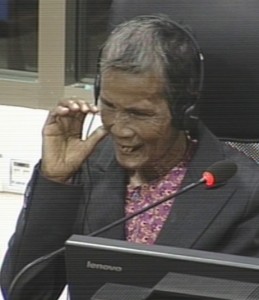

Wife of Former Commune Chief Testifies

Sin Chhem, the wife of a former commune chief, testified today. While she knew a few people that seemingly were high-ranking cadres, she could not shed much light on the existence of a plan to overthrow the Pol Pot government. She stressed that no information was given to her, since she was a woman, and that she had a poor memory.

Family ties

At the beginning of the session, the Trial Chamber Greffier confirmed the presence of the parties, with the exception of Judge Claudia Fenz.

Witness Sin Chhem was born in Svay Yea Village, Svay Yea commune, Svay Chrum District in Svay Rieng Province, where she also currently resides. The International Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak opened his line of questioning by inquiring about the time that the Khmer Rouge took power in her district. She could not remember the date. “I could only remember the Khmer Rouge killed a lot of people.” She could only recall the year 1975. Asked whether it was in Svay Chrun district or in Meanchey Thmey district, she said that it was located in the former. She did not know the Sector number. There were around 100 families in her village. There were around three or four Vietnamese families. She was assigned to transplant rice sometimes.

Mr. Lysak inquired about her brother Sin Chhuon. She did not know his position. In the old regime, he was also a rice farmer. During the revolution, he “also joined it” and stopped transplanting rice.

Mr. Lysak referred to her brother’s S-21 biography, which indicated that he was born on October 28 1940 in Svay Yea Village and that he had four siblings.[1] Based on this biography, Mr. Lysak asked whether she had a younger brother who worked as a medic and what his name was. She replied that his name was Sin Chhouk. He was located at a pagoda during the Khmer Rouge regime. Mr. Lysak asked whether this was the Sector 24 Hospital, to which she replied that it was indeed located in Sector 24.

Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak

Her brother had indicated that he joined the revolution on 26 October 1970 and mentioned someone called Chakrei. Asked about this person, she replied that she did not know him and only heard his name from her brother. She confirmed that he was a military chief in the district.

At this point, Mr. Koppe had a request for clarification. Earlier, the Co-Prosecution had asked whether her village was located in Sector 23, while the biography of the witness’s brother talked about Division 24. Mr. Lysak referred to document E3/2010, in which the part on Sector 23 indicated that her village was located in that sector. His understanding was that her brother worked in Sector 24, while she lived in Sector 23.

Turning back to Ta Chakrei, Mr. Lysak inquired how her brother knew him. She replied that they were friends and worked together. In her statement, she had identified Ta Chhouk, Kev Meas and Ta Thoch as three people who her brother knew. Mr. Lysak asked how her brother knew them. She replied that they were her relatives and lived close to her house. Mr. Lysak said that she had indicated in her interview that Kev Meas, while the other two lived in her village. He wanted to know how Kev Meas was related to her. She answered that Kev Meas “belonged to her cousin.” Ta Chhouk was her brother’s teacher. “He was a very good person.” She did not know which position he held, she only knew that he was killed. Asked whether he was the chief of the sector, she replied that she could not recall. She did not know the position of her cousin Kev Meas either.

Mr. Lysak asked where her brother was stationed between 1970 and 1975 and whether he engaged in combat with the Lon Nol army. She replied that she only knew he worked in Sector 24. “Later on I heard that he was killed.” She saw her brother when he came to her sister’s wedding. She also went to see him once. She could not remember when she went there.

Mr. Lysak referred to her DC-Cam interview, in which she had said that her brother was chief of the Sector 24 army in Ba Phnom District.[2] She confirmed this but said she could not remember.

Mr. Lysak turned to her husband Tieng Phan. She could not remember when she married him, but it was during the Khmer year of dragon. Her wedding was based on Khmer tradition and “not the revolutionary way.” He became the chief of Svay Yea commune in 1976. She did not know who appointed him. She said she should not work in that position, since “it could be dangerous.” She could not remember the name of her husband’s supervisor. Mr. Lysak said that she had indicated in her DC-Cam interview that Khieu Samit was the chief.[3] Hearing this name, she said that she could remember now – he was indeed the chief.

