Nuon Chea Defense Counsellor Questions Tribunal’s Fairness and Legitimacy

Closing statements for Case 002/01 turned today to the defense for Nuon Chea. Upon completion of the normal salutations, Victor Koppe, Co-Lawyer for Nuon Chea presented a roadmap of the analysis he and his team will present. This first of two days of statements will begin with an overarching commentary questioning the general importance and fairness of this trial and the general legitimacy of this tribunal. Then, Mr. Koppe’s colleague, Son Arun, Co-Lawyer for Nuon Chea, will deliver a presentation of their client’s background and role in Democratic Kampuchea (DK).

After a mid-week day off for a national holiday celebrating the Paris Peace Accords, Mr. Koppe said, the team will focus Thursday on the facts of Tuol Po Chrey, the evacuation of Phnom Penh, and the alleged second forced transfer. Thursday’s plan also includes an analysis of living conditions in Cambodia in 1975 and how supplies and medical care were in crisis and the country was already on the verge of a full-fledged catastrophe (one that began in 1972, “long before the CPK took control of supply lines.”). By 1975, said Mr. Koppe, the Cambodian economy had been devastated by American bombing and before April that year, the U.S. government was already predicting widespread starvation, especially in Phnom Penh.

After a mid-week day off for a national holiday celebrating the Paris Peace Accords, Mr. Koppe said, the team will focus Thursday on the facts of Tuol Po Chrey, the evacuation of Phnom Penh, and the alleged second forced transfer. Thursday’s plan also includes an analysis of living conditions in Cambodia in 1975 and how supplies and medical care were in crisis and the country was already on the verge of a full-fledged catastrophe (one that began in 1972, “long before the CPK took control of supply lines.”). By 1975, said Mr. Koppe, the Cambodian economy had been devastated by American bombing and before April that year, the U.S. government was already predicting widespread starvation, especially in Phnom Penh.

In addition, he said, the defendant Nuon Chea intends to speak to the court on Thursday.

Mr. Koppe foreshadowed the tenor of his comments by stating at the outset that the evidence about Toul Po Chrey is “limited, inconsistent, and confusing,” and that “whatever happened, it was not attributable in any way to my client.”

“What has gone on has not been a trial at all,” he asserted, “in the sense that we as lawyers normally understand it. It has been a showcase of the conclusion that everyone wanted and expected from the day the tribunal was constituted.”

To conclude his overview, Mr. Koppe said he would show that the co-prosecution’s treatment of the evidence is “selective and seriously misleading.”

A critical review of the tribunal’s procedures and processes

Mr. Koppe then spoke for nearly two hours (with an intervening mid-morning break) about the defense’s perceptions regarding the workings of the tribunal, the legal process, and the ideal of fairness to all parties (in particular, his client). He stated that in general, procedures, including the manner in which present case was conceived and investigated, have failed to meet proper standards.

On the topic of the fairness of this trial and legitimacy of this tribunal, Koppe was unambiguous. Since the day Nuon Chea was arrested, “the procedural irregularities have been so persistent and troubling that we have hardly had time to object to them all,” he said, adding that he is also concerned about the government’s control over the proceedings.

Koppe then addressed certain general, “big-picture” themes which had the common thread that “no one at this court is interested in ascertaining the truth. The court was not established for figuring out what happened in Democratic Kampuchea (DK). It was established because people thought they knew what happened and who was responsible, and so they created the court for the purpose of punishing those people before this building even existed.”

He continued, “I can feel the reaction of the public gallery thinking that, ‘that’s because they are guilty. Why should it matter if there were some problems with the process? Nuon Chea is guilty anyway’.” But to a lawyer in a court of law, he maintained, procedural law always matters. The ECCC was created in the pursuit of a fair trial in Cambodia.

“We are interested in a fair, independent, impartial tribunal. If we cannot accomplish that, this exercise is pointless,” he said.

However, he continued, there remain real and unresolved questions about Nuon Chea’s responsibility for crimes as charged in this trial. “Even after three years of investigations and two more years of a trial, the evidence is astonishingly thin. The evidence is just not true. No matter how many times the co-prosecutors call the evidence overwhelming, the evidence is laughable.” The remainder of the defense’s time will largely be spent proving this assertion, he promised.

