Witness Testifies on Treatment of Vietnamese and High-Ranking Lon Nol Officials

In the morning of today’s session, December 8 2015, Choeung Yaing Chaet’s testimony came to an end. He gave further details relating to the killing of his family and his journey to Vietnam. Next, former battalion chief Prum Sarun was questioned by the Co-Prosecutors and Civil Parties. He recounted how several Vietnamese people were arrested in the neighboring battalion. The questioning of the Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde then focused on the targeting of Lon Nol soldiers.

Clarifiations

At the beginning of the session, the Trial Chamber Greffier confirmed the presence of all parties. Next, the testimony of Civil Party Choeung Yaing Chaet began. Witness 2-TCW-945 was on the reserve. The floor was handed to the Defense Counsel for Nuon Chea, who took up his line of questioning by returning to the discussion about the time when the events took place. In one of the documents, he

In the document by the Victim Support Section, two killings had been described: the one of his family at the beginning of 1975 and one half a year later.[1] Moreover, it had been indicated that his region was located in District 18. Mr. Koppe inquired whether it was correct that the area that he lived in was already liberated by the “Khmer Rouge”[2] in 1975. Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud remarked that the report from the VSS was exactly that – a report. No contact had taken place at this stage between the Civil Party and VSS.

Mr. Koppe repeated the question. The Civil Party replied that Kampong Leang was in District 16 and that some people from District 18. He did not know who the Secretary was of District 18. He had never heard of someone called Ouk. He also had not heard of someone called Boun Than. Mr. Koppe then asked whether Ta Peang himself was Vietnamese, which the Civil Party was unable to tell. “I did not even dare look at his face”.

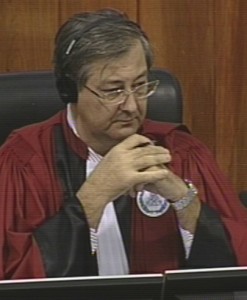

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne interrupted the examination of the Civil Party and asked what the basis was for asserting that Ta Peang was Vietnamese. Mr. Koppe replied that it was on the CaseFile. After Judge Lavergne pressed on, Mr. Koppe gave the reference.[3]

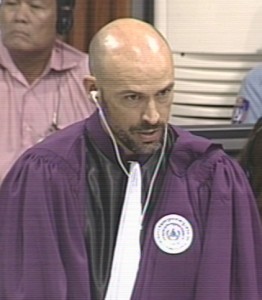

Assistant Prosecutor Joseph Andrew Boyle

Assistant Prosecutor Andrew Boyle interjected and stated that this was an S-21 Confession Document. This was obtained under torture. The Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn ruled that Mr. Koppe could not rely on a document that was obtained under torture. Mr. Koppe explained that his focus of the questions was on when the area was liberated. He based himself on Kiernan, who had indicated that parts of the West Zone were already liberated in 1971. Mr. Boyle clarified that it was actually correct that Kampong Leang was in District 16. Mr. Koppe replied that the Civil Party had repeatedly said that it was in District 18 and that this was also confirmed in the document he was not allowed to use.

The Civil Party replied that he was not yet in Kampong Chhnang in 1971. He had moved there one month before Khmer New Year and was relocated seven days after Khmer New Year. This took place after 1975.

Mr. Koppe moved on and asked whether there was anyone in his surrounding that he described the story to. “Is there anyone who could corroborate your evidence?” Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet replied that Ta Ly passed away already, and he did not know anyone else.

Mr. Koppe then turned to the topic of memory loss. The Civil Party had stated that he forgot 30% of things as a result of the injury he suffered.[4] Mr. Koppe wanted to know what made him say that he forgot this particular percentage. The Civil Party replied that this was simply a fact. Asked about mental issues that he had said that arise when he works hard due to the injury. “Is there something not going well in your head?” The Civil Party stressed that this was a consequence of the injury he had suffered.

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

Mr. Koppe then turned to the report in which he had mentioned the killing of 40 villagers. In this document, it seemed like he was hit on the neck in this group and not while being with his family. The Civil Party replied that he saw the 40 villagers being killed while hiding in the forest. He was already injured on his neck when he saw them. He had been instructed by Ta Ly to hide in the forest.

