Macro-Level Factors and Localization: Expert Gives Evidence on Mass Killings

Today, March 14, 2016, expert Alexander Hinton (2-TCE-88) gave the Chamber insight about the dynamics of mass killings. He asserted that mass killings and violence occur when specific macro-level denominators are fulfilled and adapted to the local context. The macro-level indicator includes socioeconomic upheaval, structural divisions and change, the existence of a target group, an ideology that could attract people and the annihilation of moral restrain.

As for the local factors, his testimony focused on the cultural notion of disproportionate revenge and the culture of patronage and power. He explained how manufacturing differences between one group and “the enemy” was crucial to incite and justify killings of the latter group. He also stressed how targeted groups were de-humanized to overcome internal inhibition to kill them.

Background of the expert

The Trial Chamber Greffier confirmed the presence of all parties with Nuon Chea following the proceedings from the holding cell. Expert 2-TCE-88 would be heard today.[1] The Chamber then issued an oral ruling to admit E319/23.4.1. President Nil Nonn ordered to usher in the expert.

Alexander Hinton was born on October 16, 1963 in the United States and is a US citizen. He currently resides in New Jersey in the United States.

The President then announced that Professor Hinton had taken an oath according to the Buddhist religion in front of the iron club statue. He had indicated his wish to be sworn in in front of the Chamber, which was done.

Professor Hinton is an anthropologist and a professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He resided in Cambodia from 1994 to 1995 as a graduate student and conducted his research for the book called Why Did They Kill?. Since then he has continued to do research, but on other topics. His focus originated from why Khmer people killed Khmer people. As an anthropologist, his concerns were also focused on what people experienced and not only on the historical account or the political institutions. He conducted a comparative research on genocide, using several examples.

He first came to Cambodia in 1992, then returned in 1994 and stayed until 1995. His next trip to Cambodia was in 2000, then 2003. In 2009 (during the Duch trial) he visited Cambodia more frequently, staying for two weeks each time. The last time he came was approximately a year ago. He conducted his research in Khmer after having received language training prior to his arrival in 1994. Since his initial training was as a psychological anthropologist, his initial concerns in 1992 were more focused on Cambodian conceptions of psychology, such as the consequences of trauma and display of emotions.

Mr. Hinton then described an incident that particularly shaped his interest in mass killings in Cambodia. The lights would go out frequently in Phnom Penh. The father in the family with whom he lived would talk about his experiences under the Democratic Kampuchea regime while it was dark.

The President then wanted to know when he started writing his book. He said he returned to his university in 1995 and began the writing process then. The first draft was completed in 1997. He focused on two main questions:

- how genocide comes to happen

- what motivates someone to kill another human being

He then explained anthropologist methods. He told the Court that anthropologists live in a community, so he lived in Kampong Cham city and commuted by moped to a city near Phnom Phrol, Phnom Sray. He said that if he remembered correctly, there were 12,000 people said to be killed there and mass graves in the village.

Anthropologists often, he said, relied on multi-site ethnology, which is why he also undertook archival research in Phnom Penh. He also conducted interviews under human subjects protection.

Another method was participant observation, which was a more open approach without specific questions and relied heavily on observing the social settings. Moreover, he conducted in-depth interviews with key informants and a brief survey in Banyan about the current professions of the people there.

The President then inquired about the reasons for the title. He answered that he selected that title, because it was the question that was the concern of the book and because this was the question that Cambodians had asked “many many times”.

The floor was then handed to the Co-Prosecutors. Deputy Co-Prosecutor William Smith thanked Professor Hinton for his time and then wanted to know whether it also included a thesis why Khmer people killed Vietnamese or Cham, since he had said that the main question was why Khmer people killed Khmer. Professor Hinton said that the question was linked to his understanding of genocide and why he chose that word. For much of the historical detail, he relied on other scholars such as Ben Kiernan and David Chandler.

Within genocide studies, people had proposed different definitions than the legal definition that was used by the court. He used the broader definition of the intent to kill “because of who they are”.

Discussion about scope of questions

When he elaborated further, Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe interjected and said that the expert should refrain from talking about the definition of genocide. He said he asked for guidelines how to deal with this “very contentious legal debate”.

