Beginning of a New Segment: Genocide of the Cham

In today’s hearing, the new segment on the genocide of Cham started. Since the beginning of the tribunal, it is the first time that witnesses and Civil Parties are heard with regards to charges of genocide. During the first part of the hearings, Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé responded to last week’s key document presentations by the Co-Prosecution. In the second part, Cham witness It Sen gave his testimony. He told the court how he and his family was evacuated from his native village. After three years, he was sent back to his region of origin and after passing through his village, he was sent to Trea Village together with other Cham people. He told the Court how he witnessed killings in this village and escaped.

Reactions to Key Document Presentation

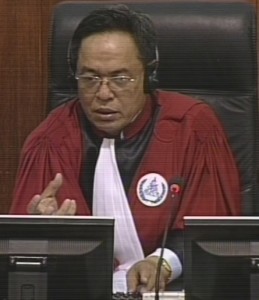

At the beginning of the session, Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn announced that at the beginning of today’s hearing, key document presentations would be held and the response by the Defense Teams would be heard. Upon conclusion of these presentations, the new segment on the treatment of Cham would start. He then stated that Judge You Ottara was absent due to personal reasons; the national reserve judge Thou Mony would replace him until he would be able to return. The Trial Chamber Greffier confirmed the presence of all other parties, with Nuon Chea following the proceedings from the holding cell. Today’s witness would be 2-TCW-813, while Civil Party TCCP-244 would be on reserve.

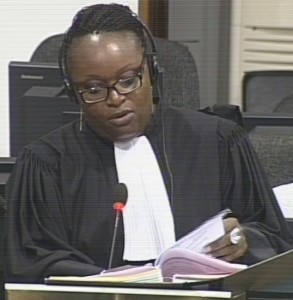

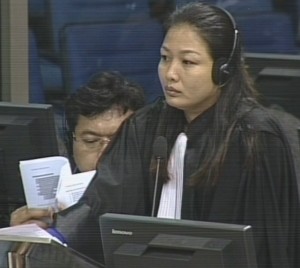

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

The Defense Counsel for Khieu Samphan Anta Guissé took the floor and began her observations on the presentations. She stated that “responding means making observations”, which would mean to give interpretations that may differ from the interpretation given by the Co-Prosecution. This would mean to stage adversarial debate. She would first give generic comments and then comment on specific elements in certain documents related to 1st January Dam, Kampong Chhnang Airfield, and Trapeang Thma Dam.

With regards to the generic comments, she stated that a significant proportion of the key documents presented were Written Records of Interviews of witnesses that have never appeared before the Court. She said that a criminal trial was mostly an oral trial, since the witness’s statement had to be assessed in terms of its probative value. An oral hearing would provide a better understanding of the sources the witness drew its information from and assess the witness’s credibility.

According to Ms. Guissé, presenting Written Records of Interviews as key documents was problematic, since they had weak probative value. She stated that “we have seen often here in front of the Court” that witnesses that appeared in front of the court corrected their applications and interviews and provided details that were not mentioned before. “This might be the most blatant example of this gap between written statements and what witnesses have said before this chamber.”

Ms. Guissé then gave the example of last week, September 1, recounting that Chao Lang went beyond explanations and provided a new testimony with regards to parts of his Civil Party Application. In fact, this person talked about his Filipino colleague, who was said to have had the role of a colonel responsible for explosives in the testimony and was actually a colleague of his father. “Sometimes, information is lost. Sometimes, when forms are processed by the ECCC […] there may be many possible errors here.” Ms. Guissé stated that these documents would consequently have low probative value in terms of reliability, and that questions needed to be asked to get to know the “true stories”.

She then gave the example of the testimony of September 02, where Tak Boeuy had testified. Ms. Guissé reminded the Court that during the hearings, the witness had clearly stated “I never said this” with regards to parts of his written statement[1]. She then reminded the Court that on April 3 a Civil Party had testified that he was actually not a Khmer Krom as indicated in his Civil Party Application.[2] This had prompted Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer to Marie Guiraud to state that “I’m obliged to acknowledge that this is a reality” and that “what matters is the oral statement of a Civil Party.” Ms. Guissé stated that the Chamber could hence not rely on these documents to sentence the accused.

Further, she indicated that the Chamber had given guidelines for disclosures[3] and had noted that there had been an issue of the probative value of a statement and the reliability of interviews without people testifying in front of the Court.

Ms. Guissé then reiterated the Defense’s position with regards to case 003 and 004: She said that on 18 July 2007, the Co-Prosecutors had filed an introductory submission and filed their final submissions on 16th August 2010. Thus, the Co-Prosecution had believed, according to Ms. Guissé, that the evidence was sufficient to sentence the accused. Ms. Guissé stated that during the proceedings, it has often been said that the Defense should have filed an appeal and that “it is too late now”. She admitted: “We did not react fast enough, it’s true.” However, she reminded the Court that the parties, simply because they did not respond to something, do not necessarily agree. She referred the Court to the general obligation of the Prosecutors with regards to the disclosure of documents coming from other cases. She recited a decision in the ICTY Martić case of January 19th 2006, paragraph 11, where it had been stated that the Chamber was the guardian of the substantive rights of the accused and had to strike the balance of different rights, and that questions of admissibility do not only arise when a party files an appeal. In this decision, it was stated that the Trial Chamber would intervene when the pieces of evidence would not adhere to the rules of admissibility.

