Instructions to Kill Vietnamese People

After a two-week break, the Trial Chamber opened the first hearing of 2016 today, January 5 2016, in front of the ECCC. Anonymous witness 2-TCW-1000 continued and concluded his testimony of December 16 2015 and testified on issues such as the chain of command as well as the so-called Mayaguez incident that took place in 1975. The incident was a clash between an American vessel and the Cambodian troops. The witness also put forward that the orders to kill Vietnamese combatants and civilians came from the upper echelon, an allegation that Nuon Chea Defense Counsel challenged. At the end of the day, witness Theng Phal – also known as Theng Huy – provided information on people who lived in his birth village.

Combatants in Kampong Som

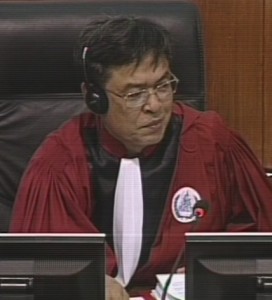

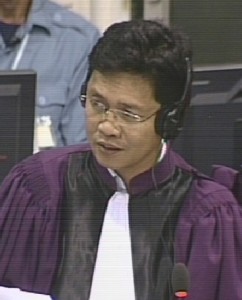

At the beginning of the session, the Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn announced that the remainder of 2-TCW-1000’s testimony would be heard and that 2-TCW-848 was on the reserve. He further stated that Ya Sokhan was absent for personal matters and was replaced by Judge Thou Mony. The Trial Chamber Greffier then confirmed the presence of all other parties, with the exception of Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé and standby-counsel Calvin Saunders, who were absent due to personal reasons. Nuon Chea followed the proceedings from the holding cell.

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

The President then stated that the floor would be given to the parties tomorrow to discuss the requests by the Co-Prosecution and the defense. He then announced the oral decision on the request by the Khieu Samphan team to admit four documents of 23 December 2015 to question 2-TCW-1000; the documents were admitted.

The floor was then granted to Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe, who wished the courtroom a happy new year first. Mr. Koppe then asked whether it was 1973 that the witness joined the revolution as he had indicated earlier. The witness replied that he joined the revolution on May 02 1972 in Kampot. Mr. Koppe asked what the witness did in the years until 1975. He replied that he was a messenger in a platoon. He said that his battalion supervisor was Ta Mon. He was Ta Mon’s personal messenger between 1972 and 1973, after which he was “sent to the Zone” by Angkar. In 1972, he worked in Kampot area. In 1973, his battalion was sent by Angkar to Dak Kuoncho, after which they advanced to Phnom Penh. In 1974, he was with the artillery unit. Asked about his functions there, he said that he was “simply a combatant.” They fought against the Lon Nol soldiers. There was one company in his battalion and other armed units with different kinds of ammunition. He was with the artillery unit that had the DK-81 canons. When asked whether he also commanded people, he replied that he was “merely a combatant” who received orders through the chain of command. He was with the artillery unit until 1975 when Phnom Penh was liberated, after which he was assigned to work in Kampong Sao.

Mr. Koppe pressed on and asked whether he never gave orders to anyone in these years and only received orders, which the witness confirmed. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that there were never any combatants below him even after 1975, which the witness confirmed.

Mr. Koppe then inquired whether he had ever handled guns that had 12.7 millimeters ammunition. He replied that he had heard of this canon, but it was usually used on a ship and not on land. When being in the artillery, he used to fire the 17 or 18 millimeter guns. He used to fire the 12.7 millimeter gun. He arrived in Kampong Som around three days after the liberation. He went to Koh Tang Island afterwards, but he could not recall the date.

The Mayaguez Incident

He confirmed that there was an incident in 1975. The ship Mayaguez was intercepted and there was intensive fighting. This ship belonged to America and the crew was American. The American people got onto an airplane and left the place. There was also aerial fighting at the time. In 1975, the infantry had no ships and boats. He did not know which group captured the Mayaguez. There was an order from the division and they went to capture the boat.

Mr. Koppe asked whether it was another group than his group, maybe called the PCF-group. The witness denied this and explained that the PCF was a slow boat. “We used mine sweepers” to arrest the boat.

