Back to the Cham Segment

Today’s session in front of the ECCC was divided into three parts: First, there were procedural discussions about calling additional witnesses and about the potential testimonies of two Civil Parties. The Khieu Samphan team objected to calling new witnesses, arguing that this would infringe the rights of the accused. Second, Theng Phal concluded his testimony. He provided further details on the arrest and execution of three Vietnamese people and their children. Third, ethnic Cham Sos Rumly commenced his testimony. He gave evidence with regards to the administrative structure in the area and his tasks.

Oral submissions regarding additional witnesses

At the beginning of the session, the Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn announced that submissions regarding requests to admit new documents and call new witnesses in relation to the Vietnamese segment would be heard.[1] Second, the Civil Party Lead-Co Lawyers would give an update on Civil Parties 2-TCCP-884 and 2-TCCP-849. Third, the witness Theng Phal would be heard. Fourth, 2-TCW-904 was on the reserve and might give testimony. The Trial Chamber Greffier then confirmed the presence of all parties with the exception of Khieu Samphan defender Anta Guissé and standby-counsel Calvin Saunders.

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

The parties were then invited to make submissions regarding the requests by the Nuon Chea Defense Team. Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde stated that the Co-Prosecution did not have any objection as far the request by the Nuon Chea team to call witnesses TCW-428 and 2-TCW-823. As for the last witness 2-TCW-1010, Mr. de Wilde said that the Co-Prosecutors supported the request, since this person – who related to the Vietnamese segment – established, in his view, the link between the crimes committed in Kampong Som and S-21.

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud stated that the Civil Party lawyers would rely on the chamber’s wisdom for deciding the matter. National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn requested leave to make a joint submission for both requests later, which was granted.

Turning to the next request, namely the Co-Prosecutor’s request to call additional witnesses, it was said that 2-TCCP-245 was in good health and ready to testify now.[2] The Nuon Chea Defense Team did not have any observations regarding the request.

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn objected to the requests to hear additional witnesses. He argued that it violated the rights of the accused in several ways. For one, the Co-Prosecutors had already requested to hear several witnesses twice – the request was therefore repetitive and delayed the proceedings. As for the new witnesses that had not been requested earlier, he argued that the Co-Prosecutors should have filed the request earlier. He reasoned that this failed to provide the defense team with adequate time and facilities to prepare the defense. According to Mr. Sam Onn, there had been already sufficient witnesses relating to the regions in question and the Prosecution was now simply trying to fill a lacuna for an investigation that should have been done earlier and for witnesses that should have been requested earlier. He seemed to further argue that if the Judges granted this request, they would side themselves with the Co-Prosecution. Moreover, he submitted that granting the request would actually signify the commencement of the trial against Meas Muth – a case that was still under investigation and that the Defense Teams were not part of. He compared the granting of this request as a “can of worms” that would infringe the accused’s rights, since it would introduce case 003 into Case 002. When Mr. Sam Onn finished his submission, Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe stated that he concurred “literally with every word that the Khieu Samphan team has just said” and had simply not made a submission himself, since they had “given up” on doing so.

Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde

Mr. de Wilde took the floor and responded to the last remark from Mr. Koppe by pointing out that Nuon Chea had also requested additional witnesses and experts to be on the Trial Chamber list of witnesses. As for the argument that the request came in late, Mr. de Wilde put forward that they had waited “for the best moment”, that is to say during the break from the hearing – as they had already argued in their submission, he said. Relating to the renewed request to call witnesses, Mr. de Wilde clarified that the Chamber had not rejected the witnesses before, but simply had not selected them. Furthermore, since the burden of proof lay with the prosecution, it was understandable that they called for additional witnesses. This served not to delay the proceedings – an accusation that he called “unfair, since both Defense Teams had repeatedly walked out of proceedings – but to establish sufficient facts. Since there were almost no Vietnamese survivors, this was important. He also acknowledged that witnesses turned out not to confirm the stories that were thought they would confirm sometimes. This had to be taken into account. As for the “can of worms”, he said that this term was “not very honest”, since the documents had been forwarded to the parties in due course (they had been disclosed on May 18 2015) and therefore became part of the Case 002 documents – they were not Case 003 documents anymore.