A concrete example of an untrue but pervasive assumption Koppe pointed out was that the CPK set out to systematically kill anyone associated with the Khmer Republic. He attributed this misinformation as “becoming accepted gospel” as the result of believing some early writings by Francois Ponchaud which the author then acknowledged stemmed from a small, unrepresentative sample of interviews. “Yet once that idea became embedded, it became impossible to dislodge. It became an echo chamber. Eventually, it came to a point that everybody ‘knew’ that it happened, everybody knew there was no evidence to the contrary. I invite the chamber to compare our submissions of the CPK treatment of those soldiers with those of the co-prosecutors and you will find our submissions are far more detailed and specific.”

Koppe accused the co-prosecutors of making many such sweeping claims based on no evidence, invoking “vague CPK theory that says nothing. According to him, they deliberately chose not to discuss direct evidence of Nuon Chea’s intent. Their argument “does little more than recycle and perpetuate longstanding assumptions of what the CPK must have done, because,” he said, “we all know the CPK did bad things and we all know that the CPK had total disregard for human life.”

The emergence of the term “slave state” and other simplistic language

The defense then began to hammer away at the prosecution’s argument as Mr. Koppe continued: “Your honors, the actual evidence of our clients for actual crimes is so limited that the strategy of the co-prosecutors is instead to persuade the chamber that the senior leaders of the CPK were monsters. They tell horrifying stories about the experiences of individual people without even claiming the stories reflected CPK policy. They use inflammatory and simplistic language to summarize and mischaracterize historical events. They quote selectively from CPK documents, failing to mention that those same publications instruct cadres to treat new people and the bourgeoisie well and with respect.”

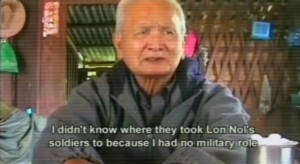

Mr. Koppe used as an example of the prosecution’s “selective use of evidence” by wading through the Teth Sambath interviews and proceeding to “selectively hand-pick the small handful that sound inculpatory, and play them back ad nauseam” when, he said, there is far more in those interviews that he deems exculpatory. He demonstrated his point by playing the full five minutes of a video clip from which the prosecution had taken a small sample, to point out the difference in the contents once the larger context was shown. In the video, Nuon Chea said at the time he didn’t know anything about the widespread killings, and had he known, he would have ordered countermeasures against them.

Mr. Koppe used as an example of the prosecution’s “selective use of evidence” by wading through the Teth Sambath interviews and proceeding to “selectively hand-pick the small handful that sound inculpatory, and play them back ad nauseam” when, he said, there is far more in those interviews that he deems exculpatory. He demonstrated his point by playing the full five minutes of a video clip from which the prosecution had taken a small sample, to point out the difference in the contents once the larger context was shown. In the video, Nuon Chea said at the time he didn’t know anything about the widespread killings, and had he known, he would have ordered countermeasures against them.

Koppe asked the court, “What was my client’s incentive for lying about this? Nuon Chea is 87 years old. He is close to death and knows he will die in prison. He concedes he was Deputy Secretary of the CPK. He concedes he agreed with and participated in the evacuation of Phnom Penh. He concedes that he agreed with the decision to execute the super-traitors. He concedes that he knew of the decision to execute Sow Phim, his oldest and closest friend. Why would he concede those facts and deny knowing about Tuol Po Chrey, and why would he concede his role in the first population movement and deny his role in the second forced transfer?”

Next, Mr. Koppe asserted that the prosecution has misled the court through simplification of the complex historical events pertinent to the trial. For example, he pointed out how the term, “slave state” is misleading and “useless as a means of understanding Democratic Kampuchea and most especially the intent of CPK policy.” He pointed out that the term entered trial lexicon (six years into the ECCC process) only six months ago, on May 8, 2013, when it appeared to be invented during the testimony of Mr. Short. The defense decried Mr. Short as a person who “set foot in Cambodia for the first time in 1993. He began his research on the CPK in1999. He speaks or reads no Khmer,” said Mr. Koppe. “Not a single writer observer or academic or firsthand witness of the events in DK has ever employed this phrase. Yet the co-prosecutors tell us Short’s opinion is the best description available of the CPK’s purpose. Not the CPK’s own circulars. Not Pol Pot’s speeches. But the uncorroborated opinion of a British journalist who entered Cambodia twenty years after the fact and who doesn’t speak a word of the language.”

