“Your Conclusion is Contradicted by Your Research”, Co-Prosecutor Challenges Expert

Today, expert witness Pen LeVine continued her testimony under questioning of the Khieu Samphan Defense Team, the Bench, and the Co-Prosecution. She gave information regarding the metaphysical meaning of marriage and the loss of protection under Democratic Kampuchea, explained why she preferred the term conscripted marriage and rejected the term forced marriage, and said that no policy of forced marriage existed. She rejected the statement put forward by the Co-Prosecutor that some marriages under the Khmer Rouge were coerced and conducted against the free will of the people.

Meaning of Angkar

Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

At the beginning of the first session, Ms. LeVine wanted to clarify her status: she had been noted as Mrs. Levine and not Ms. LeVine, and asked this to be corrected. The floor was granted to the Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé. Counsel asked how many people and what percentage of her sample told her that they were forced to marry. Ms. LeVine said that the word forced was never used in her entire sample. It was not until the word forced became an agenda item at the ECCC that people began to feel as if they were ashamed to tell their children as to where and how they were married. They did not change their understanding of their weddings being authentic, but more concerned of how media would represent their wedding. The shame factor became, she said, an artefact of the representation of their marriage in the media. She had perceived this shift in around 2004. Since she followed some of them for several years, she could see the shift in their perception. The longer she was immersed in the interviews and travels with her respondents, the way they talked about Angkar changed. This also changed how they themselves perceived the arrangement of their wedding. For example, Angkar was introduced as an organization, but the meaning shifted, and became more a metaphysical meaning of their experiences. Ms. Guissé then inquired whether the definition of Angkar emerge in the interviews she conducted.[1] Ms. LeVine said that her question had been “what is Angkar” and not “who is Angkar” after she had conducted interviews for five years. Twenty-two percent of her respondents considered Angkar to be a leader, but 48 percent gave a metaphysical understanding. To understand this, she conducted literature review about transformational spirits and the significance of a spirit in a Buddhist-based culture, how these protect people, transform, and destroy. In the interviews, it often appeared that the respondents perceived that “Angkar could appear and destroy”.

She gave the example of the first couple she interviewed and that she had asked them what they were talking about when they walked back to their parents’ place for five hours. They told her that they did not talk, “because Angkar could hear us”. Asked what they were thinking, they had replied to her that they did not think anything “because Angkar could hear what we were thinking.” This led her to investigate this issue more, but “a lot more research has to be done”. She spoke to several researchers about the term Angkar. “No one knew where Angkar was. Where was Angkar? What did Angkar look like? At the time of so much chaos, of so much upheaval […], of so much fear, it is really understandable that […] a particular kind of anxiety around this Angkar that had a particular force in and over their life”. She had received notification that investigating this in depth in her research for her PhD by looking at official documents would be outside the scope of her intended research.

Lack of a Policy

Ms. Guissé quoted Nakagawa, who had said that she thought there was a policy to arrange collective marriages, but that she did not have sufficient evidence for establishing a policy of forced marriages. She wanted to know whether Ms. LeVine came to the same conclusion. She had noticed that there were more purges being done where no weddings were done. “I think there was a relationship between the places in which there were purges and the ways in which weddings were formulated in a more sequenced way”. The way in which the marriages were conducted seemed to be dependent on leaders. There was a period of time following the wedding during which they were allowed to spend time together. Weddings were part of a plan of the regime, she said, but it varied drastically throughout time and space. In the beginning of the regime, she alleged, there was no policy, but it seemed to her – she stressed that she was hypothesizing this – that a policy was being developed. There was an informal songline that fed the beginnings of a policy.

Judge Claudia Fenz

Judge Claudia Fenz asked whether the policy she elaborated on referred to forced marriages, arranged marriages, or other marriages. She replied that it referred to weddings in general. She said that there was a general understanding that “weddings were going to happen”, but that in the early stages people had access to traditional marriages. In 1977, weddings seemed to have appeared to be more existent. After areas were purged and people were moved around to different locations, weddings started to come into these purged areas. Some rituals were re-introduced at that time. By 1978, a policy “organically happened”. However, she did not have any evidence of a written policy. “The policy was an organic one that everyone seemed to know about by 1978”.