Mr. Smith replied that he did not intent to discuss the definition of genocide. Mr. Smith wanted to know whether it was fair to say that the book had dealt with the question why there had been mass killings of various groups. Professor Hinton answered that this was correct. He was also a scholar of genocide studies. He noted that the legal definition had also ambiguities. He clarified that it was important to understand his broader understanding of genocide to understand why he used this term in his book, since doing otherwise would misrepresent his research.

Mr. Koppe interjected again and said that the Chamber should instruct the expert to either use it in his broader definition, the legal definition or refrain from using it at all. Mr. Smith said that it seemed reasonable to use the broader understanding but to refrain from using that term in particular. Mr. Koppe said that expert Philip Short was stopped “almost immediately” from using the word genocide. Judge Claudia Fenz said that they should refrain from using the term genocide and concentrate on factual discussions. If the issue came up when referring to his book in particular, this would have to be treated with on a question-to-question basis.

Areas of expertise

Mr. Smith said that the Chamber had instructed the parties to focus on the treatment of Vietnamese and Buddhists. He said that his questions were divided into three parts:

- Professor Hinton’s experiences, particularly in genocide studies

- Why individuals killed individuals in Cambodia that belonged to specific groups and local customs or local norms that played a role in this

- example of the treatment of the Vietnamese

Turning to his first point, Mr. Lysak asked whether it was correct that he was the head of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. Professor Hinton corrected this and said that he was the director of the Rutgers Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights. He also held the UNESCO chair in genocide prevention. His degree from Western University was in social science. He received his PhD and master’s degree in anthropology. His dissertation was the first version of what would later become his book Why did They Kill.

Next, Mr. Smith wanted to know whether the areas of specialization mentioned in his CV were correct.[2] He said that it was and clarified that peace and conflict studies could be added. He guessed that this CV was around two or three years old.

When he began his doctoral studies, he had not been aware of the field of genocide studies. He joined the International Association of Genocide Scholars in around 1996, and eventually became president of this association. Mr. Smith wanted to know what the focus and goal of the International Association of Genocide Scholars was. He answered that their aim was to support scholars to undertake scholarly research. They also welcomed other practitioners and graduate students. There are only a few anthropologists in this association and more political scientists and historians.

Mr. Smith inquired whether what he called the genocidal studies was a field on its own. He answered this in the affirmative, since there were journals and studies focused on this issue only. It was an interdisciplinary field, so scholars also drew on experiences of other disciplines while being still shaped by their own background.

As for the UNESCO chair in genocide prevention, he explained that it was a scholarly chair and not an activist chair.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Studies

After the break, the floor was given back to the Co-Prosecutors. Mr. Smith asked whether he had been the sole author of any other book than Why Did They Kill. The expert explained that he was currently in the process of finalizing Man or Monster, which will be published in October. The focus of this book is the Duch trial. He was co-author of seven or eight books. They all dealt with mass violence and genocide, with the exception of Bio-Cultural Approaches to the Emotions.

Mr. Smith wanted to know whether it was correct he had published 48 articles, had been invited to 90 lectures, and held 32 honors, awards and fellowships. The expert said that he did not count them, but that he assumed that this was correct.

He received an award as one of 50 key thinkers of genocide. He explained that there were two editors who selected fifty key thinkers, amongst who he was. He also attended around 80 professional meetings in relation to issues about political violence and mass killings. He explained that this included giving workshops, participating in workshops, being key note speaker, and others. Many of these were interdisciplinary. His focus on this area commenced around the time that he conducted the research for his book, so around 20 years ago.

Mr. Smith inquired whether he had looked at the role of propaganda in the occurrence of mass killings in the comparative studies.

Deputy Co-Prosecutor William Smith

Mr. Smith asked him to list all boards and chairs that he is on in relation to mass violence and genocide studies.[3] He replied that there was a cluster relating to journals, another cluster relating to genocidal studies, another one to book series, and that he was an academic adviser to DC-Cam. He elaborated that he had done research on Tuol Sleng with the help of DC-Cam. He had done research by conducting interviews on Banyan village, including a few Khmer Rouge cadres.