The defense continued the question the nature of the sources of information obtained by the prosecution and how it has twisted the actual facts of the history and actions of the CPK from a political entity with clear social purpose and political objectives that was fighting for a clear cause to a criminal entity whose purpose was to create a “slave state.”

Mr. Koppe reviewed the co-prosecutors’ analysis of the evacuation of Phnom Penh that the purpose was to punish the urban residents, when the defense asserts that his client’s purpose was to implement rapid socialist revolution and reform Cambodian economic policy. “Have we and the co-prosecutors been trying the same case in the same courtroom over the past two years?” asked Mr. Koppe. His client was less a criminal than a man who was second in command of the CPK, part of a communist revolution, a movement designed to “restructure the modes and methods of economic production, to implement collectivist economic policy. That’s why they exist. That’s what they do. And even the Closing Order says that the alleged purpose of the evacuation was to populate the CPK’s collectivist cooperatives.” Mr. Koppe accused the prosecution instead of depicting the CPK as a lawful political movement of instead “constructing a fictitious, one-dimensional entity infused with criminal intent.”

Questionable sources and the $41 trial

Mr. Koppe then turned his remarks to the questionable nature of the sources relied on by the co-prosecutors, in particular the use of secondary sources. Using them for key allegations is “highly problematic.” For example, a formal analysis of recent evidence showed that in a single day the pros cited Phillip Short’s work 17 times, “like I said, a British journalist with no apparent expertise, a writer no better versed in the facts than the court itself.” That reliance, instead of using genuine firsthand documentary evidence, “is integral to their effort to simplify the story of DK,” said Mr. Koppe, “because secondary sources offer prepacked conclusions.”

He then accused the chamber of favoring testimony only from sources least sympathetic to the CPK. He pointed to the selection of Elisabeth Becker and Phillip Short as expert witnesses (“journalists with no Khmer language skills and no academic credentials”) and their combined two books and selection of newspaper articles about Cambodia. He remembered that the chamber then declined to call Michael Vickrey (“an academic fluent in spoken Khmer who first arrived in Cambodia in 1961 and authored numerous academic publications about the Khmer Rouge”) whose shortcoming would, said Mr. Koppe, “appear to be that he is a communist.”

Mr. Koppe said the defense had sought the use of other expert witnesses but “whose opinions did not complement the standard view of the ECCC” who were similarly rejected.

Mr. Koppe then examined the types of claims the prosecution’s expert witnesses made. For example, he referred to Sydney Schanberg stating that the shelling of Phnom Penh was “psychological warfare.” He accused such evidence as “ludicrous.” Another article published in the New York Times by William Goodfellow who argued the evacuation was justified because of the food crisis in the city. “Now, should we resolve this legal dispute through a debate among New York Times journalists?” he asked, or by other academics writing 30-40 years after the fact.

“This is an outrageous approach to proof in a criminal trial,” said Mr. Koppe, reasserting his view that secondary sources are not as valid as firsthand reports. “Mr. President, if this were the way to conduct a criminal trial, we could have saved a whole lot of money for the international taxpayer. We would not have had to spend $200 million on judges and lawyers. Mr. Short’s book is available on Amazon.com for $20.75. Stephen Heder’s book can be had for $16.50. We could have conducted this trial for about $41. We presume, or at least we hope, there was a reason we did not do that.”

Book lists and bombs

Mr. Koppe then stepped back to take a look at the history of the CPK, and the co-prosecutors’ simplistic view of it. He wondered how the reports of the CPK leaders reading work by Stalin and Mao in their youth served as frameworks for their points of view. “Are the co-prosecutors implying that because the CPK leaders read a book by Stalin in 1953 that they acted like Stalin in 1975?” asked Mr. Koppe.

There was other background information claimed as relevant or irrelevant by the prosecution he wanted to hold up, such as the CPK’s development of policies against enemies. These were framed no doubt to some extent by their reading of Lenin and Mao, but, in fairness, also no doubt by the actions of the “American imperialists (who were in the process of dropping more bombs on Cambodian soil than all of the bombs dropped by all of the Allies in WWII combined),” he said. “Apparently, the co-prosecutors think that the senior leaders of the CPK were worried about American intentions, not so much because the Americans spent eight years bombing them into oblivion, but because, in 1953, they read a book.”

