Former Sector Soldier Talks About Conflict With Vietnam

Today, witness Chin Saroeun concluded his testimony. Under questioning of the defense team, he told the Chamber about Vietnamese incursions on Cambodian territory and subsequent arrests of cadres in Mondulkiri. The Co-Prosecution questioned him on ethnic minorities in Cambodia and in the border area of Vietnam and asked whether the Vietnamese who he had heard had secretly come to Cambodia might have been part of ethnic minorities and the FULRO movement. The witness could not shed much light on this. Lastly, he gave information on working conditions and arranged marriages.

Division 920

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn continued to be absent and was replaced by Ya Sokhan. The floor was granted to the Defense Team for Nuon Chea to commence the questioning of witness Chin Saroeun.

Co-Defense Counsel Victor Koppe asked whether he was interviewed by Documentation Center of Cambodia, which the witness confirmed. He could not recall the name of the interviewer. Mr. Koppe sought clarification about his birthday, since there seemed to be conflicting information about his birth year: 1954 or 1959.[1] The witness replied that the date mentioned on his identity card was his “official date of birth”. He reiterated that he was born in 1959.

Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

During the 1972 or 1973 period, he was a monk and then disrobed by Angkar in 1975. “Angkar’s commune transferred me to Mondulkiri”. He left Kratie Province when he was not yet a soldier and was in a mobile unit. He became a soldier in Mondulkiri in 1979. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he became a soldier rather in 1976 as part of newly created division 920. He replied that despite being in Division 920, he was still attached to his mobile unit and was not given weapons or tasks as a soldier. This was in 1976. “I was not given any weapon to carry when I was in Division 920.” He was only given weapons when the Vietnamese “encroached on Cambodian territory” in Mondulkiri.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he was a member of Regiment 93, which the witness confirmed. This was part of Division 920. The commander of Division 920 was Chhin, and Say was his deputy. He did not know about the previous establishment of Division 920. The headquarters of Division 920 were located in Sok San Commune near Au Chbar. He was not aware of a Division 920 base in Phnom Penh.

He did not know about the communications between Division 920 and other divisions. “I was a teenager from the civilian side and I was transferred to work in Mondulkiri.” Hence, he did not know about previous communications. Mr. Koppe asked whether the names Oeun and Soeung meant anything to him. “As I have just stated, I did not know them and I did not have any contact with them”.

He said that he himself was the head of a company in Regiment 3. Mr. Koppe read an excerpt of his DC-Cam statement, in which he had said that he was “only the chief of the company” because he was new.[2] Mr. Saroeun said that he could not recall everything he had said in the interview. He supervised 80 soldiers when being head of a company. This was the highest position he held in Division 920.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether it was correct that he became a sector soldier from early 1977 in Regiment 52.[3] Mr. Saroeun replied that he was part of Regiment 52 in Mondulkiri. He confirmed that there were Regiments 51 until 55. There were only two battalions: 501 and 502, which was noted as 51 and 52. In Battalion 502, he was in charge of logistics for the regiment. By that time, he was transferred to work along the border. Since the time that he was with Division 920, he was not given any weapon and was only a part of the mobile unit to engage in rice production.

Mr. Koppe inquired whether he had heard of a person called Lan. He heard that he was chief of Battalion 501. Kham Vieng was his unit chief. First, there was only one unit with Lan being the chief and Kham Vieng being his deputy. When the witness arrived, the unit was split and Kham Vieng became the head of Battalion 502.

Vietnamese on Cambodian Territory

Mr. Koppe asked who was in charge of independent sector 105 (Mondulkiri). He answered that Hom (also spelled Horm) was in charge. Kham Phoun was his deputy. Later, Sao Sarun was the chief. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he had heard of a person called Ya, also known as Ney Saran, which the witness denied. Horm was the chief of the sector before Mr. Saroeun arrived.

