Day Two of the Appeal Hearings

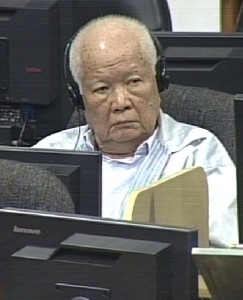

Today’s session, on February 17 2016, marked the second day of the resumed Appeal Hearings in Case 002/01. During the hearing, the Defense Team for Khieu Samphan submitted arguments to the Chamber relating to crimes the accused had been convicted for by the Trial Chamber and the modes of liability that had been applied. They claimed that the Chamber had erred both in law and in fact and wrongfully found Khieu Samphan guilty of these acts. The Co-Prosecutors reacted to these arguments and reasoned that the Trial Chamber had acted in an unbiased manner and that the proceedings had been fair.

The crimes for which the appellants were convicted

At the beginning of the session, the Supreme Court Chamber confirmed the presence of all parties with Nuon Chea following the proceedings from the holding cell and his international counsel being absent. The floor was given to Judge Florence Ndepele Mwachande Mumba to summarize the points of focus of the third section – the crimes for which the accused were convicted.

The two accused had challenged all crimes that they were convicted for:

- The Trial Chamber erred in relation to the so-called contextual element of crimes against humanity. They had to be linked to an armed conflict or a state policy. The existence of a discriminatory attack against a civilian attack had not been established, given that the only group that had been discriminated against were the Khmer Republic soldiers, who were not civilians.

- The foreseeability and modes of liability: Legal definition of crimes against humanity and murder, including whether it had been established beyond reasonable doubt that murder had been committed during evacuation phase 1 and at Tuol Po Chrey. They challenged that deaths occurred on a massive scale during Phase 1 and 2;

- New People could not be victims of persecution, since they were not part of a political group.

- Other inhumane acts: forced transfers and forced disappearances and attacks against human dignity. For forced transfers, it had not been analyzed whether it was an inhumane act under these circumstances. Forced transfers were not unlawful at the time according to the appeal. In addition, the evacuation was taken in light of security threats and food shortages. As for forced disappearances, these acts were not criminalized at the time of the acts and there was insufficient evidence that the enforced disappearances occurred during the population movements. As for attacks against human dignity, Nuon Chea submitted that the crimes he was convicted for were exaggerated.

International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

The floor was then granted to the Defense Team for Khieu Samphan. The biased approach by the Chamber did not reflect the facts. The partiality of the Chamber in the analysis of the crimes violated the rules of the trial. She said the facts and law had been manipulated. The benefit of the doubt had not been given to the accused. They had erred, Ms. Guissé submitted, in the criteria of the law that was applicable in 1975. In 1975, the chapeau elements of the crimes against humanity said that they had to be linked to armed conflict and committed as part of a state policy. She said that this was to be seen in belligerent conflict. She said that the Pre-Trial Chamber held the same view.[1] She referred to the Duch-Judgment, in which the Supreme Court Chamber had also said that there had to be a link. Law Nr. 10 of the Advisory Council: only applies to German territory. Moreover, the Tokyo Trials also retained the Nuremberg definition. The Flick Case also said that there had to be a nexus. She submitted that there was no uniform law at the time. Moreover, there was no nexus to war at the time. She said that the Prosecution had presented an “obscure decision” of the 15th century. She said that it was therefore wrong by the Chamber to decide that there did not have to be a nexus to armed conflict. Since the principle of in dubio pro reo existed, this should be fulfilled. The Prosecution had said that this principle only applied to facts and not to international law, which, she submitted, was wrong.

She referred to the Rome Statute. She asked why someone would use the Rome Statute to establish whether this criterion had existed in 1975 already.

She said that the law did not only state that there had to be a nexus to armed conflicts and a state policy, but also an attack towards the civilian population. The Supreme Court Chamber had asked whether this applied to hors combat soldiers. Ms. Guissé said that this only applied to an ongoing conflict, since soldiers could not be hors combat when there was no armed conflict. She argued that the Chamber did not set an alleged contradiction

She said that the deaths resulting from search missions were not civilians, since they were soldiers. If talking about after 17 April 1975, no armed conflict existed anymore.

She argued that the Chamber had lowered the threshold by saying that “accidental recklessness” was sufficient. Ms. Guissé said that there had to be intent.

Moreover, she submitted that there had been confusion by the Prosecution about actus reus and mens rea when interpreting Celibici. She moreover claimed that there was no recklessness by Khieu Samphan.

As for the definition of homicide and the intime conviction, she said that no characterization of murder was obtained by the OCIJ during population movement 2, which is why the Chamber relied on intime conviction. She said that the prior characterization of murder was necessary in order to talk about its “massive” nature later. There had to be a nexus between the crimes committed and the accused.

