“Each of us would be taken one by one to be killed” – the Vietnamese Segment Continues

Today’s hearing started with the remainder of witness Sao Sak, who gave evidence about the treatment of the Vietnamese people in her village. Next, Civil Party Choeung Yaing Chaet took the stand in the court room and recounted how he and his family were taken away to be killed when he was 13 or 14 years old. He survived the killing and fled to another village, before he was taken to Vietnam.

Villagers

At the beginning of the session, the Trial Chamber Greffier confirmed the presence of all parties, with Nuon Chea following the proceedings from the holding cell. First, witness Sao Sak would be heard and Civil Party 2-TCCP-241was on the reserve.presu

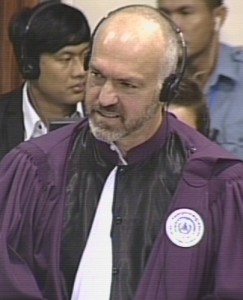

The floor was then handed over to the Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian.

Mr. Koumjian asked whether she knew what happened to Khun Mon’s wife’s mother (Chea Hoa) and her siblings (Ly Ty Thay). Ms. Sak confirmed that she knew the couple, but she did not know what happened to the family, since they moved to another commune. Since their separation, she “never saw her visit the village.” Mr. Koumjian referred to an article by Khun Mon, who had stated that he understood the arrest of his wife only later – namely that anyone who was related by blood to Vietnamese would be killed. Several members of his family had been killed.[1] Mr. Koumjian asked whether she would have anything to add to this. Ms. Sak replied that she only knew the father, while the children were taken away and killed. She did not know the fate of Muon Hua.

Referring to another statement, Mr. Koumjian asked whether she knew someone called Ta Prunh, which she denied.[2] Neither did she know the person Om Lach Ni who was mentioned on the next page.

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian

Mr. Koumjian then inquired about Yim Muoy, whose mother was Hai and who was of mixed ethnicity.[3] Mr. Koumjian asked whether she knew Yim Muoy. Ms. Sak confirmed knowing this person. Her children were living in Phnom Penh, but she passed away later. Mr. Koumjian then wanted to know whether she knew Muoy’s relatives Tieng (younger sister), Hou (younger sister). She stated that they separated in 1979, but did not know what happened to the rest of the family. “I only knew that Hou was killed.” Mr. Koumjian said that Yim Muoy had stated in her interview that her younger brother, younger sisters, cousins, and mother were killed. Ms. Sak replied that she did not know. “I lived in a different village.”

Ms. Sak did not know Mom Choeuy or his wife Neang Phan.

As regards a midwife in Anlong Trea who was called Yeay Dak and her child Ba, Ms. Sak recounted that “She mostly saved villagers in Anlong Trea and other villages through her midwifery practice. […] However, she was taken away and killed. Only later on we learned that she was taken away.” This person was originally Vietnamese. She saved people regardless of their ethnicity.

Turning to the next topic, Mr. Koumjian inquired whether she knew about cadres who replaced other cadres in her village. She noticed that cadres came to replace other cadres, but did not know where they came from. Ordinary villagers, however, were not allowed to meet them. Since she did not meet them, she never heard them speak and did not know whether they had a different accent to those who they replaced.

The disappearance continued after the arrival of the new cadres. With this, Mr. Koumjian concluded his line of questioning and gave the floor to the lawyers for the Civil Parties.

Distinguishing ethnic Khmer from ethnic Vietnamese

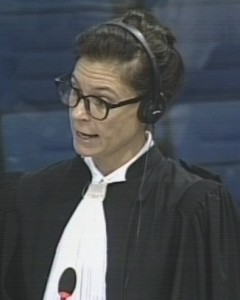

International Lead Co-Lawyer for Civil Parties Marie Guiraud

International Lead Co-Lawyer for Civil Parties Marie Guiraud turned to the topic of mixed-blood children and children of mixed-blood parents. She asked whether it was possible to distinguish mixed-blood children from other Khmer children by their physical features. She replied that she knew from the people in her village whether they were of mixed ethnicity or not.