When Mr. Smith asked about the openness of cadres to speak about their experiences, Professor Hinton said that people spoke more wearily in 1994 and 1995, whereas they now spoke about it more freely. He explained that they would tell him most if not directly ask what they did certain things, but more asking about contextual elements and reasons for other people’s acts.

He had a research assistant who did not speak English who would help when the interviewees did not understand his accent.

Macro-factors leading to mass violence

Moving to part two of the questions, Mr. Smith said that he had said that there were common universal macro-factors that often occurred when mass killings occurred in countries. These factors, according to the book, needed to be localized and linked more to the culture of the particular country in order to make people kill. Mr. Smith wanted him to describe and summarize the thesis of his book more clearly.

Professor Hinton said that he developed a model that was more of a cluster of genocide that fell under ideological genocide. He drew a parallel to Rwanda and Nazi Germany. He looked at a series of primes. One factor that was almost always present was socio-economic upheaval. This included the conflict in Vietnam, the US bombing and the coup that took place. Within that context, a group of people would offer a vision that seemed appealing, since people tend to gravitate to messages that were simple in times of existential angst. People would gravitate to that blueprint that pictured a solution.

When Professor Hinton elaborated more on genocide and genocidal regime, Mr. Koppe interjected. He agreed that the word could not always be avoided. However, he argued that “his client downstairs” was quite upset and wanted to come upstairs from the holding cell. Mr. Koppe said that the expert should use the word only when absolutely necessary. Mr. Smith asked the expert to avoid the word genocide unless absolutely necessary and instead stick to the word mass killings.

Professor Hinton said that it was difficult not to use the word genocide when using the model of genocidal priming. He said that not to use this was basically self-censorship. Mr. Smith said that it was acceptable to use it in relation to comparative studies, but not in the context of Cambodia.

Mr. Smith referred to his book and quoted the factors he identified as often being present during genocide.[4]

While each genocide has a distinct etiology that resists reduction to a uniform pattern, many are broadly characterized by a set of primes that make the social context in question increasingly “hot,” including socioeconomic upheaval, deep structural divisions and an identifiable target group, structural change, effective ideological manipulation, a breakdown in moral restraints, discriminatory political changes, and an apathetic response from the international community. As these and other facilitating processes unfold, genocide becomes increasingly possible.

Mr. Smith wanted to know whether it was his thesis that these factors often occurred in countries in which mass killings occurred, which the expert confirmed. Mr. Smith wanted to know whether these factors contributed to the treatment of different groups that he stated were killed during this period. He confirmed this and said that all of them were present.

Mr. Smith then referred to another passage of his book, in which he said that these factors were not enough to activate mass killings, but that they needed to be localized in order for any person to carry out the mass killings.[5] Professor Hinton confirmed this and said that he referred to ideological localization and take.

He gave the example of existing structural divisions between the rural and urban population. Marxist-Leninist ideology was taken to talk about a class “grudge” along these lines. If the broad ideology was not localized, he argued, people would not be motivated to follow. He clarified that culture caused violence, but that all violence needed to be reflected in cultural resonance.

Mr. Smith referred to social and economic upheaval that Professor Hinton had mentioned earlier and asked whether it was correct that these contributed to the attraction of people toward ideologies. He explained that people had existential angst in these times and would gravitate to a blueprint of a better world. Mr. Smith wanted to know what ideologies were more attractive during this time. He replied that people were often making macro-level planning. The local divisions on the ground often did not match up with the macro-level. The implementation did not match with the ideological outline. This led to problems such as problems with agriculture during Democratic Kampuchea. He gave the example of Ieng Tirith visiting the Northwest Zone and speaking about bad living conditions. Under Democratic Kampuchea, there seemed to have been an attempt to stick with the blueprint and not revise the blueprint.

Mr. Koppe said that the expert should not be allowed to make such far-reaching conclusions about events that took place at the time. Mr. Koppe said that the expert was going beyond his expertise when interpreting these events. The expert should confine himself to what he could say from an anthropological perspective and not interpret the events.

