“I Consider Myself as Somewhat the Voice of Ordinary Cambodians” – Henri Locard Testifies

Today, July 28, 2016, witness 2-TCW-1005 concluded his testimony by answering Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé’s questions about communication methods and practices between senior cadres.

From the second session onwards, expert witness Henri Locard provided his insights to the court. He was questioned about the books he had written and the process for writing them, as well as his knowledge about security centers. He was reminded several times to give concise answers to the questions.

Kirivong

The Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn announced that 2-TCW-1005 would conclude his testimony today, after which expert 2-TCE-90 would be heard. All parties were present.

The floor was granted to the Khieu Samphan Defense Team. Anta Guissé asked who his direct superior was in Kirivong. The witness answered that he was with Phorn in the regiment in Sla Village. Phorn was transferred and he was assigned elsewhere. The witness supervised around ten to twenty people. They were all messengers. He became head of the platoon later at an age of 13 to 17 years. They delivered messages about meetings. The division was not yet formed when he was at the platoon. There were other companies beneath them. The division was formed in 1977. He delivered messages between the platoon and the battalion in Kirivong. He was stationed in the south of Kirivong. He was not allowed to operate the radio or telegraph yet when he was in Kirivong. He only started using a radio when he arrived in Kratie. To do so, he was trained over a period of three months, but the actual training lasted 1.5 months, after which he returned. He was also trained how to decode messages with a telegraph. At this point, he did not see the magazine yet. The trainer read from a hardcopy of the Revolutionary Flag during the study sessions, but he never personally saw this hardcopy. “We were instructed that we had to be honest”.

Ta Mok and Other Cadres

Turning to her next line of questions, Ms. Guissé wanted to know how he concluded that Ta Mok “was in charge of everyone” and that people “loved him”. He replied that it was his personal conclusion. At the time before he left Kirivong, he “observed that those soldiers or the army medics loved him. For example, when he went to visit the hospital, he would instruct the medics to carefully treat the wounded soldiers […]. And he was a man of loud words, but he could resolve the situation”.

Ms. Guissé read an excerpt of his interview, in which he had said that “Ta Mok was above all others in the Southwest Zone”.[1] The witness replied that he “could be in charge effectively of the whole zone […]. All [four] sectors were under his supervision”. His deputies did not dare to dissent. He did not remember the full name of Ta Mok’s son-in-law. Khom, who was the wife of Meas Muth, had passed away. The son-in-law included therefore Meas Muth, another teacher who got married, and Hor (passed away). Boras and Yeay Hing were at the division level, but had passed away. He did not know the youngest child – Chrut – personally.

Ms. Guissé asked about the cadre Ta Tom that he was questioned about by the investigating judges. In his interview he mentioned Ta Naim, Ta Tith and another cadre.[2] The witness remembered that Ta Tom was his cousin, since he was the cousin of his ex-wife. His mother went to Kirivong Hospital together with Ta Tom’s wife. Ta Tom supervised a platoon. When he went to visit the house, he had been removed and the military commanders who were under him were also sent away. “And that was the end of the matter with his subordinates”. Ta Thit told him about his uncle that the soldiers under him were not “well-disciplined”. “Upon hearing this, I quickly went to Kratie and I did not spend time visiting my mother”.

Ms. Guissé probed further on the issue and asked why he had concluded that Ta Tom “had issues” because he had soldiers under his order.

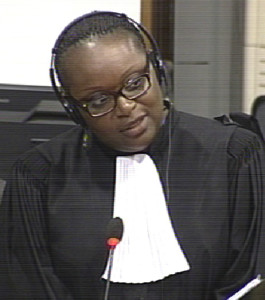

International Khieu Samphan Defense Co-Counsel Anta Guissé

Ta Tom was not his uncle, he said now, but his mother was Ta Tom’s cousin. Ms. Guissé then wanted to know whether Ta Tom had “problems concerning his behavior” when he was drinking wine, which was prohibited at the time.[3] The witness answered that “he drank wine and he had issues within the army. He in fact drank wine from the jar that he used to keep wine. When I was walking from Tom’s house […] I saw the wine jar.” He was asked where Ta Tom was, and he said that he had visited his house. However, Ta Tom was not present there. He did not know whether Ta Tom had consumed alcohol.

