Witness Confirms Disappearance of Vietnamese Husband and Neighbors

Today, Civil Party Daung Oeun told the Court how her ethnically Vietnamese husband Chuy was taken away by the Khmer Rouge in 1977 and never returned. A significant part of both defense teams’ questioning focused on what her husband was doing before the Khmer Rouge arrived. They submitted – based on this witness’s previous testimony and other statements – that he had secretly dealt with opium from Vietnam. Ms. Oeun repeatedly insisted that she did not know anything about such an allegation and that her husband had only sold chicken and ducks.

Next, the testimony of witness Prum Sarat began. He had been a combatant for the Khmer Rouge from 1970 onwards and later commanded a military company with 110 members, before taking over the command of a vessel under the navy.

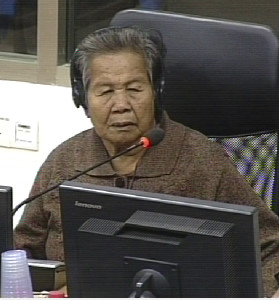

Witness Daung Oeun

At the beginning of the session, the Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn announced that the testimony of 2-TCCP-869 would be heard today. He further said that Judge You Ottara was absent due to urgent personal matters. He would be replaced by Judge Thou Mony. The Trial Chamber Greffier then confirmed the presence of all parties, with the exception of National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel. Nuon Chea was granted the right, as usual, to follow the proceedings from the holding cell. Witness 2-TCW-1009 was on the reserve.

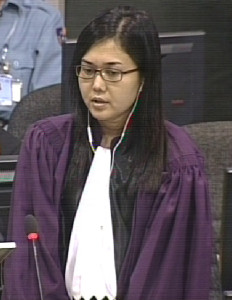

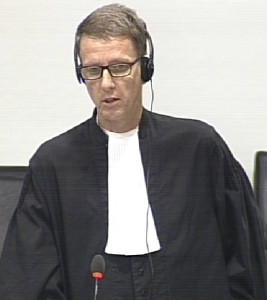

National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang

Civil Party Daung Oeun alias Din Oeun was born in Svay Antor District, Prey Veng Province and lives in Pochendam Village today. After confirming the number and accuracy of her Written Record of Interview, the floor was granted to National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang. He asked where she lived before 17 April 1975. She replied that she lived in Pochendam, which was also her native village. She was married already to Chuy since the Lon Nol regime. The house Chuy was living in was Khmer, but he was Vietnamese and lived with Vietnamese people. His native village was Peam Village. He spoke Vietnamese fluently, but “did not speak [Khmer] clearly.” They lived together “until the time he left.” He was tasked to carry buffalo and cow dung to fertilize the rice fields. They have one child. His or her name is Kim Va alias Ky Mien. Her husband’s full name is Tep Yun. The family name of their child was from her husband’s father. When asked why her daughter had an alias, she recounted that she stopped calling her Kim Va “because I was afraid that they would take away my child to be killed.” The daughter is still alive today and 35 years old.

Mr. Ang then inquired whether she heard any information that Vietnamese people had to return to Vietnam, which she confirmed. However, her husband refused to go: “to live or to die, he would remain in Cambodia.” Ta Ky, Yeay Man and their children went to Vietnam. The man returned to Cambodia after the collapse of the Khmer Rouge and died.

Disappearance of her husband

Mr. Ang turned to the fate of her husband and asked what he did before his disappearance. She replied that he was assigned to cut rumpeak vine, after which he disappeared. She could not remember the exact year when he disappeared. It was during the harvesting season. When she returned home from the harvest, he had disappeared. “I did not know at the time where he went to.” Her mother had told her that her husband had been taken away. Her mother did not know where they had taken her husband to. After hearing this, she returned to work. He was “walked away from my house, this is what my mother told me.” One person walked her husband away. Her mother told Ms. Oeun’s husband that he had to return immediately. He replied that he would come back soon, but disappeared ever since.

