Defense for Khieu Samphan Keeps the Court’s Attention

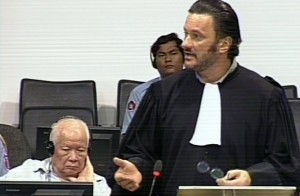

Closing statements for Khieu Samphan started with a civil tone today, but by 10:30 a.m. had devolved into a sizzling diatribe by International Co-Defense Lawyer, Arthur Vercken. Perhaps there was good reason the parking lot (which is still half-flooded from rains earlier in the week) was crowded with buses, their passengers lined up to pass security and gain a seat in today’s gallery before the 9:00 a.m. start.

Mr. Vercken offered a mild opening salvo to the chamber as he explained how his team had worked to develop substantive arguments in the closing brief “within the limit of 125 pages you imposed upon us.” Then he complimented his counterparts on the defense team for Nuon Chea for two excellent days of remarks. Saying that to revisit those points seemed unnecessary, and so, “we would like you to consider that everything they stated with much talent is accepted and supported by us in the Khieu Samphan defense,” he said.

Mr. Vercken offered a mild opening salvo to the chamber as he explained how his team had worked to develop substantive arguments in the closing brief “within the limit of 125 pages you imposed upon us.” Then he complimented his counterparts on the defense team for Nuon Chea for two excellent days of remarks. Saying that to revisit those points seemed unnecessary, and so, “we would like you to consider that everything they stated with much talent is accepted and supported by us in the Khieu Samphan defense,” he said.

For the first part of the day, Mr. Vercken said he would begin with questions regarding the scope of the trial, followed by an examination of some issues regarding the trial evidence. His International Co-Lawyer Anta Guisse would then speak, followed by their colleague, National Co-Lawyer Kong Sam Onn to finish this first day

Three key dates highlighted

In order for the public to understand the manner in which the prosecution has changed their legal and factual argumentation in their closing brief and oral statements (thus affecting public perception of the scope of the trial, according to Mr. Vercken), he reviewed three key dates:

- September, 15, 2010, when the investigating judges issued the closing order covering the totality of the facts between April 17, 1975 and January 6, 1979. This order mentioned many alleged crimes committed under the aegis of five policies of Democratic Kampuchea (DK): 1) three major population movements, 2) implementation and operation of cooperatives and worksites, 3) re-education of “new” elements and the slaughter of enemies both within and outside the ranks of the party, 4) targeting of former Khmer Republic (also known as Lon Nol) soldiers and officials, intellectuals, and also Cham, Buddhists and Vietnamese, and 5) the regulation of marriage;

- September 22, 2011 (the severance order, announced prior to the start of the trial). Mr. Vercken explained how, given the many crimes alleged, the chamber decided to select certain facts for consideration in the first initial trial. (The other facts were to be tried later on in further trials.) The facts chosen for the severance order were limited to two of the three population movements;

- On October 8, 2012 (decision E163/5). Although, he pointed out, the trial had started 11 months and 13 days earlier, the chamber decided to extend the severance order announced on September 22, 2011 by adding the events of Toul Po Chrey in the days following the evacuation of Phnom Penh in April, 1975. On that day, the chamber passed along a document showing a definite list of the framework of the current trial. As the “founding document of today’s trial,” said Mr. Vercken, facts not covered in the severance order cannot be tried, “and were not the object of the two years of proceedings that have just passed.”

Only a very certain few could be authorized to step outside the scope of the trial as defined, reviewed Mr. Vercken, just civil parties, when they spoke about their suffering, and very elderly witnesses. During the two years of hearings, each time a witness “dared to bring up facts outside of the two population movements and, as of October 2012 when you added Tuol Po Chrey, facts outside this predefined scope, the chamber interrupted the witnesses and lawyers” to stop their testimony.

Expert witnesses, David Chandler and Philip Short, too, were allowed to bring up facts going beyond the scope as defined, or even the policies that encompassed them. Thus, said Mr. Vercken, “the scope of the trial varies in this way.” He said that the Khieu Samphan defense chose not to lodge an appeal on the decisions to sever the trial or to amend the scope 11 months after starting it. “We believe that the rules were stable and would be respected and that the acquittal would be quicker, let’s say things frankly,” he said.

