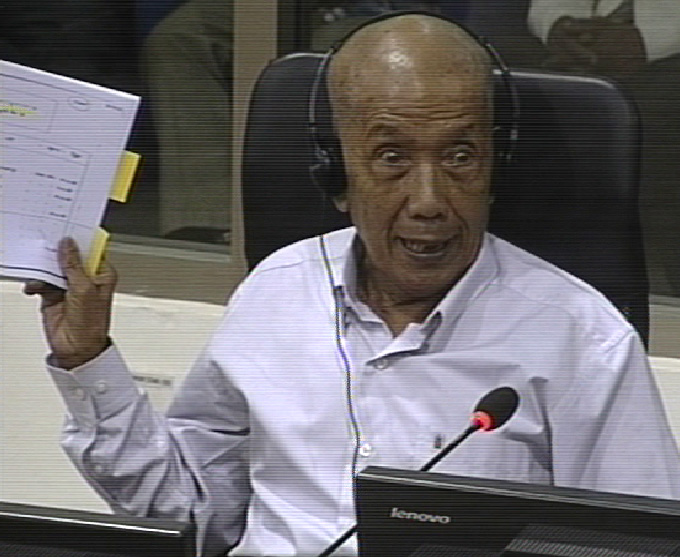

Witness Unravels Chain of Command under Khmer Rouge Regime

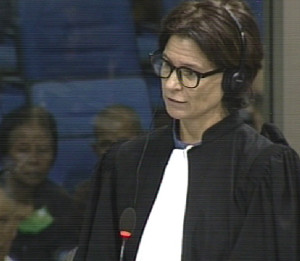

The fourth day of former head of S-21 prison Duch’s testimony continued to attract interest: the usual group of pupils was replaced by about 300 villagers from Kampong Thom, who came to watch today’s hearing. International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Ms. Marie Guiraud’s questioning revealed the limited extent of the witness’ knowledge concerning sexual assault at S-21. Mr. Pich Ang, National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer, went deeper into detail about torture methods before handing the floor over to Mr. Dale Lysak, Deputy Co-Counsel for the Prosecution. Mr. Lysak picked up where he left off last week and strived to obtain more detail on the chain of command the witness was part of.

Sexual abuse and rape at S-21 : Civil Parties persevere

Ms. Guiraud was able to ask more questions to the witness regarding the case he mentioned he knew about[1]. The witness confirmed he knew a few details about Dim Sarung, his professor who was raped at the prison. Her husband was named Keo Kim Huot (phonetics) and was Duch’s teacher as well. Ms. Guiraud was able to refer to her name on a list from the women’s section at S-21, which Duch recognized on the document[2]. He recalled the event as Hor coming to see him and telling him a guard had molested her by putting a stick in her vagina. Duch said he was angry about it and had asked for the guard (whose name he could not remember) to be removed from the women’s section, but could not have him arrested as it was under “Khieu’s” (Son Sen) prerogative, not his.

However, Duch told the Court that he had required all cadres at S-21 who were married to have their wives interrogate female prisoners, and cited Pon’s and Huy’s wives as examples. Answering Ms. Guiraud, the witness said the female interrogators stayed until the Vietnamese troops arrived, but Prak Khan’s 2009 testimony, as well as Lach Mean’s from earlier this year, asserted otherwise[3] [4]. Duch denied it and put into question the reliability of both witnesses.

Revolutionary Moral Precepts

Asked about the moral principles of the party, the witness listed several before Ms. Guiraud asked him to explain the value and the purpose of the 12 Revolutionary Principles.

“They are based on the party’s class”, Duch said.

The Civil Party Lawyer then asked him about principle number 6, which states: “do not behave in a way that violates females”, but the witness did not have anything substantial to say, except that he abided by the precept and never interrogated a female prisoner. Duch was then confronted to a 1978 issue of the Revolutionary Youth newspaper, which contained an explanation for principle number 6[5] and mentioned the need for the community and the party’s approval in order to marry two people. Ms. Guiraud asked:

“Mr. Witness, does this mean that a female-male relationship had to get the party’s approval? Is that the meaning of principle 6?”

Duch answered positively, rubbing his now bald head. When Ms. Guiraud then tackled non-consensual sexual relations between unmarried couples, the witness explained that to the party, engaging in such a conduct was “immoral” and that individuals (both the man and the woman) would be smashed or in rare cases, married. Duch still insisted that there were no cases of rape at S-21. The witness was very engaged and gave details in an animated way. His answers were subsequent enough that Ms. Guiraud did not insist on the same aspects for very long.