She recounted that Lach Ny’s family and the children were sent away as well, while only Lach Ny was spared. The five or six children were sent away together with the mother. She did not know Lach Ny’s wife’s name. She was ethnically Vietnamese and “spoke not clearly.” Lach Ny’s wife sold vegetables that she had bought at the market.

Another Vietnamese person who disappeared was Ngang, who had been taken away first to “cut rumpeak vine”. His children were not taken away. She knew that he was Vietnamese, because he “did not speak the [Khmer] language clearly.” She did not know whether Ngang’s parents spoke Vietnamese, because they lived far away from her. She never spoke to him.

Ngang was the first one to be arrested, then Lach Ny, and her husband was the last one to be arrested.

Her husband sold chicken. “That’s the only business that we did at the time.” She denied that her husband sold opium. When asked whether they had a decent living at the time, she said that it was difficult. “We did not have enough to eat. We were blamed. We were assigned to work with no free time.”

Civil Party Daung Oeun

Turning to the next topic, Mr. Ang inquired what work she did during the Khmer Rouge regime. She replied that she was assigned to dig soil, dig canals, harvest and transplant rice. Her mother took care of her children during that time. Her husband helped looking after their daughter before he was taken away. “And he always held the hand of the child to the working place.” He would take her with him during lunch time. When he was taken away, the child was left with Ms. Oeun’s mother. She had another child called Meang, but he was taken away and killed during the Pol Pot time. He asked for gasoline and killed. This was a child from a former marriage. Her son “accidently made a fire out of the gasoline and a secret lighter”, which is why he was arrested. Her husband Chuy had been arrested first and only later was her son arrested.

Mr. Ang then wanted to know whether she knew that her husband had a position as a soldier before he married her. She replied that she did not know whether he was a soldier “in any other society. […] He never told me that he was a soldier.”

Mr. Ang asked whether there was any discrimination against her husband. She said that her husband and her child were both taken away and killed. “I miss them and I feel pain in my heart.” Mr. Ang repeated his question. She said that there was no discrimination against him in the commune against her husband. With this, Mr. Ang finished his line of questioning.

The floor was granted to the Co-Prosecutors. Assistant Prosecutor Andrew Boyle started his questioning by inquiring when she renamed her daughter. She explained that she started calling her daughter by a different name, because she was afraid her daughter would be “smashed.” She confirmed that this was after the arrival of the Khmer Rouge in her village. Villagers had suggested renaming her daughter, as she might be taken away as her father. “The name Kim Va may have something to do with the father”, she recounted, which is why she changed it.

Turning to his next line of questioning, Mr. Boyle wanted to know when the Khmer Rouge entered her village. She said that it was in 1977. This prompted Mr. Boyle to read out a transcript of the testimony of Theng Huy alias Theng Phal, who had said that the Khmer Rouge arrived in 1972 or 1973.[1] Mr. Boyle asked whether this refreshed the Civil Party’s memory. She said that she did not know about other statements, but knew that they arrived in 1977.

Persons of authority

She denied that the Khmer Rouge put someone in power there. Mr. Boyle asked about someone called Horn, who she recalled to have been a militiaman. He remained in power when the Khmer Rouge entered the area. He passed away by now. His wife and children, however, survived. Mr. Boyle asked whether the name Seng meant anything to her. She replied that Seng was chief of the militia. However, “he was not a native villager in my village. He came from another village.” She could also recall Chhem, who was the commune chief. She could not recall the name of Chhem’s deputy. Mr. Boyle then inquired whether the name Mut meant anything to her, which she confirmed. “However, Mut had worked much longer than Chhem.”

Mr. Boyle pointed out that Theng Huy alias Theng Phal had said that Mut was the deputy.[2] She confirmed that this refreshed her memory. “Mut had worked before Chhem.”

Mr. Boyle further wanted to know whether she remembered someone called Ngoy. She replied that she was not familiar with this name.