He did not know what happened to the other families from his birth village. Some were sent to Dar Village. In his Supplementary Submission, he had mentioned 2,000 people who were relocated.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know what made Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet think that he was bartered for rice and salt. The Civil Party replied that “that’s what Angkar on the

ferry said about that. They said that I was bartered for rice and salt.” This was on the Vietnamese ferry by Vietnamese authorities. He confirmed that he was never told this by Khmer authorities in Cambodia. “So do you agree with me that there is zero evidence that your family was killed, because they were Vietnamese?” Mr. Boyle objected to the form of the question, but the President interrupted his argument. The President then instructed the Civil Party not to answer the question.

When Mr. Koppe rephrased the question, the President prevented the Civil Party from answering this leading question. Mr. Koppe thanked the President and finished his cross-examination.

Relocations

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé turned to the transfer of families from Kandal Village to Dar Village. He had indicated that 1,000 families were relocated that were both Khmer and Vietnamese. She wanted to know how he had “come up” with the number of 1,000 families. He replied that this came from his estimation. There were around 40 or 50 groups with “many people” in each group. The gathering took place near the river. They were sent to Kaep Mountain/Dar Mountain. Ta Peang had instructed to build a shelter and was responsible for the displacement. The Civil Party’s parents had told Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet so. During the evacuation, they were told that those “who were on the ground” had to walk, while “those who were on the water” had to remain on the water. The instructions came by the Khmer Rouge with their black uniforms and red scarves.

Ms. Guissé referred to his Supplementary Information sheet in which he had said that around 2,000 people were displaced.[5] He said that it was just an estimate. “I said only what I knew.”

Internationla Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

Turning to the burning of houses, Ms. Guissé asked whether the burning of houses happened when he was leaving the village, which the Civil Party confirmed. He confirmed that his family record book had been with his family. All his belongings were burned. He could not remember when his family record book was checked. It was at Kampong Chhnang at Dar Mountain. During the Khmer Rouge, they only made statistics about how many people were in the family and who was the head of the family. The family record book was made during the Lon Nol regime. The Khmer Rouge asked about the number of family members and names.

Ms. Guissé then asked him to recount the killing of his family. He repeated the story. Ms. Guissé asked about the execution of his mother in the house. There had been confusion about the translation, since his mother became unconscious in the house and was not executed. He had not seen the people who arrested them before. According to him, base people wore black clothing with a scarf around their neck. Militiamen wore ordinary clothes. “It was the clothing that we wear at the present time.”

The location where they were brought to was around a kilometer away from his house.

Journey to Vietnam

After the break, Ms. Guissé asked to confirm that it took him one day and one night to reach Ta Ly’s house, which he did. Ms. Guissé asked whether he remembered having to fill out a form to become a Civil Party.[6] In this form, there was no mention of stay at Ta Ly’s house.[7] The Civil Party reaffirmed that he stayed at Ta Ly’s house.

In his supplementary statement, he had indicated that it took him one hour to reach Ta Ly’s home and not one and a half days, as indicated in his testimony.[8] He reiterated that it took him one day and one night. He did not know why it was stated in this document that it took him one hour.

In one document, it was indicated that he stayed in the commune of Samraong Sen.[9] He answered that he had stayed at Ta Ly’s house for 2.5 months. Afterwards, he was able to reach Samraong Sen. He went to Samraong Seng on the way to the boat to Vietnam. Ms. Guissé stated that she had understood his testimony yesterday that he took a boat from Ta Ly’s family, from where he was directly transferred to the ferry. He replied that he went to Samraong Seng first and then took a boat. Asked for clarification, he recounted that after seven days of staying in Samraong Seng, Ta Ly called him back to be on another boat before taking the ferry. Ms. Guissé asked what he meant with a letter that he had mentioned before. He clarified that a letter had been issued for Ta Ly’s family, stating that his eight family members could go to Vietnam. Ms. Guissé asked whether Ta Ly had made a request so that the family could go to Vietnam, which he did not know. “I was able to hide in his boat.”

