Civil Parties Tell Of Loss of Family Members

Today, three Civil Parties took their stance in front of the court, one of them via audio-visual link. They told the court about the suffering they had undergone during the time of the Khmer Rouge in relation to Case 002. All of the statements circled around the loss of family members in relation to security centers and purges.

First Civil Party: Che Heap

Presiding Judge Ya Sokhan

All parties were present, with Nuon Chea following the hearing from the holding cell. Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn was still absent and replaced by Judge Ya Sokhan, who announced that today and Monday Civil Parties would be heard in relation to Phnom Kraol, Au Kanseng, Tuol Sleng, and internal purges (2-TCCP- 275; 2-TCCP-1047; 2-TCCP-1049 [via audio-visual link from France]). Tomorrow, key documentation presentations would be heard by the Co-Prosecution and Civil Party statements would continue on Monday.

Judge Sohkan reminded the parties that the civil party statements should relate to a general statement of harm and suffering and should be related to the facts in Case 002/02, but that it would not constitute a breach of the right to a fair trial if the statement fell outside the scope of the trial in parts, as long as there was an opportunity to object.[1]

National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang sought clarification about this statement: he said that from what he knew, Civil Parties could make the statement in relation to facts regarding Case 002 in general, and not only Case 002/02, while Judge Sokhan’s explanation seemed to indicate that only facts in relation to Case 002/02 would be admissible. Judge Sokhan reiterated that the facts related in general to the case.

Civil Party Che Heap was born on 1 February 1961 in Kampong Svay District in Kampong Thom Province. Judge Sokhan informed him that he could make a statement in relation to physical, emotional and material harm which were the direct results of crimes that he had experienced.

Civil Party lawyer Hong Kim Suon put questions to the Civil Party and inquired about the background of the Civil Party. Mr. Heap lived in the Khmer Rouge controlled region in Kampong Thom before the fall of Phnom Penh in 1975. They were eight siblings (4 sisters and 4 brothers). After the fall of Phnom Penh, they were instructed to return to their native village, but not all of his sibling returned: Three of his siblings had become part of the Khmer Rouge movement beforehand. “A number of my siblings went missing, including my elder siblings-in-law”. The ones who went missing were the following: Che Heng and his wife, Houl Nong, Che Toch, and Che Mon.

Che Heng

Civil Party Lawyer Hong Kim Suon

Mr. Kim Suon wanted to know where Che Heng lived after 1975. He replied that he lived in Phnom Penh after 1975 as a member of Division 310. He went to visit the village when Phnom Penh fell. He got married and returned to his native village to take one of his siblings to live in Phnom Penh in a children’s unit. On a third trip his older brother took Mr. Heap with him to live in the children unit of Division 310. This unit was part of the Central Army and stationed in Kampong Speu. Two of his siblings who went missing were called Che Toch alias Heang and Che Mon. Che Toch was part of a logistic battalion of the Division 310 office. His father had told him that Che Heng left in 1970 to join the revolutionary movement.

In Phnom Penh he lived in various locations, but longest near the Calmette Hospital near Sra Chok. He did not live with his older brother, because the Civil Party was in a children unit at the time.

As for the daily tasks of his brother, he said that he saw him using a typewriter in his office. “And I saw a lot of books in his office”. Moreover, he remembered that his brother had a gun.

One of his brothers asked another brother to “go back home”. He saw his brother with his typewriter. Later, Ta Horn[2] told him that his brother had disappeared. Another man saw Mr. Heap and said

“oh this is the brother of a traitor”.

Thus, Mr. Heap tried to hide his biography: when he was asked to write a new biography, he tried to hide his relation to his brother, since the latter was seen as a traitor. A number of other children from Division 310 also disappeared. He did not see his brother when he looked for his brother. Even his room was closed and locked.

