First Day of Closing Statements for Case 002/01 Hears Statements from Civil Party Lawyers

The gallery at the ECCC was nearly filled today as 478 spectators arrived to observe the start of the Closing Statements for Case 002/01. Judge Nil Nonn, President of the Chamber, addressed the gathering with various housekeeping and logistical remarks. The coming days will follow procedures as set by Internal Rule 94, he said, and each group will read its closing briefs according to the following order and approximate timetable: Civil Parties (1 day), Co-Prosecutors (3 days, including requests for sentencing), Defense for Nuon Chea (2 days), Defense for Khieu Samphan (2 days), rebuttals (1 day), and final statements by the defendants (2 hours each). After the completion of the closing statements on or near 31 October 2013, the judges will adjourn to deliberate on their verdicts.

Judge Nonn reminded the gathering that closing statements should be summaries or rebuttals of other parties’ submissions, and that speakers should be aware of the multi-lingual nature of the proceedings, urging them to speak slowly and clearly.

At the start of the day, both defendants sat with their legal teams, but at 9:15 a.m. Mr. Chea requested to be allowed to return to his holding cell and was escorted from the courtroom.

Closing Statements for Civil Parties Begin

The remainder of the day consisted of closing statements delivered by the six co-lawyers for the Civil Parties, and, at the end, a final statement on the subject of reparation.

Leading off, National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang sought to demonstrate how the defendants are responsible for and guilty of all the atrocity crimes for which they are under trial. Specifically, Mr. Ang reviewed the actions the Khmer Rouge undertook in their quest to accomplish a “massive work of social engineering” which led to an immense death toll. The involvement of the civil parties at this trial, he said, has highlighted the “non-accidental” extent of the crimes committed, and has brought a human dimension to it that would have been otherwise missing. Their testimony included horrific stories that had remained unrecounted, in some cases for 30 years. “It took an impressive degree of courage,” he said, “to face the strain and risk of testifying to this chamber.”

It was at this time that Mr. Nuon requested to leave the courtroom.

Continuing his efforts to highlight the extensive and valuable evidence brought to the proceedings by the civil parties, Mr. Ang said, “It has been a very long wait for justice, a wait which makes these trials historical.” Testimony has come in one of two ways: by written records, and by courtroom testimony. Both means, he said, should be treated as probative evidence for the justices’ consideration since “all evidence is admissible” according to Rule 87.1 and has been properly put before the chamber.

He continued, stating how the written statements show evidence that is of a cumulative nature, and were put before the chamber during the investigation phase in a manner that complies with the standards. They were properly admitted, and so carry weighty probative value. The testimony corroborates other evidence and adds detail and nuance to the overall testimony and documentary evidence set before the chamber. Mr. Ang finished by suggesting that not only has participation of the civil parties represented an important role in these criminal proceedings, but it has also been necessary in adding to the truth of what happened.

Remembering the forced evacuations and restructuring of the social order

Next to deliver his closing statement was Civil Party Co-Lawyer Hong Kim Suon. His remarks centered on a reexamination of the general actions of Khmer Rouge from 1975 to 1979 and the establishment of a “rapid socialist revolution.” Mr. Suon spoke at length about the party’s goals using five policies intended to move forward the goal of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) of social revolution and a new social order in Cambodia.

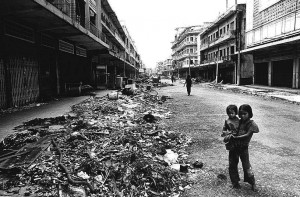

The forced transfer of huge populations from cities and towns and later between rural areas was an on-going example highlighted by most of the speakers today. For his part, Mr. Suon spoke of the CPK’s need to control the population during the forced transfers in order to meet the production and infrastructure demands of the “Great Leap Forward.” Transferees were given little or no advance notice (in some cases only 15 minutes) to walk away from their homes and lives. Compliance was expected and refusals led to increasingly forceful methods for removal. Pleading for more time was useless; Mr. Suon gave several examples, but the primary message was that there was no choice. People were told, “If you decide not to leave, you will be shot to death.”

People were told not to take any belongings because “Uncle will feed you there.” In Phnom Penh there were so many people trying to comply during the evacuation that there were stampedes. People died. Mr. Suon recounted testimony of how transfers were carried out in inhumane conditions. People were often on foot and there was no food, water, shelter or medical attention. Specific vulnerable groups were targeted for persecution. Buddhist monks and nuns, elderly, newborns, infants, children, hospital patients, and new mothers were some of those at especially high risk. The CPK conducted the population transfers without regard for the impact of family separation. Disappearances, starvation, killings, beatings, and sexual violence were commonplace. Mr. Suon specifically tied these atrocities back to the defendant Nuon Chea.