President Nil Nonn

She recited this decision, because the documents of case 003 and 004 would also be affected by the reliability of the witness statements. Moreover, the audio records of these documents were not available anymore. She said that there had been instances where there were discrepancies between what had been said and what had been written. During key document hearings, the Defense would not have the opportunity to clarify whether there were any discrepancies. Without the witness testifying in front of the court, there was no opportunity to cross-check the information provided by the witness. Thus, having highlighted these points, the Khieu Samphan Defense Team maintained its position that Written Record of Interviews should not be admitted for key document hearings.

Moreover, if the parties were not able to obtain new information in advance, the chamber had to defend the rights of the accused. The Chamber might introduce new information, but “the timing is important”. There may be investigations that had not been conducted properly with regard to for example Trapeang Thma Dam. In such a situation, it should be born in mind that her client was put in custody based on this information. The parties should not be allowed to introduce new documents “to fill gaps.” She further argued that the Chamber had the opportunity to revisit its decision. If the rights of a party had been infringed, the Chamber had to “play its role as the custodian” of the accused rights.

Thus, when the Chamber found out that a document was not supposed to have been admitted, they could revisit their decision to admit the document. As regards the key documents for Trapeang Thma dam, it would be possible to revisit the Chamber’s decision according to Ms. Guissé. She requested the chamber to do.

She then proceeded to make observations to specific documents.

First, with regards to the article by François Ponchaud,[4] Ms. Guissé pointed to other extracts that had not been quoted by the Co-Prosecution. According to Ms. Guissé, these extracts showed that the aim of the Trapeang Thma dam was to produce sufficient rice. As Ms. Guissé pointed out, the Prosecution had argued that the construction of the dam was considered a battlefield. Ms. Guissé stated that it was indeed a war, but a war to grow rice. She then referred to the last page of the document,[5] where Ponchaud had stated that emphasis was laid on “strategic food crops”, such as bananas and soy beans.

The second document she made comments on was a Written Record of Interview.[6] The Co-Prosecution had stressed that there were problems in the technical training of technicians working at the dam site. Ms. Guissé highlighted questions and answer 45, in which the witness had been asked whether the techniques had been scientific. The witness had answered that he believed the technique was good at the time, and even ahead of the time. With regards to the plan of the 1st January Dam, Ms. Guissé pointed out question 54, where the witness had been asked whether he saw the “master plan” for the dam, which the witness had denied. He had stated that he had only seen the plans of the water gates. The Co-Prosecution had challenged the feasibility of the master plan, but had left out a relevant part of the interview.

Another document she referred to was the Written Record of Interview of Ke Pich Vannak, son of Ke Pauk, from which the Co-Prosecutors had quoted the lack of medicine at the site.[7] However, they had not quoted what the witness had stated later. Ms. Guissé quoted the witness, who had stated that Ieng Tirith had issued that traditional medicine be boiled to obtain black-colored medicine. He had stated that he was not sure whether Ieng Tirith had known about deaths of people related to a lack of medicine, but that Ieng Tirith said that research was done on traditional medicine so that it could be used to treat sick people. Ms. Guissé stated that this medicine might have been insufficient, but that it was not a strategy to kill people.

Referring to Written Record of Interview of another witness[8], Ms. Guissé pointed out that the witness had stated that there were district chiefs, village chiefs and sub-district chiefs, but that he did not know who the sub-district chiefs received information from. Thus, according to Ms. Guissé, most of the witnesses spoke at length about cadres, while actually not knowing where they received information and instructions from.

She further highlighted that in the English version of the biography of Ke Pauk,[9] pages were missing. Thus, “the Khieu Samphan Defense Team is of the opinion that this document had very low probative value.” An inquiry should be made about the missing pages.

Ms. Guissé then referred to the media articles related to visits of foreign delegations at the dam.[10] Ms. Guissé noted that it should be born in mind that Khieu Samphan had not been featured as one of the persons who accompanied the delegations to the dam. Also Becker had said in front of the Court that she did not see Khieu Samphan during her visit.

As for written statements of Civil Parties, “we have to regard it with a pinch of salt” with regards to their probative value.

Ms. Guissé then referred to the remarks that had arisen related to Kampong Chhnang airfield. The documents the Co-Prosecution had referred to last week were military documents,[11] with the help of which the Prosecution had proved that Khieu Samphan had been informed of the building of Kampong Chhnang airport. However, in the view of Ms. Guissé, being informed of a plan did indicate the person’s willingness to comply with the plan.

Moreover, the Co-Prosecution had presented documents related to chain of military command that mentioned different cadres had been mentioned.[12] It should be born in mind that people often did not know the leaders and easily might have confused the names.

As regards meeting minutes,[13] the list of attendees was not always available. It was also not known what was related to Kampong Chhnang. These documents should not be used to proof that there was any plan to mistreat the soldiers who were at the Kampong Chhnang construction worksite. Most of these documents were military document. The Chamber had ruled earlier that it was convinced that Khieu Samphan did not hold any military decision power. She further stressed that these minutes of meetings demonstrated that the issues of food and rice were being taken into consideration. This point was important with regards to why these dams were built.

Ms. Guissé then referred to document E3/13, which were the minutes of a meeting of the standing committee.[14] In this document it had been stated that rice should be given to workers two to three times per day and a liter of fish sauce per month. She further quoted: “What is important it to solve the production issues”, “we have to grow many vegetables and give more energy to the movement” and that the living conditions of the workers had to be monitored.