When he arrived at Neak Loeung, the “Khmer Angkar” discussed with the “Vietnamese Angkar”. He did not know the specifics of the bartering process. Ms. Guissé then asked whether he would be able to make any corrections if there were any inaccuracies in E3/5631. He said that he did not wish to make any corrections.

National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn

Her national colleague Kong Sam Onn took over and asked whether the Civil Party had ever heard about the aerial bombing in 1975 when he was in Kampong Leang District. He recalled that there were rockets in the sky, so he was “hiding in the trenches”. This happened “from time to time”. He did not know what happened in other villages. There were two aerial bombings in his village. He sometimes heard the sound of the bombing. He did not know about any military matters.

Mr. Sam Onn referred to Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet’ supplementary information and inquired which statement was correct.[10] The Civil Party replied that the statement that he went to Dar Village from his birth village was correct.

He did not know what the langtay document looked like, since he had never seen it. His parents only told him that they hid it in the house. Mr. Sam Onn inquired whether Vietnamese people were allowed to board the ferry at the tributary, which the Civil Party confirmed. Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet stated that the boat approached the ferry, which they could board. There were many boats next to the ferry, but he did not know who they belonged to. This took place “right at the island” at the tributary. He confirmed that the ferry parked next to an island and not opposite the Royal Palace. There were around 50 or 60 people on the ferry. He could not remember the width or depth of the ferry, but estimated its size. There was a roof at the backside of the ferry, but the front was uncovered. He could not remember whether there was any flag or not – “I was fleeing […] of course I did not pay any attention.”

He did not see any exchange of documents. There could be around 25 or 30 boats that arrived after he had arrived. After his arrival in Vietnam, they rested at a school. “I was at that school for seven days. Then they signed a letter or something.”

Mr. Sam Onn then asked: “Was it a concentration camp?” Mr. Choeung Yaing Chaet replied that they did stay in a camp and did not mix with Vietnamese people. He tended water buffalos for a year and stayed at the owners’ place, where he received rice and some clothes. The Vietnamese-Cambodians were sent to different parts of Vietnam. His group was the first one to arrive. With this, the cross-examination came to an end.

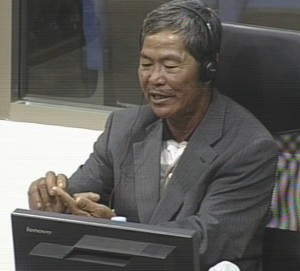

Civil Party Choeung Yaing Chaet

The President then gave the Civil Party to the floor to give a Victim Impact Statement about the suffering and harms that he underwent. Instead of a Victim Impact Statement, the Civil Party posed a question to the two accused:

I’d like to put questions to them. For example that I suffered from the loss of my parents, my family members and that I am by myself with my head injury. And for them, if they were in my position, how would they feel? That is the question, Mr. President.

The President informed the Civil Party that the two accused exercised their right to remain silent and maintained their position. National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang stood up and stated that the Civil Party did not understand his entitlement to make an impact statement. He said that Lyma Nguyen sought permission to explain the impact statement again. The President denied the request and thanked the Civil Party. He then instructed the court officer to usher the next witness in.

New Witness: Prum Sarun

Witness Prum Sarun was born in 1942[11] in Krapeu Cheung Village, Phnom Sampeou Subdistrict, Banan District, Battambang Province, where he also currently resides.

After the lunch break, the floor was given to the Co-Prosecutors. National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Song Chorvoin took her stand and inquired about his life before 1975. Before April 1975, he lived there as well. He was chief of a platoon. His district was located in Sector 3 in the Northwest Zone. His platoon was under Company Number 1 in Krapeu Cheung Village. Ta Hong was his immediate supervisor. Ta Hong was chief of a company in their village.

Authority Structure

He was interviewed by the investigators of the OCIJ, and had said that he had been chairman of battalion number 4 under Company Number 1.[12] He replied that he was under Battalion Number 1 and Company Number 4. The battalion did not belong to any sector but to the district. Ta Kroch was the chairman of Battalion 1.

