Internal and External Enemies of Democratic Kampuchea

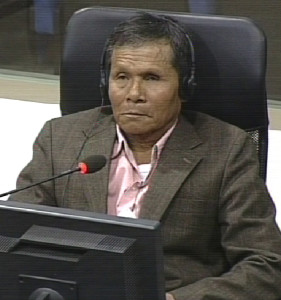

Today’s witness – Prum Sarat – was a former commander of a regiment and later of a vessel of the marine of Democratic Kampuchea. He gave evidence concerning the chain of command, figures of authority in his division as well as speeches held by Pol Pot and Khieu Samphan. He could not shed much light on the treatment of Vietnamese civilians since, he said, this was outside his responsibility.

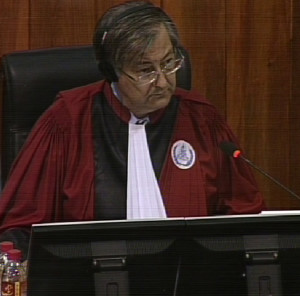

Health concerns: Khieu Samphan

Twenty minutes later than usual – at 09:20 – the Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn entered the court room. He announced that Khieu Samphan had heightened blood pressure and that his doctor had recommended to start the hearing an hour later, at 10.30 am.

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

When the Chamber resumed, the President announced that witness Prum Sarat would be heard. Witness 2-TCW-889 was on the reserve. The Trial Chamber then confirmed the presence of all parties with Nuon Chea following the proceedings from the holding cell.

The floor was then granted to Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe. Mr. Koppe referred to his Written Record of Interview, in which he had mentioned someone called Chhean, a former colleague of Division 164.[1] He replied that he was a former soldier and living close to the witness’s house in Samlaot. He was from the East Zone.

Mr. Koppe inquired whether Chhean was sent to the construction site at Kampong Chhnang airport. Mr. Sarat could remember this. Chhean had told him that he regretted not having had close contact to him in the period. Chhean did not tell him who went with him to Kampong Chhnang.

Mr. Koppe then moved to the territorial sea of Democratic Kampuchea. He asked whether he remembered what would happen in those years if boats came close to the islands or entered the territorial waters. The witness replied that the territorial water was based on the map of Cambodia, but he did not know exactly where it was. He did not know how far the Cambodian waters extended into the sea. Mr. Koppe repeated his question, but narrowed his question down to what would happen to Vietnamese people – refugees, fishermen, or soldiers – if they entered Cambodian territory. The witness replied that there was a hot battlefield at the time. Soldiers were arrested and placed on Koh Tral Island. The fighting ended later on.

When Vietnamese civilians enter the maritime territory

Mr. Koppe focused on Vietnamese refugees and fishermen and wanted to know what the instructions were on how to deal with these people. Mr. Sarat answered that fishing boats or other boats, which entered the territorial waters, “I could not tell you about the issue, since I was not stationed on the island itself”. He only gave training at Ou Chheu Teal Port.

This prompted Mr. Koppe to refer to Mr. Sarat’s DC-Cam statement, in which he had said that refugees and civilians were not arrested.[2] Mr. Koppe asked whether this refreshed the witness’s memory. Mr. Sarat replied that this was correct.

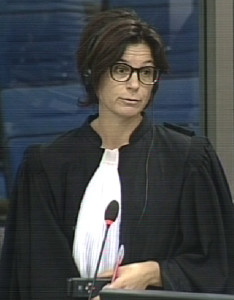

International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

Mr. Koppe referred to another person’s statement. This person had said that Son Sen had instructed them not to arrest Vietnamese refugees who were travelling to Thailand.[3] Mr. Sarat said that the instructions were from the upper echelon, but he was tasked with giving technical training. He did not receive instructions on these matters. When Mr. Koppe repeated the question, Mr. de Wilde interjected and said that the document had not been admitted into evidence yet. International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé said that the Khieu Samphan team had requested it to be tendered into evidence, a request which was granted on the 5th of January.