When he met Ta Horn, he told him that his brother had been taken away on a truck. Ta Hao was a truck driver. When getting petrol, Ta Horn met his brother, who told him to take care of his family. Ta Horn had told him that Hor and Voeung, who was the deputy of the division, were involved in the arrest of his brother.

He was asked to join a meeting in 1975, and someone told him that Oeun was the chief of the division, Voeung the deputy and that the member was Ol. Ta Horn told him that his brother had been taken south, and that people who were taken south would never return.

There were documents of Tuol Sleng Prison now, he said. Mr. Kim Suon showed a photograph of prisoner Che Heng to the Civil Party.[3] There was a technical error, so the photograph could not be displayed on the screen.

He recounted that he heard about the news of his brother on the radio broadcast, but did not have money to travel to Phnom Penh. Later, Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) brought his brother’s photograph to his village. Upon seeing the photograph, he “wept the whole day”, because his brother Che Heng looked skinny – Mr. Heap said that his brother must have suffered a lot. The photograph was then shown to the Civil Party, who confirmed that it was his brother.

Che Heng’s Wife and Children

Che Heng’s wife was in the sewing unit in Tuol Kork. Ta Horn told him that when he was transporting rice, he saw that his wife and other cadre’s wives were taken away on a truck to a pagoda. Ta Horn is still alive today, Mr. Heap said. Based on Ta Horn’s account, Che Heng’s wife and children were also arrested not long after Che Heng’s arrest. His brother had one daughter and another unborn child. He received no news from them even when returning to their hometown in Kampong Cham.

Ta Horn told him that wife and children would be arrested when someone was arrested.

Che Toch and Che Mon

He was in the children unit together with Che Toch and Che Mon initially. Men and women were separated. Che Toch and Mr. Heap stayed together initially. They were asked to make biographies. He said to a cadre called Da that he was never a policeman or soldier.

Later, his brother Che Toch was taken away. They were looking for Mr. Heap later, and he told him that he was not a brother of Che Toch and that they were merely cousins. A few days later, they were called to a meeting with 17 attendees. Those who were called out by name had to go to a different unit while those who were not called were staying in the same unit. Mr. Heap confirmed that his brother Che Toch was arrested. His sister Che Mon was still in the children unit at the division. After the rice cultivating season, she returned to the children unit, while his brother Che Toch had been taken away already. This was around 1978.

Civil Party Che Heap

Che Toch was with Mr. Heap when he was arrested. Mr. Heap was transferred to another unit, which was close to where Che Mon was located. He helped cleaning wounds from soldiers who came from Kampong Cham battlefield.

In total, five siblings disappeared: Che Heng and his wife, Huol Nong, Che Toch, and Che Mon. None of them returned, including his nephews and cousins.

“I felt so [much] pity for them, that’s why I came here to give a statement of harm and suffering of my [family]”.

He went to testify in court, “because my brothers sacrificed a lot to the struggle, and still they were arrested and killed. That was very unfair to them, because they contributed and sacrificed a lot the struggle”.

He said that he could not afford to hold a ceremony for their siblings. As for the impact

“of course, you can ask my surviving family members. Every time [we think about it], our tear shed.”

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Arrests of cadres

After the break, the floor was granted to the Co-Prosecution. Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde asked whether Oeun and Voeung from Division 310 were arrested. He replied that Oeun was replaced by Ta Nho. He did not know how Ta Oeun disappeared, but said that he was also arrested. As for the reasons of the arrest, he recounted that they said that they had attempted to rebel and that they were sent for re-education. He could not remember when the arrest took place.

Ta Horn came to his older brother’s office and told Mr. Heap that his brother had been arrested. From that day onward he tried to hide his biography. Sometimes they were asked weekly, and sometimes once every two week.

“I lied in my biography.”

Senior Assistant Prosecutor Vincent de Wilde

Mr. de Wilde inquired whether the date of his brother’s arrest, as indicated on a document, 12 February 1977, refreshed the Civil Party’s memory.[4] Mr. Heap replied that this was accurate. He said that it was likely that his brother’s arrest was related to Oeun and Voeung’s arrest. During a meeting, they were told that they could not return to their lives after joining the army.

