case 002/01 is not propaganda, and it is not a case about politics

He went on to deny defense assertions that the case is about politics or propaganda. Actually, he said, “It’s about historical crimes that happened a long time ago, but if international law means anything, then crimes of this gravity cannot be ignored.” He then accused the defense of arrogance in thinking they were capable in fulfilling their roles, but that prosecutors and judges could not understand their clients because they come from capitalist countries and former colonial powers. How interesting, he pointed out, that lawyers from those same legal traditions argued those points.

“It is an affront to international criminal law,” he said. Quoting from the Charles Taylor case, he repeated that “that conceit has no place in courts of law and no place in the judgment of this court.” The real issues he pointed to were how Khieu Samphan was the public face of the CPK regime, and that Nuon Chea was second in command. “So really, what we can agree on with the defense is that this trial is about the policies of CPK, DK, and the Khmer Rouge. Were those policies criminal? Or legitimate? Were they fulfilling ideological beliefs, or did their action amount to crimes? In our view the answer is clear: There was a campaign of crimes directed against the Cambodian people. Ideology is not the issue in this case.”

Mr. Koumjian also addressed modes of responsibility that took place. JCE is the mode of responsibility, he asserted, that best describes the conduct to be chosen by this trial chamber to judge. He went into some detail about the basics of JCE, and showed that the accused were aware of mistreatment. “In my view,” he said, “if you are aware, then you intend to further that system, so you have the intent for those crimes.”

How “intent” is different from “motive”

He differentiated the term “intent” from “motive” by saying that, “It is not necessary to show a person intended a crime in that it was the specific objective they sought, so long as they were aware that the consequence of their action would achieve that result. Case 002/01 showed that intent, he said in the first forced transfer. It involved many deaths of people Nuon Chea or Khieu Samphan would never know. Knowing someone specifically is not necessary when it is possible to show that they were aware of the consequences of that action. “When the crimes are obvious and ongoing, and the accused (especially those in high positions of responsibility) continue to participate in the system of mistreatment, it is in itself sufficient to convict them of these crimes,” said Mr. Koumjian.

When the morning break was done at 10:50 a.m., Mr. Koumjian continued by offering many examples of the evidence showing events in which the accused participated. One important example to the cadres was the broadcast of the threat to kill the seven “supertraitors.” This set an example that cadres everywhere would soon follow. Also, the “evacuation” of Phnom Penh “was an act that could only show to the cadres the complete indifference and hatred of the regime toward the people of the cities, people under suspicion of being potential enemies of the state,” said Mr. Koumjian. There were no exceptions. “Can you imagine elder persons such as Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea today being put on the streets to walk and fend for themselves, an act of clear inhumanity?” asked Mr. Koumjian. Only the regime mattered. “Individuals would be sacrificed.”

He cited that many or most of the troops entering Phnom Penh were teens, boys from rural villages, many uneducated, who followed the example that was set, and offered a Khmer proverb as an explanation: “The back foot follows the front foot.” The front foot was the top leadership, he said, including Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, who made it clear how the people should be treated.

And as for the defense’s assertion that week that Nuon Chea had a war to run, that he wasn’t head of the Red Cross, and so he didn’t have to worry about humanitarian concerns, Mr. Koumjian pointed out that the Geneva Convention would say otherwise. He went into considerable detail about the principles behind the international laws, and cited case history to underscore this point.

A JCE is shown by the contribution of the accused

One way a JCE distinguishes itself from other modes of participation is the contribution of the accused. This needs only be significant, said Mr. Koumjian and doesn’t even have to be part of the specific crime. The contribution only has to be to the enterprise. He reviewed the concept that if the accused shares intent, any significant contribution to the enterprise makes them responsible for all the crimes that fall into the JCE. In this case, a claim of forcible transfer can be found if the accused just provides trucks. Mr. Koumjian cited other case history to support his point. “These accused did make contributions to all the crimes relevant in 002/01,” said Mr. Koumjian

Then Mr. Koumjian turned the defense assertions to his advantage, saying that if the defense asserts that one accused says he’s “too intellectual” to contribute to the JCE, and the other says he’s “not intellectual enough” it doesn’t matter; the level of intellect does not contribute one way or another to accused contributions to these crimes, according to Mr. Koumjian. By this means, he attempted to show that the defense’s own arguments displayed the unique and substantial role each accused played in the enterprise. The closing order makes it clear that all the crimes charged were intended by the accused and all were within the JCE.

