Propaganda, Torture and French Colonial Heritage: Looking into the Methods of the Khmer Rouge

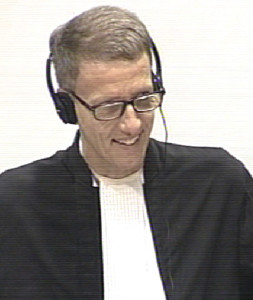

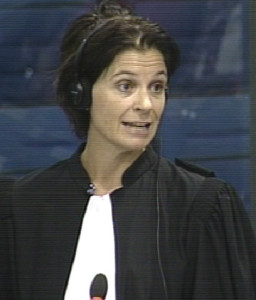

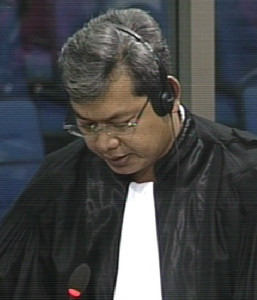

The witness, the Judge, and the Counsels gave an abundance of information about a wide range of issues, as the day was divided between three focal points. Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne concluded his interrogation by touching on Vietnamese prisoners at S-21 before handing the floor to the Co-Counsel for the Defense of Nuon Chea Victor Koppe. Mr. Koppe attempted to set the brutality and the torture methods from the Khmer Rouge regime in a broader scope: heritage from the Lon Nol regime and the French colonial era. The last session of the day was given to the Civil Party Lawyers, Marie Guiraud and Pich Ang, who presented on the upcoming implementing educational, cultural and artistic projects. The reparation for the victims as well as an inter-generational dialogue to guarantee the non-repetition of the traumatic Khmer Rouge period were the essence of these measures.

Medical experiments at S-21

Referring back to what the witness had said earlier in his testimony, Judge Lavergne asked more details about the live surgery that was performed on Ta Chea’s wife[1]. Duch said he did not authorize it and could not recall any other instance of this experiment being performed. An annotation from his own hand on the file of a 23-year-old woman seemed to contradict this statement, but the witness did not change his position[2].

The Judge then showed the Courtroom an extract from the documentary film “Die Angkar” and made reference to a medic who worked at the prison[3] [4]. In a medical booklet, it was described that a 17 year old woman had “her throat slit, and her abdomen pierced” before being “put in water for two hours”. Then, she was apparently beaten, put back in the water for a whole night and the process was repeated several times. When asked if this description refreshed his memory, Duch answered:

“It seems like they played around with that detainee, that it was not a medical experiment.”

He elaborated that he had asked Hor to conduct this experiment in the context of an investigation after a body emerged from a water point, in order to find out how many days bodies could stay in the water before they resurfaced.

Yuon soldiers and war propaganda

Last Monday, witness Duch recalled that Nuon Chea had ordered him to interrogate Yuon (Vietnamese) S-21 prisoners and broadcast their confessions on the radio[5]. Brother Nuon requested that they be aired twice a day for five or ten minutes. They were the subject of several obligations, including those published in a pamphlet by the information service of the Democratic Kampuchea Ministry of Foreign Affairs: the confessions had to be testimonies of the invasion of Cambodia by the Vietnamese (published in July 1978)[6].

The name of Vu Ding N’go, a military Vietnamese detainee, appears on two different lists[7]. Duch recognized him, and explained that the two lists used to distinguish soldiers and spies. According to him, some soldiers tried to pass off as civilians so they would not be captured. The witness recalled that N’go was transferred to work with the new government. Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne then linked this former soldier’s confession as being a part of the pamphlet mentioned above.

Co-Counsel for the Defense of Khieu Samphan Anta Guissé objected on the same grounds she objected on Monday and Tuesday[8]: “the contents of confessions are being expressly quoted, and the witness is being asked to comment on the circumstances, which is not in accordance with the Chamber’s decision and the Convention against Torture.”

Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak, who was the one to have answered Ms. Guissé these past few days, said that in the case of the radio transmissions, the correlation made between the S-21 confessions, tainted by torture, and the broadcasts was not proven. There was no proof the propaganda material was obtained under torture. The Judges discussed the matter among themselves for several minutes, leading them to uphold Ms. Guissé’s objection.

The Judge had to move on, and had Duch clarify that the Vietnamese soldiers were interrogated primarily so that they would confess to establishing the Vietnamese plan to integrate Cambodia in the Indochina Federation.

S-21 biographies of the Vietnamese and the Torture Convention

Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne took further interest in the short biographies attached to the files of S-21 prisoners, as described thoroughly during witness Suos Thy’s testimony several weeks ago[9]. Ms. Guissé raised the same objection as earlier, arguing that when such biographies mentioned details such as the reason for the arrest, there was a risk that they could have been obtained under torture. If a prisoner “confessed an offence under duress, then we fall under prohibited territory”, she maintained.

Mr. Lysak, as well as Judge Claudia Fenz, did not agree, especially because these biographies were not statements by the prisoners themselves and had previously been used in Court proceedings. Ms. Guissé insisted that any element relating to the content of their confession was not to be used – she pointed out an instance in this Court during which her colleague Mr. Victor Koppe, Co-Counsel for the Defense of Nuon Chea, was proscribed from referencing a similar document (April 24, 2015).[10] Mr. Lysak agreed to this presumption when looking at the source of some information: “if the document said they were fishermen, it has to be clear that this came from prison staff that reported it, and not the prisoner himself.”

This debate showed that article 15 of the Torture Convention, though it seems straightforward, can be subject to different interpretations depending on the nature of the documents studied. A confession can certainly be tainted by torture – but the answer is not as evident when it comes to documents that are presumably more objective and contain elements that may relate to the confession. Eventually, the Judges decided to sustain the objection, though Judge Lavergne indicated that he dissented.

Using Vietnamese prisoners as political tools

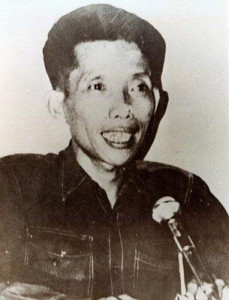

Young Kang Kek Ieu, alias Duch, posing for a picture at the military prison in Phnom Penh. (Photo credit: HO/AFP/Getty Images)

After the break, Judge Lavergne resumed his questioning and had the witness say that typically, after Vietnamese nationals were sent to S-21, their fate was sealed: the decision was made by the upper echelon that they were spies. However, the case of the Vietnamese interpreter who was spared to assist Mam Nai, Pa Tan Chan, alias Chan, provided some crucial insight as to how Vietnamese prisoners were treated.

A video excerpt from an interview of Pa Tan Chan by Rithy Panh was shown to the Courtroom[11]. His eyes were lost, looking at old photographs of Vietnamese detainees at S-21 in a room where an old photograph of young Kaing Guek Eav, Duch himself, was hanged on the wall.

“At the time, I was in the prison. […] I had to tell the stories which had nothing to do with me. They wanted me to confess. To that end, they beat me with a whip […], and when I did not reply they beat me with a club. […] I bear the scars. They beat me. I suffered. I was a victim. They were always right. Finally, they electrocuted me, they attached pinchers to both ears, and the current went through my brain, I sometimes became unconscious. […] If I woke up, they brought me back to interrogation. On another occasion, they used another technique: the extraction of my nails. […] I still bear the marks on my hands and feet. They removed my nails, it was so painful. The pain was unbearable, it was as if I was dead. […] They plunged my head into a bucket of water. […] They would then proceed to hang me there downwards. […] I told myself that I was going to die but told the truth nonetheless. […] They interrogated me for information, they knew that I spoke Vietnamese and that must have signed my death warrant. But they spared me nonetheless so I could work for them. […] They shackled me and handcuffed me, and told me to translate and interpret. If I said something wrong, I was also assaulted.”