Civil Parties 2-TCCP-869 and 2-TCCP-844: willing to testify

Judge Claudia Fenz

Next, observations relating to Civil Parties 2-TCCP-869 and 2-TCCP-844 were made. National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang stated that they had met on December 28 2015 and January 4 2015 with the two Civil Parties. The Civil Party 2-TCCP-869 had indicated that she was scared to testify in front of the “crowd of the court”. After the two meetings, the Lead Co-Lawyers were of the view that if she was to testify, she should do so only in the morning session. This would give her time to concentrate and respond to the questions and not put pressure on her health conditions. The questions should be simplified. Under these conditions, the Civil Party would be willing to testify.

As for the second Civil Party – 2-TCCP-844 – this Civil Party had confirmed that his health party was better than the information provided by WESU. He requested the Trial Chamber to appoint a doctor to examine Civil Party 2-TCCP-869 and 2-TCCP-844. This prompted Judge Claudia Fenz to ask why a new expert should be appointed. Mr. Ang replied that the Civil Party should be examined before testifying. Marie Guiraud clarified that they would rely on the wisdom and discretion of the chamber for the medical expertise and that someone should be present to be able to deal with possible emergencies.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

The Fate of Ngang

After the break, the floor was granted to Assistant Prosecutor Andrew Boyle to resume his line of questioning. He asked whether Mr. Phal was ever aware about steps to identify those people in his village who were of Vietnamese ethnicity. The witness replied that he had not paid attention to this. He was neither aware of Khmer Rouge cadres going to villagers asking them questions.

Mr. Boyle referred to the DC-Cam statement of 2-TCCP-869, who had testified that they collected statistics about the Vietnamese people; she had told them that her husband was Vietnamese.[3] The witness replied that he was not aware of these practices.

Mr. Boyle then asked when the last time was that Mr. Phal saw Mr. Ngang[4], a person he had mentioned yesterday. He replied that this person cut rumpea plants with him. He got married in the village. They were assigned to cut the plants together in late 1976 or 1977 for a period of one month. In the end, they only went there for six days before they “were taken back” by Angkar. The deputy chief took them back. Upon their arrival, they saw Seng who told them that they had to go back to the village. Ten of them, including the witness, were sent back. “Among them, there was Ngang.” When they returned, they were walking while Seng was on a bicycle. Midway, the chain of the bicycle broke. The witness had offered to help repairing the bike. Ngang was requested to repair the chain. While they were moving, they were thinking of Ngang and other members of the group. Ngang stepped on a spike and got injured. They were told to stop at Au Kandal Village with Wat Chas close to it. It was used as a Security Center. It was located far away from the village on an open field. He could not see Wat Chas from where they were, since it was blocked from a forest and the village. Asked about armed Khmer Rouge in the vicinity of where they said, Mr. Phal recalled that “everyone was armed in that location”. He witnessed the armed people himself.

International Assistant Prosecutor Andrew Boyle

During the journey to Po Chendam village, they stopped briefly. When returning to the village, Ngang had not arrived yet. He had heard that Chuy, the husband of Oeun, had been put on a horse cart. Thus, he was afraid that Ngang was killed there. The husband was Vietnamese. Ny had a Vietnamese wife, but she looked Khmer. From the day that they went to cut the plants, Ngang disappeared. The next morning after arriving at the village, he saw Seng. There was a rumor that Vietnamese people were gathered together and executed. The wife of Ngang remained in the village and was not taken anywhere.

At this point, Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer interjected and asked Mr. Boyle to clarify which person the witness was referring to: was it Ngang or Ngoy? Mr. Boyle replied that he had understood it in a way that Ngang could be pronounced both like Ngang and Ngoy. When he asked the witness, however, Mr. Phal clarified that Ngoy was the son and Ngang the father.

To clarify further, Mr. Boyle asked whether it was correct that the person he went to cut the rumpeak plants with was the father Ngang, which the witness confirmed. Ngang’s wife was Khmer. She lived in Po Chendamvillage for a long time.

Mr. Boyle then inquired whether the children were taken away during the period of Democratic Kampuchea. The witness replied that they remained living in the same house.

