Expert Says Evidence Suggests Genocide of Vietnamese Took Place

In today’s session in front of the ECCC, Professor Alexander Hinton continued his expert testimony. While yesterday’s hearing was largely focused on factors leading to mass killings and genocide in general, today’s discussion dealt with the killing of Vietnamese specifically. In the expert’s view it was clear that a genocide had taken place, but he acknowledged that the ultimate judgment to be decided by the Chamber. He also talked about the importance of Buddhism and Buddhist rituals in everyday situations in Cambodia and told the Court that the long-lasting consequences of the prohibition of these was often overlooked: for example, not being able to burry corpses according to Buddhist rituals had as a consequence that Khmer people sometimes felt haunted by spirits even today, he said. Moreover, he pointed out that perpetrators should not be demonized, since this would lead to the de-humanization of this group of people. During the last session, the credibility of his claims regarding the occurrence of mass killings was challenged by Nuon Chea defense lawyer Victor Koppe, who alleged that the expert made “sweeping claims” without apparent sufficient sources.

Long-standing animosities towards Vietnamese

The Trial Chamber Greffier confirmed the presence of all parties. Nuon Chea followed the proceedings from the holding cell. The floor was granted to the International Deputy Co-Prosecutor William Smith. Mr. Smith opened his line of questioning by moving to the third set of questions, namely those relating to the treatment of the Vietnamese in Democratic Kampuchea. He wanted to know how the Vietnamese were portrayed in Cambodia historically. He answered that you could find long-standing stands of anti-Vietnamese sentiments throughout history. This also related to Vietnam taking land of Cambodia after the French colonial rule. He said that around 400,000 Vietnamese were thought to have lived in Cambodia in 1970. Mr. Smith wanted to know how ethnic Khmer were viewed historically and referred to Angkor and the decline of it.[1] At this point, International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel objected and said that counsel had referred to “the Vietnamese” and asked this to be clarified. He said that there was “continuous mixing up” of Vietnamese citizens and Vietnamese foreign policy. The objection was overruled and Mr. Smith repeated his question and inquired about the Vietnamese race.

Professor Hinton replied that the term race was problematic. As for the specific question he replied that there had been a decline of Angkor during the French, which was reversed afterward. There was a heightened national consciousness stressing the Khmer purity. In contrast, the Vietnamese were seen as using trickery and not being pure. The term yuon was often used signaling the hatred towards the Vietnamese. Mr. Smith wanted to know whether it was correct that the Vietnamese were seen by the Khmer historically in a demeaning way, which the expert confirmed.

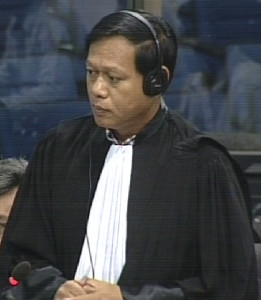

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Next, Mr. Smith inquired how the Vietnamese soldiers living in Cambodia and the civilians living in Cambodia were seen under the Lon Nol regime. He answered that they were seen as outsiders trying to undermine Cambodia. He said that what happened to the Vietnamese could be seen as genocide even under the Khmer Republic era. Professor Hinton said that of the 400,000 Vietnamese people who were said to have been living in Cambodia in 1970 half of them had been expelled or killed at the end of the Lon Nol regime. As for propaganda against the Vietnamese under Lon Nol, Professor Hinton said that it seemed to have been omnipresent, but he did not want to give a definite answer, since more research needed to be done.

Treatment of the Vietnamese under Democratic Kampuchea

Turning to the Democratic Kampuchea regime, he recounted that there were around 200,000 ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia. The demographic estimate guessed that virtually “all of them” were thought to have been killed after a number of them had been expelled. [2]

Mr. Smith referred to a Revolutionary Flag of April 1976 which talked about the expulsion of foreigners.[3] He asked who they referred to when talking about “foreigners” who had been expelled. Professor Hinton confirmed this. Mr. Smith inquired what effect such a Revolutionary Flag had when they were taught to cadres and the like. Professor Hinton said that there was cumulative radicalization depending on the threat that was felt. In 1976, the tensions were heightened since the conflict with Vietnam broke out. Cham, for example, were not seen as a threat from the beginning and it was important to distinguish two different threats. As for cumulative radicalization, he said that there was not always a plan to kill people from the start. He relied on historians such as David Chandler and Ben Kiernan, but also on primary data from Kampong Siem, such as interrogator notebooks using the term yuon. Thus, he said, he had used a range of different sources to come to this conclusion.