Mr. Boyle said that her cousin Lack Kri had testified that Ngoy was the chief of security in Svay Antor district.[3] She insisted that she could not remember this person.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

After the break, Mr. Boyle resumed his line of questioning. He inquired whether the Khmer Rouge took any steps to identify who was of Vietnamese ethnicity, which she denied. Neither did they ask them. This prompted Mr. Boyle to refer to her DC-Cam interview, in which she had said that they collected statistics and went from house to house to ask who was Vietnamese.[4] She replied that she could not remember this.

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

Mr. Boyle asked whether it refreshed her recollection as to when her husband was taken away if being told that it took place in 1977. Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe objected and said that she herself had said it took place in 1978. The President said that questions should first be asked openly and if that was unsuccessful one should refer to documents. Mr. Boyle referred to her Victim Information Sheet, in which she had said that her husband had been taken away in the rainy season 1977.[5] When she recounted that it was during the harvesting season, the President interjected and explained to her that the question referred to the year. She confirmed that it was in 1977, but she did not know which month.

Mr. Boyle referred to one of her other statements, in which she had indicated that she saw him being put on a horse cart.[6] She replied that she did not witness the event itself and therefore did not know whether he was put on a horse cart or not. She said that her mother did not mention which person took away her husband. She replied that there was only one militiaman who walked him away. Mr. Boyle wanted to know whether she ever asked a militiaman whether they would also take away her daughter. Ms. Oeun replied that her daughter was not taken away. “I did not seek more clarification on the issue after my husband was taken away. As I said, I did not bother” to inquire about her daughter.

Mr. Boyle referred to her interview, in which she had said that she asked the militiaman whether they would take away her child, too, and in which she had said that they gave the answer that the child would not be arrested if the mother was Khmer.[7] She replied that it was indeed the case that the child would be taken away if the mother was ethnically Vietnamese, but not if she was Khmer. Despite this fact, she tried to conceal the background of her daughter. She did not know about a specific case about when the child would be taken away because of the mother.

When Mr. Boyle asked whether she actually believed that her husband was taken away to cut rumpeak vine, Mr. Koppe objected and said that this question led to speculation. The objection was overruled. When the question was repeated, she did not shed much light on the matter.

Mr. Boyle read an excerpt of her interview, in which she had said that she did not believe that her husband was ordered to cut rumpeak vine, since someone else had been taken away before.[8] She replied that it was her conclusion that he would not come back after being told that he was ordered to cut the vine.

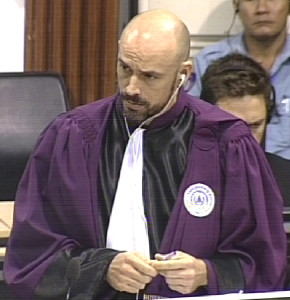

Assistant Prosecutor Andrew Boyle

Asked about any possible offenses that her husband might have committed to trigger his arrest, Ms. Oeun said that her husband had not discussed such a matter.

Mr. Koppe objected to the word “arrest” when Mr. Boyle asked whether she had heard any Khmer Rouge leaders insult the Vietnamese before her husband’s arrest. Mr. Boyle replaced the word arrest by the words “taken away”. She replied that she had not heard any discussions.

Mr. Boyle said that she had heard them using derogatory and insulting words towards her husband before.[9] She denied this and said that they did not use such derogatory words in front of her.

Disappearances of other Vietnamese people

Mr. Boyle moved on and asked about Mr. Ngang. He wanted to know whether she witnessed when Mr. Ngang was taken away, which she denied. She replied that she heard that he was also taken away to cut rumpeak vine. Ngang’s wife was “pure Khmer.” She now lives in another location, but at the time she was living in the same village. Ngang’s wife was not taken away.

Mr. Boyle turned to Lach Ny’s wife and asked whether the name Sum San refreshed her recollection. She said that she did not know the name. She did not know where Lach Ny’s wife was gone to. She knew that she was taken away, because she “simply disappeared.” Lach Ny’s wife was amongst those people. “She was not spared.” Her children were also taken away, because her mother was ethnically Vietnamese: “And they would not spare a single child.” She never saw those children again.