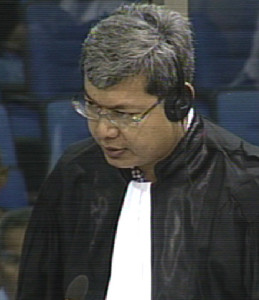

Civil Party Lawyer: methods of torture at S-21

Mr. Pich Ang, National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer, then initiated his inquiry and focused on detainees at S-21 and what methods of torture were inflicted on them. Though Mr. Lysak from the Prosecution covered this extensively, Pich Ang had in mind a different set of questions. He first relied on Chum Mey’s testimony from earlier this year[6] to ask Duch if he knew about other methods of torture inflicted to prisoners, notably breaking the fingers, pulling out the toenails, placing electric wires in their ears to electrocute them and having them lick their own feces off the floor. The witness denied these were consistent practices and disputed the veracity of Chum Mey’s testimony, as he said “nothing happened to Chum Mey’s toenails.”

Before the President announced a break, Mr. Pich Ang asked one last question:

“Mr. Witness, were detainees informed about their right to free speech or their right to counsel?”

“No.”

Children at S-21

This theme had been addressed before, but Mr. Pich Ang went into new details. Duch was confronted with some his previous declarations[7] and gave the Court his take on raising children in the prison:

“The children were given rice to eat but no sentiment.”

He also recalled food shortages that led to some children dying of malnutrition. He then repeated that the children of those being arrested had to be smashed too, confirming the grimly famous slogan:

“When digging grass, the roots need to be taken out”.

Duch said that some prisoners “exaggerated” the small size of the food rations. He was categorical: “if we had had reduced food rations provided to the prisoner, many of them would have died and the confessions be cut off.”

Chain of command

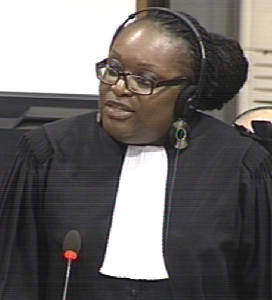

Mr. Pich Ang then attempted to question the witness about another document, which mentioned the “right to smash within and outside the ranks” and the “absolute implementation of our revolution”[8]. Mr. Victor Koppe, Co-Counsel for the Defense of Nuon Chea, objected to this question, as the witness had already signaled that he had no knowledge about it before 1979. The National Co-Lawyer for the Civil Parties reformulated his question but Ms. Anta Guissé, Co-Counsel for the Defense of Khieu Samphan, objected a second time, supporting her colleague Mr. Koppe. She argued that questions should be curtailed to documents related to S-21. The document in question was related to the Central Committee and Ms. Guissé argued that the witness was being asked to speculate on it. The Judges convened to determine whether the objection was to be sustained, and eventually overruled it.

The Co-Lawyer for Civil Parties then went on to ask Duch about the implementation of the revolution through the Standing Committee (or Central Committee), still in reference to this same document. The witness assessed that in terms of implementation, he was repeatedly instructed not to make arbitrary arrests. According to him, Brother Mok (Deputy of the Southwest zone), Brother Si (Secretary of the Southwest zone), Hut Hei, alias Pao (Secretary of Sector 32), Brother Vorn (Central Zone) were members of the Central Committee, which had this authority.

Mr. Ang then quoted the document: “surrounding the center office, everything had to be decided by the central office committee; regarding the Independent Sector, decisions had to be made by the Standing Committee and center military [matters] had to be decided by the general staff.” Duch confirmed the general idea of this chain of command, but specified that the surrounding offices of the center office were made by the political bureau; regarding the center military, Son Sen and Pin were the ones who decided on arrests. The ‘Phnom Penh Group’ was also in the chain of command. The political bureau was also referred to as the Central Committee, Permanent Committee or Committee 870, composed of Pol Pot, Brother Nuon, Brother Ieng Sary, Brother Vorn, Brother Son Sen, and Brother Khieu Samphan. Two members of the Standing Committee were not members of the Permanent Committee, because they did not attend the weekly meetings in Phnom Penh.

The hierarchy of the committee was a complicated one, as offices and officials are referred to with different names. However, after a number of necessary clarification questions from the Civil Party Lawyer as well as the President Nil Nonn, it seemed that the structure was made clearer.

What was told to prisoners when they were interrogated?

After the break, it was now time for Mr. Lysak from the Prosecution to take on the witness. He had asked several infructuous questions relating to former Lon Nol soldiers coming back from the United States[9], but soon went back to interrogation methods at S-21. Duch said once again that the methods were consistent with the idea that interrogators should not reveal through their questions what information they wanted to obtain[10].