Lach Ny’s Wife

Mr. Boyle further wanted to know more about the wife of Lach Ny. He asked how he learned that his wife had been taken away. Mr. Phal replied that “that was the plan of Angkar”. They said that she was taken away for re-education. He replied that when he returned from cutting the plants, he heard villagers talking about the wife of Lach Ny and another one. Both were taken away for re-education. They had two or three children and all children were taken at the same time. Mr. Boyle then asked whether he knew any of the individuals that came to arrest them, which the witness denied.

This prompted Mr. Boyle to refer to the supplementary statement of Civil Party 2-TCCP-844, who had mentioned the people who carried out the arrests.[5] The witness insisted that he was cutting vine when the wife of Lach Ny was arrested. Mr. Boyle pressed on and asked whether anyone else had mentioned the name. The witness replied that this was not the case – they only said that those people were taken away. Mr. Boyle asked whether the witness knew why Lach Ny’s wife was taken away. He replied that “they whispered that these people had been taken away for re-education”, but that they were executed instead. The witness did not know the reasons for this.

This prompted Mr. Boye to refer to the statement of Horn Han (the nephew of Lach Ny), who had said that the Vietnamese were taken away precisely because they were Vietnamese.[6] Mr. Koppe objected to the question and stated that the other witness’s statement could not refresh this witness’s statement, since it was first speculation and second, because this witness “as a matter of fact, he doesn’t know anything”. Mr. Boyle responded and said that it was merely Mr. Koppe’s assumption that this was speculation and that it was practice in the court to confront witnesses with other witnesses’ statements to refresh their memories. If the witness did not know he could say so. The objection was overruled.

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Mr. Boyle then asked whether cadres went to ask about the ethnicity of the villagers by going to their houses. The witness replied that he did not know whether the Khmer Rouge inquired about this, since his house was around half a kilometer away from his. At that time, Lach Ny did not become arrested, but he “became crazy”. He went around shouting and crying in the village, “because his wife had been taken away.” He did not know why the wife and the children were taken away. However, he heard people say that if the wife was Vietnamese, the children would be taken away as well. If the wife was Khmer and the husband Vietnamese, the children would not be taken away. He did not know the reason behind this logic.

When Mr. Boyle read out an excerpt of Civil Party 2-TCCP-844’s DC-Cam statement, Mr. Koppe objected. This Civil Party had said that the reason was that the ethnicity was passed on through the mother.[7] Mr. Koppe said that this was “double-hearsay”, since it put speculation of someone to this witness, who also did not know the reasons. Mr. Boyle responded that hearsay was a common law concept, while this was a civil party court. Under this system, hearsay impacted the weight but not the admissibility of evidence. The objection was overruled and Mr. Boyle repeated his question. The witness replied that he did not know how to respond to this question “because my knowledge is limited.” It was his understanding that the child was also Vietnamese when the mother was Vietnamese. He did not see those people who were taken away again. He did not know anything about a meeting that was convened before Lach Ny’s wife and her child were taken away.

Mr. Boyle referred to the supplementary submission of Civil Party 2-TCCP-884, who had mentioned a meeting in which the role of the Vietnamese was discussed.[8] Mr. Phal replied that he did not know anything about a meeting. At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Tep Chuy

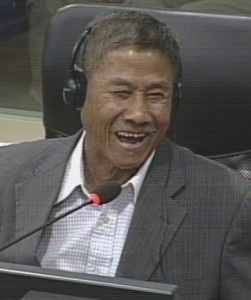

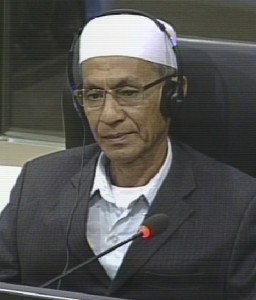

Witness Theng Phal

After the break, Mr. Boyle took up his line of questioning again. He moved on to the third individual who was of Vietnamese descent, namely Tep Chuy. The witness replied that this person had “been sent out.” He did not know the reason why he had been sent out, nor did he know where he had been sent to. He did not know the names of those who sent him away. “When I got home, the village was so quiet.”