Regarding the defense’s mockery of the prosecution’s use of the word “enslavement”, Mr. Koumjian had some comments. In international law, he said, “enslavement has a precise meaning,” including ownership over another human and other deprivation of liberty. In the DK, “every aspect of life was controlled, down to whether they would live or die.” Yet, he said, the defense tried to say the word was an invention by the experts for the prosecution. He went on to cite descriptions by victims, slogans, and other information supporting the assertion that DK was a slave state—including an acknowledgement by Khieu Samphan himself that people on the cooperatives were not free. “Their idea of helping Cambodia did not include helping Cambodians. All the crimes in the indictment are part of the attitude best described as enslavement,” said Mr. Koumjian.

The work of demonstrating intent was found in the actions of the accused, mostly, but sometimes also, even when they choose their words carefully, through their expressed thoughts. Mr. Koumjian cited the long interviews Nuon Chea had with Teth Sombath in which he even said he had to weigh his words carefully. Asked about the killings, Nuon Chea said, “If we must choose one, I choose the nation. The individual, I cast aside.”

The point, regarding these two highly intelligent and very politically astute men is that their logic is continually troubling according to Mr. Koumjian. When pressed to explain to journalists about making children kill other children, for example, Mr. Koumjian cited reply by Khieu Samphan: “without Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia would have been in the hands of the Vietnamese, so they talk about little S-21 here to make people forget.” Indeed, the evidence shows a common JCE and all of the crimes charged were proven, charged Mr. Koumjian, as he handed over the podium at 11:20 a.m. to his colleague, Senior Assistant Prosecutor Keith Raynor.

Points of law or, the differences between evidence and assertions & suggestions

For the next 40 minutes, Mr. Raynor touched on crimes and policies of the accused, after starting by assessing some specific points of law. He wanted, he said, to differentiate between evidence that has been heard and assertions or suggestions that were made by the defense.

For the next 40 minutes, Mr. Raynor touched on crimes and policies of the accused, after starting by assessing some specific points of law. He wanted, he said, to differentiate between evidence that has been heard and assertions or suggestions that were made by the defense.

“Only the evidence matters. This is important because you have been bombarded with a raft of assertions and suggestions, especially by Nuon Chea’s defense,” he said, adding that, “You can disregard it from the outset.” He reviewed the applicable law on forced transfer and asserted that the prosecution has adequately proven seven features pertaining to it. He listed the first six of these, and said that the evidence supporting them is clear. Regarding the seventh point (that forced transfer can occur for the safety of civilian populations or for imperative military reasons), he said the prosecution has proved the evacuation of Phnom Penh took place without grounds permitted under international law. “These defense teams,” he said, “cannot as a matter of law rely on prohibited grounds.” At any rate, the forced transfers in DK were not humane or short lived, and there were no attempts to return victims to their homes. In fact, the party center announced that the steps they had taken were permanent.

Even if the judges were to want to go against decided international law regarding prohibited grounds, there are still questions they cannot answer: Did the situation in Phnom Penh justify forced transfer, really? What evidence has been heard to show that the accused acted on April 17, 1975 with an honest conviction that what they were doing was legally justifiable? (“There is no evidence,” said Mr. Raynor.) Nuon Chea has not testified and what his lawyer said in the closing statement is merely an assertion, not evidence. Thus the defense fails, because they cannot rely on permitted grounds despite the fact that Nuon Chea was trying to assert that it was his “economic policy.” Statements about the “monumental incompetence” of the regime were then made by the prosecutor, as well as some comments discounting the attempts of the defense to tie the actions of its clients to the policies of the World Bank and other external factors.