In a letter written from Pon to Duch shown by Mr. Lysak, the witness pointed out that the interrogation methods indicated what he had instructed Pon in order to interrogate Bong Ya, an “important individual within the party” according to Duch.[11] Mr. Lysak sought to know if previous confessions were quoted to interrogated prisoners in order to pressure them. In the same document, he found sentences revealing this both from Pon and from the witness’ handwriting, which the witness did not deny.

Furthermore, there was evidence that a method of torture was to use the names of the people who had incriminated the prisoners, which Duch confirmed as well[12].

When Mr. Lysak moved on to his next document and quoted an extract of a confession[13], Co-Lawyer for the Defense of Khieu Samphan Anta Guissé rose to her feet and objected to the use of such quotes, as there was a presumption against statements obtained under torture. Deputy Co-Prosecutor Dale Lysak explained slowly and clearly that even if these statements were barred according to the Torture Convention (Article 15: “Each State Party shall ensure that any statement which is established to have been made as a result of torture shall not be invoked as evidence in any proceedings, except against a person accused of torture as evidence that the statement was made.”), the quote used here was not a confession, as the prisoner said he was innocent. Ms. Guissé maintained her objection and after the Judges discussed it for several minutes, they sustained the objection and told Mr. Lysak to move on to another document.

Mr. Lysak intended to use this quote to show the process of torture and what was shown to prisoners during interrogations, but the Judges deemed that there could not be exceptions based on the content of the quote. The presumption stood strong.

Health at S-21

Mr. Lysak showed, much like during parts of his questioning of the witness last week, that it was common practice to execute the weakest prisoners. On the list he showed, the majority of prisoners had infectious diseases, were seriously incapacitated, pregnant[14] or over 70 years old[15]. When Mr. Lysak asked the reason behind this practice, Duch answered once again with a sinisterly famous line from the time of the regime:

“To keep is no gain, to remove is no loss”.

The last two lists were compiled lists, and Duch reminded the Court, waving an accusatory finger, that the numbers on the master list of S-21 prisoners had changed a few times between the time of his trial (in 2009) and now. The President interjected and said that it was appropriate for the witness to have more time to review the lists so that he could provide good answers.

Duch had been more defensive today than during the other days. After several contestations and lengthy explanations, Judge Claudia Lenz intervened:

“Mr. Witness, your trial was a separate trial, this is a separate trial. So whatever the Prosecutor, or anybody else have said in the first case […] is of very limited importance in this case. Second, yes there is additional evidence that you are not familiar [with] yet, […and] we have to deal with it. So it doesn’t really help that you tell us […] you don’t like [a document] because it wasn’t presented to you in your own case. I invite you to comment on the document, as far as you can […]. Is this clear?”

Further discussions and objections revealed that Duch had in his possession the OCP S-21 Prisoners Lists that he wanted to look at this moment – however, the document given by the Prosecution was a compiled OCIJ list in order to ask targeted questions. It seemed like Duch had assisted the compilation of this new OCIJ list. The President called for a break, after the confusion engendered by the debate over the last document.

Vietnamese soldiers at S-21

The witness was sitting straight in his chair. He had spent the last session bent over the documents, studying them carefully as always. For this line of questioning, Senior Assistant Prosecutor Mr. Lysak continued presenting many documents to the witness, each one precisely supporting his point.

“Mr. Witness, who instructed you to make audio recordings of confessions of Vietnamese soldiers that could be broadcast on the radio?”

“Brother Nuon.”

During his trial, Duch had explained that he “ordered the interrogators to do what it took to achieve the objective of the upper echelon. That is, Vietnam invaded Cambodia to join the Indochinese federation”, in order to get material for radio broadcasts. He further said that the content of these confessions were sent to Nuon Chea, and that he was the one who “provided some changes to the confessions”[16].

More than the radio, propaganda movies starring Vietnamese soldiers were also made. Duch described them without any question from Mr. Lysak. The cameraman was Theng, Pol Pot’s nephew. Photographs of the soldiers were also taken, before “they were smashed”[17].

Duch recounted that the party had troops searching the country for Vietnamese[18] and that himself and Pon were well aware of it. He added that this practice ended in 1974 and that they had let the remaining Vietnamese go home, though this was in contradiction with a previous interview the witness had previously given[19].

Chain of command and looking at confessions

Mr. Lysak sought to determine if the witness was aware of the content of the confessions, which would imply that his knowledge would go beyond simple administration and delegated tasks. Duch said he would usually review the content of the confessions, highlight the interesting parts and make short annotations. The interrogators were responsible for the content. Mentioning the case of Long Li, alias Yun, Duch detailed the chain of command as including Pol Pot, who sent the annotations to Son Sen. If there was a modification to be made, the witness said he had to take it up to his superiors, including Hor.

