Segment on Forced Marriage Begins

Today, August 23, 2016, two Civil Parties gave their testimonies in relation to forced marriage, a segment that had started yesterday afternoon. The first Civil Party remained anonymous due to ongoing investigations in other cases. She told the court about forced marriage and an instance of rape by her unit chief. Civil Party Sou Sotheavy talked about her experience as a transgender woman during the Khmer Rouge regime and being forced to marry.

Rape

All parties were present, with the exception of Nil Nonn, who was replaced by Judge Ya Sokhan. 2-TCCP-274 was heard first, followed by 2-TCCP-224.

Civil Party Lawyer Hong Kim Suon

First, the Lead Co-Lawyers for Civil Parties were given the opportunity to continue putting questions to the Civil Party. Hong Kim Suon asked whether she was told about a marriage by anyone else before her marriage. She recounted that she was informed about her marriage a day before. However, on the wedding day, “the man was not the man who proposed to me”. A person called Om Phorn proposed to her before, but on the wedding day she was married to another man. He was called Nhean. She was instructed to stay at Ta Mounty Khnong. The couple was instructed to enter a room. The other newlywed couples stayed in other rooms. “I was not instructed anything, however, when I entered the room, my husband was there”. She remembered: “At that time, we didn’t talk much. He just slept with me. I was afraid. I resisted his advance. He was upset, so he went out of the room and informed his military commander.”

She resisted, because she did not like her husband. “He did not try to console me […]. He simply wanted to have sex with me.” Her husband reported the matter to his chief Comrade Phan. “He complained that I did not consummate the marriage with him. Then, Comrade Phan called me to see him”. This happened during the same night. She was called to a room. “When I was in the room, I was questioned why I did not consent to have sex with my husband.” Her husband was in the other room at the time. Comrade Phan then raped her. “He said that if he raped me and I shouted, then I would be shot dead. And after that warning, after that rape, that I had to shut my mouth and had to agree to live with my newlywed husband”. He used “strong words” while he raped her. “I didn’t dare to make any noise, because I was afraid that I would be killed if I made any noise”. She had a cousin called Heng Vanny, who refused to marry her husband once or twice. She was taken away and killed. Someone else was wearing her shirt the same day that she was taken away, because that other person had her cousin’s nametag on the shirt.

Her husband remained in the military unit, while she was transferred back to Unit 7. When the couple met each other every ten to fifteen days, they would consummate the marriage. “The guards monitored us”. She noticed the militiamen when she went outside to relieve herself. “Every time he came to see me, we had sex. But I did not really feel it was a husband-wife relationship. My husband did what he wanted to do.”

Being Pregnant

She gave birth to a child in late 1978. She had morning sickness after being one month pregnant. She felt exhausted and sometimes dizzy. “I had to find other things to eat, because I could not eat the given rice”. Her child did not move much during her pregnancy. She was not given any supplementary food. In the seventh month, she went to a hospital and was told that the baby was very weak. She had to continue working. Her husband was only allowed to visit her and the baby for a day or two after she had delivered the baby. A medic sent her to rest on a bed. A fire was made under the bed, but no one else came to assist her. The baby was very small, but there was no scale to weigh the baby. She was not given any clothes for her baby. She was given some when she went to visit home. The baby tried to drink the little milk that she had. Her husband came to visit her and brought her traditional milk to drink. She was allowed to rest for a week or a fortnight. Then, she was allowed to clear weeds and had to take her baby with her while working.

“When they came into Chamkar Leu District”, she fled to Kampong Thom Province, while her husband went elsewhere. She saw him only three years later. “They” referred to Vietnamese here. Her parents and the elder in the village tried to convince her to accept him when he returned. “Recently, my life became revitalized again, because my child has grown up and the organization has helped me with my psychology”.

At this point, he gave the floor to his international colleague Marie Guiraud, who asked about her relationship to her husband. She did not love her husband, because he was ugly. He was ethnically Khmer, but came from the north of Cambodia. He was disabled. She did not know whether he got injured at the battlefield. Ms. Guiraud then asked why she only spoke about the instances of rape today and had not included it in her Civil Party Application. She explained that “it only came to my mind now”. She confirmed that she was subject to two instances of rape: one by Phan and one by her husband. Her husband raped her around ten or fifteen days after Phan had raped her.

