“He told me that those Cham people would be smashed”, witness tells the Court

Former commune clerk Sos Romly concluded his testimony today, January 08 2016, in front of theint Trial Chamber of the ECCC. He gave evidence concerning the authority structure of Trea Village and Trea Commune and testified on the treatment of the Cham, their evacuation and the arrests of cadres.

Religious Practices

At the beginning of the session, Trial Chamber Greffier Em Hoy confirmed the presence of all parties with Nuon Chea following the proceedings from the holding cell. No reserve witness was scheduled.

The floor was given to International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian, who inquired what education he had before 1975. The witness replied that he had not received any education until then. Mr. Koumjian asked where he learned to read, since he had indicated to have been chosen as a clerk because of his handwriting. He replied that he went to Trea primary school until 3rd grade, “but during the time that I studied, I read a lot of newspapers.”

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian

He confirmed having practiced Islam before the Khmer Rouge took power. He confirmed being able to recall 17 April 1975. Asked whether “things started to change” for Cham people after this date, he recalled that Cham women had to cut their hair short and were prohibited to worship. Before 1975, they were allowed to practice five times a day, seven days a week, and went to the mosque on Friday. Mr. Koumjian inquired how the prohibition after April 1975 was enforced. He replied that they were told that “the religion was considered reactionary”, and they were not allowed to practice their religion privately or in mosques.

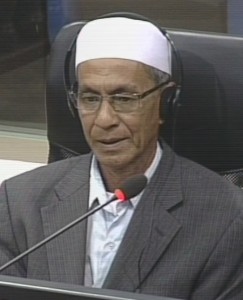

Mr. Koumjian asked whether the headgear Mr. Rumly was wearing on Wednesday and Friday was something typical for Cham people, which the witness confirmed. Mr. Koumjian then asked whether he was wearing the headgear also after April 1975. Mr. Koppe interjected and said that the area had been in the hands of the Khmer Rouge already earlier and things did not “change all of the sudden” from April 1975. Mr. Koumjian replied that the jurisdiction of the court extended to 17 April 1975. Mr. Koumjian repeated his question. The witness said that they were prohibited of wearing these headgears.

When Mr. Koumjian inquired whether some people refused to abolish their religion, the witness recounted that people were afraid. There were arrests of hakims and teachers. “For this reason, people were afraid.” He did not know what happened to those who were arrested.

Authority structure in the district

Mr. Koumjian wanted to know who the head of the commune was when Mr. Rumly first became clerk. Mr. Rumly replied that it was Chhean. Chhean had been arrested in 1977 “under the accusation that he betrayed the party.” After the arrest of Chhean, a security cadre from Krouch Chhmar district, Sim, came to replace him. Han also came to replace Chhean. In mid-1978, both Sim and Han were arrested as well. Thirty soldiers came to arrest the two individuals.” Someone called Hor was the chief of the group that arrested the two. Hor appointed Meng to replace Sim and Han. Meng was appointed to be chief in Trea.

Mr. Koumjian wanted to know what the position of Hor was. Mr. Rumly replied that Meng was the district chief of Krouch Chhmar. Asked to clarify, Mr. Rumly answered that Meng appointed Hor to be commune chief. Hor was higher than Meng, “since Hor appointed Meng to be commune chief.” Since this caused confusion, Mr. Koumjian asked again what Hor’s position was.

The witness replied that Hor came from the Central Zone. He was the Krouch Chhmar district chief and led the group of thirty people. Hor was first in charge of the fishing unit in Steung Trong region. Mr. Koumjian wanted to know how he knew that his name was Hor. He answered that one day, his father-in-law was called by Hor to help him in the fishing region. His father-in-law told him that his name was Hor. The witness had attended one meeting with Hor.

Upon Hor’s arrival, Sim was arrested, and Han as well. Ya Yorb, the member of the Krouch Chhmar committee, was also arrested. They were the first three to be arrested. One of them, Ya Yorb, was Cham. He was part of the district committee and part of the fishing unit in Krouch Chhmar. The three individuals were sent to Steung Trong. He has not seen them since.

Hor once convened the people in a meeting. One of Hor’s colleagues was also invited. They were told that they had to attend the meeting at the district office. The district office “was one use of the commune office.” However, “nothing happened in the meeting.” They were told to go to the district office “to attend a study session”, which they did. He did not know what happened to those who went to the district office, since they never returned. He has not seen them again.

