Son of East Zone Resistance Cadre Details ‘Internal Purges’

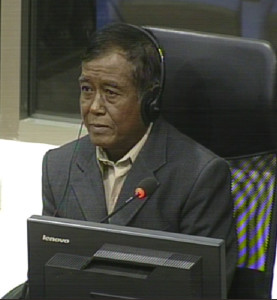

In front of a public gallery filled with pupils and Buddhist monks, Meas Sourn came to testify after Civil Party Chhon Samorn was done answering questions from the parties. The Chamber heard these two testimonies in the context of Case 002/02 against Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan. Like yesterday, the focus was on “internal purges” of Khmer Rouge Cadres from the East Zone but this time, witness Meas Sourn testified in relation to his knowledge as the son of East Zone District Chief Meas Seng Hong.

Civil Party Chhun Samorn ends his testimony

Before turning to Mr. Chhun Samorn, President of the Chamber Nonn Nil announced the Court’s decision concerning the request issued by the Defense of Khieu Samphan. When she summarized the request earlier this week, Co-Defense Counsel Anta Guissé asked for clarification as to what extent the knowledge of a witness made him sufficiently relevant to the “internal purges” segment. The President stated that the proposed testimony of Meas Sourn (2-TCW-917) fell within the scope of “internal purges” as laid out in the Closing Order issued by the Court. The witness possessed relevant information on the occurrences of purges in the East Zone.

Co-Counsel for the Defense of Nuon Chea Ms. Anta Guissé then continued her questioning of Civil Party Ms. Chhun Samorn. The witness started by explaining that he was posted at the front lines of the Vietnam border from 1975 to 1978, when he fled to Vietnam. There was an exchange program between Vietnamese and Cambodian soldiers, which the witness heard started after April 17, 1975. He did not know more details about it.

As a soldier, Chhun Samorn made oral reports, and he further confirmed that he had a radio his team could use to call the artillery to fire on a certain location after he gave a report. After the few questions stated above, Counsel Guissé then concluded her cross-examination.

After over a day of testimony, Mr. Chhun Samorn issued his victim’s impact statement concerning the crimes alleged against the two accused, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, during the Khmer Rouge regime. His emotional statement showed the extent of his suffering:

“I joined the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea in May, 1975. I had complete confidence in the upper Angkar to lead the country. I sacrificed myself for my nation, my country and for Cambodian people. I respected the plans of the party, and I implemented and adhered to all disciplines. I myself was engaged in fighting against the enemy. Sometimes, I went without food for two or three days. Sometimes, there was no water to drink. The situation was so miserable. However, as a result, myself and many East Zone soldiers were accused by Angkar of betraying the Party. We were arrested and sent for execution. I was in great shock at the time and I could not believe the act of the Regime. I was arrested, and I stood up and I made my protest that I was simply a combatant, I did not know about any betrayal. If that was the case, then only commanders were involved and I wanted the Party to find me justice. One of those soldiers beat me with the butt of a gun and accused us of betraying the Party, of having Yuon heads on Khmer bodies.

Then the commander ordered them to strip us of our clothes, and we only had shorts on our body. My right arm was beaten, it became paralyzed and remained paralyzed until the present time. When it became dark, they used a string […] to walk us on the execution site. [There], we were ordered to sit down. There were seven or eight of them who were armed with AK rifles and they pointed the guns behind our back. Then, they untied the four people at the front and took them to be executed. We could hear […]. Those who were not yet beaten screamed and then were beaten to death. We were all in great shock. I attempted to flee and while we were fleeing, they fired at us and those whose hands were still tied up were killed. Three of us could escape and they chased after us, firing at us from behind, and one of us was injured. We jumped into the water creek and they were standing at bank and fired into the water at us. I tried to swim to escape and I survived as a result. These were vicious acts inflicted to me. […]

Another misery was the loss of my relatives, including my elder brother-in-law who was a “new person” and was called by Angkar to transport feces to the cooperative in 1976. He was arrested and disappeared since. As a result, his wife became a widow with three children, and now I bear the burden of taking care of them. My other brother, who had complete trust in Angkar and the Revolution, joined the Army in 1970 […] and worked at the staff office of the East Zone. In 1977, Angkar called him to a training session and he disappeared since.

During the period of Democratic Kampuchea, my property was confiscated and put for common use in the cooperative. As a result, I lost all those properties.

I would appeal to the Chamber to find justice for my family. Thank you.”