Ms. Sak explained that mixed children looked similar, since they had dark complexion. She knew that they had a Vietnamese and a Khmer parent. She clarified that Van Mao, for example, looked like his father and therefore had dark complexion, while Ms. Sak herself more looked like her mother and therefore had lighter skin. Asked how they therefore could distinguish Vietnamese from ethnic Khmer, she replied that she knew it in her village, but thought that in other villages chiefs might have made reports. Ms. Guiraud asked whether these reports were something she had heard of.

Witness Sao Sak

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe interjected and stated that the witness should be instructed to say only those things that she knows instead of those things that she “may know”. Ms. Guiraud answered that this was exactly what she wanted to find out with her questions. Ms. Sak replied that “when they did the reports”, this concerned the ethnic Khmer and she did not know about the Vietnamese.

Ms. Sak’s mother did not speak Vietnamese, but understood when Vietnamese people spoke to her. “All half-blooded children did not speak Vietnamese”, since they were not born in Vietnam.

Ms. Guiraud read out an excerpt from Ms. Sak’s statement on Thursday in which she had said that ethnic Vietnamese were “assembled and evacuated to the lower region.”[4] Ms. Sak confirmed having said this. “They assembled people and were sent somewhere. Each family was collected and sent away and they disappeared.” Some disappeared at night time and some during day time. “This is what I heard from people.” She did not know who came to assemble people. “I only knew that people disappeared.” There were no language tests. She heard from other people that those people were sent to Vietnam.

Turning to her last question, Ms. Guiraud asked whether she heard from a cadre or a militiaman that these people were evacuated from Vietnam, which Ms. Sak did not confirm. Other “fellow villagers” had told her about the matter.

Massacres of Vietnamese prior to 1975

The floor was then given to the Defense Counsel for Nuon Chea. Victor Koppe started his line of questioning by inquiring whether it was correct that she was 17 years old in 1970, since she was born in 1953. She did not leave her village, but only lived in Anlong Trea. She did not have family outside her village. She did not know about other ethnic Vietnamese outside of her village. Mr. Koppe then wanted to know whether her mother had ever told her about mass executions of Vietnamese in 1970, mass evacuations or campaigns against Vietnamese in 1970, which the witness denied.

Mr. Koppe referred to her testimony in Court last week, in which she had said that they had a “normal relationship” before 1975, whereas the Vietnamese people were “later sorted.”[5] Mr. Koppe asked whether she specifically “limited” her answer to those people of Vietnamese origin. She replied that ethnic Vietnamese and ethnic Khmer had “no trouble in their relationship.” When the Vietnamese were “taken out”, the ethnic Khmer people also did not know “what was happening”.

Mr. Koppe inquired whether she had never heard about mass executions of Vietnamese during the Lon Nol regime. She said that she had never heard about this, since this did not concern ordinary villagers.

He asked whether she had heard of the execution of 800 Vietnamese, whose bodies were thrown into the Bassac River. She said that she had never heard about this. She did not know about many Vietnamese people being accused of treason during the regime, “because my family was poor, we did not have a radio.” Neither had she heard of mass executions in Takeo before 1975.

At this point, Marie Guiraud interjected and asked for the references.

Mr. Koppe replied that he wanted to put one last question before giving reference: He inquired whether Ms. Sak had heard of anti-Chinese campaigns, during which ethnic Chinese people were being threatened with executions. She denied knowledge of this. Mr. Koppe then gave the reference, which was a book by Elizabeth Becker.[6]

Turning to the next topic, Mr. Koppe inquired whether she had ever heard about a magazine or paper called Revolutionary Flag, which she denied. “I lived in the countryside and I never saw it.” She had not listened to Radio Phnom Penh. “Of course not. During the regime, people were not allowed” to receive news. Neither did she know anyone who listened to the radio. “We did not think of politics”, since they were struggling to survive.