Mr. Koppe then invited the listeners to imagine a trial set up to try George Bush and his government’s lead up to and responses to the events of September 11, 2001, and the resulting conflicts. Drawing an explicit parallel between the way Mr. Bush acted and the events before the court, Mr. Koppe asked, “Would it make sense to anybody? Would it be fair?”

Returning to the theme of simplification, Mr. Koppe compared the Cambodian experience of being bombed, and the resultant catastrophic impact on rice production and this food shortages, with the desire of the CPK to establish adequate agricultural production. Although, he said, the prosecution hopes the use of the word “slave” can transform the purposes of the CPK to suit the needs of the trial, “the overwhelming majority of the evacuees [from Phnom Penh] were farmers who wanted to return to their farms.”

“How dare the prosecutors think they can reduce the concept of cooperatives into one word: ‘slave’?” he asked. He accused the prosecution of an obsession with displayed the CPK as it has, rather than as an effort to rebuild Cambodia without the negative interference of outside forces.

Mr. Koppe then described for the court the facts of the matter regarding control. “Even before Apri1, 1975,” he said, “there were two quite powerful factions in the CPK.” It was not simply a hierarchical, top-down regime with Nuon Chea and Pol Pot at the top of a highly-structured pyramid. He accused the co-prosecutors of ignoring that others, backed by the Vietnamese and others backed by members of the present Cambodian government played a hand. They “simply accuse Pol Pot and Nuon Chea of paranoia and being obsessed by enemies and conspiracy theories. Section and zone leaders did act autonomously, he reported, and some were leading and founding members of the CPK. “The CPK was not a unified entity,” said Mr. Koppe. “There was a real and ongoing struggle for control within this party.” He said that Nuon Chea was right to warn his fellow members of the Standing Committee to be vigilant, especially about people who were fleeing to Vietnam. During the years of the DK, there was conflict verging on outright war going on throughout the country, and people were purged. “Why was that necessary if Pol Pot and Nuon Chea were able to exercise control over an obedient apparatus?” He said, wryly, “all of Pol Pot’s paranoia came to pass exactly in the way he feared it might.”

A verbal indictment of today’s Cambodian leadership

In the next series of commentary, Mr. Koppe departed from his stance that the prosecution is guilty of telling a “simplistic, naïve, occasionally absurd story about DK,” and segued into territory bringing matters to the current day. In his remarks, Mr. Koppe directly accused prime Minister Hun Sen, President of the National Assembly Heng Samrin, and President of the Senate Chea Sim of active roles in carrying out the criminal policies of the CPK.

In Mr. Koppe’s direct words, there have been:

Conscious efforts by the stakeholders of this tribunal to deflect blame away from anyone who might share responsibility for the suffering of the Cambodian people and onto the two remaining accused seated in this chamber. There are many targets whose culpability has never been adequately considered by this tribunal. These include the Americans, Prince Sihanouk, Lon Nol, and the French.

But it is clear that in terms of direct relevance to these proceedings, one rises above the rest: that target is of course the senior leaders of the Cambodian People’s Party, who continue not only to steal elections, land and natural resources from the Cambodian people, but also to obfuscate their direct and active role in the events for which Nuon Chea presently stands charged. If Democratic Kampuchea was a giant criminal enterprise whose fundamental purpose was to enslave the Cambodian people, then each of the three leading members of the current government bears responsibility for furthering that purpose.

As such, there is hardly any doubt of a simple reality. However easily these men are able to shield themselves from criminal prosecution, their liability rises and falls with our client. If Nuon Chea is guilty, so too are they. If Nuon Chea enslaved the Cambodian population, then these three men whose faces hand everywhere on posters in Phnom Penh were his loyal executioners.

Mr. Koppe ended with the assertion that the “direct complicity of the current government is of direct significance to Nuon Chea’s culpability” and which probably helps explain, he said, “why the Prime Minister is openly opposed to investigations of anyone beyond the accused.”

Accusations of barring the defense from developing a credible case

Mr. Koppe then addressed the defense’s on-going difficulties at gaining a fair advantage regarding various legal procedures. He accused the years of investigation as being “shrouded in secrecy,” during which time the defense was repeatedly blocked from building its case. He reported being excluded from investigative hearings, being blocked from doing their own investigations, not being provided with what evidence was being gathered. The defense teams “were instructed to sit on their hands,” he asserted. Yet the evidence they finally gained access to shows leading questions, numerous irregularities, and “outright inaccuracies.”