Conflict with Vietnam

Ms. Guissé then asked about “incidents” in which soldiers had turned their own weapons against each other to get away from the front. She wanted to know whether he witnessed this himself. The witnessed recounted that 200 soldiers were killed from a shelling. At the time, the soldiers were eating their meals. The shell missed their target and as a result, 200 of their own soldiers were killed. One hundred soldiers were using the artilleries, but they could not use the Vietnamese targets. They only had small artillery, whereas the Vietnamese were better equipped.

The witness himself was in charge of the messengers, the drivers, telegram operator and clothes-making workers. He had the authority to communicate with the commanders and send reports to them.

“I could solve the problems in relation to ammunition, food, uniforms, etc. And I was entitled to solve these problems for all the brothers at the battlefield. I did not hold a high-ranking position. And my rank could not be compared to the regimental level, I was below that. Whenever there were meetings of regiments, I was not invited to join the meetings”.

Reports and Communication

Concerning three individuals, he would make daily reports to the General Staff and one of them had the authority to receive his reports. It depended on these three individuals whether they would answer. He would make reports to them concerning how much ammunition he needed. “If information was leaked, danger would be bestowed on the soldiers”. If messages were not correctly encoded and de-coded, this would signify danger.

The telegraph was “a little bit away” from these three individuals. “It was so complicated concerning message formulation. It is easier in this current period of time. We can do it faster, because of modern technology”. There were sets of telegraphs there.

Ms. Guissé asked about a letter that he had said he received from Office M-870.[4] Thy and Kung were in charge of messages for Muth. The latter was at another location together with the messenger at Tuol Sambol. Thy was originally “from the airfield”. Meas Muth and Thy and Kung had not worked together in the past.

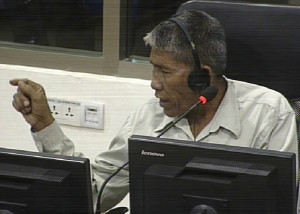

Witness 2-TCW-1005

Thy and Kung were the personal messengers of Muth. They came from the airfield 502. Thy and Kung were driving north after bringing the message. This was a written or typed message. Usually the message was encoded. Messages were usually delivered through telegrams. The message was originally encoded. There was only one handwritten letter during the time that he stayed there. “It was very difficult to deliver any hardcopy mail from Phnom Penh.” It was difficult to find an airplane to transport the wounded soldiers already, so messages were usually sent through telegrams.

Ms. Guissé wanted to know whether he saw the code M-870 on the letter or whether there were other annotations that led him to believe that it came from the headquarters. He replied that when it came from the airport, they knew it was from M-870. However, it went through the unit at the airport. The message was not a handwritten letter from the General Staff to them, but went through the airport staff.[5]

Ms. Guissé asked how he knew that M-870 was “Pol Pot’s State Office.[6] He knew that it was a State Office, because it belonged to the leadership. He did not know whether it belonged to a specific leader. Office 870 did not have any direct communication with them, but send the communication through 502, since this was based in the airport. On a monthly basis, they transmitted the messaged to 502, who would transfer it further.

Ms. Guissé asked about a note on one of the messages. The witness could not recall the head of the message, but could recall the content: the Vietnamese were attacking. Upon seeing this, they knew that they had to prepare their forces. Ms. Guissé wanted to know whether he had access to the communication between Meas Muth and Son Sen. He answered that it was “based on [his] analysis”, but that he did not know the details. When one of them was absent, they had to communicate through messages to solve military situations. He personally did not see the communication between them.

Letter to Summon Rom to Phnom Penh

Ms. Guissé then turned back to the letter that had been subject to discussion for the past two days already. She wanted to know where he could see the annotation on the letter. He answered that it was on the top right-hand side: M-870. The envelope addressed Rom. When he left, the letter was left on the desk. He did not pay attention whether there was any other code name on the letter.

Marriages

National Khieu Samphan Co-Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn

With this, Ms. Guissé gave the floor to National Co-Counsel Kong Sam Onn. He asked the witness to elaborate on marriages of soldiers: how many soldiers got married and how many times did he participate in this ceremony? The witness could not recall how many couples got married. Sometimes medics got married and sometimes workers of the garment factory. He could not recall any specific person. He lost contact with all of them since returning from the northern part of Cambodia in 1982. Mr. Sam Onn asked whether he partook in the decision-making process regarding couples getting married. He replied that he did not have the authority to do so, since this lay with the division headquarters. This also applied if two people “loved each other”. Sometimes they talked about the marriage with the couples, but sometimes “they were shy to talk about their new situation”. Moreover, “in practice we did not have time to chitchat with one another.” At this point, Mr. Sam Onn concluded his questioning.