Mr. Chhun Samorn then formulated his questions to the accused, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan:

“I am not a well-educated person, but I want to ask why [the Regime] divided people into two categories, the base people and the new people? Secondly, why were many East Zone soldiers arrested without justice?”

The accused made no change as to their previous wish to exercise their right to remain silent. Civil Party Mr. Chhun Samorn’s questions remained unanswered as he stood up and left the courtroom.

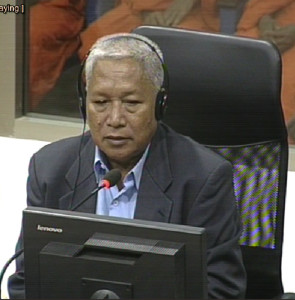

Introduction of new witness Meas Sourn

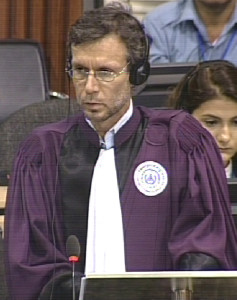

International Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde took the floor before the second witness came in the courtroom and asked for more time, arguing he was the only witness who was going to testify on purges in the East Zone. After the examination of former Head of S-21 Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch, last week, the pace of questioning was distinctly faster. The interrogation strategies were somewhat clearer now, as the same elements were tackled by different parties on the same day.

Witness Meas Sourn (2-TCW-917) was born on June 11, 1952 in Phnao village, Memot District, Tboung Khmum Province. Currently, he is a member of the Kandal Provincial Committee. Mr. de Wilde proceeded to ask the witness about how he got knowledge relevant to “internal purges” in the East Zone of Democratic Kampuchea. The witness said he escaped the Regime in 1968. He paused, and explained that the soldiers made him and other villagers run into the forest out of fear, they were not aware they were in the Revolution. During the Regime, Mr. Sourn was a member of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) after starting by working as a messenger and driver for his father, Meas Seng Hong – District Governor of Sector 21, in the East Zone.

“Mr. Witness, when you went underground, did you follow your father? Did you work with him?”

“No.”

Asked about his father, the witness recalled that he had been a District Chief of Sloeng after 1975. He had also heard that his father was part of the Resistance, with Issarak fighters (armed leftist group with strong ties to Vietnam, powerful before the independence of Cambodia in 1953). Mr. Sourn did not know, however, if his father had developed any ties with Pol Pot and Nuon Chea while he was District Chief of Sector 21, in the East Zone. Mr. de Wilde made reference to the book of an academic, in which the opposed was stated. In his book “How Pol Pot Came to Power”, Ben Kiernan describes how Nuon Chea and Pol Pot had close ties with the Deputy Secretary Seng Hong, alias Chan, father of the witness. According to the book, the two leaders regularly stayed in Chan’s house and gave him political instructions. One cadre even stated that they trusted Chan more then Sao Phim, high-ranked Military Commander under the Khmer Rouge.[1]

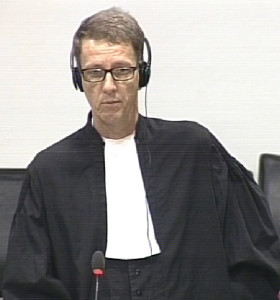

For the “sake of completeness”, Co-Counsel for the Defense of Nuon Chea Victor Koppe pointed out that another academic – Steve Heder – held the opposing view and described Chan’s position as being close to Sao Phim’s position, and not above[2]. Insisting in vain, Mr. de Wilde wanted the witness to react to the alleged strong links between Pol Pot, Nuon Chea and Mr. Sourn’s father. The only information the Mr. Sourn could recall was that his father became Deputy Chief of the East Zone around 1974. Mr. Sourn denied he had been a member of the Revolutionary Youth’s League.

Father and son relations with the Party

Mr. Sourn described how he worked in a factory specialized in metallic spare parts. He was the Deputy Chief of the factory and had started his training in 1975, when he was already a member of the CPK. The witness went to CPK meetings held in the evening. Mr. de Wilde asked him if he had any relation with Koy Thuon, former Khmer Rouge high-ranking leader, as well as other leaders, but Mr. Sourn denied he did. As a messenger, he “only brought letters concerning the requirements of the East Zone to the Commerce Office”.

“I never attended a study session convened by Sao Phim.”

“I never met [Sao Phim].”