The flaws in the investigation, according to Mr. Koppe, culminated with the Closing Order, “which does not read as anything but an argument in favor of Nuon Chea’s guilt,” he said. “The word ‘credibility’ does not once appear.” Conclusions were made based on uncorroborated facts spoken by incredible witnesses, in the eyes of the defense, and findings were unsupported. “It was all evidence designed to find guilt.”

“For a trial to be fair, the investigation upon which it rests must also be fair and impartial,” said Mr. Koppe. “Our client’s rights hung in jeopardy even before the trial proceedings began.”

He also accused the trial chamber of failing to remediate the “profound flaws” in the judicial investigation. The most serious failure he cited was the refusal to call Heng Samrim, who would have been Nuon Chea’s best, perhaps only character witness, especially with regards to Nuon Chea’s treatment of Lon Nol personnel.

“In our view,” concluded Mr. Koppe, “there is a deeply ingrained bias on behalf of the prosecution.” There followed detailed examples of this bias and unfairness, and accusations of failure to check the authenticity of much of the testimony that was allowed. Mr. Koppe also expressed frustration with such situations as, when his team tried to question something, being told they should have asked about it during the investigation, when their hands were, effectively, tied. There were also examples given of inconsistent rulings regarding whether witnesses could, or could not, review their notes. Mr. Koppe particularly noted the multiple and, to his point of view, conflicting roles of Stephen Heder in the trial.

“We were frustrated at every turn,” he said. It was the court’s continual barring of defense efforts to build a credible case, he said, that prompted Nuon Chea to retract his decision to resume testimony.

Government interference with the work of the tribunal asserted

For a half hour after the morning break, Mr. Koppe continued giving examples of his team being thwarted by the judicial process from building a credible case for his client and then turned his attention to the matter of government interference with the work of the tribunal. Such interference, he said, “began with the tribunal’s inception, continues today, is documented, and is reliable.” He listed various examples, such as the fact that certain key witnesses (including the late King Father) have been prevented from appearing, and the Prime Minister’s efforts to thwart cases 3 and 4 of this tribunal from ever being heard. He offered the evidence that one judge for the tribunal resigned, citing the government’s persistent interference with his work. Mr. Koppe believes such interference has direct bearing on his client’s right to a fair trial.

Worse, he inferred, is that the trial chamber has taken no remedial action to these injustices. “With each manifestation, Nuon Chea’s right to a fair trial has been eroded until nothing left remains,” said Mr. Koppe.

Koppe questions what the trial is really about

This led to commentary about the overall legitimacy of this tribunal. Mr. Koppe said, “The urgency of making these comments has increased as the prosecutors’ comments grew to a fevered pitch in the last three days. We were assured that this trial is not about communism or socialist or other political philosophies, but what we saw can only be described as an all-out ideological assault against communism for communisms’ sake. If this trial were only about crime, then what we heard for the past three days would have focused on facts, on Nuon Chea’s intentions to execute Lon Nol soldiers, on the evacuation of Phnom Penh. But what we got was a most passionate effort to delegitimize the CPK movement, that it was a criminal organization.”

Mr. Koppe then proceeded to wonder about who were the real winners and the real losers, and whether this is a victory of justice or more honestly an indictment of communism couched in an effort to find criminality from the DK years. Perhaps, he hinted, the real purpose includes justifications by such entities as the imperialist Americans and other governmental foreign policies in order to “absolve them of the crimes they committed in freeing the world of the communists. It justifies their continuing claims to power. For there to be international criminal justice, a trial cannot be free of the suspicion that they’re being used as a tool of political power, used as a method of limiting one side.” He also inferred, related to the ECCC, that where thec accused are adjudicated almost wholly by the “victor nations” (noting the Western bent of the court) that, “It is inconceivable that judges schooled in capitalist societies could ever impartially judge.”

As the morning waned, Mr. Koppe yielded the floor to Son Arun, National Counsel for Nuon Chea. In his opening, Mr. Arun said his comments would center on why Nuon Chea joined the revolution, and his contributions to the revolution’s efforts.