He did not remember who was in charge of Koh Nhek district. He then said that he thought it was Svay who was in charge of the district. He belonged to an ethnic minority. To his knowledge, Kham Phoun was Svay’s uncle.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he knew what happened in late 1976 or early 1977 in relation to Vietnamese troops. Mr. Saroeun answered that “there was not any serious matter taking place at the front yet”. However, “there was some problem at the district town”. The “situation” between Democratic Kampuchea and Vietnamese forces started in 1979, Mr. Saroeun said. He said that the “Vietnamese entered Cambodian territory, so our forces were armed”. [4] Mr. Koppe read an excerpt of his DC-Cam statement, in which he had said that “the Cambodian side did not do anything. The Vietnamese started first”, and that it started with the Kham Phoun movement. When Mr. Koppe continued to read excerpts, International Co-Prosecutor interjected and said that open questions should be asked first. The witness recounted that

Horm realized that Svay concealed the Vietnamese forces in the district, so plan to arrest Svay

Twelve Vietnamese soldiers “came in secretly”. Only when the “internal situation erupted”, they realized that something happened. Asked about more detail of the Vietnamese soldiers, “they were withdrawn from [Cambodian] territory after Svay’s arrest”.

The unit chief disseminated the information about Svay. As for the Vietnamese who were secretly brought into the territory, “They did not carry out any significant activity yet”. The Khmer Rouge quickly drew a plan to arrest the person who brought in the Vietnamese. Svay had a house in Kor Village.[5] He hid them in the nearby forest. When Mr. Koppe asked why Svay hid these Vietnamese soldiers and what his intentions were, Mr. Koumjian objected, arguing that it was a leading question. Mr. Koppe rephrased.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether Kham Phoun played any role in hiding the twelve Vietnamese soldiers. He answered that he only knew that Kham Phoun and Svay were relatives. “If any members [of a family] committed wrongdoings, there would be something wrong with other members”. The distance between their locations were “like between here and the USA today”. The witness was ordered to prepared forces to take measures to prevent Svay from escaping. They had two cars to arrest him. “But we did no arrest him, because Svay was already arrested at the district.” If the sector force had committed wrongdoings, the Division 920 “was instructed to perform the task”. When members of Division 920 “committed wrongdoings”, sector forces would arrest them. Asked whether Svay and Kham Phoun were considered as traitors, Mr. Saroeun answered that he was not aware of “internal issues”. He only knew whatever information was given to them by his commander. “There were problems between Horm and Kham Phoun”, but he did not know what exactly. He heard that the two sector chiefs died and that Kham Phoun killed Horm, after which he allegedly committed suicide. “That’s all I heard”.

Mr. Koppe read an excerpt of his statement, in which he had said that Kham Phoun led the Vietnamese into the country with Svay and recounted an attempt of a rebellious movement.[6] Mr. Koppe asked whether anything that he had read “was not correct”. Mr. Saroeun said that he stood by his earlier statement. “That interview took place a long time ago and I cannot remember every detail”. Mr. Koppe then wanted to know what he meant with Svay being “affiliated with a yuon movement”.[7] Mr. Saroeun answered that he had said that, because his commander had told him that Svay hid a group of Vietnamese in the vicinity of Svay’s house.

After the first break, Mr. Koppe referred to the DC-Cam interview of Lan, who had also talked about the incident of the twelve Vietnamese soldiers, “tracks” that they found, and a meeting near Svay’s house Koh Nhek.[8] They followed them, but could not catch up with them. “When I got back, we heard that they had killed each other”. The witness answered that he was not aware of this, “because it was an internal matter”. He said that he was “simply instructed to prevent the escape”. They were instructed to “be on alert” to prevent their escape. Mr. Koppe asked whether he recalled following them to the Au Ten Stream. Mr. Saroeun repeated his previous answer. Mr. Koppe inquired whether Mr. Saroeun had any information as to whether Lan was still alive today. The witness answered that their districts were “only 100 kilometers away from each other”, but that his only source of information was through his commanders. If they did not tell him, he would not know. He did not know whether Lan was still alive today.

Mr. Koppe referred to Sao Sarun’s testimony of 30 March 2016[9], who had talked about a meeting in the sector, during which he had been informed that the Vietnamese came into the area nearby Kham Phoun’s house, where they were given food. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether this was something he had heard as well, which the witness had not.