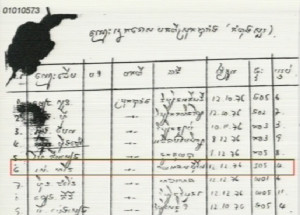

Mr. de Wilde then pointed to a list entitled The Names of the Prisoners Who Were Arrested on 12 May 1978 and highlighted number 68.[5] Mr. Heap said that he did not know the exact day that he was killed. Mr. de Wilde then said that this name also seemed to appear on the OCP Revised Prisoners List and on the OCIJ list. Moreover, Heng’s wife, Vorn Sroeun alias Ny also appeared on the list.[6]

As for the date of the arrest, he could remember that Ta Nho became in charge of the division when Mr. Heap was transferred to live in Tuol Kork. They had to watch a movie at Olympic Stadium. At this point, his unit chief had already disappeared. Messenger Kroeung was sent to his unit, and “when he arrived, I worked hard”. Kroeung told them that they would be transferred elsewhere. They were given uniforms at the division headquarters. There were different trucks and they were told that they would be transferred to another division. When they arrived there, they were housed in a building made of concrete. Subsequently they were called for a meeting, during which they were asked whether some of them were not hardworking. Some of the people during the meeting some said that others were lazy. This was when he realized “what would happen if I was lazy”. He knew three people who were said to be sent to Pochentong Airport, but they disappeared since that time. He was said to be attached to soldiers from the East Zone.

Mr. de Wilde referred to the Civil Party’s Written Record of Interview and wanted to know whether the number of 50 people who disappeared was correct.[7] He replied that it was in Krang Leu to the West of the airport worksite. Judge Sokhan informed the Co-Prosecution that the time had run out and the floor was given to the Nuon Chea Defense Team.

Meetings and Divisions

Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe asked whether the Calmette Hospital where he was stationed was close to Wat Phnom. He answered that the military hospital of Division 310 was not there, but was based in front of Ta Voeun’s house next to the Calmette Hospital. He went to study sessions to the north of Wat Phnom, where senior cadres were arrested. They spent around one month for the study session. The meeting took place at the 310 headquarters in Tuol Kork before the arrest of the commanders of the division. He did not know where the radio station was located. He did not know how many battalions there were in the division. After he left the children unit, he knew only about the people in his unit and had no knowledge of other units.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether Battalion 306 commanders Ta Yim and Ta Ban rang a bell. He confirmed having heard of their names. At the meeting, they announced the names of the people who would speak. Thus, he had no knowledge about the people. When Mr. Koppe inquired about the ranks of Ta Yim and Ta Ban, he repeated that he had “no full knowledge” of the structure of the division.

Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Mr. Koppe asked whether it was correct that his brother belonged to the North Zone, as he had said in his statement.[8] Mr. Heap confirmed this. As for Koy Thuon, Mr. Heap recounted that he was in charge of the Zone. He did not know what exactly his brother was accused of doing. Mr. Koppe asked whether he had heard of an attempt to attack the radio station, Pochentong Airport, or to stage a coup d’état against the CPK. He did not know the exact number of the people who were arrested in the division. Asked about secret storage of weapons, Mr. Heap answered that he had never seen any. Mr. Koppe turned to his last question and inquired whether he had heard of Division 310 combatant Sem Huon, who had also testified in court, which the Civil Party denied. Nor did he know Khorn Brak. With this, he finished his line of questioning. The Khieu Samphan Defense Team did not have any questions for the Civil Party.

The floor was then granted to the Civil Party to make put questions to the accused.

Questions by the Civil Party

“First, I’d like to ask the accused […] as to the reason why my elder brother who sacrifice himself to join the resistance until it succeeded, why was he arrested, tortured and executed […] and why my younger siblings were also arrested and executed?