Mr. Lysak inquired what happened to her brothers Sin Chun and Sin Chuk. She replied that they died. “They were taken away and killed. I did not know where they were killed.” Mr. Lysak asked whether she remembered what year it was that brother and husband were taken away and killed. She replied that her husband was taken away in late 1977, but her older brother was taken away earlier. Mr. Lysak inquired how she learned that her older brother had been taken away. She replied that Sym, a member of the commune committee, told her so. He did not tell her the reasons.

Mr. Lysak asked whether she remembered what happened to Chakrei, Kev Meas and Ta Chhouk. She replied that she did not know what happened to them. Later she had learned that he was killed. A person who worked at the commune level told her so.

Mr. Lysak referred to her interview in which she had indicated that Ta Chakrei and Ta Chhouk had been arrested and killed.[4] Mr. Lysak asked whether she remembered being told about the arrests of Chakrei and Ta Chhouk by her husband. She replied that she forgot about that. “However, it did happen at the time. I was afraid upon hearing that.” Her husband always reminded her of being “very careful” and to focus on work.

Her older brother was arrested first, then Ta Chhouk, and then Chakrei. She said that she could recall the exact date earlier, but not now anymore. Mr. Lysak referred to her statement and said that her older brother was arrested one month after Hou Nim’s arrest.

Mr. Lysak referred to the OCP Revised S-21 list, which recorded that the Sector 24 Secretary was arrested on August 28 1976, followed by Kev Meas on September 20 1976 and Hou Nim in April 1977.[5] Mr. Lysak said that this would put the arrest of her older brother at around mid-1977. He asked whether this was correct or whether it was earlier or later. She replied that her older brother was arrested at the early part of the year, while her husband was arrested in the later part of the year.

Mr. Lysak then wanted to know what happened to her older brother’s wife and children when he disappeared. She replied that “nothing happened to them. Even his wife didn’t dare to cry.”

Mr. Lysak referred to her DC-Cam interview in which she had that her older brother’s wife and children had been sent to Pursat.[6] The wife is still alive today, but two of her children passed away.

Referring to the arrest of Kev Meas of September 1976, Mr. Lysak asked whether she knew if any Kev Meas family members were also arrested. She replied that the teacher Thoch had a niece. He repeated his question. She replied that she did not know about his wife. She knew that they had children, but she did not know about their fate. She knew that he and his younger brother Khoch, who had a daughter, was taken away and killed.

Arrests

After the break, Mr. Lysak resumed his line of questioning and asked whether anyone had told her why Kev Meas had been arrested. She replied that she did not know. Mr. Lysak then referred to a book about Nuon Chea by Thet Sambath, in which it had been submitted that Kev Meas had been arrested, because he had been living in Vietnam.[7] Mr. Lysak inquired whether she knew who Nuon Chea was and whether she knew anything about Nuon Chea’s responsibility in her Kev Meas’s arrest. She replied that she did not know.

Next, Mr. Lysak inquired how she had learned that her husband had been taken away and arrested. She replied that she received the news while she was working. He was taken away somewhere near Svay Rieng. The person who took him away was called Ao. She did not know where he was from, but he was a security guard. All other commune chiefs and others were also arrested at that time. They were said to be re-educated, but disappeared ever since. She never saw her husband again after he was taken away. She only heard that someone told her that he would be sent back to Yea village, but she never met him again.

Mr. Lysak turned to the next topic and asked what happened to the Vietnamese people during the Khmer Rouge regime. She replied that those who had Vietnamese wives and children, their wives would be taken away and killed. “I felt pity for them. At least they should have kept the children alive.” The children were also taken away and killed. “It was so brutal”, she recounted. Four families were taken away. These families lived near her house – around a kilometer away – and were also members of the commune committee. Those Vietnamese families were taken away before her husband was arrested. She remembered: “They whole family was killed, including the children.” Someone replaced her husband and he was the one who collected the Vietnamese families. Mr. Lysak asked for clarification when the Vietnamese were arrested: did it happen while her husband was commune chief or when he had been replaced? She replied that it took place after her husband had been replaced. “My husband had nothing to do with this.”

Mr. Lysak then inquired whether there had been a meeting about what to do with mixed Khmer families. She replied that she never attended meetings, “because I was not allowed to attend the meetings.” Mr. Lysak asked whether she had heard about a meeting held by the new cadre, and whether it had been announced what to do with the Vietnamese people. She replied that she did not know.

