“Your Honors have My files and My Life in Your Hands” – Khieu Samphan Seeks Acquittal

Today, February 18 2016, was the last day of Appeal Hearings in Case 002/01. While the Nuon Chea Defense Team did not actively participate and relies on the appeal brief to argue for their case, the Khieu Samphan Defense Team sought acquittal of the accused or, if the Supreme Court Chamber should decide to convict the accused, limit the sentence to a fixed term and therefore reduce the life sentence that had been imposed on him in the Trial Chamber Judgment. Large part of today’s hearing dealt with the applicability of JCE I and III. At the end of the session, Khieu Samphan held a speech to address the Chamber. The Appeal Judgment is expected mid-2016.

Answers to the bench’s questions: Co-Prosecution

The Supreme Court Chamber Greffier confirmed the presence of all parties, with the exception of the international defense counsel for Nuon Chea. The co-appellant Nuon Chea followed the proceedings from the holding cell. The President announced that the Co-Prosecutors could make comments on the questions put forward by Judge Agnieszka Klonowiecka-Milart of the third thematic session.

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian first emphasized that there was sufficient evidence that the zone armies were under the control by the Center. He said that troops were taken to form a Central Army. He said that this showed clearly that there was a “hierarchical military force”. He said that an incident had to be proven beyond reasonable doubt when it had been charged individually. The Chamber did not convict them for murder in itself, since they had found this to be subsumed under the conviction of extermination.

He cited a few sources to show that a precise designation of numbers of deaths was not necessary to be determined. Instead, killing on a large scale had to be proven. The Chamber was not required to find on an individual basis that a murder had occurred beyond a reasonable doubt. The Chamber had to proof the killings on a massive scale beyond reasonable doubt in its totality.

Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak

He then gave the floor to Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak. Mr. Lysak referred to several testimonies that related to the killing of people during the first evacuation. First, he cited the testimony of Yim Sovann, who had been evacuated from Phnom Penh and who had described having witnessed a car that had run out of gas with people pushing it. The Khmer Rouge people took the driver out of the car and shot him. He had also witnessed the execution of people who had locked themselves into their houses, refusing to leave.[1] There were 48 accounts of people who described killings, 32 of which were eye-witnesses, of which 11 gave life testimony – the other were accounts obtained through Co-Investigating Judges documents, Civil Party applications and other sources.

Next, he referred to the testimony of Civil Party Chheng Eng Ly, who had witnessed a dead woman while crossing Monivong Bridge, whose baby was still on top of her.[2] This Civil Party described how the Khmer Rouge “tore the baby apart”.

Mr. Lysak then referred to the testimony of Pech Srey Phal.[3] This person had testified about the death of her baby during the evacuation of Phnom Penh. Mr. Lysak said that people were told that they left only for three days and therefore had insufficient food. The same person had also testified about the deaths of people who left the Russian Hospital in Phnom Penh.[4] Mr. Lysak argued that when forcing people to leave a hospital, “no matter how sick” and forcing them to walk without any assistance, “you know” that some of them would die.

Mr. Lysak further cited journalist Jon Svain, who had described the evacuations in his contemporary journal.[5] Mr. Lysak gave a few examples of top Lon Nol officials whose execution was proven: Long Boret (prime minister), Lon Non (brother of Lon Nol), Sirik Matak (deputy prime minister). There had been a broadcast on the radio station, in which Khieu Samphan had announced that these people were to be killed.[6] Mr. Lysak said that this clearly showed the intent to kill. “You cannot have stronger evidence than a broadcast on the radio”.

For Long Boret there was a radio broadcast calling for the Lon Nol officials to surrender at the ministry of information. Both Al Rockoff and Schanberg testified that there had been 50 prisoners, including Lon Non and several generals, who were gathered there.[7] They both had testified that they saw the arrests of Long Boret. Mr. Lysak said that this was not “revenge killing”, but organized acts, since the people were in close contact with the leadership through radio communication.

