ECCC Grounds Crowded As Defendants Speak On Final Day of Case 002/01

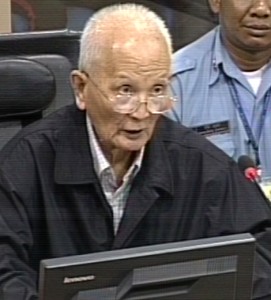

The mood was expectant this morning at the ECCC as trial 002/01 prepared to open its final day. Just after 9:00 a.m., chamber president Nil Nonn handed the floor to co-defendant Nuon Chea. Electing to appear personally rather than via electronic feed from his usual place in the holding cell, the 87-year-old launched into his closing remarks on this historic case.

Nuon Chea proclaims his innocence

Not two minutes passed before the large crowds in both the gallery and media rooms first heard his main point: “It is clearly indicated I was not engaged in any commission of crimes as alleged by the co-prosecutors. In short, I am innocent in relation to those allegations,” he asserted.

Nuon Chea then spent about an hour addressing the court before taking a scheduled break as requested in deference to his health. He began by airing some frustrations with the judicial process surrounding his trial. The search for truth and justice, he said, relies on concrete and credible legal evidence. Thus one justification for exoneration he pointed out was that, he said, “The prosecutors have failed to provide sufficient evidence of the crime I am accused of.” In addition he cited other grounds for his release due to the fact that “Some of my rights are not properly guaranteed [in this trial], namely my right to a speedy trial, a right to legal defense, a right to a fair trial, and other rights guaranteed under national and international law.”

Nuon Chea then spent about an hour addressing the court before taking a scheduled break as requested in deference to his health. He began by airing some frustrations with the judicial process surrounding his trial. The search for truth and justice, he said, relies on concrete and credible legal evidence. Thus one justification for exoneration he pointed out was that, he said, “The prosecutors have failed to provide sufficient evidence of the crime I am accused of.” In addition he cited other grounds for his release due to the fact that “Some of my rights are not properly guaranteed [in this trial], namely my right to a speedy trial, a right to legal defense, a right to a fair trial, and other rights guaranteed under national and international law.”

For the next 45 minutes he offered his version of his roles and activities in the CPK, especially during the years in question, 1975 to 1979. The goal, he said, was to “add some important points so Your Honors can understand more clearly about my innocence and integrity concerning the allegations.”

Asserting, “Everything I say is true,” Nuon Chea addressed the following points:

- He had no power and no authority or connection with the commission of the crimes during DK period, he said. In his main role as Deputy Secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) he educated CPK members and disseminated propaganda materials. “I never educated them to exercise arbitrary authority or behave badly towards the people,” he said. “Instead I educated them to love, respect and serve the people and the country. I never educated or instructed them to mistreat or kill people, to deprive them of food or to commit any genocide, I always taught and educated CPK members and soldiers the main principles of the CPK to make them do their work and serve the people properly.” He then delineated Article 2 of the CPK statute on this topic. “I always educated party members to refrain from exercising excessive authority,” he said, building on the theme of helping CPK members to build “knowledge for them to be patriotic, protect the nation, love the people and have good internal solidarity for the purpose of protecting and building a country to develop and prosper and have independence and prevent any country, big or small, near or far from invading or colonizing Cambodia.” He continued with talking about the need, indeed, duty, to protect the motherland by “smashing” invading enemies, as well as strengthening security and implementing internal stability “properly, so the revolution can develop and prosper.”

- He, as vice-president of the emerging communist movement in Cambodia, was put in charge of building the party’s relationship with the communist party in Vietnam, since the president Pol Pot, was otherwise busy. “I joined the CPK in 1950,” he said. By then, the Vietcong had infiltrated Cambodia, both in the army and the population, and, “From that time I learned of Vietnamese trickery and secrets towards Cambodia,” he said.