She said that the Chamber found that the people who were shot and who died because of the conditions were murdered

- Former leaders of the Khmer Republic

- Former soldiers

- Other people who resisted the forced movement

She said that the Chamber cited Al Rockoff who had said that he had heard by hearsay that Khmer Republic officials that they were killed, while there was no proper evidence for this. In contrast, other witnesses had said that there was no order to kill. Nor were there eyewitnesses for the executions at Tuol Po Chrey. Moreover, the Chamber had relied on factual evidence that were outside the case due to the severance order.

She said that this would lead to the violation of non bis in idem, since he would be convicted for the same acts in Case 002/01 and Case 002/02.

Ms. Guissé said that both the actus reus and mens rea had to be fulfilled in order to be able to convict someone of forced movements.

The expression “New People” itself was not accurate, since most people spoke about the 17 April People. This meant this took place after 17 April.

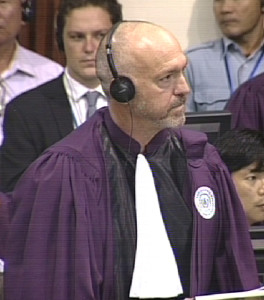

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian

The floor was granted to International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian, who first apologized to the audience for a technical account that was about to come before moving to his submission (after having been reminded by Judge Agnieszka Klonowiecka-Milart that he should speak to the judges and not the audience).

He referred to Article 6 of the Nuremberg Tribunal Statute. He said that it was important to look at the agreement in its totality. He said that the Statute showed that the limitation applied to persecution. However, it had been interpreted differently by the Nuremberg tribunal. He said that this criterion was inserted, because it was restricted to a specific geographic area to try one specific war. Hus, this was not to be viewed as customary international law. The Flick Case, Mr. Koumjian said, showed merely that they were trying to limit of cases. He said that Tadic Decision on the Defense Motion for Interlocutory Appeal on Jurisdiction (paragraph 140) also came to the conclusion that Council Law 10 had eliminated the criterion of a nexus to armed conflict. He then cited the case Kolk and Kislyiy v Estonia in front of the European Court of Human Rights (2006) that dealt with criminal acts of 1940s in Estonia and also set out that no armed conflict nexus had to be fulfilled. He said that another judgment had also said that the nexus had to be fulfilled for war crimes, but not for crimes against humanity.

Turning to the next question whether crimes that were committed against the soldiers hors de combat were still attacks against the civilian population, he said that he agreed with the defense team: the soldiers were to be considered civilians when the war was over.

Martic case: soldiers hors de combat could be victims of crimes against humanity, as long as all other criteria were fulfilled. He cited further case law to support this point. He concluded that soldiers hors de combat could be seen as crimes against humanity, as long as the chapeau elements were fulfilled and a link to the attack was established.

As for the last question, he said that the Chamber had established that a vast number of people had been killed, which could amount to extermination. He said that the same requirements an logic applied to extermination as for murder. The court had to be satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that murders occurred in an overall approach, but they did not have to proof each individual murder beyond a reasonable doubt. It had to be proven beyond a reasonable doubt that murders occurred.

The accused were all charged with all acts under a Joint Criminal Enterprise. All five policies were subject to litigation in Case 002/01. The Co-Prosecution had not understood that the Trial Chamber limited the Joint Criminal Enterprise. He said that he was under the impression that the defense teams had understood it in the same way. He alleged that both the mens rea and actus reus had been fulfilled.

Turning to his last topic, Mr. Koumjian said that Philip Short had said that Zone commanders had to act within the scope of policies. Thus, the Trial Chamber’s findings were fully supported on that point. All parties were able to ask questions outside the scope of the severance orders when relevant to the charges.

He said that a few documents that the defense teams had requested to be admitted allegedly showed the number of killed people. These were, in Mr. Koumjian’s view, irrelevant. At this point, the hearing was adjourned for a break.

Modes of Liablity

After the break, Agnieszka Klonowiecka-Milart asked whether individual murder had to be proven beyond a reasonable doubt in order for extermination to exist. The question would be answered tomorrow.

Ms. Guissé referred to Philip Short and said that “things changed from one place to another”. She said that Philip Short had said that there were difficulties to unify the military structure. The document that the Co-Prosecutors had used was only signed by 18 states and could therefore not seen as customary international law. She cited the Continental Shell Case and said that the criteria outlined there were not fulfilled. There was a problem of foreseeability and credibility that had not been resolved.

The floor was then given to the Co-Rapporteur to introduce the next section.