Follow-up

The floor was granted to the Co-Prosecution. Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak wanted to know whether she was a worker at a rubber plantation, which she confirmed. It was at Chamkar Andong. The chief was Cheang Soeung. Ta Sat was in charge of Montey Khnong (Or office Khnong, see yesterday’s blog). Mr. Lysak asked whether he knew someone called Chhim. She recounted that Ta Chhim replaced Ta Sat when the latter disappeared. He came from the east. This was a few months before the Vietnamese entered Cambodia. Her husband was part of the military at the time and they were based at the rubber plantation. The military unit Region 304 in Chamkar Leu was “relatively big”, she said.

International Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak

Mr. Lysak sought more detail about her cousin Heng Vanny: did this event take place before or after the Civil Party got married? She replied that it occurred before her marriage. She was accused of being part of an enemy network and subsequently arranged to marry. She refused and was taken away and killed. Her cousin was in a different village. The village was close-by.

Mr. Lysak read an excerpt of her Civil Party supplementary information form and wanted to know how she knew that her relatives died at S-21.[1] She said that she did not know first. People told her that her relatives had died there. She did not find her relatives there. Mr. Lysak referred to two people on the OCIJ S-21 list and requested to present the underlying documents to the Civil Party.[2] Mr. Lysak wanted to know whether she recognized the names Sam Yoeung and Heng Na on the list. The Civil Party confirmed this.

Sam Yoeung remained living in Chamkar Leu during the Old Regime, but got separated from the family in 1975. She relocated to Phnom Penh in 1975. She heard her aunt talk about her relationship with Khieu Samphan sometimes. The Civil Party elaborated that her aunt told her about a meeting that took place in 1972, in which Khieu Samphan came to Pou Preng Pagoda and that was attended by five hundred to six hundred people.

Initially, Sam Yoeung worked secretly starting from 1967. She did not know where she worked in Phnom Penh, because they had lost contact since then. This was around the time that the Khmer Rouge took power in Phnom Penh.

National Deputy Co-Prosecutor Seng Leang then took over the questioning. Her brother and nephew also disappeared. He asked her whether she had a sister called Noeung, to which the Civil Party said that it was herself.

They got up at 3 am. In the morning, they cleaned the rubbish at the buildings. At 10 am, they collected raisins and loaded them onto trucks, after which they would have lunch. She was not allowed to rest during her pregnancy. She was also not granted permission to rest when she did not feel her baby moving anymore when she was seven months pregnant. At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Marrying for the First Time

Presiding Judge Ya Sokhan

After the break, presiding judge Ya Sokhan issued an oral ruling on the admission into evidence of four documents. Two were the Civil Party Applications (2-TCCP-274), and the other two documents were excerpts of a Civil Party Application (2-TCCP-286).[3] The documents were admitted.

The floor was then handed to the Nuon Chea Defense Team. Liv Sovanna inquired about the background of the relationship with her first husband. She answered that her first husband lived in another village. The villages were “far away from each other”. She estimated that the distance was around the same distance as Phnom Penh and Kampong Cham. They did not know each other before their marriage. “It’s different to youths nowadays”. Their parents arranged them to get married. They met on their engagement day for the first time. She was between 15 and 16 years old at the time. It was her parents’ decision to marry her and she did not dare to oppose the decision. “We had to follow our parents’ decisions”. This took place in around 1968 or 1969. They trusted the man, which was why they married her to him.

Process

As for the Democratic Kampuchea regime, she had heard about other people getting married. She did not witness the arranged marriages herself, since she was working. Some marriages were voluntary if both spouses agreed to marry. Mr. Sovanna wanted to know whether it was correct that they could propose to each other first and then ask for permission. She denied this. “It was not like this”. The man would propose to the chief first. She only witnessed one case like this. Her cousin was forced to marry Voeun, a handicapped person. This was in 1978. This prompted Mr. Sovanna to quote her supplementary information form, in which she had talked about her cousin and asked her whether she remembered the specific year when her cousin was taken away.[4] She replied that she could not recall it well whether it was in the beginning, middle or end of 1978. He said that she had indicated in her information sheet that it was at the end of 1978. She said that this must have been “confusing”, since she also got married in 1978 and her cousin was taken away that year too.