Mr. Smith said that an expert could give opinions and facts. He had written a book on the situation in Democratic Kampuchea. As soon as the expert gave answers that were too long and less relevant, Mr. Smith would ask questions to reset the focus.

Mr. Smith then resumed his questioning and wanted to know whether the CPK were putting forward a blueprint that was attractive to the people during Democratic Kampuchea. Mr. Koppe objected to this question and said that this went beyond Professor Hinton’s expertise and said that he was neither a political scientist nor a historian. Neither was he an expert on the political structure of CPK and their ideology. Mr. Smith disagreed and said that he had elaborated at length why people were attracted to the ideology in question. He had not asked about the political structure of the CPK but about the ideological blueprint. After briefly conferring with the bench, the President gave the floor to Judge Claudia Fenz to make an oral ruling.

Judge Fenz announced that the objection was overruled. Different areas overlapped and this could not be avoided. Being professional judges, they were able to judge where the expert overstepped his expertise and where he did not. She then instructed the expert to keep his sentences short and to avoid words in German or Latin.

Mr. Smith asked what the blueprint, or the high-modernist simplistic plan, goal or program, of CPK was. He replied that there were several layers. As for the attraction to the masses, the leaders had focused on land and wealth issues and worked this into class oppression issues to create a class grudge. Mr. Smith inquired whether this appealed to a specific group of Cambodian. Professor Hinton confirmed that it appealed to young and poor people. In terms of socio-economic structural divisions, they were the ones who experiences distress and were attracted to a vision that gave them hope and promised them to raise in status. They were the ones who gravitated most to this security “that we all seek”. To refocus the discussion, Mr. Smith referred to Professor Hinton’s book and read a quote about manufacturing difference.[6]

Genocidal regimes construct essentialized categories of identity and belonging, a process I refer to as “manufacturing difference.” Difference is manufactured as genocidal regimes construct, essentialize, and propagate sociopolitical categories of difference, crystallizing what are normally more fluid forms of identity (the “crystallization of difference”); stigmatize victim groups in accordance with the differences that being crystallized (the “marking of difference”); initiate a series of institutional, legal, social and political changes that transform the conditions under which the targeted victim groups live (the “organization of difference”); and inscribe difference on the bodies of the victims (the “bodily inscription of difference”)

There was a brief interruption, since there was no French translation. Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne instructed the Deputy Co-Prosecutor to put shorter questions to the expert. Mr. Smith asked whether identifying target groups was a key factors to contribute to mass killings, which the witness confirmed. The crystallization of differences referred to the fact that “we all” experienced differences of “us and them”. When one group was blamed, as for example Muslims in the United States, and this differences were made aware of and stressed, this might lead to conflict in times of upheaval. He compared this situation to the one of the Vietnamese minority under the Khmer Rouge regime.

Mr. Smith inquired what the process of marking differences or stigmatizing differences entailed. He answered that different values were stressed that led to the dehumanization of groups of people.

The group that was being stigmatized was marked as being a threat. The regime in question would construct political re-structuring and controlling them, such as keeping records and displacing them to different areas. Regulating and controlling them increased the likelihood of mass violence.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for lunch break.

Identification, stigmatization and discrimination of targeted groups

After the break, the Chamber requested the expert to use simple terms and speak slowly. The floor was then given to the Co-Prosecutors. Mr. Smith said that he had one last question in the second segment of questions. He inquired why generally the creation of identifiable target group in a society made it easier for a would-be perpetrator to kill. Professor Hinton replied that the target group represented a scapegoat.

Mr. Smith said that Mr. Hinton had talked about a three-way process: first, the perpetrators identified them, then stigmatized them and then conducted restricting including the restricting of laws and institutions to fit this stigmatization. These institutions helped them discriminating them and distinguishing them from others.