Mr. Smith asked the reasons why particular people were arrested could be seen in the confessions instead of from the fact of the purges themselves. He answered that he used numerous sources, including work of David Chandler and DC-Cam archives.

Mr. Smith quoted from Professor Hinton’s book, in which he had talked about the perception of Vietnamese as enemies. [4] He further referred to another excerpt in which he had mentioned Grandmother Yut. [5] Mr. Smith wanted to know whether he knew Grandmother Yut’s full name. Mr. Koppe interjected and said that they believed to have identified Teap. Before answering any questions about what Teap had told him, this person should be identified. The person the Defense Team thought to have identified the person and this person had been interviewed four times by the Co-Investigator’s. Since it was an observation and not an objection, Mr. Smith was instruction to move ahead. He repeated his question. The expert said that it seemed that Yeay Yut was most likely Prak Yut who had also testified in front of the court.

Mr. Smith sought more detail about the letter that he had referred to in his book that Teap had said instructed them to smash the enemies. The expert said that the letter had not been preserved. Teap had told him that Cham people were rounded up and killed. The number of Cham was greater than the one of Vietnamese in this area.

Mr. Koppe objected and said that the Co-Prosecutors had never requested to call the person that they thought was Teap. Neither the Co-Prosecutors nor the Chamber had considered the witness to be particularly important previously, and now they relied on his anonymous statements. It was, Mr. Koppe argued, important to identify whether this was the same person. Mr. Smith replied that Mr. Koppe would have time to question the expert on this later. The bench conferred for a few minutes and asked whether the expert could provide the Chamber the real name of Teap. Professor Hinton replied that this was difficult due to two reasons: First, he had to adhere to the human subjects protocol, which needed to be followed. Second, he did not know the name off-hand and would have to go back to his research material. He had converted the name with a code sheet, which he did not have with him right now.

Mr. Smith then read another excerpt of Professor Hinton’s book, in which Professor Hinton had quoted Teap as saying: [6]

cadres would “always talk about CIA and KGB ‘enemies’. . . later on, thought, they stopped talking as much about the CIA and Lon Nol regime and began speaking about the ‘arms and legs of the Yuon’ and ‘Yuon strings.’ . . . If a person was ethnic Vietnamese, it was certain that they wouldn’t survive. Once they were discovered, that was it.

He wanted to know whether this was an accurate statement of what Teap told him, which the expert confirmed. He could not remember the reasons Teap told him for this certainty to been killed if being discovered to be Vietnamese. He said that his interviews were taped and transcribed.

Teap referred to two things: Vietnamese in Cambodia that were an internal enemy, and external enemies, such as Vietnamese outside Cambodia.

Mr. Koppe interjected and said that they believed that Teap was no cadre, even if this was what the expert asserted. The expert could not remember his specific function.

He said that a person who was a district chief and a couple of villagers had told him that all Vietnamese had been killed, but he was not entirely sure about the number.

Many of the people were in Krala during the Khmer Rouge. He could not remember how many people had told him. Around half dozen or a dozen people had mentioned the Vietnamese.

Mr. Smith put to him an interview of another witness who had also worked at Krala. This witness had talked about orders given by Ta Long who gave orders to arrests of Cham and Vietnamese people. [7] People did not know about particular orders to arrest Cham, but they could observe the difference in treatment. [8]

The person who worked at the security center, Khel, did not talk about Vietnamese and Cham people being taken to Wat Phnom Pros Phnom Srey. Instead, they were killed near sites.

Incitement to mass killings

After the break, the floor was handed to the Co-Prosecutors. He clarified that the Co-Prosecutors had asked the witness that the defense thought to be Teap to be called. Moreover, the Prosecution was not certain whether it was indeed the same witness. He gave the relevant ERN numbers. [9] He asked the Defense Counsel to refrain from objecting too much. Mr. Koppe replied: “Now you know how it feels from being stopped from asking questions all the time”.