The unit chief asked her to marry. He had indicated another man, and she had said that she would agree to marry that man. However, on the wedding day it was another man. She did not meet that person again. The unit chief was called Comrade Chhen. At her place, the chief was not called Unit Chief but Union Chief. Her chief was a man.

Moral Offenses

Civil Party (anonymous)

She never attended a big meeting. She would only attend it for a brief time. She only attended regular base meetings in full. At the big meeting that she attended briefly, she heard about moral offenses. Mr. Sovanna quoted a Youth Magazine and read out Point Six: “Don’t touch the women, because it will harm the reputation of our people. […] Related to the current marriage, there was no problem, as long as we stick to the two principles of Angkar: Both sides agree and second point, the collective agrees.”[5] She said that this was true in the beginning, but at the time of her marriage “it was an absolutist practice” and they were forced to marry. Her parents were not aware of her marriage, since they lived at a different location. “I did not have time to invite my parents and siblings to my wedding”. She believed that she got married in early 1978, since she delivered her child in late 1978.[6]

She did not know whether the other women from her wedding ceremony were widows or single, nor did she know them before or had made contact with them after. She was called to Phan the same night of her marriage. Phan came to see her, because her husband complained. She could not recall the distance. Her husband stayed in the room while she was being called. In the room that she was called to there was a table, a chair and a bed. Phan was sitting on the chair near the table. He asked why she had resisted. “And then he forced upon me.” He had a pistol and she was afraid of being killed, which was why she stopped resisting. She knew it was an offense, but “who could dare to resist him?” She said that it was the first time she told anyone about this “I have never told anyone about it. Not even my blood sibling.” She continued: “This is the first day that I spill it out. That during the regime there were cruel people. There were bad and innocent people.”

“The rape was a warning to me”. The night that she met her husband, she saw the militiamen below their room. “That’s why I decided to sleep with him”. She told him that there were soldiers on the ground. They did not talk much. “We spoke about our disagreement and I told him that I disliked him. I did not speak much, and that is my habit. I did not like talking.”

Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Liv Sovanna

Mr. Svoanna quoted her statement, in which he had said that it took her around one year until she consummated her marriage.[7] She replied that she had made a mistake in her statement about the year and that she consummated the marriage around ten or fifteen days after her wedding. He pressed on and said that she had said in her statement that it was a year later. She replied that she had told him already that it was around ten or fifteen days after her wedding. “Of course when I’m asked many questions, I am confused.” She addressed Mr. Sovanna directly: “When you reach my age, you tend to make mistakes, because of memory gaps”. She insisted that her previous statement must have been wrong and that she was certain that it was not a year after. Mr. Sovanna asked whether her statement, which she had made seven years ago and therefore closer to the date that it happened, was not correct, or maybe rather her statement today. She explained that it was not directly afterwards. “I noticed there are some mistakes in my previous statement”, she said. “I feel a bit dizzy when you ask back and forth about the event”. Mr. Sovanna explained that it was his legal duty.

He then wanted to know whether she physically resisted him. She explained that they did not argue when she told him that there were soldiers under the house. A month later he returned. “This was probably the time that we had sex”. The soldiers under her house were nearby. “It’s not my habit to talk in bed. Even with my first husband, I did not talk in bed. They were there try to listen to what we said, but I did not say anything, so they could not hear anything”. They were within the vicinity of the house. “I pretended not to see them”. She said that they were “of course” ordered by the chief to spy on them. The houses were not high from the ground, since they were only three staircases[8] from the ground. They were newly-built houses and there were no gaps in the wall. The windows were very high, so you could not see them from the ground. It was a thatch roofed house. He asked why he thought that her husband raped her. She said that her husband had tried to force himself upon her and tried to rape her on the night of the marriage, but that she resisted him. This was not the case the next time. During the second encounter, “he did not do anything, because we were afraid under monitoring”. She said: “You keep asking me back and forth, but I believe my statement is in chronological order”. Months later she had sex with her husband, and not during the first or second encounter. She agreed to sleep with him when she was “so afraid”. By late 1978, she delivered her child. “And although you are this young, I believe you cannot remember all details”, she addressed Mr. Sovanna. With this, Mr. Sovanna concluded his line of questioning and Judge Ya Sokhan concluded his line of questioning.