Judge Agnieszka Klonowiecka-Milart

Mr. Lysak further recounted the fate of Sirik Matak, who went to the French embassy together with 50 representatives of FURO (organization of ethnic minorities), but who was subsequently killed by the Khmer Rouge.[8] Moreover, Ieng Sary had announced in early November 1975 at a press conference that Lon Non had been killed.[9] Further, it had been said that leaders who remained in Democratic Kampuchea had been executed. Lastly, Nuon Chea had confirmed that the top Lon Nol officials had been executed.[10] At this point, Judge Klonowiecka-Milart interjected and asked whether the killing of officials was not part of Case 02, which Mr. Lysak firmly rejected.

Khieu Samphan Defense Team

Next, Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé said that she had talked about the nexus of Khieu Samphan himself to the decision to evacuation. She argued that the Chamber was “mixing up” two meetings in the judgments. The first was in June 1974, in which the witness had said that the evacuation of Phnom Penh was not discussed. She referred to a few people who had said that the meeting did not discuss the evacuation. Even if Khieu Samphan was present, no details had been provided about the discussion of evacuation.

Another witness had said the evacuation took place “because of the war”[11]. She cited another witness to support this argument. “So we have a problem here”.

Prince Norodom Sihanouk had referred to traitors, which was the context in which Khieu Samphan had delivered a speech (E3/120). She argued that the Prosecutors took this speech out of the context. “It is sad, it is terrible – during war people die”. She submitted that in war a goal was always to kill the opponent to achieve victory.

She said that the Chamber referred to insufficient evidence that Khieu Samphan was involved in the decision to evacuate Phnom Penh. She specified that no source had been given why the principle of in dubio pro reo did not apply then. As for the Martic case, she said that the Martic situation was different, since this took place in an armed conflict. She pledged: “of course terrible things happened during the evacuation”. However, it was “completely erroneous” in her view to speak about Khieu Samphan’s desire for this to happen. She said that the Co-Prosecution had not answered the question whether dolus eventualis existed in 1975. Moreover, even if the decision had been taken by the Standing Committee, she said that he was not even part of this. “This is the way that the Chamber manipulated law.”

Mr. Koumjian said that Ms. Guissé had answered points of the Prosecution, for which there was no scheduled time in the hearing. He requested to be able to react.

He said that the Chamber had explained in footnote 359 that the testimony of Ny Kan, the brother of Son Sen, was inconsistent and was therefore unreliable. He cited a Khmer saying, which said that the back foot followed the front foot, which he interpreted to mean that subordinates follow leaders. He said that Khieu Samphan had much influence and people followed him. He agreed with counsel that his speech had to be put into context – namely the brutality of the regime.

The President then announced that the next session would be introduced now.

Grounds of appeal related to the sentence

The Co-Rapporteur summarized that Khieu Samphan had argued that the accused should be at the center of the sentencing, and not the general public and deterrence. They argued that the Trial Chamber had not taken Khieu Samphan’s individual and mitigating circumstances into account. The Trial Chamber had failed to take into account his level of education and his “good character”. Khieu Samphan submitted that he was “trusted and respected”.

The floor was granted to Ms. Guissé. She said that it was not easy to plead on the quantum of sentencing when pleading for acquittal at the same time. “It is necessary to come up with subsidiary solutions”. She said that the Chamber had “sinned by favoring symbol over law.”

She said that the absence of individuasiation of sentence, the inclusion of aggravating circumstances, and omitting mitigating circumstances,

International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

She alleged that there was an error of discretion by the Chamber. It was about “dissuasion and punishment”. However, this did not mean that the sentenced person should not be “at the heart of the sanction”. The Trial Chamber had alleged that Khieu Samphan had a symbolic position and did not have any hierarchical power over others. She referred to the Nuremberg Trial case, in which the accused Funk was sentenced for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against peace.