Mr. Vercken continued his edification of listeners, explaining that lawyers are legally free to characterize the facts, as long as the defense also has the possibility of re-characterizing the facts. “I’m speaking about the way we dress up a fact,” he said, “the category in which we place this fact, not the fact itself. A trial is first of all the fact. The fact is the root of the story, the action, the founding event, whereas the legal characterization may fluctuate until the end as long as the accused has had the possibility of defending himself. The fact that is tried cannot change, unless you violate all of the principles of a fair trial.”

A detailed review of the list of facts being tried

With that made clear, Mr. Vercken walked the chamber through the definite list of the facts for this case as provided on October 8, 2012. He summarized the seven major parts of the document which constituted four pages of information. He spoke in painstaking and very specific detail about:

- Specific factual presentation. “It’s clear,” he said. “There is no room for the slightest doubt;”

- Facts related to the alleged crimes;

- The role of the accused. “This is clear, isn’t it?” he said rhetorically;

- Legal findings relative to alleged crimes. “Things are very clear, aren’t they? It is written in black & white,” he said;

- Modes of responsibility. “Once again everything appeared to be clear to me,” he said again;

Again and again, Mr. Vercken emphasized in a rushed, urgent tone how the examination of the fact would be completely limited to very specific events (population movement, phases 1 and 2, and the events at Tuol Po Chrey in April, 1975) and very specific groups of people (soldiers and officials of the Khmer Republic). At the end, he said it again: “This reading shows that it is unquestionable that whenever we have to talk about the facts, the modes of liability, you are limited your jurisdiction to population movement, phases 1 and 2, and the events at Tuol Po Chrey in April, 1975.”

At this point, Mr. Vercken went into considerable detail regarding the facts of the case, part by part. He noted, with regard to the evacuation of Phnom Penh, that the start date of April, 17, 1975, is well-known but not the finish. Likewise, the dates surrounding the population movement, phase 2, are difficult to determine specifically (approximately September, 1975, but for how long?), as are dates for Tuol Po Chrey. In addition, the numbers of victims for all the events are unclear. “All that is very vague,” he confirms, raising the specter of conjecture, complicating the concept of proof regarding details of the events.

Yet, Mr. Vercken pointed out, “there are two key areas of the trial where the prosecution has asked the chamber to rely on facts that are outside the scope of the trial to find Khieu Samphan guilty and sentence him to life imprisonment.” They do so regarding their characterization of crimes against humanity and in their definition of the common purpose of the joint criminal enterprise (JCE). For non-jurists listening in the gallery, “let me point out that a crime against humanity is a common-law crime (also known as an underlying crime) with the specificity of having to be committed in a specific context. Before this chamber, in order for us to say that this underlying crime is a crime against humanity, the basic crime must have been committed as part of a systematic or widespread attack against a civilian population and on discriminatory grounds.”

Mr. Vercken then compared the approximate numbers of victims cited for the two population movements and Tuol Po Chrey (200 to 5,000) and what the prosecution claimed (hundreds of thousands tortured and 800,000 to 1.3 million dead), and concluded, “We are not talking about the same trial.”

Likewise, he accused the prosecution of extending the range of event dates to three years and eight months, not the much narrower date margins the defense recognizes. In addition, he pointed out that the prosecution tried to include populations excluded from the facts (Cham, Vietnamese nationals, intellectuals, and others) in their argument.

Next, Mr. Vercken turned his attention on the reasoning of the prosecutors regarding JCE. “For non-jurists listening,” he said, referring particularly to law students in the gallery, “JCE is the fact that at least two people agree with the view of committing one of the crimes before this tribunal. So JCE is not a crime, it is the form of committing the crime.” Mr. Vercken then went into deep detail about the relationship of this point with the charge of “enslavement” raised by the prosecution, and concluding that their argument exceeded the severance order. “The prosecutors cannot prove what they are asserting,” he said.

He asked, what are the prosecutors really talking about? At this point, warmed to his subject, Mr. Vercken forgot himself and began to reel off rhetorical questions at a pace that moved chamber president Nonn to step in to ask him to please slow down, which he did (momentarily).