Authority Structures and policy

Mr. Koppe then asked whether the cadres in her village were the only representatives of Democratic Kampuchea that she spoke with or had contact to, which she confirmed. “I only interacted with the cadres in my village.” Mr. Koppe then asked whether it was fair to say that she did not know what the policy towards the Vietnamese was at the time, which she confirmed.

In her Written Record of Interview she had referred to “events of Sao Phim”.[7]. Mr. Koppe inquired what she had meant with this. She replied that after the events of Sao Phim – which is how it was called – soldiers who returned to their villagers were called to return. She did not know who Sao Phim was but only heard about his name. She answered that people talked about the “confusing situation” at the time. The villagers did not say anything else. Her village was situated in Sector 24, but she could not remember the Zone. She had heard of the name Heng Samrin, but did not know his face. She did not know anything else. Mr. Koppe inquired whether she knew that there was any fighting between the Democratic Kampuchea government and Vietnamese troops. “Did you ever hear the sounds of war?” She said that she did not.

Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that she never witnessed anyone being killed, which she confirmed. With this, Mr. Koppe finished his line of questioning.

The President Nil Nonn adjourned the hearing for a short break.

Detention of the witness

After the break, the floor was given to Khieu Samphan Defense Team. International Co-Counsel Anta Guissé inquired about Ms. Sak’s arrest. She had stated that she was detained for around ten days and had made mention of an older woman named Che.[8] Ms. Sak remembered that Yeay Cha was “simply an ordinary citizen”

In her statement, she had mentioned the ethnic background of that person.[9] Ms. Sak recounted that the person had said to be Cham. She did not know whether the person was Cham, but she knew that her father was Cham. She confirmed that this person was released.

International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

Ms. Guissé then turned to the authority structure of her village. She asked what the role of the cadres from her village Man, Kok, Chhoey and Ny was. Ms. Sak replied that Man was the village chief in Anlong Trea. Man “invited [her] to go to the pagoda.” She confirmed that she only spoke to Man. She did not know the immediate supervisor of Man. Chhoey was commune chief of Preak Chhrey. According to Ms. Sak, Kok was the village chief together with Man. Ny was the chief of militia.

Ms. Guissé asked whether it was correct that she never attended any meeting with Man, Kok,Che and Ni, which Ms. Sak confirmed. However, she was in meetings during which they discussed rice production.

At this point, Mr. Kong Sam Onn took the floor. He asked who told her that people were arrested and sent back home. She said that it were not the village chiefs. “It was our thought that the Vietnamese were arrested and sent back to Vietnam.” When Mr. Sam Onn pressed on and asked who told her so, she said that there was a rumor and that they whispered this to each other during lunch time. Asked by Mr. Sam Onn, Ms. Sak clarified that Ni was the militia chief of her village.

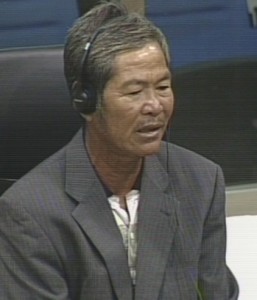

Civil Party: Choeung Yaing Chaet

The President thanked the witness and dismissed her. He then invited Civil Party 2-TCCP-241 into the courtroom.

Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet is 52 years old and was born in Ruessei Dangkuoch Village, Prey Kry Commune, Kampong Leang district, Kampong Chhnang Province. He now lives in Kandal Village in Kampong Chhnang Province. He is father of eleven children.