Mr. Koppe resumed his line of questioning and repeated his question. Mr. Sarat said that “based on this witness, it is true. I was a cadre in charge of ships. However, I was not responsible for the arrangement of foreigners crossing the territorial sea of Kampuchea. I was part of the training. Regarding the instructions and orders, they were under the command and responsibility of those who were stationed on the respective islands.” He had not received such instructions.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether Vietnamese soldiers would be arrested. Mr. Sarat recounted that there was on day where he encountered one Khlang and one Vietnamese person on Tang Island. He asked the soldier stationed on Tang Island where they were from. They were told that they were Vietnamese. He was told that they were crossing the southern part of the territorial waters and had been arrested the night before.

Mr. Koppe turned to a related topic and read out an excerpt from the same commander Hing Ret as before.[4] He had said that the “external enemies” referred to Vietnamese soldiers, and not Vietnamese fishermen. Mr. Koppe asked whether this was correct. Mr. Sarat said that this was true. There were conflicts at the borders between Cambodia and Vietnam between 1975 and 1977. During that time, the Vietnamese refugees were passing the territorial waters of Cambodia. They were not considered the enemy. Two groups were seen as enemies: first, the Vietnamese troops who were attacking and second the internal enemies, which were those who “instilled the contradictions within Kampuchea.”

Mr. Koppe read an excerpt of another witness’s statement, namely of the Division 1 West Zone Deputy Commander.[5] “They instructed us not to seek trouble with Vietnam.” The witness replied that this was the other witness’s statement. In general, he would agree to the statement that a small country did not have the power to attack a bigger country.

He recounted that a way of communication was the radio and the telephone. However, he did not witness the transactions where the people were sent. As for S-21, he said that “its purpose was to re-educate those whose living conditions were not in line with the standard. Or you could say those who did not follow the situations. And that’s what I knew that the office to re-educate cadres or to resolve other matters within the concerned unit.”

External and internal enemies

Mr. Koppe moved to his next topic and said that he had referred to the internal and external enemies. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether it was correct that the first enemy was Vietnam and the second one was the internal enemy. Mr. Koppe then asked what he remembered about the education classes chaired by Son Sen and what exactly was said about the internal and external enemies during these sessions. Mr. Sarat replied that it was about the “situation” in Democratic Kampuchea along the border. “There was no independence or peace along the border”, because of the fighting. Thus, the policy was that there were two categories of enemies for Democratic Kampuchea.

Mr. Koppe asked whether Commander Dim, the second in command, was considered an internal enemy. The witness replied that he was unable to say whether he was considered an internal enemy. He met him in 1975, but he disappeared in 1977, and he has not seen him since.

Mr. Koppe read out an excerpt of Commander Hing Ret again. This commander had explained the meaning of internal and external enemies and mentioned a Khmer Workers Party. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether this sounded familiar to the witness. The witness said that it was the commander’s personal account, but that he would agree to this. He confirmed that he had heard about the Khmer Workers Party and of the Indochina Federation, since Ho Chi Minh had plans to merge Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam into the Indochina Federation after the Geneva Conventions in 1949.

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

When Mr. Koppe referred to another document, International Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud said that this document had neither been proposed nor admitted to the Trial Chamber.[6] Mr. Koppe answered that they might have missed the deadline. Ms. Guiraud said that the document was on the interface, but not subject to an 87(4) motion. Mr. Koppe made the oral request to admit the document. The President asked the Co-Prosecutors for an option. Mr. de Wilde said that all parties would have to adhere to procedures and that this would result into “chaos” if everyone acted like this. Ms. Guiraud said that they never formally objected to the use of a document by the defense teams, but that they could have sent an e-mail beforehand. Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé said that this document was of exculpatory evidence and should therefore be admitted.

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne asked whether there were any other documents from this person, which Mr. Koppe confirmed, and whether there had been an 87(4) motion made for this other document, which Mr. Koppe denied.[7] He explained that they discovered the document after the 12 o’clock deadline.

After conferring with the bench, the President announced that the oral request by Mr. Koppe was rejected. He reminded the parties that the procedures had to be adhered to. The documents were too many pages to decide this at the moment.

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne

Mr. Koppe requested additional time to question the witness. When the Khieu Samphan Defense Team said that they would need half an hour, Mr. Koppe asked whether they could get an extension of the time of one full session. Mr. de Wilde said that they did not object to this extension, but would need more time as well.

The bench granted one additional session for each side: for the Defense Teams and for the Co-Prosecutors and the Lead Co-Lawyers. At this point, the Court adjourned the hearing for the lunch break.