She noted that the “rather faulty reason of the Prosecutors” told them that the gravity of the crime was aggravated by the circumstances. She argued that “the real question is the character of the accused.” The Chamber had cited aggravating circumstances due to the authority he had enjoyed. She said that the Chamber had never demonstrated which authority he enjoyed and how he had abused this power, while only abuse of authority was an aggravating circumstance.

As for the degree of education that the Chamber had used for an aggravating circumstance, the Chamber had not based itself on international law. She said that “all people who came to testify” in front of the Chamber talked about the human qualities of Khieu Samphan and the fact that they “never saw him say anything negative about anyone.” This should have been taken into account by the Trial Chamber. However, all errors lead her to plead for acquittal of Khieu Samphan and not only a reduction of the sentence.

Submissions by the Co-Prosecutors

National Co-Prosecutor Chea Leang

After the first break the floor was given to the Co-Prosecutors. National Co-Prosecutor Chea Leang said that the maximum sentence was life imprisonment and argued that it was the most appropriate for the accused. As held in Case 001 and 002/01 judgments, the primary factor was the gravity of the convicted person’s crimes. Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan had been convicted of crimes against humanity, extermination, encompassing murder, political persecution and other inhumane acts, comprising forced evacuation and enforced disappearances. The Trial Chamber found that at least 250 Lon Nol officials had been executed at Tuol Po Chrey and that the number of victims amounted to at least 2.430.000 during movement phases I and II. The gravity of crimes was aggravated by the fact that some of the victims were particularly vulnerable, such as children, elderly, sick people and pregnant women or women who had just given birth. Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were amongst the relatively small group of the people who were most responsible and were key actors in the formation of the policy. “the evidence amply shows that they knew the crimes would be committed and were involved” in committing them. Nuon Chea was deputy secretary of the party and standing member of the Central Committee, while Khieu Samphan was first a candidate member and then a full-rights member of the Central Committee. He “disseminated and endorsed the common policies”. He utilized his trusted character to facilitate the accomplishment of the crimes. Both Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan abused their authorities to accomplish the crimes. Both were highly educated and understood the conduct they were engaging in. Thus, there were no circumstances that could mitigate these matters. Nuon Chea had not challenged the sentencing, while Khieu Samphan had argued that the life sentencing was too high. He had not determined what sentence should be imposed instead. She said that Khieu Samphan had misrepresented the Trial Chamber’s findings. Despite the fact that he had limited authorities in some regards, he was the public representative and played an important role in bolstering the legitimacy of the movement.

He was a frequent attendee of the meetings, a leading member of the Office 870 and had other authorities. She submitted that Khieu Samphan had abused these authorities. He had aided, instigated and abetted the crimes. He had been a key actor in formulating the policies. His involvement was substantial, she said. The argument that he had limited authority was merely “evasive” about the role he played.

The Chamber had held that he was intelligent and well-educated. He could therefore fully grasp the nature of his acts and the conduct he engaged in. Moreover, the Chamber “rightfully found” that the “isolated circumstances” that someone testified that Khieu Samphan had a good character could not mitigate the gravity of the crimes. The aggravating circumstances neutralized any mitigating circumstances. Life imprisonment could also stand even if mitigating circumstances existed, if the circumstances were appropriate. Thus, the Supreme Court Chamber should no amend the sentencing of the Trial Chamber. The Chamber itself had set out that the party seeking reversal of the sentencing carried a burden to proof legitimacy of this claim. She submitted that the Trial Chamber had not committed any errors in this regard. “In any event, Khieu Samphan had failed to carry his burden” to demonstrate these errors. With this, she finished her submission.

Appeal by the Co-Prosecutors

The Co-Rapporteur said that the Co-Prosecutors had submitted that the Trial Chamber had failed to submit JCE III. The Supreme Court Chamber had the power to admit errors even if these did not have any effect on the sentencing. They had referred to Internal Rules and jurisprudence of the ad-hoc tribunals to support their position.