Accelerating to nearly the same rate of speech, Mr., Vercken warmed again to his topic, which turned to the scope of this trial, given the severance order. The charge of enslavement as a crime against humanity is expressly excluded, Prosecution use of victim numbers on the order of 800,000 to 1.3 million is not allowed when the facts of the case have victim numbers ranging from 200 to 5,000 people. The prosecution’s date range of three years and eight months is not allowed, if the facts recognizes them as ranging most broadly from April 1975 to December, 1976 (one year, eight months).

Is the prosecution actually tourists dressed in purple robes, wonders Vercken

“The rules regarding referral of cases before international criminal tribunals are such that 90% of what you have heard the prosecutor plead over the past few days is off-topic,” said Mr. Vercken. “These rules are taught in first year programs in law faculties. It is basic. It is elementary. It is not possible to have a fair trial unless these rules are abided by.”

At this point, Mr. Vercken began to turn his commentary toward the bench, wondering if those setting up the prosecution teams somehow “unwittingly” hired a gang of tourists who “would want to make a few dollars by donning purple robes”?

He continued: “Most of you are from the Anglo-Saxon system so you are lawyers disguised as prosecutors, so I can suppose you are ready to tell any story in any manner to win your case. Unfortunately that is the opinion we, the defense lawyers, are accustomed to having. Even though your first commander defected recently [referring to the recent resignation of a member of the prosecution team], you believe you are on a commando mission, a mission which consists in obtaining a convictionat all costs.”

He continued, saying, “You are convinced that your mission is more important than the rules of law and procedure. You are wrong, counsel for the prosecution…”

Whereupon chamber president Nonn interrupted Mr. Vercken and asked him please to “use your words professionally and abide bythe Code of Conduct for Counsel. The chamber hoped your statements will not have a negative impact on other parties, so please do not direct your closing statement to any particular individual.”

Only slightly chastened, Mr. Vercken immediately continued in the same vein with words worth quoting to demonstrate the tenor of the morning:

“Under the cover of a commando mission you are taking the risk of ridiculing a legal system that is already quite weak, of drowning the only true mission entrusted by the United Nations, to participate in the establishment of a strong and equitable justice. You are taking the risk of violating the public interest you are supposed to defend and represent when you bring up facts that were never the object of this trial, and whose legal characterization is also impossible because the facts that correspond have been expressly cast aside without re-discussing their inclusion. You are taking the risk of giving a very poor example in Cambodia and to the rest of the world that has commissioned you to participate in this work of justice no matter the outcome. If this trial is only focused on a sentence, then we should stop it immediately. It will be of no use, no matter the outcome.”

Accounts of procedural frustrations continue

In his next point, Mr. Vercken pointed out a bit of procedural frustration (not for the only time) in which his office discovered a submission by the prosecution that the chamber “did not deem necessary to give to us” and which was only discovered by accident. At any rate, discovery of the document raised in Mr. Vercken “a brief moment of hope” because in the request the prosecution begged the judges “not to draw conclusions from all of the facts that are not part of the crimes selected for this current trial” at least partly because the defense “has not had the opportunity of confronting and cross-examining the slightest witness of these facts.” After thanking the prosecution for this glimmer of hope, Mr. Vercken immediately also noted that what was at issue was inadmissible factual and legal elements, “but at least there was some kind of nice appearance.” There followed additional insults including that the chamber has “reached the bottom” and is hearing “phony rhetoric” such as in the manner of Co-Lead Prosecutor Leang’s request for a life sentence for his client on Monday.

At this point, Mr. Vercken’s comments mushroomed to overarching concerns of human society, as follows: When entrusted with the care of trying another human being for grave crimes, “societies generally take a bit of caution” regarding choosing judges who are knowledgeable and ethical, who work in teams “as a rampart to the excessive power of one.” Such judges, said Mr. Vercken, regard rules as their “best allies” that allow the judiciary “to achieve the enormous task that consists in trying alleged events.” Rules are strong and are not meant to be modified by the judges.

