Major Disagreements on Questioning of Civil Parties

In today’s hearing in front of the ECCC a heated discussion unfolded revolving around the distinction between witnesses and Civil Parties. Defense counsels for Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan argued that a Civil Party should not be questioned on facts, while the Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers upheld their position that Civil Parties can also be asked on issues not directly related to their suffering. Civil Party Nhip Horl described working conditions at Trapeang Thma dam construction worksite.

Working Conditions at Trapeang Thma

Trial Chamber Greffier confirmed the attendance of all parties, except Nuon Chea who participated from the holding cell. The testimony of Civil Party Nhip Horl (2-TCCP-269) began. He was born in 1952 in Roul Chruk Village, Preah Net Preah District (then Battambang, now Banteay Meanchey), where he also currently resides.

Civil Party Nhip Horl

The floor was given to the Civil Party lawyers. Lor Chunthy, Civil Party Lawyer from Legal Aid of Cambodia, started first asked introductory questions. Mr. Horl lived in his birth village until it was liberated by the Khmer Rouge on the 17th of April 1975. Then, he was transferred to Chroab Thmei village, being assigned by the Khmer Rouge to stay there for three days, because, so he was told, they were afraid of the aerial bombings by the “American fighters.” All villagers were evacuated. No accommodation was built for the evacuees. A few people had oxcarts where they kept their belongings. After these three days “no one had the courage to come back”. He was then part of a mobile unit to harvest rice in Sala Kraham, Serei Saophoan District.

Turning to the topic of health conditions, Mr. Chunthy inquired whether Mr. Horl fell sick. The Civil Party replied that his “health situation was terrible.” He hadto “do the work for the sake of my life. If I refused the assignment … I was afraid of Angkar”. Mr. Chunthy further questioned what Mr. Horl was told the consequences would be if he refused the assignment. Mr. Horl replied that he was told that they had to respect the instructions. With regards to his disease, he contracted a disease at Sala Kraham while working. “I vomited blood out of my mouth. There was no medication for me.” He was taken to a hospital at Sala Kraham at night time. He told the court how he had been lucky: “They intended to bury me at the time, because they thought I died already. But when they noticed that I could move my limps, they took me back”. His family members did not know about his health conditions. “Kinship relationship between human beings did not exist at the time.”

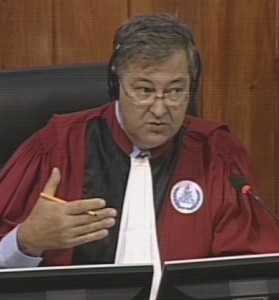

Civil Party Lawyer Lor Chunthy

Moving to his next topic, Mr. Chunthy asked at what point in time Mr. Horl was sent to work at Trapeang Thma dam construction site. The Civil Party replied that he was sent to Kang Va to pull out rice seedlings ten days after the recovery of his disease. Kang Va was one of the worksites growing cotton during the period of the Khmer Rouge regime. It was located in Serei Saophoan District. Later on in June 1977, he was transferred to Trapeang Thma “to carry dirt”.

Upon their arrival at Trapeang Thma, hoes and baskets were given to them. The following day in the morning, they were shown the plot of land close to Bridge Number 1. Upon his arrival, halls that could host around 100 people had already been built. They were located in Trapeang Thma village one kilometer away from Trapeang Thma construction site. His unit was a 100-member youth unit. “No middle-age people” or female youths were included in his unit. The members were from different villages in Sector 5. His unit was at the sector level.

Mr. Chunthy proceeded to ask whether workers were allowed to communicate and whether there were people from outside Battambang province. The Civil Party replied that he could not recall this well, since he had forgotten the people in his unit. However, he could recall that there were people from other places, including some 17th April people.

Mr. Chunthy then inquired who distributed the hoes and baskets and who defined the quotas. To this, Mr. Horl said that these baskets and hoes were given to workers individually. They would allocate five cubic meters per workers, which they measured for them. Asked how this quota was measured, Mr. Horl replied that they would put a sign per day and measure it on a daily basis. According to Mr. Horl, the food ration was given at the place where they were digging.