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian interjected and said that the witness should answer the questions, since they did not object based on the questions asked. He pointed out that the question was about the 12 Moral Principle, Commandment 6. Defense Counsel replied that he would have sufficient time to ask about this later.

Ms. Guissé provided a document and asked about translators.[2] Ms. LeVine explained that when creating a movie for the Shoah Foundation, she released that translation was crucial. She said that DC-Cam staff had interviewed a person and that a DC-Cam staff member had translated the interview. She hired a second translator and noticed that there were things that were changed and those that were omitted. She highlighted those discrepancies. She said this may have been an oversight by the person who translated the transcript originally, but that this part was extremely important. She said that the term conscripted marriage was used legally in the 18th century. Its Latin origin meant “write down together”. Nine countries in the world conscripted women, she said.

There was a relationship between how Angkar was used in weddings and how the people understood loyalty and service. Ms. Guissé asked whether people spoke about their families and Angkar as targets of loyalty with regards to their marriages. With this, Ms. Guissé concluded her line of questioning.

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian requested an extra session for both sides.

Judge Claudia Fenz then took the word and turned to a few procedural issues. They admitted the questionnaire that had been raised yesterday into evidence. She clarified whether the handwritten confidentiality agreement that was before the chamber was indeed the confidentiality agreement that was used by the respondents, which the expert confirmed. They had verbally agreed, since signing the document could have had consequences for the respondents.

Judge Fenz asked her about the findings in her book for the public to understand the contents. She said that the questionnaire did not deal with forced marriage specifically. She wanted to know whether she understood it correctly that the purpose of the questionnaire was not to understand whether or to what extent forced marriage happened in Cambodia. She confirmed this. The purpose was to understand the content and structure of weddings in Cambodia to assist a better understanding of this phenomenon.

Forced Marriage, Conscripted Marriage

Judge Fenz wanted to know what the difference was between forced marriage and a conscripted marriage. Ms. LeVine answered that it was important that she only represented the experiences and responses of the respondents. “No one in my studies told me that they were forced”. Thus, it was not part of her sample. Many people referred to their wedding as if they were providing a service to the future of their country. Thus, she started to research whether historically there were countries that conscripted people for service.

Asked about the difference between conscripted marriage and forced marriage, she said that she would “self-disclose for a moment”. Ms. LeVine explained that she had been the generation in which the Vietnam War was debated in the US. Her friends were called up for the draft, and some refused to go and went to prison. She said it was difficult for her to hold the geopolitical places in the world in which conscription was not a crime.

There were people in her sample who were conscientious objectors to marry those who they were assigned to marry. “Some of them did labor that was forced”, and one of them was imprisoned for objecting. This was a consequence of the denial. She said that she came to use this term by the loyalty to Angkar that people felt. She tried to find a term that best fit how she could describe the functions the weddings held under Democratic Kampuchea. The function it held was to service Angkar. She did not have a definition of forced marriage, since it did not come up in her sample.

Before the break, Judge Fenz asked what findings the expert could make on the existence of a policy regarding forced marriage. She gave the expert time to think about this question over the break.

At this point, Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn adjourned the hearing for a break.

Definition Forced Marriage

Before the expert answered the question, Judge Fenz gave her definition of forced marriage, namely a marriage that comes about because violence is used or the threat of violence, so a marriage that comes about not with their free will. The expert highlighted that none of her respondents experienced violence according to her study. A few cases (which she estimated to be under 10 percent) had given anecdotal statements as to that they would have been killed or that their father told them that he would be killed if they did not marry. Thus, she came to the conclusion that the weddings were not forced. Judge Fenz asked her whether she understood it correctly that she submitted that there had not been any forced marriages in the Khmer Rouge period. Ms. LeVine explained that she thought that the description of Civil Parties of them having been victims of forced marriage were true, but that they were only four individuals from one village in Kampot – which belonged to a region that was known as harsh region. Moreover, in 1978 the regime was harsher. Thus, there were regions that were more at risk for being threatened. “Nationally that was not the case”, she said.

As for a policy of marriage, she pointed out that the function had a higher role than the structure. The structure was about more consistency in how weddings took place in 1978, she said. This related to how people were called up and the ceremony itself.