But, said Mr. Vercken, the prosecution’s request for a life sentence is “like a coup d’état against the five of you” (referring to the panel of judges) in the regard that the rules imposed should be ignored in this case, that they are not that important in the end. “The objective of the prosecutors is to condition you, to relieve guilt from you in advance, and ask you in a certain way to violate your own oaths. Don’t be afraid; they [the defendants] are already guilty so no one will criticize you for tampering with the law.”

Strong laws are respected, asserted Mr. Vercken. Laws that are violated erode society. Can national reconciliation come at the price of ignoring the rules of law, he asked. He listed inadmissible evidence and other irregularities to the trial at hand that threaten the tribunal’s integrity.

Mr. Vercken’s rapid-fire litany

Mr. Vercken then launched into a rapid-fire litany of information ranging from a discussion of enslavement (although it isn’t covered in this trial) to the culpability of Khieu Samphan, to the American pilots dropping bombs and agent orange, who, like Khieu Samphan, did not look into the eyes of their victims, either.

But the real point, asserted Mr. Vercken is that “it is not to you that the prosecutor spoke these last few days. They spoke to a popular jury they believe overrules you. They are banking on the horrible fact that we call public opinion. The entire world has become a popular jury instead of you, your honors, and the prosecutors spoke to them in these last days. They did so because they are afraid that there still exists a hope that you do your job as judges. There is always a hope, whereas public opinion is easier to shock, and remains insensitive to issues of legal procedure.”

But the real point, asserted Mr. Vercken is that “it is not to you that the prosecutor spoke these last few days. They spoke to a popular jury they believe overrules you. They are banking on the horrible fact that we call public opinion. The entire world has become a popular jury instead of you, your honors, and the prosecutors spoke to them in these last days. They did so because they are afraid that there still exists a hope that you do your job as judges. There is always a hope, whereas public opinion is easier to shock, and remains insensitive to issues of legal procedure.”

Mr. Vercken then listed numerous complaints regarding his client’s lack of access to documentary evidence and other legal safeguards to a fair trial, and “how the world does not care about the conditions in which this trial is taking place.”

It was when Mr. Vercken claimed with heightened vocal pace and volume that “this is a theater and this is a show” that chamber president Nonn for the second time spoke to the defendant’s co-lawyer and reminded him not to direct his statements to any particular individual. His words turned Mr. Vercken’s strategy back upon himself: “What you have raised is not involved in the facts adjudicated in this court, so make your statement respectful to the chamber and to the parties and the public… Try not to use this time to attack other people or this chamber or this court.”

To which Mr. Vercken said, “Well, probably we don’t have the same concept of what a final statement is, Mr. President. I don’t believe I offended anyone here by defending my client before you, nor have I insulted anyone. Lawyers are free. This is a moment of freedom, a moment where the defense may express itself without being limited or threatened.”

After some other statements, Mr. Vercken said, “The truth is, Mr. President, that at the end of this trial, we believe that either you will abide by the law and acquit our client, or, you will sentence him. We believe [that would be] a violation of the basic premises of criminal law.”

The (possible) future for Cambodian justice in the wake of these trials

There followed some commentary about the potential for Cambodian judges to do just as good a job as western-trained lawyers. To the Cambodian judges, he said, “this is your country. Your justice. Your reputation at stake. One day, the authoritarian and corrupt regime in this country will have to accept its defeat. A new era might begin, and we also have to prepare ourselves for this era. And you, Cambodian magistrates, may be among those who will start this revolution….”

At which point chamber president Nonn again interrupted the speaker, saying, “Your statement is out of the scope of this trial.”

Still Mr. Vercken spoke back: “I’m well aware of this.” He went ahead and argued the point that if the prosecution has been allowed to argue outside the scope of the trial so, too, should he be. “What sort of justice authorizes the prosecutors to say any old thing and the defenders from condemning this situation? This is the aim of my statement.”

With a few more remarks, Mr. Vercken yielded the floor in honor of the mid-morning break and, if the reaction in the media room was any indication, most observers leaned back and took a deep breath.

Upon returning, chamber president Nonn reminded Mr. Vercken that the defense is limited to just two days to make its closing statements. He also received clarification from Mr. Vercken that Khieu Samphan will address the chamber not today but next week, during the time allotted for his remarks.