The president thanked the witness and excused him. He then adjourned the hearing for a break.

The Testimony of Expert Henri Locard Begins

After the break, the testimony of expert witness Henri Locard began. He was born on 11 June 1939 in Lyon and speaks French and English, as well as a little bit of Khmer. He said he would answer in English to questions in English, French to questions asked in French, and in French to questions in Khmer in French. He is from Lyon, but currently resides in Phnom Penh. He retired from Lumière University in Lyon is now a volunteer at the Royal University Phnom Penh in the history department. He is Roman Catholic and took his oath in front of the judges now. The president informed the expert that he was not allowed to give any judicial opinion on genocide, since this was a matter to be decided by the Chamber. Mr. Locard agreed to this, but said that the tribunal seemed to have forgotten one minority: the Khloeng, which were of Pakistani origin. According to Mr. Locard, he had evidence that they were collected at the beginning of the regime and were all exterminated simply because of their ethnicity.

He received his education in Lyon and at the Sorbonne in Paris, as well as in England for three years. He started his career as an English teacher in 1965. As a student, he came to Cambodia in 1964 to examine a rubber plantation in Ratanakiri.

At a later stage, he had tried to understand why “so many people died” and started his research on Democratic Kampuchea in 1990. Ten years later, he pursued his PhD on the ideology of the Khmer Rouge and provincial prisons. He wrote his doctoral thesis mainly to understand why so many people – some of them friends of his – disappeared and died. After having spoken on the radio at a local Khmer radio station in Lyon, Cambodian refugee Moeung Sonn contacted him. Moeun Sonn had been imprisoned during the Democratic Kampuchea and wanted to write his story. Subsequently Mr. Locard recorded Moeung Sonn’s story over the course of a year.

“There was not a single region, province, district, where there was not a major prison during Democratic Kampuchea”.

They published Moeung Sonn’s memoirs. Since he collected extensive information about Democratic Kampuchea through these interviews as well as in the course of writing articles, he had sufficient knowledge to write his thesis.

At this point, Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé interjected and said that it seemed like the expert was reading from notes. Mr. Locard thanked her for asking this, and then held up the paper that only had the oath written on it that he had to repeat a few minutes earlier.

Publications

He published Prisoner d’Angkar and Pol Pot’s Little Red Book (published in both French and English – he pointed out that he would call it differently today, since the Khmer Rouge were not only led by one individual. Pourquoi les Khmer Rouges constituted a summary of his findings and a second edition with “many corrections” was to be published this month. Mr. Locard reaffirmed his belief that the Court was helpful:

“I do believe that this court is throwing new light on the Democratic Kampuchea regime”.

For another publication, he worked together with Cambodian expert Suong Sikoeun (who had also testified in court): “Suong Sikoeun is a very difficult person to work with.” He had also worked with Phy Phuon, a Jarai who had testified in front of the Chamber and had died a year ago. They had concluded their work before Phy Phuon passed away.

He pointed to Philip Short’s The History of a Nightmare (which Mr. Locard later praised as “by far the best book on the Khmer Rouges”), as Mr. Short had interviewed Khieu Samphan and Mr. Locard argued that a “very important source to understand the Khmer Rouge Regime” were the Khmer Rouges themselves.

Asked about expertise regarding genocide, he told the court that he had done some research on Crimes against Humanity and did not consider himself an expert on genocide. Apart from the Khloeung, he had not conducted specific research on genocide.