- He was with the group who established the first CPK headquarters independent of the Vietnamese communists. Referring to the Vietnamese communists’ “tactics and strategies to control the CPK politically, economically and militarily,” Nuon Chea related how, in early 1964, Pol Pot liberated the CPK from Vietnamese control and the CPK Central Committee created “Office 100,” which was later relocated to Ratanakiri Province. In 1970, he reviewed, the CPK movement expanded after the coup against the Prince Sihanouk on March 18 and the People’s Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea (PRAK), the “Khmer Rouge”, expanded. At the same time, 3,000 Cambodians went to North Vietnam for training, and when they returned in mid-1973, they were appointed to work in the party line and within PRAK, he said, a move that ultimately showed Vietnamese trickery to control the CPK. Nonetheless, he said, the CPK under Pol Pot’s leadership in the early 1970s was able to implement its core principles of independence, self-mastery, self-reliance and deciding its own destiny.

The defendant went on to relate deep Vietnamese “trickery” that went unrealized by the leaders of the CPK. Nuon Chea then said that the CPK discovered that Vietnamese agents had infiltrated in order to destroy the revolution, kill Cambodian people, and annex territory (long an ambition of Vietnam). A history of Cambodian/Vietnamese conflicts ensued and later amplified with Vietnamese control of Cambodia from 1979 to 1991, ceasing only with the October 23, 1991 Paris Peace Accords.

Really, Your Honors, the fault lies with Vietnam

By his statements, Nuon Chea would have the court believe that “acts of depriving food from the Cambodian people and killing them were contradictory to the reasons and policies of the CPK,” and that instead, based on these grounds, “those acts were really the acts committed by Vietnam. The CPK were pained to learn we (the CPK) were deceived by the Vietnamese, which “led to the deaths of our own people and the destruction of our own country,” said Nuon Chea.

He went on with the early history of the CPK and its relations with the Vietcong. Diplomatic relations were severed when Vietnam invaded Cambodia. Military commands to engage in battle for the DK were the responsibility of Son Sen. Nuon Chea was, he said, simply in charge of legislation. Yet, he said, “the war in Cambodia had just ended and the war with Vietnam continued. We did not have sufficient time to legislate many laws in this short time. Considering the condition of Cambodia, legislation was not a main priority.”

He went on to speak on Communist doctrine and how, in the regime, “the party leads and the state governs,” but that in the DK, the balance of power as shared between executive, legislative, and judiciary branches as stipulated in the DK constitution was “merely symbolic in reality. The legislative and judicial branches did not fully function, and only the executive branch was functional, with Pol Pot the appointed Prime Minister with all executive power to lead and control the party line.” Nuon Chea’s point for going into so much detail finally became clear: “No one could replace him [Pol Pot]. Based on this, it shows clearly I had no effective power in governing or implementing the tasks of the executive branch.”

With regard to other allegations of positions he held in the timeframe delineated by the trial, Nuon Chea denied having “any other position. I was dumbfounded when the co-prosecutors alleged I was an acting Prime Minister, a member of the Central Committee, linked to S-21 management. That statement is completely untrue and not backed up by any key evidence,” he said.

Nuon Chea also denied allegations that he was a member of the Central Committee for military affairs, saying that was Son Sen’s province. “I never met, never supervised, or ordered Duch to mistreat or kill anyone,” he asserted. ”Everyone should be aware that soldiers or security personnel will never listen to anyone besides their own commanders, so there is no reason Duch would listen to me. I only heard his name after 1979.” Nuon Chea goes on to accuse Duch of sidestepping his own responsibility for what happened at S-21. “I did not engage in any of those tasks and there is no evidence to prove I did it,” he said.

His purpose for participating in the CPK regime was, “to liberate the country from colonization and defend us from other countries whose ambition was to swallow Cambodia. I love my people. I had no reason to commit genocide against my own nation.”

Turning his attention to the accusation of his involvement at Toul Po Chrey, he cites, again a lack of evidence, especially the alleged killing of soldiers. “As far as I know,” he said, “the CPK never established any policy to authorize use of force to kill former Lon Nol soldiers, or any person for that matter.” The policy he reported for POWs was to forgive and pardon. “To make a revolution is to gather forces,” he said, and “if those people were killed it was against CPK policy.” He then reminded the court of the defense’s assertion that there was confusing and contradicting evidence regarding number of executed, the trucks that carried them, and what those who entered the area found in the aftermath. He called this evidence unconvincing, incredible, and “filled with lies.” Besides, he added, “as a leader, do you think we had time to deal with such a situation?” He and his compatriots were busy, he said, with the task of real importance being to preserve livelihoods and protect the country from invasion.