Mr. Vercken then began his statements regarding issues surrounding the evidence in this case. He referred to the statement by the defense for Nuon Chea and echoed their assertion that one look at the prosecution’s justifications and this trial could have been concluded for just a few thousand dollars. He demonstrated by showing two videotapes of Prince Sihanouk in New York City, the first in October, 1975 (six months after the evacuation of Phnom Penh) and the other in February, 1979, shortly after the demise of DK. The intention, asserted Mr. Vercken, was to show the different things evidence can show; the videos include Prince Sihanouk claiming that when he saw Cambodian cooperatives, they were filled with people who did not seem unhappy or famished.

Mr. Vercken then began his statements regarding issues surrounding the evidence in this case. He referred to the statement by the defense for Nuon Chea and echoed their assertion that one look at the prosecution’s justifications and this trial could have been concluded for just a few thousand dollars. He demonstrated by showing two videotapes of Prince Sihanouk in New York City, the first in October, 1975 (six months after the evacuation of Phnom Penh) and the other in February, 1979, shortly after the demise of DK. The intention, asserted Mr. Vercken, was to show the different things evidence can show; the videos include Prince Sihanouk claiming that when he saw Cambodian cooperatives, they were filled with people who did not seem unhappy or famished.

Other evidence held up by Mr. Vercken was intended to demonstrate the frequent misuse or distortion of evidence by the prosecution. Part of the problem, he declared, could be the age of the testimony, reaching back as it does more than 38 years.

Mr. Vercken paid special heed to the lack of original documents, stating that in over two years there had been only two original documents. Everything else has been a digital copy or photocopy. As such, he worried, it is only a virtual file existing only in its digital form. He wondered about authenticity, chain of custody, and ease of access to the tens of thousands of items of evidence underlying these trials. He denied ever seeing the proper case file, because it holds only scans or partial copies.

Regarding access, Mr. Vercken cited Article 86 of the internal rules, which says those central to the case can obtain these things, yet documents often cannot be found, despite an award in the ECCC lobby declaring its great technical innovation.

Mr. Vercken cited the examples given by the Nuon Chea defense team regarding the low probative value of much of the evidence because of lack of cross-examination. He referred to a limited ability for people, especially his client, to read documents in their native languages. He referred to the refusal by the head of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) to reveal where many of the original documents it has on file are being kept. “Why should we believe him when he asserts he has originals?” asked Mr. Vercken. He expressed a sense of entitlement to be concerned about the probative value of evidence, chain of custody, secret documents and everything else he needed to use to defend his client.

Mr. Vercken concluded his statements by saying, “A tribunal is not there to write stories. A tribunal does not have a historical function. A tribunal is not there to foster national reconciliation above all. A tribunal is there to do justice according to the rules of criminal law on the basis of irrefutable evidence and that is all. That would already be a lot.”

At this point, Mr. Vercken yielded the floor to his colleague, International Co-Lawyer for the Khieu Samphan Defense, Anta Guisse.

Anta Guisse speaks of conviction—or actual justice

Guisse wasted no time getting to the point. “Convict them quickly,” she began. “Convict them quickly, before they die, Mr. President.”

With a certain calm eloquence, Ms. Guisse spoke how the public and the donors would all prefer for this case to “ply its course.” She said that everyone knows that all that is expected is a verdict of guilty. “There is no one in this courtroom who is expecting any other judgment than conviction.”

But, she said, it would only be a symbolic thing, something to “lend the impression we have achieved our objective in the eyes of history.”

She named the international court as a paradox in which rights and human rights “are put to the fore, but in reality, what we judge is not the people and their responsibility for their actions but the symbol. If we are to try history we have to try history in its entirety. And since the historical context is important, that is where we will start.”

She named the international court as a paradox in which rights and human rights “are put to the fore, but in reality, what we judge is not the people and their responsibility for their actions but the symbol. If we are to try history we have to try history in its entirety. And since the historical context is important, that is where we will start.”

Ms. Guisse pointed out that being a defense lawyer means thinking about things differently, just as judges have to learn to think differently. “We think someone should pay the price, but how do you go about it?” she asked. “We must go beyond preconceived judgments. Everyone has biases, but what has to happen here is that people need to set aside their biases and preconceived judgments in order to really see what both sides have to say.