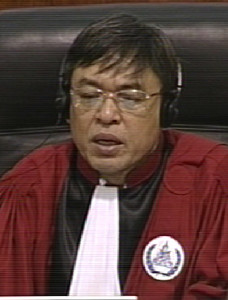

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

The president then sought more details regarding the book Pourquoi les Khmer Rouges and Mr. Locard explained that he started writing this book in around 2010. As for differences in the editions, he explained that he had eliminated a few paragraphs that he had been told were too controversial and put in new information that he had received through his interviews, the court and readings. He pointed out a few things he was not happy with – for example, the new cover did not show Pol Pot anymore, but only Nuon Chea, despite his wish to include both of them. He had reviewed the book in many passages: “I always hope to improve myself”

Prisons

The main subject area that he has expertise in were provincial prisons. He said that it was regrettable that the tribunal focused on S-21 and internal purges, as well as singled out victims such as Cham and Vietnamese, and did not focus on “ordinary Khmer people”. They included around one third of the people who were massacred or died under Democratic Kampuchea. Recounting his first research, he said that he tried working with the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam). DC-Cam had wanted to investigate the pits, which he claimed had already been researched. Mr. Locard said that it was much more important to research the areas that had not yet been discovered and focus on detention centers that had been discovered by David Hawk. His proposal was not accepted by DC-Cam however:

“First because I was a Frenchman, and DC-Cam and the director is not very fond of French people apparently and doesn’t know French, he was American educated, and two I came with my pockets empty, I came with no money .”

He had continued his research until the tribunal was established and he thought they would cover the rest. At this point, he had covered around 50 percent to two thirds of the country, he estimated. To his disappointment, the tribunal had not done enough field research on the principle or murder and extermination.

“It’s a little bit if you study the Nazi Regime, you concentrate on Auschwitz, Auschwitz, Auschwitz, nothing but Auschwitz. Yes, but what about the other concentration camps all over Europe? This is a little bit how I feel here.”

He was mostly interested in those victims who were “completely innocent” at the provincial prisons.

“I consider myself as somewhat the voice of ordinary Cambodians who suffered horrendous deaths”.

The president explained that the tribunal did not have the resources to investigate all these facts, and that its mandate only related to a limited period of time as well as specific crimes and facts.

Sources

As for the sources of his book, he had secondary and primary sources. Regarding secondary sources, he had read David Chandler’s books, as well as Philip Short, and others. The latter conducted more field work and interviewed more Khmer Rouge officials and intellectuals than the former. “His book is absolutely a mine of information”. As for primary sources, he pointed to the autobiographies of the victims of the Khmer Rouge, which accounted to a number between thirty and fifty, he estimated. Moreover, he had conducted his own interviews: “I do not know how many Cambodians I have interviewed […], but certainly hundreds of hundreds, if not thousands”. Another important source was the Foreign Broadcast Information which had speeches by cadres, propaganda and the like. He regretted that they had not recorded all of the songs of Democratic Kampuchea or slogans. The president took the opportunity to call for a break.

Further Information on Books

After the break, the president asked when he had started writing his book that was at on the case file. He replied that he started writing it in 1989/1990, after having come back from Cambodia in 1988. The book was concluded in 1993.[7] The same year, it was accepted by a publisher. He titled this experience as the “most dramatic” experience of Democratic Kampuchea. The book was the autobiography of Moeung Sonn. Locard organized his testimony in chapters. Moeung Sonn was imprisoned for 18 months during Democratic Kampuchea. “It was quite exceptional”. He pointed to the difference between the later Democratic Kampuchea and early Democratic Kampuchea. In 1975 and 1976, mostly people connected to the old regime, monks who refused to disrobe and people intellectuals were victims. In the second part of the regime, from 1977 or 1978, victims increasingly also included ordinary civilians. This could also be seen in Moeung Sonn’s history.

As a side remark, he said that he had read much information on China, Vietnam and Korea as part of the Cold War structures. He had observed the same tendency to remove people who were connected to the old elite in the other countries, although Democratic Kampuchea was more radical. They felt that the other three regimes had not been radical enough and therefore failed. He said that there was also a race with Vietnam. According to Mr. Locard, Khieu Samphan had said: “We had to rush because we came last in history”.

“You could survive in Democratic Kampuchea prison, either because you were completely uneducated, a real proletariat” and arrested by mistake, or “because they were some use to the prison.” Mr. Locard found particularly fascinating two aspects of Mr. Sonn’s biography:

- the life in a Democratic Kampuchea prison

- the history of the Khmer Rouge prison

He pointed to the “big purge of the East Region”, but also other purges throughout the country. He estimated that the death rate amongst the cadres might have been as high as 50 percent. Moreover, he argued that the people in the technocratic sector had the highest chance of survival, since they were useful, but were not political.