Consummation of the Marriage

Judge Claudia Fenz

After the break, Mr. Sovanna asked again about the first intercourse with her husband. She said that it was one or two months after the wedding. Ms. Guirauf interjected and said that the questions seemed to be repetitive. She said that she did not protest, since she was afraid. When Mr. Sovanna repeated a question about the first sexual intercourse she had, Judge Claudia Fenz intervened: “There is also a certain need of sensitivity and, if you disagree with that, to stick to the rules”.

Mr. Sovanna moved on and asked about her pregnancy. She could not remember when exactly her daughter was born. When Mr. Sovanna repeated a question yet again, Judge Fenz interrupted him. “Tired. We’re getting tired. That has nothing to do with sensitivity. These are the rules. Don’t repeat”. He asked her whether it was her free choice to live with her husband. She explained that there was pressure from her family, but that they lived “normal” since she did not talk much.

The floor was handed to international Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Doreen Chen, who asked how she knew that they would be reprimanded if they did not consummate the marriage. She replied that she knew this, and that people only addressed each other as “comrades” and not “sweetheart”, for example.

Ms. Chen wanted to know how she knew that they were monitoring them specifically and whether they were consummating their marriage, and not just monitor the security in the village. The Civil Party replied that she saw them sitting there, which made her conclude that they were monitoring them. She heard of cases when people did not consummate their marriage. She said that she felt her answers were getting repetitive.

Relatives

Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Doreen Chen

Ms. Chen wanted to know how she and her cousin could see each other often, even when not living in the same village: were they allowed to move around freely? The Civil Party replied that they had no freedom to move around, but that they worked close to each other and would accidentally see each other sometimes. When Heng Vanny was taken away, she heard from other people that she was taken away and saw a comrade wearing her cousin’s clothes during a meeting. “So I concluded my cousin was killed”. Ms. Chen quoted her supplementary information form.[9] She then inquired who had told her what happened to her niece. She said that when she was taken away from Phan, she was told that her cousin was taken away and killed. She had never met her again, nor received any news from her. It was the same Phan who “caused harm” to her. Phan disappeared later on as well.

Ms. Chen asked how Phan knew her cousin, since she was in another village. She replied that the villagers told her, because they knew that they were related. Phan did not know that they were related. Ms. Chen then wanted to know why she only told the Court today about the incident of rape. She replied that “whenever I was asked about it, I spoke out about the suffering. Previously, I never told anyone about this.” When Ms. Chen asked why she then mentioned it today, National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang objected and said that the question was repetitive. Judge Fenz explained that the first question related to why she had not told it before, but then asked why she mentioned it today. Civil Party Lawyer Hong Kim Suon referred to the Civil Party’s statement and pointed out that she had said that she agreed “to the force from my husband and other people”. Hence, this was another way in Khmer of talking about rape.

The floor was granted to the Khieu Samphan Defense Team. Mr. Kong San Onn wanted to know what her aunt’s name was. She replied that it was Saom Chorn. She did not have any other aunts, but Saom Chorn might have had aliases. He asked whether he had another aunt called Saom Chun, or whether this was an alias of her aunt. She did not know the exact location where her aunt worked in Phnom Penh. When she saw her last, her aunt looked “normal”.

National Defense Cousel Kong Sam Onn

He read an excerpt, in which she had said that his aunt was suspected of being affiliated with the Khmer Rouge – that is Khieu Samphan – and arrested, tortured and killed.[10] During 1970 and 1971, they arrested her mother. She said it was perhaps a mistake by the note taker for her statement, since it was not her aunt who was arrested. Her aunt worked in Chamkar Leu District. She used to say that in 1971 or 1972, Khieu Samphan gave a propaganda speech in a pagoda. The Civil Party also attended a meeting, in which Khieu Samphan participated, but she stood outside the temple and was far away.