She then repeated her opening line: “convict them quickly, before they die.” But on what basis? She referred to many historical underpinnings, such as the starving Cambodian people, victims of the Cold War and American bombings, and years of agricultural destruction. She spoke of ideological struggles so far in the past from 2013 as to make them feel too distant; things have changed significantly. But in the 1960s, and 1970s, the struggle for independence gripped many nations.

“Recall,” she said, “that the issue before us is, do we want to try a man? Or do we want to try history?” She asserted that to judge a man means also judging a political system, which means examining everything, especially history, everything that is part of the reality of a case at hand.

A review of the Cambodia of the 1970

Ms. Guisse brought to vivid awareness the scene in Cambodia in April, 1975: the destroyed, bankrupt country. She asked why, then, did the evacuation really happen? She spoke of the need for food production, the military needs, the fear of more bombs, dirty bombs carrying napalm and Agent Orange. Some people understood the need for temporary evacuations, she said, citing various evidence that supports the premise that the actions were not punitive measures taken against urban dwellers as alleged. If the population of Phnom Penh went from 500,000 in 1971 to 2.3 million by 1976, and American bombing commenced in between, and half of the increase consisted of peasants who had fled their land because of those bombings, it says something. She said refugees were fleeing also from the fighting, which was not just by the Khmer Rouge.

There is a Khmer saying, she said, that “when elephants fight it is the ants who pay the price.” Shortages of food and housing in Phnom Penh stemmed from all these reasons and added to malnutrition and other health problems, and Guisse cited extensive supporting evidence to that effect. “The events of 1975 did not spring from nothing,” she said. “We cannot isolate that period without talking about previous periods.”

And American aid for Lon Nol came at a time when the Cold War was in full swing and aid came with strings attached. “The truth is multi-faceted,” she asserted. Can we sweep these aside economic reasons for the evacuation? Or were the CPK and KR just trying to enslave the people? What transpires in the evidence is that the economic situation in April 1975 was disastrous.

At this point, the proceedings adjourned for the lunch recess until 1:30 p.m. Afterwards, Ms. Guisse continued her appraisal of the reality of 1975. She reiterated the effects of five years of warfare in rural Cambodia and the terrible devastation it left in its wake, citing American bombing levels that were three times higher than what was dropped in Japan (including the atomic bombs) in World War II. Seventy-five percent of livestock was destroyed, she said, leaving it necessary for undernourished people to use their own bodies to pull their plows. Of arable land, 80 percent was abandoned. Rice production in 1974 was 650,000 tons, compared with 3.6 million annual tons before the war. There were, she concluded, clear economic reasons for the 1975 evacuation.

“I am troubled in the closing order,” said Guisse, “where the investigators are not afraid to say the food penury was caused by self-imposed conditions. Seriously?”

Guisse alleges penury, not punishment, as the underlying factor in the second population

She turned her attention to the people in charge of implementation of the evacuation, and how her colleagues on the Nuon Chea defense team did well in reminding the court about this. She reiterated the testimony that the evacuation took place under the responsibility of the zone armies, which were never unified. She pointed out, too, how treatment of the population varied. For example, one set of evidence showed that soldiers of eastern zone were said to be more lenient than the western zones. Much depended on the lower ranking cadres, she said.

Of the evidence surrounding the second population movement, none, she pointed out, mentions Khieu Samphan’s involvement. In fact, of the two items of evidence she held up, Khieu Samphan was abroad when one of them was written.

Ms. Guisse revisited the concept of context in her comments on reasons for the second population movement. In August, 1975, she said, there was still penury in the country, so the justification for this population movement is economic, not criminal. Evidence shows a perception that the situation was seen as a chance to improve the food supplies. Moving that many people meant the need to build dwellings, and this the need for brick making, for example. There was a need for workers to be located where land was more fertile and supplies were available, and so they were sent to a region always considered richer, a place Stephen Heder describes as the “rice basket” of Cambodia. In that region, too, she said, there was less fighting. The overall situation, she concluded, “was better compared with the disastrous situation prevailing in the rest of Cambodia.”