He then posed a second question:

“Why we had to eat communally, to live communally, why cooperatives were established and why soldiers were not allowed to visit their native village”

Lastly, he asked

“Why such regime was established, why there were no longer pagodas and money circulation and why freedom was prohibited. No money changes hand, no market, no pagoda to go to during the regime, and why was that?”

Civil Party Phoung Yat

He pointed out that he had several questions to put to the accused before he came to court, but could not remember them now. Judge Ya[9] The presiding judge then dismissed the Civil Party and ordered the court assistant to usher in the next Civil Party.

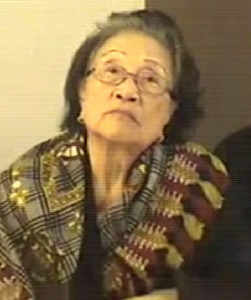

New Civil Party: Phoung Yat

National Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang

Phoung Yat was born on 15 April 1960 and lives in Krala District in Kampong Siem Province. National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang then started putting questions to the Civil Party. She lived with her parents before the fall of Phnom Penh and was with his father. She was separated from his siblings and her older sister Phoung Im was asked to go to Phnom Penh. She did not know about her fate and heard that she was arranged to marry and that she was working in a sewing factory. She did not hear from her again afterwards. She heard that her siblings died at Tuol Sleng and saw their photographs displayed there. An S-21 photograph of a person was shown to the Civil Party. She said that it was the photograph of his sister Phoung Im.

She recounted that his sister was sewing clothes, while his brothers were collecting palm sugar to sell in Kampong Cham. “They loved me all very much”. As for his feelings towards his sister, he said that “I loved her very much”. She took care of his siblings and him and took them everywhere. He saw a photograph at Tuol Sleng. She deducted from the photograph that she was “severely tortured”. “You could see that through her eyes.”

When she saw her photograph at Tuol Sleng:

“I was very sad. I wept to the point that I almost lost consciousness”.

At this point, Judge Ya Sokhan adjourned the hearing for a break.

Arrests of Siblings

After the break, Mr. Ang referred to a document that showed that Phoung Im was executed on 8 December 1978.[10] He inquired whether the Civil Party had lost any other relatives during Democratic Kampuchea besides her sister. Ms. Yat replied that she lost Phoung Im, Phoung Phon, and Phoung Phen, who joined army at Svay Teap ; Phoung Ven was in the economic section and rode motorbikes to visit them a few times. He told his parents that they should not write letters to him, because he would be transferred to Phnom Penh. Since then, they lost contact with him. Phoung Phen joined the army at Svay Teap and had disappeared since then.

National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Seng Leang

Next, a photograph was shown on the screen.[11] The Civil Party recognized her older brother Phoung Phon. Mr. Ang referred to another document, which showed the name Phoung Phon.[12] Ms. Yat recounted that she saw her sibling’s photograph at Tuol Sleng. She said that she was “terribly sad” and that they seemed to have been beaten up. “I miss them. I think that if all of them were still alive, it would be very great for us, for reunion during the Pchum Ben ceremony. But every time during Pchum Ben Ceremony, we feel very lonely”. She went to the pagoda during Buddhist holidays and brought food to be conveyed to the soul of his siblings through the monks.

As for her personal suffering, she recounted the living conditions while working. If she could not fulfill the assignments, she would be beaten. “I was very tired and sick, because I only ate the watery porridge. I had no energy to work”. One sister, who is still alive now, was arranged to get married. She fled over the rice field and was chased by two men. They searched for her, but could not find her. Thus, she survived until today.

She had a Cham friend who was called Khas. At night time, she was called out; “The next day, they gave me the scarf of Comrade Khas.” She did not want to accept the scarf, but was threatened and finally accepted the scarf. This happened in Koh Svay Village.