Combat strategy, blame, and the body of the crocodile

Next, Nuon Chea took listeners down the alley of history once again, to review that violence is the province of nations at war. Many CPK members were secretly executed, arrested, tortured, or disappeared every day before he decided to join CPK. He reviewed the violence of French colonialism, which had been visited on his country for nearly a century, complete with landowner-peasant tensions (that peasants always lost). He spoke of the rapes, killings, and beheadings of the US-backed Lon Nol soldiers and of recent Cambodian history. He wondered why some of those actions weren’t being labeled “genocide,” or “crimes against humanity.” Even the 1979, Vietnamese invasion and occupation of Cambodia followed years of fighting (including shellings on refugee camps) with many losses of life. “Is this not a plan to kill people?” he asked.

For some time, Nuon Chea continued on this line of thought in an apparent effort to link reality and the existence of a systematic plan “If killing in a war is treated as a systematic plan,” he said, “why does the prosecution fail to prosecute the other party to the war?” Of course the CPK made a plan, he said: A plan to engage in a war to liberate the country from destruction. Combat strategy was something leaders used to fight the enemy. “This is not an illegal act,” he said, listing five countries with histories of civil war where factional groups had plans to destroy their enemy.

“If such is a criminal intent,” he asserted, “leaders of those countries whether they are government or opposition group leaders must be prosecuted, especially the United States, Vietnam, and other Cambodian leaders. They should not bring to trial the body of the crocodile, and let the head and tail escape.”

Nuon Chea returned to the question of intent to kill when wars have ended, and the temporal scope of this trial (17April, 1975 to 6 January, 1979) He summarily rejected the prosecution’s allegation that there is a legal basis for satisfying elements of the crime by demonstrating an intention to kill. It bears no legal value, he said.

As the time was nearly 10:00 a.m., Nuon Chea’s counsel, Son Arun interrupted what appeared to be a perfectly vigorous delivery to request that his client be allowed time to rest. Chamber president Nonn called for mid-morning break until 10:15 a.m.

Revisiting the decisions behind the Phnom Penh evacuations

When everyone was back in place at 10:15 a.m., Nuon Chea turned his attention to the topic of evacuation. He denied that the evacuation of Phnom Penh was a forced evacuation. He revisited in detail the assertion that the Americans might bomb, and the impending catastrophe of food shortages. He reminded listeners that, at that time Cambodia did not receive any foreign aid or assistance.

It was a pressing circumstance, said Nuon Chea, so the CPK devised a plan to evacuate people to regions/provinces rich in economic resources and rice; those resources would then feed the evacuated people, who would in turn be required to join in production activity. All members of the Central Committee attended that meeting, he said. The Northwest zone agreed to receive 1.5 million evacuees and the West and Southwest zones agreed to take the rest. For implementation, he said, each zone had autonomy to coordinate itself to facilitate the evacuation. “Evacuation proceeded on a voluntary basis, without coercion, violence or any killing,” said Nuon Chea. “It was implemented by clear information explained to the people to understand the risk of being bombarded by the U.S., and the need to resolve living conditions of the people and self-construction of the country.”

Nuon Chea went on to assert that people understood the situation and the “pressing need” to go to the country. They “supported and loved the revolution.” He cited the recent experiences of the population and the shelling of the city by Lon Nol soldiers equipped with artillery (provided by the U.S.) that had devastated the country. “Isn’t this inhumane act?” he asked. “A crime?”

Turning to the allegation that the DK regime was a “slave state,” Nuon Chea said plainly, “It is simply not true. The CPK did not struggle to liberate the country for the purpose of transforming its people into slavery as alleged.” In his view, the CPK liberated the people from slavery caused by deeply rooted corruption and injustice He described the scenario of rich landowners taxing the peasants until they had to borrow money, only to be faced with usurious interest rates which led to losing their land and being forced to work as slaves to work off their debt or forced to sell their children to work for others, becoming poorer and poorer. His goal, said Nuon Chea, had simply been to build a country where people could “live equally, with independence, self-mastery, self-reliance and the chance to decide their own destiny and that of the nation.

