Chairman of Highest Council for Islamic Religious Affairs Testifies

Today, April 6 2016, Oknha Sos Kamry – the Chairman of the Highest Council for Islamic Religious Affairs in Cambodia – provided his testimony in relation to the treatment of the Cham, after having refused to appear in front of the Court for the past few days. He cited health reasons for this refusal. Mr. Kamry gave evidence in relation to a document that he claims to have seen, in which a plan was set out to kill all Cham people in Cambodia by 1980.

Cham people in Cambodia

At the beginning of the session, Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn announced that witness 2-TCW-827 would be heard today. All parties were present with Nuon Chea following the hearing from the holding cell. Witness Oknha Sos Kamry alias Kamaruddin Yusof was born in 1950 in Akmok, Speu, Cheyyau, Chamkar Leu, Kampong Cham and currently resides in Phnom Penh. He is the director of the Supreme Islamic Center.

He said that he would tell the Chamber the truth before the President informed him about his rights and obligations.

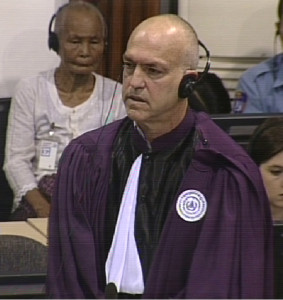

The floor was granted to International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian, who started his line of questioning by inquiring how he identified himself ethnically. He replied that he was Cham. Mr. Koumjian then wanted to know whether all those people who were Muslim in Cambodia identified themselves as Cham or whether there were other ethnic minorities in the 1970s. At this point, Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe objected, arguing that the witness was not in the position to answer this question. Mr. Koumjian replied that the witness was the president of the Islamic Association and that he lived and practiced in the 1970s. He replied that Cham people could live in Cambodia and could be Cambodians. Mr. Koumjian rephrased and asked whether he had heard of the chvea, which the witness confirmed. He did not know the details about their historical background. They practice the Islamic religion. He confirmed having heard of the term Islamic Khmer. He said that “we considered us as part of the Cambodian society” while also practicing Islam. They had the freedom to live dispersed amongst the Cambodian people. He did not know where the chvea lived at the time, since he had been pretty young.

Mr. Koumjian turned to the next question and wanted to know whether he lived in Akmok Village or Akmok Speu village. Mr. Kamry replied that it was the same village. He studied the Islamic religion in Akmok. The Khmer Rouge entered Akmok Village prior to 1975. After the day of the coup d’état he did not go to school anymore, since this was not allowed anymore. He was teaching Cham children when the Khmer Rouge arrived. He taught them both religion and Khmer literature.

Almost all villagers living in Akmok worked in the rice field. He was not allowed to continue teaching during the Khmer Rouge, but people were allowed to study the Khmer literature. Religious training was banned after the fall of Phnom Penh, Mr. Kamry said. They had to eat communally after 17 April 1975 “and we were not allowed to continue our religious practice”. After the village was under the control of the Khmer Rouge, they were not allowed to wear their customary clothing but had to wear the same clothing provided by the Khmer Rouge. They were not allowed to speak their Cham language openly anymore, but could speak it to each other “when we were not observed”. All religious practices were prohibited. They could speak to each other in the open where they worked “since we worked mixed with the Khmer people.” Besides the work place, the Cham people “could not gather in large numbers”.

Teaching

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

After the arrival of the Khmer Rouge, he was allowed to continue teaching Khmer literature. There was no clear instruction for teaching, since his teaching was not formal. He received some teaching material. He taught children how to read. There were no specific hours set out for the children to teach. At this point, Mr. Koppe interjected and said that he had an observation that related to something that was 25 minutes late. He asked whether there was a reason why the witness had not given an oath and whether that meant that he gave testimony unsworn, as was the case in his Written Record of Interview. Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn said that there were two possibilities according to Rule 24(1): first, a witness could confirm that he or she would only tell the truth about what he or she knows, and second this could be done according to religious practice. In his Written Record of Interview, he had said that it was not necessary for the religious leaders to take an oath and that he had confirmed telling only the truth. The President asked about the reasons why he had not taken an oath. The witness replied said that they did not have to take an oath. The oath was only used to declare the ownership of property. “And if we cannot recall what we remember fully, it is not necessary to take an oath”. He said that it was against his religion to take an oath when not being able to remember something. The President said that the judges had conferred yesterday and that they adhered to the second possibility of Rule 24(1). Mr. Koppe interjected again and said that the witness did not fit any of the Rule 24(1) options. Mr. Koumjian said that the rule also allowed for the possibility of affirming to tell the truth. He asked the witness to affirm this again, which Mr. Kamry did.