Mr. Smith wanted to know why this institutionalization of difference made it easier for a would-be perpetrator to kill. Professor Hinton replied that a regime would create a range of methods to identify people. This could range from security systems to surveillance systems. This helped would-be perpetrators to kill. He said that an example was the holocaust. A difference needed to be made between intentionalist and structuralist: was the intent already there in the beginning to, for example, kill the Jews? Mr. Smith repeated his question and referred to the status of the victim and the perpetrator. Professor Hinton replied that it was easier to target the group if you had control over them and they were not dispersed. As for the language of de-humanization and the attributes alleged to them, he replied that this might entail bodily transformation of the victims. He gave the example of Jews having lice due to the living conditions they were held int. This, he said, made them “look like the very thing that the ideology asserts that they are”. He further confirmed that this made it easier for the perpetrator to kill. The stigmatization and organization went along, since they were both stigmatized and at the same time controlled to make them fit these categories.

The policy of the CPK

Moving to the last segment of the questions, Mr. Smith asked whether the CPK leadership manufactured differences. He replied that it was “everywhere you turn” in their radio broadcasts and publications. The identifiable target groups might change over time, Professor Hinton alleged: in the beginning, Lon Nol officials were targeted and some groups. On September 30 1976, Professor Hinton said that there was a shift to internal enemies. In 1978, there was another shift with people being described as Vietnamese spies, Vietnamese lackeys or Vietnamese prisoners of war. This was not a clear-cut development, but a general development. There was a class-grudge to reinforce the “we” vs. “them” image. Mr. Smith wanted to know whether the targeted groups also included people form the cities. Professor Hinton said that “of course the cities were associated with capitalism, with capitalism […] with feudalism”. The people from the cities had fought against the Khmer Rouge, which was why they were seen as having traits and elements specific to the New People/17 April People. Some of these traits were later seen as not being able to be changed.

Mr. Smith wanted to know more about the Security Center called Phnom Pros near what he called the Banyan village. Professor Hinton said that the area was associated to Koy Thuon and his associate Sreng and the purges. There were also people being brought in from the East Zone who were killed there. People talked in particular about New People, students, ethnic Vietnamese, Cham people and Lon Nol officials who were killed there. It was in operation from at least the time that the Southwest Zone people came in. The villagers were not allowed to go there from 1975 onwards.

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

When Mr. Smith asked whether the Lon Nol officials were also a targeted group under the Khmer Rouge regime, Mr. Koppe interjected and said that he found the evidence offered by the expert problematic. He was offering factual evidence regarding security centers and targeted groups. He said the sources for this knowledge were not clear. It was only up to the Trial Chamber to assess this evidence. The purpose of this expert was not to offer factual evidence regarding issues that were contentious. Mr. Smith replied that the expert was a unique expert in the sense of having spoken first-hand to victims and cadres and also giving evidence with regards to original documentation from the CPK. These two sources of knowledge, Mr. Smith alleged, the expert was well-qualified to give his opinion on these matters as they lay within his area of expertise. The defense could cross-examine the expert later. Mr. Koppe said that the expert should provide the sources and indicate who he talked to and their rank. The bench briefly conferred and decided that the last question to the expert by the Deputy Co-Prosecutor was allowed.

Manufacturing the Other

Mr. Smith repeated his question and asked whether the Vietnamese and Cham people were identifiable target group of the CPK leadership group. Professor Hinton replied that they were. The cadre he had talked about on page 39 had worked at the Phnom Pros. The information in relation to the sequence of events in Kampong Siem originated in the interviews with the villagers. Mr. Smith inquired whether former Khmer Rouge cadres who were deemed suspect became an identifiable target group. Professor Hinton confirmed this.

Mr. Smith then referred to the speech Who are We from 1978 that Professor Hinton had mentioned. Mr. Smith read a speech that was believed to come from a Revolutionary Flag of July 1977. This speech talked about “we” and “the enemy”.[7] He wanted to know what this passage he had read out in the terms of manufacturing difference based on his comparative studies. Professor Hinton replied that it laid out target groups which could potentially be targeted. He said he believed this speech to have been broadcasted over the radio in 1978.

