Handicapped Soldiers Were Married As They Could Not Fight

Today, August 30, 2016, Civil Party Seng Soeun concluded his testimony in front of the Chamber. He reported about the arrest and execution of a cadre who had “made up confessions”, as well as the execution of the ten ethnic Vietnamese and Chinese – a matter that he had testified to yesterday as well – and the treatment of former Lon Nol soldiers.

Next, Civil Party Chea Dieb took her stance. She had served in a mobile unit affiliated to the military and talked about arranged marriages. She said that handicapped soldiers were married to women from other units, since they could not serve at the battlefield anymore.

Arrests of a Cadre and Authority of the Civil Party

Civil Party Seng Soeun continued his testimony under questioning of the Nuon Chea Defense Team. He stayed in Kratie for around a month. Defense Counsel Victor Koppe wanted to know whether he was ever involved in arresting people himself, which Mr. Soeun denied. “I was in charge of record keeping for the district.” Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he knew a person called Cheam who was involved in the events on Koh Kor. He replied that he could not recall the names of the people who were detained there. He remembered that there was a district committee who was sent there and asked him for a cigarette, but he did not know his name. To refresh his memory, Mr. Koppe read an excerpt of his interview, in which he said that “A-Cheam” was responsible for Koh Kor, but that he arrested him later, because Cheam had arrested too many people.[1] Mr. Soeun said that he could recall him now. He was instructed by the district committee. He pointed a gun at Cheam while the district committee arrested him. The district committee said that he made up confessions.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he was in a position to release anyone. He replied that he did not release anyone and that he was only involved in this one arrest. This prompted Mr. Koppe to read out his DC-Cam statement. “I managed to release some families”.[2] He confirmed this, but said that he did not release people who had been detained. Instead, he wrote a letter not to arrest them.

Mr. Koppe said that he was in a position to release people and that he was involved in the arrest of a relatively high-ranking cadre. He asked whether he “was sure” that he was never instructed to investigate the matter of rice being hid for Vietnamese soldiers. The Civil Party denied this.

Mr. Koppe read another excerpt in which he had talked about Ta Ha Noi. He recounted that Ya told him that a cadre came and that he instructed him to “take him”. He considered him as his elder brother. He did not know what happened to him, but was told that this was “the end of his life”. He denied that he was ordered to arrest and execute him.

International Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether he knew who Kang Chap was. He replied that the name sounded familiar, but that he did not have any contact with him. Mr. Koppe read an excerpt of his DC-Cam statement, in which he had said that he was a Vietnamese spy and trained in North Vietnam.[3] Mr. Soeun said that he could recall that Kang Chap was transferred. He denied having said that he was a spy. He did not know about Ta Mok’s biography. “I saw him only when he was already a man”. He only knew that he was a leader of the Southwest Zone. Mr. Koppe did not believe this: “Really, Mr. Civil Party?” He then read an excerpt, in which he had described Ta Mok.[4] Mr. Soeun answered that he knew him at the time that he was injured. Ta Mok instructed the medical staff to take care of the patients. Mr. Koppe also sought to retrieve more information relating to an incident with a watch, an incident that he himself classified as rather minor. However, he argued: “It goes to your credibility”.

Mr. Koppe said that he had told the researchers that Ta Mok was a kind person and that he gave him his watch.[5] He confirmed that he received the watch from him in person.

Mr. Koppe asked whether he knew Ruos Nhim and Sao Phim. He heard about the announcements of their names before.

Mr. Koppe then inquired about the Standing Committee Members and wanted to know how he knew that Ruos Nhim was part of it. [6] He did not give a conclusive answer.

Mr. Koppe then wanted to know “what was the problem in terms of the border between DK and the Vietnamese?” Mr. Soeun replied that he had no knowledge in cartography. Asked whether he was involved in planting mines and border posts with the flag of Democratic Kampuchea, he said that he was “aware of it”, but that he did not participate. Mr. Koppe then read an excerpt of his DC-Cam statement, in which he had talked about the planting of mines. [7] He answered that he was not the one who participated, but other people from his unit. As for Vietnamese “encroaching on our territory”, he recounted that they came every day, but only in small groups. He heard about Vietnamese entering the country after 1975, but at that time he was already handicapped, he said.

