‘There were never instructions not to kill children, not to kill pregnant women’: Duch Petrifies Courtroom

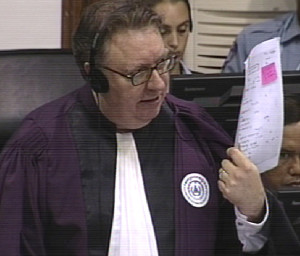

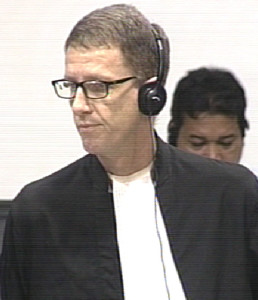

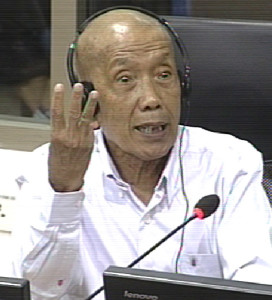

The questioning of Duch continued today, and it was announced that the Civil Party Lawyers would likely take the floor tomorrow afternoon. Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak had the witness to himself for the whole day, and took all the time necessary to obtain crucial details about the functions of Ta Khmao prison, the fate that awaited women, children and other relatives of prisoners when they were brought to S-21 and finally, interrogations methods at S-21. Duch proved to be an attentive and cooperative witness, answering every question with great detail. Even the most sinister matters did not seem to temper his volubility.

Commuting between Ta Khmao prison and S-21

Picking up on yesterday’s questioning, Mr. Lysak asked Duch about Thach Chea’s children and wife, who were killed at S-21, but he could not provide more details about any more medical experiments that took place. Mentioning that Nuon Chea had read in a confession about plans to poison Pol Pot, Duch made the account of the climate of strong suspicion that reigned at S-21, even though prisoners who had technical skills in the former regime were used at S-21[1].

Mr. Lysak set his focus on the role of Ta Khmao prison, and its complementarity with S-21. Duch was read two quotes of his previous testimony: S-21 was used for interrogations, while Ta Khmao was a detention facility[2]. He confirmed this, added that interrogators were trained at S-21 and then interrogated prisoners at Ta Khmao. Khmer Rouge Defense Minister Son Sen told him that at some point, the Ministry of Social Affairs wanted to use that prison.

‘That’s impossible’, I told him. ‘There are too many bodies on the compound.’ We needed to exhume the bodies and [ … ] burn the bones [first].

In his 2009 testimony, Duch had specified three locations where prisoners were killed and buried: Ta Khmao, buildings surrounding Tuol Sleng and the Killing Field of Choeung Ek[3]. Duch could not remember when the site was handed over to the Ministry[4].

The children, spouses and families sent to S-21: women and children first

“What happened to spouses and children of people sent to S-21 accused of being traitors, enemies of the regime?”

“They were treated the same way as the prisoners: they were smashed.”

Once again citing the case of the killing of the wife and children of Thach Chea, Ministry under the Lon Nol regime, Mr. Lysak wanted to know how Duch dealt with children when performing his duties, both while at his first prison in Kampong Speu province, M-13, and as chairman of S-21. Mr. Lysak read an implacable quote from Duch: “When I was at M-13, I tried to keep children alive, but since I couldn’t, I gave into this view of fearing revenge and gave into Son Sen’s notion after that; they called my stance of wanting to spare the children lacking in class anger. After the creation of S-21, I kept on doing it.”[5]

Duch remained evasive when Mr. Lysak asked him whether it was Son Sen himself who ordered the killing of the children[6]. He only said that Son Sen instructed them to have “a firm stand and separate friends from enemies”. Mr. Lysak insisted on the children: what was the reason for the party’s stance to “smash” wives and children?

The party had this saying: ‘an eye for an eye’. That principle was contradictory to the Buddhist principle that ‘revenge can be defeated by non-revenge.’

Duch identified the fear of revenge as the main reason why the party wanted to kill children as well, though he also confirmed that the fact they were unfit for labor, as suggested by a document read by Mr. Lysak, was a factor[7]. Duch – convicted of crimes against humanity – quoting Buddhist principles about non-revenge was more than bizarre. The way he conveyed his thoughts was captivating.

Vorn Vet and Duch, partners in crime?

Shifting his focus to the arrest of the spouses and later killing of the children of Vorn Vet, Duch’s immediate superior, and of former Minister of Industry Cheng Orn, Mr. Lysak inquired as to who had ordered him to do it. “Nuon Chea”, the witness answered. This section went off the track of Mr. Lysak’s focal point (women and children), which he went back to shortly.

After a short break, Mr. Lysak resumed his line of questioning and sought to match names of health workers from OCIJ lists to Duch’s statements[8]. He attempted to identify family members of people identified as “30” and “10”[9] (the Prosecution suggested it might refer to Vorn Vet), but Duch could not provide a substantive answer as to who they were.