Forced transfer

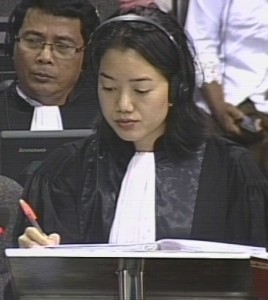

Civil Party Lawyer Lyma Nguyen

Civil Party Co-Lawyer Lyma Nguyen asked whether the Civil Party was of Vietnamese ethnicity, which he confirmed. He also confirmed that both of his parents were ethnically Vietnamese. His parents were also born in the same village. He spoke both Khmer and Vietnamese in his village. He spoke Vietnamese with his parents, who also spoke Khmer. Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet recounted that they lived in a village adjacent to a Khmer village, so they also spoke Khmer. Her parents could “speak 60% of Khmer.” They celebrated Vietnamese New Year and other holidays. The calendar of the Chinese was a month different to the French calendar. The Vietnamese and the Chinese calendar were the same. He had male and female siblings. He confirmed that he had two older sisters and two older brothers in 1975.

He did not recall the date of his siblings’ births. His older brother’s name was Choeung Yan Khuoy, his younger brother’s name was Choeung Yang Leuy; the names of her sisters were Choeung Yan Dy and Choeung Thi Lit. His sisters were Vietnamese. When she asked whether his siblings had Vietnamese citizenship, he replied that his older brothers received the letter.

After he had mentioned that his family had been mistreated in Ruessei Dangkuoch village, Ms. Nguyen wanted to know how this took place. He answered that they were severely mistreated and had to flee to Kampong Chhnang. They had been told that if they remained in the village, they would all be killed. There were more Khmer families living in Ruessey Dangkuoch village. Around 30 or 40 families lived there. There were Khmer, Vietnamese and Cham families coming to live in the village.

Asked for clarification, the Civil Party remembered Ta Peang’s group told him that they would all be killed. He confirmed that it was also District 18. In 1975, he moved to Kandal Village in Kampong Chhnang, before being evacuated in Dar after a month. In this month, he caught fish. They were forced to relocate. They were taken to Dar and divided into groups there. Some had to go fishing while others had to work on land. There were around a thousand families who were relocated to Dar Village. He could not recall the ethnic composition of the relocated families. He then said that “it [is] likely that there were more Vietnamese families.” Kandal Village was around 15-20 kilometers away from Dar Village. His group was composed of only Vietnamese families, while other groups were composed of both Khmer and Vietnamese families.

He did not recall the name of the Dar Village. Ta Peang “was the chief of the Pol Pot group”. Dar was also located in District 18. It was located on Kangkeb Mountain. They were given gruel mixed with morning glory three times a day. He was asked to clear the land to grow potato. His family lived there for around a month before they were killed.

Asked whether they expected his family to be killed, he answered: “They never thought about that. If we knew that we were to be killed, we would run into the forest, either to be eaten by a tiger. But we did not know anything about that.”

Killing of his family

His parents were clearing the land, while his father and he himself had a fever. The next morning, eight men came with eight guns and an ax. They asked their father to come out of the house first. His mother became unconscious while his father was tied up. “Then, each of the family members was tied up by a rope that was used on cows.” Next, they walked them away. His whole family was there. This happened at 8 o’clock in the morning. His whole family was there.

As for the eight men, he recounted that they were Ta Peam’s group. They wore black uniforms and a scarf around their neck. They had eight guns and an ax and grenades. Regarding his father, “They took him near the pit where they would execute him.” This was around 100 meters away. “However, I did not see them kill my parents. When I arrived at the pit, I saw their dead bodies in the pit – that is the bodies of my father, my mother and my siblings.”

They tied their hands behind their backs. All his sisters and brothers were tied up. “Then we were lined up in a queue and then they walked us into the forest.” They were tied up individually, but were walked in a line “in order to prevent any of us from escaping.” He did not know what happened to other families. “I had been hit three times by an ax on […] my neck”, and since then his memory is not very good anymore, he said.