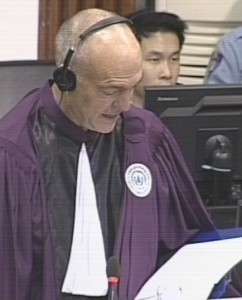

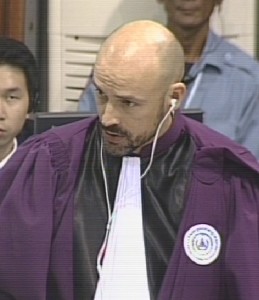

Judge Claudia Fenz

Mr. Koppe then referred to one of the witness’s statements, in which he had said that the PCF-group captured the Mayaguez, since there was no smaller boat available at the time yet.[1] Mr. Koppe asked whether this was correct. He replied that he might have forgotten this when he was interviewed. The PCF-boats were too slow. Mr. Koppe asked that whether it was correct that he did not always mean his own unit when he referred to “we”. The witness did not understand the question. Judge Fenz interjected and asked who he referred to when saying “we.” He replied that he was not referring to any specific division or unit but the general meaning. “We” were the subordinates at the front of Democratic Kampuchea.

Mr. Koppe read out an excerpt of his statement in which he had talked about the capture of the Mayaguez and had stated that he was not involved in the capture itself. He had also said that the arrest was carried out illegally, since the boat was in international water.[2] The witness confirmed the statement that he had given to DC-Cam. His unit was tasked with guarding the ship after it was captured. The crew members of the Mayaguez were arrested and sent to Kampong Som. At 10 pm, they were told to leave the Mayaguez, since the American troops were coming to attack them. The next day, the aircrafts or helicopters landed and there was fighting. There were two of them. When they were about to land, “we fired at them”. One aircraft or helicopter was shot and fell to the ground. After the incident, there “was intensive bombing on the island.” The fighting ships were firing to their island. When Mr. Koppe asked who shot down one or two of the aircrafts or helicopters, Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang interjected and queried whether the questions about the Mayaguez-incident were within the scope of the trial. Mr. Koppe responded that the reason why he inquired about this incident was of general interest, but also to establish the position of the witness. After the bench conferred for a few minutes, Judge Fenz asked whether establishing the credibility of the witness was the only reason.

Mr. Koppe referred to Elizabeth Becker’s book in which she had said that the Thai embassy had stated that he local authorities often acted autonomously.[3] Mr. Koppe explained that the Mayaguez incident and the other two incidents should be seen in this light. Mr. Koppe was allowed to proceed.

The witness said that he himself shot down a helicopter. He was severely wounded and used his 12.7 gun to shoot the helicopter. “Of course, that helicopter was shot down.” The orders, during the fighting on a battlefield, focused on eliminating the enemy. “We were autonomous and we had to defeat our enemy.” When being asked what he meant that he was autonomous, he replied that they were “self-mastery” and that they had to defeat the enemy. The order for the capture of the Mayaguez came from the division to the regiment and then down to the battalion and to the soldiers on the ground. The order came from the upper echelon.

When Mr. Koppe asked how the witness knew that the orders came from the upper echelon, Mr. Koumjian stood up, but sat down when Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne said that Mr. Koppe should rather rephrase the question, since the witness had said that he had been detached of the artillery division at the time. Mr. Koppe said that he thought the navy did not exist at the time yet and that he was probably still a member of the artillery division. He asked the witness nevertheless whether he was reassigned to another unit. The witness replied that he was part of the infantry unit when the attack occurred. Mr. Koppe repeated his earlier question and asked how the witness knew that the order came from the upper echelon. He replied that he knew cadres within the battalion-, regiment-, and division levels. Thus, he knew that the orders came from the upper echelon. Division 164 had seven regiments. He knew cadres within those seven regiments. For example, Ta Nhan was within Regiment 61.