Co-Counsel for the Defense of Nuon Chea Mr. Victor Koppe objected to Duch identifying S-21 documents thanks to the post-1979 identification code “TSL”, which refers to Tuol Sleng. The Senior Assistant Prosecutor replied that this objection was “inappropriate”, and Duch interjected to say that he was able to recognize the document thanks to the format. In less than a day, Duch’s incriminating testimony was already promising difficulties for the Defense.

His subordinate position to Vorn Vet made Duch fear he would get arrested as well[10]. He then described how Son Sen instigated fear in his subordinates by “screening facial expressions”.

“When Vorn Vet was arrested, were you afraid? [ … ]

I was so afraid I could not do my work. Despite instructions to smash everyone at S-21, I was so desperate I could not do anything until the Vietnamese came. Every time Angkar [the party] called me to work, my wife trembled, afraid I would get arrested.”

Despite his declarations, it was difficult to imagine Duch being paralyzed by fear, given his rather confident ways and attitudes.

Measurement unit for cruelty at S-21: children

Determined to get a full account of what happened to children at S-21, the Prosecution asked almost rhetorically whether the children who were arrested had done something wrong or because they were related to people who were themselves arrested. Duch attempted to divert the Court from the idea that “children” entailed only young children: he mentioned 30-year old Chan, Suon’s son, who was “punished” by being reassigned after several misconducts. Mr. Lysak camped on his position and insisted on young children, until Duch articulated that children were arrested “because their parents had been arrested.”

Mr. Lysak was trying to prove his point that children were killed before their parents were interrogated. Their parents had not been proved guilty of any treason. He proceeded to ask Duch about the chain of command: who decided whether family members were to be interrogated?[11] Was it Son Sen?[12] Duch did not recall. Trying to show that children were not interrogated because of how young they were, Mr. Lysak listed names, pointing two children aged four and six years old that were to be killed[13]. The President chose this moment to call for a break.

Targeting pregnant women

Though Duch was frail and his shirt hung loose, he was focused and alert. Every time a document was shown to him, he sat straight and studied it very carefully. The Prosecution had him look at a documents listing pregnant women and signed by Huy[14] [15]: what was the purpose of such a list? Mr. Koppe rose once again, objecting to the use of the document given it was not translated as well as to the alleged link between the two pages. Judge Claudia Fenz told Mr. Koppe he should seek assistance from his Khmer colleague – Mr. Koppe seemed like he was biting his tongue. He said that he had received a remark by his Khmer colleague that the names did not match the ones mentioned and repeated everyone should be able to follow with a translation, to which Mr. Lysak answered by listing all the corresponding names of the women from Huy’s list on the OCIJ list[16]. Mr. Koppe, incredulous that Mr. Lysak continued to refer to a document only available in Khmer, hunched up his shoulders and kept his hands up for several minutes.

Mr. Lysak aimed at showing how merciless the regime was regarding executions. He asked why some women described as “nearing full-term pregnancy” were sent from Prey Sar to Choeung Ek to be executed, hinting there might have been a practice according to which people too sick or weak to work sent away for execution. Mr. Lysak’s strategy was very efficient: everyone dreaded Duch’s answer, though he eventually said he did not know.

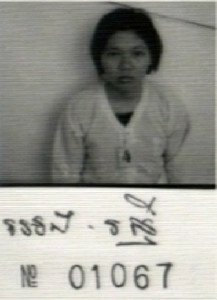

Speaking with photographs

Moving on to more illustrative examples, Mr. Lysak tackled the case of one cadre’s wife and six children being executed[17]. By listing the names of the wife and all the children of this prisoner one by one, and showing the pictures of two of the very young children from S-21, Mr. Lysak struck a chord[18]. The alleged justification for killing children and family members (they held information, they would seek revenge) was contradicted by another document showed by Mr. Lysak: the wife and children of a prisoner were killed before interrogation had been conducted[19].

Faced with a number of documents, Duch repeated that when parents were arrested and killed, their children were too. He accompanied this sentence with a chilling gesture, as if he was pushing aside something with his frail hand.

Hor’s signature was shown authorizing the “smashing” of prisoners for one day, including 160 children[20]. Though Mr. Koppe objected to the translation of the word “smashing”, Duch himself once again struck down the objection by confirming the translation and explained that “kom” was the short form for “komchet”.

Interrogations of S-21 prisoners: “the essence of confession”

“How was it determined who was to be interrogated?”

“I [mostly] assigned prisoners to Pon [Tang Sin Hean] to question those from the upper level, unless the upper echelon asked me to interrogate specific prisoners by myself.”

“How about prisoners from other groups, to what groups were prisoners assigned and how was it decided?”

“For example, I assigned Westerners, to Mam Nai and Pon for interrogation. Mam Nai was the one to interrogate the Vietnamese soldiers and civilians because he spoke Vietnamese.”