Mr. Smith asked whether it was correct that Phnom Pros, Phnom Srey was in operation before and after the purges, which the witness confirmed.

Mr. Smith then put another witness’s statement forward who had lived in Tuol Beng in Krala District. This witness had talked about the arrests of Cham and Vietnamese and Khmer people who had Vietnamese wives. [10] Mr. Smith wanted to know whether he received similar information that husbands, wives or children of ethnic Vietnamese were arrested and killed. He answered that people spoke about the arrests of Vietnamese families. In “virtually every case” they would take the whole family when it related to ethnic Vietnamese.

Mr. Smith read out a report from Ang Ta Saom Commune Report that talked about the treatment of the Vietnamese.[11] The expert said that the report fit in the process of manufacturing difference by seeking out differences of “the other”. The report also showed the ambiguity that sometimes existed to determine whether someone belonged to a group or not.

Mr. Smith further referred to a Phnom Penh Domestic Broadcast, which included a Khieu Samphan speech of the anniversary meeting 15 April 1977. In this speech, Khieu Samphan had said to “suppress all stripes of enemies”. [12] The expert said that it was not possible to determine that he referred to specifically Cham or Vietnam. Instead, it could be interpreted in general as including Cham or Vietnamese, but not exclusively referring to them. This general referral to the enemy was, he said, was often present. It fit into general incitement against “the enemy”.

Mr. Smith wanted to know whether the use of this broad language increased, decreased, or did not have any effect on particular target groups being victims. He replied that it would increase the likelihood, since it generally incited. However, it did not incite to target specific groups.

Mr. Smith to the April 1978 edition of Revolutionary Flag, which reprinted a speech given by Pol Pot. [13] In this speech, Pol Pot had talked about one Khmer troops being able to defeat 30 Vietnamese troops. Mr. Smith asked whether this CPK principle of killing 30 Vietnamese being killed for one Cambodian being killed had any effect on the killing of Vietnamese in the country. At this point, Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé objected and said that the Co-Prosecutor had avoided the context. This speech was directly linked to the armed conflict. The objection was overruled. The expert said that this was language that incited genocide. The word yuon was used both against ethnic Vietnamese who lived in Cambodia and those who actually lived in Vietnam.

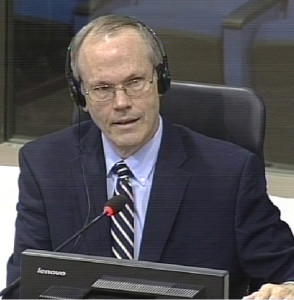

Expert Alexander Hinton

Next, Mr. Smith referred to an excerpt of the same speech.[14] He inquired whether this type of statement had a likelihood to encourage or discourage the killing of Vietnamese civilians in Democratic Kampuchea. Professor Hinton affirmed this. The word “seed” in particular was a metaphor for the destruction of a race. Revolutionary Flag May- June 1978, which referred to the yuon and how to attack them.[15] At this point, Mr. Koppe objected, since the excerpt had talked about “land-swallowing yuon”, which clearly referred to Vietnamese foreign policy. Mr. Smith argued that he had not said that every time an excerpt mentioned yuon that they referred to Vietnamese civilians and was not misleading the witness. The expert replied that there could be third groups: Vietnam, ethnic Vietnamese and the East Zone group associated with Vietnam.

Mr. Smith asked whether Vietnamese civilians living in Cambodia targeted for killing during the Democratic Kampuchea regime, which the expert confirmed. “The case seems strong and compelling”. He said that the CPK standing committee had the main control over this movement by running propaganda and being responsible for the army. With this, Mr. Smith finished his line of questioning.

The floor was granted to the Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers. International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud said that she focused on the impact of the policy and crimes that the Chamber was seized with. She focused on the impact of policies on Buddhists and families.