Internal and external threats

After the break, the floor was granted again to the Defense Counsel for Nuon Chea. Mr. Koppe referred back to what Son Sen allegedly had said at the education sessions. Instead of the document he wanted to use before the break, Mr. Koppe referred to another document. This document comprised meeting of division secretaries and deputy secretaries of October 09 1976.[8] Mr. Koppe acknowledged that Mr. Sarat was never present there, but Meas Muth was.

It was indicated there that two enemies existed: one from the East and one from the West. Mr. Sarat recounted that Son Sen only talked about the organization of the army during the study session in Phnom Penh in 1976. Later, Son Sen had talked about the enemy, “who caused trouble to Democratic Kampuchea. And the enemy included two types: one was the external enemy and another one was the internal enemy. And he emphasized that if the external enemy caused trouble, there needed to be strategic fighting in the form of spying in Cambodia.”

Mr. Koppe asked whether there was a distinction between enemies to the East and enemies to the West. The witness replied that he remembered what he talked about “the West enemy”, which was about Thailand. Some of them came into the Cambodia. “They crossed the border to cut wood. They were not the strong enemy, because they could be defeated by our troops. Because those people were not experienced fighters. But he wanted us to be careful with the enemy from the East, because they could penetrate into Cambodia and could take the land along Cambodia.”

When Mr. Koppe read out an extract, which mentioned a Czech-Slovakian and Soviet style of attack, the witness recounted that “there were spy-agents who belonged to the Vietnamese and the Soviets. These were members of the so-called Warsaw-pact.”[9]

Mr. Koppe moved on and asked what the reasons could be for Commander Dim’s arrest. Mr. Sarat replied that the lower levels could not know much about the affairs of the upper echelon. Based on the “principle of secrecy, we were not informed, because the principle of secrecy means that only those who did it knew about it. So it meant I was not aware of the activities responsible by other people.”

Mr. Koppe asked whether he ever heard – even after the Khmer Rouge regime – if Dim was connected to Standing Committee Member Vorn Vet. Mr. Sarat replied that “the document from the court” was given to him “on the second night” and he “saw the list of people.” He had identified people.

Turning to his last question concerning the education sessions, Mr. Koppe inquired whether Son Sen ever spoke about coup d’états taking place in Phnom Penh to overthrow Pol Pot. The witness replied that he received this information during Son Sen’s lecture. However, he was not certain about how many people were involved. Mr. Koppe asked whether he heard about one, or four or five coup d’états that failed. Mr. Sarat replied that he could not remember how many coups there were planned at the time. Mr. Koppe then asked whether he remembered which number Son Sen used in telegrams. Mr. Sarat said that he could not remember well, “but at the time, I knew one number, which my higher-level authority told me that it was number 87”.

Mr. Koppe said that Son Sen seems to have been referred to as Brother 89, and asked who Number 87 was. Mr. Sarat said that telegram from Number 87 was from the upper echelon. He did not know whether this stemmed from a deputy secretary.

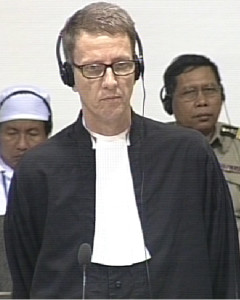

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Mr. Koppe turned to his next topic. He asked whether Mr. Sarat remembered saying something about difficulties of communication of Chinese radio equipment and American radio equipment that was used on land. Mr. Sarat confirmed this. It was difficult to communicate, since they used different techniques to communicate. The communication system employed by the headquarters in Kampong Som and the vessels were different to those used on vessels. Asked about communication from on-vessel to the land, he said that the communication was simple, since the Chinese communication system was compatible to the one in the headquarters. The combatants also received similar training in the headquarter. Mr. Koppe then inquired what would happen if Thai civilians, such as fishermen, entered the Cambodian territorial waters. Mr. Sarat said that he heard that the patrol boats were deployed, but could not be deployed to cover the entire territorial waters. These boats received a year of training. Then the soldiers on the islands would take actions, either “chase them away” or stop them from going further. “One day, I received information through the radio-communication, that a Thai fishing boat approached the territorial waters of Kampuchea.” There was an old American boat, Pi-110, and with this the Thai boat withdrew.