Juge Som Sereyvuth

He said that Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan had been found guilty under the first form of Joint Criminal Enterprise (JCE I) in relation to murder, persecution on political grounds, and forced movements. The Chamber held that extermination subsumed murder.

The grounds of appeal said that the chamber had set out that for JCE to be fulfilled a plurality of people had to share a common purpose. The participants had to act in a way to further the purpose. The Trial Chamber had determined that the common purpose was to further a rapid revolution with a “great leap forward”.

The Trial Chamber had distinguished between two kinds of participation by Nuon Chea: first by attending meetings and second by propaganda and education meetings. As for the intent, the Trial Chamber found that he intended to further the implementation of the common purpose. He shared the intent with the other participants of the JCE I, including discriminatory intent for political persecution.

They determined that Nuon Chea had intended to further the JCE, since

- He attended meetings of the standing committee and party congresses, where the plans were developed

- He attended meetings and sessions where lower cadres were informed of the policies

- He was involved in the economic matters, notably in the field of trade, export and import

- He encouraged the population to adhere to the plan

- He maintained diplomatic contact with the aim to gain support for Democratic Kampuchea

The arguments of appeal could be grouped as followed:

- Modes of iability had narrower criteria at the time

- The common purpose it identified was not criminal in itself. The Trial Chamber erred in determining that Lon Nol soldiers were targeted

- Challenges of the Trial Chamber findings for their sepcific powers in Democratic Kampuchea

The Defense Teams submitted that the actus reus was not established for the evacuation of Phnom Penh. This did not take place following orders by Nuon Chea, according to the Appeal. They raised errors in the findings regarding the structure of the CPK and said that the Chamber neglected positive conduct. At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Submissions by the Khieu Samphan Defense Team

After the lunch break, Ms. Guissé said that it was not possible for her to deal with all errors “in a comprehensive manner” during the 50 minutes that were allotted to her. They would focus on the errors in law today.

First, Khieu Samphan had not been able to envisage the modes of responsibility, since he only knew the dualist system in Cambodia. He was not in a position to envisage the Joint Criminal Enterprise. The Co-Prosecutors had said that the gravity of the crimes showed the criminal conduct of the appellant. However, she argued that the criminal conduct was a combination of both actus reus and mens rea, which made it impossible to look at only one of the categories. The elements of crime and modes of liability should have been foreseeable to fulfill the principle of legality. Ms. Guissé said that the Chamber erred fundamentally in the way it applied mens rea of JCE I. The Trial Chamber had said that there had to be a common purpose which could lead to the commission of a crime. Ms. Guissé did not agree with this approach. She said that the Tadic case presented the right definition, which was that a crime had to be committed as part of the common realization of the common purpose. Thus, the crime had to be intrinsic to the common purpose. By amending the applicability of mens rea, the Trial Chamber had lowered the bar according to Ms. Guissé. Thus, a person must have the intent of the implementation of the common purpose.

Supreme Court Chamber President Kong Srim

Turning to her next point, she said that an analogy had been drawn between conspiracy and JCE I. She cited the Nuremberg Trials and said that even in this framework of conspiracy, the standard of JCE had been defined in a similar way to Tadic, thus not any lower. She cited three other cases to support her argument (Einsatzgruppen Case, the Schoenfeld Case, and the Pohl Case). Comparing the situation to two other cases, she said that the analogy the Co-Prosecutors had drawn was not accurate, since these people were aware of what they were doing and that they were part of a JCE. The crime should be part of the purpose and not only a likely result. The Schoenfeld Case of June 1946, as quoted by the Co-Prosecutors, showed in her view that people had to come together to commit something illegal, and could be attributed to all persons present, since they knew they would be in a commission of that group. The question was, according to Ms. Guissé, whether the crime was direct or indirect. Creating a social regime in Democratic Kampuchea was not a criminal enterprise. As for a criminal part of the common purpose, Ms. Guissé said that the Chamber never showed Khieu Samphan’s involvement. She cited the Pohl and the Einsatzgruppen Case, in which she said the individual had to be connected to the purpose of the crime. As for whether Khieu Samphan was aware of such a common purpose and criminal enterprise, she queried whether Khieu Samphan could find documents to interpret “in an extensive way” the modes of liability, including the criterion of recklessness. That neither the Co-Investigating Judges, nor the Pre-Trial Chamber, nor the Co-Prosecutors, nor the Trial Chamber had raised this notion showed, according to Ms. Guissé, that “someone like Khieu Samphan could not possibly think about this”. The required element to determine the mens rea was the intent to commit a serious crime. In her view, the Trial Chamber never determined that Khieu Samphan intended the populations movements 1 and 2 and the crimes committed at Tuol Po Chrey. Holding him responsible within the framework of a JCE therefore lowered the standards.