The Four-Year Plan: Dessert Every Day

Nuon Chea went on to describe what Cambodia should have looked like within four years, if the Standing Committee’s plan had worked. By building socialism in all fields and following the Four-Year Plan, people would have reaped the following rewards:

- Each person would receive 312 kg rice per year and have three meals a day with two courses, (soup and a fried dish);

- Plus dessert every three days in 1977;

- Dessert every two days in1978;

- Dessert everyday from 1979 onwards;

- Work for eight hours a day and have three days off per month, and;

- Maternity leave would be for two months; sick people could rest as needed.

In addition, the regime was planning to increase the use of machinery to reduce workload of the people. Nuon Chea asserted that this plan demonstrated that the CPK stance was not to force people to work too hard. And, he admitted, it was only after 1979 that he learned that local cadres lied to him about people working so hard.

Nuon Chea concludes remarks by blaming everyone but himself

Nuon Chea blamed the strategic setbacks of the CPK regime on incapable recruits, not recognizing enemies and spies within their own ranks, American-infiltrated agents, people who did not following CPK policy (“instead, they killed and mistreated people by starving them and arbitrarily engaging them in forced labor, concealing these facts and fabricating reports, weakening the revolution and making it vulnerable to enemy invasion”), and the invading Vietnamese.

Nuon Chea returned to the topic of a fair trial. “It is my observation that some of my fundamental rights have been violated,” he said. There has been bias, failure to allow the summoning of certain much-needed witnesses, and unequal collection of the evidence, to name just three. “Your Honors have to rely on these testimonies,” he said, despite rulings and warnings that hampered his sense of fairness. “This is unequal treatment, which is why we decided not to testify anymore, because it meant nothing. You are biased and want to just make it look good in the eye of the public,” he said.

Nuon Chea concluded, saying that the evidence:

…shows I did not carry out any plan to commit the crimes. I did not provide support or encourage anyone to commit the crimes. Despite the fact I had a role as Deputy Secretary of the CPK and president of the People’s Assembly, I had no knowledge of crimes. Only at the end of the CPK period did I learn of the acts of people with intention to destroy the CPK movement and I had no authority to prevent those treacherous acts. Nor did I have any role in controlling armed forces or local authority.

If I had the authority to do the alleged, surely the 1979 court would have prosecuted and convicted me like Pol Pot and Ieng Sary. Evidence at that time was still fresh, and there was no need to wait 38 years to try me. But they knew I had no authority and did not commit any crime. Nonetheless, I would like to express my deepest remorse and responsibility to the victims, to the Cambodian people who suffered during the DK regime. The CPK policy and language were solely designed for one purpose: to liberate the country and people from colonialism, imperialism, exploitation, extreme poverty, and invasion, especially by Vietnam. We wanted an equal society.

With a few more words about the tragedy of the DK period and apologizing to a long list of groups and people wronged by the CPK, Nuon Chea said:

I still stand by my previously stated position that I am morally responsible for and pray for the lost souls. I concede that justice is circumstantial but reality stays forever. Black clouds cannot forever cover the sunlight. Likewise, bad and immoral people cannot hide reality from hope forever.

Your Honors, based on the evidence and reasons I have stated, and especially the closing statement by my defense team, I respectfully say, ‘acquit me of all charges and accordingly, release me.

Koppe takes on prosecution for one last round before the bell

With Nuon Chea done at 10:50 a.m., leaving time on the two-hour clock for his statement, and the defense team for Khieu Samphan willing to lend some time they wouldn’t be using, Victor Koppe stood for 45 minutes of closing rebuttal on behalf of his client, Nuon Chea.

As the defense did in their earlier closing statements, Koppe addressed specific issues for commentary, beginning with the “parroting” of the phrase “slave state.” This catch phrase, he said, “has been flashed like a neon sign to say it epitomized the purpose of the CPK.” But, he said, use of this slogan is not correct, and it is misleading. Whether it is based on evidence is not at issue here, said Koppe; it is outside the scope of Case 002/01. He asserted that witness statements have been “back-doored” to show how individuals were treated like slaves, and yet this information is all outside the allowable scope.