This prompted Mr. Lysak to read an excerpt of her statement, during which she had said that the Khmer Rouge cadres announced that if a Khmer husband was married to a Vietnamese wife, both the wife and child had to be taken away.[8] She replied that they had said that those children that had been breastfed by their mothers had to be killed. Someone called Savun told them so. Savun participated in the killing and was secretary guard for the new commune committee. Savun was “part of the new team. So he is the daring person who participated in the killing.”

Mr. Lysak then proceeded to refer to her OCIJ interview, during which had told the investigators that the ethnic Vietnamese people were arrested and killed after the arrival of the new cadres.[9] She had recounted about killings of ethnic Vietnamese in the villages Tuol Vihear, Sykar and Kien Ta Siev. He asked who told her about these. She replied that “people who were close to [her]” told her so. She forgot the names of those, but they lived close to her house.

Mr. Lysak then asked how Vietnamese people were identified. She replied: “I did not know who was red, who was white.” When Mr. Lysak repeated the question, she said that she did not know. Some Vietnamese people were forced to return to Vietnam, but later on returned to Cambodia “to do business.”

Mr. Lysak turned to his next topic and asked what happened to the next topic and asked what happened to those who were former Lon Nol officials. She replied that she did not know much.

Mr. Lysak read out an excerpt of witness Sarun from her district, who lived in Klork Commune and who had testified that biographies were taken before people were taken to Langnoeun Pagoda and killed.[10] Ms. Chhem confirmed knowing this pagoda and said it was located near Dangsoeun. When Mr. Lysak inquired what this pagoda was used for during the Khmer Rouge, Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé objected on the basis that Langnoeun Pagoda was not included in the severance order. Mr. Lysak replied that the evidence suggested that Lon Nol soldiers had been killed there and that his could be used to establish a national policy. Mr. Koppe submitted that Kiernan had indicated that Lon Nol soldiers in the East Zone were re-educated for around three months before

Anta Guissé submitted that the defense had not been notified of these new elements. This might constitute a “blatant violation of the rights of the accused.” After conferring with the bench, the President gave the floor to Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne. He announced that the objection was rejected, since the question related to the policy. Questions that went into too much detail would be prohibited.

Mr. Lysak resumed his questioning and asked whether she remembered Lon Nol soldiers being taken to the pagoda. She replied that she did not remember.

Mr. Lysak then inquired whether she knew who Khieu Samphan was at the time and whether she remembered him coming to her district. She replied that she only knew Hou Yun and Hou Nim who came to her area in 1976.

The same witness had referred to someone called Khieu Samit.[11] Mr. Lysak asked whether she knew if Khieu Sammit was a relative of Khieu Samphan. She replied that she did not know whether they were related. She only knew that he came to her area.

Mr. Lysak then asked whether she remembered any leaders from Phnom Penh coming to the dam she worked at. She replied that only Hou Nim and Hou Yun came to her area. She did not know about anyone else.

Turning to her DC-Cam statement, in which she had said that “Khieu Samphan was so skillful with the Khmer Rouge” before killing and making people terrified, Mr. Lysak asked whether she remembered having said this and if yes, whether she could explain the meaning.[12] She replied that she only knew that Khieu Samphan, Hou Yun and Hou Nim were part of the leaders. “And later on, Khieu Samphan joined the enemy site.”

International Deputy Co-Proseuctor Srea Rattanak

At this point, Mr. Lysak handed the floor to his national colleague Srea Rattanak.

Mr. Rattanak inquired what happened to the Khmer husbands of the Vietnamese wives and asked whether these were forced to remarry. She replied that the Khmer husbands did not marry again. She never saw the Vietnamese wives again, which Ms. Chhem denied: “They were gone forever.”

The Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers did not have any questions for the witness.

The President granted the floor to the Nuon Chea Defense Team. International counsel Victor Koppe turned to her cousin Kev Meas and asked the witness whether she could give more details about this person. She replied that she only remembered his younger brother Thoch. Kev Meas rarely stayed in the village. Before this, he was in Cambodia. He tried to flee, but “ultimately, he was arrested and killed.” Mr. Koppe asked whether he Kev Meas was often in Vietnam before 1975. She replied that she did not know about this. She had heard that he was earning his living in Phnom Penh. She had never heard that he lived in Vietnam. “I only heard that he was living near a market in Phnom Penh.”