An interesting social history

There followed an interesting presentation from Mr. Arun. He shared the personal experiences of Nuon Chea who, as a youth,was “heartbroken” by the oppression of Cambodia by the French. Imbued by a desire to free his people from foreign oppression, he came to believe in the principles of communism as an antidote. He wanted, said Arun, to root out the causes of poverty. Mr. Arun reviewed the history of the emergence of the CPK first as a peaceful socialist movement and, later, as a movement that was forced into armed struggle.

Mr. Arun’s detailed description of the history behind the man, Nuon Chea, extended to a presentation about the American bombings (a time when the CPK had 16,000 forces killed).

“Nuon Chea learned that anyone seeking to elevate the status of the rural poor was subject to swift retaliation,” said Arun. His colleagues believed that “the only path to prosperity lay in an independent Cambodian state. Nuon Chea genuinely believed communism was a path to this freedom.” The defense asserted that this was not a far-fetched or unreasonable idea, that other governments had adopted socialist forms of government, including Nuon Chea’s immediate and powerful neighbors. By bringing communism to Cambodia, the CPK hoped to abolish the existing system and to establish an equitable society, said Arun.

So, he said, determining intent behind CPK policy requires an understanding of things such as the revolutionary language used as a matter of ordinary discourse, and an understanding that the focus was on systems, not individuals, and so on. The goal was to dismantle oppressors and educate the people.

Within the context of this, said Arun, Nuon Chea finds himself perplexed by the prosecution’s efforts. “These efforts confirm NC’s deeply held suspicion that he is being tried not for crimes but for communism, not for conduct but for beliefs,” said Arun, who went on to build a picture where Nuon Chea’s efforts were to liberate his people, feed them, and build a better society.

Arun takes on “gross misrepresentations” by co-prosecutors

After the lunch break on a low-humidity, breezy, sunny day, the court reconvened and Mr. Arun continued his statements. The afternoon topic largely centered on the defense’s detailed analysis of what he referred to as the prosecution’s grossly misrepresentative remarks. For one, he said, Nuon Chea is not a “monster.” Rather, he said, Nuon Chea loves his country and its people. “The accusations are appalling and unbelievable to him, and reflect a misunderstanding of who he is,” said Arun. He quoted Chea as saying, “I have devoted myself to serving my country. I have put my family behind for love of my country.” Mr. Arun maintained that Chea “never wavered from his operatives, never became rich, never acted opportunistically to seek privilege for himself or his family. He lived in the Cambodian jungle for 30 years in service to the principles in which he believed.”

Arun defended Nuon Chea regarding his title of “Brother #2” which Nuon Chea said he never knew of prior to 1975. He did not perceive himself as a “chief ideologue of the CPK” because his role was political education, disseminating political lines through the party, and developing CPK policy as a senior leader of the party. According to Arun, he denied writing a single word of CPK philosophy and he denied being an intellectual. He described Nuon Chea as having a reputation as a negotiator and peace-maker who could bring warring factions together.

Also, Nuon Chea valued his experience learning from the Vietnamese communists, and valued their participation, viewing Vietnamese as comrades-in-arms. He admired their courage & abilities (while also being wary of Vietnam’s intentions and claim of right to Cambodian property). At one time, Nuon Chea was the CPK’s emissary to Hanoi. That said, the threat from Vietnam worsened between 1975 and 1979, and Nuon Chea knew, said Arun, of the threats from the east to the party center. In 1978 there was a plot against Pol Pot, and the perpetrators followed through. The real motivation, according to Nuon Chea, was a combination of control in which the communists in Hanoi turned a disaster into an opportunity. And so, in fact, Nuon Chea’s warning to the standing committee to “stand vigilant” was accurate.

Defense lawyers revisit Nuon Chea’s role in the CPK

Mr. Arun then spent almost ninety minutes detailing Nuon Chea’s role in the CPK to refute the statements of the co-prosecutors. Nuon Chea did, indeed, have a senior position in the CPK, which he does not contest. That role, agreed Nuon Chea, included formulating policies of the CPK. But Arun suggested then that “they know there’s nothing else they can actually prove; the other allegations are in error. The Co-Prosecutors hope to prove that just because Nuon Chea held a position of authority in the CPK that he performed in every aspect of the CPK government.”