At this time, Nuon Chea requested permission from the bench to return to his holding cell, and was escorted from the trial chambers.

Koppe resumed, now on the topic of the basic principles of the right to a fair trial with reference to defense claims of uneven testing of the evidence. For example, he asked, is it right that the claim that some 2 million people died has not been properly tested? This was just one such example that resulted in a rejected motion during the trial, to his team’s dismay. Similarly, other evidence not within the scope has been treated in a similar manner, he said. Other allegations, such as how Khmer Rouge soldiers reportedly killed babies and people with glasses, are simply not admissible. “These allegations cannot be used as the poster children of Democratic Kampuchea and are not representative of the experience of people during Democratic Kampuchea. It is disingenuous and must be disregarded,” said Koppe

Koppe resumed, now on the topic of the basic principles of the right to a fair trial with reference to defense claims of uneven testing of the evidence. For example, he asked, is it right that the claim that some 2 million people died has not been properly tested? This was just one such example that resulted in a rejected motion during the trial, to his team’s dismay. Similarly, other evidence not within the scope has been treated in a similar manner, he said. Other allegations, such as how Khmer Rouge soldiers reportedly killed babies and people with glasses, are simply not admissible. “These allegations cannot be used as the poster children of Democratic Kampuchea and are not representative of the experience of people during Democratic Kampuchea. It is disingenuous and must be disregarded,” said Koppe

He then addressed allegations of the Civil Parties who, he claimed, have the impression that the defense has made a mockery of the Civil Parties. This is unwarranted, he said. The defense has never denied the suffering of the Civil Parties, and has been careful to offer them utmost sympathy. It reveals a serious misunderstanding of the role of a defense attorney, he said. “They try to say our assertions are outside the scope of DK, labeling such words as “evacuation” and “liberation” as examples of Orwellian Newspeak. “We remind that all parties have used these terms throughout the course of the trial and that the language comes straight from the closing order,” asserted Koppe. “We have remained measured in our use of language.”

Koppe spent some time examining co-prosecution submissions regarding fairness. In his opinion, the co-prosecutors are glossing over that within two days the defense answered the fair trial observations and absolved them. “Is the standard that low?” he asked before answering, “It seems the answer is yes.”

A fundamentally flawed trial?

Koppe’s greatest ire was directed at the court’s unwillingness to allow him to call as witness Heng Samrin, who, he claimed, is not only the defense’s one, only, and best, character witness, but also one of the highest-ranking contemporary Cambodian political leaders. Despite the defense team’s pleas, Koppe said, no one has responded to defense queries as to why Heng Samrin couldn’t be called. Koppe listed many possible theories, but ended by saying “Heng Samrin is the elephant in the room that the co-prosecutors and civil parties dare not speak of. Why is it they are rendered mute by this man? Either they agree his presence is of paramount importance and a fair trial cannot be had without his testimony, or they are not allowed to mention his name.” Koppe attributed his impression that the prosecution seems to be in the government’s clutches as confirmation that his client’s fair trial rights have been “irreparably harmed.”

“This trial is fundamentally political,” said Koppe. “This trial could never separate law from politics. A tribunal like this infuses law with politics. It is a viewpoint with a long pedigree in the history of international courts. Can victors of a war fairly judge its losers?” asked Koppe. “Nuon Chea’s view that he cannot be judged deserves serious reflection.”

The prosecution mentioned that it had devoted 40 pages of its brief to historical analysis, but Koppe asked, “which history?” Why is the American bombing hardly mentioned? Does anyone doubt the intent of CPK policies changes radically in light of the ruthlessness of the enemy it was actually fighting? Do co-prosecutors dare accuse the people currently responsible for running this country? The answer is, of course, no, said Koppe.

Koppe proceeded to address Nuon Chea’s decision not to subject himself to cross-examination. Nuon Chea, he explained, felt he’d had enough of his rights being violated. He cited, as one example of these perceived violations, the fact that the defense team was not allowed to challenge the testimony of Mr. Stephen Heder.