Executions at Koh Kor

Judge Claudia Fenz

Turning to his next topic, Mr. Koppe inquired who “physically ordered the execution” of the ten people at Koh Kor. He replied that the chief of the prison conducted the execution. The order came from the upper level to Brother Phon. When Mr. Koppe asked who ordered the execution again, Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak objected and said that the questioning was repetitive. Mr. Koppe said that he was asking about a person who verbally ordered these people to execute the prisoners. Judge Fenz intervened and asked the Civil Party whether he had heard anyone command the people to execute the prisoners at the scene. The Civil Party said that he did not hear anyone give the order on the spot. The commune chief ordered them to gather Vietnamese and Chinese people and send them to Koh Kor. The chief of Koh Kor reported to the district when he received these prisoners and later kill them. Sao Phon was the district committee and ordered the Koh Kor Prison Chief to execute those people. Commune people would transport these people. Mr. Koppe read an excerpt of the DC-Cam interview, in which he had talked about the Koh Kor Prison.[8] Mr. Lysak interjected when Mr. Koppe asked who held the authority at Koh Kor and said that he was now inquiring something different than what the excerpt had referred to.

Mr. Koppe wanted to know whether A-Cheam was responsible or Sao Phon for the Koh Kor Prison. He replied that Sao Phon had given an order to execute those people and that the executioners were the subordinates or Cheam, who was the prison chief of Koh Kor.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Cheam was not yet arrested when the executions took place.[9] He was arrested perhaps ten days after. His arrest was not due to the arrests of the Vietnamese and the Chinese people. Mr. Koppe wanted to know how he knew that they were ethnic Vietnamese or Chinese. He answered that he did not say that they were brought in, because they were of particular ethnic groups. They “spoke Khmer clearly” and he did not have time to talk to them. He denied having said that they were Chinese or Vietnamese expatriates. He did not see whether they were ethnic Vietnamese or not.

Mr. Koppe, before posing his next question, said that The Civil Party Lawyers and Co-Prosecution “have neglected advising you that you have a right not to incriminate yourself” and then asked whether Mr. Soeun was involved in the execution of those ten people himself.

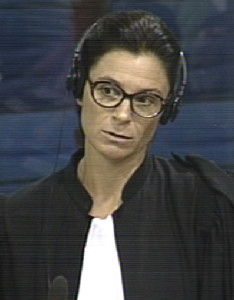

International Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud interjected and pointed out that Mr. Koppe did not know what the Civil Party Lawyers had been discussing with Mr. Soeun. “He should take care of his client and we will take care of our clients”

Mr. Koppe directed his astonishment, he said, to the Chamber and asked why this particular Civil Party had no duty counsel. He then repeated his question. Mr. Lysak interjected and said that “he should stop playing games in the courtroom by trying to intimidate”.

The Civil Party then explained that he stood next to the execution. Mr. Koppe addressed the Civil Party: “you were the one that arrested the person who was responsible” for this execution and that he would not be someone who was an “innocent bystander”. Judge Claudia Fenz directed the counsel not to use the term “innocent bystander”, since this was a subjective term. Mr. Koppe was visibly frustrated: “Please give me a break, Judge Fenz”.

Former Lon Nol Soldiers

Mr. Koppe then inquired about a policy to kill Khmer Republic soldiers. He said he could not recall it well. It was after 1975. He said they called it cleansing. He attended a military session where he was based. “And after that I became a handicapped person”. This took place at a school. This was called a political study session. Mr. Koppe said that they had evidence that in the Southwest there was a policy not to touch ranked soldiers and asked whether this was something he had heard. Judge Fenz instructed him to give references. Mr. Koppe replied “You were there, you heard it”. He then asked the Civil Party whether he had heard that soldiers below the ranks of colonels should not be touched, which Mr. Soeun denied. He could not recall well where he heard Phan talk about the former Lon Nol officials. The lecture took place in his battalion. He could not recall where the battalion headquarter was based, but it was based in Koh Andet District close to the Vietnamese border.

Mr. Koppe moved on and asked about his statement that “New People had to be smashed”.[10] He replied that he did not say this.

Mr. Koppe asked why people of Chinese origin were supposed to be executed. He replied that he only heard about the killing at this one particular event. “I could not elaborate any further regarding the CPK plan or policy”. Mr. Koppe said that he had said that “there was a plan to smash ethnic Vietnamese and ethnic Chinese” and wanted to know why there was such a plan.[11] He answered that he did not know about this.

The Defense Counsel then turned to a slogan that the Civil Party had mentioned “no other race than the Khmer”. He said that he had not read this. He said that he did not want to know anything about the regime. “It is already fortunate for me to survive”. Mr. Koppe said that he was not sure that this was correct, but concluded his questioning.

Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak

The floor was granted to the Khieu Samphan Defense Team. Anta Guissé wanted to know whether he also arranged marriages for people in the communes and villages. He replied that he received his assignment to marry people from the mobile units. He had to match them. Ms. Guissé quoted yesterday’s testimony, in which he had said that the commune chiefs had to arrange the marriages.[12] A district chief had testified that the district chiefs sent proposals in Baray.[13] He explained that the authority rested with each commune, who had to select people to get married. Twenty or thirty couples had to be selected on one day. The respective mobile units would select the people and Phon would give the list to Mr. Soeun, who matched them. The men had to be three to five years older and their biographies had to be matched. Phon made the announcement about the couples and said that if any of them disliked one another, they could leave. “He gave them such right”. They were called by their respective unit chiefs to attend the wedding ceremony.

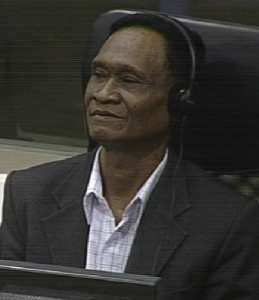

Civil Party Seng Soeun

Ms. Guissé then read an excerpt that had been presented to the Civil Party already by the Prosecution and asked whether he had any example of a village or commune chief who “altered the truth” by wrongly accusing people of being an enemy.[14] He denied this. Ms. Guissé asked on what basis he had said it to DC-Cam. Mr. Soeun answered that the word “happened throughout the country” and that “everybody spoke about it”. He could not remember clearly who had told him this. He was instructed to arrest the prison chief, because “he falsified the confessions”. This person had “made up the report”. He could not recall having made a statement regarding lower ranking cadres who “ruined the party lines” and having said that lower cadres should be tried.[15] He said that he had no greater knowledge about this. He heard about it starting from April 1975. She asked whether he heard people criticize the way the party policy was implemented. He said that “I did not say that seriously, it was simply an informal chatting amongst us. It was simply a joke”. Ms. Guissé replied “that’s kind of a funny joke, but with whom would you chitchat that way?” He could not recall. “We talked about this under the influence of alcohol”.

Civil Party Statement

I do not have much to say, but I would like to request to the chamber that my life suffered a lot from 1970 to now. I served the nation and I sacrificed for the nation. I became a handicapped soldier. My relatives were killed. And those suffering were beyond words to describe. I myself, as a handicapped person suffered a lot. I do not know the words that I could use to describe the situation [and] about the experience I encountered in my life.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

New Civil Party: Chea Dieb

After the break, Presiding Judge Ya Sokhan ordered to usher in 2-TCCP-286.

Civil Party Chea Dieb was born on 7 April 1954 in Pramat Dei, Chamkar Leu District, Kampong Cham Province.

Civil Party Lawyer Sin Soworn

The floor was given to Civil Party Lawyer Sin Soworn. Before 1975, she lived in her birth village with her family members. In 1974 she left her family to join the army. She was in the mobile unit of the military. She joined the army through Comrade Han and Hien, who were the committee members of Chamkar Leu District. At the time, her unit was called the “transport mobile unit” and they were responsible for transporting wounded soldiers from the battlefield. Sometimes they were deployed to fight.

Her battalion consisted of 300 people and was divided into smaller units. They were based to the north of Phnom Srok Phnom Srei and along the riverbank. She transported ammunition, wounded soldiers, and dead soldiers. She also participated in fighting. The combatants entered Phnom Penh on 17 April 1975 and she entered later. She first stayed in the north of Wat Phnom. Later, they were moved to Calmette Hospital. Her big group was in charge of transporting “the things from people’s houses”. She helped organizing the possessions after they were collected.

Arranged Marriages

She met Khieu Samphan at Ounalom Pagoda and later at the stadium. This was on the day that Hu Nim was tried. At Ounalom Pagoda, Khieu Samphan said that female people needed to work and that all male and female youths should be arranged to be married. She said that he did not say whether the marriage was based on love. “He said that they should get married to produce children”. With these children, they could defend their territory better. After this announcement, her forces were announced to get married. She was married in 1975. Her immediate supervisor Phan arranged her marriage. When her superior told her she refused, because she was “still young.” She could refuse twice. On the third occasion, he instructed her to go to Orussey Market, where she was advised that she was a child of Angkar. They were married at Dangkor Market. The ceremony took place in the afternoon. She was three days prior to the ceremony that she would get married. She did not receive permission to visit her parents.

She and her husband knew each other only on the day that they were matched. There were twelve couples attending the ceremony. She knew Sae, Ha, Sao, Vy and Leang. The other women came from different locations, so she did not know them.

The women were also female combatants. The men were handicapped combatants. “Some lost legs, some lost hands, some were one-eye blind”. Her spouse could not walk properly and had a problem with one of his legs. During the marriage ceremony, they paired them up. “We knew each other only after the announcement of our names”. Each of the couples had to make their commitment to their marriage. They were instructed to “love one another” and to “strive to work hard to build the country”. She did not know who made the presentations.