Maybe the “rogue” zone commanders are to blame

With reference to the second forced transfer, the prosecution underscored its contention, looking at the evidence, that it was centrally devised, despite the defense’s assertion that it was the rogue activity of zone commanders.

“This is a ludicrous assertion,” maintained Mr. Raynor, who then examined the claim by pointing out that a secret, rogue plan would be impossible, given that the railways were extensively and repeatedly used. He described the railway system as a “highly-organized operation” and noted that the transfers would have necessarily involved many people, including trained railway workers and a telecommunications network.

Proving murder without direct witnesses is not new

Mr. Raynor then spent time detailing how it is, in fact, possible to try a murder case without any direct witnesses. He had done this, he said, dozens of times. It simply requires looking to and connecting the other evidence. Yet the defense submitted the thesis that a conviction requires a witness to the murder.

Mr. Raynor demonstrated for the court the legal process of finding useable evidence in situations absent witnesses. “If it’s credible”, he said, you put it in your judicial backpack and you use it, especially if it corroborates other evidence.” In the case of Tuol Po Chrey, various items of evidence show: an order was given by the zone commander to kill Lon Nol forces; the location was Tuol Po Chrey; a meeting attended by senior officers of the Khmer Republic who are transported by truck to that meeting; the same trucks take them to Tuol Po Chrey; radio communication concerning the matter.

“So there are victims, an order, a location for the killing, and radio communication. This is reliable, credible hearsay,” said Mr. Raynor. Add to that the testimony of another witness who said the day after the killings he saw victims who were tied together in groups of 15-20, and that all of the bodies had gunshot wounds. Another said people were told their arms would be tied because they were meeting the prince. Another reported bodies at that location “bubbling like molten tarmac” a day or so afterwards. “On that testimony, you can convict because it is reliable evidence in its own right.”

In addition, that example is just one regarding underlying policy. “Our case is that Tuol Po Chrey is but one example of a whole policy,” said Mr. Raynor, pointing out several other items of evidence that he would also include without worry of admissibility, such as photographs (“a picture never lies”). He then spoke about other examples of underlying policy bolstered by specific, isolated examples. All this could satisfy the court beyond a reasonable doubt both that the deaths took place and, once it is determined that multiple killings happened around the country in very strikingly similar circumstances, that the Tuol Po Chrey situation was part of a central policy. When two or more pieces of evidence support each other, when there are patterns or similar factual evidence, it can considered probative, according to Keith Raynor, and when that pattern becomes evidence, it can be viewed as central policy.

As for Nuon Chea’s being in command or control, the evidence shows that he said if he’d known about what was happening, he would have investigated. That demonstrates evidence of command, said Mr. Raynor. That showed evidence of control. He supported this assertion with examples, including from Duch’s testimony of party policies as they related to interrogation and “smashing.” He also pointed out several witnesses to the massacres of Khmer Hanoi as further evidence of central policy dictating killings.

As for defense efforts to accuse the prosecution of misconstrual, Mr. Raynor gave examples from the record clarifying the claim. In one, he showed military commander Chhouk Rin saying that people in the city were regarded as enemies. And what about Prince Sihanouk (who, said Mr. Raynor, hasn’t appeared much in this trial? “Bear in mind Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea were contemplating killing the prince for the good of the country, for economic policy. This is more evidence of their intention,” he said.

In a literary aside, Mr. Raynor addressed defense assertions about the quality and qualifications of the prosecution and the bench the other day. He began with a reference to William Shakespeare’s King Lear, written more than 300 years ago, and the character known as “the fool.” He then mused whether:

…coming before this court and insulting everyone in sight is advocacy? It’s not where I come from. It’s not international standards, but when you come into the courtroom and insult you and your court, and insult my colleagues here and the general public, and insult the international press and the diplomats and the diplomats’ wives, please do not think this is advocacy. I will leave it for others to judge if this form of advocacy leaves only the speaker looking like the fool.

Neither I nor my colleagues have been backpackers on the river. We are here to do our job. We are here to prosecute. We do it vigorously. That is our job. The defense did not like it, and of course, that shows. But, Mr. President, please do not be fooled by a first class amateur that we at the office of the prosecutor are not professionals.