Mr. Boyle read out an excerpt of a DC-cam statement from Civil Party 2-TCCP-869, who had put forward to the interviewers that the members of the commune had carried out the arrests.[9]

The witness insisted that he did not know how and when this person had been arrested. He heard that the Vietnamese were taken away to a study session, and Chuy was among the study session, but he did not know more. Mr. Phal has never seen Chuy again since then. His wife and his children were at home and not taken away.

Mr. Boyle asked whether it was correct that there were no longer any people of Vietnamese ethnicity once Ngang, Tek Chuy and the wife of Lach Ny had been taken away. The witness replied that there were no other Vietnamese living in that village. He never heard anyone making any announcement about Vietnamese.

Mr. Boyle then referred to the statement of the witness 2-TCW-843, the first cousin of the wife of one of the individuals he had mentioned, who had said that all Vietnamese had to be rounded up.[10] Mr. Phal replied that he never heard about the gathering of Yuon before the arrest of Ngang. “Before this, perhaps, it was a secret”. He never attended any meetings. He never saw any senior Khmer Rouge cadres.

Mr. Boyle inquired whether he had ever heard about Veal Touch, which the witness did: it was close to the place where he cut rumpeak vine. In relation to the district security office Wat Au Kandal, Mr. Boyle wanted to know whether it was connected to Veal Touch. The witness denied this.

As for Veal Touch village, it was located around one kilometer away from Wat Chas. There might have been a rumor that it was a killing place. Au Kandal was located in an open field. Mr. Boyle asked whether Veal Touch was used as a killing site. The witness replied that people had mentioned this. “It was said that people were taken away” and brought to Veal Touch.

National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang

The floor was then granted to National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang. He inquired about Ngoy, the son of Ngang: was this person the same as the individual who was the chief of the militiamen? He replied that Ngoy was a militiaman within Svay Antor commune. There was another Ngoy.

Mr. Ang then inquired whether he knew someone called Ie Poeu, which the witness denied. The three Vietnamese individuals were tasked with the same work as other people. They were transplanting rice.

The people disappeared between late 1976 and early 1977.

Mr. Ang then inquired whether there were monks between April 1975 and April 1979, which the witness denied. After 1973, there were no monks anymore. He himself had been a monk beforehand, but left monkhood in 1973. The Khmer Rouge went to reside there when there were no more monks. Mr. Ang then inquired whether there were any Buddhist ceremonies allowed in his commune between 1975 and 1979, which the witness denied as well.

As for Lach Ny, Mr. Ang asked whether it was correct that he had mental problems after his wife was taken away. The witness replied that Lach Ny became “mentally unstable”, lasting about a fortnight. “With the assistance of the villagers, he became better.” Lach Ny remarried later under the Khmer Rouge. There were no other couples in his marriage from what Mr. Phal heard.

Sao Phim’s alleged influence

The floor was then granted to the Nuon Chea team. Mr. Koppe asked about the timing of the disappearance of the people and queried whether the witness was sure that it took place in late 1976 or early 1977. The witness replied that he recalled it clearly. Mr. Koppe further inquired about “the Sao Phim event” that the witness had mentioned in his interview with the investigators. Mr. Phal replied that the Sao Phim event was the time that he also referred to the arrest and execution of the Vietnamese people. When Mr. Koppe repeated his question, Mr. Phal insisted that he referred to the rounding up of villagers. Mr. Koppe pressed on; the witness said that Sao Phim was still in charge at the time.

Mr. Koppe referred to another witness, who had referred to something called “Sao Phim’s network.”[11] The witness did not know what Sao Phim’s network was. Mr. Koppe asked whether he never heard any villagers say that these three people were involved with Sao Phim’s network, which the witness confirmed not having heard.

Mr. Koppe then asked whether Mr. Phal knew in which Sector in the East Zone the witness’s commune was. He replied that he was not very familiar with the administrative structure.

The witness confirmed having heard people referring to Sector 20. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that the witness did not know whether his district was located in Sector 20, which the witness confirmed. He did not know which villages or communes belonged to that Sector. Mr. Koppe then asked whether he had ever heard of Chea Sin alias Sun, which the witness denied.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether Mr. Phal had heard of the chief of the district called Lyng, also known as Kroh Lyng Kroh Long. The witness replied that the district chief was known as Ta Chankuon Prambay. He had been replaced later. Mr. Koppe asked whether Ta Chankuon was also known as Ta Run. He had not heard of this alias.