After the marriage they were divided into groups. There were three couples in her group. They rested at Toul Tom Poung Market. They stayed in three different rooms. She could hear the footsteps. She heard militiamen going up the stairs to “listen to them”. When the militiamen started being quiet, the couple did not dare making any noise either.

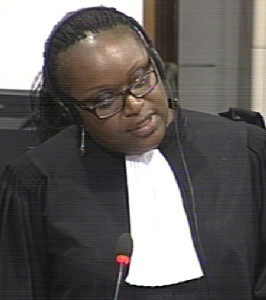

Civil Party Chea Dieb

She did not consummate the marriage the first night, “because I was afraid of both my husband and the militiamen”. They stayed at the house for three days before going back to work. They were allowed to meet every ten to fifteen days, which was when she consummated the marriage. This was her husband’s choice. “If militia found out that a couple did not agree [to consummate their marriage] they would be put for re-education”. The quickest was a week, but sometimes they met every one or two months. When Ms. Soworn asked about her being forced to marry, Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn interjected and said that she Civil Party had not said that she was forced to marry. Ms. Soworn explained that she had used the term “forced marriage”, because she had first refused but her refusal was ignored. “I did not like my husband, but I did not know what to do”. She had nowhere to go either. “I had to follow along, since I could not refuse it. I had no other choice”. She was not happy with Angkar having organized marriage for her. “I wept almost every day. I felt pain, but I could not do anything”. The wedding took less than one hour. If comparing the marriage to traditions before and after, she said that “it was absolutely different”. At present, only one couple would be married at the same time, and they would be surrounded by their relatives. “If you compare it to the Khmer Rouge, it is as if you compare to the earth to the sky”. “I feel the pain in my chest”, she said. “I lost everything. […] I still feel the pain now”. She lost four siblings, her nieces and nephews (around 15), her uncles and great-uncles (around 10). “And for that reason, I suffered too much”. The loss of family members and relatives gave her “much pain”. “And I only depend on this chamber to give me the solution to these losses.” She would physically feel the pain. “I can never forget the loss of my siblings, parents, family members […]”. She said she felt the greatest loss for her younger brother, who was accused of moral offense. He was hung onto a tree upside down and died. She had to take care of her younger siblings. After the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime, she “found it very difficult to survive”, since they neither had equipment to plow the rice fields nor had money. She became unhealthy and emaciated. “I am never happy”, she said.

With this, Ms. Soworn concluded her line of questioning. Senior Assistant Prosecutor asked about the youth league. She answered that she was part of the female combatant unit. She first joined Battalion 401, but she did not know which regiment it belonged to. She could not remember what happened to Oudong area. She never met high-ranking cadres at the battlefield. Mr. de Wilde inquired about the Ministry of Commerce. She said that she was in charge of “collecting everything”.

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

Ms. Guissé interjected and sought clarification for the Ministry of Commerce or Commerce group. When Mr. de Wilde rephrased his question, Ms. Guissé objected, saying that the question was leainh. She replied that her unit consisted of 300 personnel. Her unit was moved to join with the Commerce. Comrade Puth alias Koy Thuon was in charge of this. Thus, she was part of the Ministry of Commerce. He did not know what happened to him.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Role of Khieu Samphan

After the break, Mr. de Wilde wanted to know whether she had ever heard of S-21, which she denied. There was a meeting at the stadium, but she did not know when. She saw Khieu Samphan there and many people attended the meeting. She also met him at Wat Ounalom. They were told that people should get married, but not the younger ones. They were between 19 and 25 or older. Mr. de Wilde inquired about disciplinary measures that had to be observed and wanted to know whether Khieu Samphan spoke about this. Ms. Dieb replied that he said that people should strive to work hard for the party and not disregard principles. “During the whole regime the discipline was very strict, and we were not allowed to engage in any moral affairs”. With this, she meant that even amongst the soldiers and people who worked at the Ministry of Commerce, they had to “respect their titles”, such as “Comrade” and “Uncle”. “If a man and a woman fell in love with each other without permission, they would be separated”. If it was observed that “they behaved” they might be married to each other after a while. This marriage ceremony would take place at night time and only one couple would be married. She considered herself “young” when she was 19 years old. She did not understand when he asked about the “Revolutionary Family”. She confirmed that Khieu Samphan spoke about the necessity to detach themselves from their parents and that they should focus on their work. The same message was submitted in study sessions: that they were supervised and that Angkar was their parents.