Mr. Koumjian then resumed his line of questioning and asked how many hours per day the children were allowed to study. He answered that there were no specific hours. They had to work when being able to do so. The children he taught were between seven and fifteen years old. Some older children stayed in the school building, while younger children had to stay in a center in which people were looking after them.

Families in the district

There were more than 1,250 families living in the area.

The word “family” were not specifically defined. Some were living together, but it depended on the tradition of the family. On average, there were five to six members, while others had only one or two members. When Mr. Koumjian asked whether all these families lived in Speu throughout the whole Democratic Kampuchea regime, Mr. Koppe objected and said that the witness was not an expert and was 25 years at the time: “He was living his life”. When Mr. Koumjian repeated the question, Mr. Koppe requested a ruling on the issue. The President announced that the objection was overruled. Mr. Kamry said that 20 to 25 percent survived the regime, “and the rest may have been killed”. Some people had been evacuated from the village “and perhaps 50 families were allowed to remain in the village”. Some people were evacuated, including his family. They had no choice.

Fate of Cham people

He “used to see the dead bodies, because the killings were widespread”. He did not know all the burial places. Usually they would be buried where they were killed. Some people were taken away at the worksite, while some people were taken out of the houses. He confirmed that he followed people who were arrested. “And then I noticed that they were killed and buried’. There were some people who secretly practiced the religion at night time, but they were monitored. They would “take measures according to what they had in mind”. They were trying to work, so he did not know for certain what happened to those who were monitored.

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian

There were no religious leaders during the regime, he said. When asked about the fate of religious leaders, he replied that he presumed that the killings did not discriminate against individuals. Twenty to twenty-five percent of the villagers survived, after which they were joined by other people.

He remained living there until the liberation day. A month later, he was evacuated. After the liberation day, between 100 to 200 families survived. Mr. Koumjian asked whether he ever went to Cheyou village. Mr. Kamry replied that he used to live in that village. He lived there for one year, perhaps in 1977. He returned to his previous location in early 1978. He had been afraid that he was not allowed to live in Speu, so he asked for permission to relocate. He thought at the time that if he was not evacuated “it was not good for me and killings started to take place”. This was why he asked for permission to live in another village.

Asked whether he had changed his name, Mr. Kamry said that he used the name Kamry at the time. His other name – Kamaruddin Yusof – was the original Islamic name. In practice, the parents would name their children “in full”. Sometimes, the names would be shortened when ID cards were made. Since he did not want to reveal his Cham identity during the Khmer Rouge regime, he shortened it.

Meetings

Mr. Koumjian inquired whether he remembered attending a meeting in a village called Bos Khnor. He replied that he could not remember this clearly. Mr. Koumjian asked whether he ever attended a meeting in which the Khmer Rouge had talked about a plan related to the Cham. Mr. Kamry said that enemies were discussed in every meeting. There were many ties of enemies under the Khmer Rouge: former officials of the previous regime, religious leaders, Cham people, and more. They did not specifically refer to Cham people, but to Islamic followers. To refresh the witness’s memory, Mr. Koumjian read an excerpt of a book in which he had talked about a meeting which the Khmer Rouge had said that Cham people were the biggest enemy and had to be destroyed by 1980.[1] At this point, Mr. Koppe objected and said that it was leading. The President announced that the objection was overruled. He said that he remembered this meeting. During the first meeting at Bos Khnor, they first did not mention specific categories. However, this was explained at a later stage in a meeting in Bos Khnor.

Mr. Koumjian wanted to know whether he knew someone called Ban Siek alias Hor alias Ho. He denied this. At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

A document about a plan to kill the Cham

After the break, Mr. Koumjian read out the statement of Ban Siek, who had mentioned a person called Sou Soeun.[2] The witness did not know this person. He had heard of Ke Pauk, but did not know his wife. Mr. Koumjian said that Ban Siek had said that the district security office was located in Bos Khnor.[3] He asked whether he knew where the security office was, which the witness denied. The meeting that he attended was held close to a pond in an open field. Mr. Koumjian then inquired whether he had seen any written documents about plans that the Khmer Rouge had. He replied that he saw a document that said that the Cham were enemies. Whenever the quarter chief was absent, Mr. Kamry asked the messenger to find documents for him so that he could read them. He did not have the intention to read the documents. A twelve year child had brought him a book to read. He did not recall the color of the book.

