Witness Recalls Loss of Family Members

After the Trial Chamber sat in closed session all morning and for a great part of the afternoon session, Civil Party Lack Kri took his stance again in the afternoon. He was questioned by both defense counsels for Khieu Samphan on the role of the Vietnamese person Chhuy and his sister-in-law Sun Sam.

Chhuy

In the afternoon at around 14.40, the examination of Civil Party Lach Kri was taken up again. International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé took up her line of questioning again.

Ms. Guissé asked about the person Chhuy, who he had said to be Vietnamese because he married his cousin. She wanted to know whether he remembered when Chhuy arrived in his village and settled there. He replied that Chhuy settled in Pochendam Village in 1975. When she asked whether he was sure it was this late, he said he could not remember the exact date and it could have been 1974 or 1975.

Ms. Guissé referred to a DC-Cam statement by Nheo Sam.[1] The International Lead Co-Lawyer for Civil Parties interjected and said that she did not object to the use, but that the parties had to upload the documents one day before the beginning of the testimony, and not one day prior to the examination of the defense.[2] This prevented the Co-Prosecutors and Civil Party lawyers to have sufficient time to prepare and use these documents.

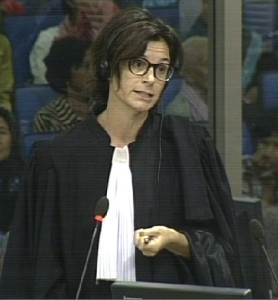

International Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Anta Guissé

Ms. Guissé replied that the documents were indeed uploaded at noon yesterday. They were doing their best to file the documents on time. “We’re doing everything that is humanly possible to abide by the deadlines.”

The Civil Party confirmed knowing the person Nheo Sam. Ms. Guissé said that the person had said that Chhuy arrived in around 1971.[3] Mr. Kri replied that he met him personally in around 1974, but did not know whether Chhuy arrived 1971 or 1972. The same person had said that Chhuy was a serviceman when he arrived. She asked whether this refreshed his memory. At this point, International Co-Prosecutor Nicholas Koumjian interjected and said that how the excerpt was read out was misleading. The person had said that the person was not a soldier and that he came from Phnom Penh and spoke Khmer without an accent. Ms. Guissé replied that the witness had simply said that he or she was not sure in which group Chhuy was in.

The Civil Party said that he did not know whether Chhuy had been a soldier before.

Mr. Kri’s cousin (2-TCCP-869) had said that her husband had been a former Vietnamese soldier who had deserted.[4] She asked whether this refreshed Mr. Kri’s memory. He replied that he never discussed this matter. “I only knew that he was a villager and I never discussed with my cousin Oeun about him.”

Ms. Guissé then inquired whether he remembered what kind of business his cousin practices. He replied that he was a merchant selling fish, while his wife sold cake and vegetables.

His cousin had talked about Chhuy smuggling of opium.[5] He replied that he did not know what Chhuy sold aside from fish. She asked whether he confirmed that Chhuy earned “a very decent living at the time.” Mr. Kri said that Chhuy “was not rich” and he “was not well off”, and lived in a “very small house.”

Turning to her next line of questioning, Ms. Guissé asked whether he remembered that there was an organized return of the Vietnamese in Cambodia to Vietnam. He replied that he lived in the village from 1970 onwards. The Vietnamese people returned to Vietnam “one after another” and only three Vietnamese families remained.

She asked whether he remembered that Vietnamese people returned – not necessarily from his village – throughout Cambodia after the Lon Nol coup d’état. He answered that Vietnamese people may have returned to their country, while some others remained. He specified that he could only talk about his location, but not about the rest of Cambodia.

Attitudes of the Vietnamese

Ms. Guissé then turned to the next line of questioning and said that he had said that there had previously been no problems between Cambodians and Vietnamese. She wanted to know whether there were any problems, misunderstandings or prejudices on the side of the Cambodians vis-à-vis the Vietnamese. Mr. Kri replied that “nothing strange happened” between his sister-in-law and the community she lived in. There were no fights or arguments. “No one hated her. She was a very socialized person and very popular within the village.” She asked whether he had ever heard anyone say that Vietnamese people had a form of conduct that might seem shocking to Khmer people, which he denied. This prompted Ms. Guissé to refer to his interview, in which he had said that his family did not blame his brother for marrying a Vietnamese, because her conduct was very similar to the Khmer behavior, unlike the behavior of other Vietnamese people.[6] She asked what he had meant by that. He replied that “she had Khmer attitude, but the way she spoke was like a Vietnamese.” He further recounted: “my older brother married her with his whole heart.”