She was used as a medic sometimes, but did not have any training in medicine. In the union, she was a normal member. With this, Mr. Sam Onn concluded his questioning and the opportunity was given to the Civil Party to make a statement on harm on suffering.

“I’d like to ask Khieu Samphan the following question: what is the relationship between him and my aunt, Sam Yon? And why was she taken away and killed at Tuol Sleng, since she worked with him?”

This concluded the testimony of the Civil Party.

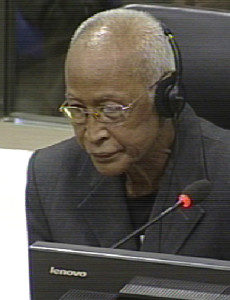

New Civil Party: Sou Sotheavy

Judge Ya Sokhan ordered to user in Civil Party 2-TCCP-224. Civil Party Sou Sotheavy was born on 8 December 1940 in Tralach Commune, Takeo Province. She said she could remember the events well. “It is like a record on the computer. My memory is still vivid”.[11]

In 1975, she had not changed her sex yet. However, she said that she was a transgender and that she did not love women.

She dressed like a woman since she was ten years old, and also in 1975. When she arrived in her native village, she took of her women clothes, but refused to cut her hair. When she was evacuated from Samlong Mountain, her hair was not cut yet. When she arrived, the people told her that Old People and New People would be married. They then cut her hair. She was considered a 17 April Person. She was relocated again. “I was asked to get married, but I refused”. When she arrived in Cheng Village from Doung Commune, the announcement was made that people would be married. She was forced to marry in October 1977. “It was the unit chief who forced me, threatened me, to marry”. She told the person that her mother was old and begged for his pardon to look after his mother. “The Khmer Rouge never compromised with us”. Every time she talks about it, she said “I feel so tense, because every time we protested or disagreed with them, we were threatened that we would be taken away to be killed”. All her family members were “gone”, she said, and that her mother was also taken away and disappeared since then. “At that time, I felt that whatever happened, I would accept it. My in-law told me that I had to agree, because if I continued to refuse, I would also be taken away to be killed. I kept on refusing to get married, because I never loved women. I loved only men. That is my nature since I was born”. She did not know where her mother was killed. “They did not tell me any reason. They simply forced me to get married”. She was relocated to a mountain, where they “kept the 17 April People and people without relatives. And I myself as a transgender woman, I was also required to live there”. She was forced to work there.

Marriage

She was not informed of her marriage prior to her wedding day. She was breaking rock at Svay Hill together with other workers. She got to know a woman who was supposed to get married the same day. Both of them were orphans and 17 April People and said that they should consent. “I told her to have a scarf on her head while I had a scarf on my neck”. By 6 pm, “everybody came, including chief of the unit, chief of the commune, and villages. And that’s when the ceremony started”. The respective female and male members of the unit chiefs came to tell them. They were gathered at Svay Kram Hill. They could do “nothing else besides breaking rocks” at the hill. The unit chief called them at around 3 pm. In the afternoon, they were “required to line up” and they were wondering what happened. They thought that they were for a study session, and only when they were lined up were they told that they were getting married.

“I’ll remember until I die, because that was the point that caused me the most pain. They made the announcement that the pop of cam was not that great […]. And for that reason Angkar required us to get married to increase the population.” There was a rumor about marriages in February, and in August the marriage took place. There were 107 couples together, 80 of them who were 17 April People. She was in the seventh couple. “I remember that vividly.” The same day, she decided to talk to a woman. They were not told about the marriage before. “We were in a line, and the women were in a separate line. Then they played a game similar to hide and seek. They switched off the light and we had to feel a woman’s body”. She had suspected this, which was why she had told the woman to put a scarf on her head and she would put a scarf around her waist so they could recognize each other. “I got hold of her hand and she got hold of mine”. They had to make a resolution. There were two base people and four 17 April People before her. They had to vow to “produce children” for Angkar. “Then they clapped their hands”. “We could not refuse. That was the time that we had to follow them”. Some couples had been taken away previously under the pretext of taking them for a study session. As for her wife, she said: “That woman understood me; that I was in that fashion, and that’s why she agreed to our arrangement”. None of the 107 couples refused. “However we could see that some people shed their tears quietly.” Some of the men also wept quietly. “I did not know about their personal feelings, but that’s what I observed.” She did not have any feelings for that woman.