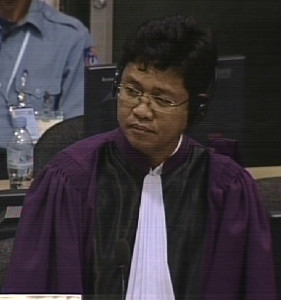

Seng Leang asked whether female Cham were allowed to wear their hair long, which the witness denied. They had to cut their hair short. There was a mosque during the Khmer Rouge time, but only the roof remained supported by the frame. They used that mosque for example for a dining hall. The Holy Books had been destroyed. Some Cham people burned their Holy Books. Before 1975, there were religious leaders in every village. In his village, they had to comply with the instructions.

National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Seng Leang

Moving to his next topic, Mr. Leang asked about the arrest of people and dead people that he had claimed to have seen. Mr. Kamry confirmed that he saw the pits where dead bodies were buried. He did not witness how villagers were tied up and arrested, but saw that they were called out and disappeared since then. Sometime, they happened at night time, and sometimes at night time. During 1977, arrests happened “on a massive scale”. The pits were close to a village. The pit was a well at the outskirt of the village.

Mr. Leang inquired whether he knew a location called Tapum, which the witness confirmed. It was located to the southeast of the national road. He had heard that people were taken to the plantation farm and killed.

He was prohibited from teaching in early 1978. He confirmed that he was assigned to find firewood one time. He went around in the forest to find it. There, he saw pits with dead bodies. He did not witness the actual killings. There were many pits in the forest.

Mr. Leang asked whether he knew the pagoda called Por Pring, which the witness confirmed. He used to collect firewood around there and saw an abandoned security center. He saw shackles and “could draw a conclusion that the location was a detention center”.

Turning back to the pits, Mr. Leang wanted to know what he saw in there. Mr. Kamry replied that he was scared and did not pay close attention.

As for the book that he had seen, he replied that he could not remember the content of it. He could remember that it was thin.

Next, Mr. Leang wanted to know whether it was correct that people were evacuated in 1975. He could not recall the exact year – it may have happened in late 1974 or early 1975. He said that he did not know the reasons for the evacuation. He did not know why the fifty families, including his, were allowed to stay in the village while the others were evacuated. At this point, Mr. Leang finished his line of questioning and the floor was handed to the Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers.

Religious practices

National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang asked what the importance of religion was to Cham people. He answered that he needed to adhere to the disciplines of the religion so that he could lead the followers. He confirmed that there was a prohibition to practice their religion. There were meetings held to tell them about the abolishment of the religion. In relation to the meetings, they happened rather frequently. During these meetings, they were informed about the ban.

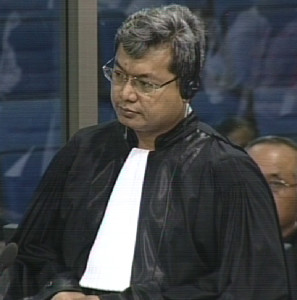

National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang

Mr. Ang then wanted to know whether there was a structure in religious leadership before 1975.The witness confirmed this and said that they had freedom to practice their religion before 1975. The religious leader in a village is a hakim, and above him a mufti. He did not know about the fate of last mufti in the Sihanouk reign, and had only seen his photo in a museum.

After the liberation day of 1979, people tried to return to their native villages. These villagers initiated the building of a mosque and there had not been a national leadership level at the time yet. After the liberation day, there was no clear communication between each leader. The structures were established in various villages. The national leadership was only established in 1993.The difficulty was how and where to build mosques, since 80 to 90 percent of them were ruined and had to be rebuilt. Most of the mosques were dismantled. Their wood was used for other purposes and they were destroyed if they were made of concrete. He did not know about the destruction of mosques were nationwide. He confirmed that the destruction of mosques took place between 1975 and 1979.

The religious leaders were not distinguished from other people, he said. “I conclude that their status was considered of that of ordinary people”.

The food regime was the second discipline after the respect of the religious practices. However, during the Khmer Rouge regime they had to eat “what was given” in order to survive. Pork was also given to them. He said that the ban of their religious practices had an impact on them, but they tried to practice their religion secretly.