Chamber president Nonn spoke to this unleashing of pent-up sentiment by calling on all parties to remember that rebuttal statements should be made with respect to the other parties and with the Code of Ethics in mind. He cautioned lawyers to “make sure you use your words carefully in making your rebuttal, so that your statement does not intend to insult other parties. Preserve your dignity as a lawyer.”

Mr. Lysak goes to bat regarding issues from the Nuon Chea defense

Next up was Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak, whose was prepared to address the Nuon Chea defense. He turned first to the assertion that the prosecution’s narrative of the events of the DK area convenient and simplistic, relying, as it does, primarily on secondary sources from a Western perspective.

Next up was Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak, whose was prepared to address the Nuon Chea defense. He turned first to the assertion that the prosecution’s narrative of the events of the DK area convenient and simplistic, relying, as it does, primarily on secondary sources from a Western perspective.

“Let me remind everyone here of the breadth and diversity that has been put before the chamber,” he said, citing the records used, including 1,000 surviving records from the CPK from 1975-1979, documents such as Revolutionary Flag, circulars from party leaders, telegrams, minutes of meetings, district & commune level records, security, radio broadcasts and official statements of the DK government, hundreds of statements by the accused themselves, interviews and speeches from 1970s through their arrests. In addition, the co-prosecutor pointed to their use of witness statements from surviving victims and CPK cadres, interviews of refugees directly after the events and in the ensuing years and by Co-Investigating judges.

Maybe the defense teams are not happy about the submission of this evidence, he said, “but in war crimes of this scale it is never possible to bring into the courtroom every witness.” It is standard practice to use evidence as it has been heard in this trial. And in answer to the defense assertion that the prosecution is trying to limit this trial to a biased account of the DK, he pointed out that it was the prosecution (not the defense) who put in the case file and introduced as evidence the writings of authors favored by the defense, such as Vickery.

In addition, mentioned Mr. Lysak, when it was the defense’s turn to provide a list of documents for submission, they offered nothing to the court. “They refused. If they were not happy with the documents on the case file, or those proposed by the prosecution, they had the opportunity [to submit their own list],”he said, “and they chose not to do so.”

The defense also asserted that the prosecution was ignoring the historical period and events preceding April 17, 1975. “Nuon Chea says we are only looking at the body of the croc and not its head or tail,” said Mr. Lysak, and “Khieu Samphan says we viewed the historical context as some sort of sideshow.” However, he said, the prosecution’s closing trial brief begins with 40 pages addressing in detail the time period from the mid-50s to the evening of April 16 1975. “We agree,” he said, “this time period is critical to this case.” A group charged with crimes that began the morning of 17 April had to make plans well ahead of that. “They did not wake up at 7:00 a.m. on the 17 of April and decide to evacuate Phnom Penh. It stemmed from a strategy that began as far back to the 1960s,” he said. “The head of the crocodile has been exposed.”

With respect to the second forced transfer, Mr. Lysak noted important admissions by Nuon Chea that the population would have been moved whether or not a food crisis existed. He related this to subsequent transfers, asking whether the defense could justify the forced transfer of the entire urban population of Cambodia to implement an economic policy. “The answer, under international law, is clearly no,” maintained Mr. Lysak, which makes Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan criminally responsible for the deaths that ensued as a result of these decisions. And when Nuon Chea admits he participated in and agreed with the first transfer and considered the second forced transfer a continuation of it, he bears responsibility regardless of whether he knew of all the details.

Mr. Lysak addressed the charge of extermination as it applies to the second forced transfer, in which the leaders made a knowing decision to send people into a zone they knew did not have enough food to feed the people already living there. (No wonder the Khieu Samphan defense did not want to hear what happened after those people arrived.) If you can look at the consequences of this second forced transfer, it is confusing when the accused say there is no evidence of death on a massive scale. Mr. Lysak referred to evidence (a contemporaneous report from the regime from Sector 5 of the NW Zone) that showed interesting information about the fate of the people. He read one that reported that 70,000 new people were moved into one district, with a CPK cadre description that said “it was the worst place of starvation and 20,000 people died in1976 alone.” Mr. Lysak said, “That, Your Honors, is death on a massive scale.”