Mr. de Wilde then inquired about the chain of command the witness was aware of, especially in relation to Sao Phim. However, Mr. Sourn denied he ever met Sao Phim or attended a study session chaired by him. Later in his testimony, the witness would describe how he had in fact met Sao Phim in another context.

Concerning the succession to his father’s position as Secretary of the East Zone, the witness was only aware that Ta Phum preceded him, and that Ta Chean succeeded him as Head of Sector 21 and was then moved to Sector 22. The latter figured on a list of people interrogated at S-21[3]. Secretaries of regions 20, 23 and 24, all in the East Zone, were also found on the S-21 list.[4] [5] Witness Meas Sourn referred to the “purging of all East Zone cadres”, including Sao Phim, which according to him occurred in 1978.

Mr. Vincent de Wilde succeeded in showing that many cadres from the East Zone, most of whose identities were confirmed by the witness, were on an S-21 list from 1978. According to Mr. Sourn, these cadres were accused of betraying the Party and colluding with the Yuon (the Vietnamese).

“When the chief was arrested, his subordinates were also gone. […] ‘Study sessions’ was the excuse they used. They never said they were subject to arrest, they only said ‘Comrades, you have to attend a study session’.”

Though the witness was able to detail such a practice, he was not aware if the Standing Committee issued the decisions to arrest the cadres. Senior Assistant Prosecutor Mr. de Wilde was relying on a statement made by former Head of S-21 Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch, who had told about a one-time occurrence of such an arrest order being issued. [6] He pressed the witness, as Sao Phim was also part of the Standing Committee at the time, but Mr. Sourn was not aware of such order being issued.

Mr. Meas Sourn was also not aware or of the involvement of his father in meetings and events in the higher ranks, but Mr. de Wilde quoted a report of the Standing Committee on negotiations with the Vietnamese, which detailed a meeting in which were present a number of higher ranked officials, including Comrade Von, Khieu, and Chan. Comrade Chan, Meas Seng Hong, even took the floor twice.[7]

Before the President called for a break, Co-Defense Counsel Victor Koppe took the floor to react to the Prosecution’s request for additional time. Mr. Koppe observed that the reason why Meas Sourn was the only witness to testify on “internal purges” in the East Zone was because the Court still had not ruled on the Defense’s list of witnesses. The Chamber still granted Mr. de Wilde an additional 40 minutes.

East Zone cadres: policy of purging from the upper echelon?

Witness Maes Sourn, son of former District Chief in the East Zone, continued to testify on purges of East Zone cadres. Mr. de Wilde listed names of District Chiefs in the East Zone who were taken to S-21, but the witness could not recall names. Among them were Mai Po, former Head of Sector 21 and Head of telecommunication at the Rubber plantation in the East zone; Pech Phorn, alias Po[8]; Chhom Sarat, Secretary of Schlong District and Pim from Chinlong District. However, he recalled hearing that groups of traitors were arrested in the East, in 1977. [9]

The witness added that before May, 1978, two Heads of Districts and some messengers had disappeared, which made the others, including him, scared[10]. He also remembered that one Vietnamese from his section in the factory was arrested, but did not know the chain of command for the arrests.

Mr. de Wilde attempted to find out it Meas Seng Hong had led a revolutionary movement the witness was aware of, but in Mr. Meas Sourn’s opinion, his father was loyal to the Party. After referencing one more document which mentioned that Nhim, a Khmer Rouge military, required “additional opinion by Angkar”, or Office 870, in the selection of Cadres, Mr. de Wilde asked if the witness knew about a practice to ask for the agreement of the Party, including here in the context of “purges” in the East Zone.[11]

The witness recalled that on May 25, 1978, there were major purges in Democratic Kampuchea. He told the Court that he had witnessed measures in relation with countering the advancement of the Vietnamese Army: trenches were dug, and people were arrested along National Road 7 and movements were restricted. “Even pregnant women were not allowed to leave”, he added.

Mr. de Wilde asked Mr. Meas Sourn about a letter his Chief had received from Sao Phim that day, on May 25, 1978. The letter stated there was a coup d’état led by Son Sen’s armed forces and that the Unit should be ready to defend itself. In a second letter, Sao Phim said that he was going to make his way to Phnom Penh to see Pol Pot and Nuon Chea. However, the witness then described how Sao Phim was accused of being a traitor to the Party:

“Helicopters and airplanes dropped leaflets in the east Zone saying that Sao Phim was a traitor selling his head to the Vietnamese.”