Mr. Koppe moved on and inquired about a meeting between Son Sen and the commanders of 920 of 07 September 1976. [10] During this meeting, Son Sen had said that

- we won’t be the ones who make trouble

- but we must defend our territory absolutely

- if Vietnam invades, we will ask them to withdraw and if they do not withdraw, we will attack. our direction is to fight both politically and militarily

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether this information was distributed to the soldiers through his commanders, which the witness denied. Mr. Koppe asked whether he was aware of Vietnamese armed incursions into the territory of Democratic Kampuchea in 1976, 1977 or subsequently. “I knew about the Vietnamese incursions into Cambodian territory. It happened in 1978. There were many Vietnamese forces, but they did not come through the area I was in charge of’”. They arrived in Koh Nhek. “In 1976, 1977, there was not a problem yet”. They only arrived in Cambodia in large numbers in mid-1978.

He said that Sao Sarun would have been more aware of the situation, since he was in a superior position.[11] With this, Mr. Koppe finished his line of questioning and the floor was given to the Co-Prosecution.

Buddhism under the Khmer Rouge

Nicholas Koumjian wanted to know what happened when Mr. Saroeun was defrocked. He replied that he was a monk, but also worked “like ordinary people”. When he was defrocked, Angkar assigned him to work in the commune. He was forced to disrobe after 17 April 1975. They told him that there would not be any monkhood in the regime anymore. All monks in his district, including chief monks and novices, were defrocked. “In your heart, did you remain a Buddhist during the regime?” he was asked by Mr. Koumjian

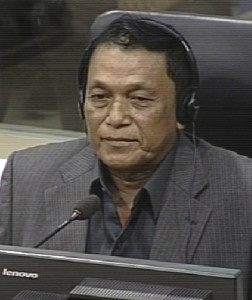

Witness Chin Saroeun

“Yes, I was very regretful, because when I entered the monkhood, I did not think of ever leaving it”. Moreover, “I still loved Buddhism very much”. At that time, they were not allowed to light incents or practice religious rituals. “It was completely different from nowadays, when we see religious practices conducted for dead people”. He was a commune assistant after leaving the monkhood. Chhin came to receive the witness’s force. “Based on my understanding, the regime did not allow religion. And they used labor without respecting the labor rights as we do right now. They used us to build dykes and dams”. They were given porridge to eat. “As I said, there were no rights for labor and religion. And we were all required to work”.

The Principle of Revolutionary Affiliation

He said that “When the husband committed wrongdoings, the wives and children would be in trouble”. When Mr. Koumjian asked about the principle of revolutionary affiliation and how it affected people’s lives, Mr. Koppe objected and said the witness could not give information on how it affected other families. When Mr. Koumjian repeated the question and Mr. Koppe objected again, Mr. Koumjian directed his words to the defense counsel: “Perhaps we should strike all the testimony of this morning”, since counsel had asked questions about many different areas that were not where the witness was stationed.

Mr. Saroeun replied that he did not know much about this and did not know the policies of the regime. Mr. Koumjian read an excerpt of his statement, in which he had mentioned the principle of revolutionary affiliation, and explained that all members of families would be regarded as enemies if one of them was thought to be an enemy.[12] Mr. Koumjian inquired what made him say this. He told the court that he hated the regime, because all family members would be “in trouble” when one of them was arrested. Mr. Koumjian asked whether he ever saw such an incident. Mr. Saroeun gave the example of a people close to the border, who confessed to the government in Siem Reap, and whose family members were later arrested and detained. They were detained at Au Keng Kang.

Mr. Koumjian inquired whether he ever drove the vehicle with the plate number 05 on it. He replied that the vehicle stationed at the border had the plate number 502 on it and belonged to Unit 502.

When people saw this vehicle “they would immediate learn that there were problems in the district”. The people who were concerned could not escape. “People were afraid when seeing that vehicle”. This vehicle was “used to pick up someone who had committed an offense”. Hence, “people were afraid when seeing that vehicle”.