Interjecting, the president instructed him to give brief answers and then asked why he had chosen the title of his book. He explained that Prisonniers des Khmer Rouges had already been used by Sihanouk and that he therefore had to take Prisonniers d’Angkar. In English, he could use the title Prisoners of the Khmer Rouges. He wanted to show that the whole country was a prison, but that there were also these special centers that were “interrogation, torture, execution centers”.

The president inquired about the book Khmer Rouge: Prisons without Walls and wanted to know what the meaning was of this, to which Mr. Locard answered that it was a summary of his research about prisons. “It’s just a summary of what I found by my investigations of the Khmer Rouge provincial prison system”. He said that his investigations were incomplete, because he had “expected the tribunal to follow suit and to conclude my investigations”. Seemingly excitedly he said that he now had sufficient information to write another book that focused exclusively on prisons.

Next, the president asked about another book.[8] He recounted that thirty to forty year old people who he interviewed recounted the slogans. Having been a teacher, he was curious about these slogans: “So I collected them just for fun!” Throughout the 1990s, he realized that he had collected much more information and that their ideology could be understood to a certain extent through this. People remembered these slogans from oral tradition, since they were not written down.

Security Centers

The president said that the court focused on the security centers Kraing Ta Chhang, Phnom Kraol, S-21 and Au Kanseng and wanted to know whether the expert had covered the whole of Cambodia. Mr. Locard replied that he came across the four prisons selected by the tribunal, but that he did not cover every security center in Cambodia, since this would be beyond the scope of any researcher.

He had decided not to include the slogans found on the walls at S-21, because the slogans did not sound like Khmer Rouge slogans to him.

He had done extensive research on Kraing Ta Chan with a staff member of DC-Cam, who had given him the surviving archive of Kraing Ta Chan. “There were a few criminals who were arrested at Kraing Ta Chan […] Most of the victims were those who tried to escape to Vietnamese.” Another group of victims at this prison were Khmer Krom and other discriminated groups.

As for the other two prisons, he recounted that Au Kanseng was situated in Banlung. This village was a military barrack and the prison was located behind a hospital. As for the prison at Koh Nhek, he said that Sen Monorom was close to the Vietnamese border. Since they were afraid that people would escape to Vietnam, they moved it to Koh Nhek, which became the capital of Mondulkiri at the time.

He could identify different categories of prisons. For example, Siem Reap Prison was the “prison of the north”. Thus, there was a major prison for each zone. The srok (district) existed before the Khmer Rouge and after. Every district had at least one district prison. Kampong Thom and Kampong Cham had several district prisons. The closer to the center around Tonlé Sap and Tonlé Mekong, the more villages there were and the higher the population density. Thus, more prisons were needed. Each village had a police center, where people were first brought to. He estimated that there were at least 150 permanent prisons in the districts – adding other prisons that were established it was impossible to give an exact number. There were uncountable temporary prisons.

Prisons were very unequal in size and importance. For example, he categorized the detention center Au Kanseng and Phnom Kraol as belonging to the least important prisons: there were less than 100 prisoners, they were sometimes released and “tortures were very simple, mainly beating and using plastic bags”.

As for biographies, these were never written by prisoners themselves except at S-21. There were three interrogators. In normal district prisons, the shackles were iron, and wooden in some prisons only. One interrogator asked the questions, one took notes and the other beat the prisoners. When prisoners were freed, they would first sent to a re-education camp, before returning home. Executions were very frequent particularly in the Northeast.

The president inquired why most prisons did not use the code word santebal as was used for S-21. The expert said that he had not researched the code names.

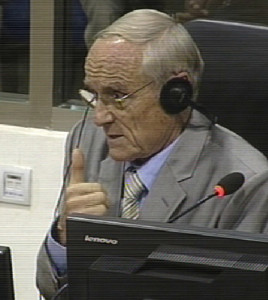

Expert Witness Henri Locard

The President asked whether he could tell the Chamber who had control over the system and what his sources were. Mr. Locard answered that he started from the grass root system and communes as well as ordinary prison to find out about the authority structure. “When an accused was being brought, there was never an accusation being made”, he said. The prisoner had to tell them why they had been arrested. Mr. Locard said that this must have been a directive, since the question was asked everywhere. The methods of torture were also very similar everywhere.

“This absolute conviction that Angkar is always right […], was a general pattern”.