She confirmed that she attended meetings, but she said that she could not recall details about those meetings. She said that they did not discuss the fate of those who were of Vietnamese ethnicity. Mr. Boyle referred to her DC-Cam interview, in which she had confirmed that they “created bad feelings” about Vietnamese people in meetings.[10] She could not recall any details. She did not know anything about other villages than hers.

Mr. Boyle asked whether she ever heard about a pagoda near her village called Wat Chhas or Wat O Kandal. She replied that she had not heard about this pagoda. She confirmed having known this pagoda. She did not know what the pagoda was used for.

Mr. Boyle wanted to know whether she knew someone called Try in her village. She said she had a cousin called Kry. Mr. Boyle said that he did not refer to her cousin, but to someone who owned a horse cart in her village. She said that the person who owned the horse cart was called Kry, but died a long time ago. She knew he had a horse cart, but she did not know whether he was ordered to transport people. With this, Mr. Boyle finished his line of questioning and handed the floor to his national counterpart.

National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Ms. Son Chorvoin wanted to know whether her husband spoke Khmer clearly. She replied that he had difficulties speaking Khmer. She could not remember what month or year her husband came to live in her village. It was during the Khmer Rouge regime.

Ms. Oeun said the Vietnamese people got along well with the Khmer villagers and lived in harmony. She lived in her village since she was born. There are no Vietnamese families living in her village. None of the Vietnamese families returned.

National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Song Chorvoin

Ms. Chorvoin then wanted to know why she thought that they did not return when being ordered to cut rumpeak vine. She said that it was her feeling and “indeed, no one returned.” Her husband was tasked to carry cow and buffalo dung during the Khmer Rouge regime. Before this, he was a “petty merchant”, and sold ducks and chicken. She did not know what he did prior to that.

When Ms. Chorvoin asked whether her husband held any position before the Khmer Rouge, Mr. Koppe interjected and said that precise years should be used. Ms. Chorvoin asked whether it was correct that her husband was taken away in 1977, which Ms. Oeun confirmed. Her husband was taken away around a month after the arrival of the Khmer Rouge. She never moved anywhere else.

Ms. Chorvoin pointed out that the Khmer Rouge entered the area in early 1971 or 1972, while Ms. Oeun said they entered the area in 1977. Ms. Oeun insisted that it was in 1977. Ms. Chorvoin asked whether Khmer Rouge cadres ever mentioned the Vietnamese people living in the village in meetings, which she denied – she had never heard them mentioning the Vietnamese. The President took the opportunity to adjourn the hearing for a break.

Chuy’s duties

After the break, the floor was granted to the International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel. Victor Koppe started his line of questioning by putting some follow-up questions to the Civil Party. He asked whether it was true that she had said that her husband sold “sold life-stock, such as duck and chicken”, which she confirmed. Mr. Koppe asked whether he traded in other things than life-stock. She denied this. She also denied his selling medicine or opium. “He only sold life-stock, no other business, and that was it!” She confirmed that she was sure about this.

This prompted Mr. Koppe to put an excerpt of her own interview, during which she had said that her husband sold opium.[11] She said that she never said this. She did not know what he sold, only that he sold life stock: “There was no opium at the time!” Mr. Koppe referred to her sister’s statement, who had said that the Civil Party’s husband smuggled medicine.[12] Ms. Oeun said that she did not know about this.

Mr. Koppe then wanted to know what her husband did before coming to Cambodia. She confirmed that he had been in a military unit in Vietnam before and also confirmed Mr. Koppe’s follow-up question whether this meant that he had been a Vietnamese soldier. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he belonged to the Viet Cong or to the opposite party. She said that she did not know which side he belonged to. Mr. Koppe then wanted to know whether he was a “communist with not very much sympathy for Americans” or Lon Nol soldiers. She said that she did not know. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that he had family members in Saigon. She said that he indeed had family members there, but she did not know when his family members moved there. His birthplace was Peam as was the birthplace of his parents.