Sim and Chhean were working in the commune office. Hor and his group came to work in the commune office. The old cadres who used to work in the commune office used their houses as their office.

When Mr. Koumjian asked whether people from another area arrived in his village, Mr. Rumly recounted that some people were transported on an oxcart to Trea. These people were brought into the district office. This happened “immediately after the arrival of Hor.” This took place approximately in May 1978, but he was unsure about the month. The witness confirmed that Trea is on the Mekong River. Mr. Koumjian inquired where in relation to the river the district office was. He replied that it was near the river bank. The commune office was around 20 or 30 meters away from the river bank.

Arrests

Mr. Koumjian asked whether he knew what happened to those people who were taken to the district office. He replied that he saw “the hole where around twenty or thirty pits” were. He saw this after the liberation day of January 7 [1979]. He could not see this in 1978, since the area was flooded at the time. He saw “piles of bones” in the pits. The people who arrived on oxcarts were all ethnic Cham, according to the witness. This happened “for about ten days.” From his estimate, there were around 500 to 600 people, including children and adults. He did not know whether Hor had any contact with these people.

Mr. Koumjian turned to the next topic and asked when Mr. Rumly fled Trea. He replied that he fled to nearby areas. He had heard that the East Zone had “branded us traitors”. Since they were afraid, they fled.

He fled alone, but other cadres also fled. He fled to the forest. He was the only Cham who fled. Mr. Koumjian then inquired: “Sir, were you part of a conspiracy against Pol Pot?” He replied that he was not a core member and that he was simply an ordinary worker. He did not dare to protest. Mr. Koumjian asked whether anyone tried to recruit him in a conspiracy against Pol Pot, which Mr. Rumly denied. He fled “when Hor was about to arrive.” They did not dare to stay at the district office. Some escaped to their homes and some people fled to nearby areas.

Mr. Koumjian asked for clarification, since Mr. Rumly had said that he had attended a meeting with Hor. Mr. Rumly recounted that when he returned, Meng was appointed, and three months later there was a meeting. He left Trea in late 1978. At that time, “we all fled into the forest, because we heard that the Khmer Rouge gathered people and walked away with them.” This was around one month before the Vietnamese arrived.

Mr. Koumjian asked how many Cham people were living in the five Trea villages at the time. Mr. Rumly replied that he “could not estimate.”

Mr. Koumjian set a different focus to the line of questions and turned to the treatment of the Cham. He asked whether he had ever heard someone talk about the Cham. He replied that there was a regional security guard who wanted to meet Chhean at the time that Mr. Rumly worked under Chhean. The latter was gone at the time, so the security guard spent the afternoon with the witness. The security guard wanted to know what had happened to the Cham. Mr. Rumly had told him that they had been evacuated to the East Zone and that only 15% were left in the villages. “And he told me that those Cham people would be smashed.”

Mr. Koumjian wanted to know whether this security person knew Mr. Rumly’s ethnicity at the time, which Mr. Rumly denied. Mr. Koumjian then asked whether Mr. Rumly knew “why there was a plan to smash the Cham.” The witness did not know.

Mr. Koumjian asked when these 80-85% of Cham people had been transferred from Trea to the East Zone. He replied that they were told that they would be sent to Battambang province to harvest rice, since there would be enough to eat there. Mr. Koumjian asked whether the people were sent away before April 1975 or after. Mr. Rumly said that it was in late 1975. Mr. Koumjian then wanted to know what happened to the hakims. He answered that the hakims were arrested in early 1975 .They were detained in Krouch Chhmar District in Spean Ta Bouan. They had disappeared ever since.

Mr. Koumjian then inquired about “hadjis”, the people who made the trip to Mecca, and had prominence in Muslim commune. Mr. Rumly recounted that there were hadjis before April 1975 in Trea Village. He estimated that there were around ten of them. When Mr. Koumjian asked what happened to these hadjis, Mr. Koppe objected, since he said that the Prosecution was limiting its question to after 1975, whereas there was plenty of evidence that arrests and possible killings also took place before that date. To make an artificial distinction between these dates brought this “witness into troubles” who might feel forced to answer that the events he witnessed took place after April 1975. Mr. Koumjian responded by saying that counsel would be free to ask about the period before April 1975, but he would focus his questions on the relevant time period. As for the allegation that the witness felt forced to answer questions in a specific way, Mr. Koumjian addressed the witness directly: “Mr. Witness, do you feel intimidated by my questions, Sir?” The witness responded: “No, I did not feel that I was intimidated by your questions.”