Buddhism

She said that he had said in his book that Buddhism was one of the three pillars in Cambodian society, which played a social, moral and educational role in everyday life. She asked him to explain the significance of Buddhism in Cambodian society prior to Democratic Kampuchea. He answered that it was an important factor before Democratic Kampuchea. In addition to its social, moral and educational role, he added ritual goals. People were educated at pagodas. Basic precepts of morality were taught in Buddhism, including the precept not to kill. In Democratic Kampuchea, Buddhist statues were destroyed and with it a central pillar of Cambodian society. Moreover, not being able to bury deceased people according to Buddhist rituals haunted people, since they believed that the souls did not find any rest. Thus, it was a pillar of life. When this was destroyed, it was also important to recognize its effect into everyday life today.

Ms. Guiraud then said that he had said in his book that Cambodians sought protection from spirits, Buddhism and people. She wanted to know what the impact of the destruction of this system of protection offered by protection on the people. He answered that not enough attention had been paid to the everyday lived experience of Cambodians. More studies needed to be conducted on this topic.

According to the expert, the destruction Buddhism brought people out of balance. Cambodian believed in equanimity and taking one of these pillars away was destructive. He pointed to the notion of Buddhism that was also present in this court. Not being able to perform the rituals for the dead was of great significance, he said.

She inquired whether this led to a greater acceptance of Angkar. Professor Hinton replied that Angkar held different connotations. There was an official use of Angkar since the Duch trial, while there was a more colloquial use elsewhere. People on the countryside often interpreted it almost as a deity. He argued that it was a symbol with many different meaning. Angkar was “feared in many different ways, because Angkar could kill”.

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

Next, Ms. Guiraud asked him to explain Buddhist themes and terms that were used during Democratic Kampuchea. He gave the example of Grandmother Yut when her husband was shot, the notion was that she could renounce her husband. The notions of attachment that needed to be renounced was also prevalent in Buddhism. The Khmer Rouge would use these terms and recast them in terms of their ideology.

“Massive rebuilding of Buddhism” took place during UNTAC. In Marxist-Leninist ideology, religion was seen as the opium of the people. Thus, it needed to be removed. Destroying religious rituals could be seen, he argued, as an attack on a national group itself.

Ms. Guiraud turned back to the “need for protection” and sought his clarification about the importance of the neak ta. He replied that the neak ta was part of everyday life in Cambodia. They were part of religious rituals. There was a mixture between the neak ta and Buddhism, for example. They were sometimes believed to have been ancestors coming back to their villages. Those who lived close to villages were believed to be able to give protection. They played a crucial part in everyday life. At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for the lunch break.

Personal strings

After the break, Marie Guiraud resumed her line of questioning. Professor Hinton confirmed that the centralized and personalized relationships as part of a protection system was operative in Cambodia. The personal links continued to exist during the Democratic Kampuchea. Thus, Grandmother Yut brought with her relatives when she moved to Kampong Siem.

Ms. Guiraud said that he had said that life was better for people in the cooperatives and that cadres had been replaced in order not to create any ties with the local people. [16] Professor Hinton explained that these personal ties were seen as threats to the Democratic Kampuchea regime. In Region 41, they would rotate those who conducted the killings. In some circumstances people could protect the people they had personal ties with a little bit.

The dynamics varied temporarily and spatially. The personal strings continued to determine actions under the Democratic Kampuchea. The Khmer Republic officials were seen as having threatening links.

The role of the family and children

Ms. Guiraud then wanted to know more about the role of the family and why it was important for the Democratic Kampuchea regime to destroy the entity of the household. He replied that they were potential sources of threats to the regime, since they posed an alternative source of loyalty. Moreover, Angkar re-phrased the entity of families by arranging marriages and presenting Angkar as performing a parental task that people needed to feel grateful for. Children were often separated from their families. Many people, he said, were upset about having to eat communally and not being able to eat in their family. The general atmosphere of distrust also splintered families.

Ms. Guiraud further inquired about the role of children that they played in the revolutionary process.[17] He said that this referred to revolutionary consciousness and personal tendencies. Those children that had not grown up in a capitalist society they were seen as being more pure. They, the Khmer Rouge alleged, would be able to lead the society to a better future. There were often bonds of families that were scattered during the Khmer Rouge regime. He pointed to arranged marriages. Due to the fear of stigmatization, many families remained together and did not divorce. Moreover, some had children from these arranged marriages.