Vietnamese relatives

Mr. Koppe moved on to the next topic. He wanted to know who she referred to when saying that “they were Vietnamese in his house.” She replied that they were not in her house. “They were other people, not my relatives, but they also lived in the same village.” She confirmed that there were other people living in her house, namely her husband’s niece and nephews. She did not know where they were now. She confirmed that there were Vietnamese family members who lived with them, but she did not know where they went to when they left. She could not remember the year that they returned.

Mr. Koppe inquired whether her husband was the only Vietnamese person from his family who “stayed behind” in Pochendam Village. The Civil Party affirmed this.

Mr. Koppe then wanted to know how she had urged her husband to return to Vietnam and why he refused. She answered that her husband had said that he was willing to die with her in Cambodia to be with her and her child and not willing to go back. “He would prefer to die in Cambodia together with me and my child.”

Discrimination of Vietnamese

Mr. Koppe then turned to the period before April 1975, an era that was referred to as a Lon Nol regime, and inquired about the treatment of the Vietnamese during that time. She replied with the treatment of the Vietnamese during the Khmer Rouge regime. The President clarified that Mr. Koppe had referred to the Lon Nol regime. She confirmed that Vietnamese people were discriminated against during the Lon Nol regime, but nothing happened to them. Mr. Koppe referred to another person’s statement.[13] She confirmed knowing him and said that he was living in her village today. This person had said that the discrimination started during the Lon Nol regime. The Civil Party could not shed much light on that matter.

Mr. Koppe referred to her supplementary submission, in which she had said that her husband was arrested in 1978.[14] She insisted that it took place in 1977 and not 1978.

Mr. Koppe said that the witness Theng Huy placed these events before something called the Sao Phim event. She said that she had never heard about this. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was possible that when referring to the arrival of the Khmer Rouge in 1977, she actually meant the arrival of the Southwest cadres. She said that she might have known something about that and that he might have been involved in this. She said that she knew people were involved in this, but she could not recall any details.

Turning to his next topic, Mr. Koppe asked whether she had ever heard, seen, or experienced gunfire or artillery. She said that she did not go to any area that was referred to as “the fertile land”. Mr. Koppe asked whether she ever had to escape from Vietnamese tanks or artillery, which she confirmed. “I fled to another area, and only after the end of the war I returned to my village. And that was the war that I knew. There [was] heavy shelling in my area, so I had to flee.” The shelling was far away from her village, but she was afraid, so she fled. She fled to the nearby village sometimes.

Turning to his last subject, Mr. Koppe asked whether she could tell the Court how exactly she heard about “this thing” that children of Vietnamese mothers were targeted while children of Khmer mothers were not. She said that Lach Ny’s children were taken away. She did not know where these people were taking them. She never saw them again. She could not shed light on the matter any further.

Her daughter is 35 years old. Mr. Koppe pointed out that Ms. Oeun’s mother had said that Ms. Oeun’s daughter was too small to remember anything. The Civil Party could not shed much light on this matter.

International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

The floor was given to International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé, who inquired whether she remembered having given an interview to DC-Cam, which Ms. Oeun did. She could not recall the date.

Ms. Guissé then read out an extract of Ms. Oeun’s interview.[15] She had indicated that her husband had earned a lot of money by selling opium. Mr. Oeun denied that this took place and said that her husband only sold ducks and chicken. Ms. Guissé asked how she could explain the difference of the two versions.

Mr. Ang interjected and said that the questions were repetitive. Ms. Guissé pointed out that she gave very precise details about the trade of opium and the packaging of opium.[16] Ms. Oeun said that she did not know about this. With this, Ms. Guissé finished her line of questioning.

Victim Impact Statement

I was mistreated, I was forced to do hard labor, to transplant seedlings in the rice fields and my body physically deteriorates until the present time, and the older I get, the weaker I become.

Mr. Ang pointed out that he had requested to put questions to the Civil Party to guide her through the Victim Impact Statement.[17] The President granted him the request.

Mr. Ang asked her how she felt when thinking about having lost her husband Chuy and her son Mon Meang.