Mr. Koppe also re-addressed the issues of “rogue” leaders being at the center of the second forced transfer. For the record, Mr. Koppe said, “We have never said it was rogue. This, portrayal is their formulation and it is nonsense.” The zone leaders had primary control and authority – but they were not “rogue,” he asserted.

Six final key points in the discussion about Tuol Po Chrey

Mr. Koppe turned for a last time to the topic of Tuol Po Chrey, discussing the episode at length. His main points, briefly summarized here, were:

- The prosecution never challenges or contests evidence or calls it unreliable;

- Two photographs held up as legitimate evidence were unreliable, according to Koppe

- The evidence of a pattern of killings failed to show a centralized policy and is irrelevant;

- The prosecution’s assertion that defense failed to address the core claim of Tuol Po Chrey was refuted by Mr. Koppe at length. Ambiguity is at the heart of the issue, according to him, and there is simply no clear evidence that people were systematically executed.

- The vague class warfare theory that Duch claims to have read in Revolutionary Flag wasn’t intended and never promoted execution. “This alone,” asserted Koppe, “leads me to claim clearance of the charges against my client regarding Toul Po Chrey.”

- It was the end of a bloody civil war. Some revenge killings under these circumstances were unavoidable.

For his final comment, Mr. Koppe revisited the co-prosecution’s analysis of Ros Nhim in the CPK, and leadership roles generally. “The critical point is that Ros Nhim was not a mere zone leader. He was a member of the Standing Committee, an equal participant in the committee’s practice of democratic centralism. Nuon Chea met with Ros Nhim quarterly in the Northwest zone. “So what? What does it say?” asked Koppe. Ieng Sary said that each zone was independent (known for a free-wheeling “do as you please, kill as you please” attitude). The hard reality of Ros Nhim, said Koppe, is he was ultimately purged. If Nuon Chea could so easily control Ros Nhim, why did they deem it necessary to use military force against him?

Vercken speaks for the defense of Khieu Samphan

With that the chamber broke for lunch. At 1:30 p.m., Mr. Vercken took the stand to give the final rebuttal for the Khieu Samphan defense team. His comments were succinct and brief. “We did not hear anything yesterday that would warrant a fundamentally different statement from our side, or because they weren’t relevant or were in our final submission we have already responded or done so through our pleadings,” he said.

With that the chamber broke for lunch. At 1:30 p.m., Mr. Vercken took the stand to give the final rebuttal for the Khieu Samphan defense team. His comments were succinct and brief. “We did not hear anything yesterday that would warrant a fundamentally different statement from our side, or because they weren’t relevant or were in our final submission we have already responded or done so through our pleadings,” he said.

He gave brief attention to one argument cited but, because he deemed it irrelevant, he went into no further detail. On a different matter regarding expansion of the scope of the trial, he said, “We do not wish to dwell on these things because they have no bearing.”

There was brief attention paid to an issue of viewing the historical context for the situation, but this, too, was finished with quickly.

Regarding the second population movement, Mr. Vercken reiterated the fact that Khieu Samphan was out of the country and that there has been no evidence that Khieu Samphan took part in the implementation of that movement (Aug 1975-1976),

Mr. Vercken ended by taking one more look at the many words that have been said about JCE responsibility. He pointed out how the prosecution had asked that a “systematic form” of joint criminal enterprise theory be applied. However, said Mr. Vercken, if the case law of international tribunals has conceived a variation on the basic form of JCE (a variation in which the necessary threshold for proof of intent is lower), then it is because there were reasons for that having to do with a specific context—not to award some sort of gift to prosecution teams throughout the world. The situations in which the variation has been applied, he said, have to do specifically with the operation of extermination camps in confined, limited areas. “Here today you’re being asked to say all of Cambodia was a concentration camp and therefore that this kind of [systematic] JCE applies,” said Vercken. “This is beyond the bounds of reason and not the context that the case law was established for, it does not correspond to the spirit of the law.”