At this point, Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde interjected and corrected the document number, which was E3/804 and not E3/13.

Ms. Guissé thanked Mr. de Wilde for the correction at turned back to document E3/13. She said that on the last page, statistics about the food production were indicated. Turning back to document E3/804,[15] she said that the focus was set on harvesting and that lack of water needed to be solved. A sufficient number of seeds, according to this document, needed to be set aside. Moreover, this document showed that there were constant concerns with regards to what kind of rice could be harvested and which rations could be given to the forced.[16]

As regards E3/1114, Ms. Guissé stressed that this was a military document.

She then proceeded to document E3/849,[17] which showed that division 310 and 450 were in Kampong Chhnang in March 1977 and considered part of the revolutionary army of Democratic Kampuchea.

Another document was E3/5263, which was a Written Record of Interview of Sring Thi, who spoke about a security center called S-22. However, this security center was not included in the closing brief. Thus, this part of the interview could not be seen as being included in the scope of the trial, since this would infringe her client’s right to defend himself.

The next document Ms. Guissé referred to were the two Written Records of Interview of Chouk Rin,[18] who was heard during case 002/01 and who said that Khieu Samphan held no military responsibility. It was “a pity that this person was not asked to speak in front of the chamber here”. However, referring to one of his interview,[19], Ms. Guissé stated that the Prosecution had not mentioned that the witness had been asked to clarify how he had received orders to go to the East Zone. This witness had answered that they had received orders by telegrams and verbal orders in a special military meeting in Phnom Penh, which was attended by 40 to 50 people. Thus, there were separate meetings for the military and civilians. This was important to consider, since the Chamber had held that Khieu Samphan held no military duties.

Ms. Guissé then pointed out that in the Written Record of Interview of Sin Sot[20] the witness had stated that he never saw any leader at Kampong Chhnang airfield and did not know anyone. However, he saw hundreds of Chinese people in delegations. Thus, he had been talking about Chinese people overseeing the work at Kampong Chhnang worksite.

As her last point related to Kampong Chhang airport, she stated that the Co-Prosecution referred to crimes that occurred later than the period that was in the scope of the trial, but had asked the Chamber to take these executions into account nevertheless. Furthermore, the Co-Prosecution had referred to one part of Khoem Samhuon’s interview,[21] but had not mentioned that this person had stated at a later point that the person never saw anyone dying at the Kampong Chhnang site and that workers were sent to Kampong Chhnang hospital. Ms. Guissé the cited William Smith, who had said that “The Co-Prosecution is aware of the fact that the accused are not being charged with these execution crimes (…) However, we’re asking the Chamber to take into account this evidence in order to see whether these workers were persecuted at the worksite or not.”

Ms. Guissé stated that she saw a legal problem there, since these were crimes that the Chamber was not ceased of. In Ms. Guissé’s view, taking these elements into account without having heard the witness to proof a crime of persecution was “a particularly poorly founded request”, in particular since the Co-Prosecution did not cite the passage that stated that the witness did not see anyone die at the worksite.

At this point, Mr. de Wilde interjected. He clarified that paragraph 398 of the Closing Order mentioned massacres that occurred after January 1979 and that the judge therefore considered them relevant. These were not under the scope of the trial, but were important to assess the intentions that leader had.

Ms. Guissé replied that if they agreed that this was not under the scope of the trial and if there was no means to cross check this information, she could not understand how these documents could be included as key documents.

Response to Trapeang Thma Key Document Presentation

After the break, Ms. Guissé continued her responses to the presentation and turned to Trapeang Thma dam. She pointed to document that the by the Co-Prosecution presented document E3/178 indicated the damage of crops.[22] Due to the drought, the “general offenses” could not be launched. This passage highlighted, according to Ms. Guissé, the problems faced by the leaders to provide sufficient food to the workers. Thus, the problems by the people with regards to food shortages could not be regarded as a strategy to famish the workers, as the Co-Prosecution had done according to Ms. Guissé.

She then pointed to another passage,[23] which showed in Ms. Guissé’s view that whenever there was a food shortage due to drought, there was an internal management system to organize supply food from one place to another. Hence, there were “adjustments in solidarity with other zones.”

Another passage showed that leaders were concerns about food rations in Region 5.[24] With regards to a report by Nhim to Angkar Office 870,[25] Ms. Guissé stated that this report pointed out that there had to be sufficient food supplies. The issue of food shortages and living conditions of the people were under the responsibility of the commanders. These were “working hard” to resolve the issues. These efforts, according to Ms. Guissé, had to be taken into account, since it showed that the water basins were built under these circumstances to resolve the problems.

The next document she turned to was a document that Sector 5 faced food shortages.[26] To Ms. Guissé, this put the irrigation into context with the drought to make it possible to harvest rice.

Turning to her last point regarding Trapeang Thma dam, she stated that the documents presented by the Prosecutions were to a large part Written Record of Interviews coming from another case. She admitted that “maybe we were not reactive enough” by not systematically objecting to the introduction of documents coming from cases 003 and 004 or that were not by witnesses that were deceased and who will not testify in front of the court. She stated that the necessary decisions should nevertheless be made, that is to decide that they had “very little probative value” and should be cast aside from a ruling. With this, Ms. Guissé finished her response to the Co-Prosecution’s key document presentation.

First Witness Testifying on Genocide of Cham

The President announced that this concluded the key document hearings. The President ordered the court officer to usher witness TCW-813 in, who would provide his testimony with regards to the treatment of Cham.

