Pol Pot’s Nephew Testifies

Today, November 29, 2016, Pol Pot’s nephew and guard Seng Lytheng testified. He told the court about his contact with senior leaders, such as Pol Pot, Khieu Samphan, Nuon Chea, and Ieng Sary. He was first tasked with welcoming guests from zones as well as foreign delegates, and then assigned as a guard at K-1. In the afternoon, Civil Party Kheav Neab was introduced to the court. She mainly spoke about the disappearance of her husband. Her testimony will continue tomorrow.

Pol Pot’s Nephew

Seng Lytheng (2-TCW-287) was born on 17 July 1946 at Prey Sbao Village, Kampong Svay District, Kampong Thom Province. He is Pol Pot’s nephew: his father is the older brother of Pol Pot. The witness joined the revolutionary movement in 1970 as a soldier. He denied becoming a party member. “In 1970, I was in the Vietnamese army.” He returned to join the army in the North Zone in 1973. He was there for a bit over three years. When he was part of the Vietnamese army, he was mostly stationed in Kampong Thom Province and Siem Reap “to provide protection for Angkor Wat.”

After he got wounded, he could no longer fight and was reassigned to a messenger and guard unit. He said that this may have taken place in 1974, but he was not certain. He was based at Chamkar Leu in Kampong Cham Province. The leaders who were located there were Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, and Khieu Samphan.

Mr. Lysak inquired whether he was located near the Stung Chinit River near the Kampong Thom and Kampong Cham border. He replied that he could not recall the location of the headquarters. He was not aware of a code for the office. Mr. Lysak asked what he observed how Khieu Samphan, Nuon Chea, and Pol Pot behaved in 1974 and what they did. The witness answered that he did not understand the important affairs, but that they held meetings quite often. They held meetings among the four individuals.

Mr. Lysak referred to the testimony of witness Phy Phuon of 30 July 2012, in which he had said that Khieu Samphan worked in the office adjacent to Pol Pot’s office. Mr. Lysak wanted to know whether it was correct that Pol Pot, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan ate and worked together on a daily basis. The witness confirmed this.

After April 1975

Turning to the next topic, Mr. Lysak inquired about the living conditions. The witness could not recall this clearly. When Phnom Penh was liberated, he was in a mobile unit. He was then relocated close to the Chinese Embassy. Subsequently he was sent to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to receive guests. He facilitated the relations between China and Cambodia. After he left the Ministry of Foreign Affairs he worked as a guard at Office K-1. This was in around 1978. Mr. Lysak read part of his statement, in which he had said that he was in the “leadership unit”. Mr. Lysak asked whether it was correct that he worked as a guard and messenger at K-1 beginning in 1975.[1] He replied that at that time, he was part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and in charge of receiving guests. He worked there “for a short while” before being sent to K-1. It was located near what is now the so-called White Building in Tonlé Bassac area. Mr. Lysak asked whether he knew the location close to the Royal Palace that the leaders used as houses.[2] The witness answered that he was not familiar with those locations.

Mr. Lysak asked whether he saw any other leaders regularly besides Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary. He replied that the zone secretaries occasionally came to visit. There were around 20 guards who worked inside the compound, but there were also other guards outside. The witness worked inside the compound.

Mr. Lysak pointed to a list of K-1 staff members and highlighted name number five: Teng alias Puol.[3] The witness confirmed that this was his alias at the time. The first person on the list was a person called Lyn, who was identified as the joint chairman for K-1 and K-4 and who was married to Sen (who had testified in court before). The other people on the list were the guards who stayed inside the compound. He did not know when Lyn got married. The witness got “married previously”, because he “liked the woman.” He was married when he was at K-1. They were introduced to each other and they liked each other. Hence, their marriage was arranged. She worked at the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. The marriage was organized for them by the guard unit. Other guards participated in their wedding. They were the only couple who was married there. They were married around a week after they were introduced to each other.

The guards at K-1 were under the supervision or Pauk. Syn was not a chairperson or deputy. Mr. Lysak asked about the ninth name on the list: Leng. The witness confirmed that this was the Leng who he previously had identified as Pol Pot’s driver.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

K-3

The guards for Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary and Khieu Samphan were located at K-1: Tang, Syn, and Lang. The names listed for K-3 were not guards at K-1. A person called Sa My was identified as chairperson of K-3 and ethnic Jarai. Ta Tuch was from the West, Ta Mok and Sao Phim. Mr. Lysak asked whether Tuch was also known as Koy Thuon. He then inquired how he knew Sao Phim and Ta Mok. He said that they were part of the zone committee, so people knew them. Mr. Lysak asked whether he knew Ruos Nhim and ever saw him at K-1. He took letters for Sao Phim three times, but did not deliver other letters. He did not know who the author was of the letters. He only knew that it was Pol Pot who gave him the letters. Mr. Lysak read an excerpt of his statement, in which he had said that he delivered letters to Tuch.[4] The witness denied this and said that he only delivered letters to Sao Phim. He said that this took place “perhaps in 1978.”

