“Oh My Budda…We Had No Breakfast after 1975”

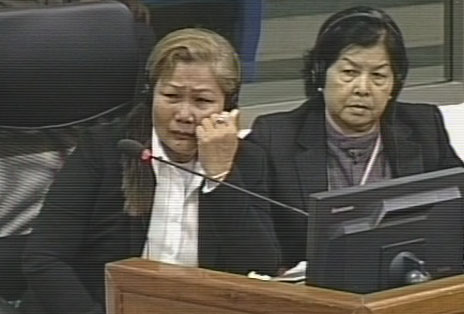

Today the court continued hearing the emotional testimony of civil party Hun Sethany.

This court is the first ad hoc tribunal to provide victims the opportunity to participate directly in the trial proceedings as Civil Parties. 1

Moch Sovannary, Civil Party Co-Lawyer, continued her examination started the day before, which you can read here.

Children

Ms. Hun explained that the children (ages 13-19) in Mobile Unit 2 were instructed to do the same works as adults. And, “they were given the same ration,” she said. The Khmer Rouge “did not care that they were children. They did not consider their young age or their weak strength. They did not have any sympathy for those children.” She testified: “Their health conditions deteriorated dramatically, though they tried their best to do the work. When they fell sick, no one came to visit them.

Working Conditions

Hun Sethany described that (during her time at the 1st January Dam worksite), she worked in three different locations: initially at the Trapaing Chrey Pagoda, then near the national road and finally near the river. The conditions were terrible and food t was insufficient, but “we had to work as we were instructed or we would not survive.”

Ms. Hun reiterated the point and started sobbing while she said it, wiping her eyes with a tissue:

“If we didn’t try our best to work, we would not survive. As a result of overwork at that site, I still have back pain today. What I did at that time was to survive.”

She went on to outline the brutal working hours. They would wake up by a whistle at 4:00 a.m. to start work by 5:00 a.m. They stopped at 11:00 a.m. for a two-hour lunch break. Work resumed at 1:00 p.m. and continued until 5:00 p.m. After a one-hour break, they worked from 6:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. The schedule would repeat starting at 4:00 a.m. the next day.

“On some days, when I was so tired,” Hun Sethany recalled, “I didn’t care about taking a bath. I slept in my working clothes. And in the morning, I didn’t care about changing I just kept working.” Every day she heard through the speakers that they had to work very hard. As she wiped the tears from her face, she demanded: “How come we were treated so inhumanely?”

Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak asked if she was given breakfast at the start of her work day.

“Oh my Budda,” she exclaimed, “we did not have breakfasts for ourselves. We were empty in our stomach. We were so hungry. No meals for us in the morning. If there was cold rice made by the cook, we would go there and secretly pick (sic) rice. Again, no breakfast at all; we had no breakfast after 1975.”

Ms. Hun told Ms. Sovannary that:

“In terms of the food ration there’s not much to say. You can imagine how many flies there were. You could hear them as if they were bees. Every ladle of soup that was placed into a bowl contained many flies, and we just had to pick the flies one by one out of the soup bowl. And we had to eat whatever was in the bowl.”

There were so many flies because there was no sanitation. Workers relieved themselves wherever they could. “I could not describe enough the awful conditions of the work site in terms of sanitation,” she added.

“Did anyone become sick?” Ms. Moch prompted.

“There was a base person from my village who died from overwork. He was unmarried and he did anything he was assigned to do. He would manually break rock and as a result he died,” Ms. Hun reported.

There were no funeral arrangements for this man. Hun Sethany recounted that “only us (sic) who knew him would quietly weep. We felt pity for him that he sacrificed everything for Angkar and at the end he died, and nobody cared that he died.”

Clothes

Ms. Hun told the court that, when she arrived, she was given a piece of cloth to make trousers and a shirt. (The workers only had one set of clothes that they wore every day). The sarongs that the women had were mended with patches. They could only wash them in river water. There was no soap, but, if they were considered to be too clean, they would be criticized, “accused of being from the upper class.”

“And as for women, we had periods…” she stammered and started sobbing again, wiping her tears and covering her mouth while she continued: “Sometimes our trousers were wet while we were working. We had no sanitary pads. When we saw that someone was having a period, we told them to go to the river to clean themselves using the water from the river.”

The Khmer Rouge “did not know the difficulty of the female situation,” she said, “and when we were working away from the river, we had to carry earth with the stain of the period on our trousers. And as you may be aware, it sometimes would come in large amounts. “

Filming at the dam site

Hun Sethany corroborated the video evidence that the court viewed yesterday on the 1st January Dam (and included in yesterday’s post which can be viewed here). She was working while the film was being shot. Further to the Khmer Rouge slogan of the day, the workers had been instructed to work “actively,” that is, to work extra hard and as fast as they could:

“There were announcements to encourage us to work even harder. There was a pole and the camera was attached to that pole. Everyone was told to work as quickly as possible and work as hard as we could….We were working very hard on that day… I heard screams and shouts from the unit chiefs to work harder. “

Murder of her father

Hun Sethany’s father was allegedly killed at the Wat Baray Choan Dek Pagoda next to the 1st January Dam worksite. Militia took him away:

“My two younger siblings came and told me that my father had been taken away and killed. He did not return. I told them that they had to try to work. We could not weep, because we were shocked. We had now lost our father. We had no time to pay our gratitude to our father and now he was gone.”