He did not know much about the arrests of civilians, since he was stationed at the border. This would be beyond his knowledge, he said. Asked whether many soldiers were arrested, Mr. Saroeun told the Co-Prosecutor that he did not know much about events in other districts. “I focused on working and accomplishing the tasks I was assigned to”. His unit was not involved in arrests. They would only be assigned to deal with issues at the border.

Ethnic minorities in Mondulkiri

Mr. Koumjian sought information about the population in Mondulkiri. He recounted that the majority of the population in Mondulkiri were ethnic minorities, belonging to eleven groups, including the Jarai, Loeu, Tompoun, and Phnong (or Pnong).

Only when his group arrived was there a large number of ethnic Khmer. “They were all gathered to live in Koh Nhek”. Mr. Koumjian asked whether these minorities also lived on the Vietnamese side of the border. Mr. Saroeun answered that he did not know. In the period prior to the war, these minorities lived in their villages and worked on plantation. “However, during the three year period, Angkar gathered them all and made them live in Koh Nhek”. Mr. Koumjian inquired whether he remembered that in 1976 or 1977, members of a group called FULRO came to Mondulkiri. Mr. Saroeun answered that he saw them in 1976, 1977 and early 1978. “The forces actually came from the Vietnamese side”. He did not know who led this movement, but it included ethnic minorities, such as the Jarai. Mr. Koumjian asked whether he would sometimes refer to them as Vietnamese soldiers. “Initially, when the FULRO forces arrived at the Vietnamese border, we assumed that they were the Vietnamese forces. We did not know that FULRO was part of a resistance movement”. When they contacted Kham Vieng, the latter told them that they were part of a resistance movement with a plan to liberate their country.

He said that his commander was telling him the truth about the twelve people who came to Cambodia. “That’s what he disseminated, and later on Vietnamese troops came to Kampuchean territory”. Moreover, other people told him about the same incident, which led him to believe that the information he had been given by his superior was correct. His commander did not tell him that Vietnamese forces killed Svay, but told him that the Vietnamese group was affiliated with Svay and that he was killed by someone else. He did not know details about the incident, but only knew that Svay “concealed twelve Vietnamese near his house”.

Mr. Koumjian read an excerpt of Lan’s statement, in which this person had talked about Svay’s relation to the Vietnamese and FULRO.[13] Mr. Saroeun answered that his commander had not said anything about FULRO when talking about Svay.

Minorities

Mr. Koumjian referred to the speech by Son Sen that Mr. Koppe had referred to as well.[14] He asked whether the witness was aware of internal conflicts going on in Vietnam at the time that Son Sen mentioned with refugees coming over to Cambodia. Mr. Saroeun replied that he had to defend the border and that he knew that the Vietnamese force entered Cambodian territory in 1977 or 1978.

Mr. Koumjian referred to Chapter 10 of the book Khmer Rouge Purges in the Mondulkiri Highlands, which elaborated on the arrests of members of the Mnong minorities, because they had visited relatives in Vietnam.[15] He never saw any of these people belonging to the minority cross the border. Only in 1978, people from Vietnam came into the country. The regime at that time “sent them back”, but he did not know where to.

Turning back to the topic of FULRO, Mr. Koumjian asked whether members of FULRO and highlanders were sent to re-education camps.[16] He asked whether he ever heard any members of ethnic minorities talk about persecution that their relatives suffered from in Vietnam, which the witness denied. He confirmed that he did not speak the language of the ethnic minorities, but some people in his unit interpreted for him.

Mr. Koumjian read another excerpt, in which it was said that FULRO members, after having fled to the forests, resurrected their forces and directed them against Hanoi and sought support by the Khmer Rouge. Ieng Sary said in 1979 that FULRO approached them for cooperation to receive guerilla training, for example. Mr. Koumjian asked whether he received information about the agreements and negotiations between the Khmer Rouge and the FULRO. Mr. Saroeun replied that he was not aware of the relationship between them. “What I knew was from when I met them and asked them, and they told us they were part of FULRO, and they were arrested and sent [to Koh Nhek]”.