As for the hadjis, only one survived the Khmer Rouge regime. Before April 1975, there were three religious leaders in his village. They were arrested and Mr. Rumly has never seen them again. The three teachers were Tosle Ma, who had gone to study in Egypt, Tho Lea Kho, who had studied in Malaysia, and Ibrahim, who had been trained in the village. All of them taught in Trea village. All three were arrested in approximately early 1975.

Mr. Koumjian turned to the next topic and inquired whether all of his five siblings survived. Mr. Rumly said that “of my five siblings, only one was killed.” The sibling who was killed was his first brother. “He went to Vietnam, and when he returned, the Khmer Rouge arrested him. And then he disappeared until now.” In 1973, he went to Chro Mouh Chrouh Province and when he returned, they arrested him. His siblings were all living with him. “Did you do anything to protect them?” He replied that he “did not have the ability to protect all of them.”

Turning to the Islamic burials, Mr. Koumjian wanted to know whether the Muslim population of Trea village followed Islamic traditions regarding burials, such as washing and cleaning them and burying them within a day after the person’s death. The witness recounted that before 1975, and nowadays, “all parts of the bodies had to be washed” and the fingers were rested on the chest. The Khmer Rouge “did not have interest in that kind of tradition.”

Mr. Koumjian then asked whether the Cham language was widely used before 1975, which the witness confirmed. After this date, “Cham language was not allowed to speak”. However, “the ban was not that strict. At home, we could secretly use our language.”

Next, Mr. Koumjian wanted to know whether cadres from any other zone than the Central Zone ever arrived. Mr. Rumly said that “there were two strange people. They spoke with accents, and they came from the Central Zone.” He said he was not aware of cadres arriving from any other zone. When Mr. Koumjian asked about cadres from the Southwest Zone, Mr. Rumly said that there was a man and a woman. One of them was called Trym. Trym took the position of the commune chief. However, he was “usually not stationed within the commune office.” He would come to the commune once in a while.

Oral submissions regarding disclosures

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

After the break, the President announced that oral submissions would first be heard before Mr. Rumly would resume his testimony. Yesterday, the International Co-Prosecutors had indicated that new disclosures were underway. They had proposed the postponement of witness2-TCW-938, who was scheduled to be heard on Monday, until the end of the segment of the Cham before the hearing of 2-TCE-95, since the disclosures might be relevant for this witness. The President wanted to know whether this also impacted 2-TCW-987 and 2-TCW-894. Moreover, he announced that the International Co-Investigating Judges had classified 2-TCW-938 and 2-TCW-894 as falling into category-C witness. The President said that the chamber was awaiting the Co-Investigating Judges to indicate the conditions under which the witnesses could be heard. He then gave the floor to Mr. Koumjian to clarify the issues.

Mr. Koumjian said that there had been an order on December 18 with a motion. For the documents indicated in this motion, the Co-Prosecution needed time to go through them. Some of them might relate to 2-TCW-938, such as witnesses mentioning the witness’s name and an investigative report.

Judge Fenz asked how many weeks the Prosecution would still need to go through the material. Mr. Koumjian replied that he could give an answer at the end of the day.

The President said that the challenge was that the Chamber had scheduled the hearing of the witness on Monday. The President asked whether the documents were also relevant to 2-TCW-988, 2-TCW-987 and/or 2-TCW-894. The Chamber would schedule the witnesses accordingly. The Chamber needed to know now, since WESU needed to be informed. Mr. Koumjian clarified that the Co-Prosecution did not intend to use any of the documents for 2-TCW-938, but wanted to disclose them to the defense, since they seemed to be relevant to the witness.

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé took the floor. She said that she requested some clarity. In the annex of the courtesy copy that she had received this morning, five statements were attached. The annex indicated relevance of the statements and mentioned that four of the five statements might be subject to a Rule 87(4) motion. She said that she got the impressions that the Co-Prosecutors did not know the content of the documents, which they would have needed to know for a previous request. Moreover, if the Co-Prosecution requested more time, the Defense also needed more time.

Mr. Koumjian clarified that the documents could be relevant to 2-TCW-894, but not to 2-TCW-988 and 2-TCW-987. He further explained that they did intend to make a motion to admit the documents before the chamber, but not to use the documents for the upcoming witness. Moreover, when making the motion to disclose the documents, they had used different criteria for disclosure, since there had been a decision by the Chamber since. They now needed to determine whether the evidence was exculpatory and whether they intended to use these before the Chamber.