Mr. Koppe said that some Thai fisher boats were also stopped and the people arrested. He had said in an interview that the problems would subsequently be solved “diplomatically”. Mr. Koppe inquired what he meant with solving the problems diplomatically. Mr. de Wilde interjected and said the references would have to be given, which Mr. Koppe did.[10]

Mr. Koppe also referred to a newspaper report, which talked about an agreement of Thailand and Cambodia about Thai fishermen.[11]

The witness replied that the word diplomatic was based on the information he had heard. They had to deliver the people to the international section or department, so that the issue could be solved in line with the policy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. However, he did not hear about this in person, nor did he witness it being carried out. He could not shed light on an incident where Mr. Koppe said that all Thai fishermen had been liberated. Mr. de Wilde interjected and said that the questions were very generic, which is why the answer could only be generic. The President said that the Co-Prosecution’s time would come and Mr. Koppe could continue. Before handing the floor to the next party, Mr. Koppe reiterated that he made an oral request to admit the document under rule 87(4) so that this document could be used before next week’s witness.

In accordance with an agreement beforehand, the floor would be given first to the Co-Prosecution and lastly to the Khieu Samphan team.

Treatment of former Lon Nol soldiers

Mr. de Wilde started his line of questioning by turning back to the treatment of former Lon Nol soldiers.The witness had said yesterday that Lon Nol soldiers had been executed in 1975 or 1976.[12] He wanted to know what he heard regarding the executions of the Lon Nol officials. Mr. Sarat said that cadres said so in a meeting. He heard that they said that the Lon Nol soldiers were killed. “For example, while they were en route, they came across a location, where they saw two bodies.” He had not seen these dead bodies when he walked past the location.

Mr. de Wilde asked whether it was fair to say that Mr. Sarat did not know what happened to the Lon Nol officials and high ranking officers in Phnom Penh when he left the city on the 17 April 1975. “In fact, I never anticipated what happened next. […] We were on foot, and I never anticipated that there were high ranking Lon Nol soldiers or ordinary Lon Nol soldiers who were killed. My main task was to only lead my group of combatants and I did not receive such instructions.”

Mr. Koppe interjected and observed that he believed the witness had not actually referred to executions, but only to killings of Lon Nol soldiers in the course of fighting. Mr. de Wilde said that the Defense Counsel himself had used the word execution

Witness Prum Sarat

Mr. de Wilde then asked whether Meas Muth travelled to Koh Kong with his troops in the days that followed the fall of Phnom Penh. Mr. Saras said that he had not heard about this. “What I can remember is that he did not mention anything about the military officials or civil servants of the Lon Nol regime. In the meeting, he spoke about the task that we were assigned to do. As in my case and in my unit, we were tasked to prepare ourselves in order to be prepared to be equipped with the vessels that were given to us by the Chinese.”

Mr. de Wilde referred to witness Oeun’s statement, who had also testified in court on 07 May 2015.[13] Oeun had talked about the executions of Lon Nol soldiers on Koh Kong right after 17 April 1975 and mentioned Meas Muth. Mr. Saras said that his unit never received such information. He was not aware how this person came to know Meas Muth and what unit this person was attached to. As for Kampong Som, he recounted that he was “in my own barrack” and did not know “how to manage the town.” He needed a travel permit to enter the town.

Mr. de Wilde asked to confirm of June 1975 when Division 165 became a division of the center. The witness answered that it indeed took place in June 1975.

Training sessions

Mr. de Wilde asked whether he was transferred from the infantry to the navy around that time. Mr. Saras replied that he was detached from Division 3 in order to be with the Regiment 140 in June 1975.

Mr. de Wilde inquired whether he attended a technical training session as a commander of vessel 17/10, or whether he provided training. The witness clarified that he was not part of the crew initially. He was in charge of the training of the 38 members of Vessel 102. Vessel 17/10 was given to them at a later stage. He himself was not a trainer, but they received training from a Chinese instructor.

He had talked about training that was received by commanders and ended in 1976.[14] He denied having been the navigator of the vessel. He was the overall captain of the vessel. He did not go to China for the training, since they received training from Chinese instructors next at the port. The vessel under his supervision was a defensive vessel, according to the witness. Its main task was to patrol the territorial waters. Mr. de Wilde asked whether Koh Tral was close to Koh Russei and Koh Ta Khieu. He replied that there were two Koh Russei, one close to Koh Tral and another one.