Wedding Ceremony

The wedding ceremony was not organized according to Khmer tradition. Instead, it was held “according to Angkar’s plan. We were forced. There was nothing played over the loudspeaker”. Only a small loudspeaker was used to instruct the couples. “They spoke about producing children for Angkar, having respect for Angkar, […] so the marriage was not organized according to the traditions”. She did not know who presided over the wedding ceremony, and only knew that he was in a senior position. Some of the clothes were dirty. “The scarf that I wore was old and unwashed. So you can imagine that we were forced, that we were compelled to marry”. Her bride Yang Rotha was from a nearby commune and both of them belonged to the same commune (Doung Commune). She did not know where the bride originally came from. The female unit was based in another location, while the male unit was based on the mountain. They met when the male unit was allowed to visit the village once every ten days. She did not know how old this woman was. She said that this woman was older than 50 now. “She was around twenty-something, while I was thirty-something in 1977”. Those who did not have houses returned to their respective unit. Ms. Sotheavy returned to her relatives’ house, which was one meter off the ground. “When we went onto the house, at around 10 or 11 o’clock at night, when I was chitchatting with my elder in-laws and my wife, we looked under the house, and we saw movements of shadows, although we did not know who they were.” Thus, they knew that “they came to spy on us.” After they got married “this time, they wanted to make sure whether we consummated the marriage or not.”

International Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

Ms. Guiraud asked whether they consummated the marriage the first night, which Ms. Sotheavy denied. “It continued for several weeks that we were taken for study sessions”. She told them that they had consummated their marriage, but they did not believe them. They told her that she was transgender and that she could therefore not consummate the marriage.

“They warned that if we did not consummate and if they found out, we would be smashed. But I told them that we did. We were threatened repeatedly until we decided to consummate the marriage. One day, the village chief who liked me, gave me some wine […] We got drunk and then I said that if we do not consummate the marriage today, one day they would find out and we would be killed, and that we run out of lies and we said that we should do anything in order to survive. And then, under the effect of the alcohol, my mood changed and that’s how I consummated the marriage”.

She explained: “Throughout my life, that was the only time that I had sexual intercourse. So far, that was the only time. I am seventy years something old and that was the only time that I had sexual intercourse.” After the marriage and after she consummated the marriage for one time, they were separated. “They knew that we slept with one another” and sent her away. Every ten days, they were allowed to meet each other, “but I did not have any sex with her”. She did not even notice that her wife became pregnant. “She could see through my poor physical condition that my kneecaps were as weak as my head.” They failed to find any relatives after the Khmer Rouge regime. “Half of my body should have been paralyzed from hyper tension”. Crying, she said that she wanted to express her pain to the Chamber.

Daughter

She was not aware that her wife was pregnant until her wife delivered a daughter. “And the female baby was beautiful”. She wanted to go home to see the face of her daughter, but she could not walk.

Some couples got separated. “They were taken away for study sessions and they disappeared. They never returned to the village”. Only around ten percent of those who married on the same day as her survived. “Occasionally, I met one of them”. “People had the right to get divorced only in 1979.”

Since the baby was born until nowadays, “I have never received any news about her.” As for her wife, she did not know whether she is still alive today, nor where she would live if she was still alive today. “I also tried to search for my daughter and my wife, but I could not find them, since 1980 until now, I tried to search for them, but I could not find them, although I am a transgender, I have sympathetic feelings toward them”.

Turning to her last question, Ms. Guiraud asked what she felt when thinking about these events today. “Although I was a transgender, I had a child like other people, and it was tragic that we got separated from each other. It was painful for me. Although I did not love woman, I still feel sympathy toward my child. When we were reeducated together, I felt frightened. I tried hard to find them, but I could not.” Since then, her health has not been good.