Mr. Suon continued to recount the goals of those in power, which included forced collectivization by 1976. The idea was to establish the “base” people already knowledgeable about farming and the life of a peasant as distinct from the “new” people arriving from the cities and towns who required “re-education” about the new social order. It was “tantamount to an open-air prison” he said, going into a detailed review from the testimony about how traditional family bonds were destroyed, children were encouraged to tell on parents, marriage was regulated and arranged, and so on through a litany of actions taken by the CPK to assert and retain power.

On Security Centers, re-education, killing of enemies, and the targeting of groups

After the mid-morning break, Civil Party Co-Lawyer Sam Sokon approached the bench to deliver his closing statements. His focus, he said, would be upon the security centers established by the CPK to insure that the principles of the revolution were strictly respected. A part of this initiative involved abolishing the existing class system so as to emphasis the value of workers and peasants by eliminating the oppressive (educated) classes. A second initiative (started at the outset of the regime) that Mr. Sokon reviewed was the effort to re-educate “bad elements” and kill enemies. Anyone who interfered was considered an enemy). Anyone who violated the code of conduct was considered an enemy. Mr. Sokon gave one example of what was considered an immoral act (sexual relations by an unmarried man with a woman), and thus “enemy” activity. If not killed, then such enemies were “re-educated,” which meant detention at a Security Center where torture and killing of enemies was a frequent result.

The long-term consequences of these policies on civil parties, said Mr. Sokon, are significant. People today continue to suffer from mental problems and anguish, nightmares and constant mental suffering from witnessing the atrocities they saw.

Part of the reasoning behind some of the policies about enemies, said Mr. Sokon was to identify targeted groups, such as those related to the former Khmer republic, civil servants, soldiers, and their families. The objective was to eliminate the former order so as to create a collective society in which classes, religion, and culture would be eliminated. All levels of the social classes had to be dissolved, and only two classes were to emerge. This operative carried the additional assurance that no opposition to the new regime would be able to form. All remnants of the old society had to be cleansed, which led to the arrest, interrogation, and killing of many people.

Also, he went on, the Cham people in the eastern areas of the country were similarly targeted for elimination. Buddhist holy people were disrobed as well, all in an effort to seek homogeneity in the Eastern provinces. Religious practice was considered reactionary and thus not allowed. Ethnic minorities (such as the Cham people) were prevented from religious practices such as praying to their ancestors’ souls, or offering food to the dead. Monks were asked to leave the pagoda and disrobe, and become soldiers. Holy books and other religious items were searched out and destroyed. They were not allowed to wear traditional dress, or organize funerals or traditional marriages. Pagodas and Buddhist statues were destroyed. Mosques were turned into warehouses & pig pens. People had been forced to eat foods proscribed by their religions. All religious leaders were lost such that, according to Sokon, there is an ongoing sense of loss still today, and lack of elders to teach about these traditions.

Srinna offers additional basis for justices to consider when rendering justice

In a brief statement just before the lunch break, Civil Party Co-Lawyer Ty Srinna offered the justices thoughtful points regarding three factual elements of the forced evacuation, Phase 1. The goal of her written brief is to provide the chamber with some additional basis to consider when it comes time to render justice to the civil parties and the witness/victims of the regime. She promised not to touch on points already submitted earlier.

Forced evacuations were not confined to Phnom Penh, but also included other provincial towns (which she listed), and also the subsequent transfer of persons from one place to another. During all phases and locations of evacuation, she said, “all were traumatized; they suffered directly from this transfer.” She recounted vivid scenes of people being killed, having to look at dead bodies (especially those who were a result of execution). She recounted what life is like today for the orphans and other survivors who are experiencing sometimes debilitating and on-going psychological suffering and PTSD. The trauma of these survivors must be acknowledged.

Due to the trust in this tribunal, thirty-two civil parties have come to testify before this chamber. These civil parties and witness/victims insist on punishment of the defendants. And yet the co-accused have spoken little on what they ordered, she said, They deny knowledge of the crimes that they have committed, when Khmer Rouge troops employed various means including threat of life, at gunpoint. Former officers of the former government were searched out and arrested. Some civilians classified as “new” civilians, were placed by the troops under a form of deferential treatment when they reached their destinations.