Ms. Guissé clarified that she referred to the conduct and not the accent. He replied that she was “like Khmer people in terms of attitude.” His parents “loved Lach Ny’s wife.” Ms. Guissé insisted on the point and asked whether Vietnamese had other attitudes. Mr. Kri answered that his brother had told the people in the village that he married a Vietnamese.

Trial Chamber President Nil Nonn

Ms. Guissé dropped the topic and asked about his brother. He recalled that his brother was well-educated and received a shot training in Germany. He then returned to Cambodia to Phnom Penh. He did not know his occupation after his return. He then returned to his village. “Lach Ny knew many languages.” Lach Ny may have worked in the government. He spoke several languages: Vietnamese, French, English and German. He spoke the four languages very clearly. She then asked whether his brother went to another country except Germany. The President interjected and asked her to clarify how this was relevant for the trial. She said that people had said that intellectual people and those who had been abroad had been targeted. She said that this may have been why the family was targeted.

The President said she could resume her line of questioning and conclude it. Ms. Guissé moved on and asked whether he knew which person suggested the re-marriage of his brother and what position this person held. He answered that it was made by Svay Antor commune with the agreement of the commune. Three spouses were invited. Chhem was the Svay Antor commune chief. Ms. Guissé wanted to know what the attitude of Chhem was towards his brother during the five months that his brother was psychotic. Ms. Guissé replied that his brother slowly became normal again. The commune chief lived around ten kilometers away from his village.

He had said that a person lived next door to his brother.[7] Ms. Guissé asked whether he was referring to Chhem or anoher cooperative chief there. He replied that he referred to the village authorities and not Chhem. The person in charge of the authorities was called Seng. He was from a different village and assigned to take charge of Pochendam Village. His village of origin was around two kilometers away. Seng also lived close to his brother. Seng had said that it would be better to marry Lach Ny to another woman. With this, Ms. Guissé finished her line of question and handed over the floor to her national colleague Kong Sam Onn.

Back to Chhuy

National Khieu Samphan Defense Counsel Kong Sam Onn

Mr. Sam Onn turned back to the person called Chhuy and asked what kind of profession Chhuy engaged in. Mr. Kri replied that Chhuy was a merchant who sold fish. He was not aware of any cross-border trade that Chhuy might have engaged in. He was a merchant from around 1974 onwards when he met him. Mr. Sam Onn then asked what the basis was for his assumption that he knew Chhuy in 1974. Mr. Kri replied that this was the case, because he saw him in 1974, which coincided with the birth of one of his children. Chhuy and his wife came to visit them around a week after the birth. He then corrected himself and said his child was around one month old. The child’s name was Phea, but this child had passed away. He did not have any birth certificate.

Mr. Sam Onn then wanted to know whether he knew his sister-in-law well. He replied that he got to know her in 1968. “She spoke to my elder brother who was fluent in poetry.” His elder brother spoke Vietnamese with her. He heard this in person, because his house was adjacent to theirs. When they spoke Vietnamese to each other, he could not understand them. The house was around three meters away from theirs.

Mr. Sam Onn said that he had testified yesterday that he had heard his sister-in-law speak Vietnamese.[8] Later, he had said that she spoke the Khmer language with an accent.[9] Mr. Sam Onn asked whether he stood by his statement, which he confirmed.

Mr. Sam Onn asked for permission to play a portion of an audio clip.[10] The audio clip was not available, so he read out an excerpt of the transcript.[11] Lach Kri had said that his wife could hardly speak Vietnamese. The Civil Party replied that he could not recall this. He denied having made that statement, because she spoke Vietnamese. Mr. Sam Onn asked how this discrepancy could be explained. Mr. Kri insisted that he had never said that she did not speak Vietnamese. “I cannot tell you about it, because I did not say it.” When the Civil Party could not shed more light on the matter, Mr. Sam Onn finished his questioning.

The President thanked the Civil Party and instructed him that he could make a Civil Party statement of suffering.