Next, Mr. Koumjian showed a photo to the witness that showed Binhy Ban, who wore a badge on his uniform.[17] He neither recognized the picture nor the badge. He said that the symbol was similar to the one used by FULRO.

Mr. Koumjian then referred to the testimony by Bun Loeng Chauy, who had said that Svay was accused of hiding the Vietnamese.[18] It was said that Svay had “a relation” with FULRO. He did not know the ethnicity of the twelve people. Svay was Jarai-Tompuon. His commander did not say whether the twelve people were FULRO, “he simply said they were yuon”. [19]

Mr. Koumjian then referred to a telegram to Son Sen, who they believed was Brother 89, in which the Army of Chieu was mentioned. The witness did not know more about this. Mr. Koumjian pointed to another telegram, but the witness could also not shed more light on this.[20] Mr. Koumjian referred to another testimony.[21] The witness did not know more about this. Mr. Koumjian pointed to another telegram to Office 870, in which the arrest of two yuon was mentioned.[22] The witness stated again that he had not received any information on this.

He was not aware of what happened at the Security Center in Phnom Kraol, even if it was not far away. He heard about this center, but did not witness it with his own eyes.

Asked about the average age of the soldiers were. The witness answered that they were on average below twenty. They were mostly between 17 and 20 years old. They received instructions from their commanders that the war had ended and that they had to “rebuild [their] country”. At his unit, there was no punishment or sanction. If a mistake was committed, the person would be called in and “advice would be given to him to re-fashion himself”.

Mr. Koumjian asked about the S-21 executions from Mondulkiri and wanted to know why “all of these people from Mondulkiri were sent to Phnom Penh and killed”. [23] Mr. Saroeun answered that he had no more knowledge about Division 920 after having been transferred. At this point, Mr. Koumjian finished his examination.

Marriage

His national colleague Song Chorvoin asked when he was married. Mr. Saroeun replied that forced labor was difficult: “the life and condition was so miserable. […]. I was young and I was forced to work hard with little food provided”. When Ms. Chorvoin repeated the question, he answered that he was married in 1977. His commander asked him to marry: “He did not force me, but he asked me.” This happened also to other people in his unit. Sixteen other couples were arranged to marry on the same day. They were given beef and chicken, but no traditional wedding ceremony.

He went form Division 920 to Mondulkiri “to increase the population”. The plan for the Khmer men to marry the minority females there. They would bring fifty minority women to marry fifty Khmer soldiers. However, he married a Cambodian woman. There was no written instruction about this. He only knew that this plan existed in his unit, but they did not follow through with this plan.

Getting Settled in Mondulkiri

When leaving Kratie, they were put on a truck to Mondulkiri. They had to clear the road sometimes. It took them around one month to go to Koh Nhek in Mondulkiri. They had to build their own shelters there. They got up at 5 am and started with physical exercised. At 6.30, they had breakfast and at 7 am they started working. They built dykes manually, since there was no machinery. They had lunch at 11 am and resumed their work at 1.30 pm. At 5 pm, they had their dinner and resumed their work until 11 pm. “Some people could last only for up to ten days”. There was no light at night time. They had to put on fire to lighten the work site. “Sometimes we stumbled”. Hence, “we were over-exhausted from this manual work”. The food consisted of small portions. “They did not care whether we had sufficient food or not. The aim was to fulfil the quota imposed by Angkar”.[24] They did not have sufficient food to eat. With this, Ms. Chorvoin concluded her questioning and the floor was handed to the Civil Party lawyers.

Authority Structure in Mondulkiri

Civil Party Lawyer Ven Pov wanted to know why he had said that Mondulkiri or Sector 105 were autonomous. [25] Mr. Saroeun answered that it was because of the authority structure: the provincial governors would go directly to Phnom Penh and not to the zone level. Those people who were sent to Mondulkiri had “no tendencies” toward 17 April People. They were mostly peasants. Mr. Pov asked about his suspension he had talked about in his interview. Mr. Saroeun explained that he was suspended not because of any wrongdoings, but because of his physical condition instead. He did not receive any further training.