A final point by Mr. Vercken was that the prosecution team is going further in many of their arguments, they’re asking for the expanded form of JCE. Vercken reminded the bench that it was a form excluded by the judges before this trial even opened. The prosecution wants it to be possible for the accused to be secured through the fact that it was foreseeable that crimes could be committed, he said, but that such a standard cannot be applied is something “you, Your Honors, decided before the trial began,”

Khieu Samphan finally has his say

Mr. Vercken concluded at 1:45 p.m., and turned the attention of the court to his client, Khieu Samphan, who read the following statement:

Over the last couple of days, I have listened attentively and heard it clear and loud, the interventions by all parties, particularly the interventions of those who have criticized me for not speaking enough in my current case. Ironically at the same time those same individuals have maneuvered and manipulated my little speeches as their basis for allegations against me. Therefore, although I try to explain in good faith, refuting the various charges brought against me, you will continue to criticize me and if I choose to remain silent, you still accuse me.

I would like to make it clear that I never wanted or decided to evacuate the people and neither did I plan or decide the massacre of innocent people. My political conviction and conscience at that time, given the reality on the ground, whatever I did was to protect the weak, was to hold the respect for their fundamental rights. And to build a Cambodia that was strong, independent and peaceful. Indeed, widespread social injustice made me disheartened and discontented with the regime, but I was not so discontented that I sought tit for tat or revenge. My underlying intention and wisdom was to bring about independence, peace, and prosperity to Cambodia. I only wanted people to live with dignity.

However, when I heard the charges brought against me and how these charges were constructed here, and in addition, when I witnessed that those who will sit to the side on my case have refused to take into consideration the real situation on the ground at that time, but instead form a preconception that I was a monster, I have lost desire to say anything further.

Indeed, during the Lon Nol era, following the coup d’état, I wanted the Khmer Rouge and its allies to win the war against Lon Nol and I did rally them at the time. Indeed, following the resignation of Sihanouk from head of state in 1976, I had the full confidence that we would help each other rebuild the country to be a prosperous one. Everyone here today, you seem to have believed that I was guilty, because all of you believe that I should have foreseen what would happen following the 17April 1975 and that I should have recused or deserted the Khmer Rouge.

The fact that I remained with them amounts to the allegation that I was a culprit and deserve conviction even though I have explained the truth to the best of my knowledge. To them I should have remained indifferent and let the Lon Nol regime issue the course of action. To them, I should not have taken any action to respond to Lon Nol. And to them, following the victory over war against Lon Nol and America, I must have known that my political conviction and wisdom would not be implemented, but instead, it would be reversed completely under the absolute control of the power of the Khmer Rouge, who enforced their various measures strictly.

I would like to reiterate that I did not witness the things that could have happened following the victory and neither did I have any power to intervene or sanction or rectify anything. Some even said I was a coward. The reality was that I did not have any power, and I did not care about it either. This could have been probably my mistake because subsequently I remained close with those powerful individuals, but I was powerless. All of you believe I had effective power at that time, which is why today I was brought and put on trial.

Today, it is easy to say that I should have known everything I should have understood everything and thus I could have intervened or rectified the situation at the time. Do you think that I did not try my best to understand the situation? Do you really think that that was what I wanted to happen to my people? When I was a youth, I tried my best in order to change a regime full of injustices, and later I had to escape for my life from persecution. I would have been killed if I had not fled into the jungle. Subsequently, upon learning that there was a group of people better equipped to fulfill this noble task in the interest of the Cambodian people and nation, I wanted this group to succeed in their endeavors. I then provided them with my little support. At the time I had the faith and confidence in their revolutionary plan. I was convinced it would bring about betterment for Cambodia and that Cambodia would last. For our poor unfortunate nation had suffered from a destructive war. Our country was destroyed so badly that widespread famine was looming. Completely contrary to what has been raised before this chamber, never had I participated in the plan that led to the suffering of the people. I was never at any time a part of this plan. Never. As I have tried to explain to the civil parties who testified and shared their suffering before this chamber, I never sought that such a thing would happen to my people.