The Muslim witness It Sen, father of five sons and one daughter, could not recall his date of birth, but stated that he was 63 years old. He was born in Ampil Village, Kampong Cham province, is now living in Ampil village, Kampong Cham province and is working at a Cashew nut farm.

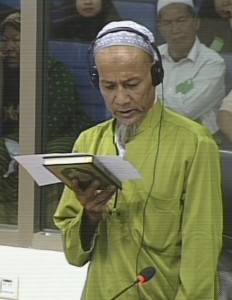

Witness It Sem was taking an oath

The witness was then sworn in according to his religion. He put the right hand on the Qur’an and “I would like to answer only the truth from what I witnessed, heard, know and remember. In the name of an Islamic believer, who has only Allah as God, Muhammed as Allah’s messenger, and the holy Qur’an as the guideline for me to follow, I would like to swear in front of the holy Qur’an: Wallahi Billahi, which verifies that all that I am going to say is true.”

The President then informed the witness about his rights and obligations, including the right against self-incrimination and the obligation to respond to questions by the bench or relevant parties. Mr. Sen was interviewed twice and had read the written records of these interviews again. He confirmed that these written records reflected what he had said. The President then gave the floor to the Co-Prosecution.

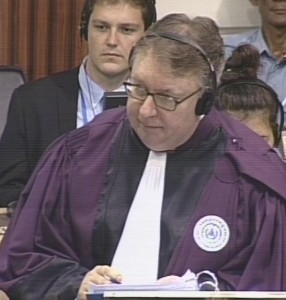

Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak took the floor. He started his line of questioning by asking background questions about where the witness grew up and “what it meant to be a Cham”.

In 1973, Mr. Sen was living in Ampil Village, which was a Cham village adjacent to a Khmer Village called Peh. To his recollection, more Cham were living in this village and adjacent villages than Khmer people. However, he could not recall the exact number of Cham families living there.

Pointing out that this witness is the first one to testify in this segment, Mr. Lysak then asked what it meant to be a Cham, to which Mr. Sen answered that the Cham practice the Qur’an and have their own language. Some Cham follow the traditional practice with regards to clothes, while some wear more modern clothes. The Khmer Rouge forced the Cham women to cut their hair short, and they were not allowed to practice their prayer.

Mr. Lysak asked whether there were other distinct features of the Cham culture aside from clothing that would identify them as being Cham. Mr. Sen replied that beside the costumes, you could identify a person as a Muslim when he or she goes to the mosque to pray and that they refrain from smoking for a certain period of time during the year. Mr. Lysak asked whether Cham had a specific language or dialect when speaking Khmer. Mr. Sen answered that when the Khmer Rouge took power, they forced them to speak Khmer and not their own language.

Asked about names, Mr. Sen stated that Cham named their children differently than Khmer people. In the early 1970s, Cham were living mostly in Kampong Cham province. There were many Cham lived along the Mekong River.

In his district, there was one Khmer village, and adjacent to this two Cham villages.

Mr. Lysak read out an excerpt of a book by Ben Kiernan,[27] where Ben Kiernan stated that Cham numbered “well over 20,000” in the North of Kampong Cham (in Krouch Chhmar), where they were in the majority compared to Khmer. Mr. Lysak then asked whether the witness remembered the number of people living in his district at the time. Mr. Sen could not shed much light on this matter, and after the Defense Counsels for Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan Victor Koppe and Kong Sam Onn interjected, the President adjourned the hearing for the lunch break.

Restrictions on Religious Practices

After the morning session, the President announced that the witness found it difficult to reply to long questions. The witness might have difficulties to understand questions in the Khmer language. Thus, the Co-Prosecution should ask simple questions.

Mr. Lysak took up his line of questioning and asked him about the witness’s family in his home village. Mr. Sen replied that he was married in 1973 and had two children. There was a big mosque in Ampil village, which remained until today. Asked about the leaders in the village, Mr. Sen recounted that Seng (13:35) was the leader of the village at the time. There were hakims[28] in his village, but he did not know them very well. He did not know what happened to them when the Khmer Rouge arrived and also did not know what their positions were at the time.

After the Khmer Rouge took over power, halls were built for “all of us”, and they had to eat collectively. The village was under “strict control of the Khmer Rouge at the time.” When the Khmer Rouge arrived, Muslims were not allowed to practice Islam anymore: “no more prayers and no more religion.” They could not “sit in groups and discuss” anymore.

Deputy Co-Prosecutor Dale Lysak

Mr. Sen stated that he only knew that Mr. Seng was responsible for the village. He “was strict and did not allow them to practice” their religion anymore. Asked what happened to the Qur’ans in their village when the Khmer Rouge arrived, Mr. Sen stated that “they were collected from houses and burned down.” Further, “there was a rebellion in the villages to fight against these acts.” With regards to the burning of the Qur’ans, security guards collected them. “They received instructions from the upper echelons.” All Muslim women were called into the mosque and assigned to do agricultural farming.

Mr. Lysak then asked about the importance of prayer in their religion. Mr. Sen replied that no one dared to practice the religion. “If one dared to resist the orders, they would be arrested and sent away.” They were prohibited from talking freely. Neither were they allowed to speak the Cham language. “Only the Khmer language was allowed.” If someone was caught speaking the Cham language, they “would be taken away and killed.” After three years, they were allowed to “speak our language”. They were given pork to eat.