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne

Ms. Chorvoin then moved to the treatment of the Vietnamese. She wanted to know what happened to the Vietnamese in his battalion and other battalions. “There were Vietnamese and they were killed Tuol Ta Trong.” He further recounted: “The Vietnamese were called to a meeting and killed near Tuol Ta Trong.” There were no Vietnamese within his battalion. However, there were Vietnamese within other battalions, who were “killed and smashed.” Ta Kroch never searched for Vietnamese in his unit, since there were no Vietnamese within his unit. There were many Vietnamese in Battalion Number 2. There were Chinese in his battalion.

In his statement, he had indicated that Krouch asked him to identify Vietnamese in his battalion, if there were any, so that Kroch could inform the Center.[13] Mr. Sarun recounted that Kroch asked him about the Vietnamese at the place where they grounded the rice. However, there were only Chinese in his group. Mr. Chorvoin then asked whether Krouch told him who the upper echelon was. He replied that the upper echelon was the regiment leader. Ta Cham was the chief of the district. Ms. Chorvoin asked what Ta Krouch had meant when saying that the Vietnamese had to be sent to the upper echelon to “handle” the Vietnamese. Mr. Sarun explained that to handle meant to kill. Ta Krouch did not ask anything specific, except whether there were Vietnamese in his unit.

Arrests of Vietnamese

Battalion Number 1 and 2 were stationed next to each other. They made up the battalions for his birth village. Mr. Chorvoin then asked whether Mr. Sarun ever witnessed the arrests of Vietnamese within the Commune or Sector. He replied that the Yuon were arrested within Battalion Number 2 and “sent to the upper echelon”. He did not know where exactly they were sent to, he only noticed their arrests. Two Vietnamese in Battalion Number 2 had been arrested and sent away.

He had said in his statement that around 20 Yuon, who were in Battalion Number 2, were arrested. Ms. Chorvoin asked to clarify how many Vietnamese were arrested. He replied that “it happened a long time ago. I forgot almost all of them.” She then proceeded to ask at what location he saw the arrest. He replied that the battalions were stationed close to each other, and he noticed that the two people were arrested and sent to Tuol Ta Trong. The arrest took place within his village. The children of the Khmer Rouge arrested them. “They were quite young.” The Vietnamese were arrested and walked westwards to the killing site. The young Khmer Rouge at weapons with them: they carried riffles. The hands of the arrestees were tied to their backs. They were tied up individually. “Two young cadres walked one arrested person.” He remembered: “I saw the sculls remaining at Tuol Ta Trong.” He said that he assumed that the two people were sent there. Tuol Ta Trong was near Krapeu Mountain. The arrestees were walked for around three kilometers and killed there. Ms. Chorvoin then inquired whether the children were soldiers or from a children unit. He replied that they were the children of soldiers and belonged to the cadres of Krapeu Mountain.

He heard people talk about the skeleton remains at Tuol Ta Trong. “Because once they were walked away, that would be the end of their lives.” Ms. Chorvoin asked how he knew that they were Yuon. He answered that this was “because there were some Vietnamese people living there. […] They were Vietnamese, because they spoke with accents.” He did not know anyone of those who were walked away. “I did not even know all the soldiers in my own battalion.” There were around three or four Vietnamese families in Battalion Number 2. He knew that they were Vietnamese, because “these three or four family members were arrested and walked away.”

Ms. Chorvoin then inquired how much time passed between the arrests and the time that he saw the skeleton remains. He answered that it was around two days after. “I saw the skeleton remains, as the flesh had been eaten by a wolf.” Ms. Chorvoin asked what exactly she saw and what the conditions of the skeleton remains were. He replied that he saw around four bodies and that it was likely that the people were hit and killed. “The corpses were swollen and being decomposed.” They were corpses of adults. “I could say that they were corpses of husbands and wives.”

Dead Bodies

This prompted Ms. Chorvoin to read out an excerpt of his interview.[14] He had indicated that there were dead bodies of women and children and that the heads seemed to be broken and might have been smashed against a tree trunk. She asked for his reaction. He replied that he did not witness the killing and that he did not know whether they were hit against a tree. In the extracts, he had also said that there “was blood everywhere.” She wanted to know where the blood was and how much. He replied that he saw blood stains. “I only saw it and then I fled the area.”