The Nuon Chea defense contested the existence of the alleged policy of targeting Lon Nol officials and the events of Tuol Po Chrey. Mr. Lysak referred in particular to the” eloquently delivered thesis” by Mr. Koppe on Monday that reports of such killings around the country did not prove anything. However, this is exactly the principal basis of proof that Nuon Chea is criminally responsible (as part of the proof of the JCE), Mr. Lysak clarified, citing policies communicated by such sources as Revolutionary Flag.

Refute, refute, and refute some more the defense assertions

When Mr. Koppe also theorized that the executions of Khmer Republic soldiers and officials were concentrated in a few zones and thus did not represent a nationwide policy, Mr. Lysak refuted the assertion, arguing with numerous references that Lon Nol officials weren’t evenly spread out for various reasons. “The entire thesis of the defense was based on a flawed premise,” said Mr. Lysak, “but it doesn’t mean there wasn’t a common policy.”

There followed a presentation regarding the relationship between the CPK leaders in Phnom Penh and the Northwest zone, particularly commander and Zone secretary Ros Nhim (accused by the defense as being devious and harsh) who was reportedly autonomous. This assertion was set aside by Lysak with multiple references to evidence to the contrary. In fact, he said, Khieu Samphan himself explained how party center exercised its authority over the NW zone and that as early as 1967, Nuon Chea and party center had control over the NW cadres.

“The difference between the prosecution and the defense,” said Lysak, “is that we ask you to rely on the evidence, and they ask you to reach your conclusions based on the fact that some soldiers did not wear shoes.” The zone armies were part of a centrally-based command structure as of 1975, he reiterated. They were not autonomous, and did not act without direct orders from Angkar. In fact, at one point, Nuon Chea learned from Nhim of the execution of his own uncle Siv Heng and nephew; would Mr. Nhim tell Nuon Chea of the execution of his own relatives and yet withhold information about other executions? All evidence, according to Mr. Lysak, points to the fact that CPK leaders were well aware of the news, and they monitored it closely. There was much reference to evidence in which the zone leaders asked party center for orders. They did not act autonomously.

After the mid-afternoon break, the afternoon crowd of approximately 345 persons re-entered the gallery for the conclusion of the day of rebuttals. Mr. Lysak needed just a few minutes more to address issues raised by Co-Lawyer for Nuon Chea, Son Arun, in his closing statements. Mr. Arun had accused the prosecution of overstating the importance of confessions from S-21, saying Nuon Chea had access only to a small percentage of them. However, the statistical analysis of the defense, said Mr. Lysak, is the true distortion, and the truth was that Nuon Chea got many confessions from S-21. In fact, when asked by Thet Sambath, Nuon Chea said, “I didn’t read all the documents because there were so many.”

The reason this is relevant to judgment, said Mr. Lysak, is because the defendant is correct for purposes of the judgment; Nuon Chea does not need have to show complete responsibility for S-21, but simply that he participated in or contributed in the CPK plan to smash enemies of the party. “Whether he got 1 or 10 or 25, or 200, it proves his involvement in the JCE through which enemies were identified and killed,” said Mr. Lysak. Although in his interviews with Thet Sambath Nuon Chea never acknowledged responsibility for S-21, Mr. Lysak ended by referring the judges to chapter seven of Sambath’s book, which is “full of statements proving his involvement with S-21 and all that went on there.” After quoting from the book, he said, “Your Honors, I simply ask you to look at all the evidence together. We’ve been through it many times in this trial and it is our submission beyond a reasonable doubt that Nuon Chea was at the very heart of the CPK plan to smash persons identified as enemies of the party.”

The final task: refuting the defense for Khieu Samphan’s closing statements

To finish the penultimate day of this long and complicated trial, Senior Assistant Prosecutor Tarik Abdulhak stepped forward for the final hour. His tasks: address evidence pertaining to Khieu Samphan and his criminal responsibilities, and as a procedural issue, look at related issues on the scope of trial just addressed by Mr. Lysak.