Mr. de Wilde read an excerpt of a the 1974 Conception of the Revolutionary World and the Matter of Funding a Family, in which it was stated that the assignment by Angkar must “at all costs” be respected.[16] She said that they had to respect Angkar’s decision.

Mr. de Wilde wanted to know how much time elapsed between her refusal and the time that she went to Orussey market, where she had to accept the proposal. She replied that there were a few days between each proposal.

Mr. de Wilde then wanted to know whether “it was obvious” to her that she could not refuse again, which she confirmed. She said that she had to “abide by Angkar’s instruction”. The first time she refused she was accused of having a fiancé and the second time they said that she had a secret boyfriend. They told her that Angkar had the eyes of a pineapple and that they could investigate. Two or three couples were “allowed to make their commitment” at a time and they represented the rest of the couples.[17]

Marriage Policy

She only heard about the word treason, and about the transfer of cadres. The leaders said that they should “love each other” and “produce as many children as possible”.

Mr. de Wilde then inquired whether her husband shared her fears to get married. She replied that she did not ask him. She knew that there was one couple that did not get along well, but they kept silent, because they were monitored. A while later, “the wife reported to Angkar”, and the husband was re-educated. “And the man said he did not love the woman, he loved only men”. It was said that the husband’s “manhood did not work”. “Angkar called in a medic to test his manhood”. After several sessions of re-education, the man agreed to stay with her. The wife got pregnant, but the wife died. The child was given to the chief of the unit. The chief of the transportation unit was female.

Mr. de Wilde asked why she consummated the marriage.[18] She explained that she could “not anticipate what would happen if I kept on refusing”. She did not become pregnant during the regime. Mr. de Wilde asked whether it was not “strange” that they were required to bear many children for Angkar, but at the same time were only rarely allowed to see each other. Only during her marriage ceremony were the couples “mostly young”. She recounted that Pol Pot came to the sewing unit.[19] He asked her whether they could survive on one bread a day, which she had denied. “And then he ordered to give us two breads a day”. They were not told that they were “the elite”, and only told that they had to work collectively.

The husbands were transferred to a stream. Some of the elder Chinese men had “long moustaches” and they told her that they worked in a factory prior to the Khmer Rouge regime. They were kept there. They said that she was connected to the leadership.

When she was sent to Wat Sleng, the chief of Wat Sleng was arrested.[20] Their forces were separated into different villages and members of their unit kept disappearing. They escaped to another pagoda that she had heard was under the supervision of Khieu Samphan. She never saw him there and only saw his subordinates. Mr. de Wilde asked why people said that Khieu Samphan supervised that place personally. She said that “people said it” but that she never met him. “At that place, no one dared to enter the compound, even the authority form the district”. The chief of the pagoda had an amputated arm.

She met Pol Pot only one time. “When he reached my place, he came in to ask me, and then he continued his walking”. She saw him on a documentary movie when he went to North Korea, but only met him once.

As for Khieu Samphan, she said that she was familiar with his face. “When I saw him, I knew it was Khieu Samphan”.

The President adjourned the hearing. It will continue tomorrow, August 31, 2016, at 9 am with the testimony of Ms. Chea Dieb.

[1] E3/5643, at 00753898 (EN), 00059404 (KH), 00756648 (FR).

[2] at 00753855 (EN), 00059350 (KH), 00796598 (FR).

[3] At 00753883 (EN), 00059386 (KH), 00796632 (FR).

[4] 00753 9393-94 (KH) 38 (FR).

[5] Ibid.

[6] At 00753820 (EN).

[7] At 00753891 (EN), 00059396 (KH), 00756641 (FR).

[8] At 00753898 (EN), 0059404 (KH), 00756648 (FR).

[9] At 00753898 (EN), 00059404 (KH), 00756648 (FR).

[10] E3/409, at answer 44.

[11] At 00059350 (KH), 00796598 (FR).

[12] At 11:15.

[13] August 22, 2016, at 15:16:42.

[14] At 00756607 (FR), 00753864 (EN), 00059360 (KH).

[15] E3/5643, at 00756650 (FR), 00753899 (EN), 00059406 (KH).

[16] E3/775, February 1974. 00401 01 00417942-43 (EN).

[17] E3/5010, at 01212920 (FR), 01003331 (KH), 01312791 (EN)

[18] E3/5010, at 01003331 (FR), 01312791 (EN), 01212920 (FR).

[19] E3/5010, at 01030100 (FR) 01003331 (KH), 01137888 (EN).

[20] E3/5011, at 01001010 (FR), 01137888 (EN), 01003331 (KH).

Featured Image: Civil Party Chea Dieb (ECCC: Flickr).