Mr. Koppe asked whether her cousin was involved in joining the revolution already in 1951. She replied that she knew that he and her older brother joined the revolution, but did not know when. “Because at a woman, I usually stayed at home and did not know the affairs they were involved in”, she recounted. Her older brother told her that he and her cousin joined the revolution at the same time. Mr. Koppe asked whether it might have been in the early 1950s, to which she replied that it might have been 1975. When Mr. Koppe pressed on, she insisted that she could not remember.

Mr. Koppe asked whether she had ever heard that there had been two communist parties in Cambodia. She answered that she only knew about the revolution. She offered explanation for her lack of knowledge: “In the past, I remembered well, but not now.” Mr. Koppe inquired whether her older brother, her husband, her cousin or the commune chiefs ever talked about the existence of two communist parties. “As I said, I was a woman, and I was young, and they did not tell me anything about that affair.”

Mr. Koppe asked whether Chakrei had a more senior position to her older brother, which she confirmed. She said that her brother was probably one rank below Chakrei.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Leadership

After the break, the floor was given again to the Nuon Chea Defense Team, who resumed his line of questioning. Mr. Koppe requested leave to present to the witness a still from a East German documentary called “Die Angkar”, as indicated earlier in an e-mail to the legal officers today. Mr. Koppe asked whether she recognized the person on the photo. She said that it looked likely like Kev Meas – he had a similar beard – but she was not entirely certain. The eyes seemed different. Mr. Koppe then requested leave to present two minutes of the footage.[13]

He explained that the original language was in German, but that he had provided the transcript of the German voice over and an English translation. Co-Prosecutor Dale Lysak said that this was not an official translation and that it should also not be on the record as such. Mr. Koppe agreed to this. The extract of the documentary was shown. It showed the leadership of Democratic Kampuchea and argued that the party was divided into two parts. It showed portraits of several high-ranking cadres and mentioned a cadre called Keo Mony, who was member of the central committee.

According to Mr. Koppe, Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea can be seen in this video footage.

Judge Lavergne asked when this documentary was produced. Mr. Koppe replied that it was produced by two renowned German filmmakers in 1981. Asked about a person at the end of the footage, she said that the person on the photo was her uncle. When asked about further persons, she neither knew Son Ngot Minh, nor Kev Mony.

Mr. Koppe referred to an internal battle of the communist party that the documentary had mentioned and asked her whether she had heard about this. She replied that she knew at the time, but not now anymore.

He then referred to an interview of Heng Teav, who had a senior position in the government of Heng Samrin in 1985 and before and was the second person known as Ta Pet. He had talked about two strings of the party, lead by Song Ngot Minh and Thou Samout.[14]

At this point Mr. Lysak stated that the excerpts were misleading, since the witness later indicated that Song Ngot Minh died in 1972 and Thou Samut died in 1962.

Mr. Koppe insisted that he should be allowed to put this question to the witness, since Heng Teav held a senior position in the government.

After deliberating with the bench, the President gave the floor to Judge Lavergne. He explained that it did not concern the time period that the Court was dealing with.

Mr. Koppe moved to another document, namely the testimony of Ban Siek, who had been a North Zone District chief and who had testified on October 5 2015 and October 6 2015. He had submitted that there were two communist parties, namely the Communist Party of Kampuchea and the Workers Party.[15] She replied that she had never heard about this.

Mr. Koppe proceeded to ask about another document, which stemmed from the People’s Revolutionary Tribunal of August 1979.[16] This document, according to Koppe, listed the top men of the Democratic Kampuchea Workers Party, namely

- Sao Phim, committed suicide 3 June 1978.

- Ta Nhim, arrested in June 1978

- Kev Meas, arrested in September 1976.

Ms. Chhem said that she did not know anything related to Sao Phim.

Mr. Koppe then referred to David Chandler’s book on S-21, who had stated that Kev Meas, together with Nuon Sun, had “operated in the open”, and that Kev Meas had twice run for the National Assembly as a radical candidate.[17] Mr. Koppe asked whether she remembered this. She replied that she did not know about that. He was rarely home. However, in the past his father was chief of the district. Mr. Koppe asked whether Kev Meas worked in Beijing on behalf of the United Front Government in Exile, which she denied. She said that he lived in Phnom Penh. Mr. Koppe asked whether she was certain that he did not work for the United Front Government in Exile, which she denied.