“Cold, hot, and chewing”

Relying on three documents, Mr. Lyask asked about interrogation methods (“cold, hot and chewing”) carried out by Duch’s subordinates, including Mam Nai, alias Chan[21]: Duch had said in his 2009 testimony that “interrogation at S-21 took place by what I can call the preliminary interrogation team, to grasp the core essence of the confession and then Hor, with my consultation or alone, would decide to what group they would be sent to.”[22] Wishing to explore the bias of the interrogations, Mr. Lysak asked the witness if the interrogators had access to implicating confessions and other information, which he confirmed. Duch, Hor and Mam Nai, alias Chan, were responsible for keeping the written confessions.

In order to clarify once again the use of the term “chewing”, the Senior Assistant Prosecutor quoted from the testimony Prak Khan gave earlier this year: “beside the chewing unit, there were the cold and hot units. Prisoners interrogated and tortured exhaustively, they were then sent to the documentation. We could “chew” them for more information; only a few cases were sent to my unit”.[23] The witness confirmed the “chewing” was not systematic.

Mr. Lysak examined one last document with the witness, which showed that there were about 30 investigators working at S-21: the witness stated that the numbers changed from time to time, as some interrogators were reassigned or recruited[24].

This concluded the hearing for the day. The Prosecution proved tireless today, and was able to cover specifics related to targeted arrests, interrogations and killings under the regime. Duch’s testimony will resume on June 9th, 2016, at 9 am.

[1] E3/5799, 15/06/2009, 9h31, Duch.

[2] E3/524, 22/04/2009, at 15h28 and E3/5795, 29/04/2009, at 15h24.

[3] E3/5801, 17/06/2009.

[4] E3/524, Duch testimony, 22/04/2009, at 15h49: “Ta Khmao prison existed until May or July, then we organized Chao Ponhea Yat high school [S-21] to keep prisoners”; E3/5794, at 9h48: “Ta Khmao was used until at least June 1996, after which it was transferred to the Ministry of Social Affairs”.

[5] E3/5752, emphasis added.

[6] E3/5758, §2 a).

[7] E3/5805, 25/06/2009, at 9h29.

[8] 14479 OCIJ list, 8097 OCP list: 39 year-old woman, chief of Hospital 75, named Prunh Pal, alias Vin (likely Vorn Vet’s wife).

E3/10256, at 01016798 (KH), 4th prisoner from the top: Yun Khan, alias Poah, 43 year-old female entered S-21 on 21/11/1978, chief of a flower factory and wife of “30”. Sung Brat, son of “30” entered S-21 in 1978, chief hospital in the West zone. 18 year-old girl (page 3), daughter of “A 10” or “10”.

[9] Females who entered S-21 in December 1978, relatives of “10”:

E3/10546, at 01219656 (KH), S-21 biography, TSL 0703: Bi Ken, mother of “A 10”

E3/10546, at 01219657 (KH), S-21 biography, TSL 0704: Prum Po, niece of “10” 17 y/o

E3/10563, at 01219750 (KH), S-21 biography, TSL 3977: Nin, daughter of “10” 6 y/o.

[10] E3/1578, 00178025 (KH), 00194550 (EN), 00178037 (FR), OCIJ interview: “one must understand that there were two categories of suspects, Meng or Von Vet and his family ; subordinates of arrested cadres ; first, sometimes the whole family was arrested, like Vorn Vet, sometimes surveillance was enough. Second category, surveillance.”

[11] E3/2047, document from Huy.

[12] OCIJ interview E3/1576, at 00159564-65 (KH), 00160723 (EN), 00159585 (FR).

[13] OCIJ list, n°3338, 3342, 3345, 3347, 3353-57, 3360. 7/04/1977.

[14] E3/2047, page 2.

[15] E3/1506, 01019382-9383.

[16] N°1 on Huy’s list: OCIJ 3339; n°2 is 3343; n°3, 3351; n°4 is 3359; n°5 is 3362; n°6 is 3340; n°7 is 3361; n°8 is 3349, n°10 is 3348; n°11 is 3341. The only pregnant woman on Huy’s list that we did not find on S-21 list is n°9.

[17] E3/3187, 00008758-59 (KH), 00874194-96 (EN). (Tok Seng Eng)

[18] Photograph: E3/8639.1064. E3/8639.283 E3/94.1, p01223708-09; photo n°120 in the new collection of S-21 photos.

[19] E3/2285, at 00009083-85 (KH), 00873172 (EN).

[20] E3/2133.

[21] E3/8368; E3/834; E3/833, at 00077895 (KH), 00184607 (EN).

[22] E3/5800, 16/06/2009, 9h56-59.

[23] 28/04/2016, 10h41.

[24] E3/1170, at 00443015 (KH), 00602543 (EN), 00544894 (FR). Mam Nai’s handwriting at 00443016 (KH), 00602544 (EN) (chart of the northwest zone army).