Mr. Koppe then asked whether he had ever heard the “sounds of warfare” or armed conflict. Mr. Phal said that he had heard that there was shelling in the Cambodian territory. He was told that Vietnamese were shelling into the Cambodian territory, but did not pay much attention to that.

Mr. Koppe then inquired whether Mr. Phal had ever heard that Tek Chuy was a former Vietnamese soldier, which the witness denied. He said that he had been a Vietnamese merchant. Mr. Koppe asked whether he had ever heard an announcement on the radio that people were targeted because they were Vietnamese, or whether he had heard this from people who heard it on the radio. The witness said that he never heard of such a radio announcement. The broadcast consisted of revolutionary broadcasts.

National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn

Mr. Koppe asked whether he was able to say what the reason was for the rumor that Vietnamese people were arrested because they were Vietnamese. The witness said that this started after the arrests of the Vietnamese people. Mr. Koppe then inquired about monkhood. The witness said that the chief monk left monkhood in 1973. He gave the chief monk a massage when he felt pain in the leg, and this is how he got the information.

National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn took the floor. He inquired when the witness knew the three Vietnamese people. He replied that he first knew Ngang and later knew Ny’s wife. Dyn Oeun and Chuy, he knew them later after the war. Oeun got married. He could not remember the exact years.

Mr. Sam Onn proceeded to cite another statement: a witness had said that Chuy had been a former Vietnamese soldier who came to live in Po Chendam.[12].

Mr. Sam Onn asked for a reaction to this extract. The witness replied that he was living far away from Oeun and Chuy and therefore did not know. The witness worked in the same cooperative as Ngang and Ny, while Chuy used to live far away.

Another witness had said that the three individuals were former soldiers.[13] Mr. Sam Onn inquired whether this refreshed the witness’s memory. Mr. Phal replied that the statement was not true. Chuy was a “newcomer” and “I did know when Lach Ny’s wife became a soldier”, he exclaimed, since she was a woman, “how could she be recruited to be a soldier?”

Mr. Sam Onn then referred to the witness’s earlier testimony today, during which he had said that Angkar, the deputy chief, had called him back when he was cutting rumpeak vine. He asked how he was instructed to use the term Angkar: did anyone specific tell him so? The witness replied that the term Angkar meant that everyone who was in charge of any function was called Angkar. It was, in the witness’s view, widely known like that.

The President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Clarifications

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

After the break, Mr. Sam Onn resumed his line of questions. He asked how Mr. Phal knew that they asked the village chief about the Vietnamese people. He replied that they first came to ask the village chief, who knew who had just arrived in the village and who had left. He had assumed that they would assume the village authorities first.

Mr. Sam Onn then inquired about the incident when they walked back from cutting the rumpeak plants. He asked how far the place where Seng’s bicycle broke down was from where the witness and Ngang walked. There was only one road, the “dirt road” along the paddy fields. Seven or eight of them walked on the road and they did not meet anyone. He had not witnessed what happened to Ngang. He confirmed that Ngang’s wife inquired about Ngang when he returned to the village. Mr. Sam then quoted from another witness (2-TCW-957), in which a person had said that Huy (Phal’s other name) had told him that Ngang was instructed to cut wine but never came back.[14] Mr. Sam Onn asked whether he had ever told anyone that Ngang was instructed to cut the plants. The witness replied that this was not true. “No one told me that.”

Mr. Sam Onn then inquired whether Mr. Phal stood by his previous statement that the arrests were in late 1976 and early 1977, which the witness did.

Mr. Sam Onn then referred to another document. A woman said that she had been evacuated away from the village after her husband had been arrested.[15] The witness did not have any reaction towards this.

With this, the testimony of Theng Phal was concluded. The President thanked and dismissed him.

A new witness: Sos Rumly

He then ordered to usher Sos Rumly, an ethnic Cham, into the court room. He had already confirmed his background information on October 06 2015, but could not begin his testimony: the witness before him had been confronted with Rumly’s testimony and was assisted by a duty counsel. This duty counsel was the only counsel available on the day that Mr. Rumly was supposed to testify, which might have given rise to a conflict of interest.