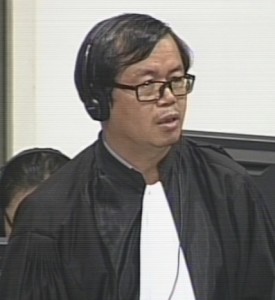

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break. After the break, Mr. Koppe asked who gave the order to whom to arrest the Mayaguez. The order came from Ta Muth, who was in charge of the division. He gave the order to members of the navy to arrest the ship. When the order came down to the battalion, the battalion would pass the order on to the soldiers. The navy soldiers would not have dared to seize and capture of the vessels if the order had not been from above. “No one wanted war again.” Mr. Koppe asked whether it was not in fact true that he had “no idea” who gave the orders to stop the Mayaguez and that he simply assumed so. He could make “the objective conclusion” that there must have been orders from above. After the witness did not shed more light on this matter, Mr. Koppe moved on.

Chain of command

Mr. Koppe asked whether witness knew how many members – combatants and non-combatants – there were in division 164 in approximately October 1976. The witness did not know the exact number of combatants. Mr. Koppe then asked how many combatants and non-combatants there were in his regiment. The witness replied that there were four battalions within his regiment. They were guards on the island. Regiment 62, according to the witness, were those who were combatants stationed on the island. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was accurate that there were around 1060 combatants in his regiment. The witness replied that one regiment consisted of 400 members.

Judge Fenz asked for references, which Mr. Koppe gave.[4] Mr. Koppe asked whether he knew all the soldiers in his division. He replied that he only knew some senior cadres when being part of Regiment 62. He only knew commanders of battalions and regiments. He did not know all members of regiments. He received orders from the upper echelon, the upper echelon being the battalion.

He received instructions from the battalion, and “perhaps battalion may have received instructions” from the level above. He could not recall the names of members of the battalion who killed the Vietnamese couple, an incident he had described last month as well. “I was part of a battalion and we were under different regiments. At the time, I was stationed close to the place. Most of them may have died already.” He remembered Yeang and Han, the latter having been head of the so-called Special Unit. He did not remember the names of specific commanders. Mr. Koppe pressed on and asked who was giving whom an order. Yeang gave orders to soldiers. Whenever soldiers were asked to perform a specific task, they would be called into a meeting. The order came through the telegram and went through the chain of command. That task was performed immediately after receiving the order. He was in no position to read the telegram. At the part, he was part of Company 53. The office of the battalion was about 500 meters away from Company 53. Thus, their offices were close to each other. The Vietnamese recaptured Koh Poulo Wai in 1975. Soldiers in one battalion were captured by the Vietnamese troops and transferred to another island. Mr. Koppe asked whether the incident he had described had not been in 1976. He replied that he was hospitalized by that time in Koh Tang in late 1976, when the Vietnamese captured the island.

Mr. Koppe sought more clarity: There had been one incident where a Vietnamese couple had been executed together with their baby on Koh Poulo Wai Island. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that it took place on this island, which the witness confirmed. Mr. Koppe then asked whether he had said that the Vietnamese had captured the island in 1976, which the witness also confirmed. The witness clarified that the Vietnamese had not captured the island yet when the couple was arrested. He was assigned to that island after the Vietnamese had been withdrawn from the island. The killing of the Vietnamese family took place when he was reassigned to the island with his unit.

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian

Mr. Koppe then referred to another extract from Elizabeth Becker’s book, which seemed to indicate that the local leaders had a poor sense of geography.[5] Mr. Koppe asked whether this was correct. The witness replied that he could not answer this question. Mr. Koppe then inquired whether the re-capturing of the island took place in 1975. Mr. Koumjian said that to his understanding, the Vietnamese had captured and evacuated the island in 1975. The witness replied that the Vietnamese returned the island to Cambodia after three months.

Mr. Koppe asked the Chamber whether it was possible to give the floor to the Khieu Samphan team first and that he would take over if there was time left. The President granted this request.

National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn took the floor and asked whether he was correct in summarizing that the witness had been wounded on Tang Island, that there was separate fighting on Poulo Wai Island subsequently and that three months later after the fighting with the Vietnamese, the Vietnamese returned the island to the Cambodian authorities, which the witness confirmed. The President reminded him to refrain from doing so and only addressing the witness with his pseudonym. Mr. Sam Onn then inquired who the superior commander was when being stationed Koh Poulo Wai Island. The witness replied that it was Ta Yeang first and then Ta Samnang. After the fighting with the American and Vietnamese troops in 1975, he was assigned to be stationed at that island, where he stayed until 1977. Then, he was assigned to be part of the navy. In mid-1977 – in April or May – he was assigned to the navy.

