Nuon Chea Addresses the Court in Response to Expert Testimony

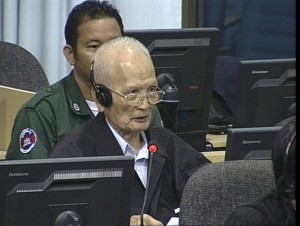

Today was the last day of expert Alexander Hinton’s testimony in front of the ECCC. The hearing focused on his understanding of the word yuon, whether it had racist undertones and whether the use of it during Democratic Kampuchea incited mass killings. At the end of the day, co-accused Nuon Chea addressed the Court and rebutted Professor Hinton’s understanding of this term.

Preliminary remarks

At the beginning of the hearing, Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn informed the parties that Judge Claudia Fenz was not present due to health issues. She was replaced by Judge Martin Karopkin. All other parties were present with Nuon Chea following the proceedings from the holding cell.

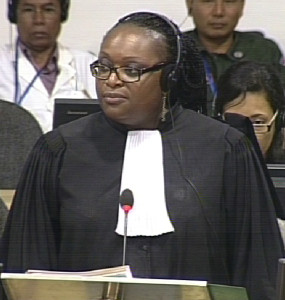

International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

The International Deputy Co-Prosecutor first requested to hear submissions this afternoon and not Monday with regards to a request by the Office of the Co-Prosecutors (E390) to call a new witness. Second, he requested that the Khieu Samphan Defense Team provide the date of date of documents if they were contemporaneous, the type, the person who was it sent by, the person who it was received by, the date of an incident, the relevant location (province, sector, zone) and the nature of the person. He said that otherwise it was difficult for the expert to comment on new pieces of evidence without any context, since he had been given 4,000 pages of documents that he could not have read. Third, he requested to provide the expert with a copy of Ben Kiernan’s map of Democratic Kampuchea zones.[1]

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé noticed with regards to E390 that they had received a courtesy copy of the request to call a new witness for the upcoming segment. She replied that it was in the interest of the proceedings that all parties be prepared, that they be given more than 24 hours to prepare. She stated that she understood the need to proceed quickly, but that equality of arms should be respected.

Regarding the specific conditions that the Co-Prosecutor had asked be respected, Ms. Guissé said that she was “somewhat surprised”, since the Co-Prosecutor had not been mindful of the same criteria. She said that Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe had been scolded for presenting his own narrative and for asking leading questions under the guise of giving context. She pointed out that the Co-Prosecutors could object to questions they considered inappropriate at the time they were asked.

The President reminded the Khieu Samphan Defense Team not to interrupt the expert when he gave answers. He then allowed the Co-Prosecutors to give the map to the expert. The document was also provided to the defense counsel.

Racism and political dissent

Ms. Guissé started her examination by apologizing to the expert for the delay. She then referred to an article by Stephen Heder that criticized Ben Kiernan’s arguments.[2] Heder had argued that being racially or physically Khmer was no protection and that punishment for treason was based on political grounds. The witness replied that Stephen Heder was primarily stressing the importance of Marxist-Leninism and the attempt to refashion certain groups. When considering the events of 1976 and 1977, the notion of cumulative radicalization could be better applied. He explained that his interpretation was that, although there had been racism beforehand, the Cham became a specifically targeted group in 1976 after attempts at resistance, for example.

Ms. Guissé then asked him to focus on the saying that someone had a “Khmer body with a Vietnamese mind.” Professor Hinton replied that this phrase along the lines of yuon could be used in different ways. As a scholar, in order to understand the events taking place on a micro-level, he also relied on secondary sources to understand the context.

She then asked whether he had looked at the minutes of the Standing Committee of 1976 when doing his research.[3] He answered that it was difficult to remember, but that he thought he had not seen it before.

Democratic Kampuchea Defense Minister, Son Sen and Vietnam Communist Party delegations led by Nguyen Xuan Hoang, Phnom Penh Airport, August 1975. (Source: Documentation Center of Cambodia)

She then pointed to the minutes, in which Son Sen had talked about the guidelines of the party and the negotiation processes with Vietnam.[4] She asked whether he remembered that in May 1976 discussions took place with Vietnam about borders and whether he made connections between what might have happened “on the field” in May 1976 and the negotiation process that took place between Democratic Kampuchea and Vietnam. He replied that his focus was on lived experience. Nyan Chanda and David Chandler had talked about this process. He said that this time was when Democratic Kampuchea tried to assess what Vietnam’s intentions were. In 1975 and early 1976, “things seem to have been more moderate”, while the situation became more radical afterwards. This reflected the broader historical process.