To finish the penultimate day of this long and complicated trial, Senior Assistant Prosecutor Tarik Abdulhak stepped forward for the final hour. His tasks: address evidence pertaining to Khieu Samphan and his criminal responsibilities, and as a procedural issue, look at related issues on the scope of trial just addressed by Mr. Lysak.

Mr. Abdulhak posited that there are two additional reasons why the evidence is directly relevant; he cited precedent for the accusation of crimes against humanity from the case files at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) finding that contextual elements have to be proved and can go well beyond events for which accused are charged.

By definition, forced transfers are continuing crimes, a “series of purported justifications” for the evacuation of Phnom Penh and subsequent transfers. Under international law, the defense is tasked with showing reasons for the transfer, and once the problems leading to it cease, that permission is granted to the population to return. “So it stands to reason that the actions of the accused, in preventing evacuees from returning, are directly related to elements of the forced transfer,” said Mr. Abdulhak, who once again cited ICTY findings.

He also addressed Khieu Samphan’s criminal responsibility, and his role in “this vast JCE.” Of all the “far-fetched submissions from the defense,” he began, “perhaps the most far-fetched was that not only was Khieu Samphan not a leader, not only was he not involved in the crimes for the JCE, but he didn’t even qualify to be a person in the leadership of the party. Why? Because he was an intellectual.” Mr. Abdulhak went on to discuss this “complete lack of logical basis.” Khieu Samphan wasn’t the only educated person in the party (and here Mr. Abdulhak listed Son Sen. Ieng Sary, Nuon Chea, and others). He went on to list Khieu Samphan’s pre-1975 resume, including an admitted role with the coalition forces in conflict with the Khmer Republic, which made Khieu Samphan the highest-ranking communist in the FUNK and the GRUNK. He even admitted that he was “the only one” who could have established that coalition with the prince. He went on to revisit KS’s activities and use of violence, which was necessary as a member of the CPK because the goals were shared, and according to the Khmer Rouge could only be obtained through violence.

Khieu Samphan was the face of the Khmer Rouge, the man who, in 1972, called on the city to eliminate the traitors and others and their subordinates, in 1973 celebrated the destruction of 10 strategic villages and the smashing of 10,245 enemy heads, and otherwise made public calls for violence and killing, according to Mr. Abdulhak. When Udong fell in March 1974, Khieu Samphan announced it. From evidence that the Khmer Rouge executed captured soldiers in that period, Khieu Samphan was there endorsing the killings. If Ms. Guisse argued that evidence of meeting at B5 is not credible, said Mr. Abdulhak, “We strongly disagree. The witness was consistent, showed clear memory, and was found by us and Philip Short as highly credible.” And so on, through a litany of specific references to the evidence. Khieu Samphan planned unlawful acts. He was present. He participated, the prosecution argued.

And yet, according to Mr. Abdulhak, Khieu Samphan says he did not know, had no idea there was a plan to evacuate Phnom Penh. This is, said Mr. Abdulhak, “a clearly dishonest and disingenuous statement he had chosen not to have tested and was thus not entitled to probative value”.”

Mr. Abdulhak summarized Khieu Samphan’s first opportunity to address the people who were dispossessed and quoted him as saying on April 22, 1975, “This is our nation and people’s greatest historic victory.” He was celebrating how they drained the “enemy” of all strength and how the enemy died in agony. Khieu Samphan continues to insist (for example, in his July 1982 interview with the NY Times, when he said “equivocally and without reservation” that the evacuation of Phnom Penh was a collective decision, a decision in which he participated. The defense excused this, because they claim it was a “political” statement and had to be said to show loyalty.

“Do not be misled,” cautions Mr. Abdulhak.

In the evidence, Khieu Samphan asserted starting in 1982 that had a single person raised concerns to the group, the evacuation would have been called off. Is this consistent?” wonders Mr. Abdulhak, with the 1982 statement that it was a collective decision.