National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Srea Rattanak

The floor was granted to the National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Srea Rattanak. He started questioning Mr. Rumly by asking where he lived between 1970 and 1975. Mr. Rumly replied that he was living in Trea II Village in Kampong Cham Province. From 1970 until 1975, he was “living under the support of his parents”. He had five siblings. There were below 1000 families living in his village back then. Mr. Rattanak asked whether the 1,000 families were living in the same village or in another village in the same commune. He replied that they were living in five villages in Trea Commune. They were around 1,000 villagers in Trea village. There were five Cham villages in the commune and three Khmer villages. There was one mosque in Trea. There were also hakims in his village. The name of one hakim in his village was Ahmad. There were three hakims in total. They were arrested and held in a security office. In other villages, the leaders were also taken away and educated. In 1970, they were still allowed to worship their religion. They were also allowed to speak their language between 1970 and 1975. In 1975, the Qur’ans were collected and taken to the hakim’s house. Later they were collected again and destroyed. They had access to mosques between 1970 and 1975. From 1975 onwards, the mosques were closed, the Qur’ans were collected and they were banned from reciting the Holy Book of Qur’an.

Witness Sos Rumny

There were meetings between village leaders and the Qur’an was considered “reactionary”. The mosque was transformed into a hospital later. The village chief appointed Mr. Rumly as a youth chief of Trea Village Number II, since he was considered a “good farmer” and he had a “good biography”. They had said that his parents had no connection with the former administration. He was in charge of about 30 youths. He was instructed by the superiors to clear the forests at the back of their houses. He was in this position until 1975. After 1975, he was transferred to a mobile unit. He was the chief of a group in this mobile unit. After three months in this mobile unit, he was assigned to be the Trea commune clerk. He was appointed as such in late 1975. Chean alias Sy was part of the commune committee. He was given documents to take charge of. It was said that he had a “good and beautiful writing” by a cadre in charge of the agriculture in the district. There was a letter to invite commune chiefs and other people to a meeting that the witness prepared. The commune chief made him write the letter. His office was within the commune office. The office was located in Trea Village II. He stayed in the same office “until the end.” When Mr. Rattanak asked to clarify, Mr. Rumly said that he worked there until 1978. Later it was transformed to be the district office. In 1978, the former commune chief had been arrested and sent to Steung Trong.

The office was dismantled because, so he had heard, that the “East Zone betrayed the regime”, after which the Southwest Zone people took power. After the rumor, there were around 30 black clad forces that came to his location. They decided to flee. They did not flee far away, but went to a location that was far away from the commune office. Mr. Sam Onn asked whether other Cham people were allowed in other positions allowed in the commune office, which the witness denied.

The hearing concluded at 4 pm and will resume on Friday, January 08 2016, at 9 am.

[1] E380 E381 E382 [2] E381 [3] E3/7562, 01170650-51 (EN), 00034056 (KH). [4] There was confusion about the names Ngang and Ngoy that was later resolved: Ngang was the father and Ngoy the son. In order not to confuse the reader, the name of the person that the witness actually referred to is used. [5] E3/5630, at 00678289 (EN), 00891890-91 (FR), 00895420 (KH). [6] E3/7571, at 00598001 (EN) 00657195 (FR), 00034474 (KH). [7] E3/5640, 00645403-04 (EN) 00657819 (FR) 00034405 (KH). [8] E3/5630, at 00678289 (EN), 00891890 (FR), 00895419-20 (KH). [9] E3/7562 2-TCCP-869, 01170694-95 (EN), 00034092 (KH). [10] E3/7559, 2-TCW-843, at 00321978 (EN), 00034290 (KH), 00854140 (FR). [11] E3/9339, at 00234115 (EN), 00232824-25 (KH), 00283171-72 (FR). [12] E3/7809, at 00271368 (KH), 00282563 (EN), 00486104 (FR). [13] E3/7559, at 00034292 (KH), 00890542 (EN), 00854142 (FR). [14] E3/7810, at 00271388 (KH), 00486112 (FR), 00282333 (EN). This corresponds to page 2 in Khmer. [15]E3/89.

Featured image: Witness Theng Phal (ECCC: Flickr).