“When you look at the reasons behind which the decision were taken, and we’re looking at intent and not whether or not they were successful, the aim was not to punish the city dwellers or new people,” she asserted. “The aim at that point was to try to find a solution to the poisonous, disastrous situation that they had inherited.” She agreed that there was an ideological component to the process of creating the collectives, “as most economic stances are that most states take,” she said. But, she asked, was there really a choice? “What other source of creating income was there aside from agricultural, then? None.”

So, in conclusion to her point, she said, “The circumstances preexisted the KR. We cannot support the prosecutors’ idea that this policy was only something used against the population. We are not saying the population did not suffer. Of course we understand this, but the abuse and targeted abuse against the new people was not going on.”

Ms. Guisse then turned her attention to the subject of who was actually in charge. She referred to the prosecution’s frequent references to warlords. The Nuon Chea defense covered this matter very well by explaining the power was held by those leading the zones, she said. She referred to the expert witness testimony of Philip Short, who said in his book about Pol Pot book that the reality in DK was contrary to the communist system in which decisions were taken in a monolithic manner. When a party center decision was made, he said in May, 2013, the line of the center was given to the zone chiefs, who interpreted it as they wished. “There were considerable variations and difficulty harmonizing things nationwide,” he indicated, which Guisse contended is a far cry from a center that controlled everything.

Guisse went on to hold to the light similar, corroborating evidence of her assertion that the party center did not control everything. “It is important to go beyond the investigating judges who may not seek exculpatory evidence,” she asserted, because “when this isn’t happening there is a problem in the administration of justice.” Even if Khieu Samphan ordered distribution of supplies, there simply was not enough of supplies and clothing. The real problem, she said, was the incompetence of the local cadre.

“We should not keep harping on this view that central had authority over everything,” she said, when there is abundant evidence showing how powerful those in power in the zones were.

And as for intent, she went on, the “closing order states that the main objective apart from the needs for manpower was to deprive urban dwellers and to transform them to peasants. This is another myth.” Citing how the evidence “does not tally with the situation on the ground.” She once again reviewed causes underlying the state of things in 1975 to 1979.

Perhaps poor leadership was the real problem

If you want to go to the heart of the trial, what was the policy of the party center?” she said, saying that the goals of the KR were not negative in themselves. It was the system that didn’t function, particularly with respect to food as controlled by the local cadre. The Standing Committee knew people needed to be properly fed, she indicated, quoting Pol Pot himself as saying so. “The situation wasn’t functioning properly. The cadres were overwhelmed. But the objective was not to cause suffering, which is important if we are going to talk about joint criminal enterprises.” Meeting the needs of the evacuees and integrating new people with the old are frequent topics in the record, she said, pointing out numerous examples.

“A slew of statements made before your chamber.”

Meanwhile, Ms. Guisse suggested that it is possible to reflect on the notion that the Khmer Rouge were utopic in their views, that perhaps they did not fully understand human nature. But she bridled at the suggestion that the goal was to discriminate against the new people. Certainly, some cadres who did not do their work were criticized. She referred to the testimony of some civil parties that they were ill-treated, but “what we are saying if they were ill-treated is not that it was because of instructions from the center or from Phnom Penh, or part of a JCE. To crush the Cambodian people was not the objective,” said Guisse. Overall, “they wanted to live as revolutionaries and take care of the people.”

“Is it an excuse or an explanation?” asked Ms. Guisse. “Your chamber did not allow me to explore this with Philip Short, but the need for an explanation still remains. Maybe it was a utopia, an extreme form of idealism, maybe something that did not work, but was the aim to discriminate against new people, to create the slave state? Or are we not just dealing with leaders unable to manage the situation?”

Ms. Guisse ended by returning to the baseline that the court is in charge of trying people, not a political system. As such, she then turned the podium to her colleague, National Co-Lawyer for Khieu Samphan, Kong Sam Onn to speak about Khieu Samphan’s background, since, she said, this has never yet been adequately covered in this trial.