He taught the alphabet to children. He did not teach much else and would lead them to work. This prompted Mr. Ang to refer to a statement he had given to DC-Cam.[4] At this point, Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel interjected and said that this statement had not been admitted yet and an 87(4) motion should be made. Mr. Koumjian said that this was correct and that they would made the 87 (4) motion. Since no party objected, the document was admitted.

Mr. Ang referred back to the statement, in which he had said that he taught children also about activities of the revolution. Mr. Kamry said that he could not recall this clearly. He taught the children informally.

Moving to his next topic, Mr. Ang wanted to know whether he knew anything about marriage during the Khmer Rouge. He replied that he saw marriage ceremonies taking place from time to time, but that he had been married before the Khmer Rouge. He did not know who was involved in the marriage. He could not recall the commitments the couples had to make in detail, but remembered that they had to commit to loving each other and following the revolution. He continued living with his wife, but his wife was an ordinary villager then. While he was in the village, all children were Cham. However, all children were Khmer when he left. He left the village in early 1977 and returned in early 1978. There were teachers from elsewhere who taught the Cham people. After he left the village, there was a replacement teacher who taught the Cham people. He left the village alone and his wife continued working in the village. Of the more than 1,000 families in his village, only around 15 to 20 percent survived, Mr. Kamry said. About thirty percent of his relatives disappeared, but more people disappeared on his wife’s side. His younger sibling and various cousins died. His younger sibling was called Fatymas.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for the lunch break.

Functions of the witness

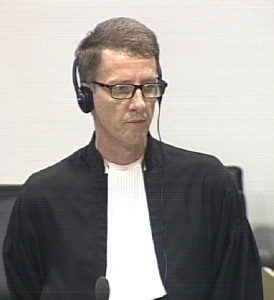

After the break, the President announced that the witness could indicate if his health issue required to do so and they would take a short break. If they had to adjourn earlier, this meant that the witness would have to come back tomorrow morning. The floor was granted to the Nuon Chea Defense Team. Defense Counsel Victor Koppe asked him whether it was correct that he was the chairman of highest Council of Islamic and Religious affairs, which the witness confirmed. He was assigned by a royal decree to be in charge of the Islamic disciplines. Asked for the purpose of this council, he said that every country had religious leaders. The main task was to provide and guarantee disciplines to the Islamic religion and also solve issues that arose out of the Islamic community. They also existed before 1975 and now worked in Cambodia. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was a fair summary that he was one of the highest Islamic leaders in the country, which the witness confirmed. He said that he was also the chairman of other Islamic leaders in Cambodia. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that he was the chairman of the Cambodia Islamic Center. He answered that the Royal Government of Cambodia had assigned him to be in task of this center that was in charge of providing religious trainings to Islamic followers in Cambodia. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he was one of the highest authorities for the interpretation of Islamic writings and the Qur’an. He replied that his role was to disseminate the content of the book.

He was not sure about the Islamic population of Cham people in Cambodia, but he estimated that there might be 500,000 to 600,000 Cham people in Cambodia.

Refusal to testify

Mr. Koppe then wanted to know whether it was correct that he had not wanted to testify in the beginning. He answered that this was because of his health issue “as far as everyone is concerned”. He confirmed that this was the only reason.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he was aware of a letter by the Council for Islamic Affairs that forcing his appearance would lead to violence and protests in Cham. “It is necessary that there should be a protest”, Mr. Kamry said. When Mr. Koppe asked why it would lead to violence, he replied that the only reason he refused to appear was due to his health. He confirmed that he had refused to be examined by the court medical staff. He said that he was aware of his health issues more than anyone else and that any additional check was unnecessary.

Mr. Koppe asked who his Excellency Osman, Advisor to Hun Sen was. He replied that he should only ask questions that related to himself and not issues of other people. Mr. Koppe directl asked whether Osman Hassan had asked whether it was possible to replace Mr. Kamry with another person. Mr. Kamry replied that he only refused to appear because of his health. Mr. Koppe pressed on and referred to his Written Record of Interview, in which he had said that he did not have to take an oath before speaking due to his role as a religious leader and due to religious practices.[5] Mr. Kamry replied that he had answered the question already. There were two possibilities: They may overstate or may not tell everything in detail. Since he believed in religion, he asked not to take an oath. In his religion, it was not absolutely required to take an oath. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether a witness could only be considered to be under oath when affirming that they would tell only the truth in the name of Allah. Mr. Kamry said that it was not required to take an oath and that this belonged to the Islamic freedom.