Different groups of people

The New People were stigmatized in general and being seen as having a less sharp revolutionary consciousness due to the capitalist environment they lived in before. Base People, he pointed out, also suffered. New People suffered more in general, but the suffering of the Base People should not be neglected. Ms. Guiraud asked what the impact of the Democratic Kampuchea regime was on Base People and the impact of collectivization. He said that the collectivization of groups was problematic, since it implied that they were a homogenous group. One had to look at Base People as a group that changed over time and entailed different subgroups.

There was a reversal of status during Democratic Kampuchea. There could be localized effects of taking revenge against people they had held “a grudge” against already before the Democratic Kampuchea regime. He gave the example of a base person who held a grudge against a previous teacher and killed him. This killing was enabled due to the reversal of status.

When she asked about the role of women and men, he replied that women had been empowered in some ways in the household and with regards to money, for example. The Democratic Kampuchea regime in general empowered women by putting them in high positions of power. There was an attempt to eradicate gendered differentiation. They tried to create a “unisex being”. They attempted to create equality by empowering women in some regards, even if they were disempowered in others.

Ms. Guiraud then wanted to know whether the trend to abandon the pronoun I in favor of using the term “we” had an impact on people in Cambodia. He said that it signified the emphasis of the group over individuals. The individual distinctiveness “was muted”, which was not welcomed by many people. They became a uniform subject. This topic had been taken up, he said, by Rithy Phan in his movie The Missing Picture. Men and women still existed, but they were more seen as a universal and uniform being. She inquired whether he observed this trend to use “we” instead of “I” when he came to Cambodia. He replied that it was still used, but “I” was more persistent. She then gave the floor to her colleague Lor Chunthy.

Civil Party Lawyer Lor Chunthy

Mr. Chunthy sought for more clarification regarding connection of Buddhism and the Democratic Kampuchea party line. He replied that an example was that by following the line of Buddhism one would reach nirvana, which corresponded to following the party line. Another example was the aim of detachment that was both present in Democratic Kampuchea ideology and Buddhism. The notion of mindfulness in meditation also emerged during the Khmer Rouge, since one was expected to be mindful in following the party line.

With regard to ideology, he said that this was used more for regimes with more uniform ideas. However, the Khmer Rouge also used the word in terms of the “capitalist ideology”, which had a different meaning.

As for parallels between the Democratic Kampuchea and other ideologies, Professor Hinton said that one could draw them between the Democratic Kampuchea ideology and Marxism, Leninism, Stalinism, and the North Korean model

He said that the lesson of the Duch trial was what he referred to what he called effacing convictions. When having beliefs that lead to the de-humanization of another person and to disregarding the humanity of another person, “we efface […] the humanity of that person”. He stressed the danger of these effacing convictions.

Sharpening of revolutionary consciousness

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne wanted to know whether he had understood him correctly that he had said yesterday that it was possible for everyone to be refashioned. He confirmed this, but said that there was a difference in the likelihood of sharpening the consciousness. This likelihood was viewed to have been diminished by the Khmer Rouge over time. He gave the example of Cham and said that they were viewed as being unlikely to be able to refashion their consciousness. When the conflict with Vietnam increased, the likelihood of being able to refashion ethnic Vietnamese were seen to have diminished, even if the animosity existed previously. Chinese people, as a group, were being targeted because the likelihood of sharpening their consciousness were seen as being diminished.

Judge Lavergne then turned to the fate of the Cham. He wanted to know whether other factors, such as religion, were taken into account when targeting that group, and not only the rebellion that had taken place. He clarified that the rebellion was not the only factor playing into this, but a number of factors. Religion in general for example was also a factor. He said that the Cham fell into a religious category and were targeted in part because of their religion that did not fall under the notion of uniformity. He further elaborated that here were stereotypical and racial association with Vietnamese. At the same time, the deteriorating relationship with Vietnamese played a role.