Asked whether the five cubic meters were immediately assigned when they arrived or were gradually increasing, Mr. Horl answered that they gave them three cubic meters at the start. If they could complete it earlier, the quota would be increased to five cubic meters. There was no specific procedure: they simply increased the quota if the workers could finish the three cubic meters earlier. Mr. Chunthy then asked whether all members were able to fulfill the quota once it was increased to 5 cubic meters. Mr. Horl replied that they did not have any other tools than hoes and baskets. They would step onto the earth in the basket to press it down to fit more in. If it was dry soil, it was rather light. When the soil was moist, it could have been around twenty kilograms per basket. He stated that “sometimes we had to help each other.” When one was able to finish earlier, one would help the other.

Mr. Chunthy then turned back to the issue of measurement and asked how this was done and who measured it. Mr. Horl replied that the unit chief had to report to the construction site chief. There was a working group on measuring the workload of each worker.

Next, Mr. Chunthy inquired about the working hours. Mr. Horl replied that they did not define the work hours, since the workers simply had to complete the work quota. They would get up at 3 am, sometimes at 4 am or 5 am. In the mornings, “they would wake us up” under the direction of Angkar.

Living Conditions

Turning to the topic of food rations, Mr. Chunthy queried where they had breakfast. Mr. Horl replied that there was no food in the morning. They were only given food in the break time at noon. At noon, they were given a bowl of porridge and morning glory or lily-plants. Sometimes they also had soup with dried fish. Mr. Horl stated that this was not proportionate to the work they had to do, but they had to do it “because we feared for our lives. We had to work. Actually, we tried to work, but physically we could not endure. But we had to do it out of our fear for our lives. We dared not to protest against Angkar.”

Mr. Chunthy then asked whether there was any instance where he was not given any food. Mr. Horl replied that when they were building the dam, they never encountered such a shortage. However, when they were working on rice fields in the dry season, they did not have rice to eat until 4 pm sometimes when they delivered the rice. Mr. Chunthy asked, focusing on Trapeang Thma, whether Mr. Horl could look for other food elsewhere to supplement their food rations. Mr. Chunthy confirmed this, stating that they could do so after having finished the work quota. They “usually dug for the roots of the plant in the bush”. According to Mr. Horl, this plant grows naturally with the rice in the rice fields.

Mr. Chunthy further inquired whether anyone in the Civil Party’s unit fell sick due to the working conditions and the food rations. Mr. Horl affirmed this, but could not remember their names. As for medicine, Mr. Horl said that sick workers received smaller food rations – but he could not recall whether there were any physicians or medics. The most common disease was pain in their chest due to overwork. They also suffered from other diseases, but Mr. Horl could not remember which ones. He further stated that “I think our immune system got used to these kinds of food and water conditions, […] so our immune system resisted”. Mr. Horl could not recall whether other workers at Trapeang Thma also vomited blood. He could only remember that there were people who had chest pain. Asked whether sick people would disappear sometimes, Mr. Horl said that they would be referred to the hospital. After having recovered, they would be sent back to their respective units.

Mr. Horl stated that he was at Trapeang Thma for “perhaps six months.” Within these six months, he did not have time to visit his family. He did not even know where his family members were living at the time.

Asked whether he got married during that time, he stated that he was a “single youth” within his mobile unit. Mr. Chunthy then asked whether he had ever noticed marriages.

Admissibility of Mr. Horl as a Civil Party

At this point, Mr. Koppe intervened, stating that he was not objecting to the last question, but remarked that in his capacity as a Civil Party, he would have to give testimony about his injury which were the direct effect of his working at Trapeang Thma dam site.

Mr. Koppe then pointed to the criteria that apply to be admitted as a civil party, which were also mentioned in the person’s civil party application [1]. These criteria are: the injury must be (a)material, physical or psychological and (b) the direct consequence of the offence. Mr. Koppe questioned whether the harm suffered by the Civil Party was a direct consequence of his working at Trapeang Thma Dam and posed the question whether Civil Party lawyers should not focus more on the suffering of the Civil Party. “I’m lost to why this person is not just a witness and why is he a Civil Party?”