Mr. Smith referred to another speech which again referred to categories of enemies.[8] He then quoted another document.[9] Third, he read out an excerpt of a Revolutionary Flag of December 1976 and January 1977.[10] Lastly, he quoted another Revolutionary Flag talking about enemies.[11] Mr. Smith asked whether these passages, taken as a whole, provide evidence of the stigmatization of groups or enemies that he talked about in the chapter of manufacturing difference. Mr. Koppe interjected and said he was not sure why he was reading these excerpts after having said he would focus on the treatment of the Vietnamese people, since these excerpts were directed against Khmer Rouge cadres who were accused of treason and working together with Vietnamese. Mr. Smith replied that it was important that the professor gave his expertise on how enemies were viewed as a category and how this enabled Khmer Rouge cadres and others to kill Cambodians before focusing specifically on the Vietnamese. The President allowed the Deputy Co-Prosecutor to continue. The expert confirmed that this was the type of language that he had encountered in his research in relation to the process of stigmatizing the enemy. He explained that self-criticism and criticism meetings, re-education camps and keeping note of someone’s background was a way to monitor people.

De-humanization

Mr. Smith read an excerpt of Duch’s testimony of June 15, 2009, in which Duch emphasized that S-21 was not a prison that adhered to the rule of law and in which prisoners were detained in inhumane conditions.[12] Mr. Smith asked whether he agreed with the statement that it would have been easy for them to kill at S-21, because they were “less than human, namely animals”. Mr. Koppe objected to the questions for two reasons: first based on procedural reasons, since the document had not been presented to the expert in time. Second, it was a testimony of Duch that related to S-21 and that was not dealt with right now. Mr. Koppe said that the expert had no specific expertise relating to the reliability of Duch. Mr. Smith replied that the Prosecution had always been “very giving” in relation to the timing of presenting documents. It seemed, he said “quite pedantic” to object on this ground. As for having the expert comment on this issue, he said that the purpose of the question was to see whether treating people in a de-humanized way made it easier for them to be killed. Mr. Koppe said that he would not object to this question and that he did not understand why he had to refer to Duch’s testimony to ask this question. “Any child would say yes to this question.”

Professor Hinton said that he had completed the book about the Duch trial that was now in press. He answered that the factors taken together, including the de-humanization, made it easier to kill other individuals. It was crucial to have an ideology that people could adhere to. Mr. Smith wanted to know whether it was less likely that people would kill without ideology. Professor Hinton answered that this was correct for the cluster of ideological genocide. In other instances, such as the killing of aborigines, this applied to a lesser extent. Next, Mr. Smith wanted to know whether the cadres undertook ideological manipulation, which the expert confirmed. Further, Mr. Smith wanted to know whether this building of ideological consciousness occurred during Democratic Kampuchea. He affirmed this: the metaphor construction and building was present in the Democratic Kampuchea ideology. It applied to the society in general. Within this re-building of society, some people were more likely to fall into an aggressive state.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Ideological manipulation

At the beginning of the last session, Mr. Smith read out an excerpt of the book, in which Professor Hinton had quoted a Revolutionary Flag:

We must rid in each party member, each cadre, everything that is of the oppressor class, of private property, of stance, view, sentiment, custom, literature, art . . . which exists in ourselves, no matter how much or how little. As for construction, it is just the same: we must build a proletarian class worldview, proletarian class life; build a proletarian class stand regarding thinking, in living habits, in morality, in sentiment, etc. [13]

Professor Hinton said that they wanted to follow the revolutionary line. As for the killing of the Cham, he did not believe that there was a racial intent in the beginning, but over time they were seen as a threat through their inability to sharpen their consciousness as the revolutionary group. Mr. Smith asked why revolutionary consciousness was so critical for the mass killings. He replied that it was the basis for the “pure revolutionary” who was to follow the line.

Mr. Smith asked whether it was an ideological manipulation in the sense of brainwashing how they thought. Professor Hinton confirmed this partially, adding that brainwashing suggested that those who did the brainwashing did not believe in what they were doing – this was not the case here, since they often believed in it and tried making other people believe in it as well. “The top leaders believed in the line and stance,” he said.

Mr. Koppe objected when Mr. Smith asked whether the CPK cadres had been forced to build their revolutionary consciousness by the CPK system and said that this exceeded the expert’s knowledge. Mr. Smith argued that the expert was “well in a position” to answer this question. He said that Professor Hinton was an expert in authoritarian regimes, a classification Mr. Koppe rejected. The objection was overruled. Mr. Smith repeated the question.