The floor was granted to the Co-Prosecution. Mr. Leang asked about the person who told him that a sibling had gone to Phnom Penh. She recounted that a person called Reyt had told her mother in 1979 that the Civil Party’s sister had worked with her in Phnom Penh. The person did not tell her mother anything else. The person told her mother that the person was a cadre in Phnom Penh, while her sister was at a sewing unit. The person did not say the name of her sister’s husband. She had received no news from her sister later.

She did not know what Phoung Thon’s tasks were and only knew that they joined the military. She never saw them again. Only Brother Ven visited them again in 1975, but disappeared afterwards. She did not know what the fate was of her brother either.

Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Liv Sovanna

Mr. Leang then referred to a few documents that seemed to indicate that Phoung Im was brought into S-21 in December 1978.[13] As for Phoung Phon, Mr. Leang showed a few other documents that related to his arrest.[14]

Her sister fled when the marriage was arranged for her, because she was afraid to be killed if she refused to marry the man she did not like.

The floor was granted to the Nuon Chea Defense Team. Mr. Liv Sovanna said that the Civil Party had told in an interview that Phoung Penh had been a mechanic, while he had said today that he was a soldier.[15] The Civil Party replied that she had heard that he first fixed generators and was recruited as a soldier later on. His brother Phoung Ven told him about her brother becoming a soldier in around 1975 or 1976. Mr. Sovanna probed further on the issue. Ms. Yat replied that people in the village told her that he became a repairman for generators in his native village, while her brother told her that her brother became a soldier. Mr. Ang interjected and said that the timeline was consistent and not inconsistent as claimed by the defense team.[16] Mr. Sovanna insisted that the timeline was inconsistent, but moved on. Mr. Ang again pointed out that the timeline was not inconsistent.

Mr. Sovanna asked whether each photograph was accompanied by their names. She replied that she could not read it properly, but that she recognized them clearly on the photographs. MR. Sovanna asked: “How did you recognize your brother?”. She replied that they had the same facial expression and lips. Her brother looked the same, except that her brother was thinner.

The sister who fled survived, because the villagers hid her. She did not attend any marriage ceremonies, because she was not allowed to do so.

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn

The floor was granted to the Khieu Samphan Defense Team. She spoke to her sister about the marriage when she was in a kitchen. The village chief was called Ta Heng. Her sister told her not to tell anything to anyone else, because she would be arrested and killed otherwise. The village chief agreed to hide her sister. After a few questions about her relatives, Mr. Sam Onn concluded his line of questioning.

The presiding judge then gave the Civil Party the opportunity to put questions to the accused:

She asked

“After they won the war against the Lon Nol regime in 1975 or 1976, why my elder siblings were taken away and killed. That’s the only thing I’d like to ask […]. They liberated the country for them, and how come they were taken away and killed?”

Judge Ya Sokhan informed the Civil Party that the accused exercised their right to remain silent, thanked her and dismissed her.

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud requested to have the break at this point, ten minutes earlier to the foreseen time, so that the Civil Party could be heard via video-link continuously. The request was granted.

New Civil Party: Ros Chuor Siy

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

After the break, presiding judge Ya Sokhan told the court that 2-TCCP-1049 would be heard now via audio-visual link from France. Civil Party Ros Chuor Siy was born on 20 September 1938 and lives in France. International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud then started putting questions to the Civil Party. Her husband Ros Sarin had disappeared. Ms. Guiraud read an excerpt of the Civil Party’s statement, in which he had said that they returned to Cambodia after the liberation of the country.[17] She asked how the disappearance had affected her life.