I have great pain for the loss and I was forced to engage in all kinds of tasks.”I was used without any break time to engage in earth digging in building dykes, in the rice fields. And t the same time I lost my child and my husband, and that is a great pain for me. And when I think about it, it is vivid in front of me. And I also feel miserable and lonely when I lost my husband. And that is compounded by the fact that I am poor.

She further said that

I could hardly earn a living. And my feeling was constantly was constantly about my husband and my son. I could hardly feed myself from what I earned each day.

Asked whether she had anything to add, she said that

Allow to seek some assistance from the court. I could hardly afford myself with food on a daily basis. I am old and I cannot use my physical strength to earn my living. I also have difficulty walking.

With these words, the testimony of Civil Party Oeun came to an end. The President thanked her and dismissed her. H announced that 2-TCW-1009 would be heard after the break.

A new witness: Prum Sarat

After the break, the President issued an oral ruling on document E382, which was a motion by the Co-Prosecutors to hear 2-TCW-1010 and admit several documents.

The President pointed out that the Chamber had already denied the request to hear 2-TCW-1010.

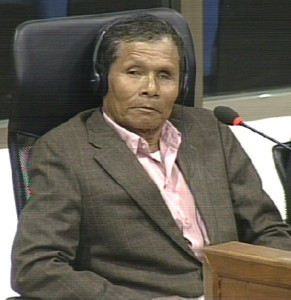

Witness Prum Sarat

The Prosecutor had informed the Chamber that they intended to use the two statements by 2-TCW-1010 in the examination of 2-TCW-1009. Since no objection has been raised, the request was granted.

International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Ms. Guissé said that they had objected. The President said that the decision had already been taken that the two statements could be used to examine the upcoming witness. He then ordered to usher in 2-TCW-1009.

Witness Prum Sarat was born on 1 March 1949. The floor was granted to the Defense Counsel for Nuon Chea. Mr. Koppe started his line of questioning and asked when and where the witness joined the revolution. He said that he joined it in Kampot in 1970. The division was not organized yet. Division 3 came into being in 1973. He left Kampot sector military and joined the military in the Southwest Zone when the division came into division, which was in 1974. The commander of Division 3 was Meas Muth. His division was engaged in the attack on Phnom Penh in 1975. His responsibility was to be engaged in the attack to the East of Tham Phong, which was called Mong Cheng. “I supervised 100 soldiers at the time.” Three battalions made up one regiment. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that there were three platoons in his company. He could not remember how many combatants died in the attack of Phnom Penh.

After Phnom Penh had fallen, he received instructions from the upper echelon to go to the Kampong Som battlefield. They first walked by foot, but after a while there were vehicles. He confirmed that it took them five days to reach Kampong Som. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether there were any attacks from the Lon Nol soldiers during these five days, which the witness denied.

This prompted Mr. Koppe to refer to his DC-Cam statement, in which he had said that there was a clash with the Lon Nol troops at a location who had raised the white flags after a landmine exploded.[18] He confirmed having given such a statement to DC-Cam. He saw the injured soldiers and asked them who got injured.

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Mr. Koppe inquired what it meant if a soldier waved with a white flag. He replied that it meant that the fighting between both sides came to an end. Mr. Koppe pressed on and referred to a statement from a witness who had testified in Case 002/01.[19] This witness had denied any orders to seek out Lon Nol soldiers, since they had surrendered with white flags. This witness had also said in his testimony that they were ordered not to touch those who had surrendered.[20] Mr. Sarat said that his understanding was the same, since a white flag meant that the other side had stopped fighting.

Mr. Koppe asked whether he was aware of any killings of Lon Nol soldiers who had surrendered within his company or within Division 3. He replied that when he travelled from Phnom Penh to Kampong Som, his company did not touch any soldiers, “even a single soldier”, after 17 April 1975.

Mr. Koppe asked whether Norodom Chantaraingsey was a high-ranking soldier. The witness said that he was of Division 13. He had heard of Son Ngog Tan.