As for the question by the bench on a recharacterization of the JCE, Ms. Guissé said that this would mean to introduce new constitutive elements that the Trial Chamber had not been called to rule upon. Moreover, this would aggravate Khieu Samphan’s fate, who had lodged the appeal and would therefore go against principles of international law. The Prosecutors had not appealed this point. She said that the Co-Prosecutors asked the Supreme Court Chamber to act in an illegal way in document F30/6. She referred to the Duch judgment to reiterate her position.

The same issue of lowering the mens rea threshold applied to the mode of liability of aiding and abetting, planning, and encouraging. As for aiding and abetting, Ms. Guissé said that this was based on international customary law. She said that this, in conjunction with the mischaracterization of facts, constituted the core problem of the judgment.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

The Co-Prosecution

After the break, the floor was given to the Co-Prosecution to respond to the arguments made. Mr. Koumjian said that Ms. Guissé had said that this would introduce a new element if the re-characterization of the mode of liability took place. He argued that she had not shown what new element would be introduced. It was in the lines of the Stakic Appeal Judgment. The Appeal Chamber had on its own changed a mode of liability without any party having challenged it previously. He said that he defense was correct, namely that the objective – or the means – that the people who entered the enterprise were contemplating the criminal nature. He said that the ultimate aim was not criminal, but the means were. As for Khieu Samphan, he had played an important part in the Khmer Rouge policy. The secrecy of the regime amplified his role, since he was seen by the public. He “was the person who was on the radio” who represented the Khmer Rouge when people were evacuated. “Khieu Samphan remained the voice” who was “justifying and glorifying” the acts of the Khmer Rouge.

He asked what the word intent mean and submitted that it always included “committing intentional conduct with knowledge” about consequences that will or might occur. He said that the person had to be aware that the conduct had to have a “substantial likelihood” to result in the crimes. He acknowledged that it had been defined differently, but said that the principles were always similar.

He referred to the Karacic case, in which evidence showed that the killings and forced transfers resulted in crimes. He argued that this case was similar. He said that conduct also included that “in a normal course of events” a substantive likelihood existed that the crimes existed.

Co-Appellant Khieu Samphan

He gave the floor to Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak. He attempted to show that “Khieu Samphan was not convicted because of some bias that the Trial Chamber held.” As for a meeting in mid-1974, Mr. Lysak said that Nuon Chea had testified on extensively. He referred to ICTR jurisprudence (case ICTR 98/44A/A) and said that this decision contained a detailed discussion of what is required from a Trial Chamber in this situation. The chamber had carefully assessed and accepted or rejected particular testimonies.

Phy Phuon said that he as a party member attended political education meetings and testified that the people who instructed him on the principles, policy and party lines, were Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary and Khieu Samphan. Phy Phuon was “different” to other cadres. “He was clear and straightforward. He was direct”. He was not evasive as other cadres. “He answered the questions. His memory was extremely good. He was a breath of fresh air in this courtroom.”

Moreover, the testimony of Khieu Samphan’s wife indicated that Khieu Samphan returned from China a month after she gave birth to their child, which would be in June 1974. There was a meeting in early April 1975 in B-5 that Phy Phuon had testified to. This office was set up by Pol Pot to plan evacuations. Phy Phuon had described “in detail” about the meetings and both Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were present, both agreeing that Phnom Penh should be evacuated.

Mr. Lysak then referred to a recording which indicated that Khieu Samphan was also present at another meeting.[2] The plan for the evacuation in itself was criminal, since this forced millions of people out of their homes without proper nutrition.

Mr. Lysak said that this was the evidence upon which Khieu Samphan was convicted upon: detailed testimonies and corroborative evidence. In his view it was, “by any account, a real and fair trial.” Mr. Lysak went through further evidence to show that the party leaders were aware of crimes.

He said that they simply did not have any evidence that “this was a show trial”.

Judge Agnieszka Klonowiecka-Milart

Judge Agnieszka Klonowiecka-Milart asked about the evacuation of Oudong and said that the same witness had characterized as having been conducted smoothly. Mr. Lysak said that when Phy Phuon had said that it went smoothly, he had meant that it was successful. Stephen Heder went there around a week after the evacuation and found murdered nuns and other people. He described this evacuation as “horrific” and stressed that “the same thing happened in every place when they captured it”. He would give more specific cites tomorrow.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing. It will resume tomorrow at 9 am.

[1] D427/1/30, paragraph 3

[2] E36/2346

Featured Image: Supreme Court Chamber Bench (ECCC: Flickr)