Ms. Srinna also spoke to a submission by the defense team that touches on several points regarding the forced transfer of people during Phase 1. The defense has attempted to tie the forced transfers to a shortage of food and lack of security in April 1975 and they have argued that this was caused by the contemporaneous conflict in which the Khmer government was the target of overthrow by democratic Kampuchea. “I consider this as an utterly unreasonable point,” asserted Srinna, arguing that the issue of a food shortage and lack of security in the early days of this regime is not a plausible excuse. Even though the situation in Phnom Penh was a result of the preceding conflict and despite the shelling of the city, “the livelihood of people could continue, they could perform their jobs, and so on,” she said, “Food supplies were still sufficient.” It was the Khmer Rouge who prevented the transfer of food into Phnom Penh during that time and efforts to provide international assistance were denied by the Khmer Rouge government. The assumption that lack of food was the reason for the evacuation was not plausible, she stated. If this was the case, evacuation should not have been done in such an emergent, coercive manner.

“If the intention was to protect people from starvation (as they asserted),” said Srinna, “they would have done something for the people, but they did not do that. On the contrary, they did not address the lack of food even when people were evacuated to the countryside. Surely it was their pretext for evacuation.”

The issue of security and the infliction of fear

Regarding the issue of security, the Khmer Rouge used the message that there was an imminent bombardment by America. Ms. Srinna made the point that no evidence had shown that bombardment was, in fact, imminent. They would have known of the likelihood of an American bombardment. The Khmer Rouge soldiers merely mentioned there “might be” or “it is likely” that America would bomb the city, but testimony shows that this was an invented message in order to coerce people in evacuation.

And so, she said, “the creation of a situation of panic was an effective means to evacuate people out of Phnom Penh.” Trauma from earlier in the 1970s that led to 130,000 refugees was helpful, but really “this was a strategy, a pretext, to get people to leave the city. It was a very unfortunate message, a propaganda that they used in order to inflict fear on the civilians as well as soldiers who wondered if the government could still protect them,” said Srinna,

Another issue deserving clarification is the policy of separation and segregation to inflict fear on the people, continued Ms. Srinna. The goal was clear: to reduce the numbers in groups on different pretexts. They started to segregate members of a group, with daily losses, most people dying as a result of lack of food or medicine. No witness stood up to reject this reality.

And also, she pointed out, the defense spoke about how the “new” people could not adapt to a new life. To civil parties, this is an unacceptable point. The testimony of civil parties and witnesses provided evidence regarding the sustained and harsh conditions imposed on them, and that it was of a degrading nature. They had to adapt to a new livelihood after a long journey. The new people were not used to this life and often did not have the skills to construct shelter or work in the fields, said Ms. Srinna. Mistakes were deserving of punishment, and new people made mistakes. It was not right to compare the performance of the work of new people and base people. It was an issue of adaptation, and yet people continued to disappear without reason. Infliction of fear was a common theme that, she argued, “led to the dramatic experience of the witnesses and civil parties.”

Complex questions with no simple answers: Martineau speaks

At 1:30 p.m. after the lunch break, Civil Party Co-Lawyer Christine Martineau stood to address the bench, framing her commentary around the value of these proceedings on the civil parties.

To begin, she said, “Time has not erased these wounds but a question is still there: why? To such a complex question there cannot be a simple answer.” She asserted that it has been through the testimony of the civil parties that the court has been able to “discover the true nature of this regime.”

Addressing the defendants, she suggested to them that “your excuses in saying you didn’t know what was going on” were not valid. “When we read through your answers to the civil parties, we see that you are a lot more than a puppet president. Before and after the DK regime you were in the party, you followed Pol Pot up to his last days. You never distanced yourselves from him. Who do you think you would convince of your true responsibilities?”

The Civil Parties will not be deceived, she said, and in the end, she asserted that it “all shows that your crimes are crimes against humanity.”

This is work not only of justice but also remembrance

Martineau continued in a forceful voice how civil parties got through their experiences in 1975-1979 in one way. “The heavy mantle of silence was their only means of surviving so many horrors,” she said, but now there is no longer room for deceit or silence.

She continued addressing the defendants directly, speaking of their ideology and how they managed to format so many minds and thus exert social control on the people. She spoke of the hallmarks of a totalitarian regime and how the defendants sought to eradicate the culture of the people. The deception on 17 April 1975 that peace had arrived, that the war was over, was cause for rejoicing. But “these urban dwellers could not imagine what was going to happen to them. People rallied behind your cause. They were programmed to execute your plan,” she said.