When Mr. Koppe asked whether Division 164 became the Navy division, Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde interjected and said that the question was not appropriate. Mr. Koppe rephrased and asked whether the witness became a member of 164, which he confirmed. This took place in June 1975. His division became Navy Division 164. Mr. Koppe said that he had said twice that his division became the Navy Division in June 1976.[21] His division counted around 9,000 men.

Mr. Koppe then wanted to know whether Division 164 was one of several Central divisions. He confirmed that Division 164 was under the command of the Central Army.

Regiment 140 was located in Au Chatreal in Kampong Som. Regiment 140 had around 1,400 men. When they started the division, they had around 120 men who were trained in the navy and were assisted by China. Within Regiment 140, there were battalion 41 until 44. He was within Battalion 44, Company 2. He was the commander of Company 2.

Mr. Koppe said that he had indicated in his interview that they had ten combat vessels, ten partrol vessels, a tanker and four mine sweepers.[22] Mr. Koppe asked whether this was correct, which the witness confirmed. He had 110 men under his supervision.

Mr. Koppe said that he had also indicated having been commander of Vessel 1710, commanding 38 members.[23] He replied that he was supervising the vessels. They wrote the signs of identification for the vessels. He was removed from Company 2 and sent to be in charge of the technical training as the commander of the naval force. There, he had 38 crew members under his command. When Mr. Koppe asked whether this was a promotion for him to become the commander of Vessel 1710, the witness answered that the promotion meant that he had the technical skills required.

Mr. Koppe then inquired whether he recalled whether there were soldiers from the East Zone forming part of Division 164. He replied that there were around 700 soldiers which used to be based in the East Zone.

Mr. Koppe referred to the witness’s DC-Cam statement.[24] He had said that 700 soldiers were selected from Division 3700. Mr. Koppe asked whether this was correct. At this point, Mr. de Wilde interjected and said that there was an error in the English translation. It seemed like this referred to Division 3. Mr. Koppe said that this was not the case. “I see the witness nod, so maybe I can continue.” The witness clarified that there was no division 3700 in the East Zone. Instead, there were 700 soldiers in the East Zone.

The President put a clarifying question to Mr. Koppe: how would they divide the time? Mr. Koppe answered that Khieu Samphan team would ask questions once the Civil Party lawyers and Prosecution were done, while he himself would resume tomorrow.

The President thanked the parties. The hearing will continue tomorrow, January 26 2016, at 9 am.

[1] E1/370.1, just before 15.15.34 .

[2] Ibid., at 15:40.

[3] 20 January, at 14:04:04

[4] E3/7562, at 01170650-51 (EN) 00034056 (KH).

[5] D22/212, at 00418154 (KH), 00436795 (EN).

[6] E3/7809, at 00282563 (EN), 00271368 (KH), 00486103 (FR).

[7] E3/7809, 00282562 (EN), 00271367 (KH), 00486103 (FR).

[8] E3/7809. At 00282562 (EN), 00271367 (KH), 00486103 (FR).

[9] D22/212, at 00418154 795 (EN).

[10] E3/7562, at 01170704 (EN), 00034100 (KH).

[11] E3/7562, 01157781 (EN), 00034081 (KH).

[12] E3/6941, at 01165890 (EN), 00418325 (KH)

[13] E3/9352, at question 2.

[14] D22/212A, 01166071 (EN), 00584569 (KH).

[15] E3/7562, at 01157781 (EN), 00034081 (KH).

[16] 00034082-84 (KH).

[17] E1/37.1.1

[18] E3/9113, at 00974170 (EN), 00926353 (KH).

[19] E3/24, 00223581 (EN), 00204069 (KH), 00503921 (FR).

[20] Testimony of 30 July 2012.

[21] E319/23.3.54.

[22] E319/23.3.54, Answer 25.

[23] Answer 55.

[24] E3/9113, at 00974175 (EN), 00926358 (KH).

Featured Image: Civil Party Daung Oeun (courtesy: ECCC Flickr).