This showed, in his view, that it was a highly centralized system. “The army was just the armed arm of the party” – the political commissar would order arrests. He argued that the structure of the country “was highly centralized. There was no horizontal communication, only vertical communication”. At this point, the president handed the floor to the Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne, who asked about the sources of the expert regarding the security centers. He asked whether S-21 and Kraing Ta Chan were the only centers where archives had survived, or whether there were more archives that had survived. He replied that Craig Etcheson had told him that two more had survived, but that apparently they had not been found. He explained the disappearance that some archives had simply been in a bad estate, whereas some were systematically destroyed. There was some revisionism about Democratic Kampuchea, where one wanted to make the public believe that there was only one main prison: S-21.

He criticized DC-Cam for not being open to the public, and in particular not to Frenchmen, to access their archives. They were directing people to their website. He had a friend who worked at DC-Cam, who made photocopies of the Kraing Ta Chan archive for him. As for S-21, they seemed to have only photocopies. Moreover, all archives were only incomplete.

Judge Lavergne asked whether he had used the help of a translator for the archives, or whether he had read them in Khmer himself. He replied that he had used the help of a translator, but that he also read them himself. He also went to the sight itself. He said that “Ta Mok was an exceptional character during the regime”. He found witnesses of the security centers, albeit fewer than the court, and interviewed them with regards to Kraing Ta Chan. Nowadays, it was poorly preserved. He was “not very professional” and did not take recordings before 2010. He had “many many notebooks”, however. He had made a condensed summary of his notes, but had more detailed notes at home. At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Different regions

After the last break of the day, Judge Lavergne retook his line of questioning. He asked whether he had taken notes or recordings of the interviews he conducted for the other two security centers that had not already been annexed to his work. Mr. Locard replied that he started researching in 1991, but that he only received the authorization to visit Ratanakiri in 1994. At this time he did not record his interviews. However, his notes covered all aspects of Democratic Kampuchea. He noticed a difference between Ratanakiri and Mondulkiri: people were much less enthusiastic in Mondulkiri and did not know Ieng Sary, Pol Pot and others, while people in Ratanakiri could tell him the beginning and development of the revolution.

Judge Lavergne pointed out that the Closing Order mentioned other security centers when it came to the treatment of the Cham, the Vietnamese, or worksites. For example, in relation to 1st January Dam, they had mentioned Wat Chambak, which the expert seemed to have studied. As for the 1st January Dam, he recounted that he had not studied his notes regarding all the provinces, since he had only two months to review his notes. As for Kampong Thom, he had visited practically all prisons in that region. He might have mentioned this pagoda, but would have to check his notes again. However, he had given all information he had and therefore did not have more information than the tribunal had.

For example, a worksite was kept secret and it seemed to be a taboo question on whether it was a site for the Chinese or of Democratic Kampuchea. In political terms, there seemed to be hesitations with regards to the involvement of the Chinese.

As for the treatment of the Cham, reference was made to Wat Au Trakuon in Kang Meas. Judge Lavergne inquired whether he had also studied this security center. Mr. Locard replied that the name rang a bell, but that he had not reviewed his notes on this part of this region or security center. However, he recalled that Duch had mentioned that there were Cham people at S-21. In Krouch Chhmar, there was a rebellion, which was “the most serious error they made”. When the Cham were arrested in that area, he believed that they were arrested to be executed. Judge Lavergne then asked about Wat Ksach and the killings of Vietnamese. Mr. Locard apologized and said that he could not recall this.

Asked about the slogans, he said that he did not note down the location where he noted them down every time, but that they could be found all over the country. They were disseminated throughout the country.

With this, Judge Lavergne concluded his line of questioning. The President asked to hear requests regarding the hearing tomorrow. Ms. Guissé requested to admit both versions of the 2013 and 2016 version to be able to compare them and ask the expert about the sources and changes of the two versions. The Co-Prosecution did not have any objection, nor did the Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers. The Nuon Chea Defense Team supported the request.

The President adjourned the hearing at twenty to four in the afternoon.

[1] E3/9814, at answer 30.

[2] E3/10622, at answer 123.

[3] E3/10622, at answer 25.

[4] E3/9813.

[5] E3/9813, at answer 29.

[6] 00980814 (FR).

[7] E3/2319.

[8] E3/2812.

Featured Image: Henri Locard (ECCC: Flickr).