Mr. Koppe turned to Division 164, which was headed by Meas Muth. He replied that Regiment 140 had two commanders: Saroeun and Sor from the East Zone. The commander of his battalion was Horn. They had all passed away. He could not recall Saroeun’s full name, but that his father’s name was Korn. Neither could he recall Horn’s full name. As for the number of soldiers in each battalion, he said that there were four battalions under each regiment, and four companies under each battalion. There were around 100 forces for each company.

Mr. de Wilde inquired about unit 450. He said that it was stationed around the divisional headquarters. He could not recall their specific tasks, but it was called the Special Unit for Division 3. The number remained unchanged. It was a combat unit for the “hot battlefield” in 1975. There were two other units that he was unsure about: 62 or 64. Three regiments were stationed on the islands: Koh Rung, Tang, Poul Loveay, Koh Thmey, and Koh Se Island. There were regiments 61, 62 and 63, but he was not sure whether Regiment 63 was stationed on Koh Thmey or Koh Se Island. At this point, the hearing was adjourned for a break.

Chain of Command

After the break, Mr. de Wilde resumed his line of questioning. He asked about the cadres. He recounted that there were four committee members at the headquarter: Meas Muth, Dim, Chhen and Nhann. They would issue orders, which went to Regiment 140. The orders also came from the division level to Unit 61, 62 and 63. The division issued orders to the regiment, which issued the orders to the battalion, which passed the orders to the company. Mr. de Wilde asked whether the reporting went the same way in the opposite direction, which Mr. Saras confirmed. “We needed to issue reports to the higher authority.” The orders had to be carried out. “We could not avoid it.” He further recounted that “everything was based on the order.”

Mr. de Wilde then asked about field orders and asked whether there were orders when they did not have to obey orders. Mr. Saras replied that they had to follow orders. Not following an order was only possible during special circumstances, for example when someone was sick or “really busy.” Thus “everyone needed to obey the order, no one could avoid it.” He did not answer the question what would happen to those who disobeyed the order. Mr. de Wilde asked whether there were sanctions, to which National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel objected on the basis that this would lead to speculation.

International Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde

The witness had talked about re-education in his Written Record of Interview.[15] Mr. de Wilde asked what it meant if someone was re-educated: were they sent to a security centre, or somewhere else? The witness replied that he was referring to “the offenders”, in particular “those who committed wrongs”. They were not sent to a location far away within his company, but it happened in other companies. He said that there were no cases of disobediences in his unit. “What I was doing at the time reflected what I was. I never implemented orders or regulations contrasting with the line.” Concerning the implementation of tactical strategies, for instance when a machine did not work, “this kind of issue needed to make a request to the battalion, regiment and division, after which there would be a reply, a response from the division.” They would then be able to repair the machine.

Meetings as speeches

Turning to his next topic, Mr. de Wilde asked about meeting that Mr. Saras attended in Phnom Penh. Mr. de Wilde wanted to know whether he travelled to Phnom Penh also for other occasions than for the meeting that was chaired by Son Sen. Mr. Saras did not give a clear answer to this.

Mr. Saras had said that he stayed in Phnom Penh in 1976 and 1977 and that he had saw Pol Pot giving a speech.[16] Mr Saras confirmed having gone there. “It may have happened in 1977.” He received the Revolutionary Flags on a monthly basis and had access to the radio broadcast on a daily basis.

Mr. de Wilde read an excerpt of a speech given by Pol Pot about the “Vietnamese enemy”. He had explained that one Cambodian had to fight thirty Vietnamese to win.[17] Mr. de Wilde pointed out that Pol Pot did not make any distinction between Vietnamese soldiers and Vietnamese civilians. He asked whether he heard Pol Pot saying that the Vietnamese enemies included Vietnamese civilians. Mr. Koppe objected and said that it was “very clear” from the rest of the Revolutionary Flag and also from an interview given to Elizabeth Becker in 1978 that he referred to troops and not civilians. The objection was overruled.

The witness said that there was a clear policy and “strict guidelines” for cadres to understand. “But I’d like to make a clear point that one of our soldiers needed to smash thirty Vietnamese soldiers who committed the aggression against the country.” This was, according to Mr. Saras, the guideline given in the Revolutionary Flag.