Mr. Koppe interjected and said that he had heard in his translation that the witness talked about “skeleton remains”, while the Prosecution asked about the “dead bodies” and that there was a difference between these two. Ms. Chorvoin stated that she had tried to clarify this issue with the witness. The witness recounted that the “bad smell was so strong that I did not dare to approach closer.”

After the arrests, there were no Vietnamese in the battalion anymore “since they all had been arrested.” He never asked Krouch about reasons for the arrests: “How could I dare to ask for reasons. They killed people without mercy, so how could I possibly ask for reasons?” He further recounted: “that group was merciless. They used us day and night.” With this, National Deputy Co-Prosecutor handed over the floor to her international colleague.

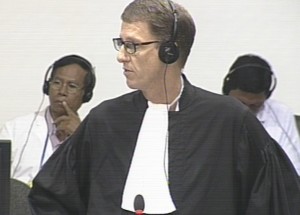

Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde inquired what happened to the Chinese in his battalions. He replied that there was no arrest of the Chinese. “Chinese were used. And sometimes, of course, they did not have food to eat.” Mr. de Wilde then asked for clarification regarding the number of Vietnamese in Battalion Number 2 and wanted to know whether it was possible that there were around 20 members in the three or four families. He answered that there were less than 20 Vietnamese – there might have been around three to four family members in each family.

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

This prompted Mr. de Wilde to ask what happened to the other Vietnamese, since he had only witnessed the arrests of two people. The witness replied that he did not know, since he did not witness what happened to them. No one told him what happened to them.

He was around ten meters away from the four bodies that he saw.

Mr. de Wilde then asked whether he saw any clothes on the bodies, which Mr. Sarun denied. The bodies were already decomposed. He did not recognize the bodies, since he was too far away. “I happened to be there when I tended the water buffalos.” Mr. de Wilde asked whether four bodies meant a “great number” of bodies or a small number, since he had testified earlier that he saw a great number of skulls. The witness replied that those bodies that were recently killed were swollen.

Mr. de Wilde inquired whether he therefore saw two kinds of bodies: bones and skulls on the one hand, and swollen recently killed people on the other. He did not count how many bodies there were. “After looking at them for a while, I walked away.” The four bodies that he saw “had been recently smashed.” The skulls remained of those people who were killed a few days ago.

The people in his battalion did not tell him that Vietnamese were enemies.

Mr. de Wilde turned to the topic of the Kamping Puoy Dam and asked about its importance. Mr. Sarun replied that the base was around 100 meters long. When Mr. de Wilde inquired whether the dam was several hundred meters long, Ms. Guissé objected on the basis that the dam was outside the scope of the trial.

Mr. de Wilde stated that this was an introductory question and would focus on the possible visit of senior leaders. Ms. Guissé responded that the visit of senior leaders would also not fall within the scope of the trial. Mr. de Wilde argued that this would help to establish the guilt of the accused and would therefore fall within the scope.

After conferring with the Bench, the President announced that the objection was overruled, since the question was related to the policy and role of the accused. However, he instructed the Senior Assistant Prosecutor to limit the questions. Mr. de Wilde then asked whether this dam was also known as the 7th January Dam, which the witness did not know. There was only one dam. He did not know about visits of the upper echelon or leaders.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Visits of Senior Leaders and Targeting of Lon Nol Officials

After the break, Mr. de Wilde referred to two documents related to visit of senior leaders at the dam site. The first one was a Radio Broadcast of 10th December 1977, which talked about the visit of the Chinese Prime Minister, accompanied by Pol Pot, Ruos Nhim (Mos Sambath) and other cadres.[15] Mr. de Wilde asked whether he was still working at Kamping Puoy worksite in December 1977, and if yes, whether the reference to the visit reminded him of something. Mr. Sarun replied that he never saw senior people visit

The second one was a book by Khieu Samphan (Recent History of Cambodia), in which he had talked about dam projects.[16]

At this point, Ms. Guissé interjected and stated that the excerpt that Mr. de Wilde had read out had “nothing to do” with the segment. Further, the question was futile, since the witness had already stated that he did not know about any visits of senior leaders. Mr. de Wilde stated that the objection was premature, since he had not yet posed the question. He then proceeded to ask whether Mr. Sarun knew at the time who Khieu Samphan was and what his role was. Mr. Sarun stated that he had not known about Khieu Samphan at the time.