Mr. Koppe said that her cousin Kev Meas was put under house arrest when he returned. Ms. Chhem replied that he heard that he was relocated from Phnom Penh to go elsewhere and later arrested and killed. Mr. Koppe asked whether she had heard anything about the house arrest, which she denied.

Mr. Koppe moved to the next persons, namely Chhouk and Chakrei. In the minutes of the meetings of secretaries and deputy secretaries of divisions and independent regiments of October 9 1976, Son Sen was talking to the military.[18] Kev Meas, Chhouk and Chakrei were mentioned in connection to a plan from the East Zone to attack Democratic Kampuchea. Mr. Koppe asked whether she had ever heard about such a plan. She replied that she had heard about it, but that she forgot the details about such an event. Chakrei and Chhouk frequently came to her house to meet her brother. She did not know what they discussed, “since I was a woman.” She told the Court that the men discussed their matters in secret, since “a woman would spread the rumour”.

In her brother’s testimony, he had said that Chan Chakrei was his friend.[19] She said that her brother knew Chakrei.

Mr. Koppe referred back to the minutes of the meeting, which show that Son Sen spoke about events that Chakrei was involved in together with other people, including firing guns, throwing grenades and distributing leaflets in front of the Fine Arts College near the Royal Palace. She said that she did not know. “I knew about the later stage when they started killing people.”

Mr. Koppe then referred to another document, which had talked about a rebellion and the arrest of people.[20] Mr. Koppe asked whether what he was reading was “completely unknown” to her or sounded somehow familiar. She said that she did not know. “And let me repeat: What I know is that the Pol Pot regime killed people.” Mr. Koppe asked whether they were arrested, because they had been involved in a coup d’état. She replied that she did not know anything about that. “I only knew that he worked and later on he was arrested.” Mr. Koppe asked whether her husband had ever told her about the reasons for the cadres’ arrests, which she denied.

He asked whether any of the other names – such as Lea Penh, Ruos Punh, Lea Vay (Dep Sec 170) – sounded familiar. This Australian author had indicated that Chhouk had been a long-time protégée of Sao Phim. She replied that she did not know.

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Her brother had said that he joined the revolution in 1970 having been introduced by Chakrei.[21] Mr. Koppe asked whether it was indeed Chakrei who introduced him to the revolution. She replied that she knew that Ta Chhouk was a leader. Only later on did she learn that Chakrei was a friend. Ta Chhouk taught her older brother. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that all five of them – Kev Meas, Kev Theuk, Chakrei, Ta Chhouk – and her brother were all very close to each other, which she confirmed.

Her brother had spoken about American imperialists and Lon Nol traitors. Mr. Koppe asked whether she could explain what her brother meant with this. She replied that she did not know, since the people were only discussing amongst themselves. When Mr. Koppe repeated this question, Mr. Lysak stated that Mr. Koppe had already asked the question and that if she was to answer the question, she would have to speculate.

Mr. Koppe rephrased the question and asked whether she knew if her brother was involved in arrests and possible killings of Lon Nol officials, which Ms. Chhem denied. “They were far from me.”

Mr. Koppe moved on to the next topic. Mr. Koppe asked her to describe her activities between 1975 and 1979. She replied that she had to work hard wherever she would be assigned to. Her husband had advised her to work hard and not to talk, so she followed the advice. During the day, she would have to work from 7 am until 5 pm. There was a one-hour lunch break at noon. She dug a canal to the east of Svay Chrum Pagoda. She worked there from 1977 onwards. Later, her husband was arrested. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that she was “just an ordinary worker” while her husband was in charge of the district. He asked whether she was part of the commune or district forces or part of the mobile forces. She replied that she was in no unit. “I was simply assigned to do the work.”

Mr. Koppe asked whether there were also New People in her district while working under her husband, and whether there was any difference between them. She replied that she worked with them. “They never said anything to me and I also never said anything to them. We were like friends. We did not blame each other during our work.” They received the same food rations. They also had the same work hours and the same medicine.