Next, Ms. Guissé referred to a speech by Pol Pot of 17 April 1978.[5] She said she had objected when the Co-Prosecutors had put this speech to him, since they had not pointed out the context. She read an excerpt of this speech, in which they had talked about having “smashed aggressive yuon forces”. She asked whether the dates of January 1977 meant anything to him regarding the fighting between Democratic Kampuchea and Vietnam. He replied that Son Sen had gone to the border to fight at this time. He said that it was clear that it was directed in most part to Vietnamese military. However, by using the term yuon, this could have other overtones that also ethnic Vietnamese civilians were affected by. He thought that this was a form of incitement toward ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia. He said that this incitement was implicit in the language used. At the same time, the historical context had to be taken into account.

She asked whether he saw an appeal or a call to kill ethnic Vietnamese in the extract she had read out, since they were talking about armed forces only. He reiterated that one intention was to “stir up” the troops that were fighting against Vietnam. However, when using the word yuon, it had two meanings: Vietnamese troops, but also stirring up incitement against ethnic Vietnamese. Using this word inspired hate, even when it was directed towards the military troops. When it was mentioned that there was “no seed left” in Cambodia, this seemed to refer more particularly to ethnic Vietnamese.

She asked whether the meaning was not only about enemies in this context, even if the term itself might be used for the civilian populations sometimes. She wanted to know how he deducted from this that it was inciting hatred towards ethnic Vietnamese. As an answer, he gave the example of the aftermath of 9/11, in which Muslims and Arabs were talked about in derogatory terms. Although this was used in a military context, attacks on people who were perceived to be Muslims or Arabs followed. When using racist rhetoric this might incite hatred against ethnic Vietnamese, even if the rhetoric was directed against a military opponent.

She then referred to another speech, in which the fight between Vietnamese and Cambodian forces was mentioned and it had been said that thirty Vietnamese had to be killed for one Cambodia.[6] She asked him where he saw that this incited to killings of Vietnamese civilians. He again pointed to the use of the term yuon. He pointed out that although having a military context and emphasis, it used a word that referred to ethnic Vietnamese in both Vietnam and Cambodia. Sometimes the term was used in a way that had not racist connotations, but in general it was a rhetoric of racist hatred, Professor Hinton said. The term yuon was a diffuse term that stigmatized ethnic Vietnamese both in Democratic Kampuchea and Vietnam. He said that the word was therefore a “general term of incitement”.

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne asked whether she had request for correction between the English and French translation of the document. She replied that she had thought that the Chamber had requested the correction.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Yuon

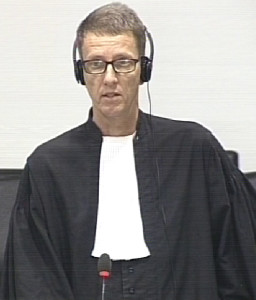

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

After the break, the President announced that the submissions and responses by parties in relation to E390 would be heard Monday morning. Mr. Koppe said that “his client was quite upset” about the use of Mr. Hinton’s word yuon and requested to be able to react to this after the lunch break. Ms. Guissé requested extra time, since they had lost around twenty minutes. Deputy Co-Prosecutor William Smith said that no extra time should be granted, since the Prosecution had been interrupted by many objections. The President said that only little extra time could be granted.

Ms. Guissé then resumed her line of questioning. She referred to the testimony by Prum Sarat, who was a commander during Democratic Kampuchea, who had said that there were not 60 million Vietnamese soldiers who were fighting against 2 million Cambodian soldiers, but that the speech was meant to be an incitement against the Vietnamese army. This witness did not mention Vietnamese civilians.[7] She asked whether the expert focused too much on what he wanted to demonstrate to neglect what people said who actually heard that speech. She said that the speech had been given to celebrate the 17 April anniversary.

Professor Hinton replied that her points raised the point of critical thinking in general. He agreed that all scholars should be self-critical. In terms of reference to the witness, he argued that the word could apply both to the Vietnamese military as well as ethnic Vietnamese. However, this could also incite hatred. He again drew a comparison between the aftermath of 9/11 and the use of the term yuon. He said he looked forward to hearing Nuon Chea speak.