Dam Worksites

He escorted Pol Pot when he went to inspect the 7th January Dam and Steung Dam construction sites in Kampong Thom. Mr. Lysak asked whether he ever went to the 6th of January Dam with Pol Pot. He replied that he was not sure whether it was the 7th January Dam or 6th January Dam. He could only remember that it was in Kampong Thom. He did not know the details about Pol Pot’s acts at the dam site. Pol Pot personally met workers. There were a few children at the dam. He also saw some militiamen. The witness did not pay attention to their working conditions, since he focused on guarding Pol Pot. “There were no remarkable problems among them.”

Nuon Chea never delivered speeches, he said. To refresh his memory, Mr. Lysak quoted his interview, in which he had talked about study sessions conducted by Nuon Chea and Pol Pot.[5] They went to Borei Keila for study sessions. He did not accompany Nuon Chea when he gave the study sessions. Mr. Lysak wanted to know how he knew that Nuon Chea often went to the zones to open study sessions. He replied that he did not know which locations Nuon Chea went to, but that he knew that he went to open study sessions. Mr. Lysak quoted his statement, in which he had listed the content of the study sessions. Mr. Lysak inquired how he knew about the content of the study sessions. He replied that he could hear parts of the content over loudspeakers when he was standing guard. The locations of the study sessions were at Borei Keila. He could hear some of the topics, but not everything.

Mr. Lysak asked whether he remembered the location Chbar Mon in Kampong Speu Province, which the witness denied. He did not attend “those major events”, because he was a guard.

The floor was handed to the Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyers. National Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Pich Ang asked whether there was any river flowing through 7th January Dam. He replied that Stung Chinit passed through. It was “a large dam.”

Mr. Ang then asked about his marriage. He recounted that they had to make requests to the respective units when they wanted to get married. Sometimes, their unit would encourage them to get married. When their unit determined that it was time to get married, they would be asked whether they wanted to get married and a wedding ceremony was organized. The chief of the respective unit would call a woman and inform her of an arrangement to get married if she requested it. Mr. Ang asked whether it was practice that the respective unit chief would make arrangements and whether there was a policy that they had to get married when they reached a certain age. He denied the existence of such policy and said that they had to be mature enough to marry.

No people from other units attended the ceremony. The woman would be sent to his unit for the ceremony once both man and woman agreed. They were advised to hold each other’s hands, build a life together and to strive harder to support the nation and people. With this, Mr. Ang concluded his line of questioning and the court adjourned for a lunch break.

Chinese Delegates

After the break, the presiding judge Nil Nonn gave the floor to Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne. He worked at the location where he welcomed Chinese visitors for nearly one year. He said that he welcomed Chinese technicians. There were no high-ranking Chinese officials that he welcomed. Judge Lavergne mentioned a few names of Chinese leaders, but the witness had only heard of the name Ta Chay, he said. However, he was not close to the visits of Ta Chay. He travelled to China.[6] He went there twice. Pol Pot met Chinese leaders there. He also accompanied Ieng Sary to Vietnam before the fall of Phnom Penh.[7] He denied having welcomed Westerners.

Judge Lavergne inquired whether he was in charge of delivering liquor to the zones, which he denied. He said he delivered gifts. He delivered them to the East Zone, including Sao Phim. He said Sao Phim and Pol Pot were close to each other.

Photographs

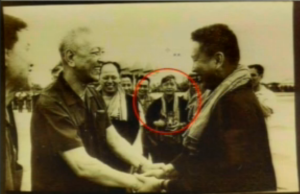

Geng Biao and Pol Pot. The photographer in the background is not the witness as presumed by Counsel Koppe.

The floor was handed to the Nuon Chea Defense Team. Counsel Victor Koppe asked whether it was possible that he joined the revolutionary movement earlier than 1970. He said that he was in the secret insurgency movement before the coup and joined the Vietnamese army in 1970. He confirmed that he was imprisoned before 1970. “I was jailed for 20 years.” He served two years before being released. In 1970, he and his brother “had no relationships” with Pol Pot. He learned photography in the jungle. He also studied photography in China while he was stationed at Office K-1. He took photographs when Pol Pot received visitors. Mr. Koppe showed a photograph and asked whether he was one of the persons on there, which the witness denied.[8] He said that the person to the left was Ta Mok. Mr. Koppe said that

this person looked like a high-ranking Chinese official called Geng Biao. He answered that he did not know who this person was.[9] Presented with another photograph, he denied having taking it. He recognized Pol Pot, Nuon Chea and Ieng Sary. He said that it was possible that Sao Phim was seen. Presenting yet another photograph, Mr. Koppe asked whether this was Sao Phim.[10] The witness was not certain. Mr. Koppe gave the references for his belief that Geng Biao was seen on the photograph.[11] He denied having taken any of the photographs presented to him.[12] Mr. Koppe then showed a photo of the photographer Nhem En to the witness.[13] There was a separate unit of photographers, but he was not in that unit.[14] Mr. Koppe asked whether he was involved in the filming of Vietnamese prisoners, which the witness confirmed. He recounted that it was a documentary film of one Vietnamese. He was tasked to make that short film. The person was a prisoner of war. Mr. Koppe read an excerpt of the testimony of Duch, in which he had said that the film was shot on Mao Tse Toung Boulevard.[15] He said that everything had arranged by Pang for him to shoot the film. He did not “grasp the full extent of [Pang’s] work.” Pang was in charge of giving them assignments and interacted with Pol Pot.