Martineau then led the assembly through a narrative of the historical events, speaking of how deceit goes hand in hand with secrecy, and that it was “a major hallmark of your regime.” Martineau spoke of secrecy as an instrument of power and how it became possible to deceive two million people and put them on the streets for days without food or water. “Was that your way of cleaning up the town?” she asked.

Continuing her evocative narrative of the actions and emotional impact of those actions, Martineau referred to the fact that such an immense situation had to be orchestrated. “The order is from above,” she said, referring to the illusive entity known as Angkar. People were treated worse than animals, and even if the defendants didn’t visit those places “it was not the little chief who created those orders. They obeyed your orders,” she asserted.

To finish, Martineau said to the justices, “During these proceedings you have given back the voice to the Civil Parties. This voice bears fruit and you will find that in your deliberations.” And she sat down.

Simmoneau Fort continues the theme with her closing statement

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Elisabeth Simmoneau Fort stood next. She began with some reflection of her three years in the room. On her first day, she said, 35 years after the time period being examined in these proceedings, she wondered if she was doing the right thing. This led her to reflect on a duty to all the victims from those years, and, she said, “it is to them, the victims, we owe the deepest respect, compassion and most certainly justice. I don’t regret that moment of doubt.” This day in which the Civil Parties are offering their closing arguments is “a key moment of international justice, because for an entire day it is the victims who are in the limelight and it is their rights that are being highlighted and protected.”

With that, Simmoneau Fort went on to look back on the 214 days of this trial and upon the witnesses, “attentive, drowning in obtuse details, always expecting truth, an explanation, an answer, a meaning however imperfect and incomplete.” She spoke of her admiration for the courage and resolve of the civil parties and acknowledged “how painful, how repugnant it must be to have the feeling you’re not being believed.” It was right, she said, to take the risk.

“This trial cannot meet all expectations. It is true that justice like any human enterprise cannot meet the entire range of expectations and desiderata, but it will not have been in vain, whatever the outcome.”

Simmoneau Fort stated that he two objectives for the civil parties have been to have the culpability of the accused recognized and to find recognition of the harm they have gone through met with the necessary reparation.

To the justices, she said, “What you are judging through the eyes of these victims is emblematic of the entire DK regime.” The benefit of hindsight has provided the chance to realize how at the time those events “defied the imagination, exceeded belief and expectation.”

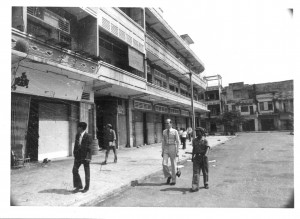

Nobody really believed it could happen, but in three days the town was emptied. After giving anecdotes from witnesses, Simmoneau Fort suggested that the scope of the operation was so effective and radical, it could not have been the work of a “handful of petty chiefs.”

“Without doubt, this evac had been carefully prepared, thought over, and practiced elsewhere,” and she went on to say that the victims “didn’t know they were caught in a plan hatched months or years ago, that the displacement was only the first, in a phase of a huge, criminal plan.”

Speaking in the present tense, she continued to draw listeners along a walk down the memory lane of horrors experienced as people realized over time that they would suffer a great deal more, and for a very long time.

Simmoneau Fort delved into several conditions that were necessary to the plan:

- Fear – always a lethal weapon, you just have to spread it everywhere;

- Thirst, but more particularly, hunger – an obsession that became physical and psychological torture;

- Total material dependence – People were told not to take anything more than what they’d need for three days, and those who took more but then had to dump or barter those possessions. Having nothing means losing your individually and your autonomy. It also meant eliminating the tokens of free thought, such as glasses.

“Imagine how indoctrinated you have to be to repeat such idiotic schemes,” she said.

Collectivization as the next strategy

Simmoneau Fort continued her dialogue with reference to the use of collectivization as another instrument used by the regime. Even the language changed to more warlike phrases. The “enemy” was introduced—and it was everywhere, even inside oneself. “Hundreds of documents echo this word,” she said. There was no “I” only “we” but this was not a haphazard creation. Propaganda was an omnipresent, crucial vehicle, and Nuon Chea was in charge of propaganda.

Another effective instrument of the regime were the children. “How did they do it, turn them into such a potent weapon?” she asked. They were there as among the first victims, charged with emptying the city, afraid of what would happen if they didn’t. They learned to disown families and disobey their parents.

At this point, Judge Nonn called the mid-afternoon break. Afterwards, Simmoneau Fort continued to speak of the instrumentalism of children.