When Ms. Nguyen asked about the Khmer Rouge’s acts, Mr. Koppe objected and reasoned that the Khmer Rouge was a too broad term and referred to an entity that could not commit acts as such. Ms. Nguyen rephrased her question and asked whether Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet had seen the cadres treating other villagers in a similar way. He recounted that another family was also tied up at the same time as them. They walked them from the house to the forest, the distance being around one kilometer. They stopped around 100 meters away from the pit. “Each of us would be taken one by one to be killed at the pit.” Four cadres guarded the group, while four cadres individually led them to the pit. The pit was three meters wide and 1.5 meters deep.

Civil Party Choeung Yaing Chaet

When reaching the pit, “each of us would be taken and killed. They would kill, untie and push the person into the pit. And when it was my turn, I was ordered to kneel down and then they felt my neck and they use an ax to hit […] my neck three times.” He was the last person in his family. “And by that time, all of the eight cadres were there. ”

And they presumed I was dead, then they untied me, took the rope and left.

He only saw four of his family members, “because they were stacked on top of another. I saw the body of my father, my mother and my siblings.” He did not see the bodies of the other family. “It is possible that they were stacked up below the body of my parents. And by the time I was there kneeling at the pit, I was dizzy”, he recounted.

He further told the Court:

I was ordered to kneel down. After I knelt down, they pulled my legs. By that time, I lost my balance and my head moved a bit forward. Then they felt the net of my neck. They hit it three times. They dropped me off into the pit; then they untied me.

He regained consciousness around 4 pm. “I could not walk. I had a very severe pain at my neck. It was swollen.” After walking dayand night to Kroue village, he entered the house of Ta Ly.

Ms. Nguyen wanted to know what he was thinking and feeling at the time that he was in the mass grave, since he was only 13 or 14 years old at the time. “Frankly speaking, I did not think of anything. I was just reborn. So I walked that night and I reached the floating Vietnamese village. I saw Ta Ly. Then they helped me. They gave me some modern medicine and also traditional medicine in order to treat me.”

Ta Ly was ordered to catch fish. “When I reached that location, I told them that all of my family members had been killed and that I was hit”, but that he survived.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Confusion about the date

After the lunch break, the Chamber issued a partial oral ruling on the Request to call for additional witnesses.[10] On December 1, the oral responses were made. The Civil Party lawyers supported the request, while the Khieu Samphan Defense Team submitted that the submission was tardy and

The President stated that the Chamber was satisfied that the relevant evidence was not available at the beginning of the trial, and therefore granted the request. They assigned the pseudonym 2-TCW-1000, and also admitted the relevant Written Records of Interviews.[11]

Mr. Koppe requested clarification regarding the dates, since the first page if the Civil Party interview indicated that in Western calendar, the events took place on 17 March 1975, which would be outside the scope of this trial.[12] There was some discussion regarding the confusion of the difference in Western and Vietnamese calendar, since the Civil Party Supplementary Information Sheet indicated on one page that the Western calendar was behind and on another that it was ahead of the Vietnamese calendar. The witness clarified that the events took place seven days after Khmer New Year and that his family was killed one month after Khmer New Year. When talking, he was referring to the Vietnamese calendar.

Escape to Vietnam

Ms. Nguyen proceeded and asked how long he stayed at Ta Ly’s house after the “horrific mass killings of your entire family.” He stayed there for one month before there was someone who told them that the Vietnamese had to leave to Vietnam by boat. Ta Ly told him to stay in the house. He stayed there for two weeks and after a month, Ta Ly left for Vietnam. Ta Ly told him that eight family members could go to Vietnam by boat. “I was able to go on boat” at the time. Ms. Nguyen then inquired whether this was subject to policy, which Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet did not know. “At the time, I was able to hide in [Ta Ly’s] boat.” When they reached the intersection of the river “I was able to board a motorboat.” Ms. Nguyen then asked why he had to hide. He replied that there were only eight members in his family and that he had to hide. When they reached the intersection, he could get out and help paddling the boat.

They were travelling to another location. After reaching Tonlé Bouan Moek, they could board the motorboat and left for Neak Loeung. “And I don’t know about the exchange of rice with Vietnam.”