The witness did not recognize the handwriting of the list that the Prosecution had presented to him. He would address Pol Pot with Bong Pol, Bong Nuon Chea, Bong Khieu Samphan. They addressed most of the cadres with bong. Some people would address them as Om or Ta. He did not know how they were addressed in telegrams. He said that “the document was made up by S-21, either by Duch or Phorn.[16]

Mr. Koppe asked whether the witness spoke to a Cambodia Daily journalist, namely Thet Sambath. He said he could not remember, but that many journalists came to interview him. Asked about Pol Pot, he recounted: “He was a polite, gentle person, and he was friendly with people. […] He was not an arrogant person, and he never used any inappropriate words that were abusive to people. […] He gave good advice. I did not see him as a brutal person.”

When Mr. Koppe inquired about an attempt to poison Pol Pot, he said that he had heard about the case. He heard that they were the people who gave him medicine. He was not aware of a visit of two foreign journalists and the killing of one.

At this point, the President adjourned the hearing for a break.

Mr. Koppe showed a video clip on screen.[17] The witness denied being involved in the shooting of the movie. With this, Mr. Koppe concluded his line of questioning. The Khieu Samphan Defense Team did not have questions for the witness. The president thanked and dismissed him.

New Civil Party: Kheav Neab

Civil Party Kheav Neab was born in 1952. She had two children with her first husband and four children with her second. The floor was handed to the Civil Party lawyers. International Civil Party Lead Co-Lawyer Marie Guiraud asked where she lived prior to 17 April 1975. She lived in Damrei Slap in Kampong Thom. She got married with her husband in 1973. Her husband worked in the village, as he worked for the cooperative. By 1974, her husband was sent to the battlefield. After the liberation in 1975, her husband worked in Psar Thmei (Central Market) in Phnom Penh. Her child was born in early 1974. Her husband worked at Ministry 870, which was in charge of distributing vegetables and meat, she said. Her husband was not a cadre, she explained.[18] He was a group leader when he was at the battalion.[19] She was tasked to cook rice for the evacuees. Khieu Samphan distributed food to the evacuees. She saw Khieu Samphan and asked her husband, who told her that it was Ta Khieu Samphan. She saw him only once. She could not recall the exact date, but it happened after Pchum Ben. When Ms. Guiraud asked about the fate of the evacuees, Ms. Guissé objected and said that it was outside the scope of the trial. The Civil Party did not know what happened to her husband. He disappeared, but she did not know whether he committed any wrongdoing. Ms. Guiraud pointed to a list of 1978 and inquired whether the name rang a bell.[20] She replied that she knew her husband by the name Keng Choeun. He was 25 years old in 1978. She therefore confirmed that this was her husband’s name. She also recognized Keng Nhe and Run on the list, who were arrested at the same time. She asked her child where her husband was, and her child told her that he went with Nhe. Her husband disappeared since then. She had to leave Phnom Penh. She was seven months pregnant when she was separated from her husband. She arrived at a mountain. When she returned from the mountain, she delivered her baby. This was in 1979.[21]

At this point, the president adjourned the hearing. It will resume tomorrow, November 30, 2016, at 9 am with the testimony of 2-TCCP-258 and 2-TCCP-1063.

[1] E3/462, at 00204024 (KH), 00223563 (EN), 00491959 (FR).

[2] E3/37, at 00156676 (KH), 00156755 (EN), 00156682-83 (FR).

[3] E3/858

[4] E3/462, at 00204025 (KH), 00223564 (EN), 00419960 (FR).

[5] E3/462, at 00204025 (KH), 00491960 (FR), 00223564 (EN).

[6] E3/462.

[7] E3/462.

[8] E3/3258.

[9] E3/3250, at P00416551.

[10] E3/3259, at P00416599.

[11] E3/3479, at 00442826 (EN).

[12] E3/3236, at P00407223.

[13] At 00162874.

[14] E1/419.

[15] 16 June 2016, at 11:07.

[16] E3/82, at 00398187 (EN), 00398193 (FR), 00398179 (KH).

[17] E3/3015R

[18] E3/6325, at 01114153 (EN), 01152692 (FR), 00544168 (KH).

[19] E3/6425, at 01069300 (EN), 01051394 (FR), 00581517 (KH).

[20] E3/10454, at 01018812 (number 14).

[21] E3/10604, 12831.

Featured image: Witness Seng Lytheng (ECCC: Flickr).