Professor Hinton replied that the CPK regime sought to establish a regime in which every single person would re-fashion and sharpen their revolutionary consciousness. This could be seen in the radio broadcasts, writing autobiographies, self-criticism meetings, having education and re-education sessions and the like. Mr. Smith asked Professor Hinton to describe the two practices and how they related to building a consciousness.

The expert answered that the self-criticism meetings came from the idea that it was an ongoing struggle to sharpen their consciousness. Monitoring was another way to achieve this, since people were cautious and conscious about what they were saying. Writing their biographies was another exercise. Different groups had more or less likelihood in being able to refashion themselves as a pure revolutionary depending on the group they belonged to. He believed that this went up to the top level and gave the example of Ieng Sary. This was a form of education that needed to be done. “People didn’t have a choice, they had to do this regularly.”

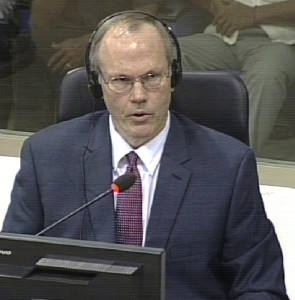

Expert witness Alexander Hinton

Having a proper revolutionary consciousness was “absolutely critical for everyone”. This was how they tried to achieve a “super great leap forward”.

He drew a conclusion to an envelope that could be tighter or closer. S-21, for example, were tighter and not much room was given for decision-making. However, in some aspects, “the envelope of constraint was looser”. He noted that in the case of the Cham that once the idea came up that their consciousness was not to be trusted, they became a targeted group.

There was a brief discussion about a document that the expert wanted to refer to that he had been provided with before. He said that it was crucial that one was a pure revolutionary and did not have regressive consciousness.

Mr. Smith referred to the passage in the book, in which he had quoted an interview with the cadre Teap.[14]

They sent us to be indoctrinated with their ideology, saying that whatever we did, we had to always be dispassionate and resolute. They didn’t allow sentiment between a child and his or her mother and father. They didn’t let us know them. If we expressed feeling for our parents, they’d say we [we building] the garden of the individual and were at fault. Their ideology was the hardest and strictest of all. They didn’t allow us to recognize our siblings! Their slogan was “Anything for the Party!” . . . They asked us, “Comrade, if your mother or father was such a traitor, would you dare to kill them? Could you cut off your feeling toward them? Would you act with firm determination?” . . . None of us could say no. We had to answer that we would dare to do so without hesitation.

The expert confirmed that this was something that Teap had told him. He worked at the same office as Rom. Mr. Smith wanted to know whether this ideology increased the likelihood that Khmer killed Khmer or other groups, which the expert confirmed. Pointing to S-21, he said that the notebooks emphasized the need to cut off their emotions.

Moral restraint

Moving to the last subtopic in relation to the universal factors, Mr. Smith wanted to know what he was referring to when talking about moral restraint. Professor Hinton explained that it was a related issue. He explained that most people had internalized prohibition to kill other individuals. Moral re-structuralization took place to reverse this restraint. He

Mr. Smith read another excerpt, which related to the “right to smash” of 30 March 1976, entitled “Decision of the Central Committee Regarding a Number of Matters”.[15] Mr. Smith wanted to know whether he had seen this decision before. Professor Hinton replied that it was a well-known document that had been cited during the Duch trial. He wanted to know what “to smash” mean. The expert said that Duch had also referred to this and explained that it meant to crush something. Mr. Smith wanted to know whether it meant to kill. Professor Hinton replied that it was one of the more direct euphemisms. Others included “to dissolve”. The moral inhibitions were reduced, people were marked and de-humanized, which made it easier for people to kill others.

Mr. Smith then turned to the synchronization of local norms to these broader factors. He said that the expert had talked about disproportionate revenge, the notion of power and saving face and having honor, and wanted to know whether this was present during Democratic Kampuchea and facilitated the likelihood that mass killings would occur during the period. Professor Hinton confirmed this and said that a number of cadres on the countryside had been educated in pagodas. The Buddhist resemblance provided resonance to the ideology and made it more attractive. He confirmed that this made it more attractive and desirable to kill.