Chan went on to describe that interrogators wanted the

Vietnamese prisoners to confess they had come to invade Cambodia and that they were executed and buried later on, possibly at Choeung Ek. At the time, the Vietnamese were not in Cambodia, according to him. Chan also added that when the Khmer Rouge did not succeed in arresting Vietnamese soldiers, they took civilians instead, whom they classified as spies. They made them wear the clothes and bear the insignia of Vietnamese troops to take pictures and make them pass off as Vietnamese soldiers. Chan concluded, fiddling with the photographs: “They distorted the proof. They said it was proof of the Vietnamese invasion. [They only wanted to attract] international assistance and sympathy.”

Duch recognized Chan without hesitation, but disputed his testimony. He said that Chan was on the side of the Vietnamese, so “he exaggerated on the torture inflicted on prisoners.” Echoing some of his earlier statements, he denied pulling out nails and waterboarding were methods used at S-21. He also assured that the Vietnamese civilan prisoners were not forced to confess they were Vietnamese soldiers.

Propaganda film

Last week, Senior Assistant Prosecutor Dale Lysak interrogated the witness about a short film shot by Pol Pot’s nephew Theng, which showed the arrest and the interrogation of Vietnamese soldiers. Judge Lavergne pick up the line of questioning and asked if this film was shown during study sessions, notably in 1978 at the occasion of the anniversary of the Khmer Rouge victory of April 17, 1975. This was supported by testimonies of S-21 staff including Him Huy (May 4, 2016) as well as Lach Mean (April 26, 2016). Duch denied this film was ever shown to S-21 staff and said that these two witnesses had no credibility. Duch has alleged several times that the witness Lach Mean was not who he said he was because of a signature he did not authenticate as his. Judge Lavergne clarified this allegation by explaining that the signature was later identified as not being Lach Mean’s[12].

An extract of the film “Cambodia Kampuchea” was screened, which was also shown to witness Suos Thy when he testified in May[13]. The images showed men in Vietnamese military uniforms bowing their heads and speaking, then Pol Pot giving a speech and people cheering. Duch said this was not the film shot by Theng, and that he did not have anything to say on the matter.

This concluded Judge Lavergne’s inquiry about what the witness knew regarding S-21, propaganda and Vietnamese prisoners. He handed the floor to Co-Lawyer for the Defense of Nuon Chea Victor Koppe.

Methods of torture: learning from the French colonists and the Lon Nol regime?

Though a storm raged outside, everyone’s attention was drawn to the Defense. Firm and determined, Mr. Koppe first set his focus on where Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch, had learnt the methods of torture used at S-21. The witness stated this week that Vorn Vet had been the one to teach him about suffocating prisoners with plastic bags, but Mr. Koppe made reference to Duch’s 2009 testimony in which he had said:

“The person who taught me how to torture was the Lon Nol regime. That is number one. The inspector at PJ, he beat the Khmer Rouge prisoners. […] And second, it’s the French regime. The French tortured members of the Vietnamese Labor Party.”[14]

Duch was asked to elaborate on this, but he denied he learnt the techniques that way and asked sharply that Mr. Koppe provide him with the exact transcript of this document. The witness also denied he learnt them from a book he had mentioned in his testimony on June 14th by Ellen Dulles, titled “The Craft of Intelligence” (“Techniques de Renseignement”).[15]

The sound of rumbling thunder made the questioning sound very dramatic, as Co-Counsel for the Defense of Nuon Chea Victor Koppe presented the witness with an extract from Philip Short’s book[16]. The author argues in this book that when looking at interrogations and torture by the French, “much about S-21 is depressingly familiar”.

“Democratic governments have also gone down that road. The French Army in Algeria set up torture centers where conscripts martyrized, suspected fedayeen [Algerian rebels] and then killed them to maintain secrecy, exactly the same justification as was used in Democratic Kampuchea. 5,000 Algerian prisoners were killed in this way in one interrogation center alone. In the country as a whole, the number of such deaths probably exceeded 15 to 20,000 who died in S-21. The factors that led young Roman Catholic Frenchmen violate every principle of justice and humanity they had learnt since childhood were not essentially different from those that governed the conduct of S-21 guards. […] It may be argued that for Khmers it was easier: their religion cultivates indifference. However, S-21 had French carceral antecedents: the shackles used in its cells were inherited from French colonial times. The torture that the Khmer Rouge called “stuffing prisoners with water” had been introduced to Indochina by the French Army, which called it “la baignoire”.”