National Co-Lawyer for Khieu Samphan, Kong Sam Onn,

Mr. Sam Onn began with a commentary about Khieu Samphan’s various positions and roles. This is relevant, he said, to refute anything the prosecution might use to show beyond a reasonable doubt that Khieu Samphan’s acts can legally be tied to the JCE, or to support the claim of aiding and abetting certain criminal acts, as well as that the commission of crimes falling under the jurisdiction of the ECCC. “We are dealing with a criminal matter,” said Mr. Sam Onn. “Does Khieu Samphan fit?”

He went on to assert that Khieu Samphan “cannot be responsible for all the acts that occurred during the DK regime.” He then listed numerous examples from the 20 month trial showing his personal character to be honest, a seasoned intellectual, gentle, patient, modest, non-discriminatory, non-argumentative, humble, and just. Even his wife, So Socheat, testified to his character, saying he didn’t seek rank, fame, or authority and that “he even washed nappies.” After 30 years of marriage, she said, “I still trust my husband.”

Mr. Sam Onn continued demonstrating testimony describing Khieu Samphan as loving, that he was very popular and respected, and was not greedy for power or authority or material possessions. Witnesses described him as good, and always deeply loyal to the nation. The word “clean” (meaning non-corrupt) continually appeared, and one anecdote included how he returned a Mercedes “given” to him by a businessman. He was said to be even-tempered, analytical, and considerate. He preferred a simple life, and even as recently as 2005 lived in a home without running water, according to one witness. He was loved and respected, asserted Mr. Sam Onn.

What Khieu Samphan wanted most of all, said Mr. Sam Onn, was to promote the people as the nation of Cambodia.

Mr. Sam Onn’s presentation was an exhaustive summary of Khieu Samphan’s resume. As an aside, while his counsel spoke, the defendant, Khieu Samphan was visible on the live audiovisual feed from the courtroom, head in hand. As the presentation droned on for some time, even the defendant seemed to sink lower and lower in his chair. The summary included Khieu Samphan’s academic background, his introduction to and embrace of communist ideology, his on-going interest in finding economic and social improvement for the people. His interest in helping his country achieve independence from France. He founded independence newspapers critical of the regime under Prince Sihanouk, and was for a time imprisoned without trial, then constantly monitored by police, the defense stated.

Mr. Sam Onn’s presentation was an exhaustive summary of Khieu Samphan’s resume. As an aside, while his counsel spoke, the defendant, Khieu Samphan was visible on the live audiovisual feed from the courtroom, head in hand. As the presentation droned on for some time, even the defendant seemed to sink lower and lower in his chair. The summary included Khieu Samphan’s academic background, his introduction to and embrace of communist ideology, his on-going interest in finding economic and social improvement for the people. His interest in helping his country achieve independence from France. He founded independence newspapers critical of the regime under Prince Sihanouk, and was for a time imprisoned without trial, then constantly monitored by police, the defense stated.

“And still he tried to transform Cambodia by peaceful means,” asserted Mr. Sam Onn. “He still did not like any corrupt matters” and remained very “clean.” This character trait was nationally popular, said Mr. Sam Onn, such that Khieu Samphan was nicknamed “Mr. Clean.”

As described by David Chandler, who worked in Cambodia from 1960 to 1962 at the American embassy during testimony in July, 2012, “Prince Sihanouk was afraid of him because he was clean and dignified and could be an important figure in the society, and that made him very concerned.”

After the Peasant Rebellion in 1967, Prince Sihanouk accused Khieu Samphan of taking part and called for his arrest and even put out a reward. The defendant fled from Phnom Penh to Kampot, which led to his history with and within the CPK, a history initially marred by his status as an educated man. In fact, Khieu Samphan could not meet the ten criteria necessary to be an active member of CPK. He stayed solitary in the forest for seven years, mingling with the farmers and living a quiet life until 1969 when he was admitted as a party member.

As the afternoon wound down, Mr. Sam Onn began to examine how such a man could become a public figure of the KR. The revolutionary movement did not trust the intellectuals. Khieu Samphan, said Mr. Sam Onn, did not have a “good class pedigree.”

At this point, the chamber president called for a finish to the day, with the defense team for Khieu Samphan to resume its presentation on Monday, October 27, at 9:00 a.m. The lead co-lawyer for the Civil Parties was given notice that, should the defense for Khieu Samphan rest its case early enough on Monday, the Civil Parties rebuttal could begin on that day.