Mr. Lysak inquired about the cutting of the hair. Mr. Sen replied that according to the Qur’an, Muslim women were required to have long hair. However, during the Khmer Rouge time, they had to cut their hair short. “This is the difference between the religions.” However, “it was okay, because after a while, our hair grew long.” The order to cut their hair went through the village chiefs. Otherwise “we would be considered opposing Angkar.” When the Khmer Rouge took power, they were allowed to wear traditional clothing. Asked whether there was any point in time that they were instructed to wear black clothes, Mr. Sen replied that “they had the same black clothes to wear, after we were given such clothes.”

Turning back to the rebellion at Koh Phal, Mr. Lysak inquired about what happened back then. Mr. Sen replied that the people in Ampil were not allowed to cross to Kho Phal. They were afraid that “we in our village would help Cham people in Kho Phal.” Kho Phal was around two kilometers away from his village. “There was artillery used by [the Khmer Rouge].” He further recounted that “we had to stay calmly in our village.” After the rebellion in 1975, all Muslim people were evacuated from Koh Phal, which was an island in the middle of the Mekong River. His elder sibling was living on the island. He/she[29] was his older sister-/brother-in-law. This person was living on the island and fled to Ampil village and told Mr. Sen about the rebellion. His in-law told the witness that “those who opposed Angkar were smashed. They were shut or their throats were slit.” Most Muslim men were killed and only Muslim women remained.

Mr. Lysak asked whether this event took place during Ramadan, which Mr. Sen denied. However, he could not remember the month in which it took place. The rebellion took place because they were not allowed to practice their religion. “They brought in the troops to curb the rebellion.” The witness confirmed that they were not allowed to practice Ramadan. “Because of this, there was a rebellion happening at the time.”

Evacuation to Other Villages

Mr. Lysak then asked what happened to the witness’s family after the rebellion. Mr. Sen replied that his family, together with the villagers, was evacuated. Some were sent to Battambang province, some to Stung Trang District[30] and some to Kratie. His family and he were sent to Kratie. Some people could stay in the village, while “half of the villagers were transferred to different places.” The district committee and people at the commune level, including the security guards, “ordered all of us to leave the village.” They were instructed to board a ship to Battambang. His family was sent to Sangkae, before being transferred back to Kratie after 20 days. Sangkae was located to Stung Trang district. It was located on the other side of Krouch Chhmar.

Mr. Lysak asked whether it was correct that they were first sent to Stung Trang District, which Mr. Sen confirmed. The witness could not recall the exact number of people. “There were around 100 boats loaded going to Stung Trang District.” When they arrived, they were transferred to other regions. “There were not enough trucks for those people leaving the boats.” There were also people from other villages and not only Ampil village. There were only Cham people when they were moved from Kampong Cham. When being asked about the reasons for the evacuation that they were being told, Mr. Sen recalled that the Khmer Rouge said that “the villages were crowed”, and that they would be sent to Battambang which provided more space.

Next, they were sent to Preak Anchy, located in Krouch Chhmar district. In this village, they were placed into various houses belonging to Khmer people.

Mr. Lysak then asked whether anyone ever explained why they were moved to Steung Trang for 20 days, and then moved back to Krouch Chhmar. The witness replied that he had been told that there were too many people who moved to Battambang, and that this was the reason why they were sent back. They stayed there for around three years. When the “attack occurred in the East Zone, we were instructed to return to our respective villages.”

Asked about the treatment at Preak Anchy, “they didn’t do anything to us. […] he didn’t chase us away.” There, he was assigned to water the rice fields behind Preak Anchy village. During his time there, they were not allowed to practice their religion. When they did not want to eat pork, “they mixed pork meat into the beef mixed. And we didn’t know about that. Every Cham was forced to eat pork. Some of us could not take it, so they vomited after they ate.”

Turning to his next topic, Mr. Lysak asked whether the local cadres were replaced by other cadres at some point. Mr. Sen replied that “we were arrested when we returned to Ampil village.” Some of them were arrested and killed. Mr. Lysak clarified that he was referring to the cadres which might have been replaced by the Southwest Zone cadres. Mr. Sen replied that there was no replacement. “Actually, the Southwest Zone was in full control” of the village when they arrived. “That happened in every village.” Before this, they fought against forces from the East Zone. After this, “they took control”. This took place around mid-1978, three years after the evacuation. This was the time when the extensive killings took place.

“A fortnight” after having returned to Ampil village, they were sent further to Trea Village. It was the village chief who was a Southwest Zone cadre told them to return to Ampil. When they arrived there, they were told that “Ampil village was crowded” and located further to Trea.

Mr. Lysak read an excerpt of the interview that Mr. Sen gave to Ysa Osman:[31] “In 1978, the cadres of the Central Zone [Southwest Zone as corrected later in the OCIJ Interview] came in and set up a new administrative structure. The people welcomed this, because the cadres claimed to be uncorrupted.” They announced that the people could turn back to their home village. “this announcement gave us hope again for the Cham race.” When asked who said this, Mr. Sen replied that he could not remember. The village and unit chiefs told them that they could return.

Mr. Lysak then asked why he “had lost hope” for the Cham people. Mr. Sen replied: “It was their policy to seriously mistreat us. We were absolutely prohibited from worshipping.” At the slightest mistake, they would be taken away and killed. “Even the village chiefs […] were arrested and killed after the Southwest Zone cadres arrived. They kept disappearing one after another.”