Mr. Koppe asked whether he was right to say that New People and Base People were treated the same in her commune, which she confirmed. She estimated that they started eating communally five months after the arrest of her husband.

Her husband “did not order any arrest of people. He loved people”. Mr. Koppe then asked whether Vietnamese people worked at the rice fields and the dam when her husband was in charge, which she confirmed.

Traitors

In the last session, Mr. Koppe took the floor again.

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne

He said that she had made a distinction between the Khmer Rouge and the “traitors of the nation” and asked what this meant.[22] Mr. Lysak interjected and stated that she clarified that she had talked about Pol Pot betraying and killing people.

Mr. Koppe said that the page before indicated she in fact talked about two different groups.[23]

Judge Lavergne read out a longer excerpt, in which she had indicated that Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge were the same group. After a small discussion, Mr. Koppe asked the witness whether she had referred to two groups: the Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot and the traitors on the other. She replied that she could not remember well. She remembered that the Khmer Rouge killed the people, and not the party.

Mr. Koppe asked who she then referred to as the “traitors of the nation”, she replied that they were killed, because they were being accused of being traitors.

Treatment of the Vietnamese

Mr. Koppe returned to the mixed-Vietnamese families in her commune and asked whether she knew their names. She said that they were her relatives on her mother’s side. She said that her mother and “his wife” were cousins. The husband was pure Khmer. The Vietnamese wife was his second wife, since the other had died before. She did not know whether this person held a Vietnamese or Cambodian passport.

She did not witness killings, but some people were buried to the south of her house. She saw the remains of the dead bodies and was told that they had been killed the night before. “Actually the dog uncovered the burial site and ate the corpses. I saw the scattered of the remains as well as the clothes.”In that pit, there were the wife, the husband, and the two children.

She had heard about Vietnamese people being sent to Vietnam, but she was not sure whether they were actually sent back. She saw the arrests. “They were ordered to run in front of a bicycle.”

Mr. Koppe asked whether Ms. Chhem had ever heard “the sound of battle”, such as grenades, which she confirmed. There were sounds of shelling. “I was so frightened. And we were running to take refuge. Actually, when we heard the sound from the shelling, I took my younger children and ran to seek refuge in another village.” The shelling came from the direction of Vietnam. “There were two groups: one was good and one was bad.” There was a good Vietnamese group. Since she was smiling when saying that, Mr. Koppe asked what made her smile. She said that this was because that was what people said.

Some people were injured from the shells. Her nephew was hit in the neck, but another Vietnamese group came by and treated him. He was sent to Vietnam for surgery. The shelling took place in early 1977. She saw tanks and Vietnamese troops who engaged in a battle. Some Vietnamese soldiers came to her house and ate there. “And they actually made cakes for us.” Khmer people arrested the Vietnamese – it was not the Vietnamese army who arrested the Vietnamese. Mr. Koppe clarified that he asked whether the incident with the bicycle happened after or before the Vietnamese troops entered Svay Rieng. She replied that it happened afterwards.

There were many soldiers who came to her village. “They did not mistreat us at all. Actually, they were part of a convoy walking through our village.” Sometimes the troops would cook rice at their place. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was possible that they left again around January 6 1978. She replied that she could not recall the year. Mr. Koppe then asked how many months after the arrest of her husband the Vietnamese went back to Vietnam. She replied that they returned before her husband’s death. “After they returned, the people started to be arrested and killed.” She did not hear about her husband being accused of collaborating with the Vietnamese. “I survived because of the Vietnamese liberation,” she said. “So I admire them. I do not feel angry with them.” She denied that people were accused of collaborating with the Vietnamese. With this, Mr. Koppe

Witness Sin Chhem

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé asked whether she was sure that the Vietnamese people cooked food for them during the Democratic Kampuchea regime. Ms. Chhem replied that she was not sure about the year. Ms. Guissé stated that she had described a similar occasion, but during the fight against the Americans and Lon Nol.[24] She read out an excerpt and asked whether what she had described earlier had not in fact then. The witness’s answer did not shed much light on the matter. Pressed on this matter, the witness replied that there seemed to have been different groups. Ms. Chhem could not recall when this took place. When Ms. Guissé repeated the question whether this was during the Lon Nol regime, Ms. Chhem replied that it took place later. When Ms. Guissé asked whether it took place before 17 April 1975, the witness could not answer the question. She recounted that 1975 was chaotic, in 1976 and 1977 they ate communally, and in 1978 and 1979 the country was liberated.