In 1975, he tried to refashion himself after they had not trusted him on Poulo Wai Island. Later, he gained the trust and was reassigned to the navy. Mr. Sam Onn requested to present a document to the witness, which was granted.[6] Mr. Sam Onn inquired whether he knew the highlighted name on the document. He said that he did not know the names of the people on the document. Mr. Sam Onn read question and answer 10 from this document, in which the interviewed person had said that he was part of Battalion 450, which was also called the Special Unit. Mr. Sam Onn asked whether the witness was part of the group that was sent from Kampong Som.

Mr. Koumjian interjected and said that he had heard the witness say that the Vietnamese retreated from the island and not that the Khmer Rouge recaptured the island. The witness confirmed that the Vietnamese leave the island. He did not leave Kampong Som to go to the island. He was stationed there later. The soldiers who were captured by the Vietnamese were returned.

Mr. Sam Onn asked to clarify whether the Vietnamese stayed on the island for three months or whether they had left the island and three months later the Khmer Rouge were stationed there. The witness replied that his unit went there immediately after the Vietnamese withdrew. He did not see any Vietnamese upon his arrival.

Mr. Sam Onn then asked whether there were instructions to arrest Vietnamese soldiers and civilians if they entered the territorial waters. The witness replied that their duty was to arrest anyone who trespassed the border. Mr. Sam Onn then requested leave to present a document to the witness, which was granted.[7] The witness told the court that he made the report before being assigned to go to Tang Island. There was no fighting incident on Koh Ou Chheu Teal Island. It took them around three to five hours to reach the island.

At this point, International Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud interjected and stated that the document Mr. Sam Onn had referred to a document that was subject to a request that had to be discussed tomorrow. The President announced that they had issued an oral ruling this morning. The President then adjourned then hearing or a break.

Fighting on the islands

After the lunch break, Mr. Sam Onn resumed his line of questioning. He returned to the fighting between Vietnamese troops and the Khmer Rouge on Poulo Wai Island. He asked whether the combatants were instructed to “make troubles” with the Vietnamese troops. The witness replied that they were not instructed to attack the Vietnamese troops, but that they were to defend the Cambodian territory.

Mr. Sam Onn then inquired whether he was instructed to capture Vietnamese ships as well. The witness replied that when the Vietnamese fishing boats entered the territorial waters of Cambodia, they did not have weapons. He noticed that some fishing boats had one or two M-16 weapons. He learned this through the “task that we had performed.” When the Thai or Vietnamese fisher boats entered the maritime territory of Cambodia, they had to capture the boat. If they were armed, they had to attack the boats.

Mr. Sam Onn then referred to one of the witness’s statements and asked for a reaction to the excerpt he had read: According to the other witness, when seeing that warship entered the territory, they had to make reports to the division so that they could intervene. “As a commander of the island” the cited witness was responsible for making decisions to counter small boats. This witness had testified that sometimes more than ten Vietnamese motorboats entered their territorial waters.[8] Today’s witness confirmed that he was aware of what had been read out. However, they were responsible for a different task and never encountered such an incident. The other regiment used to encounter such incidents, but they were in different regiments.

National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn

Mr. Sam Onn then referred to the witness’s testimony of December 16 2015 during which he had said that he saw such an incident once or twice and that people were taken to Kampong Som.[9]

Mr. Sam Onn further referred to one of the witness’s statements, during which he had said that there were thousands of people arrested and people being sent through Ou Chheu Teal four or five times per month.[10] The witness replied that he saw the arrests as he had mentioned earlier. “I did not tell lies to the court. This actually happened at the time and Vietnamese people were sent to Ou Chheu Teal Port” before being sent elsewhere. Arrests occurred every month and there was intense arrest throughout the year. Mr. Sam Onn said that his testimonies contradicted each other: one statement said that there were two or three arrests a month, while the other statement indicated that thousands of people were arrested four or five times a month. The witness replied that there were two incidents of Vietnamese arrests where they were sent through Ou Chheu Teal being sent elsewhere.