The witness affirmed it was the first time he heard about this. According to him, shackles and cuffs were made according to instructions by the upper echelon from M-13. Duch had “learnt some lessons” from the Lon Nol regime as well, but “they never got into his personal way of thinking”.

Contemporaneous knowledge

Since the beginning of his testimony, Duch made statements based on knowledge from the time he was working in Democratic Kampuchea as well as knowledge he had subsequently acquired after reading the case file. Mr. Koppe sought to clarify what information was from when, as there were discrepancies between certain testimonies the witness gave at different times:

“I am trying to understand how your memory works.”

Mr. Koppe listed several statements by the witness that showed the disparities and the variations between several of his previous testimonies, but Duch did not admit to it, instead asking for accurate transcripts of the documents being presented to him. [17] [18] [19]

Co-Counsel Victor Koppe insisted:

“I am not giving up on this one.”

Yesterday, Duch estimated that around 10,000 prisoners had gone through S-21. However, when asked about the total number of prisoners in 1999, he stated: “I do not remember.”[20] [21] Duch hammered he was certain that Son Sen had left for the battlefield on August 15, 1977, though some evidence shown this week by the Prosecution as well as a previous interview of the witness himself suggested otherwise[22].

“Mr. Witness, is it true that the moment you received the case file you started changing your testimony as to Son Sen still reading confessions, first to October, then to November 11th, and finally to November 25th just to fit your date into things you saw or read in the case file?”

“What are you asking me? Which date? Which document are you quoting? Could you please give it to me and put it on my desk? […] Next time, please provide me with the full question.”

Visibly irritated by the last segment of questioning, Duch then concluded his testimony for the week.

Civil Parties: focus on the victims

Co-Lawyer Lead for Civil Parties Marie Guiraud took the floor and detailed the outline of the presentation on the reparation projects elaborated in Case 002, eight of which were financially supported and ready to be implemented. These projects, she reminded, are of no cost to the accused. They are financed by outside sources such as non-governmental organizations. Moreover, the reparation projects proposed today will only become judicial reparations if at least one of the accused is convicted.

Ms. Guiraud explained that the projects placed the Civil Parties above all, in line with the fundamental principles of the United Nations in terms of reparations (2005).

Project Number One: Web Application of Khmer Rouge history and education

The project would be implemented by Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center. The web app would explore the main issues and the crimes at the heart of Case 002 thanks to films, education models, photographs, articles, images of the trial, audio files, and the like. There would be a consultation in Court on June 24, 2016 to explain the project.

Project Number Two: Training of the teachers in high schools and universities.

The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) is proposing to organize training sessions for teachers in high schools and universities for Khmer history.

Project Number Three: Arts and Education at Meta House

It is an artistic and education project in a broader sense, supported by Meta House (Young Cambodian Arts). They developed a community theater play, working for Khmer Action Art. The play stresses the acts of courage, resistance and solidarity during the Democratic Kampuchea period. Dicussions between all would follow this play, which would be performed in school.

Project Number Four: Cham minority

Meta House would hold workshops between young Cham filmmakers and victims of the Democratic Kampuchea regime to ultimately shoot documentaries or movies.

Co-Lawyer Lead for Civil Parties Pich Ang then took the lead and explained the remaining projects.

Project Number Five: Forced marriages under the Khmer Rouge regime

The Khmer Art Academy in collaboration with Kdei Karuna, T.P.O, and the Bophana Center. It is a contemporary classical dance production using history and testimonies of survivors. It would explore the gendered impact of forced marriage under the KR. The production would be accompanied by community dialogues to be conducted post and pre-performance and would also collect oral testimonies to be permanently archived in relation to forced marriages under the Khmer Rouge regime.

