Wife Of Second-Bloodiest Cadre Testifies; Her Memory Fails

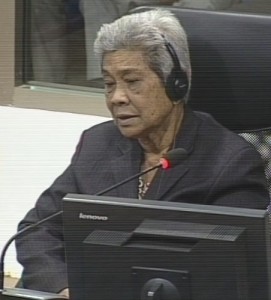

Witness Ms. Sou Soeurn (ស៊ូសឿន), wife of Ke Pauk. June 4, 2015. (Photo courtesy of Kim Sovanndany from DC-Cam)

For the closing witness on the January 1st Dam Site[1], the Trial Chamber heard the riveting testimony of Ms. Sou Soeurn (ស៊ូសឿន), wife of Ke Pauk[2], which ran for two days.

Ke Pauk was the Central Zone Leader (formerly the North Zone) who, according to Craig Etcheson, “next to Mok [the butcher], he [Ke Pauk] is probably the single bloodiest of them all.”

Ke Pauk, (photo by Tom Fawthrop via the Phnom Penh Post, here).

Ben Kiernan, in his obituary for the Guardian says: “Pauk became party secretary of the northern zone. He executed Thuon’s loyalists and appointed 10 of his own relatives to key positions. When popular revolt broke out in 1977, Pauk had hundreds massacred . . . In May 1978, in concert with Mok’s forces and Pol Pot’s centre units, Pauk’s northern troops began slaughtering the suspect eastern zone administration and population. In the largest mass murder in Cambodian history, they murdered more than 100,000 easterners in late 1978.”

__

Madame witness Ms. Sou Soeurn, wife of Ke Pauk, 79, took her oath before the Iron God (detailed in the last post here) and, together, with a Transcultural Psychosocial Organisation Cambodia (TPO) representative[3], took the stand.

She headed the district committee of Chamkar Leu District and supervised workers at the 1st January Dam.

Dale Lysak, Assistant Prosecutor, started the day off by confirming the details of her marriage with Ke Pauk.

She was married when she was 22, either in 1958 or 1959. (Ms. Soeurn could not recall her birth date but Mr. Lysak estimated it to be 1936.) Ms. Soeurn said she had had her first child 3 years after she was married, putting the date of her marriage in 1959.

Ms. Soeurn stated that her husband was a rice farmer at the time she was married.

Lysak read from the interview Ke Pauk gave before his death.[4]

Ke Pauk: “I joined the struggle in 1949… After the Geneva convention [1954], I abandoned the party and returned home. In 1957, the secretary of the party contacted me and .. I enlisted into the party… In 1958, after I became a member of The Party, they assigned me to conduct some activities in Chamkar Leu district, my birthplace.”

Ms. Soeurn could not confirm that her husband had been born in Chamkar Leu nor when he had joined the revolution.

Nuon Chea

Lysak continued reading from Ke Pauk’s interview:

Nuon Chea at the ECCC on the 31st of October of 2013 via the ECCC flickr (picture licensed under Creative Commons)

Ke Pauk: “In mid 1967…Brother Nuon [Nuon Chea, one of the two defendants in this case[5]] was away to Prey Chor to assign forces. In 1968, I began working in the jungle.”

Ms. Soeurn said she had lived separated from her husband since 1967 and that she had only met Brother Nuon when she came to Phnom Penh. She could not recall when that was.

Lysak reads from her OCIJ interview in which she says that she joined the Khmer Rouge in 1969 while she was living in Phnom Penh.

“Was it in connection with joining the revolution that you first met Nuon Chea?” Lysak asks.

“At that time I was told to be a cook,” Ms. Soeurn responds, “and that was the time I got to know him. Of course they discussed about the work but I did not understand the nature of the work, so I resorted to be a cook for them . . . I did not see him [Nuon Chea]. I cooked in the kitchen and it was someone else that took the food to him.”

Maquis and Pol Pot’s masseur

Lysak then referenced the “Maquis.[6]”

“You left Phnom Penh with your daughter in October 1970[7] to the Maquis, You were taken to a location in the deep forest near the Stung Chinit river where you met your husband. Was this a head quarter or base of the party where you met your husband?”

Ms. Soeurn said that she didn’t see senior leaders there, only commanders.

When asked what she meant by commanders, she said that commanders were those “related to the work of her husband.”

Mr. Lysak confirmed that Ms. Soeurn had lived in the same location as her son Kae Pichvanak.

Mr. Lysak then read to Ms. Soeurn, from the OCIJ interview of her son, Kae Pichvanak.

Kae Pichvanak testified in that interview, in the words of Mr. Lysak ,that: “between 1970 and 1973 he lived at a site in Steung Treng district, Kampong Cham. That that was the Party center Head Quarters. That, during the day he [Kae Pichvanak, Ms. Soeurn’s son] was taught by Pol Pot’s wife, whom he called Grand Aunt Ri. At night, he gave massages to Pol Pot. He call him Grand Uncle Sar alias Grand Uncle Pol.”

Mr. Lysak proceeded to ask if Ms. Soeurn had had any contact with Pol Pot. She had that she was not personally close to them.

“I met them when I was living in the forest,” Ms. Soeurn said, “I met them some time and they were referred to as Bong. When I was allowed to go and meet them I went to see them.”

Later, Mr. Lysak asked her if her husband had told her why he was promoted to be secretary of the North Zone [which would later become the Central Zone].

“What I knew was that my husband had become the Zone Secretary. As I stated, as a female I was not allowed to know the affairs in detail. . . from that time onwards people addressed him as such. I asked him about that and he told me to mind my own business.”

—

Role of Ms. Soeurn

Mr. Lysak then sought to clarify what her role during Democratic Kampuchea (17 April 1975 – January 6 1979) had been. She testified that it was in the later part of 1975 that she moved to Chamkar Leu where she was a member of the district committee. “There was only one female that was me at the time,” she mentioned.

Mr. Lysak tried to ascertain whether she had been appointed secretary of Chamkar Leu District. He read from the interview of a potential witness (2tcw950), alias Poss, who claimed that: ““Sou Soeurn was appointed secretary later, perhaps in late 1977. At that time, Un [Sector 42 Secretary and younger sibling of Sou Soeurn], removed me from my position at sector 42… and appointed me as deputy to Sou Soeurn.”

Mr. Lysak affirmed that Poss had said that she was the Secretary in a number of interviews and asked whether his testimony refreshed her memory of whether she was appointed to head the Chamkar Leu district.

Ms. Soeurn, as she would do many times during her testimony, said:

“I do not recall it well because I was not working with them. I may have forgot it because it was a long time ago and my memory [is getting] weak[er] from day to day.”

Does the witness know if her husband reported to the Secretariat?

Lysak tried to ascertain whether she knew if her husband (who, it is alleged, planned and supervised the construction of the 1st January Dam) needed to obtain approval of the leaders in Phnom Pen to build the Dam.

While Ms. Soeurn could not (or would not) confirm this. This is the exchange:

Mr. Lysak asked: “Did your husband need to obtain the approval of the leaders to build January 1st Dam?”

“I do not know when the conception of the dam started,” she said “and how long the construction lasted. I was a female cadre. I was not with my workers constantly. I do not know about this matter.”

Mr. Lysak continued to inquire as to the nature of the trips Ms. Soeurn would take to Phnom Penh, which she had mentioned before, where she had met Nuon Chea.

“I never accompanied [Ke Pauk, my husband] to Phnom Penh. I went with other female cadres… And we went to meet Nuon Chea and as I told you already I never went with my husband. We were there to attend the political study sessions. We were there to listen to the discussions of the cooperatives. We were instructed to arrange the workers properly so that we could achieve certain tones of yield per year.”

Supervision of workers

In what may have been a translation confusion, a willful or unconscious deflection, or a failing memory due to her old age ( a point Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne would come back to later), Ms. Soeurn did not confirm that she led or supervised workers at the 1st January Dam Site.

“I do not know abut workers sent to the Jan 1st site,” Ms. Soeurn stated, “and don’t know how they were selected. The secretary for the district held that list.”

“You have stated,” Mr. Lysak asked again, “that one of the responsibilities was overseeing the workers for the first January dam. “

“I have already given my response,” she said.

The president of the Court intervenes and tells Lysak to please re-phrase his question.

Mr. Lysak, reads then from her OCIJ interviews where she stated: “As for me, I only led the cooperative to build dams and canals.”

Then he asks again, “Is it not true that part of your responsibilities was building dams and canals?”

Ms. Soeurn responds: “I already told the court that I did not know the number of people at the dam site. I selected and chose people from cooperatives but I did not know how many people were there because I did not hold the list.”

“Who supervised the workers from Chamkar Leu district?”

“Each sangkat [commune] had its own chief… and I do not know the names of those sangkat chiefs. Some of them have survived maybe but they may be living a far distance from my place.”

—

Disappearances

Lysak read from Ms. Soeurn’s OCIJ statement: “Not only did ‘April 17 People’ disappear, but also ‘Base people.’” The exchange is reproduced in full below to let the reader judge and understand her testimony.

“How did you become aware that people from your district disappeared?” Mr. Lysak asked.

“What I knew, is that people were taken away for study sessions. That’s what I knew at that time,” she responded

“How is it that you knew?”

“Each Sangkat chief told me certain people were taken away to study sessions. But I did not know where they were sent to.”

“How did you know that Base People and 17 April people had disappeared?”

“I knew this from Sangkat chiefs. They told me. I was told that certain people were taken away for study sessions and for work.”

“Were there any people whose relatives had disappeared who came to ask you about them?”

“I do not know because no one came to ask me about the disappearances. If someone came to ask me about their relatives, I would tell them they had been taken to study sessions as I was told.”

Working Conditions at 1st January Dam

Ms. Soeurn stated in no uncertain term, contrary to what witness have said before, that: “The sleeping quarters for workers at the [January 1st] site were proper and [the workers] had proper living conditions. Their sleeping and eating conditions were proper.

“Can you be a little more specific? Mr. Lysak asked. “What is proper? What did you sleep on?”

“I want to say that I lived my life as other workers did,” she said. “Workers had food. Angka supported workers, they provided rice and food to work. They had decent food to eat.”

“You also said the workers receive decent food?, Mr. Lysak prompted, “How many meals and what rations?”

“As for food rations, they had two meals per day. Sometimes they had gruel and sometimes they had rice. It depended on the situation, on the reality.”

“Were there a lot of flies at the worksite?”

“Yes. But not many of them. When we were clean and when there was hygiene there were not many flies.”

Mr. Lysak then reads from an OCIJ interview of a potential trial witness 2TCW896, who allegedly drove Ke Pauk to the 1st January Dam almost every day. Ms. Soeurn cannot recall his name when it is whispered to her as she allegedly[8] cannot read.

This is what 2TC896 said:

“At that time there were tens-of-thousands of people working there. They were working hard in hard conditions. Especially the women… their buttocks were covered and surrounded by flies…at the worksite there were many flies. ”

Mr. Lysak then asks:

“Does this refresh your memories? Did you observe difficult conditions at the worksite for females and did you talk to your husband about those conditions?”

“There were many workers and of course I couldn’t… In some locations there was sanitation and of course there was plenty of water and of course some people who didn’t do their relief property there were flies. I only visited limited locations at the site.

Internal Purges

Mr. Lysak reads from parts of an S-21 list from the 8th of July of 1977 that has 173 prisoners from Ms. Soeurn zone that were murdered.

“Did you notice that virtually every cadre disappeared and was replaced from the south west zone?”, Lysak asks.

Koppe at this point objects to the use of the words disappeared because they were executed, not disappeared.

Lysak rephrases: “Did you notice that virtually every single cadre, was taken away, killed and replaced by people form the South West Aone?”

“I may not have known. I noticed that people were gone. But I did not know where they were going to. I knew only Tol but for the rest I have no idea.”

Lysak again reads from the interview of a potential interview with the alias Poss:

“After purges were conducted at the Central Zone, only four people remained: Ke Pauk, Sou Soeurn, Un and me.”

Ms. Soeurn doesn’t react.

Mr. Lysak reads her names from the list, people who served on her same district committee.

Ms. Soeurn can’t remember: “When I was a member in that district, I never noticed that name. Perhaps I have forgotten.”

“Do you know whether it was your husband that decided to arrest the party leaders or was it the leaders in Phnom Penh? Are you able to tell us that?” Mr. Lysak asks.

“Allow me to inform the court that I do not have the full graph of the information. My husband had different tasks to perform. I had no idea of what he was doing. What he was doing at the time was his responsibility. I was not involved in the arrests or any kind of things. “

“Let me read what your husband had to say at the time,” Mr. Lysak replies.

Ke Pauk: “When I was conducting an assembly in sector 41 a messenger form Phnom Penh arrived to tell me to get prepared for the inspection mission. However as I arrived in Phnom Penh, I met Pol Pot and Nuon Chea and they showed me documents… The answer was too clear to correct. .. I said it is difficult to say because all comrades are life and death friends. However, if Angka has decided I cannot refuse to comply… some had served me since 1968.. but they were accused of working for the CIA.”

“Your were District Chief,” Mr. Lysak asks, “your brother was Sector Chairman. your husband was Central Zone Secretary. Did your husband ever talk about [the purge]?

“I repeat it please to the court that my husband would know his business and I minded only my own business. So I did not know about his relationship with Angka.”

—

Mr. Seng Leang, Deputy Prosecutor, had another way to confirm her role at the 1st of January Dam site, using conditional questions:

“In the case that you received a report [about the 1st January Dam site’s working conditions], did you have to make another report to the upper level?” Mr. Leang asked.

“If I received such a report I discussed it with the district committee and reported to the sector.”

“When you received a work plan from the upper level, how did you disseminate the information?” Mr. Leang asked.

“On the issue of a work plan from upper level, the district committee held a meeting and send relevant workforces to the 1st January Dam site. The district itself did not directly supervise at 1st January Dam as we had to supervise other canals and worksites. And I usually supervised such workforce. So I really did not have detailed knowledge of conditions at 1st January Dam worksite.”

“You were the one responsible for sending tools to 1st January Dam worksite?” Mr. Leang prompted.

“I didn’t send any tools or equipment as there were sufficient tools and equipment at the worksite. I only organized the work forces to go there and they had to be self-sufficient with the tools.”

“They only utilized hoes and axes. And they didn’t have access to any machinery?” Mr. Leang asked.

“The workers of the 1st January Dam only had their personal strength with axes, hoes, poles, baskets, and knifes. If they had sufficient food they had the strength to carry the dirt,” Ms. Soeurn replied.

Ms. Chet Vanly, Civil Party Co-Lawyer, then took the floor and confirmed her knowledge of the chain of command.

“As a wife of Ke Pauk, were you aware who were his superiors?” she asked.

“I only knew that Pol Pot, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan , besides them I do not know who else. “

“Did you know how he communicated with the upper level? Telegram or messenger?” Ms. Vanly asked.

“At that time, telegram was not used, and the communication went through his messenger. The messenger would go between Kampong Cham and Phnom Penh, no telephone or mobile. Landline phone when there were explicit instructions from upper Angka.”

Then, Ms. Vanly, civil party co-lawyer, asked her yet again about the number of people at the 1st January Dam Site and the sanitation conditions there. This time she said:

“There were from 20 to 30-thousand workers. Probably that was very modest. There could have been 40-thousand. You can make your own personal imagination about the hygiene. Even in a home with three or four. You could imagine when there were 40,000 workers: people relieving themselves in the open, so [there was] no sanitation.

“From your observations, did any become ill?” Ms. Vanly asked.

“Due to sanitation and large number of flies, the medication was merely enough as we had only had come through the struggle and had not liberated the country for long,” Ms. Soeurn responded.

Questions from the bench

Judge Fenz took the floor and was able to get the witness to explain the nature of the alleged forced labor at the Dam Site:

“Could those that were selected [to work at the Dam], refuse?” Judge Fenz asked.

“No one actually refused. Once the district organized the workforce, the people did not refuse. Of course when they returned from the 1st January Dam they were happier,” Ms. Soeurn responded.

“Why did no one refuse?” Judge Fenz followed-up.

“The thing is that that was the organization by the district so they did not refuse. If we selected 5 or 6 of them they went. We all tried hard to meet the disciplines [sic] and regulations.”

“Were people ever told that they would be punished?”

“We were not told or warned. We were only told to respect the discipline. We were instructed to start and stop working.”

“Could workers refuse once they were there?”

“No one dared to refuse. Angka . . . assigned and everyone had to comply. No one dared to say that they wanted to go back.”

“Why?” Judge Fenz asks.

“Because we were told that we had to work hard so that we could solve people’s problems. We were told that we had to work to build the country. Workers voluntarily wanted to go to work,” Ms. Soeurn responds.

“Did anyone run away?”

“No one fled from their work site,” Ms. Soeurn replied.

“Why?” Judge Fenz asks.

“I do not know. I do not know the matter in detail. They were in the work even though they were exhausted and tired.”

—

Judge Lavergne was able to confirm that Nuon Chea knew about the working conditions of the 1st January Dam.

“Would Nuon Chea inform himself of the situation of the site? That people were complaining?” Judge Lavergne asked.

“He asked about it,“ Ms. Soeurn replied. “But most of the time [he asked about] how the cooperatives were organized and what was the livelihood of the people and the health situation of the people.”

Judge Laverge then asked the witness who was lying, as she had said that the Sangkat chiefs never lied:

Ms. Soeurn said: “We were told [by the Sangkat chiefs] that there was no problem with the food. I do not really understand that there was no lack of food.”

“I don’t understand either,” Lavergne replied.

“I would like to state why I do not really understand,” Ms. Soeurn said. “I knew that the rice yield was good, Sangkat chief told me there was food. But workers told me the food was not enough.”

“According to you the Sangkat chiefs were lying? There’s obviously someone who is lying,” Judge Lavergne said.

“I do not know…” Ms. Soeurn responded.

____________________________________

[1] Although there seems to be an additional witness on the January 1st Dam that may be called to testify at the end of June. [2] The Public Affairs Section of the court has clarified on Twitter that, although the closing order in this case uses both Ke Pauk and Ke Pork as spellings, the transcript of this hearing will only use Ke Pauk. [3] Here’s a good place to start learning about the relationship of the TPO and the Court. Note that during the hearings I’ve attended, both witnesses and civil parties have been assisted by TPO staff in the Courtroom proceedings. The TPO representative sits next to them at the witness stand and sometimes consoles them, holds them and, from my understanding, provides them emotional and physical support. Here (points 5 and 6) is the “Overview of Civil Party Reparation Requests in Case 002/01” that involve the TPO. [4] Referenced in the courtroom as E3/2782 or E3/2783, English ERN: 00089708 [5] The defendant Nuon Chea has not been present in the courtroom since I started covering the court. Khieu Samphan has been present every day. Each day, Nuon Chea requests to be allowed to watch the proceedings from his holding cell, due to his back pain, in order to more effectively participate in the future. Every day, the President reviews his request and a medical report ,and grants Nuon Chea’s request. [6] “Maquis” refers to the guerrilla members of the Cambodian Communist Party but also to a place as I understand it. It comes from “the rural guerrilla bands of French Resistance fighters, called maquisards, during the Occupation of France in World War II . . . Originally the word came from the kind of terrain in which the armed resistance groups hid, the type of high ground in southeastern France covered with scrub growth.” In French: “although strictly meaning thicket, maquis could be roughly translated as “the bush”. Source: Wikipedia. [7] The Lon Nol “coup “ occurred in 18 March 1970 but the Khmer Republic was only declared on the 9th of October of 1970. [8] Both the President of the Court and the Prosecution affirmed she was illiterate while Mr. Koppe, defense counsel for Nuon Chea, affirmed that he was told that she could read a little. Neither of the parties strove to confirm this although she did say she couldn’t read and that she never “had” the lists of names given to her or her district committee.