Ms. Nguyen Place then inquired whether Tonlé Boean Mouk was the place in front of Royal Palace in Phnom Penh, which the Civil Party confirmed.

They travelled three nights before reaching the tributary. When they reached it, he went onto a ferry with other people. Ms. Nguyen inquired whether the people were Vietnamese or also Khmer. He replied that “there were all Vietnamese on the ferry.” Khmer people would not be allowed to cross. He did not know whether the ferry belonged to the Khmer Rouge or to the Vietnamese. However, Khmer Rouge instructed them to board the ferry.

When Ms. Nguyen asked how the Khmer Rouge identified them, Mr. Koppe interjected. He argued that Khmer Rouge was a too generic term and Democratic Kampuchea had not existent until 1976. In his view, National Front would be correct when referring to the year 1975.

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

Ms. Nguyen replied that the Civil Party himself had identified the people as Khmer Rouge. The objection was overruled. The President explained that the term Khmer Rouge has been commonly used – in line with public opinion. Thus, the ECCC was commonly known as Khmer Rouge Tribunal.

Ms. Nguyen then asked how the Khmer Rouge identified those people who were allowed to go onto the boat. At this point, Mr. Kong Sam Onn objected and stated that it was a repetitive question. The objection was overruled.

The Civil Party replied that they asked who was Vietnamese, Chinese or Khmer. Since Vietnamese spoke Khmer with accents, they could easily be identified. The Khmer people “faced the same difficulties as I did.” When they arrived to the ferry, they were not allowed to board the ferry. He did not know anyone on the boat. “I just mingled with the rest.” He could not recall who were supervisors on the ferry “because they were all wearing black uniforms with a scarf around their neck.” However, they did not wear any weapons. He confirmed that they travelled to Neak Loeung in Prey Veng. It took them one night and one day to arrive. They left in the early morning.

In Neak Loeung they were supposed to negotiate with the Vietnamese side. There was a headcount of the Vietnamese people. In exchange, the Vietnamese gave salt and rice. After this negotiation, they were allowed to board a Vietnamese ferry. “I saw only rice and salt and nothing else.” There were no Vietnamese authorities on the boat. The Vietnamese together with the Cambodian authorities counted heads.

Ms. Nguyen asked whether he personally saw the trading of rice and salt for Vietnamese persons, which he confirmed. “In fact, you were one of the ones who were traded for rice and salt.”

At this point, Mr. Koppe objected to the word “trade”, since this trade had not been established.

Ms. Nguyen replied that the Civil Party had used the words “bartering process” at least three times in the Civil Party Application; Vietnamese lives had been spared for rice and salt and it was insignificant whether this was called swapping or exchange. Mr. Koppe argued that “He might have perceived it as a bartender or a trade, but of course it wasn’t.” Mr. Kong Sam Onn supported Mr. Koppe’s argument and stated that this seems to have taken place immediately after 17 April Victory, when no proper administration existed. The acts could not be defined as bartering process.

international Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

President instructed the Civil Party lawyer to ask the Civil Party for the basis of his characterization as bartering. Ms. Nguyen asked what him consider that this process was a transaction and a trading process. He replied that he heard other Vietnamese people say that his life was spared for the exchange of rice and salt so that he could go to Vietnam. He was unable to tell how many bags of rice and salt there were. After having done the headcount, they exchanged the number of people for the number of bags and salt. Asked to clarify this, he said that he did not know whether the number of people equaled the number of bags and salt, but that he saw them doing the headcount and then carrying the bags. The ferry then headed off to Vietnam.

When they arrived in Vietnam, “the Vietnamese Angkar allowed us to rest” and gave them food, cooking utensils, sleeping mats and mosquito nets. He stayed in Vietnam until 1982, when he returned to Cambodia. He returned, because he “had no land to farm”. He came with other people and “helped them row the boat.” When he left Cambodia “I had nothing, because everything was burned.”