Mr. Lysak then inquired what the witness observed in 1978 when he returned for a brief moment of time and how many Cham families were left there. Mr. Sen replied that “there were quite a number of Cham remaining in that village”. Moreover, some Khmer families were living with the Cham people there.

This prompted Mr. Lysak to read out an excerpt of the interview he had given to Mr. Ysa.[32] in which he had stated that there “only ten Cham families” out of the 100 that were there before. Mr. Sen replied that this was not correct and that there were more than ten families living there. “It could be between 20, 30 or 40 families still living there.”

Mr. Lysak then asked what happened on the way from Ampil to Trea village.

everything had to be placed on an oxcart. We believed that we were sent to Trea village. And when we arrived in Trea village, we didn’t even have any rice to eat yet. And we saw the Trea Village was full of soldiers.

According to Mr. Sen, there were 20 oxcarts. “the 20 oxcarts were full of members of 30 families.” He did not see any other families moving. “I saw lots of people in Krauch Mar village. We were all destined to be killed. And when we arrived in Trea village, the soldiers ordered us to offload our belongings and place them in a mosque there.”

Mr. Lysak asked to clarify whether there was only the 30 families that were in Trea village,or whether other families were other there. “There were other Cham families from Suoy Village.” More people had been sent to Trea village before they had arrived. Around 15-20 families were from Suoy village.

Mr. Lysak then inquired whether he could remember “meeting an elderly woman” on his way to Trea Village. Mr. Sen replied that Cham people asked him where they were heading on their way to Trea Village. They were told that some “Cham people were blindfolded and sent to the river bank.” Some Cham women cried and told them that the blindfolding took place almost every day. They were told this when they were almost at Trea Village.

Killings at Trea Village

To travel from Ampil village to Trea Village took them from the morning to the late afternoon.

Mr. Lysak then inquired what Comrade Seng was doing while they were travelling from Ampil Village to TRea. Mr. Seng replied that “he had overall responsibility over Krouch Chhmar District.” And that he was on the Krouch Chhmar District committee.

Mr Sen recalled that he was travelling with his wife, his child, and his mother-in-law. His child “could speak at the time.” The child was perhaps two or three years old. Mr. Sen then testified that they were separated after their arrival. The girls who were of full-age were not allowed to stay with their parents at the time. These unmarried girls were put into a different group. “At the time, the men were allowed to go to have porridge. Women were told to stay at one particular place. It was during the time when the sun was already down”. Asked about the number of men who were told to go to a house to eat porridge, he stated that around 40 men “climbed up onto a house”. His wife was staying in a mosque. “The men were told to go the river front and we were told to stand in line. They pointed the guns at our necks.” Recounting the events, “it was that time that I parted from my wife and toddler.” He did not see his wife and child after this again. He was beaten and kicked:

“they used the rubber sandals to beat our heads. Some of us fell down on the ground.” They said that “these people were Muslims.” If we stated that we were Khmer, they would repeatedly kick us. We were afraid. That is why we said that we were Khmer.”

Mr. Lysak turned back to their arrival in Trea Village and asked what the soldiers the witness had mentioned earlier were doing there. Mr. Sen said “the soldiers were killing people. And ropes were used to tie people. We were put on a boat, and the boat went into the middle of the river. I was staying in that house. And they came to collect some of us from time to time. I was on the house and we, some of us, were weeping and crying at the time.”

At this point, the President interjected and adjourned the hearing for a short recess.

After the break, the President gave the floor to the Co-Prosecution.

Mr. Lysak took the questioning back to the time where the witness had been brought to a house by the river with 40 men. He asked how many cadres were at that house with them. Mr. Sen replied that he “did not count them at the time.” There were many Khmer Rouge soldiers. “We were sleeping on the house and there were Khmer Rouge soldiers below the house.” There were about 20 houses. Asked whether these Khmer Rouge soldiers had guns, Mr. Sen replied that “they were all armed.” Mr. Lysak then asked whether when they were at the house was the moment when they were asked whether they were Cham or Khmer. He replied that “they asked us when all of us were tied up.” They were beaten until “they were satisfied with their acts.”

It was about 7 pm when they “were told to climb up the house; doors and windows were locked.” There were about ten who guarded them, sleeping in hammocks. Some of the Cham said that they were Khmer. The Khmer Rouge beat them and when they fell down onto the ground, they were grabbed by their hair. There were no other questions than whether they were Cham or Khmer. In that house, “everyone was tied up.” When he was at that house, he also saw other people in other houses. The houses were close to each other and “full of Cham people.” Asked how he knew that the people in the other houses were also Cham, he said that they “talked one to another”. He did not know where these Cham people had been arrested.

Mr. Lysak then turned to the morning after they had been detained in the houses. Mr. Sen replied that “nothing happened the next morning. We were in that house for one day and one night. And the military man told us that we would be given porridge to eat. We were waiting until the evening.” However, in the evening there was no porridge either. “We had no water to drink and no meal to eat.” Mr. Lysak asked to clarify whether he understood correctly that they were held at the house for a day without food or water after having been detained for the night. Mr. Sen confirmed this. “The day after, we were still tied up, and we were taken to the river front. At that time, I untied the rope and fled the house through the back door. During the second night, there were no soldiers behind the house.”

Other Cham groups that were at the village were taken to the river front. “All Cham were taken out to the big pit. I saw the iron bar with the size of my lower arm located at the pit.”