Mr. Lysak pressed her on how her siblings knew that their father had been taken to Wat Baray Choan Dek Pagoda. Ms. Hun was clear that everybody knew that the detention and execution site was at Wat Baray Choan Dek Pagoda.

When her father was murdered, she “could not cry and weep before other people because (she) was afraid that (she) would be accused (of being) psychologically sick.”

“I wanted to die in the period. I was very painful all over my body and my mind. I had to bear the situation. Only when there was heavy rain could I relieve myself by screaming and shouting in the heavy rain.”

Her father had been a teacher at Preah Sihanouk College, Kampong Cham province, during the Lon Nol regime. He had not supported the Khmer Rouge “at all.” Her “father was really terrified and afraid of communism … (as)they could kill anyone they wanted,” she said. She did not know why he was killed. He was told he was being taken to carry locks. Ms. Hun later saw many pits and graves in the Wat Baray Choan Dek Pagoda.

Cross-Examination

Victor Koppe, International Co-Lawyer for Nuon Chea, focused the cross-examination of the civil party back on the work schedule.

Hun Sethany confirmed all the workers were on the same schedule: “when we reached our workplace, we started working. No one was standing idle.” Challenged by the counsel’s reading in of a statement from Pech Sokha, a prior witness who had deposed that everyone started work at 7:00 a.m., Ms. Hun stood firm: “It is not correct. We would start work before the day broke.” Similarly, it was “not (her) experience” to resume work at 2:00 p.m. as had Mr. Pech. Under the lawyer’s encouragement, the witness did clarify that there was a short break at 9:00 or 9:30 a.m.

When Mr. Koppe tried to have Ms. Hun confirm that the work day actually was from 7:00 a.m. to 6:15 p.m., as three prior witnesses had testified, Mr. Lysak objected on the grounds that his colleague was being misleading in his characterization of the evidence of the three other witnesses. The Assistant Prosecutor noted that the men’s testimony differed as they were “perpetrators or senior cadres. He also requested that the prior testimony be referenced as per the rules of the court.

Mr. Koppe retorted that the objection was “very poorly formulated” for terming the former witnesses “perpetrators.” Judge Fenz directed the defense counsel to give the appropriate references.

Mr. Lysak rose again to argue that Mr. Koppe cannot “lead or mislead the witness” by attempting to represent that all three witnesses had agreed with the statement that work had started at 7:00 a.m. Mr. Koppe defended on the basis that Or Ho had agreed with Pech Sokha, but that, in any event, he would move on as he did not want to waste any more time.

As she had had a watch, Ms. Hun knew the first whistle had been at 3:00 a.m. The cadres could go to work later. She conceded that work started at 6:00 a.m.

“I heard what I wanted to hear,” concluded Victor Koppe.

Victim’s Impact Statement

Hun Sethany’s chose to make a closing statement about how she suffered from the crimes inflicted on her during Democratic Kampuchea.

Hun Sotheny went from living “a happy life with family” to losing everything: her parents and her siblings; her house and belongings; all her property. She now lives alone and is “so lonely.” She feels only others as “lonely as (she)… understand [her] situation.” Ms. Hun wants to know why she had to “suffer much in (her) life,” to go through “this bad experience;” why she had to suffer from having no rights or freedoms during the Khmer Rouge; and why the Khmer people had “the difficulty… (they) experienced.” She is still “so terrified,” and suffers from PTSD and trauma. But, she is “trying (her) best to live (her) life in the moment.”

Ms. Hun emphasized that she did not want a recurrence of the regime that killed hard-working, innocent people “because of words that came out of their mouths;” who would take someone away for any wrong doing; who separated families and persecuted the people. She beseeched the court: “If you realize what happened in that period, please do not let such thing happen again in this society.”

Ms. Hun closed with questions addressed to Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea:

- Are you responsible for the killing of human beings?

- Do you recognize and admit your mistakes?

- Do you admit your acts in that period?”

The President explained to her that, although Civil Parties are allowed to ask questions of the two accused, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan are exercising their right to remain silent.

You can watch her impact statement here. It starts at 21:11, with an introduction from the President of the Chamber, Judge Nil Nonn.

On behalf of the Chamber, Judge Nil Nonn thanked Ms. Hun for her testimony and for sharing her suffering during the Khmer Rouge regime. He wished her a safe journey home.

1. For further reading on Civil Parties, what this means and why it matters, see a good overview here. See this document prepared by the current International Civil Party Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud and this law review article in the Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights.