“Clothing Only Came In Two Colors: Grey Or Black”- Back to the 1st January Dam

The ECCC Trial Chamber seen in a rare photo from above. (The picture is attributed to the Court. It’s from the August 12, 2012 hearing.)

Today, on July 30, the court finished the cross-examination of witness Ms. Vat, on the Kampong Channang Airport and started with the examination of perhaps the last witness on the 1st of January Dam.

Cross examination of Ms. Vat

Witness Ms. Vat (ECCC Flickr)

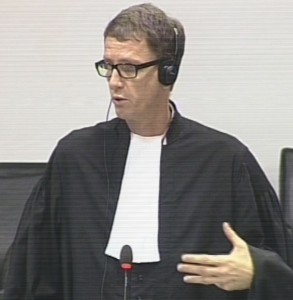

Victor Koppe, co-lawyer for Nuon Chea, started of the cross-examination by trying to ascertain whether Ms. Vat, the witness, remembers being read her OCIJ statement after she signed it. The reason he is asking her this, he says, is because he has found eight examples of possible discrepancies between what she said in her OCIJ statement and what she had testified to in court.

Ms. Vat says her OCIJ statement was long ago but “you can ask me questions,” she tells Koppe, “if I know the answer I’ll answer you, if not I’ll say I don’t know.”

Visits to KC Airport

The first example Koppe points to is that in her OCIJ statement she said she went three times with the Chinese to the Kampong Chhnang (KC) Airport while yesterday she had said that she went to the KC Airport for the first time when she got married and cooked for the Chinese during that time. The President interrupts and asks parties to read the transcript well as she had said that the Chinese had gone three or four times to the KC Airport, not her. Koppe moves on.

Suicides

His next example of a discrepancy is pointing out that in her OCIJ statement she had said that suicides happened “very often,” while yesterday she had given two examples. Ms. Vat responds: “I don’t know about very often. I know one case about one man who ran into a truck and killed himself.”

Koppe moves one to asking her about whether her husband was the commander of the children handicapped unit in 502. Ms. Vat says he had a supervisory role but doesn’t know his rank. She said that he was handicapped, he had a leg wound, and was from Division 11.

Forced Marriage

Ms. Vat confirms that she was forcibly married to her husband, Load (phonetic). “I had to follow Angka,” she says. “they said that Angka required me to marry a man at KC Airport,” she continued, “They told me to be ready at 5 a.m. the next day to go there. I did not know my future husband. I learned his name at the ceremony (though later she said she was told his name earlier). I had never seen him before.”

Joined the revolution

Ms. Vat said that she committed to follow the revolutionary line when she joined the revolution in 1970. The line was that the revolution was there to liberate the country from the capitalists and feudalists who were oppressing the poor. When asked what that meant, she said that “the capitalists were the rich who oppressed us and did not give us freedom of association and freedom to make a living.”

KC Airport

Ms. Vat said that Division 502 was in charge because it was also known as the the air force.

Koppe attempts to ask whether going to the KC Airport and working there was part of her normal duties as a solider. He asks if it was an ordinary order to be sent there. Marie Guiraud, International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer, objects as yesterday she had clearly said that she felt that going to the KC Airport was punishment. She also objects on the ground that it is a leading question. Judge Lavergne adds his voice and asks Koppe to explain what he means by an ordinary military order as opposed to an extraordinary military order.

Koppe responds that they’re not mutually exclusive. He thinks it could be a military order that is felt to be like punishment. The president sustains the objection and asks Koppe to rephrase.

Ms. Vat responds that she was no longer a soldier. After her husband disappeared, she says, she was deprived of her status as a soldier and ordered to work as an ordinary worker. She confirms, due to Koppe’s insistence, that she did not receive an official letter of discharge from the army.

Ms. Vat would later say that when the Vietnamese arrived in 1979 she escaped in a military truck.. Mr. Koppe asks if escaping in a military truck does not mean that she was still part of Division 502 of the Air force. Mr. Far objects on the grounds that he’s making an argument. Koppe explains that there are secondary sources that say that many soldiers were discontent but they remained soldiers. Mr. Farr says it is still an argument. Ms. Guiraud rises to say that she has already said that she was not a solider. The objection, though, is overruled.

“I was still attached to 502,” Ms. Vat finally says. Koppe sits down

__

Anta Guisse, co-lawyers for Khieu Samphan then takes the floor.

Ms. Vat confirms that she was married in late 1977. She spent a week in Kampong Chhnang Airport after her marriage and worked as a a cook. Her husband would visit her at night.

Ms. Vat was instructed to lead the group of married women, the wives of soldiers (she also called them old ladies or women with children) from force number 2 to make fertilizer.

Ms. Vat explains that immediately after she arrived at KC Airport, she rested for one day at her location near Prateath pagoda. One day after that, she says, there was a meeting where she was assigned to lead the old women in force number 2.

Ms. Vat does not know if workers or soldiers were sent to fight the Vietnamese.

She also does not know the name of the driver who told her about the suicides.

She does remember who told her about the Khieu Samphan visit. It was man named Sokhun. He was working with the Chinese, Ms. Vat said. She confirms that Khieu Samphan was referred to as Uncle Number Two.

Mr. Kong Sam Onn, co-lawyer for Khieu Samphan, confirms that she might have arrived at the KC Airport in mid-1978 and not in 1977 as she had said before.

—–

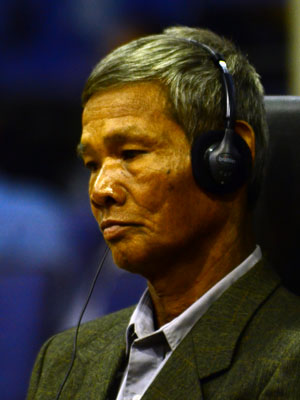

After lunch, the court started hearing witness Mr. Oum Chy. He was born in 1952 in Chey Mongkol village, Balangk commune, Baray district, Kampong Thom Province. His father’s name is Oum Chum, his mother is Sun and his wife is Hen Vuth. They have six children together.

He was interviewed once by the OCIJ in 2009, at 10 a.m. he says.

The President says that the witness is “rather busy with his business so please reduce your questioning time.”

—

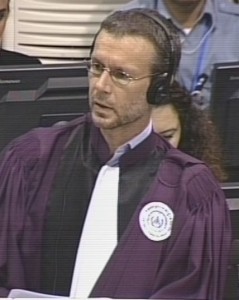

Mr. SENG Leang, Deputy Prosecutor, was given the floor first.

In February 1978 Mr. Chy says he was assigned to build the canals for the 1st January Dam. He says he was mobile unit chief. He had 500 people (all of them unmarried) under his command.

He said that when he arrived, the Dam was already built. He said his project of building canals was linked to the the 1st January Dam. He said the project belonged to the Sector and there were five to six-thousand workers.

The location of the dam was between Chung Doung and Balangk communes.

Within the scope?

Koppe objects on the grounds that his testimony is outside of the scope of the trial as he did not work on the 1st January dam.

Vincent de Wilde retorts that paragraph 352 of the closing order specifically mentions a whole series of canals linked to the 1st January Dam. He says it is well within the scope of the trial and the closing order.

Anta Guisse asks the prosecutor to clarify whether this canal is linked to the Dam.

De Wilde replies that “if you look at a map from the time, it’s right there in the 1st of January dam.”

The president overrules the objection and says his testimony is within the scope.

Forced Labor?

“Nobody actually volunteer to go work there,” he said, “We were forced to go there.”

Mr. Chy then explains that in his 500 member unit, “no one volunteered to engage in this kind of hard work.” When asked why, he responds:

“During the regime, including myself, we could not refuse any kind of work. During the regime, throughout the country, everybody had to adhere to the principles. Otherwise we would be accused of opposing their society. It means that you would put yourself in a risky situation and would be sent to re-education at the detention center or the commune office.”

Mr. Chy says that workers could seek permission to visit their children or wives if they were sick. When Leang attempts to ask “What if they missed their family,” the President interrupts without any objection and disallows the question on the grounds that it is a hypothetical question. Instead of rephrasing, Leang moves on.

Work Schedule at 1st of January Dam

Mr. Chy confirms that the working hours were from 4 to 11 a.m., with a 15-minute break between 9 and 10 a.m. Lunch was from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m.. Work started again at 1 p.m., to 5 p.m., with a 15 minute break between 3 and 4 p.m. “When the work was demanding,” he said, “we continued from 6 to 11 p.m.,” he added.

“Persons in my unit were not happy,” Mr. Chy exclaims in the low gruff voice he has had all morning, “as they were too tired. However, there was nothing we could do, we had to follow their instructions. During the regime, nobody dared to protest, we had to carry out the game plan.”

When Leang attempts to ask what would happen if someone protested, the president interrupts him again without an objection to disallow the question. Instead of rephrasing, Mr. Leang moves on.

Quota

Mr. Chy says that only 60% of his workers could complete the quota of 3 cubic meters per person per day. In his OCIJ statement, Leang says, that only 30% could meet the quota. He also says there that he told lies about everyone meeting the quota to upper Angka in the report that he submitted, and that is why workers were not punished by him for not meeting the quota.

—

Mr. Vincent de Wilde, Senior Assistant Prosecutor, then takes the floor.

Mr. Chy confirms that the project was closed down in August 1978. The group that he led of 500 members was composed both of “New” and “Base” people as well as Cham. They were all from different villages in Balangk commune.

Mr. Chy says he conducted meetings to relay instructions to the small unit chiefs. He says he did not chair criticism or self-criticism meetings. Those meetings, Mr. Chy said, were led by the unit chiefs and were held at night, after dinner time.

The policy of the Khmer Rouge regime to build dams was to get water to the rice fields and so obtain the 3 tones of rice per year. He does not know were the rice that was produced was taken to afterwards. “Angka took the harvest away in order to give it to the military,” Mr. Chy said.

Mr. Chy confirms that he does remember people at the sector and district committee that discussed “enemies. “Anyone who violated the regulations would be considered an enemy,” he explained. “Regarding the fate of those people, I heard [from the district or sector chiefs] they would be smashed as they were interfering with the construction.” They were referring to anyone who would sabotage the movement.

Arrests

Mr. Chy also witnessed people being arrested. He says he saw an 18 or 19 year old worker arrested from a nearby commune. He said the reason that this worker was arrested was to deter other workers so that they continued to work hard.

In his OCIJ statement, Mr. Chy had said that “One day I saw a child. He was talking and he was arrested by the internal security agents. He was called to the top of the dam where he was publicly arrested.“

When asked if people were prohibited form chit-chatting with their friends, Mr. Chy explained that “during the regime, we were prohibited from talking with one another about anything that was not compliant with the principles of the party.”

He says he also heard about his neighbors being arrested.

“Anyone who was arrested, never appeared again,” he added.

Wat Baray Choan Dek

Mr. Chy confirms that the Baray Choan Dek Pagoda was the security center of the village of Trop.

Koppe attempts to objects, as he has in the past, that the Wat Baray Choan Dek is not part of the 1st January Dam Site and it is outside of the scope. The objection is overruled again.

Mr. Chy said he heard about it being a security center. He said he attended meetings at the Pagoda, but explained that it was after office 870 had sent an order to move the security center.

He said that during those meetings at the Pagoda, he saw traces that this place had been used as an execution site. “I actually saw that blood stains remained in the walls of the temple and the dining hall and I saw remnants of torn pieces of clothing on the ground.”

“Were there still odors of corpses when you were there?” de Wilde asked.

“Yes the bad odor was still lingering in the air while I was there.”

Working Conditions

Mr. Chy explained that clothing during the regime only existed in two colors, grey and black and most workers only had one change of clothes.

He explains that the water was unsanitary. It was from the river and it was used by workers to clean themselves and also to drink.

He also confirms that medics were all young (14-18 years old). They only got a short training and they used the traditional medicine that was called “rabbit-drop pellets.”

New People

In his OCIJ statement, Mr. Chy said that around 20 families from Phnom Penh arrived at his village after they were evacuated in Phnom Penh on April 1975. Some of them were Cham. He said that first they were allowed to live in the houses of the “Base People.” Later on, huts were built for them. “And these people were dispersed everywhere in the villages,” he said.

Mr. Chy said that there was a plan to purge people in 1977, but he says he was transferred 20 k.m. away then and does not know who carried out the purges. But, he says, that when he came back to his village to visit, he heard that five families had been purged.

Mr. Chy does remember the name Ke Pauk, but said he never worked close to him. He also remembers that Ta Oeun was the chief of a sector.

He also remembers when the South West cadres took over. “But I did not dare to ask where the South West Zone was,” he said.

Mr. Chy explains that marriages were arranged. Their biographies were matched and if they were from the same group, that is the same peasant class, or if they were “!7 April People” or Cham, for example, he said, they would be arranged to be married.

__

Mr. Victor Koppe, co-lawyer for Nuon Chea, starts the cross-examination.

Mr. Chy confirms that in the period when he worked at the Dam, from February 1978 to August 1978, the 500 workers he led were not always the same, some of them got sick and some of them went to other units. He explains that in August he was forced to be married and was transferred to live in a village.

In his OCIJ statement he had said that four or five out of five hundred workers got sick during his time there. Mr. Chy says that he recalls it now and that they were sent to the hospital but cannot remember the names.

Mr. de Wilde asks the defense to clarify whether it was during the whole period or every day.

Mr. Chy then says that sometimes in one day four to ten people were sick. He then repeats that it was five to ten people daily who got sick. He explains that since he had not elaborated before that is why “you’re making accusations against me.”

Koppe then asks about the young boy who Mr. Chy had said had been arrested to deter workers. Mr. Chy said he had not spoken to anyone who had arrested him. He said that there were arrests and they were done for no other reason than to deter workers. Koppe insists it is just speculation on his part.

Koppe reads from the propaganda magazine Revolutionary Flag of October 1977: “Our experience has been that night work has few benefits: health-wise, and use of electricity but the biggest losses from night work are political and ideological.. “

Mr. Chy said that at the 1st of January dam sometimes they required them to work at night and they could not refuse.

Mr. Chy said that unit chiefs decided if people could bring personal belongings like hammocks and sleeping mats to their sleeping quarter. Some people had these belongings and they could bring them. If they did not have them, they would sleep on the floor, Mr. Chy said.

Koppe asks Mr. Chy asks to explain what he meant by his earlier statement: “enemies were smashed who may sabotage the movement.” He said that meetings were held to figure out who had committed sabotage and they were taken away to be re-educated or tortured. “I never witnessed the actual torture,” he said, “as I slept in a different place than my workers.”

Mr. Chy explains that Poch replaced his superior Mul after he was transferred elsewhere. He says that he was in the district committee. He did not hear any stories about Poch being cruel or killing families without the organization’s approval. Chy explained that Poch only arrived after the purge.

Judge Lavergne asks Koppe what the sources for his allegations against Poch are. Koppe says it is an OCIJ interview of the son of Ke Pauk.

Mr. Chy insists that the killing of people only happened before Poch arrived.

Mr. Koppe then reads a story from the son of Ke Pauk that tells how Ke Pauk saved 200 families from being executed. Mr. Chy does not know about this.

Mr. Koppe then asks if he had heard of weapons being given to Tol (who was replaced by Oeun (brother-in-law of Ke Pauk) coming from Division 310. Mr. Chy says that his position at the time would not have allowed him to know such sensitive information.

Ms. Anta Guisse, co-lawyer for Khieu Samphan, then takes the floor.

Mr. Chy confirms that he is not familiar at all with the construction of the 1st January Dam. When she attempts to ask whether the canals actually connected to the 6th of January of Dam, Mr. De Wilde objects and Ms. Guisse attempts to preempt the objection. Nevertheless De Wilde, objects that the witness has never mentioned the 6th January Dam. When Guisse asks to which dam were the canals connected to, Mr. Chy confirms it was the 1st January Dam.

Mr. Chy says that he only visited the 1st January Dam after 1979 when he would ride his oxcart over its crest. “During the regime,” he said, “I would not have the liberty to go anywhere except the work assignment at the specific locations.”

He said that he was chosen to be the head of the unit to build the canal because he was single at the time and was a bit older than the others. He confirms that members of the mobile units were all single. Mr. Chy says he did not appoint of his subordinate as they had already been appointed.

He confirmed that “Base People” and “New People” were not treated any differently and they worked together as a team.

Chy says that he never authorized corporal punishment. He said that his subordinates came to him to ask for permission to punish some people but, he said, he never agreed.

The re-education meetings were not held once a day but sometimes once every week.

Mr. Chy says that the rice was not enough for the workers. He says that he did not authorize fishing because if the commune were to find out, they would cut off their food ration. “It was against the principle that the commune was in charge of the ration.”

Ms. Guisse cites the testimony of Mr. Ar Ho (which you can read about here), whom she characterizes as another unit chief, that had said that he had allowed his workers to catch fish.

Mr. Chy says that Ar Ho was not a unit chief but a village chief. He said that village chiefs could do that, but it was not the responsibility of the Unit Chief like him because for them the food was rationed and they did not dare look to supplement the ration.

He says that he dared not asked for more food as people would say that the food they were being sent was enough and if they complained they would say they were not sufficiently tempered.

Mr. Chy said that because of the lack of equipment he did not give instructions to constantly boil water for his workers.

Pagoda

Mr. Chy confirms that he did attend a meeting at the Baray Choan Dek Pagoda.“If you do not believe me,” he says “you can go ask the people that lived next to that Pagoda.”

Guisse confronts Mr. Chy with the testimony of witness Meas Hour who had said that Pagoda remained a security center until the end of the regime. Mr. Chy explains that the security center was transferred to the Kampong Thma market and some people might not have known that.

To Mr. Kong Sam Onn, he says that he was a unit chief at the commune level. The commune chief to whom he made reports to was Duong.

He said that he asked his subordinates to tell their workers not to wander around because if Angkar found out they all would be in trouble.

—

Hearings will recommence on the 10th of August, 2015 with the continuation of the Trapeang Thma Dam segment. The parties have been given a week to catch up on the disclosures made by the prosecution.