The President then asked whether any issues arose if 2-TCW-988 and 2-TCW-987 were moved to the beginning of the week.

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud said that they would be ready to put questions to 2-TCW-998 and 2-TCW-987 at the beginning of their testimonies.

Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe said that he had not had time to read the relevant information indicated in the e-mail. He said that 2-TCW- 987 could Kang Meas District in Sector 41, while the other witness was more in a position to testify about events related to Kampong Siem. If 2-TCW- 987 could only give factual evidence, Mr. Koppe was of the view that they could proceed to question him. However, the other witnesses related to chain of communication in Sector 41 and more particular to events in Kampong Siem. This would make it highly problematic to continue with the testimonies of these witnesses in light of the disclosures.

Another way to proceed was to continue in the way that they had proceeded with 2-TCW-1000. The Prosecution could start examining 2-TCW-938 and then resume his testimony at a later stage. Ms. Guissé remarked that she understood that the Co-Prosecutors would not find any new material that should be disclosed or tendered into evidence with regards to 2-TCW-987. However, she said that there was a link between this witness and 2-TCW-938. She further stated that 2-TCW-988 was the least problematic witness and asked whether it was possible to call that witness before the others.

Judge Fenz said that rule 87(4) requests that came in a couple of hours before the hearing started were not desirable. Mr. Koumjian replied that they did not intend to use this for the witness, but merely to disclose them.

The President said that more information should be provided by the Co-Prosecution in the afternoon.

Religious practices during the Khmer Rouge

The floor was then granted to the Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers to resume the questioning of the witness. Mr. Pich Ang gave the floor to counsel Ven Pov. Mr. Pov inquired about the mosque in the commune and then asked whether there were any pagodas in the commune, which the witness confirmed. There was one in another village. From 1975, there were no Buddhist monks in the pagoda. There was nothing in the pagoda, but sometimes it was used as a base for mobile units.

Civil Party Co-Lawyer Ven Pov

Mr. Von quoted from a document, and asked whether ordinary people were indoctrinated or cadres.[1] The witness replied that first it were only cadres, but from 1975 onwards, also ordinary people were indoctrinated.

Turning back to the topic of the invitation for the village and unit chiefs to come to a meeting, he asked how many meetings were organized each month. The witness replied that they were not organized frequently and took place once or twice a month. The commune chief frequently went to the work sites. Mr. Pov then wanted to know who taught him to make reports. He replied that the commune chief first told him what a report was. Mr. Rumly’s task was to make administrative reports, in particular what the instructions were. The monthly report was sent further to the district level.

He then inquired whether Cham were only evacuated from his village or from the whole of commune. He replied that the person had asked him who a house belonged to, to which he had answered that it belonged to Cham who were already evacuated. The evacuation was forced. After the 7th of January, a number of Cham returned. Asked about marriages, he replied that he had heard about this during the Khmer Rouge, and he himself had been married under the Khmer Rouge. There were one or two wedding ceremonies that were organized during these years. During the first wedding ceremony, only four couples “were arranged.” In the second ceremony, more than 20 couples were married. Some of them were voluntary, other were forced. The marriages were not mixed but between Cham or between Khmer people. There were no ethnic Vietnamese who lived in his commune from 1975 until 1979.

After 7 January 1979, he returned to his village. Around 500 families came back. With this, Mr. Pov concluded his questioning.

The Khmer Rouge in Trea village

The floor was granted to the Nuon Chea Defense Team. Mr. Koppe referred to the witness’s statement, in which he had said that the Khmer Rouge arrived in 1970.[2] He confirmed that this was correct. Mr. Koppe asked to describe the situation: who exactly arrived? Were they known as Khmer Rouge? Who was in charge of the district? He replied that they did not know they were Khmer Rouge in the beginning, since they represented themselves as the National United Front , who were mixed with the Vietnamese. Mat Ly was the Commune chief at the time, but he could not remember the name of the commune chief. Mr. Koppe asked what the role of the Vietnamese was at the time. The Vietnamese who arrived in the village were mostly engaged in military activities.