They had submitted that this form of liability was “firmly entrenched” in customary international law. They requested that JCE III was indeed applicable in these proceedings.

The floor was then granted to the Co-Prosecutors.

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian said that the appellants could also be held responsible under the extended category of JCE. The Stakic case showed that a perpetrator could be held responsible if 1) it was foreseeable that the crime might be perpetrated by a member of the group and 2) the accused willingly took that risk.

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian

The Tadic Appeal Judgment, he argued, set out in paragraph 220 that the criterion was the state of mind in which a person was aware that the actions of the group were most likely to lead to that result and willingly took that risk, even if not intending to commit the crimes – the dolus eventualis. Thus, JCE III held that when someone joined a group with a common purpose, taking the risk that co-members committed crimes within the jurisdiction of the court, this person should be held responsible.

An additional qualification could be added: the common purpose that was criminal had to increase the risk that the crime would be committed.

He asked whether it was not foreseeable that if you gave teenage soldiers opportunity to enslave people, the power to execute them and power over women, that these teenage soldiers might rape women? He said that this was absolutely the case, even if the official policy was not to rape women. The JCE members had “willingly taken that risk”.

The mens rea required that the crimes had to be foreseeable and that their contribution had to be substantial. This also applied even when the act itself was prohibited by the defendant or the perpetrator was not identified.

The law at the time was that you were held responsible when the crime was foreseeable, even if the crimes were unintended.

He said that the JCE III was part of the customary international law, despite what the Trial Chamber had said. The principle nullum crimen, sine lege only applied to the conduct and not the mode of liability. The common criterion of JCE III and JCE I and JCE II was that a person had the intent the commit a crime within the jurisdiction of the tribunal. They made an intentional and significant contribution to the criminal enterprise. He said that the person had made a culpable mens rea. Not to hold these perpetrators responsible for the crimes they foresaw and willingly took the risk for would amount to a violation of international law and not serve the purpose, namely to serve justice. At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Reply by the Khieu Samphan Defense Team

In the third session, the floor was granted to National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn. He argued that none of the arguments of the Co-Prosecutors in relation to JCE III could convince the Supreme Court Chamber that the Appeal was admissible. What they had just heard, he said, made their response to the Prosecutor’s Appeal even more convincing.[12] He addressed the Chamber on four different grounds to dismiss this appeal.

National Khieu Samphan Counsel Kong Sam Onn

The appeal was inadmissible, because

- the Prosecutors had no interest in litigation. They did not appeal the Trial Chamber’s judgment, but a decision that was issued at trial.[13] The Co-Prosecutors were not harmed by the judgment and could therefore not appeal;

- The Co-Prosecutors had not filed the appeal to the competent court. The Supreme Court Chamber was now seized of Case 002/01, while the appeal of the Co-Prosecutors was not based on the judgment of 002/01. He argued that the Co-Prosecutors had quoted the testimonies of other cases that did not belong to 002/01. For example, the Civil Party Ahmad Sofiyah had testified in Case 002/02;

- The Co-Prosecutors had waived the right to appeal and did therefore not have the standing to appeal the judgment. They did not file the appeal in accordance with the Internal Rules of the ECCC (74(2)). They had the right to file an appeal against a decision by the Co-Investigating Judges. The Co-Investigating Judges had issued a Closing Order, which stipulated about JCE I and II, and not JCE III. The Trial Chamber had removed JCE III, which was requested by the Co-Prosecutors. This decision was issued on August 20 2014. That decision was filed on 002/02. The decision stated that JCE III did not exist as customary international law before 1975. The Co-Prosecutors did not justify the need for intervention. The issue had been already tried twice: once before the Pre-Trial Chamber and once before the Trial Chamber. Thus, the appeal should be dismissed. It was not applicable under the principle of legality. The Co-Prosecutors had exaggerated, cited case law that was not relevant, and distorted evidence. He submitted that JCE III was not recognized under Cambodian and International Law between 1975 and 1979. It was created only after July 15 1999.