Judge Fenz asked whether her research related exclusively to those who married under the Khmer Rouge and were still together. She said that this criterion was only those of her first example. Afterwards, it was not specified but they were mostly still together. She interviewed the first eleven couples over a three year period.

Questions Regarding Statistics

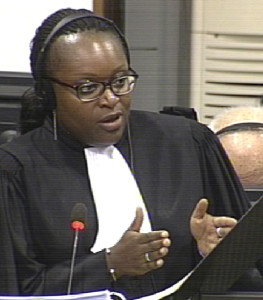

Expert Witness Pen LeVine

Judge Fenz then wanted to know how many people were not together anymore. She replied that there were 24 who were not together anymore due to the death of the spouse and 39 due to separation. Two remarried. Judge Fenz asked whether she had a sample of in which years the couples were married. She replied that 0.02 percent were married in 1975, 0.06 percent in 1976; 26 percent in 1978, and 15 percent in 1979 (which included those after the fall of the regime). It later became apparent that she was confused with the percentages: she had said that 76 of 192 had said they were instructed to consummate their marriage, 19 of who said that they had indeed done so. She said that this equaled 0.09 percent, while it was actually approximately nine percent.

She said most people said that they had no energy and felt ugly and untouchable. They could not imagine being in a sexual relationship with anyone.

She had been in the court audience before. She explained that she had more confirmation of the violation of people’s safety. This had the potential to create more harm. Psychologically and from a spirit-based perspective, the rituals was a violation of those people living and those “no longer living”.

When someone was told that Angkar asked them to get married, “it was essential that they comply”. She turned back to the example of thinking – under the holocaust, she had no one say that they were afraid to think. Men usually considered Angkar to be a person who was associated with the Khmer Rouge, whereas for women, especially when there was no access to protective rituals, Angkar was more perceived as a force.

There was a different response in compliance when force was political than if the force was animist. When she started travelling with them and watched them walk in places of memory and heard them qualitatively, she found them referring to Angkar more as an animist force. The more Angkar was perceived as a transforming, destructive force, the more they complied.

The president announced that one extra session would be granted to all parties combined.

Background of the Expert

She said that she had no legal training. The disciplines that she worked in informed her research. She did not use the terms in their legal meanings. She did not speak Khmer. Around half of the students who helped her with her research were female, and half of them were male. The translators were male and female. She considered the “gender issue” on a regular basis. He asked whether those who fled the country may have had a different view on Cambodia and that she had therefore excluded refugees. She replied that she had looked at cultural practices across three generations and that she wanted to make sure that the sample she chose was not re-socialized in a different social context. Moreover, the traumatic experiences of a refugee camp and challenges in finding a host country would have impacted their perceptions. Ms. Leang asked whether the interviewees may not have wanted to reveal about the consummation of marriage in the presence of their children.[3] Ms. LeVine replied that there was a difference between a Western view of confidentiality and Cambodian view of confidentiality. What she discovered in her studies, men would often speak first, and his wife would speak later. For example, wives would correct their husbands if they misstated something. She had looked at how they came to consensus, but also interviewed them separately.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Getting Married under Democratic Kampuchea

After the lunch break, Mr. Leang inquired about the questionnaire. He asked her to clarify what the translation was used by the interpreter for “real” or “authentic” marriage. She replied that the couples used the term “Angkar” as the organizer of the wedding. She did not know the word that was used.

Mr. Leang asked her to clarify whether those people ever discuss the experience in relation to their marriage during the Democratic Kampuchea period. She asked for clarification, but Mr. Leang moved on and asked whether the interviews were conducted by the children of the interviewees. The “start of the snowball” was a parent of one of the interviews, for example. Thus, the first interviewee could be found through a discussion with the parents. Mr. Leang then asked about traditions and reluctance to speak about sexual relations. She explained that her age and her marital status (she was approximately of the age of the respondents, a widow at the time, and her child was born in 1976) had been helpful for people being forthcoming with information.

She said that fifteen percent got married after 1979. Out of these 15 percent, three people got married in 1979 during Democratic Kampuchea.

The national prosecutor gave the floor to his colleague Nicholas Koumjian.

Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Victor Koppe

Mr. Koumjian asked whether it was correct that she never studied the policies of the leadership. She said that it was incorrect. She said that she “read and pondered” and talked to many historians. She confirmed that she said that the marriages in her sample were not forced. She said that she asked whether they thought that their marriages were “authentic”, and most said yes. Mr. Koumjian asked whether there was a difference between authentic and forced marriage. When she asked for clarification of the question, Mr. Koumjian gave the example of a father who threatened a woman with a gun to marry a man 30 years her elder and asked whether this marriage would not be seen as real. She replied that no one took out a gun to anyone in her sample and that no one was threatened with force if they refused. When Mr. Koumjian asked whether she did not use the legal definition of ‘forced marriage’, Nuon Chea Defense Counsel Koppe interjected and said that there did not seem to be any legal definition in general and that it remained to be debated whether forced marriage was even a crime. Mr. Koumjian replied that it was explained in the Sesay et al. decision in the Special Court of Sierra Leone and asked whether she had studied decisions from that court, in which it was defined that a person “is married under circumstances which are not with consent because of force, threat of force or coercion”. Ms. Guissé objected and said that jurisprudence took place after the facts of Democratic Kampuchea. Judge Fenz replied that the Chamber would discuss legal definitions and the debate was not needed at this point.

Mr. Koumjian consented that he did not present the definition as the definition of forced marriage, but as one possible definition. Under this, he said that “the perpetrator compels the victim through force, threat of force or coercion to serve as a conjugal partner”. She disagreed with the term perpetrator, so he repeated the definition and replaced “perpetrator” with “someone”, and “victim” by “a person”. She said that she needed to “be very careful”, as it would put arranged marriages and forced marriages “on the carpet here”. Mr. Koumjian said that he did not ask about arranged marriages and just wanted to know whether many of the respondents felt compelled or coerced to marry a person they did not know or want to marry. At this point, Mr. Koppe interjected and said that “there’s a total mix-up not only of geographic” but also legally. He said that the situation in Democratic Kampuchea was different to the one in Sierra Leone. She replied that she was unable to say that force was used, but that people lost access to traditional ways of recognition of a wedding.

Impact of Marriages

Mr. Koumjian moved on and inquired about the trauma under Democratic Kampuchea. Ms. DeVine explained that obeying meant an increase in privileges and to have – potentially – some safety. When he asked whether everyone who lived during that time experienced extreme stress, Mr. Koppe objected and said that the expert would be in no position to answer that question. Mr. Koumjian rephrased and inquired whether she would agree that all those 192 respondents lived through extreme stress under Democratic Kampuchea. She said that the level of trauma was immense. She explained that the wedding was a moment of change for them and that there was a chance of change then.

Mr. Koumjian said that she had described traumatic experiences under Democratic Kampuchea. She said that if they received a krama, they would be called out for wedding, and that if not, they may be called for death. Mr. Koumjian asked whether it was correct that “free choice was impossible” and that “protest was impossible” also for marriages.

She replied that she was not ready to answer the question at this moment.

International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian

Mr. Koumjian wanted to know whether to coerce someone into marriage when it was for a national service legitimized it or meant that it was not forced. She said that in the context of Democratic Kampuchea, conscripted marriage was the best term to be found. When Mr. Koumjian asked about the Second World War and whether she would see conscripted sex as sexual slavery, Mr. Koppe objected. Mr. Koumjian moved on and asked why she did not ask in her questionnaire whether they had wanted to get married. She said that she did not want to set in motion an answer that people would perceive she wanted.

She said that she was interviewed by a journalist in the New York Times, who had told her that there was an estimate about a number of women under Democratic Kampuchea. She subsequently found a statement that over 200,000 “comfort women were enslaved by Japanese military”. The statement further alleged that around 210,000 women were forced into marriage if there was an average of two group marriages with 15 women in each ceremony and a population of seven million. This was the first time she had heard the comparison between comfort women and Khmer Rouge weddings for the first time back then; she found the comparison offensive. The association of forced marriage with rape as such was “unfair”.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Coerced or Forced to Marry?