Mr. Koppe asked who Mat Ly was. Mat Ly was a Trea Villager. Mr. Rumly recounted that he was first located at a rubber plantation, but then relocated to the Trea Village. Mr. Koppe asked whether he also knew another Mat Ly who had a high position in the East Zone, who became a member of the National Assembly. The witness replied that he had heard his name but had never seen him. Mr. Rumly confirmed that these were two different Mat Lys: Rap Mat Ly was a teacher in Trea Village. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that the witness himself never became a member of the CPK or a Khmer Rouge cadre. The witness replied that he “never got involved with the CPK”. Mr. Koppe asked whether a number of Cham people joined the revolution. He replied that around 20 Cham youths joined the revolution in 1970. “It was probably the Khmer Rouge revolution.” Mr. Koppe asked whether the other Mat Ly, who Mr. Rumly had never met, was the highest ranking Cham within the CPK. Mr. Rumly said that he did not know the person and had only heard about his name.

Mr. Koppe read out an excerpt Man Sen, who had given an interview to the investigators of the Co-Investigating Judges, but also to Ysa Osman.[3] This witness had said that arrests of villagers of Svay Khleang, a sub-district in Krouch Chhmar, began in late 1973. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether the witness was able to observe that arrests were already made in late 1973. Mr. Rumly asked whether these arrests took place in Khleang or Trea. Mr. Koppe clarified that the witness had referred to Khleang, but that his question referred to Trea. Mr. Rumly confirmed that there had been arrests in 1973. He replied that he did not know who made the arrests. He saw “full loads of soldiers in a truck”. Mr. Koppe asked whether Mr. Rumly recalled any arrests in 1974 in Trea Village. The witness replied that the arrests took place once in a while in 1974. “One or two people were arrested.” Mr. Koppe read out another excerpt of the same witness’s interview, who had said that arrests increased in late 1974, finding a peak when more than 200 people were arrested at once. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether the arrests increased in 1974 in Trea Village. Mr. Rumly said that the arrests did not increase at this time.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Rebellion

After the lunch break, the President asked Mr. Koumjian to clarify some of the issues that came up this morning. The total number of Written Records of Interviews that had been authorized for disclosure were an additional 124. Four of those had been disclosed informally yesterday by way of e-mail that related to the Cham. The remaining 120 had to be analyzed. He estimated to be able to go through these documents within two weeks. Around thirty of these statements seemed to relate to the Vietnamese segments.

The President then announced that first witness would be 2-TCW-987, followed by 2-TCW-988, 2-TCW-928, then 2-TCW-894, and lastly 2-TCW-938.

Mr. Koppe resumed his line of questioning and asked whether he knew that in December 1974, arrests of Cham leaders provoked a rebellion, which the witness denied. “There was no rebellion in December.”

Mr. Koppe said that Mat Ly – the one that the witness did not know personally – had told Ben Kiernan about a rebellion in late 1974.

The witness recounted that there was a minor rebellion in Trea Commune in late 1973. 20 people were arrested and taken away on a truck.

Mr. Koppe then referred to an excerpt by Kiernan, in which Mat Ly had talked about a rebellion.[4] Mr. Koppe asked whether this was maybe the same rebellion. Mr. Rumly replied that he was not aware of this matter.

This person had further said that by 1975, arrests had been carried out indiscriminately.[5] According to this witness, anyone who was thought to be connected to the White Khmer Movement, the Khmer Sar movement, was arrested. Mr. Koppe asked whether he had heard of this movement. Mr. Rumly replied that he did not know about the Khmer Sar. He had heard about the movement in late 1974, but he did not know about who they contacted and where it originated.

Mr. Koppe moved to what he called the second rebellion and asked whether this rebellion occurred in October 1975. The witness replied that he never said that there was a rebellion in Trea Village in 1975. Instead, there had been a small rebellion in Trea Village V in 1973. However, there had been a “crack-down” in 1975.

This prompted Mr. Koppe to refer to Mr. Kiernan’s book again.[6]

Mr. Kiernan had quoted Francois Ponchaud, who had talked about a rebellion in Trea Village. Mr. Koppe asked whether this was something that the witness knew anything about. Mr. Rumly replied that he had never heard about. Mr. Koppe asked whether he had heard what had happened in Koh Phal and Svay Khleang village, which the witness confirmed. He had heard of a crackdown.