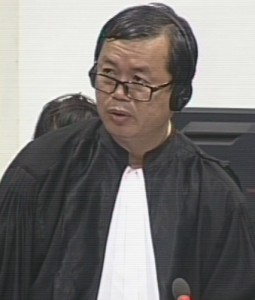

National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang

Ms. Guiraud replied that “At the point in time, it would be important for the defense of Nuon Chea to read the internal rules, understand what is a Civil Party and to understand the rules of admissibility of Civil Parties. The defense should have done this during the investigations and it didn’t do so and is making this objection today, belatedly.” The person had been admitted as a Civil Party by the Co-Investigative Judges and was to testifying today. “It is entirely proper that this Civil Party should testify regarding facts that occurred.” Further, the defense should “stop objecting […] and understand somewhat what we’re doing in this trial.” Mr. Pich Ang supported this argument, stating that “The civil party here is talking about his experience within the scope of the trial. […] And also in relation to Case 002/1 the Civil Party has the right to mention facts, as long as these facts are within the scope of the trial.” According to Mr. Ang, the Civil Party had the right to state all the facts and sufferings; the defense team should therefore not have brought up this matter.

Mr. Vercken pointed out that the objection by Mr. Koppe occurred at a point when the Civil Party lawyer questioned the Civil Party about an issue that was not referred to in his Civil Party application, that is marriages. Insofar as they are dealing with a CP, he can confer with his lawyers. He further stated that the Civil Party lawyers were looking for elements that were not referred to in the application to fill gaps in other testimonies. “There is no distinction being made between a normal witness which should testify to facts, and a Civil Party whose status is completely different.” Hence, “we should agree that points not mentioned in the Civil Party application should not be mentioned before this chamber during this hearing.”

The president reminded the parties that the court had to be clear as for the separation of status of between a civil party and a witness. Because of the suffering one endured he or she may apply to be a Civil Party. So, “the facts that we are going to explore are not the major point that we want to know. However, they are relevant.” He confirmed the defense’s position that if that person is here to be a witness, the questioning should focus more on the facts than on the suffering. A Civil Party testimony should focus on the suffering that this Civil Party endured, and facts are supplementary. Moreover, some of the questions the lawyer posed might have been out of the scope. This may cause problems with the proceedings. At this point, the president adjourned the hearing for a short break.

Work Quotas

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

At the beginning of the next session, Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud pointed towards Trial Chamber Decision E315/1, where it had been ruled that a Civil Party could testify both on facts and sufferings. “It’s very clear, and this has been the jurisprudence of your Cout.” She argued that what took place before the break seemed to have completely reversed the chamber’s own jurisprudence. Further, the defense had always put questions on facts to the Civil Parties. The president intervened and instructed Ms. Guiraud to file a written submission to the Chamber.

Next, the National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang took the floor. He asked how Mr. Horl was able to accomplish five cubic meters per day. To this, the Civil Party replied that those who were used to working could complete it, but for those who had never done such work it was too much. Mr. Ang interrupted the Mr. Horl, asking about the distance between where they had been digging the earth and where he had to build the dam. Mr. Horl replied that it was 30-50 meters away, going uphill. As the dam got higher, they had to walk up higher. They had to run.

Asked whether there were any meetings organized by the supervisors, Mr. Horl replied that there were “fairly frequent” meetings to set out the work plan. Around three, ten or 30 members took part in such a meeting. Mr. Horl further explained that they had to “reiterate our commitment” in these meetings. He was not entitled to refuse work allocations. If they were sick, they had to go to the hospital, but “we never knew where the hospital was at Trapeang Thma worksite.” He did not have time to walk around or visit his friends. “We never thought of looking relatives, for parents, or friends to visit”. Workers were not allowed to talk to each other, since they had to focus on their work.

Visit at the Dam

Mr. Ang then asked whether Mr. Horl saw any guests at the dam. Mr. Horl replied that once, they were asked to “line up”; there was one youth queue from Trapeang Thma to the first bridge to welcome the guests. He did not know when this took place and who the guests were. He only saw the “black colored cars” when they arrived.