Witness Prum Sarun

Mr. de Wilde then proceeded to the next topic and asked whether the cadres, such as Ta Chham, organized marriages during the period of Democratic Kampuchea. He replied that there were no marriages held during that time, but that couples were asked to hold hands and make commitments. He recounted that they knew each other and they agreed to make the commitments. “No marriages took place.” He had not participated in these marriages, since only higher ranking cadres were allowed to attend. Mr. de Wilde asked whether, since he did not participate in the meeting, he was actually unable to tell whether the couples agreed or not. The witness replied that they made the agreement.

On 17 April 1975, he saw military and soldiers who went to Au Pongmoan. There was one soldiers, perhaps he was known that he had a rank in the former regime, he was shot to death. At the time, his wife was weeping and was not moving away from her dead husband. “At the time, the wife was also shot to death.” Mr. de Wilde then asked whether he knew what the person’s name was, which the witness denied. “That person was walked past my village.” The person was walked together with a group of other soldiers. “Perhaps those persons had a rank in the former regime”, and maybe they were executed because of their role. Mr. Sarun said that Oeum was his unit chief during the time that he was a soldier. “He was smashed and killed”. At the time, he was going to collect the oranges when he encountered the decomposed body of Oeum. He was wearing ordinary clothes “and the clothes were torn, because of the dog”.

Mr. de Wilde then wanted to know whether he received instructions from Commander Kroch that former Lon Nol soldiers had to be identified and denounced. He replied that he never received those instructions. “As I said, I was a soldier in the former regime.” This prompted Mr. de Wilde to refer to the witness’s interview. He had stated that they sought to eliminate high ranking soldiers of the former regime.[17] Mr. Sarun replied that “I said nothing when I was asked by him. I replied that I did not know who had ranks.” However, the high-ranking officers “were taken away and smashed.” He gave the example of Ta Oeum.

Mr. de Wilde then inquired what the high-ranking officials were told to convince them to go with the Khmer Rouge cadres. Mr. Sarun replied that he did not know how to answer that question.

Mr. de Wilde moved on and asked whether the family members of those officers and soldiers also targeted, which the witness denied. “Family members had never been arrested and sent away.”

Mr. de Wilde then turned to the statement by Chuck Pounlok, who had talked about the execution of Lon Nol soldiers. Mr. Sarun did not know this person.

In this statement, it had been indicated that subordinates of Ta Chham arrested chiefs and teachers, amongst them Klaut Chhan.[18] Mr. Sarun replied that they gathered high-ranking cadres at Wat Phnom Sampeou.

Judge Claudia Fenz

Mr. Koppe interjected and stated that open questions should be asked first and not read out excerpts first. Judge Fenz inquired whether Mr. Koppe wanted to prohibit any question. Mr. Koppe replied that he “was sure” that the next question would be to give a reaction. Mr. de Wilde proceeded and asked whether the witness remembered such a gathering as mentioned by another witness, which Mr. Sarun denied. Mr. de Wilde then asked whether Mr. Sarun knew Klaut Chhan and what happened to him. The witness replied that he was the commune chief and also taken away and killed.

Mr. de Wilde asked whether the witness remembered the period when Klaut Chhan was killed. Mr. Sarun replied that he was killed “when they investigated” and found out that he was the commune chief.

Mr. de Wilde further asked whether Mr. Sarun feared for his life under the Democratic Kampuchea regime. He replied that he “was also afraid, but I worked very hard.” For this reason “they kept me.”

Mr. de Wilde then inquired about the person Ta Daok who had been killed and wanted to know what the reason was for the killing of this person. Mr. Sarun replied that the reason was “that he had a gun.” He had probably been a Lon Nol soldier. He hid his gun. He recounted that the people went to a high school for a meeting and that these people were smashed, meaning to be killed. “They said that he had a gun” and that he had dared to challenge them. “I witnessed the execution of him, because I also attended the meeting. One of his children was also killed along with him.”