Statistics

Moving on, Mr. Koppe wanted to know how he reached the number of 300,000 Cham living in Cambodia after 1979. Mr. Kamry said that it was an estimate and that this was why he had not wanted to take an oath. Mr. Koppe asked whether he was aware of the figure of 182,000 Cham people living in Cambodia in 1982 that a census had shown. Mr. Kamry answered that he did not know. Mr. Koppe asked how he reached the conclusion that 700,000 Cham people lived in Cambodia before 1975. The witness answered that this was also an estimate. Since they did not have any specific basis to rely on, people came to different conclusions. Estimates ranged from 400,000 onwards. Mr. Koppe queried whether he was aware of estimates from foreign scholars that were dramatically lower than the estimate he had given. Mr. Kamry said that this was not true.

Mr. Koppe asked whether he could explain that an American scholar estimated that 190,000 Cham were living in Cambodia in 1975 and that the Australian scholar Kiernan had put the number to be 250,000.[6] The witness did not know about this. The witness said that Tboung Khmum had one village that consisted of 1,000 families. Moreover, there were three villages Prachhes, Trea and another. He said that “if we do the calculation all together, … I believe that the population of the Cham people is high”. If adding all these numbers together, there were perhaps 1,000,000 Cham people living in Cambodia.

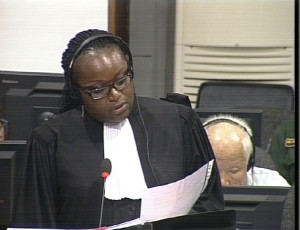

Witness Sos Kamry

Mr. Koppe said that Vickery had said that 10,710 Cham people lived in Cambodia in 1979 and Kiernan had estimated this number to 77,000, while the witness gave an estimate of 400,000. Mr. Koppe was instructed by Judge Claudia Fenz to give references, which he did.[7] Mr. Kamry said that 50 percent of Cham people may have died based on his estimates and his actual observation. “We cannot go to one individual to ask specifically about that issue”. The regime lasted for almost four years, he said, and the birth rate was also high after that period. The death toll may have been high.

Mr. Koppe inquired how he had reached the number of 300,000 Cham people. He replied that he went to most of the villages and was invited to attend many meetings as a religious leader to disseminate the Islamic content. He said that he went to 70-80 percent of the villages throughout the country and that this was how he reached the number.

Mr. Koppe asked when the meeting took place in which the fate of Cham people was discussed. In one statement he had indicate November 1978, in another early 1978 and in another late 1977. He answered that he attended several meetings and that this was why he could not recall details. He replied that he could not recall whether they took place in early 1977 or late 1977. It had to be before this, though, since he had moved to another place throughout 1978.

The Plan for Progressive Cooperatives

Mr. Koppe then wanted to know whether he knew Mat Ly. He answered that he heard of his name only after the liberation day and did not know him during the Khmer Rouge regime. After 1979, “I rather frequently met with him”. The nature of their conversations was “rather casual” and they did not talk about any specific topics. He had never heard of the name Ouk Bunchhoeun. Thus, he did not know what his function was in the East Zone in 1978. The witness replied that it was prohibited to walk freely throughout the regime.

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Mr. Koppe asked what he remembered about the booklet called The Plan for Progressive Cooperatives that he had seen. Mr. Kamry replied that they wanted to measure land. When he arrived in the area, only the messenger and not the chief was there. Thus, he asked the messenger whether he had any book to pass the time. He was given the book that discussed the situation of the enemy. Mr. Koppe referred to his interview, in which he had said that the book was light-yellow and had only 16 pages.[8] Mr. Kamry recounted that he only read the section on the enemy situation in relation to the Cham. Asked how he could remember that it had 16b pages, he said that it was a light book. Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that he had said to the investigators and Ysa Osman that he read that the “Cham is the biggest enemy that must be totally smashed before 1980.” He replied that he could not remember the exact year, but that all Cham must be smashed. He did not know whether the authors of the book exaggerated, but he was scared. He received a whole stack of books and not only this book.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether this pile of books was secret, since he had been given the books to just pass some time. He answered that he did not know the nature of the books. The messenger got the books from his superior’s office. He denied having ever spoken to Mat Ly about the existence of this book. He “used to speak casually with my friends” about this book.