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Arthur Vercken

When Mr. Ang asked how the queue was arranged and whether “the healthy ones” were required to stand in the front rows, Mr. Vercken intervened. He stated that “in a trial in France”, a Civil Party would have been questioned by the investigating judge. This had not happened here. What the person was talking about had never been stated in the civil party application. Without the investigative judges interviews, “mixed with the fact that the civil parties can speak to their counsels”, was rather remarkable. Mr. Vercken wondered how the chamber could allow to hear the testimony about facts that were never mentioned in a Civil Party application. The president gave the floor back to the Civil Party Lead Co-lawyer, since the observations made by Mr. Vercken were incorrect: internal rules allowed for such questions, since this line of questioning was relevant for the facts.

Turning back to his question, Mr. Ang asked about in what manner people were queued. Mr. Horl replied that only the healthy workers were allowed to welcome the visitors. Mr. Ang then asked whether the Civil Party had proper clothes at the worksite. Mr. Horl replied stated that they had sandals made out of used tires. They used old blankets to make clothes. As for sleeping, they had bamboo sticks that they laid on the ground. With this, Mr. Ang finished his questioning.

Back to Working Conditions

Deputy Co-Prosecutor Srea Rattanak took over the floor. He directed the discussion back to the issue of quota by asking when Mr. Horn received the specific assignment of five cubic meters. Mr. Horl answered that the five-cubic meters assignment was a special task in order to complete the first bridge. He could not recall how long he had to do this assignment for; it lasted until they completed the construction of the first bridge.

National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Sri Rattanak

Mr. Rattanak asked how working conditions under the assignment of five cubic meters were different in comparison to ordinary work conditions at the dam. Mr. Horl replied that they had to get up at 3 am and work until 5 pm. Mr. Horl replied that people who could not fulfill the work quota were mostly women, but he did not know what would happen to them. According to him, his unit could fulfill the assigned quota.

As regards his earlier statement that he worked “out of fear”, Mr. Horl stated that he was afraid of being taken away for execution and of disciplinary directions of the Angkar. However, he never saw any punishment at the construction site. During an extraordinary work assignment, he had to get up very early in the morning and they did not have time to rest. He did not have any additional work assignments.

At this time, Assistant Prosecutor Mr. Joseph Andrew Boyle took the floor and asked whether Mr. Horl had ever heard any worker being referred to as “lazy”, which Mr. Horl answered in the negative. Asked about the “Special Case Unit”, Mr. Horl stated that he did not know what this was. He was not instructed to write a biography – when he said that he did not know how to do it, they did not force him.

Assistant Prosecutor Joseph Andrew Boyle

Mr. Boyle then asked whether Mr. Horl or other members of the unit were being monitored while working at the dam site, to which Mr. Horl replied that he “was not interested in who monitored whom. I was much interested in restoring to sleep when I had no longer energy. I did not spend time chit-chatting with anyone.” Asked whether he was aware of anyone who was a former Lon Nol official, Mr. Horl stated that he did not know. Mr. Boyle then inquired whether the Civil Party became aware of any cadres from the Southwest arriving at the dam site, to which Mr. Horl replied that he heard of them, but he did not know them.

Neither did he did witness arrests, nor did he know about any disappearances at the worksite.

At meetings, the work plan would be set out by the 100-member unit. He did not receive a date by which the date would have to be finished by. Mr. Boyle then asked whether the Civil Party had ever heard Trapeang Thma being referred to as a “hot battlefield”, to which Mr. Horl answered that he did not. With this, Mr. Boyle concluded his line of questioning.

At this point, Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne took the floor to put some follow-up questions to the Civil Party. He inquired whether he went to the Trapeang Thma construction site in June 1977, which Mr. Horl confirmed. As regards his illness, Judge Lavergne inquired when this took place. Mr. Horl replied that it was four, five or six months after having recovered that he was transferred to Trapeang Thma. He asked the Civil Party to confirm whether he was harvesting and transporting rice; Mr. Horl replied that during the day he was assigned to harvest rice and to carry rice sacks at night time. Judge Lavergne then asked whether the food rations were sufficient there, which Mr. Horl denied. Mr. Lavergne further inquired whether he knew where the bags of rice were being catered to, which the Civil Party denied. He stated that he loaded the bags of rice on the wagons of trains. Mr. Horl denied that there was rice being brought with trains, but that salt was transported to the region. Mr. Horl was assigned to transport rice and salt. Mr. Horn could not recall how long this lasted, nor could he remember how many times trains arrived.