The real truth about who was in charge at the Ministry of Commerce

Next, he examined the positions and roles held by Khieu Samphan in the Ministry of Commerce – the material is “voluminous,” according to Mr. Abdulhak, but “relevant because by supervising the warehouses he was contributing to a JCE to move people into inhumane lives to produce rice and further the goals of the regime. Khieu Samphan would receive vast amounts of produce from various zones, including millions of kilograms of rice from the NW zone. Although the party line was to try to pawn Khieu Samphan off in his role in commerce as some sort of technical assistant, “They could not be further from the truth,” said Mr. Abdulhak. “This man was the party center’s man when it came to running a slave state on a daily basis.” Mr. Abdulhak detailed evidence and findings that placed Khieu Samphan no more than 300 meters from K1 and the rest of those in power while he was left in charge of exporting products and goods.

According to Mr. Abdulhak, evidence shows Khieu Samphan and Vorn Vet as the actual upper echelon at the Ministry of Commerce. “They supervised it, had power to direct it, and the ministry had no power to do anything without their approval.” Anyone with a report to submit at the Ministry of Commerce communicated with Khieu Samphan as the representative to Angkar, according to Mr. Abdulhak.

Khieu Samphan’s part in the party center is discussed in the briefs, said Mr. Abdulhak. He attended 86% of the meetings, he lived and worked with Nuon Chea and Pol Pot, took part in self-criticism sessions, ate together, worked together. Only Pol Pot and Nuon Chea attended more meetings of the Standing Committee. “He was very much in the heart of power. He was, with those leaders in Phnom Penh, in charge,” said Mr. Abdulhak. Evidence of his authority, power, and position is abundant, and even extended to being able to have a relative released from prison in Siem Reap.

Broadly, there is evidence that Khieu Samphan issued the order to kill the seven super-traitors. There is evidence he was a member of the Central Committee when the right to smash enemies was decided. Mr. Abdulhak named a long list of transgressions by Khieu Samphan over time regarding smashing and eliminating enemies. He played his part in denying DK atrocities (another contribution to this criminal plan). All evidence raised, said Mr. Abdulhak, shows a “continuing, unreserved, active and committed participation by this accused in the JCE which led to the crimes with which he is now charged. He was one of the most trusted people working with Nuon Chea and Pol Pot. You must not believe his assertions that he did not know and did not participate. They are bare lies,” said Mr. Abdulhak.

“At the end of this long, complex trial,” said Mr. Abdulhak in conclusion, “Go back to 17 April, 1975. This was a day which could have been a day of reconciliation, a day of hope. It could have marked the end of the suffering of the Cambodian people. The Khmer Rouge prevailed in the war, and their adversary surrendered.”

But it wasn’t to be, said Mr. Abdulhak. There was no room for reconciliation or compassion. “Instead of accepting the offer of reconciliation, they set out to destroy an entire way of life and turn a country into a suffering nation of slaves. These accused appointed themselves the masters of every life in this country, took it upon themselves to decide who lived and who died. They brought this country to its knees.”

They used a “veil of secrecy for the rules they implemented. But the veil has been lifted by the evidence before you,” he continued. “They are guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, and the sentence they deserve is a sentence of life imprisonment. Nothing can ever come close to matching the gravity of the crimes they are guilty of. We ask you to judge them fairly and find them guilty, and sentence them to life imprisonment.”

With that, precisely at 4:00 p.m., the prosecution rested.

A bit of aftermath

Chamber president Nonn consulted with the defense teams to arrange the agenda for the final day before the judges adjourn to deliberate the trial findings. On Thursday, October 31, both Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea will speak, at last, to the court and to the world. Each has been allocated two hours’ time. Since Nuon Chea wishes to speak for 1-1/2 hours or more, his team suggested to President Nonn that he might require a break in the middle. For the part of Khieu Samphan, his counsel may not need the full two hours allotted, and wishes any leftover time be allocated to Nuon Chea.

The proceedings were adjourned, and will resume Thursday, October 31, 2013 at 9:00 a.m.