He recounted that Sambath came to Phnom Sampeou once to chair a meeting once. However, he did not see his face clearly, since he was far away. In this meeting, they told him to work hard and did not speak about ideology.

At this point, the floor was granted to the Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang. He asked why they used the military terms platoon and company to ordinary people. The witness replied that he did not know about the reason. “I just followed what people said.”

Moving to his next question, Mr. Ang asked whether it was true that he lived in Krapeu Cheung Village, which the witness confirmed. Mr. Ang asked whether he knew if Vietnamese lived in the neighboring village, which the witness did not know. He never went there.

Mr. Ang asked whether there was a stream at Tuol Ta Trong, which the witness confirmed. Tuol Ta Trong was to the east of the stream. He did not know whether the people were killed at the small stream. He then read out an interview of a monk.[19] The witness replied that some people might have died because of hunger.

Mr. Ang then inquired whether the witness was able to talk about the period from 1976, 1977 and 1978 and asked whether there were any Khmer Krom living in this area or adjacent regions. He replied that they were neither living in Banan commune nor in adjacent villages.

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

When Mr. Ang started asking his next question related to the killing of Khmer Krom,[20] Mr. Koppe interjected and stated that the killing of the Khmer Krom was outside of the scope of the trial. Ms. Guiraud clarified that the Civil Party interpreted the scope differently. While it had been clear in the oral ruling of 25 May that the treatment of the Khmer Krom as a specific group was not included, the treatment of the Vietnamese clearly did fall under the scope of the trial.[21] Thus, Khmer Krom should not be excluded as such. After conferring with the bench, the President announced that the objection was upheld.

Mr. Ang inquired how the witness could hear the accents of the Vietnamese people in the other battalion who were taken to Tuol Ta Koy to be killed. Mr. Sarun stated that he did not talk to them and had not said anything about their distinct accents. He further said that “I never said they were taken to Tuol Ta Koy to be taken away to be killed.”

Mr. Ang asked whether the witness ever said that there were a few Vietnamese people being taken away from Battalion 2, which the witness confirmed. They were taken away and killed at Tuol Ta Trong. He then said that the Vietnamese spoke with accents and were taken away for this reason. With this, Mr. Ang finished his line of questioning.

The President adjourned the hearing. It will resume tomorrow, December 12 2015, at 9 am. Witness 2-TCW-929 will be on the reserve.

[1] D22/3175/1, at 00561343 (EN). [2] During the last session, Mr. Koppe insisted repeatedly on not using this term and therefore uses it with quotation marks. [3] E3/1852, at 00818933 (EN), no other language available. [4] E3/5631. [5] E3/5631, at 00898372 (KH), 00897513 (KH), 00678292 (EN). [6] E3/6695. [7]At, 00561350 (KH), 0106664 (EN). [8]E3/5631, at 00898372 (FR), 00897514 (KH), 00678292 (EN). [9] E3/6695. [10] E3/5631, on p. 1 in all languages. [11] There was some confusion about his birth date. He first indicated being born in April 1955, but confirmed the President’s question of being born in January 1942. He claims being 74 years old. [12] E3/5187, at 00197916 (KH), 00274177 (EN), 00274184 (FR). [13] E3/5187, ibid. [14] E3/5187, at 00197916 (KH), 00274178 (EN), 00274185 (FR). [15] E3/1339, at 00168342 (EN), no other language available. [16] E3/18, at 00595487 (FR), 00103780 (EN), 00103878 (KH). [17] E3/5187, p. 4 (FR), 3-4 (KH), 4 (EN). [18] Page in English and French, pages 2-3 in Khmer. [19] E3/7232, at 00197883 (KH), 00274160 (EN), 00226156 (FR). [20]E3/5185, Oum Cheoun 00197889 (KH), 00274166 (EN), 00226163 (FR). [21] E1/304.1.

Featured Image: Witness Prum Sarun (ECCC: Flickr)