Back to Mr. Horl’s status as a Civil Party

Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

After the morning adjournment, the floor was given to the defense team for Nuon Chea. Defense counsel Mr. Victor Koppe took up his line of questioning by asking whether his understanding was correct that the Civil Party did not get sick while working at Trapeang Thma. Mr. Horl confirmed this. Mr. Horl also confirmed that he did not get disciplined while being at Trapeang Thma. Further, he confirmed that he did not get injured by an accident and that he was not beaten or physically mistreated by anyone at the dam. However, he was assigned to do certain tasks “in an absolute manner.” Finally, Mr. Horl confirmed that he never witnessed mistreatment or killing of co-workers. “I never witnessed that kind of savagery.”

Asked whether he had ever suffered loss of material property, such as income, Mr. Horl replied that “since I had nothing, so I lost nothing.” Mr. Horl, however, said that he is suffering from post traumatic stress disorder due to his experiences and is very anguished. Mr. Horl is not seeing any psychiatrist. This prompted Mr. Koppe to ask how the Civil Party knew that he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. Mr. Horl replied that he did not know who to talk to, but that he suffered on his own. Mr. Koppe then asked whether the Civil Party was able to make a connection specifically between the work at the dam and the post-traumatic stress disorder that he is suffering from at the moment. Mr. Horl answered that his mental condition was because of the working conditions at the dam site.

President Nil Nonn

Mr. Koppe then referred to Mr. Horl’s Civil Party application [2], where he had described his suffering but not indicated that he had suffered psychological trauma from the work at the dam. Mr. Boyle interjected, stating that the Civil Party Application mentioned that he was “overworked until he became terribly weak.” At this point, Judge Fenz intervened, asking what the relevance of this questioning was, since Mr. Koppe seemed to question the admissibility of the Civil Party. She stated that this already took place in pre-trial stage and there was a decision. “If you want to know why this person has been admitted, I’m sure you can read the decision. Beyond that, what is the relevance of these questions?” Mr. Koppe replied that the relevance was Rule 23 quinquies, where it is stated, as he interpreted it, that even if an accused is convicted, the chamber may only award moral and collective reparations and that moral reparations are reparations that acknowledge the harm suffered by the Civil Parties as a result of the commission of the crimes. What happened to the Civil Party at the hospital six months before working at the dam is nothing that Nuon Chea would be convicted for. Judge Fenz insisted that the decision whether this person was a Civil Party had already been made in pre-trial, “we cannot re-open this here.” Mr. Koppe said that “he is one of 40,000 Civil Parties. How were we ever in a position to challenge the merits of an application? This is the only time we can do it.” Judge Fenz restated that re-opening the admissibility of a Civil Party on trial is not possible under these internal rules. Mr. Koppe stated that he was not challenging the admissibility, but the connection between the harm suffered and the crimes, which needs to be established in order for the chamber to grant the Civil Parties reparations.

Ms. Guiraud stated that Civil Parties are no participating on an individual basis, but on a collective basis instead. Reparations are given to the group as such and not an individual. “the defense had the possibility of appealing the admissibility” before the investigative judge, which was in 2010 – which neither the defense for Khieu Samphan nor for Nuon Chea did. “I think it’s good to remind you of the basic rules”, she went on.

The president instructed Mr. Koppe to continue his line of questioning. Turning to his last question, Mr. Koppe inquired why Mr. Horl chose to become a Civil Party instead of remaining a possible witness.