Mr. Lysak then asked whether Mr. Sen saw people being taken into the river. Mr. Sen recounted that “After I could manage to flee the house, I was staying secretly close to the route where the soldiers were taken Cham people to the river front.”

He recounted:

No screaming, no crying. It was quiet. And after Cham people in one house had been collected by those soldiers, the soldiers would go to take Cham people from another house and they did this until all people left those houses. I was secretly staying in the bushes, the morning glory bushes, and I watched the incidents until they completed the killing.

Mr. Lysak asked whether the witness had seen the killing of these people and, if so, how the soldiers were killing the people.

Mr. Sen replied that:

I saw very clearly that Cham people were being walked away to the river. They blindfolded Cham people and they tied up Cham people. After Cham people reached the river, they were told to board the motorboat. They drove those Cham people to the river and sank the boat into the river. They did this until they completely collected people from the houses. At night time, I could not see what happened at those places.

This prompted Mr. Lysak to read an excerpt of his interview with Ysa Osman[33]

Mr. Sen had stated in his interview that the prisoners were taken to a boat and undressed by the Khmer Rouge “to the shorts”. The prisoners were tied towards the boat in a row. Then, the Khmer Rouge drove the boat to the middle of the river, where they untied the rope from the boat and drove back to the river front to repeat the procedure.

Mr. Lysak asked whether he saw people being dragged into the river saw this when he was still at the house, or after he had escaped from the house. Mr. Sen stated that this is what he saw during the day. When seeing this, “I was crying together with other Cham people and I could manage to escape the house one day.” There was a pile of clothes.

Mr. Lysak then asked how far the house was away from the river. Mr. Sen replied that it was around 50 meters away from the river. “I could see what happened very clearly (…), I could look through the crack of the wall.”

Asked to describe the house, Mr. Sen stated that “it was an old house. It was eleven meters long and six meters wide. (…) It was a traditional house. It was elevated from the ground.” However, the elevation was not high, since they could reach the ground with their hands.

Mr. Lysak asked how often Mr. Sen saw people being taken out and drown in the river. Mr. Sen replied that

It happened from the morning until the evening. It started from 7 am in the morning. I did not know how many trips they came to collected people. It happened repeatedly from the morning until the evening (…). I was sitting in the house watching what was happening. I was crying, I was weeping. I was thinking that my fate would be in the same way. They were walking past my house.

Mr. Lysak further inquired how Mr. Sen managed to escape from the house. The witness replied that he fled from the house and hid in the bushes. “I was crawling towards the river. I was crawling and terrified at the time.” When reaching the river front, he could see “piles of clothes.” At that time he had a water container and filled it up with water from the river. “I swam across the river.” Mr. Lysak asked how exactly Mr. Sen was able to escape from the house before swimming across the river. He replied that “at the time, they were tying up the Cham people. The house was eleven meters long, and while they were tying up the Cham people in front, I fled the house from the back door. They did not know at the time.” There had been heavy rain during the night, and the sky “was really dark. Even with a lantern they could not see I was escaping.” Mr. Lysak then asked whether he left through a door or “through a plank on the floor.” Mr. Sen replied that a plank was loose, and “it was just big enough for my body physically to get out of the house. No one was aware that I was able to go through that whole after I removed the plant. The soldiers were in front tying up the knots on the people.”

Mr. Lysak asked whether understood correctly that he escaped at the time when the other people were taken out, which Mr. Sen confirmed. He stated that he could escape when around half of the people had been taken away already. Around ten people had been taken out of the house, while ten were still remaining in the house.

Mr. Lysak inquired what the size of the pile of clothes and where exactly it was located. Mr. Sen replied that it was during the night, which was why he could not see but only feel it. “People were stripped of their clothes near the water front. […] I did not know what happened to the owners of the clothes.” The pile was around two meters wide and half a meter high. “It could be up to my waist.”

Mr. Lysak then inquired where Mr. Sen swam when crossing the river. He reached the other side at Preak Anchy. He had a cousin there, which is where he went. It was not yet dawn, and since he had not had any food for two days, he “ate a raw corn.”

Mr. Lysak then asked whether Mr. Sen saw any of those people who were taken to Trea village with him afterwards.

He said that he went by himself and hid himself in the house of his older sibling. His older sibling shared the gruel. The witness replied that he never saw any of those people again.

Turning to his last question, Mr. Lysak queried how many of his family members died during the Khmer Rouge Regime. Mr. Sen replied that he lost two of his older siblings, his two elder brothers. There were only three boys, including himself, but his other two brothers had been killed. He never saw his wife and his child again. He did not know how they died.

Back to Forced Movement

At this point, national Deputy Co-Prosecutor Sen Leang took the floor and asked whether he saw any Cham person being forced to marry, which Mr. Sen denied. Mr. Leang then asked how many villagers were resettled to Trea village. Mr. Sen replied that it were around 20 families from Ampil and around 20 from Soy village.

He then asked whether he made any requests to the village chief upon his return in Ampil Village. Mr. Sen replied that they were not allowed to stay in Ampil Village. Mr. Sen told the village chief that he did not want to go. “I knew that we would be killed” when arriving in Trea Village. However, there was no alternative. He knew that they would be killed at Trea Village, because a group of people had been sent to Ampil Village, being told that they would have to build houses, but these people never returned. This happened with another group of people as well.

In total, there were around 40 families from these two villages. “I saw many men when I was sent there.” He did not see any guards on the road. “We were asked to make our journey by ourselves.” Comrade Seng monitored them on his motorbike when travelling between the two villages. Mr. Sen did not see Seng carrying any weapon. Mr. Leang then asked why he did not flee to another village if he knew that they would be killed at Trea village and there were no security guards.