Mr. Pov inquired whether he heard of the term enemy and wanted to know who was considered enemy during the regime. Mr. Saroeun explained that this referred to someone who broke property, such as when someone broke a hoe. However, “no one was arrested or punished”. They would be re-educated instead, which gave raise to sufficient concern for them to be careful not to break anything.

Back to Marriage

He knew his wife before their marriage. “The story is like this: my commander, he liked me, so he recommended me to her. And he asked me whether I loved her. As for other couples, they were not treated like me. They were simply invited and they were asked to marry”. International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud sought leave to ask a few follow-up questions, which was granted. She wanted to know whether his wife was a soldier and who she was. Mr. Saroeun answered that she was in the mobile unit in his unit. She was also from Takeo like him. He confirmed that the other couples knew each other. “But they were not aware of who would be their spouse. They started to know on the exact day that the commander called them to marry”. There was one couple that disagreed amongst the couple, “but the commander asked them for a meeting to convince them, and finally they agreed to get married”. The woman wore “beautiful clothes”, but the men wore torn clothes.

Men and women who were invited to the wedding day “were not aware of their supposed spouse”. Moreover, “the purpose of marriage was to increase the population in the province”. As for the plan to marry Khmer men to women from minorities “it was to assimilate them”.

Ms. Guiraud then asked whether he was explicitly asked to have sexual relations on the night of the wedding. “Regarding the consummation of marriage, it was the affairs of two people. After we committed to our marriage, the unit chief gave each of the couples one house and the women would go to wait for the men at the house, and then there was an elder men who would lead the men who his supposed wife was waiting.” There was no one who observed them, he said.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Early adjournment

After the last break of the day, Judge Ya Sokhan handed the floor to the Defense Team for Khieu Samphan, who announced that they would not have any questions. International Co-Prosecutor suggested to have the trial management meeting this afternoon. Judge Ya Sokhan thanked the witness and dismissed him. He then adjourned the hearing for today. It will resume Monday, August 8, 2016, with a key document hearing. Tomorrow, a court management meeting relating to the key document hearing will be heard from 1.30 pm onwards, part of it in camera.

[1] E3/10578.

[2] E3/10578, at 01249759 (EN), 00042520 (KH), 01249782 (FR).

[3] At 01249753 (EN), 00042514 (KH), 01249777 (FR).

[4] At 01249767 (EN), 00042526 (KH), no French.

[5] At 01249763 (EN), 01249784 (FR), 00042523 (KH).

[6] At 01249763-64 (EN), 00042522-23 (KH), 01249783-84 (FR).

[7] At 01249765 (EN), 00042524 (KH), 01249788 (FR).

[8] E3/7822, at 00667375 (EN), 00665353 (FR), 00229230 (KH).

[9] E1/411.1, at 09:28.

[10] E3/799, Minutes of a Plenary Meeting of the 920 Division, at 00184781 (EN), 00083160 (KH), 00323917 (FR).

[11] Sao Sarun’s testimony, 30 March 2016, at 09:09.

[12] At 00042517 (KH), 01249779 (FR), 01249757 (EN).

[13] E3/7822, at 00229231 (KH), 00665354 (FR), 00667377 (EN).

[14] E3/799, at 00184780 (EN).

[15] E3/1664, Khmer Rouge Purges in the Mondulkiri Highlands, p. 98, 00397671 (EN).

[16] Ibid, p. 117, 00397684 (EN).

[17] E3/8639.3944.

[18] March 28, 2016, E1/409.1.

[19] E3/1022.

[20] E3/1204.

[21] E1/399.1, at 11:28.

[22] E3/877.

[23] At 00397712-26 (EN)

[24] E3/10578, at 00042520 (KH), 01249757-58 (EN), 00114276 (FR).

[25] E3/7960, at 00851665 (KH), 00450295 (EN), 00763898 (FR).

Featured Image: Witness Chin Saroeun (ECCC: Flickr).