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne

At this point, Judge Lavergne took the floor, stating that this question was inappropriate, since the person had the right to be a Civil Party and just used his right. Mr. Koppe replied that he was entitled to ask the question, because this Civil Party might not be aware that he is not questioned under oath, which meant that the evidentiary value is much lower than that of a witness. Judge Lavergne asked whether with this Mr. Koppe wanted to say that he was advising the Civil Party as a defense lawyer. Judge Lavergne went on saying that “this is becoming completely surrealistic.” Mr. Koppe stated that why of the 20,000 people working at Trapeang Thma worksite, the Civil Party lawyers picked this one to appear, and “this is a mystery to me.”

Ms. Guiraud stated that she could not accept that the evidentiary value of a civil party is less than that of a witness. According to her, it has to be examined on a case by case basis.

With this, the floor was given to the Khieu Samphan defense team. Mr. Vercken briefly stated that “we have reached the limits of this hybrid procedure. And that’s the problem. We cannot challenge the credibility of the civil party, because he has not been interviewed by a Co-Investigating Judge.” This means, according to Mr. Vercken, that the link between his harm suffered could not be challenged. “In my eyes, we have reached the limits of the logic of this trial.”

Working at Trapeang Thma and Earlier Life of Mr. Horl

Mr. Kong Sam Onn started his line of questioning by inquiring about the topic of biographies.

Mr. Ang objected to the question, stating that the conclusion was already entailed in the question and did not correspond to what the Civil Party had said earlier. Mr. Sam Onn rephrased the question, asking whether anyone came to ask the Civil Party to produce his biography, which Mr. Horl denied.

Mr. Horl stated that at Bridge Number 1, there was not enough earth, so his unit was responsible of digging the soil for the bridge. They were working next to the bridge, and not at the bridge itself. Mr. Sam Onn then went on to ask whether Mr. Horl saw any warehouses or offices next to the bridge, to which Mr. Horl replied that he did not pay attention and did not remember. Mr. Horl’s unit was around one kilometer away from the bridge.

Mr. Horl was unable to give a specific time frame that he worked at Chroab village, but he “lived there for quite a long time.” Further, he transplanted rice at Sala Kraham and grew cotton at Kang Va. He could not remember the exact time of either. Mr. Horl stated that he left Chroab Thmei village in 1976. Mr. Sam Onn asked whether all villagers from Roul Chruk village were evacuated, which the Civil Party confirmed. Roul Chruk village was located around five kilometers from Chroab Thmei village. Turning to the last topic, Mr. Sam Onn queried what Mr. Horl did before 1975. Mr. Horl answered that he was a rice farmer in his birth village.

National Co-Lawyer for Khieu Samphan Kong Sam Onn

At this point, the president announced that Mr. Horl could make a victim impact stated. Mr. Horl stated that

“I could survive the regime – lucky me. I endured hardship. I lost my relatives and my beloved ones. I am weak now as a result of the experience. I lost freedoms at the time. In particular, I lost my siblings and parents. At the time, whenever I felt sick, no relatives, no close relatives, or siblings, came to ask me or help me. No medicines were given to me when I was sick. No encouragement from anyone of my family members or relative. I was sick alone. I was alone at the time. I lost my relatives, immediate siblings, parents. I cannot mention all suffering I endured.”

As regards his questions, Mr. Horl stated that

“I would like to have two questions. Number one: regarding the Khmer Rouge regime, were leaders of the regime aware of the hardship endured by its people, by their people? And I received instructions or directions from Angkar, who was Angkar at the time? Was Angkar referred to one particular person, unit? I heard of Angkar instruction and directions, but I was not aware who Angkar was at the time.”

The president asked who the Civil Party directed the question to, to which the Civil Party answered that he wanted to put the question to the former leaders of the Democratic Kampuchea. Asked for clarification, Mr. Horl said he would like to put the questions to the two former leaders, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan. The president replied that the accused have exercised to remain silent. The chamber has not been informed that the accused have not waived their right to remain silent.

With this, the president adjourned the hearings. The chamber will continue hearings on August 26 at 9 am, when it will hold key document relating to Kampong Chhnang Airport, Trapeang Thma Damsite and the 1st of January Dam. With this, the president thanked the Civil Party and dismissed him.

[1] E3/5018 [2] E3/5018