When Mr. Koppe asked whether he had an explanation why he was the only person who knew about the existence of the book, Mr. Koumjian observed that several witnesses had talked about this and Kiernan had talked about two sources that saw such a document. Mr. Koppe said that this was not correct but rephrased. He asked why the highest ranking person Mat Ly did not talk about such a document. Judge Fenz said that this led to speculation. Mr. Koppe rephrased and confronted the witness: “Is it not true that you never saw such a book and that you never saw the sentence” that the biggest enemy are the Cham? He replied that he did not know more about this and that he had not known Mat Ly at the time. Mr. Koppe pressed on and said “please do not be offended”, when asking whether this particular answer was the reason why he did not want to take an oath. Mr. Kamry denied this.

Mr. Koppe moved on and asked whether his understanding was correct that there was no specific reference made to the Cham during the meeting. He replied that the situation of the enemy was discussed in every meeting. He had taken his personal conclusion that more Cham people had been killed. Seventy to eighty percent of the Cham had been evacuated from their native villages. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he was still a teacher at the time that he said to have attended the meeting and read the booklet. He replied that he was reassigned to return to his village after having attended the meeting. As for the book, he believed that he read it in October 1978, which was a different time period.

Mr. Koppe asked whether his account had changed from late 1977 to October 1978. The witness said that he did not understand the question. Mr. Koppe said that twenty minutes ago he had told the court that he was at the meeting and saw the book in late 1977. He answered that he saw the book in late 1978 after having returned to his village in early 1978. In relation to religious affairs, he stopped teaching in 1975, since it was prohibited since then. This prompted Mr. Koppe to read an excerpt of the DC-Cam statement, in which he had said that he continued teaching in late 1977 despite the expiration of his mandate.[9] Mr. Koumjian interjected and said that the witness had consistently stated that he continued teaching Khmer children but stopped teaching religion. The witness told the court that he had to stop teaching religion in 1975. When being in the other village, he could only teach Khmer literature. Mr. Koppe asked how he could conceal that he had been teaching religious matters beforehand. He repeated that he had stopped teaching religion in 1975. He went to Cheyou in early 1978. Mr. Koppe inquired whether it was correct that it was unknown to the village chief that he had taught religion beforehand when seeing the booklet. He said that he was assigned to transport fire wood to the office in 1978. In late 1978, he was assigned to measure land in other villages, which was the time that he happened to see the booklet. Asked whether he used other means to conceal his identity other than changing his name, Mr. Kamry recounted that there was no longer any research into the background from the villagers until 1978 when he was assigned to measure land. The local people still recognized him as a Cham person.

Turning to another topic, Mr. Koppe sought information about the rebellion in Svay Khleang and Koh Phal.[10] The witness answered that he had heard about it only later and that he did not want to talk about this, since he did not know any details. Mr. Koppe said that he had told the investigators that this rebellion was violently crashed. He answered that he had told them what other people had told him. Neither did he know who was responsible for it, nor had he heard of the involvement of any current government officials.

At this point, Mr. Koppe handed the floor to his national colleague Liv Sovanna. Chamkar Leu was around four kilometers away from his village. Only around 50 families lived there. He was one of the last couple who got married in a religious ceremony. Mr. Sovanna asked whether there was a ban that Cham people could not marry Cham but only Khmer people, which the witness denied. He did not know whether this was applicable in offices as well.

Clarifications

Next, Mr. Sovanna wanted to know whether there was any discrimination in the training that he provided to the Cham people. He answered that the children that he taught received the same education. The children at Cheyou “loved me more” than the Cham children. When he went to Cheyou, he had two daughters. He could visit his house once in a fortnight or every ten days. His wife and daughters remained living in Speu. Mr. Sovanna wanted to know whether the fifty Cham families that were not evacuated remained living in Speu until the end of the regime. He answered that the evacuation of the Cham people was before 1975 and between thirty and forty families were sent to live in that village. Later on, some families had been killed. “No one knows that reason for the killing. Because of that, everyone was afraid of being killed. So those people were waiting and … hoped that their life would be spared. We lived very fearfully.”

National Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Liv Sovanna

Mr. Sovanna wanted to know what the ethnicity was of the chief of Speu Village. He replied that the leaders were mostly Cham after the evacuation. Later on, most of them “met very unfortunate fate” and were almost killed. After the killings, “new faces had been replaced”. The new people were Cham. However, there were two others who came to monitor the new leaders. Later on, they were also killed. Mr. Sovanna asked whether there were purges in his village or not and whether this was the reason that Cham people could survive. He replied that evacuations took place before the fall of Phnom Penh. Killings at Speu happened at a later stage. He did not know whether there was a plan to purge entire Cham villages. In 1978, the killing stopped. Around five months later, the liberation took place. At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

After the break, Mr. Sovanna inquired whether he knew who appointed the village chief of Speu Village, which the witness denied. Next, Mr. Sovanna wanted to know the difference between the Cham people and the religious followers that he had mentioned in the morning. Mr. Kamry said that also Buddhists would be killed. Mr. Sovanna inquired whether it was correct that Cham people who forfeited their religion would not be killed, which the witness denied. He said that other religious followers, including Buddhists, would also be killed. His younger sibling was evacuated to Trapeang Russei Village. Most of the villagers, including his sibling, were sent away and killed. After 1979, only around twenty percent returned to live in the village. One day, he met with elderly men who lived in Speu Village and asked for headcounts. They counted 1250,000 families. There were only 144 families from that village. Mr. Sovanna referred to his statement, in which he had said that 14 families of the 50 families were killed.[11] The witness confirmed this and said that this only referred to one village. Some Cham people were sent to the plantation and were taken away together with the people at the plantation. Turning to his last question, Mr. Sovanna wanted to know whether he could tell the Chamber, in his position as the President of the Council for Islamic Religious Affairs in Cambodia, whether the rate of the disappearance of the Cham people was similar to the one in Chamkar Leu. He replied that it was higher in the lower part than in the higher part. People who lived along the riverbank lived on the land and not on the river. Some people remained. The disappearance of the people who lived next to the riverbank was similar there. The disappearance rate was lower at the border.

The floor was granted to Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé. She asked whether she had understood his testimony correctly that he went to Cheyou Village at some point, which the witness confirmed. He had made the request to leave Speu Village to the commune director from the village, who was the head of teaching and who was also from Cheyou Village. He could not remember the name of this director. He could not recall the duration of the term that the director held his function. Mr. Kamry confirmed that he was the one who made the request. He had made the request to go to Cheyou specifically. It was around four to five kilometers away from Leu Village. Ms. Guissé referred to one of his interviews and asked whether he agreed that he only lived in Leu and Cheyou during Democratic Kampuchea. Ms. Guissé referred to his statement, in which he had said that he was expelled from Leu Village and sent to live in another village.[12] She wanted to know whether he requested to leave Leu or whether he was expelled. If taking a shortcut it was three to four kilometers, and when taking the longer way it was four to five kilometers. He said that he had requested this transfer himself to refashion himself. He rejected her allegation that this contradicted the statement and said that if he requested to leave the village and did so, this meant that he was expelled.

As for the shortening of his names, he said that children would usually use aliases and use these also for their identity cards. When he started teaching, he made people refer to him as Sos Kamry. At this point, national Co-Prosecutor observed that the Khmer version of his statement did not use the word “expelled”.[13] Ms. Guissé asked whether it was correct that he started using the name Sos Kamry when he started teaching, which the witness confirmed. He said that he started teaching in 1973. Ms. Guissé referred to his OCIJ interview, in which he had said that he started using this alias when he was in Cheyou.[14] He replied that the person who had taken his statement might have made a statement. “Of course I was scared, because people were taken away and killed”, which was why he had to relocate. He maintained his position that he used this alias since he started teaching.

Meeting and document

He confirmed that he continued teaching when being located to Cheyou. He returned to Leu in early 1978 and lived together with his wife. He confirmed that the villagers knew that he was Cham. He also confirmed that there were other Cham villagers. He was assigned to go and collect something for three or four months when he was at Bos Khnor. It was adjacent to Ta Aung. He was assigned to get children to collect worms out of the cotton plants. There were many meetings, but the specific meeting they had talked about was perhaps in late 1977. Ms. Guissé referred to his interview, in which he had said that the meeting took place in 1977 and that he saw the next day after the meeting.[15] He replied that the document he mentioned was at a different time than of the meeting and around one year apart. She asked whether there was therefore a mistake in the book that indicated that he saw the book the next day. He answered that it may have been in September or October 1978 that he saw the book. He confirmed that Ysa Osman only mentioned 1977, whereas it should have been two dates: 1977 and 1978. He also confirmed that they made general statements about enemies in the meeting, but said that they mentioned different types of enemies, including Cham and reactionary people.