As for the eating of human gallbladders, he said that this was often perceived as having been conducted by a “savage”, which in turn de-humanized the perpetrator. It was important not to do this. He gave the example of the Duch trial, but said that he was certain that media also talked about the accused in this case in a de-humanizing way.

Judge Lavergne then wanted to know whether perpetrators went beyond what was expected by them, which the expert confirmed. Professor Hinton explained that these actions were nonetheless not completely disentangled from the larger ideology and could be linked.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Sources of the expert

In the last session, the floor was given to the Nuon Chea Defense Team. Mr. Koppe asked whether he agreed that his three main sources were:

- existing scholarship

- interviews with people in Region 41

- original Democratic Kampuchea documents

He confirmed this, but said that his first source were interviews as well as data collections. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was fair to say that he mostly relied on the work of David Chandler and Ben Kiernan for the scholarly work, which the expert confirmed. He said that David Chandler had been supportive, but he could not recall having said that Ben Kiernan was supportive of his work. He had not interacted with him as much. Mr. Koppe said that he had said this in his foreword. He had interacted with Ben Kiernan as well, but predominantly with David Chandler. The latter had a stronger influence of the expert’s work. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether there were points in which he differed to David Chandler or Ben Kiernan about what happened in Democratic Kampuchea. He replied that there seemed to have been a consensus about the purges and where they occurred. There were differences in the understanding and labelling of groupings and networks. When Mr. Koppe repeated his question on whether he differs with any of the scholars about what happened in Democratic Kampuchea, Mr. Smith objected and said that counsel should be more specific. Mr. Koppe gave examples of the reasons for the purges, the treatment of the Vietnamese and the like. Mr. Koppe asked whether he had heard of a notion called the Standard Total Academic View. He replied that this was an early view by Michael Vickery, and it was important to note that there was variation of the centralization of control. People disagreed over the degree of central control and its causes and effects. When Mr. Koppe asked whether he agreed with Ben Kiernan about purges and reasons for these, Mr. Smith objected again based on the broadness of the question. The objection was overruled.

The expert said that he had a different perspective, since he looked more at culture. Mr. Koppe said that he had the feeling that he was “most of the time” reading Kiernan’s or Chandler’s view and nothing new in relation to S-21. He answered that he had conducted further research.

As for the number of interviewees, he said that it was not correct that he spoke to around ten to fifteen people in the village. Instead, he spoke to over a hundred people. Mr. Koppe wanted to know what the mechanisms were for him to ensure that the people he talked to were representative of the village, sub-district, district or the country. He answered that his goal as an anthropologist was to understand the cultural dimensions of what had taken place in contrast to handing a survey. His concern was more to understand the experience in the village. Mr. Koppe said that he had referred to “all Vietnamese have been killed” and about “the Khmer Rouge”. The expert replied that the demographic data was suggestive and linked to scholarship that had been done by Ben Kiernan and Ysa Osman. Moreover, he had been to Cambodia “many times” and followed the Duch trial. Thus, his knowledge was broader than what he relied upon in his book. Mr. Koppe said that it was important for the defense to understand where the claims were based upon. He replied that his basis was indeed interviews and Ben Kiernan’s work, but also the evidence that had been presented in court. He said that “seems clear that there was a genocide committed against the ethnic Vietnamese” but that the final verdict would determine this. Another important factor was Democratic Kampuchea broadcasts, notebooks and other materials.

Disagreements with other scholars

As for disagreements, he said that he was aware of disagreement about whether the Democratic Kampuchea regime was racist or driven by Marxist-Leninist ideology in the foremost. Stephen Heder, for example, considered the killing of ethnic Chinese should be considered genocide which Ben Kiernan did not think.

Mr. Koppe asked whether he knew anything about “the problems that Kiernan encountered” when his program became part of DC-Cam and the questions that Morris raised whether Kiernan could be seen as an objective person being involved in DC-Cam. He answered that he became an academic advisor after this dispute had been taken place. Mr. Koppe clarified that Kiernan himself had said in his book that the views about the Marxist-Leninist might have threatened his objectivity. He answered that there was a degree of disagreement whether what happened was due to Marxist-Leninist views or due to some prevailing racism.