Mr. Koppe read out another excerpt of the same witness as before. Mr. Koppe asked whether this sounded familiar: people calling for a rebellion with drums and the crackdown of the rebellion the following day, involving heavy artillery and boats. Mr. Rumly replied that the people in Svay Khleang had shot a commander, which is why there was a crackdown. He had heard the heavy weapons, since Svay Khleang was ten kilometers away. He saw the soldiers: “they wore quite blue or green uniforms” and he heard people saying that they were soldiers from the region. The witness recounted that people “on the list” were arrested. The soldiers went around to arrest people from their houses.

Mr. Koppe asked how people could make a distinction between forces from the district – Krouch Chhmar – on the one hand, and forces from the Zone instead. He replied that he could not make such a distinction.

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Mr. Koppe then referred to witness 2-TCW-997 (Sao Sammek), who could not testify.[7] This witness had said that battalion 55 of the East Zone was used to “suppress the Cham rebellion.” The witness replied that he did not know the battalion and only knew that the soldiers came from the sector.

Mr. Koppe asked whether he had ever heard that Hun Sen had been a commander of the battalion and involved in crashing the rebellion in Svay Khleang , which the witness denied. There was no shooting during the crackdown, “so there were no casualties.” Around 50-60 people were arrested.

Mr. Koppe then said that Mat Ly had said that thousands of people died during the crackdown and that only around 20 % of the families survived.[8] When Mr. Koppe asked for a reaction to this statement, Mr. Koumjian interjected and said that the record may be confused, since the crackdown in the cited documents referred to another village than Trea Village, which is what the witness was talking about. Mr. Koppe said that it had been seen as one rebellion. Mr. Koumjian said that this was simply Mr. Koppe’s assumption and that it looked like there was no rebellion to overthrow the government, but merely a resistance to the arrests of Cham. Mr. Koppe responded and said that this Co-Prosecutor seemed to be the only person to doubt that there had been a large scale rebellion. Judge Fenz said that the question was which village the witness referred to. Mr. Koppe replied that the distinction was an artificial one. He then repeated his question. The witness replied that he did not know what happened in Koh Pal or Svay Khleang, because “they were far from each other”. They were ten kilometers away from each other, and it was not easy to travel.

Mr. Koppe quoted Senator Ouk Bunchhoeun, who had been “Number 2 of Sector 21” and who had said that the Cham movement attempted to create a state within a state.[9] Mr. Koppe asked whether the witness had ever heard about this, which he denied.

Mr. Koppe inquired about the Kbal Sar, a movement which had been described as being unsuccessful in the end. Mr. Rumly said that he had heard about the White Khmer movement, but did not know about its origin.

Mr. Koumjian interjected and said that it was indicated later that this information stemmed from confessions. Mr. Koppe argued that this would be perfect reason to ask him to appear, something that the Trial Chamber refused on December 18 2015.

The President said that the information Mr. Koppe had used was clearly obtained through confessions, which was not permitted. He prohibited Mr. Koppe to ask this question.

Mr. Koppe moved on and asked about Mat Ly, who spoke about the practice of religion. E3/7821, He had said that religion was only prohibited in 1976. Mr. Rumly replied that the religion was banned after the Khmer Rouge took over Phnom Penh.

Mr. Koppe then asked whether the witness knew that Mat Ly was not only a Member of Parliament for Kampong Cham, but also the personal supreme counsel of the king. Mr. Rumly said that he did not know what Mr. Koppe was talking about.

Witness Sos Rumly

Mr. Koppe asked whether he knew who the leader was of the East Zone in 1975, which the witness denied. “I knew only people at the village and commune level.” Mr. koppe asked whether this meant that he had never heard the name Sao Phim. Mr. Rumly said that he had heard of him and knew he was working at the Zone level, but did not know at what level Phim was working.

Mr. Koppe again read out an excerpt of Ben Kiernan, who quoted Hem Samin saying that the Zone Secretary Sao Phim was blamed for the suppression of the Cham. The witness said that he did not know about this, since “news was very restricted. It was not like nowadays.”

Mr. Koppe asked whether the bones that the witness had seen belonged to the victims of the repression of the rebellion. The witness replied that the pits started to be dug in mid-1978. After the liberation, he saw the pits. Before this, “there were no such pits.”