As for the memory loss that he suffered due to the strokes on his neck, he explained that “whenever I feel anxious, I cannot recall anything.” Ms. Nguyen then asked whether he had ever forgotten what had happened to him. “I witnessed the executions of my parents and my siblings. It happened right in front of my eyes.” He considered himself lucky that he survived the three strokes on his neck, although it sometimes still hurt depending on weather “I cannot forget what happened to me. I really want to ask the perpetrators how they were suffering if they had their family members killed.” With this, Ms. Nguyen finished her line of questioning.

International Assistant Prosecutor Andrew Boyle

Assistant Prosecutor Andrew Boyle asked when the Khmer Rouge took power in his home village Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet replied that it took place in the fifth month of Vietnamese calendar 1975 when he noticed their powers. He confirmed that the majority of his village was Vietnamese. They were instructed to leave their houses under the threat of burning down their houses even with people inside. He recounted that there were also Cham families in Dar Village. As for his home village, the Khmer people remained in their village. “If no one lived in houses, those houses would be burned down.” Mr. Boyle asked whether the members of the commune knew who was ethnically Vietnamese and ethnically Khmer in his village. The answer remained unclear.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Distinguishing ethnic Khmers from ethnic Vietnamese

After the break, Mr. Boyle took up his line of questioning again and repeated his question from before the break. He explained that they knew who was Khmer and Vietnamese through family record books. The Khmer Rouge knew who was Khmer and who was Vietnamese. Mr. Boyle asked whether the Khmer Rouge asked to look at the langdtay, which the Civil Party confirmed.

At this point, Mr. Koppe objected again, stating that the Prosecution should refrain from using the word Khmer Rouge. “It is maybe one thing if the Civil Party lawyer does it, but the Khmer Rouge as such” could not commit acts. Mr. Boyle responded by saying that this objection had continuously been made and been overruled. He asked to be able to proceed. The objection was overruled. Mr. Boyle repeated his question and asked whether the Khmer Rouge used lists to identify who had to leave the village. The Civil Party replied that there were around 30 families coming from Ruessei Dangkuoch. He further remembered: “The langdtay were looked at”. Those who wanted to live on the mountains were allowed to do so, as were those who wanted to live on floating villages.

Mr. Koppe stated that the line of questioning implied that the families were arrested because they were Vietnamese, whereas they might have been arrested and happen to be Vietnamese. Mr. Boyle replied that his questions were neutral, whereas the Nuon Chea imposed this interpretation on themselves. The objection was overruled.

Mr. Boyle asked whether the Civil Party was aware of any other families who were arrested on the mountain. Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet replied that he did not know. “I knew I was going to die, since my family had been killed.”

Judge Claudia Fenz

He saw two pits. One was “fully of [his] family members”, while the other one was empty.

Mr. Boyle then inquired whether the Civil Party saw many other boats travelling alongside their boat, and if yes, how many. He replied that “some people had been already on the ferry.” He noticed around 50 or 60 other boats along his boat. “We were rowing boats in groups.” All of these people were Vietnamese. “There was no other ethnicity.” He saw only one ferry. “There were around 50 or 60 people on that ferry and I was told by Ta Ly to board the ferry without saying any word, because otherwise Ta Ly would be killed.” They left around 8 am and arrived in Neak Loeung at around 4 am.

Judge Claudia Fenz briefly asked a few questions. She wanted to know who kept the family record book: was it the village chief or somebody else? The Civil Party replied that it was the family itself. He could not recall who issued the family record book. Judge Fenz then asked whether he knew if there was a central register in addition to the record book that was handed to the families. Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet replied that he did not know.

Back to the issue of the calendar

The floor was granted to Defense Counsel for Nuon Chea. Mr. Koppe asked whether the Civil Party was able to read or write English, which the Civil Party denied. “I did not go to school.” He explained that he was so poor that he could not go to school to learn Khmer or Vietnamese, so he was uneducated at the time. Mr. Koppe clarified that he meant whether Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet was able to read and understand English in 2010, which the Civil Party denied. This prompted Mr. Koppe to request leave to present the Supplementary Statement to the Civil Party, which was granted.