Follow-up Questions

Civil Party Sou Sotheavy

The floor was granted to the Co-Prosecutors. Nicholas Koumjian thanked the Civil Party for coming to the court and asked about the age range of the over one hundred couples that participated in the ceremony. She replied that the age was similar. “Many of them were young, but not too young.” She estimated that the men were between 20 and 30. The ceremony took place when the sun was setting. They were asked to stand up in line. She confirmed that they were asked to touch each other to find each other after turning off the light. She felt “satisfied”, because she was able to find her partner. Other couples wept, including men and women. “They kept weeping.” Mr. Koumjian inquired whether it was possible to change the arrangement once the light went on again. “We even did not dare to cough. We did not dare to talk. Because if we talked, we would disappear”, was her answer.

Their clothes were dirty. “I saw the commune chief and the deputy commune chief”. As for Zone leaders, she said that she saw Ta Mok, Ta Saom and Ta Chan. She never saw other leader, such as Pol Pot. She saw Ta Mok at the “Historic Dam” that went from Angkor Borey to Trok Deat. When she was in Tralach Commune, she also witnessed the marriage of handicapped people from the military, who got married to the Base People. They had tables and chairs, which was different to the wedding of the 17 April People. Because she was short, she stood in the front. Handicapped persons were married to those women who were considered loyal to the Party. “They were chiefs of the cooperatives, they were medics at the cooperatives”. She saw the disabled soldiers coming to the marriage. “It was not forced. The women were asked to marry those soldiers, and no one dared to refuse”. However, the number of couples was smaller, and she did not hear threats. When she was in her homeland, there were cases of forced marriage, but transgender people would refuse. “Even if they had to commit suicide. They would commit suicide by drinking a poisonous drink”. When her mother died, she felt “lonely in this world”. “All my friends who sang together with me in the bar disappeared”. They were shot at, and only Sina and she survived. Later on, she got separated from her. “As for other friends of mine, [they] died at the stadium. They were shot dead there, and I never met any one of them again.”

None of her family members survived. “All of them were killed. I witnessed two of them with my own eyes who were tied up. They were sent away to study”. Only she survived.

After taking a short pause until Ms. Sotheavy, who was crying, could answer again, Mr. Koumjian asked whether she was told who Angkar was. She replied that she could not clearly identify who Angkar was, “because everyone who was in authority was called Angkar”. She did not know much about the Communist Party, she said.

Mr. Koumjian inquired what “it was like” or what they had seen that made people feel like they had no choice but to accept the marriage and were unable to refuse. “All of them were in a tense situation […]. But they did not dare to speak, because their relatives and parents would educate them to grow the so-called KO-r tree, or dumb tree.” She explained that this meant to simply follow orders. “They would accuse us of being members of CIA or KTB”. Hence, they did not dare to protest or speak out. They had no concrete evidence to accuse them. “If they wished for a person to die, they simply said that the person was a KTB agent.” “If we wanted to survive, we had to be quiet”.

On this note, the President adjourned the hearing for today. It will continue tomorrow morning at 9 am with Sou Sotheavy’s testimony and reserve Civil Party 2-TCCP-264.

[1] E3/6011a.

[2] E3/10604, at 8467; E3/10450.

[3] E340.

[4] E3/6011a, at 01003356 (KH), 01137890 (EN), 01030293 (FR).

[5] E3/765, at 00515493 (KH), 00539399 (EN), 00540025 (FR).

[6] E3/011a, at 01003356 (KH), 01137890 (EN), 01030293 (FR).

[7] E3/6011, at 00496721 (KH), no translation available.

[8] This was probably a translation error and meant three steps.

[9] E3/6011a, at 01137890 (EN), 01003356 (KH), 01030293 (FR).

[10] E3/6011, at 01003355 (KH), 01137889 (EN), 01030292 (FR).

[11] At 00845987 (FR), 00279712 (EN), 00279728 (KH).

Featured Image: Sou Sotheavy (ECCC: Flickr).