“My family and I returned to Cambodia on 6 August 1976. When we arrived at Pochentong, we were disappointed, because I did not see any families or people coming to receive us at the airport. When we travelled along the road, it was quiet. I felt worried. I was sad all the way until we were dropped at Office K-15. At Office K-15 I saw friends, especially two elder men, whom I met a few months before he returned to Cambodia. I saw them – their physical bodies were very thin and they wore old torn clothes and their appearance looked very upsetting to me. When they saw us, they smiled drily at us, [and] through their facial experience I could see their suffering. A little while later, I saw my sister, who was also in the office. My sister entered the country six or seven months before me. She also smiled at me, but that was an usual smile. it reflected pain and suffering in her. Immediately when I saw her, I asked her whether she met out parents and our relatives. She shook her head and said that she did not meet any one of them.”

Ms. Siy then recounted how she was relocated to another location.

“I was very sad. I never thought that my country would plunge into that situation of perpetual quietness.”

She then told the court how she was separated from her family.

“As for my family, which included five members, and each of us carried luggage of clothes, we could not get inside that small car. The head of the office told us that some of us would go later on. Later on I saw a person called Chhin Leung, whose name also appeared later on at Tuol Sleng

. My body trembled. I thought back to the time that if we could fit into that vehicle then the five of us would have been put into Tuol Sleng. However, this information I learned later.”

Her family was relocated again in mid-November 1976, namely to Boeng Trabek.

“There, the physical appearance of my husband became worse, he became even more emaciated and his health got worse, due to insufficient food”

She continued by explaining how she was separated from her husband, worried about him, but thought at first that she would see him again.

“In around mid-December 1976, while we were in the middle of a political study session at Boeng Trabek, my husband rushed to me to tell me that he was assigned by Angkar to perform a duty. I asked where he was assigned to and he told me that it was a secret and that Angkar did not tell him where he would go to. Before he left, he advised me to work harder and to look after myself and to look after hour children. He said don’t worry and we’ll see each other again soon. […] And I expected to see him again soon. At that stage, I was so worried since he was separated from me. I felt so lonely. However, I also had an expectation that he would be assigned to work in a new place and that he would be fed sufficiently and that the food there was more abundant than what we had and that the work would not be harder […]. However in reality it was different. His last words that we would meet again never realized. It had gone with the wind.”

She also told the court how she was told that she did not have to worry and would see her husband again.

“I had hope again upon hearing that and I kept on waiting and waiting while I was working. And every time there was a movement of vehicles entering the camp I tried to see whether my husband returned. I kept waiting and waiting, but in my mind, I became more worried.”

In February 1977, she and her children was relocated another time, which worried her more, “because I felt that [there] would be put even more distance between my husband and I.” At this point, she still believed that her husband was working at Pochentong, since he had formerly been the director of Pochentong airport before going to pursue his doctoral study in France.

“I tried to work as hard as other workers and tried to never express my sorrows while I was working. Sometimes while I was clearing glass […] I heard the sound of a plane flying over. And upon hearing that my tears dropped, since it reminded me of the time that we were together that we were on a plane together.

At this time, she worked at Dey Krohom and upheld hope that she would see her husband again, since other people were called and it was said that they would be reunited with their husbands. “I felt happy for them, since we believed that they would be reunited with their husbands. And I did not know when my turn would come […] I felt rather hopeless, because some people were sent to reunite with their husband while I was still waiting for my husband to return.”

Civil Party Ros Chuor Siy (via audio-visual link)

She asked the director of Dey Krohom Camp when she would be allowed to meet her husband again, but received the same answer that she would reunite with him eventually.

“I kept on waiting and waiting. And the concern and worry remained with me all the time. Once in a while at Dey Krohom Camp, a vehicle would arrive with some people, and every time I would feel excited that I would see my husband. My children were also anxious to meet their father, but every time when everybody got off the vehicle, there was no sign of my husband. The worry lingered on with me constantly.”

Ms. Siy then recounted how her younger sister contracted malaria while she was pregnant and how this gave rise to worry. She delivered the baby with an operation. At this time, her youngest daughter “secretly ran to see me”. Her daughter brought her fruit and food, since children in the children unit were given more food.

In 1978, they were transferred back to Boeng Trabek, which made her think of the time that she was sent there with her husband.