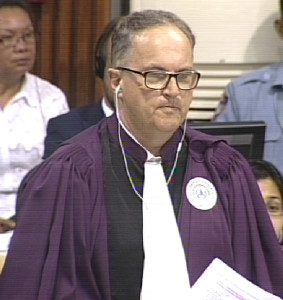

Deputy Co-Prosecutor William Smith

She then turned to the use of the term New People and pointed to an excerpt in his book, in which he had said that New People were also referred to as war slaves. [8] Referring to an article by Stephen Heder who had said that New People were made work side by side with old people and that evacuees were not to be considered enemies.[9] She wanted to know whether the expert was aware of the documents that Stephen Heder had referred to. At this point, Mr. Smith interjected and said that Stephen Heder’s opinion had been taken out of context. He read another part of the document, which said that New People did not have membership rights in the cooperative. Ms. Guissé replied that the document had been given in its entirety to the expert. She then repeated her question. Professor Hinton replied that the senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge had a blueprint for a better society and believed that everyone had the possibility to sharpen their consciousness in 1975. This changed, however in 1976 and 1977, when the groups were seen as having lesser or higher degrees of likelihood. New People were marked and stigmatized as they moved through the temporal and spatial variation. They were seen as seeing a lesser potential for reform that turned into a fear of them engaging in rebellions. This also included students, professors, people who were wearing glasses, former Lon Nol officials. New People were seen with suspicion.

She asked whether he had covered the subject of Revolutionary Flags in his interviews to find out who had access to the documents and how they were disseminated. He replied that the terms were important and distinctions were made between the people. Families of New People were taken away. She referred to the part of the book where he talks about the patronage system and nepotism and wanted to know which areas he was referring to there.[10] He answered that he referred to the interviews he had conducted to find out more about the lived experience of the people. He focused on Region 41.

She referred to his book and wanted to know whether all societies and all states that had endured revolution ended up with some kind of liberation movement or whether this was something particular to Cambodia.[11] He replied that when looking at ideologies from afar, one tended to project own values onto other societies. It was important to take the local meaning and understand the cultural meaning. Thus, the notion of blood referred to a notion of class grudge as well in this cultural context. Thus, it was easy to find commonalities, but more difficult to find the differences. One should not use external categories. For example, people should not be classified under the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder without looking into the local context of what we call trauma. At this point, Ms. Guissé gave the floor to her national colleague Kong Sam Onn.

Mr. Sam Onn asked when the term yuon was used by Cambodians. He answered that he could not give the proper genealogy, but that there was detailed analysis of the use of this term with regards to Democratic Kampuchea. He had studied the use of the term yuon in the context of Lon Nol regime and Democratic Kampuchea and therefore did not want to give a statement about its use in general. He had consulted the Khmer Dictionary several times, but the dictionary was used in the 1940s. He based his analysis on interviews and conversations with Cambodians and secondary sources. The term could also be used in ignorance or without strong racist connotations in another context, but in times of Democratic Kampuchea, the word was brought into ideology inciting hate.

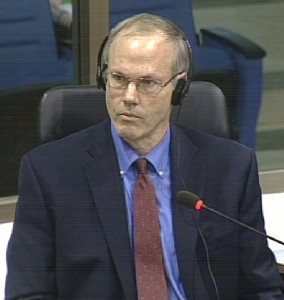

Expert Alexander Hinton

Mr. Sam Onn wanted to know whether he had tried sour soup. Professor Hinton replied that he was familiar with the term samlor machou yuon, but did not want to go into detail about the meaning of this. He gave the example of the racist use of yuon by an “extremely intelligent” person that he interviewed. He said that many highly educated people used this term. The word was also used by politicians at the time.

Mr. Sam Onn asked whether it was appropriate to say that the Khmer people did not use any other word that carried the equivalent of yuon. Professor Hinton replied that he would never say that no other words were used. Combinations with the word dog or other sets of associations were possible.

Mr. Sam Onn then wanted to know whether Cambodia was under the effect of the Cold War, which the expert confirmed. He wanted to know whether Cambodia was used as “an experiment” or a stage between the two blocks. He replied that one had to look at the socioeconomic upheaval as well as geopolitics, which he confirmed as having been a factor. One factor that played a role was the US bombing that intensified in 1973. Albeit not causing the violence that took place later, this helped the Khmer Rouge to power. It also increased anger. He clarified that “you cannot explain the genocide that took place directly as the outcome of the bombing”. Mr. Sam Onn inquired about a plan to unite Indochina and use one currency.