He got injured during the fighting on the island. He was hospitalized for a month before being reassigned to work in his unit. He arrived in May or April 1977 in Ou Chheu Teal Port, but he was not exactly sure about the year and the month. He was trained there for one month. The following month he was sent to study technical skills at Rong Island. Upon his arrival at the island he went to Damnak Sdei, and was also stationed at Sokha Hotel.

Mr. Sam Onn referred to the witness’s testimony of December 16 2015[11] and asked whether the Vietnamese were sent to Ou Chheu Teal Port when he was stationed there for training. The witness replied that he was part of the messengers’ unit at the time. He worked in this messengers unit until the entry in 1979. The witness confirmed that he witnessed the transfer of arrested Vietnamese frequently. In 1978, he no longer saw the transfer of Vietnamese people.

A witness had testified about the training of soldiers and that ordinary ships were not allowed to anchor at Ream Port. Mr. Sam Onn wanted to know his reaction.[12] The witness replied that Vietnamese and Thai people were sent to Ream Port, as they were also sent to Ou Chheu Teal Port. Torture occurred at both ports.

When Mr. Sam Onn repeated his question, Mr. Koumjian interjected and stated that there might have been a translation issue, since the version he had stated the opposite of what had been said in the English version. The witness replied that he did not object to the account that Ream Port was an international port. There were no Chinese people at this port.

Mr. Sam Onn then inquired whether the witness received an order to kill a few Vietnamese people as indicated in his Written Record of Interview. He replied that he did not dare to violate rules or regulations as a combatant, unless they received an order from above. The order came from the upper echelon, after which the soldiers had to “kill a few people right away.” Bau Samnang was one of the commanders of the battalion. His unit carried out the orders, but he himself did not kill them. When arresting them, they had to kill them immediately. He has never seen Samnang since 1977 and was unable to tell the court whether he was still alive or not. There was an instruction to execute people when the number of arrestees was small. The orders were conveyed through meetings that took place at the battalion level or regimental level. Mr. Sam Onn asked for clarification about the meetings: were these held per group or per entire battalion? The witness said that he never attended meetings at the regimental level. Neither did he ever attend any meetings held at the divisional level.

The Vietnamese as the hereditary enemy

Mr. Sam Onn then inquired how he learned that the Vietnamese were the “hereditary enemy”. The witness replied that he learned this during a study session on Poulo Wai Island.

Mr. Sam Onn inquired whether Pou Ty Wai and Poulo Wai Island were the same, since he had mentioned these two in the statement. The witness replied that he referred to one island. Sometimes this island was called Poulo Wai Island, sometimes Pou Wai Island, and sometimes the new or old island. During this time there were clashes with the Vietnamese troops on land but not on the island. His battalion commander Samnang gave the information to them. He was on Poulo Wai Island until April or May 1977. At this point, he was reassigned to the marine. The study session took place in early 1977. Samnang was a commander of a battalion. The witness did not attend any study session at any higher level than the battalion level.

Mr. Sam Onn then referred to the conflict with the American troops that he had talked about this morning. Mr. Sam Onn referred to one of the witness’s statements, in which he had said that they had been attacked by a warplane.[13] He replied that the ship had departed. After the departure of the ship, the island was attacked by a warplane until 7 pm. After this attack, the Americans fully withdrew from the Cambodian territory both in the water and in the aerial space.

He did not attend any other study sessions later, since there were none.

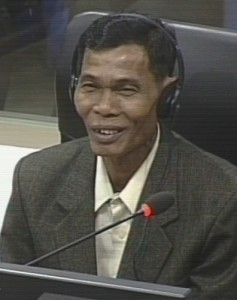

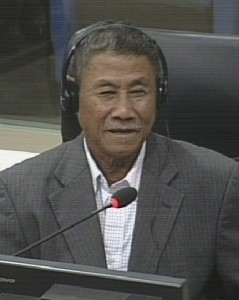

Witness 2-TCW-1000

After the announcement of the Communist Party of Democratic Kampuchea, which was announced after the war ended in 1975 according to the witness, he learned the names of the leadership. These names included Khieu Samphan. He had heard Khieu Samphan’s name before the war ended, but heard of Pol Pot afterwards. Meas Muth was the commander who was in charge of the division in Kampong Som. He heard about this in 1975. He could not remember who the military commander in chief was or who in charge of politics was. Mr. Sam Onn asked whether the name Son Sen rang a bell. The witness replied that he had heard of the name but never saw him and had also not received information whether he was the military commander in chief.