- The Co-Prosecutors had not proven that JCE III was foreseeable at the time of the crimes. It was impossible for the Co-Prosecutors to proof that JCE III existed before the alleged facts. JCE III was “absolutely not” foreseeable and assessable at the time.

As for the question posed by the Chamber of the definition of JCE III, he said that JCE III was not applicable. He said that foreseeability was not an objective element. It lay with the person and was therefore subjective. It had to be subjectively foreseeable. Foreseeability should therefore be established based on the accused. He referred the Chamber to case law to show that the general foreseeability was not sufficient either in fact or in law.[14] He reiterated that JCE III was only created at a later point and was therefore beyond the temporal jurisdiction of the Chamber. He therefore requested the Chamber to declare the Appeal inadmissible.

Questions by the bench

One of the judges asked counsel whether “foreseeable” or what was “foreseen” was the criterion. Mr. Sam Onn replied that the crime had to be assessable to the accused.

Judge Ya Narin asked counsel whether the accused should not be held responsible criminally at all, if the crimes were not foreseeable. Mr. Sam Onn said that the first point was about the inadmissibility of the Co-Prosecutors’ appeal.

Mr. Sam Onn then referred to an Appeal Judgment of the ICTY of 03 April 2007 (IT-99/36/A, document F30/11.1.17, paragraphs 365). He said that the language of this judgment was clear that the accused had to intend to participate or willingly took the risk to participate. Moreover, the crime had to be foreseeable.

Judge Klonowiecka-Milart interjected and said that counsel had “made [his] point clear”. She addressed the Co-Prosecutors and asked about modes of attribution of dolus eventualis and recklessness. She asked for elaboration on the part of the Co-Prosecutors that this was a general principle of law that JCE modes of responsibility could be used. Mr. Koumjian said that the conversation was made “more difficult”, since all lawyers came from different systems. He said that JCE included the dolus eventualis in which the accused could foresee the risk of members of the group committing crimes and reconciling with it, while recklessness simply did not meet the standards of care. He said that intent under JCE I also included a likelihood that the crime would occur. He said that “substantial likelihood” was the best phrasing. He said international law would profit from using consistent language. Dolus eventualis belonged to JCE III, while dolus directis belonged to JCE I in form 1 and 2.

Mr. Lysak then gave references with regards to the evacuation of Oudong. He referred to Heder’s statement, who went to Oudong the day after the evacuation.[15] Nou Mao had also talked about the evacuation of this city and testified that many people died.[16] Moreover, Philip Short had written in his book about the population being evacuated and that officials in uniforms were separated from the rest of the population and killed.[17] David Chandler had also researched on the evacuation of Oudong.[18]

Moreover, a speech held by Khieu Samphan on April 5 1974 also mentioned the evacuation of Oudong.[19]

He also cited a report by the US Embassy that referred to an open letter.[20] Furthermore, two cadres who worked at Khmer Rouge headquarter had testified. Kim Vuon, who worked at B-20, had said that these statements came from Khieu Samphan. Phy Phuon had said that the main task by Khieu Samphan was to “write”. He then directed the Chamber’s attention to an interview of Ieng Sary, who had said that Khieu Samphan was a de-facto member of the Central Committee before becoming a full-rights member.[21] To call Khieu Samphan a “symbolic leader” was not appropriate.

Ms. Guissé requested leave to respond to the points that had just been made and to JCE III.

She said that they had talked about Cambodian domestic law and set out that JCE was not part of Cambodian law at the time.[22] As for Short’s account, she said that the Defense Team had asked him about the sources. He had answered that he spoke with “a number of villagers” and at least one or two people spoke about Oudong.[23] Next, she said that Nou Mao had not seen the persons who were allegedly evacuated from Oudong.[24]

Furthermore, she said that another important point was that Democratic Kampuchea was based on the principle of secrecy. They had only two Standing Committee meetings when Khieu Samphan actually took the floor. What he said was limited to his functions and to information that he received. She further said that “never, never, never, had the Chamber been able to establish his role in criminal activity.” He himself had never said that he knew about the crimes committed.