Position alone, said Arun, does not prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Nuon Chea “exercised control over cadres at every level in the CPK hierarchy. They [the co-prosecutors] confuse formal structure with practical realities.” The truth, suggested Arun, is that many alleged areas of responsibility for Nuon Chea were outside the scope of his duties as Deputy Secretary.

Arun then reviewed various erroneous claims by the co-prosecutors in great detail. In one case, the evidence was “straw testimony from witnesses who could provide no strong evidence about NC’s role,” he said. He refuted testimony by Iang Sary, saying, “if it were reliable, which it is not, it is wrong. In one testimony with Nuon Chea, Mr. Arun pointed out that “Mr. Nuon Chea says nothing about his own role, but only says criminal activity was punished.”

Arun continued to assert that Nuon Chea was unable to control lower-level cadres. It is because party center failed to adequately control the conduct of lower-level cadres, Mr. Arun reported Mr. Chea of admitting, that he bears moral responsibility for events in DK.

Regarding Nuon Chea’s reported oversight responsibility for the Ministries of Propaganda, Education, and Social Affairs, the first two, said Mr. Arun, were true, but not the third. With a primary responsibility in the CPK for propaganda and education, Nuon Chea did make decisions about content of materials, but denied being Minister of Propaganda. Mr. Arun refuted the co-prosecutors’ assertion of Nuon Chea’s role in the Ministry of Social Affairs, saying they relied on testimony by “three wholly unreliable witnesses, none of which comes close to establishing beyond a reasonable doubt he had any role in this regards.”

Regarding Nuon Chea’s role in the People’s Representative assembly, Mr. Arun called to task the translator’s choice of words in the English translation. He asserted that the Khmer translation means something different and did not say the assembly was “worthless.”

Regarding Nuon Chea’s role as Acting Prime Minister of DK in 1976-1977, Mr. Arun said that Nuon Chea has consistently denied it and is not familiar with any document purporting to describe him as acting Prime Minister, and said that anyhow, “the issue is of no significance to this case.”

Regarding the co-prosecutors’ assertion that Nuon Chea was in charge of the affairs of military and security issues, Mr. Arun took to task the co-prosecutors’ claim that Nuon Chea’s responsibility is so clearly established by the evidence that his denial is “contrived.” Said Mr. Arun, “This is pure posturing, a blatant effort to misrepresent the evidence. In reality there is almost no evidence that Nuon Chea had a role in military affairs.” He then showed other testimony to demonstrate that his client was not part of the military committee.

Mr. Arun spent time next discussing a discrepancy in the matter of telegrams. Although, he said, the co-prosecutors state repeatedly that these telegrams are very significant in showing that other members knew to communicate with Nuon Chea about military affairs, in fact they found only six telegrams in the years of DK that were sent to Nuon Chea regarding military affairs. With some detail, Mr. Arun showed how, in his view, these telegrams are significant only because they are nearly the only ones that exist and that all six were from the same specific military officer in region 164, and all were sent in Oct 1976 with generally the same subject matter. His conclusion: “They signify nothing in terms of Nuon Chea’s general responsibilities, and the co-prosecutors’ continued reliance on them shows that no other evidence exists.”

In one single meeting of the Standing Committee where Nuon Chea makes commentary about military affairs (26 March, 1976), Arun cautioned the chamber to notice that careful review of this document shows that, although Nuon Chea had no substantive role in military affairs, Pol Pot was absent that day, and in his absence, NC’s principal instruction was “to keep implementing.”

Next, Mr. Arun addressed the evidence regarding when Nuon Chea presided over a restructuring of DK–a seminal moment in the CPK. His presence, asserts Arun, was ceremonial, as it tended to be at military gatherings chaired by others.

Another comment by Arun looked at the way the co-prosecutors tried to show Nuon Chea role as “head of political leadership of the army,” and yet, asserts Arun, the document in question proves Nuon Chea’s position that he was a civilian leader with no role in military affairs. Any “military” role was to educate soldiers, just as he educated civilians.

S-21 confessions, other official documents, and Nuon Chea’s handling of them

At this point in the litany, chamber president Nonn asked Mr. Arun if, by chance, it was a good time to break, but Mr. Arun said he had just 20 pages to go, so the proceedings continued working through a considerable volume of detail, complete with page and paragraph references. This final section of the defense statements centered on S-21 and confessions to which Nuon Chea had access. According to Mr. Arun,of the 4,189 confessions found at S-21, Nuon Chea was sent just over 1/2 of 1 % of the confessions in existence (25 confessions). If the prosecution wants to claim that Nuon Chea had a role at S-21, asked Mr. Arun, it seemed logical that many confessions would have been sent to Nuon Chea and there would be better proof that he saw them, but, said Mr. Arun, that proof does not exist.