This is the one thing I want to reiterate today, because it is the truth. But nobody wants to listen to me. Given his indifference regardless of my attempt to explain the truth and given the state of conditions of the current proceedings before this chamber, I have a strong feeling that no matter how hard I try to explain they will only turn deaf ears to me. They will still not pay attention to what I have to say. Instead I feel that the more I speak, the more vengeance they have against me. Therefore, I think that I don’t have to be silly trying to explain to those who never want to listen to me. I myself have a deep regret that I had all the faith and confidence in this tribunal from its early days that it would secure me an opportunity to explain. But unfortunately, to date it is clear that everyone wants only one thing from me: my admission of guilt according to charges brought against me, the charges concerning the acts that I had never ever committed at all. Because I did not know what happened subsequently following the victory, I had no reason to admit the guilt despite mounting pressure on me. I am of the view that if I remain silent, I can maintain my honor and dignity and I will leave it entirely to you, wise judges, to adjudicate on my case. My defense counsels and their dedicated team have defended me rigorously and with conviction, for which I am most grateful, regardless of the result. I firmly hope that whatever it is, you wise judges will find justice. Thank you.

Khieu Samphan (right) Escorts Burmese President Ne Win in November 1977

Source: Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives

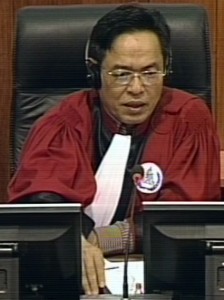

Nonn announces the end of the trial, and what to expect next

Thus it was that at 2:10 p.m., chamber president Nonn said in the wake of completion of evidentiary hearings and closing statements, “The proceedings to hear the closing statements by all parties in Case 002/01 as part of case 002 has come to an end.” The president of the trial chamber summarized Case 002/01 as follows:

- This concludes the substantive hearing on case 002 on the evidence 001 which forms the first phase of case 002 in which the two accused are charged with Crimes Against Humanity;

- Since the start of the evidentiary hearing on Nov. 21, 2011 and concluded July 23, 2013, the trial chamber has held 212 days of hearings along with closing statements which commenced October 16, 2013 through today, October 31, 2013 taking another 10 days. Thus, in whole, the substantive hearing took 222 days in total;

- The trial chamber has heard 92 individuals, among whom there are 3 expert witnesses, 57 witnesses and 32 civil parties, plus two treating doctors and two medical experts who also testified on medical conditions of the accused;

- The chamber has been seized of more than 290 written applications and rendered more than 250 written and oral decisions, and;

- More than 4,000 documents consisting of 166,500 pages in three languages have been admitted as evidence in case 002/01 by the chamber.

Mr. Nonn continued to demonstrate the gigantic nature of the case by explaining that the parties to the proceedings have made requests for the admission as evidence numerous documents and materials. He offered a very long list of the sorts of documents that have been accumulated. At this juncture, the substantive hearing in case 002/01 is considered complete

Mr. Nonn continued to demonstrate the gigantic nature of the case by explaining that the parties to the proceedings have made requests for the admission as evidence numerous documents and materials. He offered a very long list of the sorts of documents that have been accumulated. At this juncture, the substantive hearing in case 002/01 is considered complete

Before he announced the official conclusion of the closing statements, Mr. Nonn said the trial chamber wished to thank the parties to the proceedings, everyone. He named those who gave testimony, the ECCC Office of Administration (and units under its supervision, especially the interpretation and translation unit and the booth interpreters); all support personnel, the Royal Government of Cambodia and its institutions, even the firefighter and medical sections. Not least, he thanked personnel from organizations and centers for physical and emotional support, such as the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) since the outset through to “this fruitful end.”

Mr., Nonn then proclaimed that, “The trial chamber wishes now to pronounce conclusion of the proceedings to 002/01, and inform parties that after this the trial chamber will commence deliberation and prepare its judgment regarding case 002/01.” The trial chamber has not been able to set a date due to the fact that “the case is voluminous and complex and needs to be prepared into three languages. We will notify the date for pronouncement of the judgment in due course,” said Mr. Nonn.

In reference to the proceedings regarding the severance, Mr. Nonn said that the chamber will hold a trial management meeting from on Dec. 11-13, 2013 to discuss the preparation of future trials in case 002.

With that, the trial chamber for Case 002/01 adjourned at 2:20 p.m.

A press conference in the ECCC gallery ensued, at which all the attorneys for the prosecution, defense, and civil parties sat at the table one at a time for statements followed by Q&A for the large gathering of national and international press. A brief report on this session is forthcoming from Cambodia Tribunal Monitor.