“I questioned myself, how could we have left France, where we lived in a comfortable position?”

She also grieved being separated from her parents, too. “How come my life become so miserable?”

Living After Disappearance of Husband

She then told the court that she gained strength through her children. “I was living with my three children like a widow and hopes to see my husband disappeared. I tried to collect myself to do everything for the sake of the future of my children.”

Lastly, she remembered how she visited the Tuol Sleng Museum for the first time.

“While I was there visiting each room, seeing those torture instruments, I saw a lot of things there and I do not want to see them again. And finally I went to a room where photos of prisoners were displayed. That was the time that my pulse was raising. I tried to screen every single photo displayed. I saw amongst those photos some people that I knew. Finally I saw a photo of my husband. It was there. I wanted to cry out loud. I almost fainted.”

She continued:

“However, there was a voice telling me not to cry and to collect myself. I then regained my strength. From that day onward I told myself that I could not live in a country in such a condition and that I had to do my best for the future of the children, since they no longer had a father and they relied entirely on me as their mother. I had to try everything in order to feed my children. Everybody looked sad after the visit to the place and in particular I became worse. I no longer had any hope. And I made my decision then that I had to migrate somewhere, or to France.”

Excerpt of an S-21 Prisoner List

Due to bad quality of the audio-visual stream, Ms. Siy could not be understood and interpreted anymore. Instead, International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer suggested to direct a few questions to the Civil Party. A document was shown on the screen that showed eight photographs men.[18] She said that her husband was the second man from the left on the second row. Ms. Guiraud showed another excerpt of a list.[19] Ms. Siy confirmed that it was her husband’s name Ros Samrin. Ms. Guiraud asked what the information meant to her that he entered S-21 on December 1976, specifying that this was a few weeks after she had last seen her husband. Ms. Siy replied that she had no more hope when she saw that he had been at S-21, “because it was the place where people were brutally murdered”. With this, Ms. Guiraud finished her line of questioning and the floor was handed to the Co-Prosecution, who inquired about her stay in France. Ms. Siy said that she met him in 1972. Her husband received a scholarship from the Phnom Penh government to pursue his studies and acquire a PhD in France. He worked with AirFrance and AirCambod. They returned to Cambodia, because they hoped that Cambodia would be peaceful again after Phnom Penh fell. They returned to help rebuilding the country. Her husband did not meet Ieng Sary personally. When they disembarked the plane, they had no right to move anywhere. They had no freedom to go anywhere outside the office, which was more like a detention center. Her husband attended a meeting at Boeng Trabek. They only met the chief in charge of the place. Some other people were taken away together with her husband. Mr. de Wilde referred to the book by Ong Thong Hoeung, who had referred to a few people.[20] She said that she remembered the most Choeun Meng Mao.

Mr. de Wilde referred to an S-21 list that was entitled Names of Prisoners Who Were Smashed on 18 March 1977.[21] This list showed the execution date of her husband as being the 18th of March 1977. Mr. de Wilde asked whether she had already had that information before she went to S-21. She said that she did not understand the question. She confirmed that he was called Mao by some of his friends. She did not know who else had been executed.

With this, the Nuon Chea Team was granted the floor. Mr. Koppe asked whether she knew a person called Suong Sikhoeun. She said that she had heard of the name but did not know the person. Mr. Koppe read an excerpt of a statement, in which Suong Sihkoeun had said that her husband collaborated with the Lon Nol regime and could be classified as a progressive nationalist.[22] Mr. Koppe asked whether her husband was a supporter of Sung Ngoc Tan. She replied that she did not know about his past. He worked with the Lon Nol government. Mr. Koppe asked whether she knew Hor Namhong, who was Minister of Foreign Affairs until April of this year and who had worked at Boeung Trabek. She confirmed this. Hor Namhong was the chief of Boeng Trabek office, she said. He divided the assignments amongst groups. He was not a prisoner. Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he had any role in sending her husband to S-21, which Ms. Siy did not know. Nor had she heard of him being accused of being “an accomplice” of Ieng Sary.