Reliability of sources

Mr. Koppe then wanted to know how he ensured how what they had told him was actually what they experienced. He answered that he used the method of triangulation and tried to confirm the information with other sources. He gave the example of Grandmother Yut who had testified in court and confirmed what he had written. Moreover, he argued that his account had “by and large” been confirmed.

Mr. Koppe asked how he had tried to verify the claim that Teap had made about Grandmother Yut having killed her husband. He answered that it was difficult to track down cadres. Grandmother Yut did not acknowledge having shot her husband, but she had acknowledge that she “did not shed a tear” when her husband was taken away, which confirmed the theory that she had detached herself from her husband.

Asked about Teap, he answered that he had been referred to by other people as a cadre. Locally, people viewed those who worked in an office and held power as a cadre. He could not recall whether Teap referred to himself as a cadre. Since a civil war was still ongoing during the time, people were often not ready to admit that they were Khmer Rouge cadre. It was therefore difficult to find people admitting this. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was fair for him to say that when he spoke about “the Khmer Rouge” or “a CPK policy” to kill the Cham laid on secondary sources and not based on interviews with cadres who could know. He replied that he talked to more people and that many people mentioned “over and over again” that Cham had been taken away.

Mr. Koppe told him that his problem was that he made “very sweeping statements” about Khmer Rouge policy and infrastructure being an anthropologist. He said that he sought transparency as for the sources of these claims and generalizations. Mr. Smith objected and said that this question was too broad. Mr. Koppe asked for specific sources. He answered that his sources were footnoted in his book. Moreover, he had done further research after he had finished his book. He provided the example of the term yuon that had a negative connotation to it. Moreover, other scholars had characterized it as genocide. This statement was in a sense sweeping, but there was a large number of evidence supporting this.

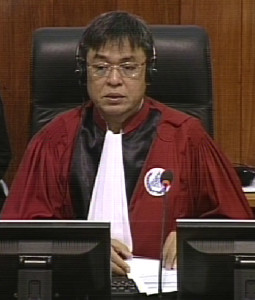

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

Mr. Koppe asked whether he was saying that to use the word yuon meant that someone was racist and that mass killing would occur. Professor Hinton replied that one had to be careful in assessing this, but that often people used this word with a racial undertone. This crystallization of difference contributed to a stigmatization of others and contributed to hatred.

Mr. Koppe gave the example of Late King Father Sihanouk who used the word “land-swallowing yuon” in a speech and asked whether this meant that he was racist. Professor Hinton answered that out of respect for late King Father Sihanouk he would not give a direct answer. In general, using words which were used with a negative connotation could have racist overtones. This was, he argued, the case of the word yuon. He cited an article by Penny Edwards who looked at the use of this term.

Mr. Koppe requested the expert to revisit the speech by Late King Father Sihanouk of 1979 until tomorrow.[18] The President adjourned the hearing. It will continue tomorrow, March 16 2016, at 9 am with the testimony of Professor Hinton.

[1] p. 215.

[2] p. 218

[3] E3/7591, at 0062749 (KH), 00499717 (FR).

[4] E3/346, at 00431661 (EN), p. 219.

[5] At 00431596, p. 154,

[6] At 00431661, at p. 219.

[7] E3/9666, at 01072507 (EN), 00993574-75 (KH), no French translation available.

[8] Ibid., 01072509 (EN), 00993577 (KH).

[9] E3/9667, E3/9453, E3/9548.

[10] E3/9656, at 01034899 (EN), 00987139-40 (KH), no French translation available.

[11] E3/2435, at 00322141 (EN), 00271001-02 (KH), 00612225 (FR)

[12] E3/200, 00004165 (EN), 00292804-05 (KH), 00612166 (FR).

[13] E3/4604, at 00519834 (EN), 00064713 (KH), 00520344 (FR).

[14] E3/4604, at 00519836 (EN), 00064717 (KH), 00520348 (FR).

[15] E3/727, at 00185333 (EN), 00064567 (KH), 00524460 (FR).

[16] At p. 265.

[17] p. 130.

[18] E3/7335.