Supreme Court Chamber President Kong Srim

The President then asked about the failure to summon Heng Samrin and wanted to know what remedy the Trial Chamber’s failure to do so, should the Supreme Court Chamber find that the Trial Chamber had erred. Ms. Guissé answered that she could not speak on Nuon Chea’s behalf, who had made the application to call him. She said that it was impossible to return to the Trial Chamber but that it was important to remedy an error.

Mr. Koumjian answered that it was in the Trial Chamber’s discretion not to call him. He said that it seemed like none of the evidence that was available from Heng Samrin seemed to be exonerating, but he would not object for the Supreme Court Chamber to draw conclusions in favor of the accused from the interview.

Ms. Guissé then said that she had forgotten to give references with regards to Oudong.[25] She referred to a document, which indicated that “we should not forget that […] people had to engage in propaganda” when being in war. As for Phy Phuon, she said it was not clear what he had seen being written.

The President said that Internal Rule 109 (5) gave the accused the right to address the Chamber for a maximum of ten minutes. Nuon Chea had waived his right, but Khieu Samphan sought to address the Chamber.

Khieu Samphan then delivered a 10-minute speech.

Speech by Khieu Samphan

Khieu Samphan

Good afternoon, Mr. President, and good afternoon your Honors. Good afternoon to everyone who is present, my sincere respect to venerable respect to monks residing in pagodas throughout the country. Dear my beloved countrymen. First of all, allow me to express my sincere thanks and gratitude to the Supreme Court Chamber for granting me the floor to express my opinions. I am confident that the Supreme Court Chamber is aware of the approach the Trial Chamber took in this trial, which led to my conviction to life imprisonment. The Trial Chamber had a pre-judgment of my guilt. With that determination, it sought and distorted evidence in order to confirm its prior decision. I have limited knowledge in legal and technical terms to submit to your Honors that the Trial Chamber distorted the evidence in my case. My lawyers have spoken better in this regard. What I want to say today, and what I want my countrymen to hear, is that as an intellectual, I have never wanted anything other than social justice for my country. At that point in time, I submitted a thorough proposal to reform the economy gradually in order to establish the foundation for economic independence for my country and to achieve a certain social equilibrium so there won’t be too large a gap between the poor and the rich. How could this be deduced that I wanted to see the killings of those men, women and children, or that I was a member of a JCE intending to kill the population?

Of course, in the 1960s, I wanted the economic reforms of the Sihanouk-Regime and I was against the policy of Lon Nol. However, I was also an independent intellectual with my own convictions. At the time, I believed in the Prince and that is why I came back into his government in the hope of making changes from within. With its independence and neutrality policy, he dared to refuse to be placed under the umbrella of the South East Asia Treaty organization defense, which is a military pact established by the United States of America through Southeast Asia, after the defeat of France at Dien Bien Phu. I thought that from this position of independence, the Prince would be able to adopt my proposal for a necessary reform to lead the basis for economic independence for the country and make it able to do without foreign aids, especially the US. But I realized that it was merely an illusion. I noted that in fact, he practiced a double-faced policy. He held other hand to the socialist countries, but on the other he allowed Lon Nol to lead repression against progressive and patriotic forces. And that’s how I was forced to flee into the forest.