Project Number Six: voices of ethnic minorities

This project aims at raising public awareness about the treatment of them during the Khmer Rouge regime, in collaboration with Kdei Karuna. Activities include: innovative approaches to facilitate community dialogues; exhibitions, public truth telling and oral history documentation.

Project Number Seven: the untold stories of civ parties participating in Case 002/02

This project is in collaboration with the Cambodian Human Rights Action Committee (CHRAC) and it aims at publishing the personal accounts of civil parties admitted in case 002/02 who could not testify in Court (around 30).

Project Number Eight: rehabilitation: improving the health and the well-being of civil parties

The focus is set on capacity building for health professionals, health support volunteers as well as more health care schemes to target communities.

Project Number Nine: proposition stage

It is a proposition to the Royal Government of Cambodia to go through the administrative body of the ECCC as part of the reparations. The Legal Documentation Center is a partner and it would allow Civil Parties to have access to the legal records related to the Khmer Rouge trials.

Some other propositions include a public memorial center near Battambang Pagoda in Siem Reap province, a public ceremony to commemorate the victims, at Siem Reap or Angkor Wat, a request the government to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism to preserve the art and public infrastructures being renamed to honor the victims.

The President then adjourned today’s hearing. Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch, will resume his testimony on Monday, June 20th. The Defense will have the floor to continue the cross-examination of the witness.

Featured image: Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch. (ECCC: Flickr)

[1] Awaited Testimony of Former Head of S-21 Duch Begins, The Cambodia Tribunal Monitor, June 7, 2016

[2] E3/1671, at 00171142 (KH), 00181798 (EN), 00296035 (FR).

[3] E3/10120, at 01014173 (KH).

[4] E3/719, at 01248192 (EN). Medic: Theng So.

[5] 13/06/2016, at 15h01.

[6] E3/8394, at 00293980 (KH), 00011374 (EN).

[7] E3/8436, at 00086819 (KH) and E3/8492. From the army of Southern Vietnam.

[8] Witness Unravels Chain of Command under Khmer Rouge Regime, The Cambodia Tribunal Monitor, June 13, 2016.

[9] E3/10521, at 01180411-417 (KH), 01191483-495 (EN).

See also Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers’ Submissions Relating To The Admissibility And Permissible Uses Of Evidence Obtained Through Torture, May 21, 2015, http://www.eccc.gov.kh/sites/default/files/documents/courtdoc/2015-06-08%2009:45/E350_3_EN.PDF

[11] E3/2352R, at 01239944-963 (KH), 01241045-59 (FR).

[12] E3/2469 and E414.

[13] E2354R.

[14] E3/5794, 28/04/2009.

[15] E3/347, at 00002511 (KH), 001160132 (EN), 00160896 (FR).

[16] E3/9, at 00396572 (EN) page 364, 00639933 (FR).

[17] E1/51.1, 20/03/2012 at 11h28. General situation in Democratic Kampuchea: “however, if you really want me to only talk about what I knew back then, I’m afraid I might have nothing to say about it, as I was confined to S-21.”

“It is better to arrest 10 innocent people than release one guilty person”. 9/06/2016: “I learnt about it when I read David Chandler.” “I heard it from Brother Khieu: “to keep is no gain, to remove is no loss” and I just said that Mr. Chandler’s quote wasn’t accurate, it was what Brother Khieu said instead.”

[18] E3/1355, at 00242878 (EN), 00239836 (KH), 00239825 (FR). “Following Chandler’s book, Koy Thuon was put into house arrest at a certain date”.

[19] E3/456, at 00198882 (EN), 00198873 (KH), 00198890 (FR).

[20] E3/528, at 00327319 (EN), 00320783 (KH), 00373324 (FR).

[21] E3/65, at 00147525 (EN), 00146487 (KH), 00147100 (FR).

[22] E3/1567, at 00002623 (EN), 00172211 (KH). Interview with Nate Thayer.