Mr. Kri addressed the court and said the following:

Civil Party Statement

Again: my respect to Mr. President. I lived under the period of Democratic Kampuchea regime and my life was miserable. It was also miserable for my parents and family members. Our lives were so miserable under the regime […] and nothing could compare to the misery that we received. We were evacuated from Prey Veng province to Battambang province. It took us 3 days to take the journey. […] We had to make another journey which was around seven or eight kilometers long. I had elder parents so I had to carry both of them […] and my wife had to carry our belongings on her head. And not even an hour after our arrival we were [separated]. I was separated from my wife and [my family] and this inflicted to. much pain on me. […] [After two months], a big meeting was held at Ang Rumleang. And there were thousands of people who were called to attend that meeting. […] And three days after that, I was assigned to build a house which was three meters by two meters near a hill. And about a week later, I was assigned to catch fish at Tonlé Sap River or lake. I walked to the area and it was around 6 pm.

And there were ten Pol Pot soldiers who were walking behind us and they actually opened fire upon our group. I was fleeing the scene and I don’t know how many casualties they inflicted on us. There were 12 of us who survived […] We were running and heading to Pursat. We were without food for a few days. And they made an announcement and I heard the broadcast on the radio that I was the ringleader to lead a rebellious group. But in fact, I was not involved in any rebllious activities. […] I was fleeing. And we had to cross a number of battlefields. And while we were crossing a battlefield, four of us were shot dead and there were eight remaining. And then we had to run crossing another battlefield, we were fired upon and I was hiding myself upon a small hill and I saw many dead bodies in a pit nearby that hill, maybe 20-30 dead bodies. And then two of our group members were shot dead, so there were six of us left. One woman was killed. […] Then we had to come across the third battlefield, which was a boundary of Pursat province. At the time, a woman from our group was shot dead and there were only five of us survived. And at that time, we did not have any belonging with us, only the clothes that we were wearing. And actually while we were fleeing, our clothes got caught in the forest and we were almost naked. So I actually had to take off my pants for the women to wear […]. We had to run […] and the five of us were arrested [by the Vietnamese] and accused of being the Pol Pot clique. I was interrogated and through the interpreter I was asked whether I was a Pol Pot clique or not, and I said of course not. I said I was a villager of Prey Veng province. And then I was accused of being Pol Pot clique. And I was threatened that I didn’t tell them the truth. […].

He then asked the Vietnamese person who interrogated him:

But then also: where were you during the Pol Pot regime? Where did you flee to? And the person said “I was living in Pursat”. And I said that if you lived in Pursat, you were also part of the Pol Pot clique. Then the person hit me on my head with a pistol and I was bleeding. And I was cuffed in a prison there. And I was imprisoned there for one month and twenty days. Finally, thanks to Excellency Prum Deng, I didn’t know where he came from, but he came through the area, and I knew him because e was from the [same area as me] […] and I told him that I knew him because his house was not far from mine.

Then he told them to release me. Then he questioned me and after the questioning period he told the Vietnamese to release me, but the Vietnamese people did not release me. I was still handcuffed. That happened after the 7 January 1979. I was still detained. And later on, I saw Lach Ny and Lach Ny was told that I was detained by villagers, so he came to me. Then there were around 100 people who begged for me to be releases. And upon my release I was told that my parents and family members were killed because I had left the village […] However, I was told that I would be killed anyway.

At this point, the President interrupted the Civil Party and instructed him to be brief. Mr. Kri finished his statement of suffering by saying that

International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud

I lost my parents, my wife, my children and my siblings and some other family members. That is all I want to say, Mr. President.

At this point, the President gave the floor to Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud, who said that he had not given the opportunity for the Civil Party to ask the question that had been sent to the Chamber. There was a small discussion about this, after which the President asked the Civil Party whether he had any questions.

Mr. Kri had two points:

For those senior leaders of Democratic Kampuchea regime: Are you aware that your subordinates engaged in killing of the people? Second, what was the reasons for you to instruct your subordinates to kill the people?

The President informed the Civil Party that the accused continued to exercise their right to be silent. The President then announced that the hearings would continue on Monday, January 25 2016 with the testimony of Civil Party 2-TCCP-869.

[1] D230/1.1.49b.

[2] E341/1.

[3] 00848446 (FR), 00822156 (EN), 00451710 (KH).

[4] E3/7809, at 00486104 (FR), 00282563 (EN), 00271368 (KH).

[5] E3/7562, at 01157781 (EN), 00034081 (KH).

[6] E3/5640, at 00657815 (FR), 00034400 (KH), 00645400 (EN).

[7] E3/5630, at 00891891 (FR), 00895421 (KH), 00678290 (EN).

[8] Testimony of January 20, 2016, at around 13:50.

[9] Ibid., at around 15:50.

[10] D166/12R.

[11] 08:58-09:10.

Featured image: Witness Lach Kri via audio-visual link (courtesy by ECCC: flickr).