When Mr. Sam Onn referred to another person’s statement, the witness replied that he never heard instructions not to arrest Vietnamese people – he had only heard instructions to arrest them.[14]

With this, Mr. Sam Onn finished his line of questioning and the floor was given again to Mr. Koppe.

Mr. Koppe asked whether Samnang was always his commander when being stationed at Poulo Wai. He replied that he was his commander. There were two battalions under his the regiment. Samnang did not join him in the fighting. A member under Samnang, called Bong Nik, participated in the fighting. He confirmed that Bong Samnang was always his direct supervisor.

Mr. Koppe asked whether the incident where the baby had been thrown into the sea took place between the two islands. The witness replied that he was sent to work near a port when he saw the baby being thrown into the sea. It was thrown from a boat by forces from Poulo Wai. Mr. Koppe asked whether the two incidents that the witness had described took place under the supervision of Bong Samnang. He replied that he did not know whether his immediate superior respected the higher cadres. He said that Bong Samnang was the commander of the division and it was therefore his decision.

Mr. Koppe read out an excerpt of another soldier of Division 164.[15] This witness had said that they were instructed not to arrest civilians. They could arrest civilians and interrogate them whether they were really refugees. Mr. Koppe said that this seemed to be in contradiction with the orders by Samnang to kill civilians immediately. The witness said that he did not know how to respond. He reiterated that there was no release after their arrests. Their confessions would be broadcasted over the radio. He did not know about other regiments. The witness explained that he was one of the combatants of division 164 and also under regiment 62. They were not “bandits” as put forward by Mr. Koppe. From 1972 until 1975 and until the dismantling of the Khmer Rouge, they were fighting. He had used this term himself, because there was war during the time. They had to capture the boat regardless of whether it belonged to Thailand or America. He had referred to the soldiers as wild bandits, since they were not aware of any international or maritime law.

The President reminded Mr. Koppe that his time had ran out. Answering Mr. Koppe’s last question, the witness said that Regiment 62 was responsible for the capture of the Vietnamese. Several battalions were involved. With this, Mr. Koppe concluded his cross examination. The President thanked the witness and dismissed him. The hearing of submissions and responses regarding the request that was mentioned this morning would be heard tomorrow morning at the beginning of the hearing.

A new witness: Theng Phal

After the break, the testimony of 2-TCW-848 began. New witness Theng Phal – who was first known as Theng Huy – was born on November 11 1950 in Pou Chhandan Village and now works now in Village 7 in Preah Vihear Province.

National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Seng Leang

The floor was then granted to National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Seng Leang. He opened his questioning by asking where Mr. Phal lived before 1975. He replied that he lived in Pou Chhandan Village in Preah Vihear Province. The Khmer Rouge took control in 1975. This was at small scale, though and there were many Vietnamese troops in the area. The Khmer Rouge troops were less than the Vietnamese troops.

Another villager had said that the Khmer Rouge had said that the Khmer Rouge took power in Pou Chhandan Village in 1972 or 1973.[16] The witness confirmed that this was correct. He did not have any particular position at the time and was accused of being the son of a capitalist. The village chief maintained his position when the Khmer Rouge took power. By 1975, the village chief was replaced by two people from outside: Seng and Huon. Huon was the village chief, while Seng was his deputy. He did not know about the presence of militiamen. Mr. Phal went to school together with Ieng Ung, who he had mentioned before, and he had been friends. Back then, Ieng Ung was an ordinary citizen digging the canals and working the fields. Mr. Leang then wanted to know whether the witness knew someone called Eng, which Mr. Phal denied.