Mr. Koppe inquired whether the Civil Party recalled having put his thumb print on the English version in 2010.[13] Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet replied that he knew the Vietnamese language, but did not know Khmer and French. He could recall putting his thumb print on the document. Mr. Koppe inquired whether the content of the document was read out to him either in Vietnamese or in Khmer. He replied that it was read to him in Khmer. Mr. Koppe asked whether Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet agreed to the content and that he put the thumb print, because he agreed. The Civil Party confirmed this.

Mr. Koppe explained that on the document it was mentioned twice on the first page that the events took place on the 17 April 1975 according to Vietnamese calendar, which equaled 17 March 1975. Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet replied that the evacuation took place seven days after Khmer New Year. One month later, his parents and his family had been killed.

Mr. Koppe then asked whether it was Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet’s testimony that the document was incorrect in stating that this event took place on 17 March 1975. The Civil Party replied that he could not remember the specific date. “If you talk about months, I could recall, but if you talk about specific dates, I could not recall.” Mr. Koppe repeated his question and asked whether it was correct or false that his family was killed on the 17 March of 1975. He recounted that he told them about the month and the year when he was asked about the time that his family members were killed. Mr. Koppe asked whether the Civil Party was now saying that he did not know when the alleged killings took place.

Mr. Boyle objected and stated that the Civil Party had been consistent and clear for the date in regards to Khmer New Year. Mr. Koppe stated that the testimony today still said that it took place in March 1975 and that this could still be used as evidence. To this, Ms. Guiraud stated that the question had already been answered and that this was repetitive.

After a brief deliberation, the President handed the floor to Judge Fenz, who instructed Mr. Koppe to move on. The Chamber would have to make a decision about which date to rely on.

Role of Ta Peang

Mr. Koppe asked who Ta Peang was. Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet replied that he was the supervisor of Kampong Leang District and that this was said by everyone. Mr. Koppe then asked how long Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet saw Mr. Ta Peang. The Civil Party replied that he evacuated him.

Mr. Koppe asked whether what Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet was saying that he was involved in the evacuation, the killing of his family, and putting Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet to put on a boat. Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet stated that he did not remember what happened next after he was in pain and lost his parents. The Civil Party confirmed that Ta Peang was involved in the transfer of his family to Dar. Ta Peang instructed him to build accommodation. Once having arrived in Dar and giving instructions, Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet did not see him again. He did not know whether Ta Peang was involved in the killing of his family or not. He did not know where Ta Peang went after the accommodation was finished. His father was responsible for leveling the land, and when he was sick, he was taken away and killed. Mr. Koppe asked how long Ta Peang knew the Civil Party’s family before the evacuation to Dar. Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet replied that he did not know whether Ta Peang knew his family beforehand.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing, which will continue tomorrow, December 08 2015, at 9 am. Reserve witness will be 2-TCW-945.

[1] E3/2589, at 00224670 (KH), 00623348 (FR), 00224673 (EN). [2] E3/5235, at 00824184 (EN), 004551643 (KH), 00869284 (FR). [3] At 00238898 (KH), 00281807 (FR), 0024216 (EN). [4] Testimony of Sao Sak, December 03 2015, at 15:20. [5] Testimony of Sao Sak, December 03 2015, at 14:33. [6] E3/20, at 00237829-30, and 00232165-66. [7]E3/7783, at 00235511 (EN), 00233296 (KH), 00250600 (FR) [8] E3/7780. [9] E3/7780, at 00250601 (FR), 00235512 (FR) 00233296 (KH). [10] E319/36 [11] E319/23.3.44, E319/23.3.45, E319/23.3.46, E319/23.3.47, and E319/23.3.48. [12] E3/5631 [13] E3/5631, Supplementary Statement, 21 December 2010.

Featured Image: ECCC: Flickr.