The floor was then given to Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé. She turned to the ban of practicing Islam and asked whether he had the right to practice the religion before the Democratic Kampuchea regime. Ms. Guissé asked whether this ban did not only target Muslims, but all religions. Mr. Rumly confirmed this. Ms. Guissé asked what the situation of his family was when he was appointed leader of the youth group. He replied that his family was a poor family. He confirmed that this factor played a role in his appointment. The village chief was Sar Mat No at the time. He was Cham. She further asked whether this person was the one who told him that he was appointed because of his poor class. He replied that he was not told as such at the time. He learned this from the youth chief. Ms. Guissé asked whether there were any relations between the Cham and the Khmer villages. He replied that they had a good relationship and “we were in solidarity.”

Ms. Guissé asked whether it was correct that a Muslim person had the right to marry someone from another religion, but it had to be to someone of the Catholic faith or the Jewish religion. She asked whether she was correct that the marriages before 1975 were therefore solely amongst Cham people, and not between Cham and Khmer people. He replied that there were only a few cases.

Ms. Guissé then asked whether Hor had another name, which the witness did not know. He saw Hor twice: the first time when he arrived and the second time when Hor convened a meeting and the commune chief asked the witness to accompany him. He did not know whether Hor had a motorbike. In the meeting, there was a discussion on agricultural production. Ms. Guissé asked when the discussion about purging the Cham took place. He replied that it was in 1977. He knew that the person was a security chief, because he showed him a letter, wanted to see the commune chief, and told him that he was the security chief. Chhean was the commune chief at the time. Ms. Guissé said that the next question might be naïve, but that she thought the witness’s appearance looked North-African and not like of Khmer origin. He replied that they did not ask him about his past background, because he “spoke Khmer very clearly.”

Arrests

International Khieu Samphan Defense Team Anta Guissé

After the break, Ms. Guissé resumed her line of questioning. She asked whether he knew who the security chief’s superior was, which he did not. Ms. Guissé then inquired whether Hor had a deputy, and if he did, what his name was. Mr. Rumly said that he could not recall. He “did not dare to go close and build a relationship with them.” Ms. Guissé asked whether he had ever heard about an incident, during which a member of the commune had allegedly been wounded. Mr. Rumly replied that he did not know about this. This prompted Ms. Guissé to refer to witness Ban Siek’s testimony. On October 5 2015, he had said that militiamen shot someone from the sub-district committee in Krouch Chhmar.[10]The witness had not heard of such an incident.

Ms. Guissé turned to the next topic. Ya Yorb was the chief of the fishing unit from 1974 onwards. When Hor arrived in 1978, he took Yorb away. She then asked whether his siblings were working during the Democratic Kampuchea period and if yes, what their exact jobs were. He replied that one was working in the kitchen and two others in a mobile unit.

Hiding from the Khmer Rouge

Ms. Guissé then inquired about the flight to the forest. He said that it occurred on January 01 1979. He and other villagers fled. He fled because of the Khmer Rouge and not because of the arrival of the Vietnamese. He recounted that he also hid when Hor arrived. Ms. Guissé then asked whether she understood him properly that other people also fled back then. He clarified that he hid in the forest and did not flee. Ta Yorb also hid. There were both Khmer and Cham people who hid. He hid for around one or two days when he heard that the village chief and deputy chief were arrested. He did not know why he was proposed to be clerk.

She then asked for clarification regarding the pits that he had seen. She asked whether the flood he had mentioned occurred before or after he had seen the pits. He said that the flood occurred in September 1978.

The President adjourned the hearing at 3 pm. It will continue Monday 11 January at 9 am with the testimony of 2-TCW-987 in relation to the treatment of the Cham people.

[1] E3/5196, at 00204456 (KH), 00223087 (EN), 00274739 (FR). [2] E3/5196, at Question 1. [3]E3/5205 and E3/7675, at 00221859 (EN), 00293924 (FR), 00221852-53 (KH). [4] E3/1593, at 00678635 (EN), 00637765 (KH). [5]E3/7675, at 00221853 (KH), 002939924 (FR), 00221859 (EN). [6] E3/1593, at 00678636 (EN), 00639034 (FR), 00637770 (KH). There was a confusion with the ERNs that the Co-Prosecution had and the Defense provided. It corresponds to page 265 . [7] E3/5261, at 00274336 (EN) 00285329 (FR), 00250943 (KH). [8] E3/72, at 00441577 (EN), 00611784 (FR), 00229128 (KH). [9] E3/387, at 00350206 (EN), 00441418-19 (FR), 00379486-87 (KH), [10] Transcript of hearing, Ban Siek, October 5 2015, at 15:05.

Featured Image: Witness Sos Rumly (ECCC: Flickr).