Mr. de Wilde inquired whether the number he had mentioned – 60 million people – was referring to soldiers only then. The witness replied that the “statement was meant to inspire Cambodian soldiers […] to attack and capture victory.”

In this document, it had also been referred to measures taken against Vietnamese people residing in Cambodia before the 17 April 1975.[18] Mr. de Wilde inquired whether he had heard officials mentioning this. Mr. Saras said that it was his understanding that “that was the political line and also the ideological standpoint. And it was meant to raise the spirit of the soldiers in the battlefield.”

He remembered that there was a deportation of Vietnamese in 1973. “Another deportation took place in 1975 or 1976”. Mr. de Wilde asked whether the Vietnamese who were not deported in 1973 or 1975 were subject to repressive measures. Mr. Saras said that he could not answer this, since it was “beyond the scope of my responsibility.” When the President instructed the witness to answer the question properly, Mr. Saras said that he was based at a different location.

Mr. de Wilde read out another extract of the same document and asked whether it was correct to say that the maritime borders as recognized by the Cambodians were not the same as recognized by the Vietnamese.[19] The witness replied that he was not aware of this matter. He recounted the incident of two persons on the island of Khlang and Vietnamese ethnicity. They were not certain whether the two persons were arrested in the territorial waters of Cambodia or Vietnam. Mr. de Wilde asked whether there were other examples of such an incident where it was unclear whether it was in the territorial waters of Cambodia that arrests were carried out. The witness replied that the information came to his vessel that he “needed to be careful”, because of boats that had entered that maritime territory. He did not know whether a person was of Indian ethnicity or not.

Speeches by Khieu Samphan

As for whether Khieu Samphan attended the meeting, Mr. Saras said that he did not. He could not remember having attended a speech by Khieu Samphan. Khieu Samphan delivered a speech through the radio every year, he recounted. “I never listened to his speech personally at any location. I only heard his speech through the radio.” Mr. de Wilde said that he had said in his Written Record of Interview, he had said that he saw Khieu Samphan delivered a speech.[20] The witness said that he could not give a clear answer who was who when he gave the interview.

Mr. de Wilde wanted to know whether Khieu Samphan spoke about the war with Vietnam in his speech that he heard over the radio. Mr. Saras said that he heard that Khieu Samphan made an announcement to be on alert in case the Vietnamese was invading Cambodia. According to the witness, it was a speech by him, who was a senior leader of the regime.

Mr. de Wilde then asked about the Mayaguez incident and inquired whether Khieu Samphan mentioned in his speech that the Americans had said that they got lost in the Cambodian territory. The witness replied that he did not say this at the time. However, “it was from a media that reported that the ship got lost into the Cambodian territorial water. So Khieu Samphan at that time said that the Americans had a lot of modern technology, so how come that the Americans said that their vessel got lost into Cambodian water territory?” At this point, the President adjourned the hearing. It will resume tomorrow at 9 am.

[1] Answer A166.

[2] E3/9113, at 0097206 and 0097222 (EN), 00926384 and 00926399(KH).

[3] E319/23.3.12, QA 75

[4] E319/23.3.12, at question and answer 70.

[5] E319/23.3.21, at question and answer 24.

[6] E319/23.3.17.1, at 01170833 (EN), 00996698 (FR), 00955619 (KH).

[7] E319/23.3.17, and E319/23.3.18.

[8] E3/13, at 00940342 (EN), 00652406 (FR) 00334975 (KH).

[9] At 00940343 (EN), 00334976 (FR) 00652406 (KH).

[10] E3/9113, at 00974221 (EN), 00926398 (KH).

[11] E3/2314, at 00165983 (EN), 00768209 (FR) 00722466-67 (KH).

[12] Testimony of Prum Sarat, 25.01.2016, at 15:41.

[13] E3/9582.

[14] E3/9113, on pp. 26-27, 00926361-62 and 00926365 (KH).

[15] E319/23.3.54, at question and answer 116.

[16] At 00926419 (KH).

[17] E3/4604, 00520344 (FR), 00519833-34 (EN), 00064713-14 (KH).

[18] At 00519836 (EN), 00064717 (KH).

[19] 00520351 (FR), 0051938-39 (EN), 00064720 (KH).

[20] At p. 91, 00926419 (KH).

Featured Image: Witness Prum Sarat (courtesy by ECCC: Flickr)