Mr. Koumjian asked whether it was correct that she never read that all of the couples were forced to marry in literature or by the Co-Prosecution. She clarified that the head of the boys-camp and the girls-camp arranged the wedding. Mr. Koumjian asked whether she would agree that the couples went through a period of extreme difficulty together and that this in some cases led them to grow closer together, even if they were chosen to be married together. She confirmed this. “You couldn’t have interviewed someone who […] were killed?” She was interrupted when she started giving a longer explanation, but Mr. Koumjian interrupted her. One of the couples had corrected her when she alleged that they were forced to marry. She did not ask about the consent. She confirmed that she did not know, since she had not asked them, whether they were explicitly forced. She explained that she asked about the safety of the persons. Mr. Koumjian quoted her annex, in which she had said that some feared to be annihilated if they did not agree. He asked whether she would consider that they had freely consented. She replied that the fear of annihilation was different when they had access to protection. If assuming that one had no access to traditional protection, the “fear was extremely heightened”.

Mr. Koumjian inquired whether she considered it a coerced marriage if a person was told that her father would be killed if she did not marry. She explained that she did not want to marry any man and not only the individual, but that she would have for her father.

Mr. Koumjian then probed on the difference between arranged marriages by the family and arranged marriages by the state. She said that they did not question their parents’ choice. Mr. Koumjian asked whether she saw a difference between a family arranging a marriage and a state arranging a marriage and what this did to the individual. Ms. Guissé objected on the use of the term of state.

Mr. Koumjian asked whether she had read a book in which Nuon Chea was quoted. Mr. Koppe objected and said that Nuon Chea had not authorized this book. She had said that she had reviewed the book and that it did not give exact quotations and sources sometimes.

Mr. Koppe inquired about conditions of labor during Democratic Kampuchea. She replied that there was malaria, starvation, or fatigue during hard labor. When he asked whether she considered the threat or forced labor as force, Mr. Koppe objected and said that she could not make comments on legal terms. Mr. Koumjian quoted a few answers, for example “She did not agree, but she was afraid of being killed, and agreed”. He asked whether these were examples of people who did not consent to marry and did so solely under threat and coercion.

She said it was “difficult” for her that her analysis was clustered by way of examples to lead her to a different conclusion. He replied: “your conclusion is contradicted by your research” and wanted her to comment on this. She answered that her conclusion stemmed from her whole of her studies and analysis and that she did not lead the respondent.

Mr. Koumjian moved on and asked why she had no indication for 84 of the subjects whether they were instructed to have sex or not (for men: 88 were told to have sex, 16 were not told to have sex, 42 no indication; for women: 39 were told to have sex, 18 were not told to have sex, 42 no indication). She replied that she was “careful to put down those who indicated positively” that they were asked to have sex. She said that people were mostly told to be loyal and not have more than one partner. In one case, she admitted, one person had been told to produce one child per year. Most of it, however, was related to loyalty to the party.

Mr. Koumjian asked whether she had read in the Revolutionary Flags about the intent to double the population.[4] She said she had read it, but a long time ago. When she first read Ieng Sary’s 1980 statement that weddings should “now be free”, she had interpreted it in the Western sense that nothing should be arranged. She denied that she read it in a way that there was a change of policy.

Mr. Koumjian asked whether it was still her opinion that people could freely exercise their consent to the weddings arranged by Angkar.[5] Mr. Koppe objected and said that the Revolutionary Youth was addressing young CPK cadres. Mr. Koumjian then repeated the question. She did not acknowledge that marriages under the Democratic Kampuchea were done under coercive circumstances against the free consent of those involved: “Because of the way you structured and the sources you used, my answer is no”. With this, Mr. Koumjian concluded his line of questioning and thanked the expert for testifying. “I really hope I didn’t offend you”, he said.

The President adjourned the hearing. It will continue tomorrow, October 12, 2016, at 9 am with the testimony of Peg LeVine, followed by 2-TCCP-298.

[1] E3/1794, at 00482602-10 (EN)

[2] E3/10676, at 01330847-48 (EN).

[3] E3/1794, at 004825228.

[4] E3/16, at 00380647 (KH), 00498284 (EN), 00643891 (FR).

[5] E3/775.

Featured Image: Expert Witness Peg LeVine (ECCC: Flickr).