He believed that the leaders of the CPK had a vision for a better world that incorporated social justice. He said that it was “unfortunate” that some groups were excluded and exterminated. He said that this resulted in massive violence. At this point, Mr. Sam Onn finished his line of questioning.

Nuon Chea addresses expert

Mr. Koppe requested for Nuon Chea to be able to address the court for ten to fifteen minutes. Mr. Smith wanted to know whether this meant that Nuon Chea waived his rights to silence and would react to questions. Mr. Koppe replied that he was invoking his right to comment and was “not opening up” to questions, and certainly not by the Prosecution. Mr. Smith said that usually this meant that the right to silence was waived. Co-counsel for Nuon Chea Son Arun said that the term yuon was extensively discussed during the hearing and that the expert still stood by his position that it carried a racist connotation. This was why Nuon Chea wanted to react.

The President instructed to bring Nuon Chea into the court room.

Nuon Chea thanked the President for the opportunity to address the Court. He then said that

“I have listened to the testimony and I felt uncomfortable with that.” He said that he had referred to the 1967 Khmer dictionary by Samdech Chun Nath that defined the term yuon and did not include any racist connotation. He claimed that Democratic Kampuchea “did not mean to incite anyone. . . . And actually Pol Pot gave instructions to us that we should not regard them as our hereditary enemy. They were our friends, but we had contradictions with them, and that is the express instruction from Phnom Penh.” He insisted that Pol Pot had never considered them as hereditary enemy, even if Cambodian people in general might sometimes consider Vietnamese people as such. As for the instructions to kill more yuon than Cambodians, he reiterated that these were the military tactics of Democratic Kampuchea, since they had a smaller army and did not refer to the killing of civilians.

He then asked the expert: “Thus far, [did] Vietnam actually forfeit their ambition to swallow and grab Cambodia? Ad my second question . . .: you are an American citizen and you know that US dropped bombs for 300 days and nights and as a result many houses and pagodas and many infrastructures were destroyed, including the lives of people: do you consider that this is a crime of war […] and genocide?

Mr. Smith said that the statements did not tally with what the Prosecution said. The expert had not had access to the case file. He queried whether the expert should be asked to react without having access to the case file. As for the statement by Nuon Chea that Pol Pot never used the term hereditary enemy, he referred to the Statement of the Government of Democratic Kampuchea of 2 January 1979, in which he had referred to the hereditary enemy.[12] Mr. Koppe said that the Co-Prosecutor was “feeding the expert” with an answers. Moreover, he argued that the term was rightfully used at the time, since Vietnam was invading the country.

The President gave the floor to the expert. He replied that the views of the accused had been “too absent” and thanked him for pointing out his views. In terms of the question about the Vietnamese fulfilling a long-standing goal, he said that it was a very standardized and reductive view that ignored spatial and temporal variations. As for the second question about the US bombing, he said that people had argued that it might have violated international law and also provoked socioeconomic unrest. He stood by his word that the word yuon could incite hatred and should be understood as an incitement to genocide in the context of Democratic Kampuchea.

The President adjourned the hearing. Court will resume Monday, March 20 2016, at 9 am with the testimony of 2-TCW-900 via audiovisual link in relation to Au Kanseng Security Center, after hearing oral responses to the request by the OCP to summon an additional witness. The president then thanked the expert, wished him a safe trip home and dismissed him.

[1] E3/1593, at 01149979 (EN).

[2] E3/3995, at 00802832 (FR), 00773767 (EN), 00844612-14 (KH).

[3] E3/221.

[4] At 00386178 (FR), 00000812 (KH), 00182695-96 (EN).

[5] E3/4604, at p. 4, 0519832 (EN), 00064711 (KH), 00520342 (FR).

[6] At 00519834 (EN), 00064714 (KH), 00520345 (FR), at p. 6.

[7] E1/382.1, 26 January 2016.

[8] E3/3346, at 00431528 (EN), p. 86.

[9] E3/4527, at 00661462 (EN), 00830768 (KH), 00792921 (FR).

[10] Page 265.

[11] Page 267, at 00341709 (EN).

[12] E3/8404, at 00419728 (EN), 00716183 (KH), 00017542 (FR).

Featured image: Alexander Hinton (ECCC: Flickr).