There followed the relief of a mid-afternoon break for twenty minutes. Afterwards, Mr. Arun continued delving into the matter of Nuon Chea’s handling of documents in his role as Deputy Secretary. In essence, Mr. Arun asked the court to consider the handling of documents by anyone in a senior leadership position as evidence that that person is also in charge of the departments sending reports. Just because a department sends documents does not mean the person in charge always sees those documents. Nuon Chea, said Mr. Arun, “was not in charge of every entity that sent them. Would the vice-president of the United States be in charge of every department that forwards memorandum?”

Mr. Arun then made the observation that Nuon Chea has answered some of these questions. He used a small number of confessions for the purpose of education. Now, 35 years later, he does not remember exactly which ones, but that explains why some small sample of the confessions may have been sent to him. In addition, 13 of the 25 confessions concerned a single military unit and were more likely sent to him not because they happened to come from S-21 but because they had to do with a military unit that Nuon Chea had some interest in. There is no proof, as the co-prosecutors say, that it is because he had a part in the purging of that unit. “To be absolutely clear,” said Mr. Arun, “Nuon Chea does not concede his role in any military purges. But we bring these to your attention that even the prosecution cannot come up with a consistent explanation of why these document were sent to NC.” No one knows. Overall, though, it is “telling of the poor quality of the evidence against Nuon Chea.”

Evidence is clear according to defense that Nuon Chea had no role at S-21

Mr. Arun then turned to clear evidence that Nuon Chea had no role at S-21 despite the assertions of the prosecution. He reminded the court how the co-prosecution said Nuon Chea proclaimed that role to Sambath. However, said Mr. Arun, not once in more than 1,000 hours of videotaping did Nuon Chea say that as he launched into details supporting his assertion. This commentary also included the opinion of the defense that the testimony by Duch from case 01 is simply recycled information with no relevance or probative value. And yet, “having found no evidence of Nuon Chea’s role at S-21, the co-prosecutors tried to make it happen circumstantially.” He then gave the chamber an exhaustive list of inconsistencies to the only evidence remaining that Nuon Chea had a role in S-21 and explored the various reasons why the testimony is unacceptable for use by the chamber.

No outright dispute with Nuon Chea monitoring autonomous zones and sectors

Mr. Arun went to the next topic, of Nuon Chea’s role in monitoring the autonomous zones and sectors, saying that Nuon Chea does not dispute this assertion outright. Standing Committee policies were implemented by zone-level officers, and the Standing Committee monitored the extent to which high-level objectives were being met. “However, it is not correct he directed implementation of those policies,” said Arun. “His ability to monitor zone-level implementation was based on the cooperation of zone officers.” His job was holding meetings with zone and sector leaders in Phnom Penh, receiving reports, and making trips to the provinces.

Then Mr. Arun asserted that, regarding reports and telegrams, Nuon Chea’s receipt of telegrams is not probative. He was only told what they wanted him to know. “In fact, the evidence conveyed was systematically inaccurate,” said Mr. Arun, since it was typical of cadres to overstate good results and downplay negative or difficult situations. Also, Nuon Chea almost never responded to these telegrams, and thus did not supervise in any substantive way, because he did not respond to those communications. Any assertions otherwise by the co-prosecutors, said Mr. Arun, are incorrect.

Likewise, regarding the issue of trips to the provinces (as the co-prosecutors suggested to be a method for supervision of the zones), there is nothing of value in the evidence. Nuon Chea had no supervision over the zones, only over zone secretaries. There is no evidence connecting Nuon Chea with arrests that followed his speeches; Mr. Arun pointed out that the co-prosecutors were unable to find one example in which an arrest followed a speech by Nuon Chea.

At this point, since the clock was nearly on the hour of 4:00 p.m., the chamber adjourned. Closing statements for the defense team of Nuon Chea will resume Thursday, 22 October, 2013 at 9:00 am, since a national holiday will keep the court closed on Wednesday.