International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

He was given the document in the commune office of the Au Nheung Commune, which is in Speu Commune nowadays. He did not remember the name of the commune chief at the time. His colleague Kro At from at the time is already deceased today. The office was not a proper house, but more a hut. His colleagues may not have seen the document, since they were outside. He did no remember who was with him in the office and who was outside. When he asked for the documents, they were all together in the office. He did not know whether some of his colleagues went outside or whether others took some documents to read. Ms. Guissé asked whether it was not correct that he was alone with the messenger when he received the documents. He replied that the messenger was the only person in the office. After handing over the documents to them, the young messenger went to look for oranges. He was with his other colleagues, but could not remember whether they were sitting on chairs or outside of the office. He could not recall well the names, since it had happened a long time ago. He did not remember who he was talking to when returning to Leu. She asked whether it was correct that he had not warned the other Cham people when returning to Leu. He replied that several years after the liberation, he lived in Speu Village for twenty days, before moving to a location near the border. Twenty years later, he came back. At this point, Ms. Guissé handed the floor to her national colleague Kong Sam Onn.

Back to statistics

Mr. Sam Onn asked how many Cham villages were in Chamkar Leu District. He answered that there were two villages. One was Speu and to the south was another Cham Village. There was also Cheyou, which was a bigger village compared to the others. There was also Au Trau Village (or Au Pes) next to the river. Currently, there were around 100 families in Au Pes, but at the time there were only fifty families.[16] He counted small and big villages and came to the conclusion that there were around 250 Cham villages. He used to live in Speu, Trapeang Chhouk, Kampong Thom, Battambang and other locations. Overall, there were more than 250 villages, he repeated. In 1993, when the Ministry of Religion selected religious leaders, the ministry invited hakims and religious leaders to vote. Religious leaders from 210 Cham villages came to attend the vote. The others did not come to attend the vote. He asked which village consisted of a small number of Cham people. Mr. Kamry replied that there were no Cham villages in Kampong Thom and Dambe, only few in Kratie and not in Kampot in 1975. Afterwards, Cham villages increased. Provinces that had large numbers of Cham people was Kampong Cham. Before this, there were around 30 Cham villages in Tboung Khmum, while there were now around 100 village in Kampong Cham. He said that there are around 2,000 families of Cham people in some villages. When adding up the number of Cham people, “we can say that there are many Cham people” living in Cambodia. Before 1975, there were around 220 Cham villages. One village might have 705 to 750 Cham families, while other villages had more Cham families.

He did not work on statistics before 1975, so he did not know how many Cham families lived in one village on average. Turning to his last set of question, Mr. Sam Onn wanted to know how many villages there were in Cambodia in 1975 including Khmer villages, which the witness did not know. Neither did he know how many villages there were in total in Cambodia at the moment.

The President thanked the witness for his testimony and dismissed him. The President adjourned the hearing. It will continue tomorrow, on Thursday, April 7 at 9 am with the testimony of 2-TCW-1011 in relation to the Security Center Phnom Kraol.

[1] E3/2653, at 00904362-63 (KH), 00943975 (FR), p. 116 (EN).

[2] E3/9517, Statement of Ban Siek, at answer 10.

[3] E3/9516, at 0800955 (KH), 00841971 (FR), 00841966 (EN).

[4] D176/3.43, at 00230610 (KH), 00122208 (EN), 0022019 (number missing in translation, FR).

[5] E3/6216, at 00225495 (EN), 00223891 (KH), 00234568 (FR).

[6] E3/9382 and E3/9701 Article by Ysa Osman in Phnom Penh Post.

[7] E3/9701, 10 March 2006, at 01199557-58 (EN), 00126400-01 (KH).

[8] 00225497 (EN), 00223893 (KH) 00234570-71 (FR).

[9] D175/3.43, at page 5 (EN).

[10] D175/3.43, at page 8 (EN).

[11] E3/5216, at 00223894 (KH), 00234571 (FR), 00225498 (EN).

[12] D175/3.43, at page 4 (EN), 00230603 (KH).

[13] D175/3.43.

[14] E3/5216, at 00234569 (FR), 00225496 (EN), 00223892 (KH).

[15] E3/7690, at 00485382 (FR), 00223899 (EN), 00223896 (KH).

[16] D175/3.43, at 00134612 (KH), 00222009 (EN), 00220621 (FR).

Featured Image: Witness Sos Kamry (ECCC:Flickr).