Turning to another topic, Ms. Guissé inquired about the arrest of Vietnamese people in her village. Ms. Chhem replied that she had not seen the arrest of Vietnamese people. The people who she saw running in front of a bicycle and arrested were Khmer. Ms. Guissé referred to her DC-Cam interview.[25] She had said that the people who were arrested were village chiefs. She replied that the people who were arrested were ordered to run ahead of the bicycle and beaten.

Ms. Guissé then asked about her sister-in-law. Ms. Chhem replied that she later returned, but that two of her children died. The children died after the Democratic Kampuchea regime. “One of them hung herself and another one died just about two years ago.”

Ms. Guissé asked about the Tuol Vihear village.[26] The witness replied that it was around 1.5 hours away from her own village. Sykar village was around a kilometer away. Kien Ta Siev was also around a kilometer away from her village. She frequently went there to buy food. “Those people in the village were arrested and taken away.”Ms. Guissé asked when she went shopping and bought things for herself. She replied that she used rice to barter it for food. She did not witness those arrests herself. The people who told her were ordinary people. “They saw the arrests and told me.” The people who were arrested were taken to be killed. She was also told about the execution site. The house of the people who told her was located next to the house of the Vietnamese people. “The next people they told me ‘oh those Vietnamese family [was] arrested and taken away.’”

Turning to her last line of questioning, Ms. Guissé asked whether it was true that she never met Khieu Samphan during the Khmer Rouge regime, which the witness confirmed. She only heard later that he escaped to join the “Pol Pot group”. Asked when this happened, she remembered that this was “from the beginning.” The enemy she had referred to in her interview was Pol Pot. She could not tell whose enemies they were.

Hou Yun and Hou Nim came to do rice farming in the dry season. Later, she heard about Khieu Samphan having joined the Pol Pot group. With this, Ms. Guissé finished her line of questioning.

The President thanked Ms. Chhem and dismissed her. He then adjourned the hearing. It will resume tomorrow, Tuesday, December 15, with witness 2-TCW-846.

[1] E3/7526, at 00079576 (KH), 00324095 (EN), 00728266 (FR). [2] E3/7526, at 00746949 (FR), 00185370-71 (EN), no English translation available. [3] E3/7526, at 00746966 (FR), 00185388 (KH), no English translation available. [4] E3/7794, at 00249916-17 (KH), 00251405 (EN), 00285545 (FR). [5] E3/342. [6] E3/7526, at 00746950 (FR), 00185372 (KH). [7] E3/4202, at 00858339 (KH), 00757531 (EN), 00849435 (FR). [8] E3/7794, at 00249918-19 (KH), 00251407 (EN), 00285548 (FR). [9] E3/7794, at 00249918 (KH), 00251407 (EN), 00285547 (FR). [10] E3/7719, at 00344565-66 (KH), 00347416 (EN), 00411563 (FR). [11] E3/7719, at 00344567 (KH), 00347418 (EN), 00411565 (FR). [12] E3/7526, at 00185385 (KH), 00746963 (FR). [13] E3/3095R (also listed as E3/719R), minutes 13:31-15:49. [14] E3/5309, at 00388327 (KH), 00426128 (EN), 00479776 (FR). [15] E1/354.1, at 9:45. [16] E3/7327, at 01113795. [17] E3/1684, p. 54, at 00192733 (EN), 00191890 (KH) 00357321 (FR). [18] E3/13, at 00052406 (KH), 00943043 (EN). [19] E3/7526, at 00746949 (FR), 00185371 (KH), no English translation available. [20] E3/1784, at p. 52, at 00192731 (EN), 00191888 (KH), 00357319 (FR). [21] E3/7526, at p 1 00079567 (KH), 00728260 (FR). [22] E3/7526, at 00746962 (FR), 00185384 (KH). [23] E3/7526, at 00746961 (FR) 00185384 (KH). [24] E3/7526, at 00746954 (FR), 00185376 (KH). [25] E3/7526, at 00746963 (FR), 00185386 (KH). [26] E3/7794, at 00285547 (FR), 00251407 (EN) 00249918 (KH).