The notion of revenge existed in all societies, he said. However, it was different in each society. It was used as a key term during Democratic Kampuchea. The word “class-grudge” was used by the leaders of the CPK by saying that the people on the countryside were suffering while the people in the cities were “having a good life”. There was a notion of anger that was combined with this class grudge.

Next, Mr. Smith read three extracts. The first one related to anger experienced against oppressors. [16] The second excerpt talked about a “profound rage” that needed to exist before “sweep-cleaning” the enemy.[17] The third passage was also related to inciting anger:

Glittering red blood blankets the earth –

Blood given up to liberate the people:

Blood of workers, peasants, and intellectuals;

Blood of young men, Buddhist monks, and girls.

The blood swirls away, and now flows upward, gently, into the sky,

Turning into a red, revolutionary flag,

Red flag! Red Flag! Flying now! Flying now! [18]

Mr. Smith wanted to know whether this was used during the Democratic Kampuchea. He replied that he was not entirely sure about this Red Flag, but the national anthem was used and very similar to this. Mr. Smith asked whether it was more likely to increase the chances of mass killings or to reduce them. Professor Hinton replied that it was more likely to increase them. The civil war needed to be taken into account leading to a situation in which “there was a great deal of anger”. Mr. Smith wanted to know whether the CPK leadership discouraged or encouraged this anger. Professor Hinton replied that “it is clear” that the CPK encouraged it.

As for the patronage system, Mr. Smith said that the expert had stated that one had to understand the patronage and power system to understand why the purges took place. The expert said that the notion of dependencies and personal relationship was omnipresent in Cambodia. The same notion that there were strings of people was also present during Democratic Kampuchea. This also applied to strings of perceived treason. This was reflected in confessions that included a structure related to these strings. He explained that this system of strings and patronage existed prior, during and after Democratic Kampuchea.

Mr. Smith read two documents. The first was a report from an office.[19] The next document was a Revolutionary Flag of June 1977.[20] Mr. Koppe interjected and said that the document was contentious. The expert was in no position to answer this question. Judge Fenz said that the question had not been asked yet. Mr. Smith said that his question related to the search for strings and how patronage and power was used. He then asked whether looking for strings was a practice that was partly informed by the cultural understanding of patronage and power. Professor Hinton said that this was correct. It was also a form of socio-political organization, he said.

The President adjourned the hearing. It will continue tomorrow March 15 2016, at 9 am with the testimony of this expert.

[1] E3/38.

[2] E3/87.1.1.

[3] E3/87.1.1, last page.

[4] E3/3346, p. 281, 00431723 (EN), no Khmer or French translation available.

[5] ibid.

[6] E3, at p. 33 , 00431475 (EN).

[7] E3/743, at 00476163 (EN), 00062886-87 (KH), 00487687 (FR).

[8] E3/135, at 00142906 (EN), 00062805 (KH), 00487721 (FR).

[9] E3/727, at 00185327-28 (EN), 00064560-61 (KH), 00524454-55 (FR).

[10] E3/25, at 00491397 (EN), 0063004 (KH), 00504017-18 (FR).

[11] E3/742, at 00478496 (EN), 00062986 (KH), 00499754 (FR).

[12] E3/5799, 15 June 2009, at 00341719-21 (EN), 00341910-11 (KH), 00341817-19 (FR).

[13] E3/3346, at 00431637-38 (EN), page 195-196.

[14] E3/3346, at 00431704-5 (EN), 262-263.

[15] E3/12, at 00182809 (EN), 00000758 (KH), 00224363 (FR).

[16] E3/346, p. 74.

[17] E3/743, at 00476167-68 (EN), 00062892 (KH), 00487692 (FR).

[18] E3/346, at p. 84.

[19] E3/178, at 00342709 (EN), 00275558 (KH), 00623305-06 (FR).

[20] E3/135, at 00142912 (EN), 00487736 (F)R, no Khmer ERN available.