At this point, the floor was given to the Khieu Samphan Defense Team. Under a brief questioning of Defense Counsel Anta Guissé she said that she had heard that the secretary of Ieng Sary was called Sao Hong. She saw him one at Boeng Trabek.

Questions by the Civil Party

She was then given the opportunity to put questions to the accused. She said that she would have wanted to put questions to Ieng Sary.

“It seems that the Khmer Rouge Tribunal proceeded rather slowly, and as a result the accused died before he could be tried. It was Ieng Sary himself who went on a propaganda [trip] for Khmer expatriates [..] to return to Cambodia to rebuild our war-torn country. And he made that appeal to Khmer living overseas to return. I feel a bit relieved after I have made my statement. When I returned to Cambodia, my purpose was also to meet with my parents […] but I did not even know where they were buried, if they were buried at all. And my second purpose is to convey a message to the younger generation that they should learn from this experience”

She said that they should be wary of the methods used and not be deceived by politicians, who, she said, lied.

“Murderers can travel freely in the country, and some of those can even hold senior positions in the country. And this culture of impunity obstructs the peaceful living of the general population. That also put an obstacle to the safe movement of freedom and as a result, our economic situation does not improve. Tourists are scared to visit our country […]. And recently Doctor Kem Ley was murdered.”

At this point, the presiding judge informed her that the questions were to be directed to the two accused. She referred to the situation in 1975 where “Ieng Sary appealed to Khmer to return to Cambodia” under “the pretext of rebuilding the country”:

“Did they know that the majority of Khmer expatriates [were] killed at Tuol Sleng? And my second question to the two accused, that s Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, is this: you two held very senior positions in the leadership of Democratic Kampuchea regime. What is your view on the killing of millions of Cambodia people and what was your responsibility for that?”

With this, her testimony concluded. Judge Sokhan thanked her and announced that tomorrow, August 11, 2016, key document hearings would be heard from 9 am onwards.

[1] E315/1.

[2] This person was sometimes also referred to as Ta Hao.

[3] E3/647, at 00544248.

[4] E3/289.

[5] E3/3858, at 008837619 (EN), 00848743 (FR), 00009196 (KH).

[6] E3/342, at Number 908. E3/10604; E3/10266, page 12 (KH), 01016893; Nr. 7519 on OCIJ list and 11612 on the OCP list; E3/8663, at 00016193 (KH). E3/10431, at page 2.

[7] E3/9441, on page 5 (EN) and 6 (KH).

[8] E3/9441, at 00804120 (EN), 00804127 (KH).

[9] E421/1/2.

[10] E3/8555.

[11] E22/3397b, at 00594301 (KH).

[12] E3/1056, at 01019316.

[13] E3/10604, at index 2 of OCIJ Prisoner List, 31 March 2016; E3/8555; E3/342, at index 1, Prisoner List of S-21, at 00329929.

[14] E3/10604, at index 2 of OCIJ Prisoner List, at 00122434, at number 2623; E3/10506; E3/9845, at 001010228 (KH), at number 99; E3/2286, at 00091258; E3/42, at Index 1, OCIJ Prisoners List, at 00329929, at number 7666.

[15] D22/3397a.

[16] D22/3397a.

[17] E3/5040, at 00563643 (FR), 00807822 (KH), 00793826 (EN).

[18] E3/5040, at 00827825.

[19] E3/9853.

[20] E3/1713, at 00785804 (EN), page 140 00288019 (FR), 0031182-83 (KH).

[21] E3/2285, at 00873361 (EN), 00009182 (KH).

[22] E3/1716, at 00824620 (KH), 00290701 (FR), 00826569 (EN).

Featured Image: Civil Party Phoung Yat (ECCC: Flickr).