Ung had said that he had been a militiaman for two months.[17] The witness replaced that Eng was a militiaman in the village. He could not give more details. Mr. Leang then wanted to know whether he knew someone called Dry or Try. The witness replied that this person had been quite old already back then and has passed away by now.

Ieng Ung had said that Ta Try had been the owner of a horse cart.[18] Mr. Phal replied that he knew that Ta Try had been driving a horse cart but did not know his position. Muth was the village chief and there was another person called Chaem. Muth was part of the Zone committee, as was Chaem. He knew someone called Moeun. This person was a group chief at the time. He was in charge of transplanting rice plants. Noy was the militia chief and also the security chief.

The witness himself was “simply an ordinary citizen” after 1975. He was forced to work. There were only three families with married Vietnamese couples. He did not know the specific number of Vietnamese people living in his village.

Assistant Prosecutor Andrew Boyle

Witness Theng Phal

International Assistant Prosecutor Andrew Boyle took the floor. He asked whether the witness knew whether the Vietnamese advisors and soldiers had left the village by the time that Seng and Huon had been appointed chief and deputy chief of the village. Mr. Phal replied that the Vietnamese had already left the area. Mr. Boyle then asked whether he knew the three Vietnamese couples that lived in his village. Mr. Phal replied that Lak My had a Vietnamese wife; Oeun had a Vietnamese husband named Chhuy; Nhang was the husband of Tek. Mr. Boyle inquired whether the name Sum San reminded him of being the wife of Lak My, which the witness could not answer.

Mr. Boyle requested permission to show the first page of another 2-TCCP-869’s statement to ascertain someone’s identity.[19] The request was granted. However, the witness did not recognize the name. Mr. Boyle requested to present the first page of another document, which was also granted.[20] The witness did not recognize this name either. Mr. Boyle stated that the witness had identified each of these names that he presented to him.[21]

Regarding the three Vietnamese couples, there was an individual called Noy and his wife Tek, Ta Chhuy and his wife Oeun, and Lak Ny with the Vietnamese wife whose name he could not remember. Ny was a Cambodian citizen who married a Vietnamese wife. Oeun married a Vietnamese husband after 1975. The three couples were living in Pou Chhandan village. The husband of the female Tek came to conduct business in the country, after which they got married, which also happened to Chhuy. Ny was an ordinary citizen and married a Vietnamese woman who was a waitress in a restaurant. He could tell that they were Vietnamese, because they spoke Khmer with an accent. “Later on, they fell in love with the man or the woman and they got married.” At this point, the President adjourned the hearing and announced that the hearing would continue tomorrow with 2-TCW-904 being on the reserve, who would testify on the treatment of the Cham people.

[1] E3/9092, at 00978569 (EN), 00955497 (KH), no French available. [2] E3/9092, ibid. [3] E3/20, at 00237902 (EN), 00638463 (FR), 00232262 (KH). [4] E319/23.3.45.1. [5] E3/20, Elizabeth Becker, at 00237902-03 (EN), 00232263 (KH), 00638464 (FR) (This equals page 198). [6] E319/23.3.12. [7] E319/23.3.21. [8] E319/23.3.21, answer 21. [9] At around 10:39:04. [10] E319/23.3.46, at question and answer 10.

[11] At around 10:55. [12] E319/23.3.66, at Question and Answer 66. [13] E3/9092, at 00955499 (KH), 00980438 (FR), 00978570 (EN). [14] E319/23.3.12, at answer 25. [15] E3/9113, at 00974222 (EN), 00926399 (KH), no French. [16] E§/9352, at 00231661 (EN), 00226264 (FR), 00225361 (KH) [17] E3/9352, at 00225356 (KH), 00231661 (EN), 00226264 (FR). [18] E3/9352, at 00225653 (KH). [19] E3/7562, DC-Cam Statement of 2-TCCP-869. [20] E3/7594, DC-Cam Statement of 2-TCW-957. [21] E3/5244, at 00233299 (EN), 00224794 (KH), 00231948 (FR).

Featured Image: First Trial Chamber hearing in Case 002/02 for 2016, 05 January 2016 (Courtesy by ECCC Flickr)