Though he previously stated that when a cadre was incriminated, his subordinates were too, Meas Sourn did not know why his father, who worked for aSo Phim, was not taken away and executed. Mr. de Wilde pressed the witness for more details about his last encounter with his father, to which Mr. Meas replied:

“In 1978, when he left on a ferry for Phnom Penh. […] It was three or four months before the Vietnamese entered Phnom Penh. [Since that day], I never saw him or hear from him again, as well as my sibling who had gone with him.”

Meas Seng Hong executed

Mr. de Wilde confronted the witness with two testimonies – Ieng Sary, third-in-command after Nuon Chea and Pol Pot, in an interview to Steve Heder and Nuon Saret, quoting Khieu Samphan – asserting that his father, Meas Seng Hong, had been arrested and executed towards late 1978 or early 1979. There was evidence of him being taken to Tuol Sleng.[12] [13] However, witness Meas Sourn refused to pronounce his father dead:

“If he died, I did not know where he died, and if he is alive, where he is living.”

Mr. de Wilde then wanted to know if the witness was aware of details about the treatment of the Cham, an ethnic minority, from 1975 onwards. The witness stated he did not know about the time frame, but that “Islam people”, who lived in Krouch Chhmar District, staged a rebellion. Before that, there had been purges and discrimination against the Cham[14]. According to the witness, they were mistreated by the local authorities and “they could no longer stand it”. Though Mr. de Wilde attempted to establish that the targeting of the Cham was a policy implemented by the Khmer Rouge, witness Meas Sourn said he never saw a document to that effect.

Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Lor Chunthy asked a few of questions to the witness, including regarding Sao Phim. In contradiction with what he had said earlier, Mr. Meas Sourn now said he had met Sao Phim at his house, in Soeung Village, Tboung Khmum District. He was assigned to go and seek advice about preventing “internal purges”, but he had not obtained a clear answer.

Counsel Lor Chunthy asked the witness about his father, and he repeated:

“Mr. Witness, can you tell the Chamber whether you believe he is still alive?”

“As I said, I am not sure. If I knew he was alive, I would try to find him.”

For the last part of the day, Defense Co-Lawyer for the Defense of Nuon Chea Victor Koppe was granted the floor.

First, Mr. Koppe asked the witness to react to one of his previous statements, in which he had said his father had told him to pretend to be a farmer in Kampong Trabek and that he should not “speak about the previous things in Sector 21”.[15] It seemed like the witness was revealing that the Party’s suspicions were closing onto Meas Seng Hong: added to his advice to keep silent, the witness recalled that Son Sen replaced his father’s bodyguards with some of his own personnel.

“Mr. Witness, what was your father trying to conceal?”

“If we happened to know much, it was difficult to live through the Regime.”

Rebellion against the Regime

The witness was unaware of details about a staged rebellion against Angkar, both regarding the rebellious forces and the forces which crushed it. He only confirmed that his father, Meas Seng Hong, was second-in-command (Deputy Chief) of Sao Phim from late 1974.

Defense Counsel Koppe then showed a video extract showing the visit of Pol Pot and possibly Vorn Vet, as well as Sao Phim and Son Sen, at a rubber plantation in early 1978.[16] The witness was only able to recognize Pol Pot. Moving on, Mr. Koppe asked the witness if he knew that Chan Chakrei, together with his father, were selected to be revolutionary role models in 1974: “I did not”, the witness answered.

Featured image: Witness Meas Sourn (ECCC: Flickr)

[1] E3/1815, at 00487327 (EN), 00104787 (KH).

[2] E3/3995, at 00773726 (EN), 00802812 (KH), 00844574-5 (FR).

[3] E3/2229, at page 3 (KH), page 4 (EN) (FR).

[4] E3/1949 and E3/2494, E3/2990.

[5] E3/5531.

[6] E3/345 and E3/5799.

[7] E3/2221.

[8] E3/1563, at 00175121 (KH), 00962767 (EN), 00827894 (FR).

E3/2285, at 00009299 (KH), 00873624 (EN).

[9] E3/2096, at 00006753 (KH), 00182908 (EN).

[10] E3/5531.

[11] E3/1205.

[12] E3/89, at 00417638239 (EN), 00332719220 (FR).

[13] E3/4650, 00436892 (EN), 00392125226 (KH), 00463029230 (FR).

[14] E3/5331.

[15] E3/5531, Question and Answer 66.

[16] E3/3015R.