In the context of the facts of the time marked by the struggle for independence of colonial people and the Cold War, while I was in the jungle, I saw the CPK leaders who demonstrated their patriotism in their fight against Lon Nol and the United States by relying on their own, independent self-mastery and self-reliant forces. I was convinced that after the war, they would be able to cope with the huge challenges of reconstructing the economies, the livelihood od the entire population while defending its national independence and sovereignty which was hard won with the greatest sacrifices of the people and nation to define the so-called policy of the communist party of Kampuchea, the Trial Chamber followed the same approach as that of the CIJ and Co-Prosecutors. They only looked at what happened in the basis. They failed to find out if such implementation at the local level consistent with the original objectives and directions that were established. This is a fundamental issue for me. I shall shout loudly that I never wanted to agree to any policy that is against the Cambodian people. I’ve never have wanted a policy that involves crimes against the population, as alleged by the Trial Chamber. What I heard during the court hearings, and what I have read during my many years of detention confirms my belief that the revolutionary ideology which I believed, was misguided by people who clung to their power of feudal laws. They were the people who wanted to retain their privileges and were concerned about their interests and did not understand that it was their duty to make every effort for the welfare of the population. Throughout the investigations and trial, the co-investigating judges, the Co-Prosecutors and the Trial Chamber all alleged that I had the power in the decision-making process. In reality, I was never given such right. This is a distortion of fact. In reality, it is the opposite. Today, your Honors have my files and my life in your hands.

I do not have any more hope for the Trial Chamber, as they even wanted to prevent me from working on my appeal briefs. And your Honors have the appeal brief by me and my lawyers. I asked you to please examine the evidence objectively with an open mind and without any prejudice, even though I know that they want to make my case a symbol of condemnation. I cannot find words to alleviate the suffering of the Cambodian people. All I can say is that I never had the intention to commit crimes or contributed to the commission of crimes during the evacuation of Phnom Penh, the event at Tuol Po Chrey, or in the context of what the Trial Chamber called the second phase of forced movement of the population. I never wanted any crimes committed against the population, nor participated in any plan to do what at any time during the period of Democratic Kampuchea regime. And that is what I would like your Honors to keep in mind when you make your decision in this case. Thank you your Honors.

The President announced that this concluded the appeal hearings. He thanked the parties for their submissions, security personnel, greffiers and everyone else who had contributed to the hearings. Once the deliberations were concluded and the judgment drafted, the Judgment would be pronounced in open court. A scheduling order for this hearing would be issued in due course.

The next Trial Chamber hearing will take place on Tuesday, February 23 2016, at 9 am.

[1] Testimony of Yim Sovann, 19 October 2012, at 14:16 and 14:20-14:27

[2] Testimony of Civil Party Chheng Eng Ly, 29 May 2013, at 15:32-34.

[3] Testimony of Pech Srey Phal, 5 December 2012; E1/148.1. at 10:01-10:06.

[4] Ibid., at 09:51-09:53

[5] E3/51, at S0003279 (EN), S00644713 (KH), 00597837-38 (FR).

[6] E3/1117.

[7] 28 January 2013, E1/65.1, 11:29-11:57; Schanberg: June 5 2013, at 10:50-11:02

[8] E3/2694; E3/2702; E3/2710; E3/2706.

[9] See E3/604 and E3/608.

[10] E3/4001R, “One Day at Puol Chrey”, at 22:07-22:11.

[11] 20 May 2012, at 10:21.

[12] F11/1.

[13] E313/3/1

[14] 03 April 2007, ICTY Appeal Chamber.

[15] Testimony by Stephen Heder, at 14:33 and 15:12-15:14.

[16] 19 June 2013, at 09:20 and 11:31-11:33.

[17] May 07 2013, at 13:34-13:38.

[18] E3/1593, “The Pol Pot Regime”.

[19] E3/167.

[20] E3/195.

[21] E3/573.

[22] F11/1, paragraph 75

[23] E1/903, after 13:37, May 27 2013.

[24] E1/2091, shortly before 11:36.

[25] E3/195, at 00412706 (EN).

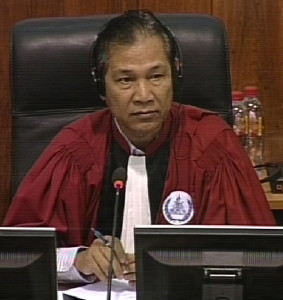

Featured Image: Khieu Samphan at the Appeal Hearings (ECCC: Flickr)