“Is there any proof of all this?” she asked but then went on to assert that when descriptions of identical scenes from throughout the country are heard, when you hear victims repeating the same discourse, when the words you hear are precisely the same things, it is a form of proof that is terrifyingly effective. “Wherever these people are, their testimony is identical. It is the same. They have lived through the same experiences, have undergone the same living and moving conditions, have heard petty leaders giving the same speeches-what better proof can there be of a common plan?” she asked.

Why the defendants do not speak

Simmoneau Fort turned her attention to the fact that the defendants said at the beginning they were looking forward to addressing themselves to the people. However, apparently on the advice of their counsels, “they have taken refuge in silence,” she said. “This is regrettable. People have been looking forward to hearing the reasons, how they made the decisions, forged the policies.” There is a sense of entitlement, expecting the leaders to give some sort of account of themselves.

“The accused repeatedly said they didn’t know what was going on and that what happened was not what they intended,” she said, blaming this on denial. “What was going on? What are they talking about? Or should I say, what is it they aren’t willing to talk about?”

In conclusion, Simmoneau Fort reflected once again on the larger picture. “These are crimes against humanity, the gravest crimes, because there were murders, extermination, persecutions and other crimes connected with forced transfers and forced disappearances. A good many civil parties will not have their stories told, may not get to be heard, but these debates and testimony have proven to be positive elements that have provided substance and reality (a sad reality) to the history of this country.”

Again she listed the various aggrieved parties, and then said of them, “I hope we can visualize them trying their best to adapt to this absurdly cruel regime with no respect for their dignity. That is the reality that underpins this trial.” Of the accused, she finished with this: “They organized it, they built it, they extended it all across their country for eight years and twenty-five days to serve their glorious revolution. I hope justice will condemn them for organizing all of that.”

The call for reparations

Simmoneau Fort than turned her attention to the matter of the civil party’s requests for consideration of judicial reparations. Acknowledging that the accounts as given by civil parties “went beyond imagination regarding the inhumane treatment they endured,” Simmoneau Fort spoke to the extent of their dignity and moral strength. Those who testified knew they were speaking for everyone who suffered and that they were entrusted with the essential duty to bring the truth to light, she said.

“Reparations should amend the harm done,” she said, “but also that it is impossible, especially at such a degree of gravity.”

After listing many elements of the harm, she continued, “It is clear that we will never be able to amend the harm caused. However, we must make sure that real reparations of real value should be awarded.”

The question of what to ask for is part of a logical conclusion of the trial. Conviction with an award of reparation is a possibility. But beyond development of projects, and funding them, she said, “We are requesting the chamber not to omit the responsibility of the guilty in the reparation process, in the case of conviction as well as the funding of the projects.” And, she asked that the chamber rule that any reparations be allowed continue beyond the duration of implementation for budget constraints so additional funding can be obtained. In closing, she said, let this serve as an “expression of our conviction that just and meaningful reparation be an essential part of any meaningful conviction.”

Final statement on Reparation

Mr. Ang again approached the podium to review the reasons and grounds for reparation in line with Internal Rule 23.1.

After a brief review of the horrors visited upon the civil parties, Mr. Ang informed the court that the reparations plan includes thirteen projects in three groups. The groups are:

- Remembrance and Memorialization. In this group, the suggestion is to name a specific memorial day for people to gather and remember the events of the years 1975-1979. Governmental permission has been sought at the request of the civil parties. There is also a plan to create permanent public memorials, perhaps as an initiative where those who wish to can deposit the remains of the dead, or to be a place to come and pay respect.

- Rehabilitation. This group includes two initiatives. The first is testimonial therapy and the second are the creation of self-help groups.

- Documentation and Education. The goal is to build/compile documentation and educational methods in collaboration with The Documentation Center of Cambodia and partners to promote education and organizing exhibitions to be implemented in the provinces.

Ang detailed the various projects and funding sources that have already been secured to support these reparatory goals, and mentioned many proposed undertakings that could further advance them.

Conclusions to the day

Mr. Ang completed his list of sought-after reparations for consideration by the court by suggesting that as a consequence of the crimes that the accused committed, the civil parties hope the chamber agrees that it will follow direction of the Chamber per Rule 23.3.b). The Civil Party team also requests that the trial chamber consider leaving open the opportunity to secure additional funding during deliberations should the civil parties be granted the opportunity. For recognized projects, there is the hope that all can be implemented. Finally, the civil parties will endeavor to work with other partners and the international community for funding.

This ended the closing statements for the Civil Party, which was noted by Mr. Nonn as being done within time allocated. Closing statements by the co-prosecutors will begin at 9:00 a.m. Thursday, October 17. The court was adjourned at 5:05 p.m.