Khieu Samphan

The Prosecution asked Duch the role Khieu Samphan had between April 1975 and January 1979, to which he answered that contrary to the public announcement over the radio was that he was the State President of the Democratic Kampuchea, he was the chief, the chairman of various committees surrounding the center[20]. He was in charge of the Ministry of Commerce. Sivasy, alias Dun had the nominal position, but Khieu Samphan had the authority as well. Dun was in charge of communication and logistics.

After the witness gave further details entangled in references to other members of the structure, Mr. Lysak simply asked if Duch knew about the organization when he was the head of S-21 and if yes, how he knew. The witness specified that he and Son Sen’s in-law had friendly relationship and he used to visit him at the Ministry, which is why he learnt about it.

“What was [Chim Sam Hok, alias] Pang’s position in the center office? Can you explain the difference with the positions that Khieu Samphan and Dun had?”

“Initially, though Pang was the chairman of an office in the center office. Brother Nuon said that Pang could replace me on some tasks, […] Pang was the chairman of the office of the center. However, I saw later a document saying Pon the chairman of S-71. He was the assistant to the center committee.”

“Did Pang ever talk to you about Khieu Samphan?”

“Pang said bad things about Brother Khieu.”

The end of today’s questioning promises interesting developments for tomorrow’s hearing, as the hierarchy now seems clearer and it seems like Duch will be able to further inform the Court about the role Khieu Samphan had within the party. The testimony will resume tomorrow, June 14th at 9am.

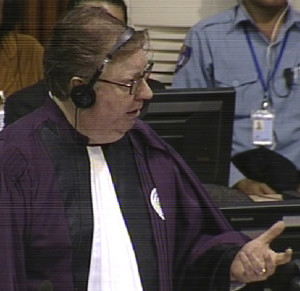

Featured image: Khieu Samphan (ECCC: Flickr)

[1] 09/06/2016. 15h25: “I am only aware of one case, a young man who assaulted my former teacher”.

[2] E3/10277, at 01017149 (KH).

[3] E3/7463, 21/07/2009, 15h53. Prak Khan: “Towards the end of the [S-21] period, when there weren’t women interrogators anymore, men were back at interrogating women. Windows and doors were open so that nothing there would be no licentious behavior.”

[4] 26/04/2016, Lach Mean, 10h02. “Were there some female interrogators? No female interrogators, just Pon’s wife who worked there. [ . . . ] Hun’s and Pon’s wives were the only ones to have access to the prison, but I don’t know if they came to interrogate.”

[5] E3/765, at 00376493-94 (KH), 0054 (FR). n10 of October 1978, principle n6: “Do not behave in any way that violates females. Never violate sexual morality in no case. Indeed, this issue tarnishes our honor and our influence as revolutionaries. This violates the noble and clean tradition of our population. Therefor on the one hand this damages our people and on the other hand, what is important is that if we violate sexual morality, which represents in fact the true nature, the true corrupted and stinking nature of enemies of all kinds, who would then have the means to manipulate and seduce us. We would be facing a very strong danger. [ …]”.

[6] E1/417.1, 18/04/2016 at 10h37”43.

[7] June 8, 2016.

[8] E3/12, 30/03/1976.

[9] E3/2017, at 00021137 (KH), 00183670-72 (EN); E3/3187, at 00008785-86 (KH), 00874237-41 (EN); E3/1757, at page 175, 00397090 (EN).

[10] E3/8681, at 00007470-71 (KH), 00225295 (EN), 00278759-760 (FR).

[11] E3/8374.

[12] E3/1705, 22/07/1977, at 00014091-96 (KH), 00183285-290 (EN), 00373117-120 (FR).

[13] E3/1891, at 0096819 (KH), 00017901-03 (EN). Ku Tuyn: “I am supposed to report about my plans for a coup d’état against the party, which I respect as much as I respect my own life. No intent of a coup d’état, preposterous as it has never crossed my mind”.

[14] E3/1041, report from Huy 24/03/1977. OCIJ list: n3259, 3306, 3289, 3272, 4422, 3248, 3270, 2119, 3292.

[15] E3/10506, at 01019379 (KH). E3/8657, at 00230070-71 (KH).

[16] E3/525, 2009.

[17] E3/5756.

[18] E3/834, at 00077476 (KH), 00184498 (EN).

[19] E3/1580, OCIJ interview 00177580, 00177587, 00177594-595 (FR). “after April 17, 1975 most of the Vietnamese who remained were eliminated; there were very few, but I remember the Vietnamese names on S-21 lists; civilians and military alike were sent to execution”.

[20] E3/347, at 00160890 (KH), 00184998 (EN), 00160922 (FR).

[…] [8] Witness Unravels Chain of Command under Khmer Rouge Regime, The Cambodia Tribunal Monitor, June 13, … […]