Mr. Sen replied that when they almost reached Trea Village, they did not want to go any further. He stated: “we didn’t know where to go. If we were to go to the forest with the oxcarts we would not make it. (…) It was too late to return or go back.” Around half an hour before the village, they stopped for approximately half an hour. “We did not know what to do. We knew we would be taken away and killed” when entering the village. However, they could also not turn back. “It was too late.”

Civil Party Lawyer Ty Srinna took the floor. She asked about the living conditions and food rations at Preak Anchy village. He answered that “the situation was extremely difficult”. They had three kilograms of rice for a family and cooked gruel. Pork meat was mixed with the rest of the food. “However, some of us refused to eat.” They were given grains of salt instead. Ms. Srinna then asked what effect it had when they were forced to eat pork. He answered that some threw up afterwards and begged to have salt instead of pork. Sometimes they hid salt that they could eat instead of pork.

Civil Party Lawyer Ty Srinna

Ms. Srinna then asked what would happen to those who were forced to eat meat. He replied that “Allah prohibited us to eat dog or pork meat.”

Mr. Sen stated that the holy Qur’an instructed Muslims to pray. They pray by worshipping the holy Qur’an. Not every Muslim person practices pray. However, ordinary Muslims have to pray.

She then turned to the time at Trea Village and whether they committed any mistakes before being sent there. Mr. Sen stated that they had not committed any mistakes.

Ms. Srinna then asked whether they were questioned about anything else except their ethnicity, which Mr. Sen denied. “They knew that we were all pure Cham people. However, we were afraid that they would beat us when we told them that we were Cham.”

Cham Muslims in Kho village, Kampong Cham district, Kampong Cham Province. This photo was donated to DC-CAM around 2010. Posed in the photo is Cham Muslim leaders from Ko village and other Cham villages nearby. Most of these people in the photo were executed during the Khmer Rouge. The village was predominantly Cham, but after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime it was densely populated by other ethnicities. A small number of survivors are scattered in many places. A few families now reside in Km 8, Phnom Penh City.

Ms. Srinna then asked whether he ever returned to Trea Village after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime, which Mr. Sen denied. “From what people said, we all know there was only one large pit there with many iron bars scattered nearby. But personally, I never returned again.” Ms. Srinna then asked whether he was aware of the killing of Cham women. He answered that the wives, the unmarried women, and husbands were killed separately. Cham were killed in three separate groups.

Ms. Srinna asked whether he ever heard about a woman who was asked to lay down on a plank and whose throat was cut afterwards. Mr. Sen replied that he heard the killing, but did not see it.

At this point, the President adjourned and stated that the hearings would resume at 9 am on Tuesday, September 08 2015. The next person to testify would be Civil Party TCCP-244.

[1]E3/331 [2] E1/288.1. She was referring to the testimony of Ri Pov. [3] E3/19.14.2 [4] E3/2412, at 00812343 (KH) 00598519 (ENG) [5] 00410772 (FR), 00598525 (ENG) 00410772 (KH) [6] E3/5513 [7] E3/602 [8] E3/9349, at 00277537 (FR), 00239922 (KH) 00244157 (ENG), [9] E3/2782 and E3/2783, at 00089716 (ENG). [10] E3/84 and E3/86. [11] For example E3/182. [12] E3/229, at 00334948 (FR), 00000713-14 (KH) 00182625 (ENG); E3/222, at 00323891 (FR) 0000784 (KH), 000182665-66 (ENG) [13] E.g. E3/236. [14] E3/13, at 0023323892 (FR) 0052416 (KH) 00183994 (ENG) [15] E3/804, at 00386209 (FR), 0008482-84 (KH) 00233719-20 (ENG) [16] E3/804, at 00386210 (FR) , same pages in Eng and Khmer as before [17] E3/849, at 00183956 (ENG) number two and 3, no French translation [18] E3/362 and E3/361: [19] E3/361, at 00268884 (FR), 00194467 (KH), 00766453 (ENG). [20] E3/5276, at 00339922 (FR), 00282954 (KH) 00287356 (ENG). [21] E3/3962; interview of 00355878 (FR) 00287540 (KH) 00293369 (ENG) [22] E3/178, at 00623317 (FR), 00275596 (KH), 00342719-20 (ENG). [23] E3/178, at 00623318-19 (FR), 00275597 (KH), 00342721 (ENG) [24] E3/179, at 00236772 (FR), 00008501 (KH), 00183016 (ENG) [25] E3/950, at 00296222 (FR), 00021044 (FR) 00185216 (ENG). [26] E3/863, at 006232408 (FR) 000076286 (KH) 00321961 (ENG). [27] E3/1593, at 00637755 (KH) 00678632 (ENG), 00639022 (FR). [28] Hakims are leaders or governors in Muslim countries and cultures. [29] In the Khmer language, the gender for the word sibling is not defined. [30] Stung Trang District is located in Kampong Cham and should not be confused with the region Stung Treng in the North of Cambodia [31] E3/9334, at 00204435 (KH) 00204442 (ENG), 00274723 (FR). [32] E3/9334, at 00204435 (KH), 00204442 (ENG), 00274723 (FR). [33] E3/9334, at 00204436-37 (KH), 00204442-43 (ENG); 00274724-25 (FR),.